When Frances Trollope wrote about New York in her Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), she praised the city’s upper class as a “small patrician band”—“the Medici of the Republic”—whose refined manners and genteel way of life met the highest European standards. The Medici were flattered, not least of all because Mrs. Trollope had endorsed their belief that they were better than everyone else, yet had remained true to the nation’s republican heritage. What she didn’t relay to her readers were the conflicting denominational sensibilities and ethnic allegiances that divided the snug little patriciate into at times competing factions.

One camp consisted of the recent arrivals from New England, who were inclined toward evangelical reform and found the Presbyterian Church an acceptable substitute for the Congregationalism of their native region. The other comprised old-stock Anglo-Dutch and Huguenot bluebloods—dubbed Knickerbockers after the character in Irving’s history—who tended to think of religious zeal as fanaticism and felt most comfortable in the Episcopal fold. As one of them would tartly put it: “Our graceless Knickerbockers danced around the May-Pole in the Bowery, while the Puritan Anglo Saxons burned witches at Salem.”

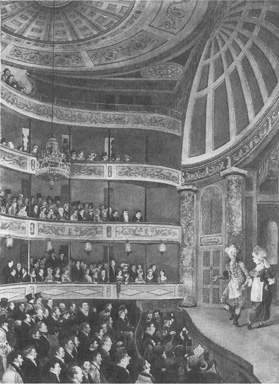

A characteristic point of conflict between Yankees and Knickerbockers was their attitude to the theater. Knickerbockers loved the stage, and a performance at the Park Theater—which Mrs. Trollope identified as the only house in town “licensed by fashion”—was certain to bring out an abundance of Beekmans, De Lanceys, Kents, LeRoys, Bayards, Livingstons, and Van Renssalaers. More than eighty can be identified in the painting that John Searle made of the Park’s audience one night in 1822. Pious Yankees, however, are conspicuously absent from Searle’s canvas, having no doubt heeded the admonition of the Rev. Gardiner Spring, pastor of the Brick Presbyterian Church (just up the street from the Park), that playgoing encouraged licentious habits, especially among the young. Spring’s views were shared by Arthur Tappan, a successful silk merchant and evangelical who felt about vice (according to his younger brother, Lewis) as he would about a toad in his pocket. Although his annual income reached as high as thirty thousand dollars during the 1820s, Tappan pointedly poured his money into charity rather than preening display or self-indulgence. His usual lunch consisted of a cracker and a tumbler of cold water. He held his clerks to equally strict standards, insisting that they attend divine service regularly (twice on Sundays), get home by ten each night, and never, ever, visit a theater or consort with actresses.

Interior of the new Park Theatre, 1822, watercolor by John Searle. Fire destroyed the original Park Theatre in 1820, but its replacement, which opened the following year, was no less fashionable. Searle’s portraits of the audience comprise a visual directory of the Knickerbocker elite. William Bayard, the wealthy merchant who commissioned the work, is standing in the first tier, behind the lady who has draped her shawl over the rail. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Yankees likewise vilified horse racing, another Knickerbocker enthusiasm that enjoyed wide popular support. Although the state banned the sport in 1802 as a vestige of aristocratic dissipation, Long Island gentry got the ban reversed, though only for Queens County, on the ground that it impeded the improvement of breeds. The Union Course, out on the plains of Jamaica, soon became one of the premier tracks in the country, famous for its huge purses and the multitudes who came out from the city to watch, gamble, and carouse. In May 1823 the track tapped sectional rivalries by hosting a match race between the fastest mount in the North, Eclipse, and a southern challenger, Henry. Some twenty thousand spectators showed up, a million dollars in wagers allegedly changed hands, and the Evening Post brought out a special edition to announce that Eclipse had carried the day. The victory did nothing to dispel Yankee convictions that racing was wicked, and when the Union Course was later bought and refurbished by Cadwallader Colden, the eminent Knickerbocker, they knew who to blame for encouraging it.

Waltzing too was in disfavor. Exclusive, meticulously arranged dancing “assemblies” were no less a feature of upper-class socializing than they had been before the Revolution, but the younger and more adventuresome set now regarded the cotillion or quadrille (ancestor of the modern square dance) as unbearably old-fashioned. They preferred the “valse,” which came to New York via Paris in the 1820s and was thought quite daring because dancers whirled around the ballroom in couples. Yankees and Presbyterian ministers denounced it as the devil’s work. Knickerbockers and Episcopalians seemed less concerned, even tolerant.

Nothing raised Yankee hackles like Sabbath-breaking, however. True, the bustle and frivolity of Sundays in New York had been a sore subject among devout residents for nearly two hundred years now. But newcomers from Connecticut and Massachusetts had still-warm memories of communities where families observed the Sabbath by abstaining from all forms of recreation, dining on cold collations of Saturday-baked meats, and attending multiple church services. They could see, too, that the city’s recent growth had spawned alluring new opportunities for diversion on Sunday—pleasure gardens serving punch and wine, even to unescorted single women, and steam-powered pleasure boats providing musical excursions around Manhattan (“a refinement, a luxury of pleasure unknown to the old world,” their proponents preened)—all apparently aided and abetted, and some owned as well, by easygoing Knickerbockers.

In 1821 the Rev. Spring and the Sabbatarians launched a boycott of newspapers that advertised Sunday excursions and won the support of Mayor Stephen Allen. Then they got up a petition asking the city to enforce biblical injunctions to keep the Sabbath holy by closing down pleasure gardens, markets, livery stables, newspapers, and the post office. In time, they meant to sweep the Hudson free of sloops and steamboats “filled with profaners of the Lord’s day.”

The reaction was swift and overwhelmingly negative. Most newspapers defended steamboat excursions as innocent amusement. The Evening Post justified keeping markets open on Sunday as necessary for the poor, who went unpaid until late Saturday and couldn’t afford iceboxes to keep fish, meat, and milk fresh during hot weather. Thousands of residents signed a rival petition denouncing clerical interference in public affairs as “highly improper,” while handbills and placards went up around town attacking Spring and his ministerial allies as bigots. When Spring’s forces announced a public rally at City Hall, the Mercantile Advertiser urged anti-Sabbatarians to show up en masse. They did so, seized control of the meeting, and adopted a resolution stating that the citizens of New York wanted the clergy to mind their own business. (“The excited multitude looked daggers at us,” Spring recalled.) The Sabbatarians retreated, and the Knickerbockers congratulated themselves on their stand for tolerance and bonhomie.

What the Knickerbockers lacked was an organization comparable to the New England Society, whose annual dinner to commemorate the landing of the Pilgrims generated endless bragging about Yankee virtues and Yankee achievements. More than a few Knickerbockers took up Freemasonry, which combined fraternalism with a commitment to religious toleration and rationalism. By 1827 there were forty-five Masonic Lodges in New York, each of which met twice monthly, either at old St. John’s Hall or at the imposing new Gothic-style Masonic Hall on the east side of Broadway, between Duane and Pearl, nearly opposite the New York Hospital.

Eventually, in 1835—after two years of prodding by Washington Irving—the Knickerbocracy gave birth to a club all its own, the St. Nicholas Society. One of its declared purposes was to gather information on the history of the city, a subject that seemed to particularly interest old-guard New Yorkers. What mattered to the wealthy merchant and former mayor Philip Hone, though, was the promise “to promote social intercourse among native citizens”—meaning men of “respectable standing in society” whose families had resided in New York for at least fifty years. A “regular Knickerbocker Society,” Hone noted in his diary, would serve “as a sort of setoff against St. Patrick’s, St. George’s, and more particularly the New England [societies].” Peter Gerard Stuyvesant, great-great-grandson of Petrus, was elected first president, and three hundred men with names conspicuous in the city’s history—De Peysters and Duers, LeRoys and Roosevelts, Lows and Fishes—signed up at once. A second St. Nicholas Society soon sprang up across the East River, rallying Sandses, Leffertses, Bergens, Suydams, Strykers, and Boerums to the defense of Brooklyn against insolent and upstart Yankees.

But not every question that roiled upper-class New York followed this pattern: partisan political alignments cut across the Yankee-Knickerbocker boundary, as did controversies over such economic issues as the tariff. More important still, none of these clashes of style, principle, or interest provoked permanent rifts in New York’s upper registers. Numerous circumstances allowed old-timers to fashion a detente with newcomers and construct a common class identity, rather as the wealthy Dutch and English had worked out a rapprochement a century earlier.

The city’s galloping prosperity, for one thing, enabled Yankees and Knickerbockers alike to make so much money so fast that their differences paled alongside their combined riches. In the buoyant economy, profits rose to the top like cream: by 1828 the top 4 percent of taxpayers possessed roughly half the city’s assessed wealth—more than the top 10 percent had owned a half century earlier. Then, too, although New Englanders now ruled the wholesale and retail mercantile trade—LeRoy and Bayard, the last great Knickerbocker firm, folded in 1826—their rivals hadn’t died out. Rather, they moved nimbly into banking, lawyering, transportation, shipbuilding, insurance, the stock market, and, above all, real estate. As ever, money begat money, and if the son of a rich man didn’t stay in the family business, the family could get him off to a fast start in some other line of work. In fact, nine out of ten affluent New Yorkers in the 1820s and 1830s were wealthy before they embarked on their careers.

Besides money there was style, and nowhere were the commonalities among well-to-do gentlemen and ladies in New York more plainly visible than in their evolving sense of fashion. Beginning in the 1790s the peacock regalia of eighteenth-century males—cocked hats, greatcoats with turned-up cuffs and gilt buttons, embroidered waistcoats, snowy cravats, lace ruffles, buckskin knee breeches, silk stockings, and shoes with silver buckles—had fallen rapidly out of favor. Well-dressed men now favored trousers or close-fitting pantaloons (“pants”), along with double-breasted frock coats, preferably in a circumspect black (a color once reserved for mourners and the clergy). They wore their own hair, unpowdered, closed their shirts at the collar with the simple white neckcloths known as “stocks,” and covered their heads with high-crowned top hats. Dandies affected tighter pants, flashy vests, bright green gloves, and an eyeglass for inspecting curiosities—and were scorned by etiquette advisers as effeminate. The trend was unmistakable. Aristocratic plumage had succumbed to republican simplicity and bourgeois restraint: a gentleman conveyed social superiority through consummate tailoring and impeccable grooming, not color and ornamentation.

Female fashion followed a similar trajectory. Heavy brocaded skirts with whaleboned bodices and hooped petticoats, all the rage in the mid-eighteenth century, yielded during the first two decades of the nineteenth to lighter, neoclassical designs inspired by the French empire and then the Greek struggle for independence. Their objective was a free and natural silhouette: high-waisted dresses of sheer white muslin, featuring low rounded necklines and a bandeau (precursor of the bra) that emphasized the bosom, typically worn with a shawl and with the hair piled up in reckless masses of curls. After 1830, however, the prevailing taste retreated to more constrained, less revealing styles. Waistlines became lower and narrower, necklines rose, and the natural contours of the body were concealed with boned corsets, voluminous skirts, layers of petticoats, padded bustles, and enormous leg-of-mutton sleeves. Modesty now required that hair be pulled back, drawn into a demure knot, and covered with a frilly bonnet.

Shared tastes in costume were accompanied by a similar determination to settle in neighborhoods where the better sort of people, Yankees and Knickerbockers alike, could insulate themselves from the seamier elements of urban life. In 1820 the choicest addresses in town still lay on the lower west side of Manhattan, along Broadway (from Bowling Green up to Chambers), Greenwich Street (which paralleled the Hudson), and the quiet, tree-shaded blocks in between. From here gentlemen could easily walk to their places of business on Wall Street or Hanover Square, and their families could walk to one of the many houses of worship nearby—the great Episcopal bastions of Trinity and St. Paul’s on Broadway, say, or perhaps the First Presbyterian Church on Wall, Brick Presbyterian on Beekman Street, St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church on Barclay Street, John Street Methodist, the Dutch Reform triplets (Old South on Exchange Place, Middle on Liberty Street, and Old North on William Street), South Baptist on Nassau Street, or Shearith Israel on Mill Street, still the only synagogue for New York’s four hundred Jews. Also within easy walking distance was the Battery. Spruced up in the early 1820s with lawns, shade trees, and an ornamental iron railing, it remained the city’s premier park and promenade. Its appeal was further enhanced in 1824, when the city acquired Castle Clinton from the federal government and leased it out as a “place of resort,” tethered to the Battery by a wooden bridge ninety paces long and illuminated by gas lamps. Two years later, refurbished as a theater, it became Castle Garden. The high price of tickets to the Garden’s varied performances guaranteed respectable audiences.

Throughout the 1820s some of New York’s most prominent Yankees and Knickerbockers nestled around the Battery and its adjacent blocks, so many that Bowling Green was irreverently dubbed Nobs’ Row. Other affluent families settled along Broadway itself. In 1828 over one hundred of the city’s five hundred richest men lived there. Among them was Philip Hone, who had retired in 1821 at the age of forty from the auctioneer business with money enough to purchase a house directly across from City Hall (making for an effortless commute during his 1825 term as mayor). Even the censorious Mrs. Trollope loved Broadway, that “noble street.” Though lacking “the gorgeous fronted palaces of Regent-street,” it was nevertheless “magnificent in its extent.” Its “neat awnings, excellent trottoir [sidewalk], and well-dressed pedestrians” were so appealing that she might have moved there herself, she confessed, “were it not so very far from all the old-world things which cling about the heart of an European.” Roosevelts, Astors, Grinnells, and Aspinwalls were nonetheless quite content to occupy the elegant three-story row houses that fronted blocks running west from the strip of Broadway adjacent to City Hall Park down to the Hudson shore.

Broadway between Park Place and Barclay Street, 1831 (now the site of the Woolworth Building), directly opposite City Hall. The private house on the right was occupied by Philip Hone, who had settled there a decade earlier, when Broadway was still lined with fashionable private residences. Only a half-dozen years later, surging commercial growth—marked by the expansion of the adjacent American Hotel and construction of Astor House one block to the south—would transform the neighborhood. (© Museum of the City of New York)

Yet for all its charms, lower Broadway was losing its exclusivity in these years. Clerks, shopkeepers, and laborers trod its excellent trottoir on their way to and from work. Pigs wandered over from all-too-near poor neighborhoods. Commerce and the business district expanded rapidly northward. Old private homes were converted to boardinghouses for young merchants, clerks, and out-of-towners. The growing number of shops, hotels, restaurants, and theaters produced, said the Mirror, a “confused assemblage,” mixing people of high and low degree.

More and more wealthy residents thus began a long, reluctant march uptown in search of more hospitable enclaves. One destination was Hudson Square, also known as St. John’s Park, which had been opened by Trinity twenty years earlier but had failed to attract residents. In 1827, however, the vestry decided to sell rather than lease lots and deeded the square itself to purchasers. They poured in by the score, threw up a tall iron fence around the square, and landscaped it with catalpas, cottonwoods, horse chestnuts, silver birches, flowerbeds, and gravel paths. The neighborhood for blocks around soon bristled with Hamiltons, Schuylers, Delafields, Tappans, and other prominent families whose elegant brick town houses afforded refuge from the sweaty commotion of the city below. Nothing else in New York so closely approximated the beauty and exclusiveness of the great squares of London’s West End. It was, according to one contemporary report, “the fairest interior portion of this city.”

Battery Park, 1830. A field of fashionable bonnets and top hats, well-behaved children, carefully maintained grounds—everything in this scene of the Battery conveys its continuing prominence as a hub of respectable New York. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

A second destination for rich urban refugees lay even further uptown, where Broadway sliced through Bleecker, Bond, Great Jones, and East 4th streets, just below John Jacob Astor’s Vauxhall Gardens. Building sites on this northern frontier of the city were ample enough for patrician-sized dwellings with commodious yards, gardens, and stables; one guidebook announced that they “may vie, for beauty and taste, with European palaces.” Arguably the most desirable addresses lay along Bond Street, where Jonas Minturn built the first house in 1820. Its white marble facade set the pattern for the expensive three-and four-story residences that stretched the length of the street, from Broadway to the Bowery, by the mid-thirties.

Bond Street’s principal rival was the wide nine-block sweep of Bleecker Street from the Bowery to Sixth Avenue, and in 1828 the portion of Bleecker between Mercer and Greene streets became the site of New York’s first experiment with terraces—grand residential blockfronts of the kind seen in the most fashionable London neighborhoods. Christened LeRoy Place in honor of the Knickerbocker merchant Jacob LeRoy, its Federal-style row houses sold for a hefty twelve thousand dollars. But LeRoy Place was promptly eclipsed by the resplendent La Grange Terrace, completed in 1833 on the west side of Lafayette Place (itself opened by the canny Astor only half a dozen years earlier). Also known as Colonnade Row, for its magisterial procession of two-story Corinthian columns, La Grange Terrace consisted of nine residences that sold for as much as thirty thousand dollars apiece. They were reportedly “the most imposing and magnificent in the city.”

St. John’s Chapel and Hudson Square, from the New York Mirror, April II, 1829. This genteel bastion—bounded by Hudson, Varick, Ericsson, and Laight streets— fell abruptly out of fashion after 1850 and was sold to Commodore Vanderbilt, who built a four-acre freight depot on the site in 1866. It is now overrun by automobiles exiting the Holland Tunnel, and the memory of McComb’s chapel is recalled only by St. John’s Lane, a block east. (© Museum of the City of New York)

The exodus of well-to-do New Yorkers out of lower Manhattan took a toll on many downtown churches—even Gardiner Spring moved up to Bond Street—and their denominations, Yankee and Knickerbocker alike, moved quickly to establish new congregations uptown. A Dutch Reformed church opened on the corner of Houston and Greene streets in 1825; the Bleecker Street Presbyterian Church, just east of Broadway, in 1826. The Episcopalians consecrated the stately, Gothic-style St. Thomas’s at Houston and Broadway in 1826, followed ten years later by the sumptuous St. Bartholomew’s, at Lafayette and Great Jones.

Even these houses of worship were inaccessible to affluent New Yorkers who fled still farther away from the city, all the way up Third Avenue until it dwindled to a country lane in the higher latitudes of northern Manhattan. In May 1831 their mansions caught the eye of Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave Beaumont, two Frenchmen who had come to explore America’s jails and America’s democracy. As their steamboat from Providence cruised past the East River shore, the two marveled at the “unbelievable multitude of country houses, big as boxes of candy,” whose grassy lawns and orchards sloped down to the water. More and more of these bucolic summer retreats had become full-time residences, from the Stuyvesant estate just below 14th Street (where boys still filched pears from trees planted by old Petrus), and the thirty-acre Phelps estate at Kip’s Bay between 29th and 31st streets, all the way up to Archibald Gracie’s lovely Federal-style mansion between 86th and 90th streets. By the 1820s these regions had so many permanent inhabitants that St. James’s Church—a wooden Trinity outpost at 69th and Lexington—began year-round worship.

The isolation that wealthy New Yorkers sought in their uptown encampments made travel into the city something of an ordeal. Bond Street merchants and bankers occasionally walked the two miles down to Wall or Pearl. Yet daily commuting required swifter, less tiresome transportation, and absent the use of a private carriage or cabriolet (a two-wheeled vehicle drawn by a single horse), the alternatives proved sadly limited. One option was to suffer through an uncomfortable ride atop one of the stagecoaches that ran downtown from the corner of Broadway and Houston Street. Another was to hail one of the licensed hackney carriages that congregated at stands by the Park, Bowling Green, Trinity Church, and Hanover Square. Hacks weren’t plentiful, though (only 180 served the entire city in 1828); they weren’t cheap; and as Mrs. Trollope discovered, “it is necessary to be on the qui vive in making your bargain with the driver; if you do not, he has the power of charging immoderately.” At the least, a Bond Street gentleman might spend two hundred dollars a year getting to and from work.

The demand for better transportation between the downtown business district and elite uptown neighborhoods inspired New York coachmakers to introduce the omnibus, an innovation that had recently appeared in London and Paris. Seating a dozen or more passengers, and drawn by huffing teams of two or four horses, the first of these boatlike vehicles began rumbling along Broadway from Bowling Green to Bond Street in 1829. The idea caught on quickly. Within a decade there were over a hundred omnibuses in operation along the city’s principal thoroughfares, gaily painted and sporting heroic names like the General Washington, the Benjamin Franklin, and the Thomas Jefferson. Philip Hone, who himself had moved uptown to the corner of Broadway and Great Jones Street, reveled in the ease with which they allowed him to get downtown. “I can always get an omnibus in a minute or two by going out of the door and holding up my finger,” he said.

Although omnibus means “for all” in Latin, this was class, not mass, transit. It cost twelve and a half cents for a one-way trip down to Wall Street, which was cheaper than the hacks but well beyond the reach of common laborers earning a dollar a day. Even well-to-do passengers found things to complain about, to be sure: grime, unpadded benches, poor ventilation in the summer, no heat in the winter, an often maddeningly slow pace through downtown traffic, and frequent overcrowding. For people living on their estates north of town, omnibuses were no use at all.

Nor were the omnibuses generally able to get gentlemen back uptown in time for dinner. Until 1830 or so, dinner had been the main meal of the day for upper-class New Yorkers, served enfamille at two or three in the afternoon, followed by a light and informal supper in the early evening. As the distance between home and office increased, however, men of affairs found it more convenient to make a quick midday snack of oysters or clams bought from street vendors (“Here’s your fine clams, as white as snow, on Rockaway these clams do grow”) or to have “lunch” together at business-district restaurants like Dyde’s on Park Row or the Porter House on John Street. Back home, meanwhile, wives and small children made do on cold meat, soup, bread, cheese, and other breakfast leftovers. “Dinner” now waited until Father returned in the early evening, while supper was pushed back to nine or ten o’clock or abandoned altogether.

The rescheduling of dinner was accompanied by changes in the consumption and presentation of food that would make the meal as much an emblem of gentility as restraint in fashion or a choice address. Guests no longer arrived to find the table already laden with dishes, which the genial host would dispense, amid much communal passing of plates. Instead, servants (who no longer ate with the family) distributed dishes in a carefully specified order: first soup and fish, then meat and vegetables, finally pies and puddings, which Americans had begun to call “dessert.” The new manners did encounter some opposition—“This French influence must be resisted,” Philip Hone declared—but the more ceremonial and “refined” mode eventually prevailed.

Food preparation too changed in upper-class households. Breads, hoecakes, and johnny cakes, once made in an open hearth, were baked in new cast-iron cookstoves, using the new “refined” white flour that came down the Erie Canal from the new Rochester mills. Meat wasn’t boiled in a pot or spitted over a fire, as in the past, but oven-roasted and served with fancy sauces. The mistress crafted ornate pastries and compotes from recipes gleaned out of increasingly complex domestic manuals like Lydia Maria Child’s Frugal Housewife (1829). Costly imported porcelain and silverware, once reserved for guests or special occasions, were now considered de rigueur for everyday use.

Changes in the dinner ritual were further evidence that for upper-class New York households “work” and “home” increasingly occupied distinct social spaces, one ruled by men, the other by women. By the 1820s the downtown commercial district was well on its way to becoming a separate male preserve—virtually empty of respectable families, and scrupulously avoided by respectable women except for shopping expeditions to lower Broadway or visits to the Ladies’ Dining Room of the City Hotel. John Pintard, then living over the offices of the Mutual Insurance Company on Wall Street, realized that his wife and daughter were “nearly prisoners during the hours of business in Wall Street.” In 1832 a popular guide to the city advised “distant readers” that no women appeared in its pictures of the area because women rarely went there. So, too, the Mirror reported a few years later that “the sight of a female in that isolated quarter is so extraordinary, that, the moment a petticoat appears, the groups of brokers, intent on calculating the value of stocks, break suddenly off, and gaze at the phenomenon.”

This was as it should be. Decent women didn’t belong in the heartless, bare-knuckled free-for-all that raged downtown, for according to the conventional wisdom, proclaimed over and over again in the pulpit and in the press, nature designed the female of the species to be pacific, nurturing, and cooperative. Her proper sphere was the Home, and her duty— essentially a refinement of the ideal of republican motherhood—was to make the Home a haven for her weary husband and a nest where she imbued her children with Christian love and humility. A genteel household was thus the very antithesis of the marketplace yet indispensable to it, a place where men returned at the end of the day to be refreshed for battle the next and where the young acquired the moral armor they would need as adults.

Wealthy New Yorkers didn’t invent this new cult of domesticity, which was a characteristic of emerging bourgeois culture throughout the Atlantic world. They did, however, give it Christmas—a holiday that became synonymous with genteel family life and a quintessential expression of its central values.

For 150-odd years, probably since the English conquest, the favorite winter holiday of the city’s propertied classes was New Year’s Day (as distinct from the night before, which was an occasion for revelry and mischief among common folk). Families exchanged small gifts, and gentlemen went around the town to call on friends and relations, nibbling cookies and drinking raspberry brandy served by the women of the house. Sadly, according to John Pintard, the city’s physical expansion after 1800 rendered this “joyous older fashion” so impractical that it was rapidly dying out.

As an alternative Pintard proposed St. Nicholas Day, December 6, as a family-oriented winter holiday for polite society. In Knickerbocker’s History, Pintard’s good friend Washington Irving had identified Nicholas as the patron saint of New Amsterdam, describing him as a jolly old Dutchman, nicknamed Sancte Claus, who parked his wagon on rooftops and slid down chimneys with gifts for sleeping children on his feast day. It was Salmagundi-style fun, of course: although seventeenth-century Netherlanders had celebrated St. Nicholas Day, the earliest evidence of anyone doing so on Manhattan dates from 1773, when a group of “descendents of the ancient Dutch families” celebrated the sixth of December “with great joy and festivity.” Certainly nothing remotely like the Sancte Claus portrayed by Irving had ever been known on either side of the Atlantic.

Mere details were no obstacle to Pintard. On December 6, 1810—one year to the day after the publication of Irving’s History— he launched his revival of St. Nicholas Day with a grand banquet at City Hall for members of the New-York Historical Society. Their first toast was to “Sancte Claus, goed heylig man!” and Pintard distributed a specially engraved picture that showed Nicholas with two children (one good, one bad) and two stockings hung by a hearth (one full, one empty)—the point being that December 6 was a kind of Judgment Day for the young, with the saint distributing rewards and punishments as required. St. Nicholas Day never quite won the support Pintard wanted, and he eventually ran out of enthusiasm for the project. Sancte Claus, on the other hand, took off like a rocket. Only a few years later, in a book for juveniles entitled False Stories Corrected, he was already under attack as “Old Santaclaw, of whom so often little children hear such foolish stories.”

Other New Yorkers of Pintard’s ilk were meanwhile taking a second look at Christmas as a substitute for New Year’s Day. Since the Reformation, Protestants had dismissed Christmas as another artifact of Catholic ignorance and deception: not only was the New Testament silent on the date of Christ’s birth, they noted, but the Church had picked December 25 to coincide with the beginning of the winter solstice, an event traditionally associated with wild plebeian bacchanals and challenges to authority. Wellbred New Yorkers in the early nineteenth century weren’t so vehemently opposed to Christmas as Petrus Stuyvesant had been, and often marked the day with private family devotions, dinners, and “Christmas logs.” Patricians with New England roots knew that churches there had recently begun a movement for public worship on December 25 to counteract the spread of popular rowdyism. Then came Washington Irving’s Sketch Book (1819), a collection of short stories that not only gave to American literature the characters of Ichabod Crane and Rip Van Winkle but sparked widespread interest in Christmas as a cozy domestic ritual.

It remained only to get Sancte Claus into the picture, and that was the achievement of another of Pintard’s friends, Clement Clarke Moore (still fuming over the intrusion of Ninth Avenue into his beloved country estate, Chelsea). During the winter of 1822, Moore wrote a poem for his children entitled “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” arguably the best-known verses ever written by an American. Moore’s saint was an obvious derivative of Irving’s—“a right jolly old elf” who sneaks down the chimney of a gentleman’s house in the dead of night, not to rob him but to put toys in the stockings hung up by his children. Moore had him arrive on December 24, however, a small revision that deftly shifted the focus away from Christmas Day with its still-problematic religious associations.

A friend sent “Visit” to an upstate newspaper for publication, other papers picked it up, and within a decade it was known throughout the country (though Moore didn’t acknowledge writing it until some years later). In the meantime, genteel New Yorkers embraced Moore’s homey, child-centered version of Christmas as if it they had been doing it all their lives. “A festival sacred to domestic enjoyments,” the papers called it; a time when men “make glad upon one day, the domestic hearth, the virtuous wife, the innocent, smiling merry-hearted children, and the blessed mother.” In 1831, his earlier promotion of December 6 long since forgotten, Pintard asserted that the new rituals of Christmas were of “ancient usage” and that “St. Claas is too firmly riveted in this city ever to be forgotten.” (Christmas trees reached New York in the mid-thirties, courtesy of German Brooklynites; they were popularized by Catharine Maria Sedgwick, the novelist, who wrote the first American fiction including a Christmas tree in 1835.)

Despite its prominence in the consciousness of upper-class New Yorkers, the ideal of a genteel household—quarantined from the rough-and-tumble of commerce by distance, nurturing mothers, and yuletide cheer—often collided with the day-to-day realities of household affairs. Only the very wealthiest women, for example, had enough servants to relieve them entirely of cooking, cleaning, laundering, and other menial chores. John Pintard employed an all-purpose maid, but his wife and younger daughter were responsible for sewing, tailoring, preserving food, baking, liming the basement, whitewashing fences, clearing the yard, and basic carpentry. Increasingly, moreover, even rich families were replacing lifetime African-American retainers with part-time or seasonal help, typically Irish, and the mistress of the house needed to be as adept as her husband in recruiting and managing a wage-labor force. Everyone had stories of servants who stalked out in a dispute over their duties or pay or were lured away by promises of better accommodations. When John Pintard’s “unfaithful, ungrateful” maid left without notice, he found it “vexatious in the extreme” and (as was his wont) formed an organization in 1825 to deal with the entire “problem”—the Society for the Encouragement of Faithful Domestic Servants.

Business and public affairs were no more absent from the genteel home than labor. If the back parlor remained a family sanctum, the dining room and front parlor, where children were allowed only on Sunday mornings, hosted a good deal of work-related socializing. New York gentlemen often entertained one another at home and although Mrs. Trollope deplored the exclusion of women from these male affairs as “a great defect in the society” that “certainly does not conduce to refinement,” they were nonetheless a vital forum for the private exchange of views about economics and politics.

Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Fiedler and family at their home on Bond Street, painting by F. Heinrich, 1850. “The houses of the higher classes,” Frances Trollope wrote, were “extremely handsome, and very richly furnished” with the chandeliers, mirrors, carpets, and upholstered furniture that here attest to the Fiedlers’ respectability. Note also the pianoforte and—partially concealed by the Greek Revival ionic columns in the background—a Christmas tree. Not depicted, almost inevitably, are the servants whose labor was essential to maintaining these cozy domestic sanctuaries. (Photograph courtesy of Mr. Nicholas L. Bruen)

Women too utilized the parlor, for Bible readings, charity meetings, after-church teas, and the formal “morning calls” that maintained class boundaries by defining the people to whom one was, or was not, “at home.” For both sexes, moreover, every room accessible to outsiders was a stage for displaying the family’s wealth and sophistication. The most refined houses boasted pianofortes, which cost as much as six hundred dollars (more than a year’s wages for a carpenter or cabinetmaker) and were the basis for fashionable “at home” musical performances. Technologically advanced households also had coal-burning stoves, iceboxes, and gas lights, whose installation and upkeep exceeded the annual rent bill of many poor families.

The genteel parlor was likewise an important adjunct to the upper-class marriage market. Well-bred young men and women took note of one another during the annual cycle of assemblies, balls, and concerts, but a proper courtship didn’t begin until a “beau” gained the privilege of an “at home” visit. Such occasions were closely chaperoned and, as James Fenimore Cooper observed, governed by taboos so strict that a young woman would assume “a chilling gravity at the slightest trespass.” And not without reason, for much hung in the balance: a careless match could plunge an entire family into dishonor and ruin; a good one would bring money and connections sufficient for generations of preeminence. Here, too, Yankees and Knickerbockers saw eye to eye, and many a Yankee entrepreneur won his future in the parlor of a genteel Knickerbocker girl.

The permeability of the membrane separating the spheres of family and business was no less apparent at Christmas, the holiday dedicated to domesticity. By 1830, if not earlier, the week before Santa arrived had become a time for heavy shopping at toy shops, confectionery stores, jewelers, and booksellers. Shopkeepers flogged luxury goods few people purchased at other times of the year, and indeed the season helped legitimate indulgence for a culture that was still consumption-shy. In this context as well, genteel households managed both to lock out commerce and simultaneously contribute to its relentless advance.

August 16, 1824, a fine summer day: thousands of New Yorkers jammed the Battery to greet the flotilla of steamboats escorting the marquis de Lafayette to Manhattan for the start of a year-long tour of the United States. Stepping ashore at two P.M., the aging Revolutionary hero was swept in magnificent procession out the Battery’s Greenwich Street gate, through Bowling Green, and up Broadway toward City Hall, preceded by mounted buglers. The route was thick with tens of thousands of cheering men and ladies waving handkerchiefs, while a rain of flowers fell from the upper windows of nearby buildings. After a reception at City Hall, Lafayette was settled at the City Hotel and feted at a state banquet that concluded with a balloon ascension.

Any resemblance to an ancient Roman triumph was completely intentional. Conscious of the hoary canard that republics were ungrateful to their benefactors, the Corporation of the City of New York had set out to arrange a reception that, while avoiding unrepublican “pomp” and “ostentatious ceremonies,” would nevertheless pay magnificent homage to one who had labored selflessly for the common weal. A committee chaired by the civic patriarch William Bayard (assisted, inevitably, by John Pintard) devised a schedule that honored Lafayette and showed off the city to best advantage. Before setting out on his U.S. tour, he took in a gala performance of Twelfth Night, endured another state dinner at the City Hotel, and attended a reception at the Rutgers mansion. He visited the Navy Yard. He met with clergymen, officers of the militia, and delegates from the French Society and the New-York Historical Society.

Lafayette swung through New York again the following July on his way south. Speaking at the city’s Independence Day celebrations, he assured his listeners that of all the wondrous improvements he had seen on his journey thus far, “Nowhere can they be more conspicuous than in the state of New York, in the prodigious progress of this city.” Another busy week ensued, including a trip to Brooklyn, where he picked up and kissed six-year-old Walter Whitman (or so the poet insisted in later life). Lafayette returned to New York a third and final time in early September for another round of sightseeing (Columbia College, the Academy of Arts, the hospital, the almshouse) and a spectacular sendoff that was soon to become the talk of the country: a grand fete at Castle Garden on the evening of September 14, at which six thousand guests danced until two in the morning.

For upper-class New Yorkers, Lafayette’s three visits, each carefully staged-managed, constituted a running advertisement for the legitimacy of the municipal social system. They demonstrated that huge crowds of citizens could assemble peacefully to honor a national hero—or, as Cadwallader Colden forthrightly put it, that an “exhibition of bayonets is not essential to the preservation of order in New York.” They affirmed, too, that even the city’s wealthiest residents hadn’t forgotten their Revolutionary antecedents and remained fully committed to the cause of constitutional republicanism around the world.

Not coincidentally, rich New Yorkers were already deeply involved in marshaling popular support for the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman empire. Since raising the standard of revolt in 1821, the Greeks had won support from radicals and reformers throughout Europe by presenting themselves both as heirs of Athenian democracy and as Christian crusaders against the heathen Turks. In 1823 a meeting of sympathetic New Yorkers set up a Greek Committee, chaired by William Bayard, to raise money for the rebels, while another group, headed by Chancellor James Kent, appealed to Congress to recognize Greece as an independent nation. They were soon joined by a long line of wealthy Yankees and Knickerbockers.

By the mid-twenties, even as Lafayette made his triumphant rounds of the city, New York was in the grip of a Greek mania. The Greek Ladies of Brooklyn and New York erected a twenty-foot Grecian Cross on Brooklyn Heights. Churches and schools took up collections, theaters gave benefit performances, and tickets were sold for a military ball (“as exclusive an affair as was practicable”). Politicians made speeches, and poets churned out verses on Greek themes; Mordecai Noah wrote a play, The Grecian Captive or the Fall of Athens, in support of “the present struggle for liberty in Greece.”

There was money to be made as well as raised. In 1824 Greek agents in London asked LeRoy, Bayard, and Company to arrange manufacture of two fifty-gun frigates in New York. The firm placed the order with Eckford and with Smith and Dimon, two local yards, and once again a fund-raising frenzy swept the city. In October 1825, with the ships ready to sail, the Greeks discovered the final bill was twice as high as the price they’d been quoted, having been inflated by fat commissions and brokerage fees, and the builders refused to release the vessels until the sum was paid. The rebels were forced to sell one of the frigates to the U.S. Navy in order to redeem the other. Both purchasers soon discovered that the vessels had been constructed using cheap green timber rather than the expensive live oak stipulated in the contract. The ensuing scandal embarrassed old Bayard, head of the Greek Committee, though his sons appear to have been the ones at fault. When the old man died in 1826, the business failed almost immediately.

None of this dampened the enthusiasm of the propertied classes for international republicanism. In 1830, when the July Revolution in France toppled the regime of Charles X, a committee chaired by Philip Hone chose Evacuation Day, November 25, for a massive show of solidarity. Thousands of merchants, manufacturers, and tradesmen, many accompanied by elaborately decorated floats, turned out to march from the Battery up to a rally at the Washington parade-ground. Several old Revolutionary soldiers were present as well, among them John Van Arsdale, who had pulled down the last British flag in 1783 and now carried the banner he had hoisted in its place.

The clamor for Greek independence (nudged along by a recent British fad for Greek antiquities) had meanwhile sparked a demand among wealthy New Yorkers for buildings designed to look as if they belonged on the Acropolis in ancient Athens. Greek Revival architecture, as it came to be known, seemed particularly well suited to the United States. Its basic elements—massive fluted columns, triangular pediments, heavy cornices—created a highly satisfying sense of kinship with the Athenian city-state famed as the birthplace of Western democracy. The first full-blown example of Greek Revival architecture in America was the headquarters of the Bank of the United States in Philadelphia, a Parthenon-like edifice completed in 1824. Only a few years later, New York’s booming financial district got its first taste of the new style in Martin Euclin Thompson’s Phoenix Bank.

The spread of Greek Revival architecture in the city quickened with the arrival of a Yankee engineer-architect named Ithiel Town. Town moved down from New Haven in the mid-twenties, certain that New York was about to become the pivot of the republic—and that its rich patricians would pay generously for the new style. His first commission, a Greek Doric design for the New York [later renamed Bowery] Theater, came in 1826. The following year he went into partnership with Thompson to form the city’s first professional architectural firm, Town and Thompson, which quickly produced the Church of the Ascension on Canal Street (1827-29), among other notable structures, as well as renovations to St. Mark’s in the Bouwerie (1828).

Thompson left Town in 1829 and went on to fame as the architect of the gracefully proportioned row houses on Washington Square North (1829-33) and, with another newcomer named Minard Lefever, of Sailors’ Snug Harbor on Staten Island (1831-33)—both still among the best surviving examples of Greek Revival building in the country. Town had meanwhile teamed up with Alexander Jackson Davis, a native New Yorker nineteen years his junior. Davis was a skilled architectural draftsman who had thrived by furnishing plans and elevations to the burgeoning ranks of speculative builders. After Davis won a commission to remodel the old almshouse—New York’s first civic building in the new style—Town took him on as a partner and opened an office in the Merchants’ Exchange. The two soon made Greek Revival architecture as prevalent a symbol of genteel New York as Santa Claus. Their temple-fronted churches and columned town houses sprang up throughout Greenwich Village, Chelsea, and other fashionable new neighborhoods. The Greek Revival facade that Town designed for Arthur Tappan’s store at Pearl and Hanover streets in 1829 was the first to make use of post-and-lintel construction, so obvious an improvement for displaying as well as storing wares that it quickly became the norm for downtown commercial buildings.

Ever since the 1790s, De Witt Clinton and a small handful of like-minded gentlemen had been urging more systematic support for the arts and sciences—equally to encourage republican virtue among the people and to counter the city’s reputation for benighted money-grubbing. Culture was as much an “internal improvement” as the Erie Canal, they argued, and equally the responsibility of government. In 1816 the Common Council agreed. New York had “too long been stigmatized as phlegmatic, money making & plodding,” the aldermen admitted, and they determined to “speedily retrieve the reputation of our City,” by providing “municipal aid” to cultural institutions as Edinburgh, London, Paris, and Amsterdam, and other European capitals did. Moving inmates of the Chambers Street almshouse up to a new facility near Bellevue, they gave McComb’s three-story 1797 building a new name: the New York Institution of Learned and Scientific Establishments. The idea, as Pintard put it, was that “by concentrating all our resources we may give a greater impulse and elevation to our intellectual character.”

Seven prominent “establishments” agreed to take up quarters in the Institution: the recently reorganized American Academy of Fine Arts, the New-York Historical Society, the new Literary and Philosophical Society, the New York Society Library, John Scudder’s Museum (successor to the old Tammany Museum), the U.S. Military and Philosophical Society, and John Griscom’s Chemistry Laboratory. (Not all of them actually moved in. The Society Library, for one, kept its formidable collection of twenty thousand volumes down on Nassau Street.)

The leadership of the institution’s member organizations was drawn from a small, frequently overlapping group of affluent merchants and lawyers. As they understood matters, elevating the city’s intellectual character required them not simply to patronize creativity but to ordain and enforce standards for it as well. So in 1816, when John Vanderlyn asked the academy for space to exhibit a reclining nude entitled Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, the horrified members turned him down on the grounds that the painting offended public decency. Their notions of good art ran to the inspiring historical canvases of John Trumbull, whose full-length portraits of Washington, Hamilton, Jay, and other worthies already graced City Hall—and who, as it happened, had just been elected president of the academy. In 1819, when Trumbull finally completed his Declaration of Independence, destined for the Capitol in Washington, the academicians proudly let the public in for a preview (at twenty-five cents a head).

Vanderlyn, in the meantime, had taken his revenge by soliciting money from Astor and a hundred other gentlemen to build his own gallery on Chambers Street, directly east of the institution. This was the Rotunda, a Pantheon-like building, fifty-six feet in diameter and capped by a thirty-foot dome. Its main attraction, which went on display in the summer of 1819, was Vanderlyn’s own Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles, twelve feet high and 165 feet long. The public wasn’t impressed, and critics advised him to depict American rather than European scenes in the future.

In 1824 the effort to improve the intellectual climate of New York took a new turn when Pintard and a number of its “wealthiest and most learned” citizens met at the City Hotel for the purpose of creating an athenaeum. Modeled on similar organizations in Liverpool (1798), Boston (1807), and Philadelphia (1814), the New York Athenaeum was to be a “genteel place of resort” for the perusal of books, magazines, and newspapers. It would also sponsor lectures, which would be open to women as well as men, by prominent artists, writers, and scientists. The lecture series started up almost immediately in the chapel of Columbia College: Gulian Verplanck speaking on political economy, Professor John McVickar on the philosophy of mind, Professor James Renwick on applied mechanics, and the Rev. Jonathan Wainright on oratory, among others, drawing audiences “distinguished for fashion, beauty, and accomplishments.” As intended, the athenaeum subsequently opened a public reading room at the corner of Broadway and Pine that became quite popular (Tocqueville and Beaumont dropped by almost every day during their visit to the city).

The machinery of genteel cultural legislation and patronage made its most enduring contribution to the city, however, by launching the artistic careers of newcomers like Samuel Finley Breese Morse and Thomas Cole. Morse, an itinerant painter from New England, moved down to the city in 1823 because he believed that the “influx of wealth from the Western canal” would soon make it a good place to look for commissions (and because he hoped to succeed the aging Trumbull as president of the academy). It was slow going at first. “This city seems given wholly to commerce,” Morse grumbled. “Every man is driving at one object, the making of money, not the spending of it.” But in 1825, thanks to Philip Hone, Morse was tapped to paint a portrait of Lafayette for City Hall. His dynamic rendering catapulted him to fame, and commissions poured in. Dr. David Hosack of the academy asked Morse to do anatomical paintings for his medical classes. The athenaeum made him its secretary and invited him to lecture on the arts. By 1831 Morse had come round to the view that “New York is the capital of our country and here artists should have their rallying point.”

Cole’s was a similar story. Born in 1801 in Lancashire, England, where his father was a failed woolens manufacturer, Cole came to the United States in 1818 and became an itinerant painter of landscapes and portraits. In 1824 he came to roost in a Greenwich Street garret and began to exhibit scenes of upstate New York in local shops. Three of his works, displayed in the window of William Colman’s bookstore, caught the eye of Trumbull, who reported his discovery to engraver Asher B. Durand and the playwright-painter William Dunlap. Each bought one, and they exhibited their acquisitions at an academy show in the New York Institution, where they caused considerable excitement. Philip Hone, William Gracie, Gulian Verplanck, and David Hosack ordered paintings from Cole for themselves, and Cole headed back upstate to produce more. He returned with a new batch, sold them at the academy, and left again for the mountains—a cycle that would be repeated over the next four or five years.

Like Morse and Cole, writers William Cullen Bryant and James Fenimore Cooper found the support of New York patricians crucial at the beginning of their literary careers. Bryant, originally from the Berkshire town of Cummington, Massachusetts, had been practicing law unhappily in Great Barrington before he came to Manhattan in 1825 to promote a book of poems and start life over as a journalist. The athenaeum hired him to edit its New-York Review and Athenaeum Magazine; the venture didn’t flourish, and Bryant (echoing Vanderlyn and Morse) began to complain that “nobody cares anything for literature” in New York, where the only man considered a genius was “the man who has made himself rich.” Then William Coleman, editor of the Evening Post, took Bryant on as his assistant. In 1829 Coleman died, and the thirty-four-year-old succeeded him as editor, giving “America’s First Poet” a secure base of employment.

Cooper had grown up on his family’s extensive Cooperstown estate, got himself kicked out of Yale, and drifted into the navy. When his father died he inherited an ample fortune and seemed destined for the life of an Episcopal squire in Westchester. But in 1821, now thirty-one, Cooper walked into the New York office of publisher Charles Wiley, carrying the manuscript of a novel about the Revolution entitled The Spy. Its publication made him famous and prompted him to move to the city to be near his publisher. Over the next six years he churned out The Pioneers (1823), The Pilot (1823), The Last of the Mohicans (1826), and The Prairie (1827). Meanwhile, in 1822, he began a series of midday get-togethers for writers, artists, and interested gentlemen in the back room of Wiley’s New Street bookstore. First known as Cooper’s Lunch, the conclave soon became the Bread and Cheese Club, named after the formalized balloting system for electing new members (a bit of bread signified acceptance, a piece of cheese rejection).

In one sense, Bread and Cheese was only the latest in a long line of fraternities organized in the city by dabbling amateurs and self-taught connoisseurs among the elite—most recently, the Knickerbocker wits who had held court at the Shakespeare Tavern and preserved their repartee in print, as much for their own amusement as for the public’s. Yet it also contained the germ of something quite new. Among its members were artists and writers who regarded their crafts as full-time vocations, not hobbies to be pursued in moments snatched from law or commerce, and the club helped them forge a new kind of professional identity. Morse, Cole, Bryant, Durand, John Wesley Jarvis, and Dunlap cemented friendships there, as did Fitz-Greene Halleck, versifier and man about town; Gulian Verplanck, writer on law and theology, editor of Shakespeare, and spokesman of the New York Dutch; and James Kirke Paulding, still grinding out material for Salmagundi, his old venture with Washington Irving (who, now abroad, was a Bread and Cheese man in absentia).

Although the club failed to survive Cooper’s departure for a long European sojourn in 1826, the growing sense of solidarity it bred among professional artists had already laid the foundation for a confrontation with Trumbull’s Academy of Fine Arts. When some young painters sought access to the academy’s collections to practice their drawing, Trumbull, full of patrician hauteur, barred the way and advised them to “remember that beggars are not to be choosers.” Late in 1825 the painters struck back by founding their own organization, the New York Drawing Association, with Morse as president and Cole and Ithiel Town among the founding members. The following year it became the National Academy of Design, which unlike the Fine Arts Academy was to be run strictly by and for artists—“on the commonsense principle,” Morse wrote, “that every profession in a society knows what measures are necessary for its own improvement.” Artists all over the country came to think of the National Academy’s annual exhibition as the most desirable place to show their latest work. In a similar spirit, Morse, Bryant, Cole, Durand, and Verplanck, with other professional writers and artists, came together in 1829 to form the Sketch Club.

All this was a frontal assault on the notion—an article of faith for men like Pintard and Clinton—that the propertied classes were competent to steer artistic and literary production for the greater municipal good, and it marked the beginning of a decline in genteel cultural authority. Artists had effectively shifted relations with the Hones and Hosacks, Gracies and Griswolds to a less paternalistic, more market-mediated footing, which in turn summoned professional “critics” into being. Before 1825 literary magazines hadn’t covered the negligible fine arts world; now the weekly New-York Mirror began reviewing the annual exhibitions at the National Academy and reproducing some of the artwork via engravings and woodcuts.

The older model of patrician patronage, having helped foster a cultural community, now began to fade away. As early as 1828 the athenaeum abandoned its lecture program because too many well-to-do families were moving too far uptown (the reading room was eventually absorbed by the Society Library). The New-York Institution collapsed when the Common Council, on the recommendation of councilman James Roosevelt in 1830, refused to renew its lease on the almshouse and took the building over for municipal offices (after renovations by Alexander Jackson Davis). The Literary and Philosophical Society dissolved shortly thereafter, followed by the Academy of Fine Arts itself.

For all their differences, patricians and artists had in common a lack of interest in New York City as a literary and artistic subject. Instead, they echoed the pastoral romanticism currently in vogue among European intellectuals (neither Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, nor Keats located most of a major poem in contemporary London). Addressing the Academy of Fine Arts in 1816, Governor Clinton suggested that exposure to the “wild, romantic, and awful scenery” of the American wilderness had the power “to elevate all the faculties of the mind, and to exalt all the feelings of the heart” (both of which, by implication, suffered in the nation’s cities). Within a decade, thanks less to Clinton’s oratory than to canny steamboat operators and the appearance of fashionable rustic “resorts” far removed from Manhattan, hundreds of affluent New Yorkers left town every summer to experience the restorative powers of uncontaminated Nature. Their favorite destination was the Catskill Mountain House (1824), the first successful hilltop hotel in the United States and a must-see stop for Europeans on the American Grand Tour. Ladies and gentlemen disposed to visit the seashore went to Coney Island House (1824), a retreat famed for its first-class accommodations, well-prepared meals, and up-to-date bathing facilities.

New York writers fostered the new sensibility with a widening stream of novels and poems that depicted the American wilderness as an antidote to alienated urban life (rather as the refined home was held up as a sanctuary from city hurly-burly). Cooper’s frontier romances were an extended paean to the nobility of the Catskills, while Irving, who had never been closer to the forest primeval than the deck of a river sloop, wrote lovingly of the supernal beauty of the Hudson highlands and their quaint inhabitants, who, like Rip Van Winkle, belonged to an earlier, less complicated time. Bryant, having fled the countryside for the big city, built an entire career on poetry that taught respectable merchants and bankers to yearn for woods, pastures, and streams.

Cole and his many disciples would convey the same message with even greater force in landscapes where all evidence of human presence was dwarfed by scenery so majestic and inspiring as to seem almost other-worldly—a point of view that garnered princely commissions from the very land speculators, canal boosters, and manufacturers who were doing their best to tame that scenery in the name of trade and commerce. What was more, some of Cole’s earliest and best-known paintings—Falls of Kaaterskill (1826); The Clove, Catskills (1827); Scene from “The Last of the Mohicans” (1827)—were of subjects already immortalized, or soon to be, by Irving, Cooper, and Bryant. Though Cole’s representations carefully deleted all signs of the new tourism, Catskill resort operators drew on his panegyrics, and those of Irving and Cooper, for use in advertisements. James Kirke Paulding, in his The New Mirror for Travellers; and Guide to the Springs (1828), urged “the picturesque tourist” not only to stay at the Mountain House but also to buy paintings from Cole and other landscape artists.

One of the few ways in which New York’s artists were willing to appreciate the city was by turning to its past—or a sentimentalized nostalgic version thereof. Like Home and Nature, History seemed a sanctuary from the hurried present. In 1827 the New-York Mirror began a series called “Antiquities of New York” that combined wistful, Irvingesque stories of New Amsterdam with engravings of old Dutch buildings by Alexander Jackson Davis.

Bryant often escaped from downtown to explore groves along the Hudson or ramble past old Dutch farms in Brooklyn, looking for traces of history. In 1829-30, he and Gulian Verplanck wrote “The Reminiscences of New York,” published in two successive issues of their annual, The Talisman. The fictive narrator of the piece fretted about the lack of “chivalric” associations common in Virginia or South Carolina: “I do not know whether any romance actually remains in New-York at the present moment,” because “the progress of continual alteration is so rapid” that a few years can “sweep away both the memory and the external vestiges of the generation that precedes us.” European cities changed little from decade to decade, but the narrator, having returned to Manhattan after an absence of just two years, found “every thing was strange, new and perplexing, and I lost my way in streets which had been laid out since I left the city.”

Worse still was the prevailing antihistoric sensibility, evidenced by even so distinguished a citizen as Cadwallader Colden. In 1825, when hailing the opening of the Erie Canal, Golden had remarked: “We delight in the promised sunshine of the future, and leave to those who are conscious that they have passed their grand climacteric to console themselves with the splendors of the past.” Bryant and Verplanck suspected that “New-Yorkers seem to take a pleasure in defacing the monuments of the good old times, and of depriving themselves of all venerable and patriotic associations.” All the more imperative, therefore, to preserve any remaining “fragments of tradition and biography,” and the authors accordingly chronicled the little church where Whitefield used to preach, the site of Washington’s inauguration, Jefferson’s home on Cedar Street.

Cooper too cherished the few Dutch dwellings that remained—“angular, sidelong edifices, that resemble broken fragments of prismatic ice”—regretting a growth rate that forced old buildings “out of existence before they have had time to decay.” Asher Durand would try to conjure them back into existence by painting picturesque tableaux of New Amsterdam’s past—as interpreted by Washington Irving—in works such as The Wrath of Peter Stuyvesant.

In the end, however, the ties that bound many Knickerbocker artists to the city would prove tenuous indeed. When Cooper returned from Europe, he withdrew to the old family manor at Otsego Lake. Irving would establish himself as a country squire at an old Dutch farmhouse near Tarrytown. And Cole retreated to a country home just north of Catskill. Nevertheless, New York’s merchants, financiers, and lawyers were delighted with their artists’ achievements. Given “the growing Fame” acquired by Irving and Cooper, Philip Hone believed, in time the city would “become as celebrated for taste and refinement, as it already is for Enterprise and public spirit.”

Indeed, the Manhattan Medici had every reason to feel proud about the direction the civic ship was taking under their collective captaincy. They felt secure in their position as patrons of the arts and sciences, directors of economic enterprise, chief celebrants at municipal pageants, leaders in the political arena, and owners of most of the city’s terrain. True, there were intramural debates between Knickerbockers and Evangelicals, but none had proved sufficiently divisive to override their common republican conviction that they could and should assume responsibility for the common good. But this serene self-confidence in their ability to speak for the city as a whole, without rebuke from below, was at the same time being called into question in a series of confrontations with obstreperous lower orders, who, day by day, were developing opinions and judgments considerably at variance with their own.