On New Year’s Eve, as the city bade farewell to 1827, several thousand workingmen—laborers, apprentices, butcher boys, chimney sweeps—set out from the Bowery on a raucous march through the darkened downtown streets, drinking, beating drums and tin kettles, shaking rattles, blowing horns. The crowd headed down Pearl Street into the heart of the city’s commercial district, smashing crates and barrels and making what one account described as “the most hideous noises.” From there the marchers wheeled across town to the Battery, where they knocked out the windows of genteel residences and attempted to tear down the iron railing around the park. At two in the morning they tromped up Broadway, just in time to harass revelers leaving a fancy-dress ball at the City Hotel. A contingent of watchmen appeared but, after a tense confrontation, gave way, and “the multitude passed noisily and triumphantly up Broadway.”

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, New York’s propertied classes had more or less tolerated such instances of plebeian revelry because they were relatively harmless and (as Petrus Stuyvesant found out) difficult to uproot. Even after the Revolution, “Callithumpian bands”—echoing ancient European traditions—had continued to parade about, beating on pans, shouting and groaning, mocking the powerful and overly dignified. Respectable opinion had grown steadily less tolerant of self-organized plebeian frolics, however, partly because they affronted genteel notions of correct behavior, and partly because every year they became more truculent, more defiant of authority. It was one thing for great throngs of working people to rejoice noisily at Lafayette’s visit or the opening of the Erie Canal, civic ceremonies orchestrated by gentlemen; it was quite another for rowdies to take over the streets, wantonly destroying property and terrorizing law-abiding citizens.

The very next year, accordingly, Mayor Walter Bowne ordered the watch to disperse all crowds on New Year’s Eve, and there was no Callithumpian procession. But such street confrontations would not fade away, in part because they were rooted in widening divisions between working-class wards and gentry precincts over the proper canons of public and private behavior.

On point of divergence concerned the seemliness of living where one worked. While some prosperous entrepreneurial artisans had joined the gentility in commuting to their place of business from uptown bedroom communities, few master craftsmen, journeymen, or unskilled laborers could afford the expensive new omnibuses. They stayed, accordingly, in craft-based communities, within which they could walk to work.

Greenwich Village remained one such house-and-shop stronghold. Especially after the Christopher Street pier (1828) became the main point of entry for building materials used in transforming the uptown cityscape, the area grew dense with carpenters, masons, painters, turners, stonecutters, dock builders, and street pavers. Brooklyn Village too continued as a working community based on agricultural processing and transport, its streets lined with household-shops of coachmakers and coopers, saddlers and blacksmiths. Butchers remained prominent: one was elected first village president. By the mid-1820s the booming hamlet had more than tripled its prewar population, creating additional jobs for resident carpenters and masons.

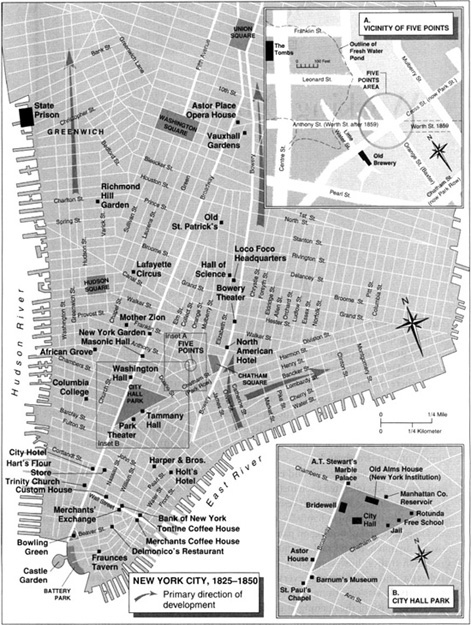

Corlear’s Hook still hosted the shipwrights, sailmakers, coopers, and chandlers whose livelihoods depended on the nearby shipyards—along with sailors, including a group of Chinese tars on Market Street who constituted the first significant Asian presence in New York. The Five Points also housed a great array of trades: breweries, potteries, and tobacco manufactories; tailoring, shoemaking, and printing establishments.

Bowery Village remained notorious for the stomach-turning stench of its slaughterhouses and lanyards. As late as 1825, upstate drovers like Daniel Drew were herding an estimated two hundred thousand head of cattle across King’s Bridge each year and making their way, accompanied by hordes of pigs, horses, and bleating spring lambs, down Manhattan to Henry Astor’s Bull’s Head Tavern and adjacent abattoirs. A butcher who acquired an exceptionally fine cow would then parade it through the streets, preceded by a band and followed by fellow butchers in aprons and shirtsleeves, stopping before homes of wealthy customers, who were expected to step out and order part of the animal.

Some of those customers, bolstered by gentry families filtering in from the lower wards, wanted to transform the Bowery into a more genteel neighborhood. Taking aim at the stink, the endless whinnying, lowing, and grunting, and the occasional steer running amok and goring passers-by, they set about driving the Bull’s Head from the area. In the mid-1820s, an association of socially prominent businessmen bought out Henry Astor and dismantled his enterprise. (A new Bull’s Head opened in semirural surroundings at Third Avenue and 24th Street and soon attracted cattle yards, slaughterhouses, pig and sheep pens, and a weekly market; the area became known as Bull’s Head Village, the city’s northern frontier.) Meanwhile, in place of the old tavern, the consortium set about erecting Ithiel Town’s splendid Greek Revival playhouse—the New York (soon to be Bowery) Theater. Mayor Philip Hone hailed the transformation as marking “the rapid progress of improvement in our City.” But neither theater nor street was destined for gentility, and the Bowery would soon evolve into an entertainment strip for surrounding communities.

Within such working-class neighborhoods, the families of small masters, journeymen, and laborers lived in housing far different from the spacious abodes rising along Bond Street. Some speculative builders did raise modest but decent worker residences along streets carved out of the old De Lancey estate—many of them, including Eldridge, Ludlow, Forsyth, and Chrystie, named for military and naval heroes of the late war—or along Ist to 6th streets, the newly opened first fruits of the grid, which ran down to the East River.

However, with low incomes and expensive transportation tethering working people downtown, it proved equally profitable to exploit the captive market by cramming renters into preexisting spaces. In these aging structures, conditions varied from decent to squalid, but even at their best, the coal stoves, gas lights, iceboxes, and other improvements on display in the residences of the uptown gentry were unheard of. People made do with candles and oil lamps or scavenged winter wood along upper Manhattan’s roadsides. Few households had a sufficient number of privies. Many laborers relied on cheap ceramic chamber pots from England, except for the very poor, who, in the phrase of the day, were “without a pot to piss in.” Better-off families might have bedsteads or display clocks and prints on the wall. The poorest lived together in a single room, furnished with little more than a straw mattress, a few cast-off chairs, and a sawed-off barrel top for a table.

The plebeian quarters grew steadily more crowded, and the Sixth Ward’s Five Points became the most densely packed neighborhood in the city. Its two- and three-story buildings, designed originally as one-family houses, housed an average of thirteen people as early as 1819, and by some estimates, building density doubled by the early 1830s. On Mulberry Street, homes with thirty-five occupants were not unknown; 122 Anthony housed eighty-three residents; 10 Hester Street contained 103; later in the decade, a brewery erected back in 1797 on the shores of the Fresh Water was transformed into a boardinghouse (known to all as the Old Brewery) that housed several hundred people. The mushrooming number of tenants in the area became overwhelmingly evident each Moving Day—by 1820 a scene of utter pandemonium, with thousands of people relocating at once, clogging the streets with wagons full of household possessions. It looked, Mrs. Trollope observed, as if the population were “flying from the plague.”

Within working-class neighborhoods, in further contrast to the more “refined” parts of town, women’s labor was deemed indispensable. Given the declining fortunes of proletarianized males, and employer calculations of a “living wage” that implicitly included the value of women’s unpaid domestic labor, many families were unable to make ends meet without the contributions of wives and children. A skilled wife whittled down the family’s cash expenditures. She hauled in water and firewood, lugged out waste and garbage, washed, mended, and made clothes, tended the sick, and raised the children, passing on values of hard work, honesty, loyalty to family, and neighborliness.

Laboring women did not dress up and pay each other formal parlor visits—they had no parlors—but they socialized through open windows and dropped in at one another’s kitchens, children in tow, to exchange gossip and information. Neighbors intervened in quarrels, sat up with sick infants, swapped news of market bargains, and helped out in crises (removing goods and furniture in case of fire, or rallying to block evictions). They also bickered and brawled in public, often engaging in extravagant donnybrooks that attracted crowds of cheering female onlookers.

Poorer women spent much of their time on the streets. Rather than retreat to domestic sanctuaries, they pawned and redeemed possessions, bargained with shopkeepers and peddlers for goods and credit, and scavenged for such discarded items as wood to burn, scraps of old clothing, and bits of food: one could scoop a week’s worth of flour from a broken barrel on the docks. Children were dispatched to forage for manufacturing wastes—nails and screws, old rope, broken glass, shreds of cotton plucked from wharves where southern packets docked. These could be sold to waterfront junk dealers, who in turn recycled them to iron founders, shipwrights, glassmakers, or makers of shoddy (the cheap cloth used in producing “slop” apparel for the poor).

Women worked hard to supplement a diet that consisted largely of bread and potatoes, corn and peas, beans and cabbage, and milk from cows fed on “swill”—byproducts of the city’s distilleries. In good times, they might add salt meat and cheese, a little butter, some sugar, coffee, and tea. But meat and poultry, though widely available in city markets, were expensive, even when purchased for a reduced price at the end of the market day. Many working-class wives therefore kept their own animals, notably pigs; lacking the space to board them, they let the hogs run free to scavenge for themselves. New York had long been infamous for its thousands of porcine prowlers, and when city fathers once again tried to sweep them from the streets, they touched off a raucous confrontation with poor mothers.

In 1818 Mayor Cadwallader Golden regretted that “our wives and daughters cannot walk abroad through the streets of the city without encountering the most disgusting spectacles of these animals indulging the propensities of nature.” Copulating and defecating porkers were a decidedly ungenteel sight, and their “grunting ferocity” could be dangerous to children. Golden empaneled a grand jury, which indicted a butcher, Christian Harriet, as a public nuisance for keeping hogs on the streets. He hired a lawyer, who contended that customary social practices, especially those “of immemorial duration,” could not be declared a public nuisance unless they violated standards held in common by the entire population. Pigs might offend ladies and dandies, “who are too delicate to endure the sight, or even the idea of so odious a creature.” But “many poor families might experience far different sensations, and be driven to beggary or the Alms House,” if deprived of this source of sustenance. Mayor Golden, in charging the jury, ruled the food factor irrelevant, and Harriet was convicted, establishing the absence of a legal right to keep pigs in the street. In 1821 the Common Council ordered a roundup of the swinish multitudes, but when pig-owning Irish and African-American women discovered city officials seizing their property, they mobilized, hundreds strong, and forcibly liberated the animals. Further hog riots broke out in 1825, 1826, 1830, and 1832, invariably ending with the women saving their bacon.

Women also earned hard cash for their households. They took in laundry, catered for boarders, or sewed pantaloons and vests as outworkers. Some worked as neighborhood midwives; others assisted their artisanal or shopkeeping husbands (butchers’ wives cut meat for market, junk-shop owners’ spouses took care of customers). Still others roamed the city streets as hucksters, hawking roots and herbs they had dug up, clams collected from beaches, muffins purchased cheap at the end of the previous day’s market, or berries and apples bought from country women at the edge of town. African American hot-corn girls were famed for their street cry: “Hot corn, hot corn, here’s your lily white hot corn / Hot corn all hot, just come out of the boiling pot.”

If a huckster could afford the fee, she rented a stall at a city market; if not, she circulated among the market’s customers. Those whose husbands could afford a backyard garden vended their own fruit and vegetables alongside the farmers’ wives selling pot cheese, curds, and buttermilk. Others opened small shops and sold cookies, pies, and sweetmeats of their own manufacture or retailed sundries, needles, and pins. The most destitute became ragpickers, perambulating the streets with hooks and baskets, poking into gutters.

The most common way for a woman to earn money, however, was to work as a domestic servant. The expanding number of upper-class dwellings and artisanal boardinghouses generated a huge demand for household help. Most white American women considered the job degrading. Apart from the harsh conditions, heavy work load, low pay, and often antagonistic relations with employers, the position was tainted by its associations with slavery and aristocracy. As a European visitor noted in 1819, “if you call them servants they leave you without notice.” When one domestic was asked to tell “your mistress” something, she exploded: “My mistress, Sir! I tell you I have no mistress, nor master either. . . . In this country there is no mistresses nor masters; I guess, I am a woman citizen.” Poor immigrant women, of necessity, were more willing to put up with the job; by 1826 a survey found that 60 percent of New York’s servants were Irish.

On the whole, however, while a woman’s wages might well be instrumental in keeping her household afloat, she could seldom earn enough to support herself on her own. This was particularly evident from the condition of wage-earning widows, who often lived closeted in tiny garrets or huddled in cellars or half-finished buildings, at the edge of destitution.

Working wards were different from genteel quarters, too, in their social composition. The Five Points in particular, as the Evening Post observed, was “inhabited by a race of beings of all colours, ages, sexes, and nations.”

Immigration boosted and diversified the population throughout the city, of course. The number of people living in what are today the five boroughs rose from 119,734 in 1810 to 152,056 in 1820 (an increase of 27 percent), and by 1830 it had jumped to 242,278 (up another 59 percent). The immigrant percentage of this growing populace rose steadily (6.3 percent in 1806 to 9.8 percent in 1819) until by 1825 over a fifth of the city’s residents were foreign-born.

Affluent arrivals might settle in the westside or uptown gentry wards, but relatively few were in a position to do so. Irish immigrants were getting steadily poorer. Ireland’s cotton and linen industries had collapsed with the end of wartime demand, generating widespread unemployment and destitution. Agriculture too sagged badly, once Britain’s wartime dependence on Irish foodstuffs slumped, cutting grain prices in half. Landlords responded by squeezing tenants, upping evictions, and consolidating lands, exacerbating a universal depression that led many to consider emigration to America “a Joyful deliverance.”

In 1818 alone, some twenty thousand Irish crossed to America. Most, as in colonial days, were Presbyterian and Anglican Scotch-Irish migrants from Ulster, many lured by jobs on roads and canals (especially the Erie). The Panic of 1819 slowed the rate of arrival, and emigration remained modest through the early 1820s. When packet ships between Liverpool and New York began providing cheaper passage, poorer Catholics from Ireland’s southern provinces began coming in growing numbers. Responding to intractable hard times at home and employment opportunities abroad, artisans, laborers, and single young women struck out on their own: passenger lists of vessels landing in New York in 1826 reveal that 62 percent of the Irish on board were traveling solo, and two-thirds of them were male. Many of those disembarking had exhausted their slender resources and were drawn—by its cheap rents and available jobs—to the Five Points’ soggy terrain, moving, as it were, from bog to bog.

The Points was home as well to many newly freed blacks. As the emancipation clock ticked toward its scheduled rendezvous with freedom on July 4, 1827, New York’s slave system collapsed. With immigration augmenting the supply of cheap free labor, manumissions mounted. The slave population of 2,369 in 1790 dwindled to 518 by 1820. African Americans declined as a percentage of New York’s total population (from 8.8 percent to 6.9 percent over the 1820s), reflecting the quickening pace of European immigration. But the absolute number of blacks in the city grew substantially, from 3,262 in 1790 to 13,976 by 1830, as freedpeople flocked in from surrounding rural regions.

Slavery’s grip had lasted longest in outlying farm country; as late as 1820 slaves constituted one-sixth the population of the agricultural communities of Kings County. When liberated, blacks relocated to nearby towns, flowing into Brooklyn Village, Jamaica, and Flushing’s Crow Hill. They were also drawn to Manhattan, by the availability of jobs as domestics, barbers, caterers, launderers, hucksters, wood sawyers, whitewashes, swill gatherers, ragpickers, chimney sweeps, and day laborers.

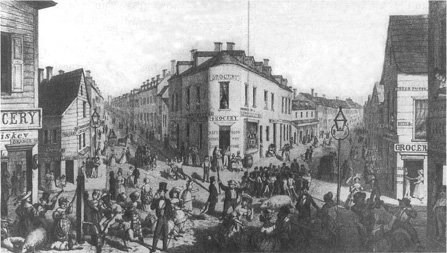

The Five Points, 1827 (from Valentine’s Manual, 1855). A cartoonish rendering of Paradise Square, heart of the Points—now the southwest corner of Columbus Park. Anthony Street (now Worth) heads diagonally off to the left while Orange Street (now Baxter) angles off to the right; Cross Street (later Park) runs left to right. The emphasis is on liquor, brawling, and pigs—all of which no doubt scandalized the dandyish outsider in the foreground. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

In Manhattan, some blacks settled in the northern countryside: in 1825 members of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church purchased parcels of farmland between 83rd and 88th streets and Seventh and Eighth avenues and erected several one-story unpainted cabins, forming the core of what would emerge as Seneca Village. A larger number moved to Greenwich Village, especially near Minetta Creek, where blacks had lived since Dutch days. Coachmen settled along a stable alleyway (it would evolve into Gay Street), but most took rooms in cramped and segregated boardinghouses. A bit farther south, still more blacks were drawn to the sunken Fifth Ward lots of the filled-in Lispenard Meadows, just behind New York Hospital. Others situated themselves along the strip of land spearing east along Chambers and Anthony (atop the Negro Burial Ground) or in the Five Points itself, where they occupied houses perched on insecurely reclaimed swampland, often in cellars, a scant few feet above water level, which flooded routinely.

Many of New York’s African Americans thus lived in close proximity to the newly arrived Irish and longer-established Anglo-Dutch working people—creating a mélange one genteel observer characterized as “the vilest rabble, black & white, mixt together.” There was no black ghetto, though some blocks were more single-hued than others. Bancker Street was notably black, overcrowded, and susceptible to disease. Of the 296 people killed by fever in the latter half of 1820,138 were African Americans, and half of these died in the vicinity of Bancker Street. So bad was its reputation that the Bancker family (Rutgers relatives) demanded their name be struck off, and in 1826 Bancker was renamed Madison.

The broad-spectrum quality of the working-class quarters extended to their religious institutions. Though the plebeian wards were theologically underserved in comparison to the thickly steepled gentry precincts, new houses of worship did arise, usually Catholic, Jewish, or evangelical Protestant, rather than Episcopal, Presbyterian, or Dutch Reformed (the dominant patrician denominations).

Even before the war, Father Kohlmann, Jesuit rector of St. Peter’s on Barclay Street, believed that many of his sixteen thousand parishioners were “so neglected in all respects that it goes beyond conception.” A second building was needed, especially for the growing number of Catholics “outside the city.” As New York had been made a see in 1808, Kohlmann decided to provide the forthcoming new bishop with a cathedral. A site was selected on the corner of Prince and Mott streets, north of the settled town, in an area of country villas and scattered farm dwellings. Joseph Mangin (coarchitect of City Hall) provided a design; wealthy laymen, among them Dominick Lynch and Cornelius Heeney, helped raise the funds; and in 1815, the same year in which Irish Dominican John Connolly arrived to serve as bishop of New York, St. Patrick’s Cathedral was dedicated. What is now referred to as Old St. Pat’s was, moreover, the largest church in the city.

Bishop Connolly also presided over the Church’s expansion into Brooklyn. In 1823 St. James Church, at the corner of Jay and Chapel streets, became the first Roman Catholic edifice in a community exclusively Protestant for two centuries. In that same year, Connolly invited Félix Varela y Morales to New York to begin a pastoral ministry among the Irish. They liked the Havana-born priest, an advocate of self-government and the abolition of slavery in Cuba, who published a bristling political magazine, El Haberno, and smuggled it down to Havana. Varela visited the sick and poor at all hours and purchased an old Episcopal church at Ann Street near the Five Points as a base of operations. By the time Connolly died in 1825, New York had thirty-five thousand Catholics, the great bulk of them poor Irish immigrants, and Gaelic working people dominated St. Patrick’s. The Irish had begun to be possessive of the ethnically mixed St. Peter’s too. When the Rev. John Dubois was installed as New York’s new bishop, Irish parishioners angrily opposed the move, stirring irate French Catholics to describe their Irish confreres as “an ignorant and savage lot.”

The House of Israel in New York City also fissured along ethnic, theological, class, and spatial lines. As of 1817 most of the city’s four hundred Jews still lived by the Battery, and Shearith Israel on Mill Street was the only synagogue in town. There was talk of relocating farther north: the edifice was showing its age; some wealthy members, including copper manufacturer Harmon Hendricks, had moved uptown, a long Sabbath walk away; and commercial development was making the area less desirable. Nevertheless, in 1818 the community rebuilt and enlarged the synagogue on its original site.

During the 1820s, however, Jews definitively migrated uptown, sorting themselves out geographically on class lines. The richer families generally stayed west of Broadway, the modestly well off settled between Broadway and the Bowery, and the poorest repaired to Centre, White, and Pearl streets, in or near the Five Points. When German immigration picked up—7,729 Germans arrived in the United States in the 1820s, and 152,454 in the 1830s—it included (beginning in the late 1820s) a substantial number of Jews. As most of these were working class or poor, they too headed for the laboring quarters.

The Germans, along with Jewish migrants of Polish, Dutch, and English descent, were accustomed to Ashkenazic rites, but the established city Jews who ran Shearith Israel insisted on Sephardic ritual, alienating newcomers. The Mill Street temple was also far away, overcrowded, and required a payment of two shillings (for charity) before one could read from the Torah. In 1825, after protesting the latter practice (at the same time poorer Protestants and Catholics were attacking pew rents), the Ashkenazim split away from the parent body. Forming a new congregation, B’nai Jeshurun, they purchased a church on Elm Street, close to where less affluent Jews had settled, and adopted Ashkenazic ritual. In 1828 another split produced Anshe Chesed; more secessions followed as national groups sought their own synagogues. Finally, in 1833, the old Mill Street synagogue was sold off, and Shearith Israel erected an imposing gas-lit edifice on Crosby Street; its consecration in 1834 was attended by the mayor, several Christian clergymen, and many “of the most distinguished gentlemen of the city.”

In working-class Protestant ranks, the Methodist and Baptist “mechanick preachers” of the turn of the century were followed by revivalists energized by the Second Great Awakening, then rolling into Manhattan from the frontier. Making use of successful camp-meeting techniques, they got urban congregants clapping, jumping, and screaming in holy ecstasy. Those seeking salvation were coaxed from their pews and “called to the altar,” where they were prayed over until the spirit struck. Baptists gathered outdoors at the shoreline point of Corlear’s Hook and performed rites of immersion in the East River. Between 1816 and 1826, at least ten Baptist churches were enlarged, rebuilt, or constructed in working-class wards, and shopfront chapels became a common sight along the Bowery. Though popular evangelicalism would remain predominantly a western and rural phenomenon, by 1825 New York City had nevertheless become one of its three leading centers.

Baptising Scene, lithograph by Endicott and Swett, 1884. Immersions were a common sight along the Hudson as well as the East River. This one took place near the foot of modern Horatio Street in Greenwich Village, just below the White Fort erected during the War of 1812. (I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection. Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

Methodists won working-class male and female converts by offering “free churches” that did not charge pew rents, allowing prayer in mixed-gender assemblies, and teaching that possession of earthly riches did not signify grace and might even suggest sin. On July 4, 1826, at potter’s field, a gardener and lay preacher named David Whitehead invoked divine wrath against the “pretty set” who lived in luxury. Also in the mid-1820s, a group including Sarah Stanford, Baptist and daughter of almshouse chaplain John Stanford, began denouncing elite Presbyterians for their luxurious diets, clothing, and home furnishings.

Not all evangelicals were pleased with this turn of events. Nathan Bangs, “preacher in charge” of the Methodist Circuit of New York City since 1810, believed that the revivals had “degenerated into extravagant excitements.” A severe, self-educated son of a Connecticut blacksmith, Bangs denounced the “impatience of scriptural restraint and moderation, clapping of the hands, screaming, and even jumping, which marred and disgraced the work of God.” Bangs also demolished the old John Street chapel in 1817 and replaced it the following year with a much grander edifice. Gradually he marginalized the more enthusiastic preachers, curtailed the singing of spirituals, and imposed order, efficiency, and method. Bangs’s emphasis on disciplined self-repression appealed to some Methodists, especially second-generation members who sought to combine spiritual salvation with dignified respectability. But others were distressed at Bangs’s restrictions and the imposing new John Street Church. They broke away in 1820, formed their own “Methodist Society,” and erected three more modest structures in the uptown wards.

African Methodists too were roused to new assertiveness. In 1821 Mother Zion broke from its parent body and, with two other black churches, formed its own denomination, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (later the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church). African Zion became the largest black congregation in the city; its recruits included Isabella Van Wagenen, a newly arrived (1828), recently freed, Hudson Valley slave who would later rename herself Sojourner Truth.

Black Episcopalians also established a presence in the Five Points area. Peter Williams Jr., son of the sexton at John Street Methodist, studied for the Episcopal priesthood and in 1818 supervised the emergence of Saint Philip’s Episcopal Church. With encouragement and financial aid from the parent denomination, members of St. Philip’s, some of them skilled mechanics, constructed their own wooden church on Collect Street between Anthony and Leonard, right in the middle of the Fresh Water Pond landfill. In 1820 Williams was ordained a deacon; in 1826, elevated to the priesthood, he became rector.

The spread of piety proved no barrier to a simultaneous expansion of prostitution throughout the city, but especially in working-class districts. Before the war, fee-for-service sex had been largely restricted to the old Holy Ground (just behind St. Paul’s Chapel) and to a few blocks near the East River docks. Here streetwalkers and brothel strumpets made carnal connection with visitors, sailors, shipyard workers, and (according to various complainants) “idle Negroes,” “dissolute persons,” and “droves of youth.” Outside these clearly defined waterfront districts, commercial sex in the early republican city—certainly by European standards—had a decidedly low profile.

In the 1820s, however, the sex trade boomed. Heightened demand came from the surging influx of single young male immigrants, sailors on shore leave, out-of-town businessmen, and the growing numbers of proletarianized journeymen who, facing an uncertain future, postponed marriage until their late twenties.

Heightened supply came from a pool of female migrants, deserted and widowed wives, and the expanding ranks of the working poor. When “respectable” employment garnered women one or two dollars a week and even low-end whoring fetched twenty to thirty dollars, some turned to part-time prostitution to supplement abysmal wages. Others abandoned miserable jobs as servants or seamstresses only when lashed by hard times—“going on the town” temporarily until conditions improved. (Some estimates suggest that perhaps 5 to 10 percent of all women between the ages of fifteen and thirty prostituted themselves at some point, with the figure rising above 10 percent during depressions.) Still others actively embraced the trade on a full-time basis. It paid well, allowed (indeed required) the purchase of fancy clothes, and offered entree into fashionable worlds from which their poverty-scarred mothers were forever barred. All-female brothels, moreover, offered a heady freedom from surveillance by male employers and from subjection to parental authority (or abuse).

The number of brothels in the city rose rapidly in the 1820s. By decade’s end there were probably more than two hundred. Though the docks remained a haven for the coarsest bawdy houses, the riverfronts lost their monopoly on the business. Brothels thrived almost everywhere, their form varying with the local clientele. Elegant and expensive “parlor houses”—so called for their genteel furnishings and fashionably dressed residents—could be found just west of Broadway, a short walk from imposing elite homes, the big hotels, and the theatrical district by City Hall Park. Here native- or New England-born women held sway, many of them well spoken and well educated, some of them accomplished musicians. Parlor house girls could fetch fifty to a hundred dollars a week, working only afternoons and early evenings.

At Corlear’s Hook, adjacent to the shipyards, coal dumps, and ironworks, droves of streetwalkers brazenly solicited industrial workers, sailors, and Brooklyn ferry commuters. So notorious was the Hook’s reputation as a site for prostitution that (according to one theory) the local sex workers were nicknamed “Hookers,” generating a new moniker for the entire trade.

It was the Five Points, however, that emerged as the summit of public sexuality. Prostitutes walked the streets day and night and worked out of saloons and “houses of bad fame” strewn along Anthony Street and the Bowery. Whoring here was famous for its interracial character. African-American New Yorkers, barred from all but service trades, assumed a significant role in the illicit economy. Some of their establishments catered exclusively to other blacks, but numerous Points saloons and brothels accommodated a mixed clientele with a mixed staff. Some haunts featured miscegenational sex; Cow Bay Alley’s black-and-tan cabarets attracted venturesome young gentlemen from the proper west side to what municipal authorities in 1830 called the “hovels of negroes.”

Some madams did extremely well. Maria Williamson, who by 1820 was already running what one contemporary called “one of the greatest Hoar Houses in America,” reinvested her profits in additional brothels and soon owned over half a dozen. But the people who did best in the business were slum landlords. Rentiers delighted in housing madams, who paid hefty rents, and paid them right on time, unlike most tenants in poor neighborhoods, who paid late or not at all.

One of the most enterprising de facto whoremasters was John R. Livingston, brother of Chancellor (and steamboat financier) Robert Livingston. By 1828 he controlled at least five brothels near Paradise Square and a score more elsewhere in the city, with a tenant roster that included some of the best-known madams in New York. His involvement was well known, and when irate neighbors complained, he simply reshuffled the offending women to another of his buildings. Tobacco entrepreneur George Lorillard and Matthew Davis, a founder of Tammany Hall, were also among the ranks of patrician sex profiteers.

Theater owners, including John Jacob Astor (who had purchased the Park back in 1806), encouraged erotic third tiers as drawing cards, providing special entrances from which the femmes dupave could reach the upper house. There assignations were struck and rendezvous arranged at nearby brothels (in the 1820s there were bordellos within easy walking distance of every major theater). Nor were hoteliers (Astor again chief among them) overly chagrined when whorehouses set up shop near their lobbies. The tourist-boosting potential of brothels was one of many reasons they were seldom bothered by the police, nor their landlords punished. Besides, prostitutes who did not solicit openly on the streets violated no law, and few men in positions of power were in any hurry to criminalize their activities. Police did occasionally raid low-life brothels, notorious for robbing patrons, but the arrested women were usually booked on charges of vagrancy or disorderly conduct.

If the sex trades flourished with the not-so-covert acquiescence of the town’s male elite, genteel women upheld strict social sanctions against its female participants, no matter how much money they accumulated. Eliza Bowen Jumel, daughter of a Providence, Rhode Island, prostitute and herself a professional of some standing in her youth, had married French-born wine merchant Stephen Jumel, who in 1810 gave her the old Roger Morris mansion above Harlem. For all her wealth, she was barred from Knickerbocker society. Even after 1826, when she returned from a decade in France, where she’d won social acceptance, she was unable to crack the wall of disapproval and lived in splendid manorial isolation at 160th Street. (She did, however, manage a short-lived marriage in 1833 with the equally notorious Aaron Burr, who had returned to New York eight years after the duel with Hamilton and resumed the practice of law.)

The eruption of commercial sex was accompanied by a surge in commercial drink—again, a phenomenon that suffused New York society but flourished particularly in the laboring quarters. Drinking was a long-established component of male working-class life. On the job, frequent drams fortified tiring workers: shipyard bosses would pass a pail of brandy, then suggest raising another timber. In hot weather, iced beer helped make steamy workshops bearable. Swigging was a preindustrial work habit, to which laborers clung all the more stubbornly in the face of drives for effciency and punctuality launched by employers. Alcohol also lubricated rites of civic and communal solidarity—from militia musters to elections—and bouts of social drinking fueled unofficial holidays, such as boisterous wakes. The first words two just-met strangers might likely utter were “Let’s liquor.”

What changed in this era was the nature and availability of that liquor. After the Revolution, declining West Indian sugar imports, along with duties on rum and molasses, forced importers and distillers to hike prices. Western whiskey filled the breach, as farmers, using improved still technology, sent ever greater quantities of more potent liquor coursing eastward. Rampant overproduction hammered the price down to twenty-five cents a gallon, less per drink than tea or coffee. Urban outlets competed briskly to dispense the cheaper and higher-proof spirits. In 1819 thirteen hundred groceries and 160 taverns were licensed to sell “strong drink,” with the Sixth Ward home to 238 of them. By 1827 there were more than three thousand approved outlets, and on some Five Points blocks over half the houses accommodated a grogshop or grocery. Brooklyn did its best to keep up: in 1821, of the village’s 867 buildings, ninety-six were groceries or taverns.

Taverns were particularly popular with the vast numbers of young men stacked in dreary boardinghouses. Saloons became workingmen’s parlors—places to eat, play, and affirm one’s generosity by treating comrades. Saloons and groceries also served as informal labor exchanges; out-of-state employers set up temporary hiring halls there. In addition, publicans and grocers offered loans and lines of credit, posted bail bond, and provided workers a cushion in difficult times—while further encouraging consumption of booze.

Like commercial sex, commercial drink had powerful patrician supporters, including the city fathers, as a group of outraged petitioners discovered in 1829. Some twenty-four hundred memorialists from outside the Five Points urged the Common Council to tear down a triangle of the section filled with tenants, taverns, and “horrors too awful to mention” and build a new jail on the site. The Street Committee backed the proposal, noting that the buildings in question were “in ruinous Condition” and occupied only by the “most degraded and abandoned of the human species.” Others in government responded that the area produced great income for the Corporation “on account of its being a good location for small retailers of liquor who have located themselves in the vicinity. What may be considered a nuisance,” they concluded, “has in reality increased the value of the property.”

Men played as hard as they drank in the working-class wards. Though official opposition had almost eliminated the baiting of bulls and bears by 1820, cockfighting continued to thrive, as did ratbaiting, a blood sport even more suitably scaled for urban life. Patsy Hearn’s Five Points grogshop, across from the Old Brewery, had a “Men’s Sporting Parlor” famous for its ratfights. Seated on pine planks around a railed-in sunken pit, fifteen feet square, two hundred men at a time watched while an escaped slave named Dusty Dustmoor released packs of rats collected by neighborhood youths. While the rodents engaged in losing combat with trained terriers, spectators wagered furiously on the number of rats the dogs would kill.

Trotting flourished too, as plebeian drivers ran informal matches along Third Avenue from after work to dusk or on Sunday afternoons, after which they repaired with their panting steeds to one of the taverns dotting the high road. Eventually a track for harness racing was built in Harlem, and, in the winter of 1824-5, the New York Trotting Club was formed, dominated by prosperous butchers.

New circus theaters arrived as well. The Lafayette (on Laurens near Canal), the Broadway (in a large wooden building between Canal and Grand), and the Mount Pitt (on Grand Street nearer to Corlear’s Hook) featured dancing girls, equestrian displays and races, and shows by traveling musicians and acrobats.

The most novel development in popular amusements was the transformation of the Bowery itself into a full-blown working-class entertainment strip. On Saturday night, after weekly wages were paid, pleasure seekers headed for its lamp-lit sidewalks. Bowery taverns, brothels, porter houses, oyster houses, dance halls, and gambling dens filled up with sailors, young butchers, day laborers, small employers, journeymen and apprentices from nearby furniture shops and shipyards, and smartly dressed young women as well.

The street’s premier institution was the Bowery Theater. For a few years after it replaced the Bull’s Head Tavern, Ithiel Town’s faux-marble Greek temple had, as planned, attracted genteel patrons. They liked its sumptuous crimson curtains, its gas-illuminated globes (the nation’s first), its boxes painted gold in front and apple blossom in back—a color, the Mirror noted, that showed off the occupants “to best advantage.” And the Bowery charmed the fashionable with fare similar to that offered by its Park and Chatham rivals: Shakespeare, sentimental dramas, farces, French dances, English operas, and Italian singers.

But the Bowery was far bigger than its competitors. It could hold a thousand more spectators than the Park. Usually it didn’t, as patrician fare didn’t lure plebeian audiences. So the management adjusted the entertainment mix to include more spectacular offerings. It ran equestrian events. (One paper noted that though the Bull’s Head had been evicted only recently, “now horses are again prancing where they were formerly.”) Tubes transported water to center stage for aquatic displays. Novelty acts abounded, including one in 1828 during which sixteen Indian warriors did the Pipe Dance on stage. The narrator-chief was shockingly nude from the waist up, but one newspaper assured New Yorkers that the “difference in color removes all the idea of indelicacy, which a similar exposure of white men would occasion.”

Charles Gilfert, the Bowery’s manager, also found that tragedies seldom drew audiences sizable enough to cover the large salaries required to win top actors—already known as “stars”—away from rival theaters. So he turned to melodramas, a recent British import that provided blood-and-thunder action, spectacular mechanical enhancements, and starkly moralistic plots. Melodramatic heroes and villains—their characters written all over their faces—battled to an invariably happy ending, in which the forces of evil were overcome.

The Bowery nurtured America’s first master of the form, the Manhattan-born Shakespearean actor Edwin Forrest. Though he made his debut at the Park in 1826, Gilfert won him away to the Bowery for the next several years. Forrest’s bombastic, muscular style matched the demands of melodrama and the proclivities of the working-class portion of the Bowery’s audience. Their roars of approval lofted him to heights of fame unmatched by any contemporary American actor.

Gilfert tried to keep his elite attendees happy too, with English dramas and English stars, who worked in the British style featured at the Park, but the balancing act proved difficult to sustain. Gilfert died suddenly in 1829 and was succeeded in 1830 by Thomas Hamblin, who wholeheartedly cast his lot with the Anglo- and Irish-American artisans and laborers who peopled the surrounding neighborhoods. The Bowery ostentatiously promoted “native talent,” and its hyperpatriotism, lower prices, stage pyrotechnics, and shrewd choice of plays (Hamblin immediately doubled the number of melodramas) garnered an intensely loyal and vociferous audience of shopkeepers, small masters, wage-earners, and prostitutes. The elite decamped. By the time Mrs. Trollope arrived, it was evident that although the Bowery was “as pretty a theater as I ever entered,” it was decidedly “not the fashion.”

New York’s theaters and working-class communities nurtured into vigorous life a peculiarly American cultural product: the minstrel show, a racially charged entertainment form that would eventually sweep the nation and much of Europe. Minstrelsy had many seedbeds, but one of the most important lay in black Manhattan.

In the summer of 1821 William Henry Brown opened a pleasure garden in his back yard. Brown, a West Indian black, had served as a steward on Liverpool packets before giving up the sea and buying a house at 38 Thomas (between Chapel and Hudson), a street well known for its brothels. Now he dispensed brandy and gin toddies, porter and ale, ice cream and cakes to black patrons, who were barred from the other private gardens in town. The African Grove, as Brown called it, was a smashing success. As the National Advocate noted, “black dandies and dandizettes” gathered in their finest (the men particularly resplendent in their fashionably cut blue coats, cravats, white pantaloons, and shining boots) to saunter and flirt, listen to music from a “big drum and clarionet,” and, occasionally, hear songs sung by James Hewlett, a waiter at the City Hotel.

In the fall of 1821 Brown moved his entertainments inside, a shift hastened by complaints from white neighbors about the noise, and launched his African Theater. Brown offered mostly Shakespeare—Hewlett, who proved a gifted thespian, opened as Richard III—and modern plays as well. As in white theaters, hornpipes were danced and comic songs sung between acts. The African Theater was a great success with black men and women. More remarkable, white patrons began showing up in substantial numbers, allowing Brown to move to a thrice weekly schedule, and he replaced “African” with “American” in the company’s name.

The entrepreneurial Brown decided to expand still further. He rented a house way uptown, on the southeast corner of Mercer and Bleecker, and again whites turned out, especially “laughter loving young clerks,” though some were more interested in heckling than listening. The National Advocate noted in October 1821 (with conventional condescension) that the troupe had “graciously made a partition at the back of their house, for the accommodation of the whites” who, the group’s handbill said, “do not know how to conduct themselves at entertainments for ladies and gentlemen of color.”

Giddy with success, Brown now overreached. He audaciously rented space in a hotel right next door to the Park Theater and put on three performances a week during January 1822. The Park’s manager hated the competition and hired ruffians who cracked jokes, threw crackers onto the stage, and started a riot. The watch responded but, rather than ejecting the provocateurs, arrested the cast, with Hewlett wittily tossing off Shakespearean lines as he was hauled away.

Brown set up shop again at his former quarters, and his patrons, now predominantly white, followed him. For a brief time, audiences could watch the earliest work of one of the era’s great actors, Ira Aldridge, until the teenager’s father, a deacon at Mother Zion, made him quit to pursue a ministerial career. (To no avail: Aldridge, aware he had no chance to develop his talents in race-bound New York, fled to London, where he would play Othello at the Royal Theatre, and become the rage of Europe for a quarter century.)

Brown’s troupe carried on through the summer of 1823, surviving a nasty assault in August 1822, when fifteen members of a nearby circus, camped above Canal Street, attacked the theater, beat Brown severely, stripped the actors and actresses, and demolished the furniture and scenery. Whether the company fell victim to further white violence, a yellow fever epidemic, or limited financial resources is unknown, but Brown closed on a militant note, offering a drama of his own creation, The Drama of King Shotaway, Founded on facts taken from the Insurrection of the Caribs in the Island of St. Vincent.

Apart from a final attempt to establish a black theater later in the 1820s, African Americans would not again stride the boards in New York City for many decades. What replaced genuine black performance was “blackface minstrelsy,” in which white men, painted up as black men, mimicked what they alleged to be Negro culture.

Blackface “masking” had been familiar to colonial Americans, in the form of rioters blacking up to hide their identity and in onstage portrayals of Negroes by Caucasians. But probably the first white person to deliberately appropriate elements of black culture for the purpose of performance was Charles Mathews, an English actor who toured the United States in 1822-23. Mathews, known for his benignly humorous renderings of Scots, Yorkshiremen, and other regional British “types,” quickly added a “Yankee” characterization for local audiences. He also began assembling scraps of song and dialect from black preachers, stagecoach drivers, and the actors at William Brown’s African Theater. From this body of transcribed lore, speeches, and sermons, Mathews built up a “black” characterization, which became a staple of his new act, A Trip to America. Mathews later claimed he’d seen the audience at the African Theater demand that Aldridge, playing Hamlet, stop his soliloquy and sing the popular freedom song “Possum up a Gum Tree.” Aldridge denied Mathews’s story, though claiming not to mind, as Mathews was a fictional humorist. But Mathews’s use of the song appears to be the first certain example of a white borrowing black material for a blackface act.

Others followed Mathews—in 1823 Edwin Forrest took the boards as a plantation black, and in 1828 George Washington Dixon sang “negro melodies” such as “The Coal-Black Rose”—but the man who created blackface minstrelsy was a New Yorker named Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice.

Rice, born in the Seventh Ward in 1808, apprenticed as a woodworker but abandoned the artisanal life for a theatrical one (he was not alone in segueing from a collapsing craft into the flourishing world of commercial culture). Drifting west, Rice worked as a stagehand and bit player throughout the Mississippi Valley. In 1828, according to one version of the story, he came across a crippled old slave named Jim Crow who did an odd shuffling dance. Rice borrowed the man’s style, his persona, even his clothes, and fashioned a song-and-dance routine that became an instant sensation. Dressed in a dilapidated, ill-fitting costume, with patched breeches, a broad-brimmed hat, and holes in his shoes, Rice would roll his body lazily from one side to the other while singing his waggish signature ditty in exaggerated dialect. Audiences used to the high-stepping tapping of Irish jigs thrilled to the black-derived shuffle (ancestor of the soft shoe), in which the feet remained close to the ground and upper-body movements carried the action.

By the late 1820s Rice was serving up his alleged Negro songs and dances as brief burlesques and bits of comic relief in circuses, theaters, museums, and pleasure gardens throughout the West. In November 1832 he brought his routine back home. Spectacularly successful, Rice regularly “jumped Jim Crow” at the Bowery Theater, sandwiched between plays as an entr’acte. In January 1833 he staged a full “Ethiopian Opera”—Long Island Juba, or, Love by the Bushel—featuring a group of “blacks.” And in May 1834 he put his character to topical use as a participant in a play called Life in New York, or, the Major’s Come, in which Rice tunefully discussed a ride in an omnibus, a trip to Harlem, and life in the Five Points.

Guised in blackface, the artist could also safely mock elites, snobs, and condescending moralists. But if Rice’s Ethiopian operas skewered upper-class manners and pretensions, they mainly lampooned blacks. Jim Crow, the slow-witted, irrepressibly comic “plantation darky,” was soon joined by Zip Coon, the second essential stereotype of the nascent minstrel tradition. Where Jim Crow evoked the rural South, Zip Coon, a fancied creature of the urban North, was a foolish, foppish, self-satisfied dandy. An ultramodish dresser, he was given to skintight pantaloons, a lacy jabot, a silk hat, a lorgnon held with effeminate affectation, and his beloved “Long Tail Blue,” an indigo coat with padded shoulders and long swishing tails.

T.D. Rice as Jim Crow, 1833. During Rice’s performances at the Bowery Theater, enthusiastic audiences routinely clambered onto the stage, leaving him little room to perform. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Rice and other minstrels assembled the Zip Coon image from fact and fiction. There were blacks who thrived on imitating (or parodying) white dandies—who enjoyed wearing flamboyant, brightly colored, occasionally mismatched articles of clothing, purchased cheaply in urban markets. White minstrels gained familiarity with black manners, games, and dances in the racially integrated streets, taverns, and brothels of the Five Points or waterfront.

Crow and Coon were paradoxical creations. Their primary import was racist ridicule. Slavery was presented as right and natural; slaves as contented, lazy, and stupid; northern blacks as larcenous, immoral, and ludicrous. At the same time, Rice’s act (like those of his colleagues) was laced with envy. At a time when employers, ministers, and civic authorities were demanding productivity, frugality, and self-discipline, Crow and Coon shamelessly indulged in sensual pleasures. Minstrelsy projected unbuttoned modes of behavior onto “blacks,” allowing spectators to simultaneously condemn and relish them.

Minstrelsy was an exercise in creative cultural amalgamation, something for which New York would become famous. It blended black lore with white humor, black banjo with Irish fiddle, African-based dance with British reels. Rice’s act embraced the promiscuous racial reality of America—nowhere more dramatically evident than in the Five Points—yet it was received with greatest enthusiasm by white Boweryites, who were increasingly concerned to demarcate their culture from that of blacks. By constructing a spurious image of “blackness,” it helped develop a category of “whiteness.” At the Bowery Theater, Anglo- and Irish-Americans, in laughing together at “niggers,” forged a common class identity built on a sense of white supremacy.

Whiteness, however, was far too broad a social category to be serviceable as an everyday identity marker, especially given the diminishing percentage of African Americans in the city. Working-class communities spawned numerous social organizations, keyed to work or neighborhood, within which working-class males gained a sense of participation and belonging.

With bucket brigades obsolete—the department formally abandoned them in 1820—firefighting became ever less a civic enterprise, ever more the private prerogative of the (as of 1825) fifty volunteer fire companies. These groups were changing, getting younger, and drawing in far more journeymen and laborers than masters and merchants. They were evolving into a species of workingmen’s fraternal order, replete with mottoes, ornate insignias, and names that honored heroes and heroines of the republic, the theater, or the turf. After work, mechanics would rendezvous at their engine house, socializing while they polished their elaborately painted machines, or they would repair to the particular bar or oyster house their company had adopted as a haunt. The volunteers developed tremendous esprit de corps and marched together, with their gleaming machines and colorful banners, in every municipal celebration.

Rivalry between these fiercely proud and intensely macho companies led to regular scuffles, ranging from prankish raids on rival firehouses to capture their regalia right on up to battles over who had the rights to a particular fire. At first alarm, some companies would send out an advance guard to put a barrel over the nearest hydrant, sit atop it, and defend it until his comrades arrived. This precipitated fierce fights for possession of the water supply, rather than conjoint concentration on wetting down the flames.

Such combat drew in others. Most fire companies attracted a set of hangers-on, usually boys (over half the school-age population was not in school). The youths were drawn by the excitement and physicality of firefighting: nothing else in urban life could match it. There were also large numbers of men—temporarily or seasonally or permanently unemployed—who enlisted as informal volunteers, helping to drag the engines. In 1824 the Common Council, complaining of the number of boys, idlers, and vagabonds hanging about the firehouses, ordered the companies to dispense with their services, but soon they were back again.

Clusters of young workingmen also formed themselves into gangs. These groups swaggered about the city after work and on Sundays, staking out territories, picking fights, defending the honor of their street or their trade. Butcher’s-boy gangs like the Highbinders were particularly obstreperous, hardened as they were by the bloody work of dispatching cattle, but watermen brawled as well, taking on bookbinders and printers.

Religion too became a rallying ground and point of contention. On July 12, 1824, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, Irish Presbyterian laborers took up fife, drum, and Orange flag and commenced a celebratory parade through Greenwich Village. Awaiting them were a grim assembly of Irish Catholics, mostly weavers, who demanded the Orangemen lower their colors. Someone threw a punch, out came clubs and brickbats, and a furious donnybrook got underway. After countless rioters had fallen, the watch arrived and arrested thirty-three participants, all Catholics.

At the ensuing trial, Emmet and Sampson got their compatriots off by recounting to the judge, Recorder Richard Riker, the long history of Irish mistreatment. Riker responded evenhandedly, chastising the Orangemen for introducing to the United States the “dangerous and unbecoming practices, which had caused so much disorder and misery in their own [country],” and blaming the Catholics for letting themselves be provoked. He then lauded all the combatants as valuable accessions to the nation and urged them to set aside ancient quarrels and forge amicable relationships in their adopted homeland.

Like the Callithumpian bands, bumptious volunteers and fractious gangs, as emblems of disorder, would draw increasing attention from civic authorities concerned over what appeared to be growing numbers of masterless men.