With the guns silenced, New York’s exporters, importers, shippers, and bankers set out to repair their severed southern connections. Cotton might no longer be king, but as the country’s leading export it remained, the Times noted, “a magnate of the very first rank.” To restore the antebellum status quo as quickly as possible, New York businessmen overwhelmingly supported President Andrew Johnson’s policies. They applauded the president’s grant of amnesty to most ex-Confederates, accepted a quick return of southern representatives to Congress, and raised no objections when state legislatures passed “Black Codes” imposing virtual peonage on freed slaves.

Less than a year after the fighting ended, though, leniency had reaped few rewards. When New York City’s Chamber of Commerce commissioned an envoy, Thomas N. Conway, to canvass the old Confederacy for prospects and to let former rebels know that “money in vast quantities was awaiting a chance of safe and profitable investment,” Conway turned in a gloomy assessment. There were, he reported, planters desperate for funds to restart operations, merchants eager to hook up with old trading partners, and would-be southern industrialists who needed northern capital to build railroads, erect textile mills, and exploit mineral resources. But enthusiasm from the few was offset by hatred from the many. There was no way, Conway reported, that New Yorkers “could live and safely conduct business in any section of the South.” Nor were serious profits likely. Whites were obsessed with subordinating the newly freed blacks, and looming racial turmoil would make southern labor unproductive and unreliable.

Conway’s predictions were quickly confirmed. In May 1866 Memphis whites fired and pillaged hundreds of black homes, churches, and schools, gang-raped black women on the streets, and murdered dozens of black men. In July a massacre in New Orleans left thirty-eight dead and 146 wounded. These events shocked and angered many New York businessmen. So did the decision by “reconstructed” states to send Confederate congressmen, Confederate generals—even the Confederacy’s vice-president!—to represent them in Washington. Presidential reconstruction, it seemed, was letting southerners win back politically what they had lost on the battlefield.

These developments strengthened the radical wing of the Republican Party, which had been arguing for much tougher treatment of the South. Freedmen, radicals argued, should be granted political and civil rights, and former Confederate leaders should be disfranchised. The most militant radicals called for expropriating ex-slaveholders’ lands and dividing them up among poor whites and blacks. Radicalism had attracted few New Yorkers outside the Union League Club or the city’s African-American community, but the appalling news out of the South enhanced the appeal of harsher measures.

Riding the surge of resentment, Radical Republicans swept to national triumph in the fall 1866 elections, capturing two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress. In 1867 they imposed military rule on the South. Federal troops oversaw enrollment of voters, this time with blacks included and most Confederate officials excluded. The newly reconstituted state governments ratified the Fourteenth Amendment—a guarantee of equal rights (short of suffrage) for all citizens, to be overseen by the national government—and embarked on social reforms.

Propertied northerners balked at any confiscation of planter lands, however, and by the time the 1868 presidential campaign got under way, New York Republican conservatives believed reconstruction had gone far enough. Democrats believed it had gone too far. Selecting Horatio Seymour, New York’s wartime governor, as their presidential standard-bearer, they denounced Republicans for subjecting the South to rule by “a semi-barbarous race of blacks” who longed to “subject the white women to their unbridled lust.” Conservative Republicans, seeking a candidate who would accept the new status quo but foreswear dramatic new departures, turned to Ulysses S. Grant. Indeed the Grant candidacy was born and bred in New York City, launched by such businessmen as A. T. Stewart, Cornelius Vanderbilt, William B. Astor, and Hamilton Fish. The general lost the metropolis, still stubbornly Democratic, but carried the nation.

Under federal protection, southern governments tried hard to attract northern investment. They extended munificent aid to railroad corporations, exempted new industries from taxes, leased convict labor to entrepreneurs, repealed usury laws, and proved as susceptible as their northern and federal counterparts to being bribed by businessmen. One Georgia legislator got a “loan” of thirty thousand dollars from Harper and Brothers in exchange for a promise to have the new state school system adopt its textbooks.

Yet most New York capitalists shied away from the South. They financed some cotton production (some merchants even acquired their own plantations) and put some money into railroads, the Texas cattle industry, and Florida’s nascent tourist business. Merchants restored the flow of cotton bales through the Hudson River seaport and on to Europe, driving exports from a puny six million pounds in 1865 to over three hundred million pounds by 1873. But with disfranchised, infuriated whites organizing the paramilitary Ku Klux Klan and launching insurrectionary forays against the reconstructed governments, the South seemed “the last region on earth”—as George Templeton Strong formulated dominant opinion—in which “a Northern or European capitalist [would] invest a dollar.”

As their hopes for the former Confederacy withered, New York businessmen grew ever more enthusiastic about the West, eyeing the enormous opportunities opened up by the thrust of railroads across the Mississippi toward California. Before the Civil War only a scant six thousand miles of track had been laid. By 1869 the engineers and work gangs of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific had driven their converging lines toward a golden-spiked conjuncture, and competitors were proliferating rapidly. By 1873 twenty-four thousand miles of track had been laid; by 1877, seventy-nine thousand miles. Railway expansion not only created a truly national marketplace but spurred a cascading industrial development. The demand for rails and railroad bridges galvanized iron manufacturing, summoned the steel industry into being, and touched off mining booms from Pittsburgh to Colorado. These industrial and extractive operations, in turn, attracted vast numbers of immigrant workers, accelerated urban development, and fostered commercial agriculture.

New Yorkers would be deeply involved in the industrialization of the West. The metropolis would finance, promote, and publicize the region’s feverish development, funnel its products to Europe, distribute imported commodities to its populace, serve as portal for the millions rushing westward, and consume vast quantities of its agricultural and industrial products. Soon four of the country’s seven great arteries to the interior (the Erie Canal and the Central, Pennsylvania, and Erie railroads) would be pouring western goods into New York’s harbor—grain, meat, lumber, coal, and iron, both for local consumption and for transshipment to Europe and a growing Latin American market. In return New York merchants would ship westward burgeoning quantities of northeastern industrial products—shoes from Lynn, rifles from Springfield, clothing from Manhattan itself—and the most essential item of all: money.

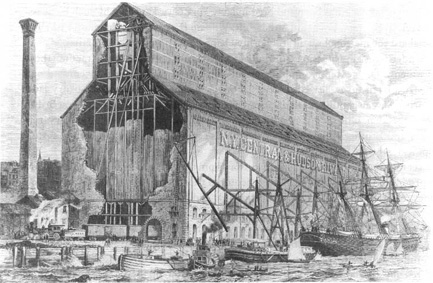

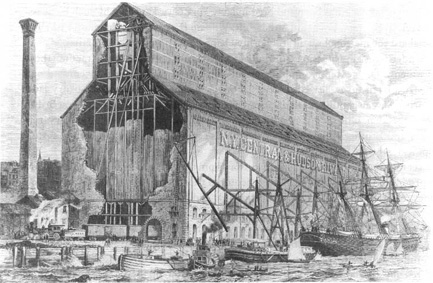

The torrent of western wheat that descended on the city after the Civil War would prompt the New York Central Railroad to erect this enormous grain elevator on the Hudson River at Sixty-First Street in 1879. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Dime novels depicted western settlement as the result of ambitious efforts by innumerable individuals—family farmers and cantankerous cowboys—but pioneering the continent also demanded a far more organized mobilization of resources. Mining, lumbering, steelmaking, railroad building, cattle ranching, and “bonanza” farming were enormously expensive, requiring investment capital on a colossal scale.

Government provided much of the funding (and, of course, the requisite military muscle). No fears of socialism or debilitating dependency hindered entrepreneurs from seeking handouts. Washington and local states gave subsidies, credits, and over a hundred million acres of land to mining companies and railroads, free of charge. The legislative largesse was intended to foster economic development, consolidate the national territory, and, less high-mindedly, to line the pockets of officeholders, as evidenced by the spectacular scandals of the Grant administration.

It also provided a huge windfall for the New York bourgeoisie, who had invested so heavily in such enterprises. Industrialists turned to Manhattan to tap into eastern and European capital pools. Paced by the rapid growth of trading in railroad stocks, Wall Street’s money markets expanded rapidly. By 1868 over three billion dollars’ worth of securities were sold at the New York Stock Exchange, an even larger volume at the Open Board, and still more at the curb. Additional trading at the Gold Exchange, Produce Exchange, and Petroleum Exchange swelled New York’s capital markets until they outranked all their American competitors combined.

Industrialists turned less often now than they had before the war to the city’s merchants, more often to its financiers. Brokerage houses proliferated in downtown Manhattan, especially after the invention of the stock “ticker,” patented in 1867, allowed them to access price information from exchange floors. The crucial financing institutions, however, were the great banking firms, especially those with solid European connections, and the most critical technology was the Atlantic cable, which, restored to life in 1866, made instantaneous communication with overseas investors possible.

Once again foreigners began pouring vast sums into the American economy—the setbacks of 1857, like those of 1837, now merely a hazy memory. In 1853 fifty-two million dollars’ worth of U.S. railroad stocks and bonds had been held outside the country. By 1869 the figure had jumped to $243 million and was accelerating rapidly. Altogether, in that year, Europeans held over $1.46 billion of American securities.

Tremendous power accrued to firms that could raise and funnel funds from Europe into the U.S. economy. Some were old, established operations, like the House of Belmont, with its ties to the House of Rothschild, but new ones emerged as well, the most outstanding being the father-son team of Junius Spencer Morgan and John Pierpont Morgan.

The elder Morgan ran the largest and wealthiest American bank in London. A highly respected firm, it had long specialized in underwriting the sale of British iron to American railroads. But Junius aspired to the loftier plateau of investment banking, where Barings and Rothschilds dwelled. Morgan had developed close ties with leading railroad entrepreneurs (and iron consumers) like Commodore Vanderbilt. When galloping American iron production and steep American tariffs drastically curtailed this trade, Junius shifted easily into underwriting railroad issues.

Like any other European-based concern, J. S. Morgan and Company needed reliable information about the great American West. Junius turned to his son, Pierpont, whom he had long been grooming for the business. After being schooled in Switzerland and Gottingen, Pierpont had started work in a conservative Wall Street firm during the panic year of 1857. Brilliant but rash, the burly young man with the handlebar mustache and intense gaze alarmed his employers, and when they refused to make him a partner Morgan formed his own firm in 1861.

Pierpont composed lengthy letters to his father on America’s political and financial condition (and reported in person to London each spring), but he also found time to participate in the speculative scramble of the war years. (When drafted, he’d purchased a substitute, whom he jocularly referred to as “the other Pierpont Morgan.”) He became a regular denizen of the Gold Room, cleared $160,000 on a market-rigging scam, and financed some speculators who purchased five thousand obsolete rifles from a government armory in New York and resold them to government troops in Missouri at six times the price. Junius, dismayed, orchestrated an alliance with a sober banker thirty years Pierpont’s senior, and Dabney, Morgan, and Company became his New York agent.

As his father moved into railroad financing, Pierpont set out to investigate the frontier first hand. Boarding a train in July 1869—a scant few weeks after the first transcontinental line had gone into operation—he and his new wife, Fanny (daughter of the successful lawyer Charles Tracy), headed for the Far West. After a twelve-day stopover in Chicago, during which he met with officials of the major railroads, he pressed on through Nebraska in one of George Pullman’s recently invented luxury sleeping cars. From his window he spotted Pawnee warriors, wagon trains, and U.S. Cavalry scouts. Then the train notched through the Rockies at South Pass and descended into California, where Morgan spent an additional month, as the guest of prominent Western businessmen, deepening his firsthand knowledge of the emerging American rail system.

In 1871, when Dabney retired, Junius arranged for a new Pierpont partner: Anthony Drexel, a leading Philadelphia banker, who was well aware that the center of financial activities lay in New York City. Two years later, the firm of Drexel, Morgan, and Company moved to a brand-new six-story marbled building on the corner of Wall and Broad streets (the land alone had cost a record-breaking $349 per square foot). The new company, in alliance with Morgan Senior, was perfectly positioned to market railroad and government bonds to English clients and swiftly became one of the leading houses on Wall Street.

England was not the only source of investment capital flowing into New York City. Germany too shipped vast quantities to Wall Street, and this afforded an opening for several German Jewish concerns that had made the transition from commerce to banking. The most influential was the firm of J. and W. Seligman. Joseph Seligman and his brothers, having done well in California commerce, had moved into banking by trading their West Coast bullion on the New York gold market in the 1850s. They quit just in time to keep their fortune from being wiped out by the 1857 panic and bought a clothing factory just in time to take advantage of wartime government contracts. When, to their dismay, they were paid with Union bonds instead of specie, they learned how to convert the paper into hard cash by selling the securities to wealthy contacts in Frankfurt and Amsterdam.

The Seligmans’ expertise caught the eye of the secretary of the treasury, who enlisted their aid in marketing tens of millions of new government notes abroad. It proved much easier to raise money among Germany’s numerous Union sympathizers than in the City of London, whose cotton connections left it cool to the North. When the war was over, the brothers established an international banking house, frankly modeled on the Rothschilds’. Various Seligman brothers were dispatched to Paris, Frankfurt, London, San Francisco, and New Orleans, and in 1869 the House of Seligman became the first German Jewish bank to enter the railway security business.

Close on their heels came another firm that had emerged out of wartime profitmaking. Abraham Kuhn, a German Jewish immigrant, had founded a prosperous drygoods business in Cincinnati. He was joined, after 1848, by a distant relative, Solomon Loeb, son of a Worms wine dealer. During the war they made a fortune providing uniforms and blankets to the Union Army. After Appomattox, they took their capital of half a million dollars to New York City and opened Kuhn, Loeb, a private banking establishment in Nassau Street. Kuhn soon retired to Germany, but the mother country supplied a more than ample replacement when Jacob Schiff, scion of an ancient Frankfurt family of scholars and bankers, joined the firm in 1875.

In the 1870s investment banking firms like Drexel, Morgan, the Houses of Belmont and Seligman, and Kuhn, Loeb constituted New York’s financial elite, partly because they channeled such huge amounts of capital into western industrialization, but also because they were known as ethical operators. Not that they weren’t ruthless businessmen, but they did tend to adhere to a gentlemanly code that emphasized discretion, honest agency, and restraint in competition with one another. These standards worked to their advantage and the city’s: by garnering the trust of distant investors they sustained New York’s reputation as a reliable haven for foreign capital.

Not all New York financiers were honorable men. Ever since the days of Hamilton and Duer, the market had inevitably been a magnet for those who hoped to profit by manipulating the market itself. Prudential investment and speculative rascality were the Castor and Pollux of Wall Street.

The Panic of 1857 wiped out most of the older generation of traders, and the Civil War brought to prominence a breed of brash gamblers, men who played big-stakes games with cutthroat earnestness. In the postwar years, these travelers down Wall Street’s dark side were fortified by an atmosphere of feverish growth, a virtual absence of regulation, and a political system in New York City that facilitated skullduggery.

John Duer’s most notorious incarnations in this era were the improbable trio of Daniel Drew, Jim Fisk, and Jay Gould. Drew, now in his seventies, was one of the few survivors from prewar days, having been a leading Wall Street figure since 1838, when he’d given up driving cattle and turned to manipulating stock. Jim Fisk—tall, florid, and fat—was a vulgarian even by the lights of a gaudy age. With his pomaded and waved light brown hair, his loud suits, his frilled shirtfront garnished with huge diamonds, and his theatrical style, he looked like the huckster he had in fact once been. During the war Fisk wangled contracts to sell dry goods to the government and smuggled cotton through the Union lines. At war’s end he came to New York, bet and blew a fortune speculating on Wall Street, and started anew as a broker handling work for Daniel Drew. He soon demonstrated that behind the genial Falstaffian buffoonery lay a speculative freebooter of the first order.

Jay Gould was not a man who, by his appearance, would shock polite New York (indeed he married into it and set up a model family life on Fifth Avenue). Small, thin, intense, and abstemious, Gould was an enigma, not a peacock, but in his own way quite as amoral as his friend and colleague Fisk. Gould grew up poor and sickly in upstate New York, first visiting New York City in 1853 when he came down to exhibit his grandfather’s better mousetrap at the Crystal Palace. He entered the leather business, moved to New York to deal in the Swamp, then shifted into the stock market as a “guttersnipe,” teaching himself the tricks of an increasingly nasty trade. Learning how to control big enterprises with small holdings, Gould became a consummate litigant and a master of the arts of deception and bribery. He would soon become the most hated man in America.

Cornelius Vanderbilt was no Alexander Hamilton—he had zero qualms about speculative wheeling and dealing—but since he’d shifted from river to rails, by gaining control of the Harlem during the Civil War, he had been a model entrepreneur. Devoting himself to improving the old line’s management and equipment, by 1866 he had turned the Harlem into a going concern, but one whose future profitability, he realized, was imperiled by competition from the Hudson line. Vanderbilt, accordingly, bought control of the Hudson by purchasing its shares on the open market, in partnership with Leonard Jerome and John M. Tobin. Then he coordinated the former rivals’ schedules and rates.

Now it became apparent that the success of his combined operation, which ran to Albany, was at the mercy of yet another road, the New York Central, which controlled the traffic with Buffalo, the junction point with midwestern commerce. Vanderbilt decided to take over the Central too. Buying a minority holding on the open market, he proceeded to convince key Central stockholders—notably John Jacob Astor Jr.—that only by linking up with his roads and letting him manage the conjoint operation would the Central be able to stand up to its competitors for the western trade. By 1867 he had become president and was operating the Hudson and Central as an effective New Yorkto-Buffalo unit.

The roads flourished and paid high dividends. Vanderbilt accordingly issued a vast amount of new stock, nearly doubling the capitalization, arguing that the additional certificates were justified by anticipated earnings. Others had “watered” stock this way, but only to make quick speculative profits; Vanderbilt plowed much of the proceeds back into improvements.

In his new position as commander of the consolidated Central lines, Vanderbilt confronted yet another competitor, the old Erie Rail Road. It too ran from New York City to the Great Lakes. The Erie, moreover, was controlled by his old steamboat rival Daniel Drew, beneath whose pious and austere Methodist exterior beat the heart of a shark. Drew had repeatedly jerked the road’s stock price up or down, as suited his market gambit of the moment, and had launched periodic rate wars to win freight traffic away from the Central.

In 1867 Vanderbilt set out to capture Erie and oust Drew. Drew, seconded by new board members Fisk and Gould, prepared to repel the hostile takeover. The Commodore began by secretly buying up Erie stock, through dummy agents. To block Drew and company from issuing more stock, which would make his buyout harder, Vanderbilt prevailed upon Justice George G. Barnard of the Supreme Court, a Tammany man renowned for his favors to wealthy petitioners, to enjoin Erie from increasing its capitalization. But Drew, Fisk, and Gould evaded the ban and secretly threw millions of dollars of new Erie stock on the market, in effect churning out certificates as fast as Vanderbilt’s unsuspecting brokers could buy them. “If this printing-press don’t break down,” chortled Fisk, “I’ll be damned if I don’t give the old hog all he wants of Erie.”

Vanderbilt soon discovered the ruse but grimly kept buying, driving the price ever higher. Meanwhile, he got Judge Barnard to authorize the arrest of the Erie’s directors for contempt of court. Drew, Fisk, and Gould, one jump ahead of the law, gathered together the company records, baled up over seven million dollars’ worth of greenbacks, and literally decamped with the corporation, fleeing by ferry through the fog to Jersey City. There they set up headquarters at Taylor’s Hotel (promptly dubbed “Fort Taylor”), hired policemen and roughs to protect them from Vanderbilt vengeance, and settled in for a lengthy stay.

The Erie directors now opened up a second front. Their agents in Albany introduced a bill into the state legislature that would, in effect, retroactively legalize all their questionable stock issuances. The proposed bill also shrewdly forbade Vanderbilt from merging the Central and the Erie, on the grounds that it would create a monopoly that would leave the poor and working class vulnerable to price-gouging. While the Erie’s newfound concern for the poor probably changed few votes, legislators did pay close attention to New York City’s merchants, who also feared, and vigorously protested, a Vanderbilt-dominated future.

Winning Chamber of Commerce support gave the triumvirate high hopes for success, but, taking no chances, Gould traveled to Albany, reportedly with a trunk full of thousand-dollar bills, set up shop in the Delavan House, and began buying votes. The Commodore swiftly dispatched counterbribery agents, among them William Tweed, who installed themselves on another floor of the same hostelry. Legislators shuttled back and forth in search of the highest bidder. With the Erie’s treasury close at hand, Gould’s was the more bottomless wallet, and Vanderbilt’s troops deserted him, even Tweed—who was rewarded for his treachery with lavish supplies of Erie stock, netting him $650,000 in all. The desired legislation passed.

Vanderbilt didn’t give up. He met secretly with Drew, who—miserable in New Jersey and ready as ever to sell out his partners—whined his way back into the Commodore’s good graces and initiated a deal. In return for Vanderbilt’s withdrawing his lawsuits and allowing the exiles to come home, Erie would buy back a hefty chunk of his recently purchased stock, even though it would add millions to the company’s debt and leave it virtually bankrupt.

Drew left the road to Gould and Fisk—and two new board appointees, Tweed and his henchman Sweeney—and the duo settled into control of Erie. At Fisk’s urging, they purchased for their headquarters the floundering Pike’s Opera House (at Eighth Avenue and 23rd Street). The top floors became offices; the bottom part—now festooned with frescoes and gilded balustrades—became the Grand Opera House, a theater in which Fisk, wearing his impresario hat, staged extravaganzas. The flamboyance disturbed Gould, who preferred anonymity, but Fisk was in his element. He installed his mistress Josie in a nearby house, and she presided over regular champagne and poker soirees for Boss Tweed, Judge Barnard, and others in what people now called the “Erie Ring.”

Gould proceeded to wring a fortune from the supposedly squeezed-dry railroad by spreading false rumors that sent Erie’s stock quote dancing in the direction he desired. In the course of one audacious scam Gould fleeced his quondam partner Drew so thoroughly that he was forever washed up as a major Wall Street figure. Gould’s gambits, however, deeply disturbed the Erie’s English bondholders, and they asked August Belmont to organize his ouster from the presidency. Gould, in a brilliant maneuver, had the ever complaisant Judge Barnard throw the road into receivership and appoint him its caretaker.

At this point the Erie buccaneers came up against a worthier opponent. Determined to take over a small but strategically located upstate New York railroad, Gould and Fisk began buying its stock on the market. The desperate directors turned for help to Pierpont Morgan. The ensuing contest was a bruiser, the highlight of which was a shootout for control of a railway station in Binghamton. Fisk recruited a small army of eight hundred gang members from the Five Points; Morgan countered with recruits from the Bowery; and in the ensuing free-for-all, at least eight men were shot before the state militia intervened. Morgan’s forces triumphed, and Fisk returned to New York, famously remarking that “nothing is lost save honor.”

Morgan solidified his clients’ position by arranging for a friendly merger with a larger company, then sought and obtained a seat on the board of directors of the consolidated company. It was Morgan’s first such position, and it marked the beginning of a portentous new relationship between financiers and industrialists.

Gould’s railroad predations had seriously annoyed conservative bankers like Morgan, but his next venture, an audacious foray into high finance, horrified and enraged them. In 1869 Jay Gould set out to corner the nation’s gold supply. Given the centralization of finances in lower Manhattan, this was not an impossible dream. The supply of gold in the city was less than twenty million dollars’ worth, and it could all be purchased on credit. Once he had it in his hands, Gould could drive the price sky high. City merchants who needed the metal for their international dealings, and bearish speculators who had foolishly promised to sell gold at a lower figure, would be at his mercy.

The treasury could easily break such a corner by selling some of its vast holdings in the market, instantly driving the price down. Gould, to prevent the newly installed Grant administration from intervening against him, convinced the president that a corner was in the national (and Republican Party’s) interest. If the price of gold went up, American farmers could more easily sell their wheat abroad; railroads would profit from the increased grain shipments; and farmers and railroads were key Republican constituencies. Q.E.D.

Grant agreed, and with the president on board, Gould and Fisk began buying gold. As their army of brokers drove the price steadily higher, howls of outrage reached the White House. Sensing impending doom, Gould began secretly selling gold, even while encouraging Fisk to keep buying and bulling its price. Bears, facing utter disaster, pleaded with the government to sell gold. On September 24, 1869, soon to remembered as Black Friday, crowds of businessmen and merchants facing ruin jammed New Street. As Fisk bought and Gould secretly sold, gold inched up, accompanied by shrieks from the bears, to 145, 150,155. Then, at noon, with brokers crumpling, transactions flying, and the crowd outside so enraged the militia was ordered into readiness, the government dumped gold on the market, sending the price plummeting. Slipping away from the chaos, Gould and Fisk holed up in their heavily defended Opera House headquarters while the reverberations rocked the city.

Scores of smaller dealers failed, one broker shot himself to death, and the market collapsed, threatening a full-scale panic. “Over the pallid faces of some men stole a deadly hue,” wrote the Herald, “and almost transfixed to the earth, they gazed on vacancy. Others rushed like wildfire through the streets, hatless and caring little about stumbling against their fellows.” One man who kept his head was Jim Fisk, who escaped ruin by the simple expedient of repudiating all his contracts and hiding behind Tammany-supplied judges.

Gould kept his head too but lost what was left of his reputation. The collapse of the Gold Corner didn’t precipitate a full-scale depression, but hundreds of businesses failed, and thousands of workers were laid off. They would remember Jay Gould, and the emerging national labor movement would be indelibly affected by this encounter with finance capitalism run amuck. Nor was the press pleased with the turmoil. The Times led a journalistic assault that fastened to Gould forever the character of a sinister and poisonous predator. New York City’s reputation suffered as well. Wartime gambling in the Gold Room had cast the metropolis in a baleful light; Gould’s escapade further blackened its image.

But the men most alienated by the mess Gould had made of the financial markets were the elite directors of conservative banking houses, particularly J. P. Morgan. Gould’s machinations distressed Pierpont both as a matter of business aesthetics and personal interest—his own firm of Dabney, Morgan, and Company was bruised by Black Friday—and in years to come he would dedicate himself to imposing his particular brand of order on the national economy.

From the West’s perspective, the differences between Wall Streeters were less compelling than their similarities, given that most bankers and merchants were determined to restore “hard money.” During the Civil War, the government had churned out greenbacks—paper money not exchangeable for gold—in such massive quantities that the postbellum era inherited an inflated currency. This distressed the banking community, which had never liked greenbacks, finding them all too vulnerable to politicians with printing presses. Merchants hated them, for though legal tender in America they were non grata in Europe and ensnared international traders in endless difficulties.

Seeking a quick return to the gold standard, New York City’s bankers and merchants hailed a Johnson administration plan to make greenbacks “as good as gold” by withdrawing them from circulation and literally burning them up. Eventually, with scarcity, their value would swell to market equivalence with precious metal, and gold and paper could once again be made interconvertible.

Western farmers and businessmen loathed the idea. With their capital-starved region in the midst of a gigantic expansion, there was not enough currency in circulation as it was. They protested a policy that would drive them into deeper dependency on Wall Street. Entrepreneurs in the iron and steel industry—who had done quite well under wartime inflation—denounced this plot by “money lenders” to throttle “productive capital.” Eastern manufacturers agreed. They organized the American Industrial League (1867), installed Peter Cooper as its first president, and complained that contraction would choke the economy into depression.

Western fury at Wall Street was intensified by the perceived inequities of the banking system. Congress had authorized nationally chartered institutions to issue banknotes that could circulate as money but allocated this credit-creating right on a regional basis, giving by far the bulk of it to New York and New England. By 1866 the per capita circulation of banknotes in New York was $33.30; in the Midwest, $6.36; in Arkansas, fourteen cents. This too forced West and South to turn east to finance their own expansion.

The new national financial system had further exacerbated regional inequalities by creating a three-tiered pyramid of banks. At the bottom were “Country Banks,” required for safety’s sake to keep a portion of their capital in a bank located in one of seventeen “Reserve Cities.” These institutions, in turn, were mandated to keep half of their required reserves at a bank in the “Central Reserve City”—i.e., Manhattan. This generated additional outcries against “the money power” that was being “centralized in New York.”

Westerners were even more unhappy with the government’s solution to the bond problem. During the war, Washington had been forced to offer high rates of interest, payable in gold, to those who purchased bonds. By 1869 there were over $1.6 billion of these in circulation. The government now announced that it would pay off the principal in gold too, even though most bonds had been purchased with greenbacks worth fifty to sixty cents at best. This would give bondholders a tremendous windfall profit (akin to that received by New York speculators in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War). Westerners denounced the plan, noting that the great bulk of notes were held by wealthy individuals and financial institutions. One protest pamphlet depicted a sybaritic “Mr. Bond” sitting in his parlor, smoking imported Havanas, downing French champagne, and gloating over tax-free bonds that brought in 11 percent a year, while out west, a disabled union veteran groaned under the high taxes imposed to pay off the corpulent Mr. Bond.

In 1867 Western animosity crystallized around a “soft money” proposal to pay off the bonds in greenbacks, the same depreciated currency with which they had been purchased. “Hard money” forces—centered in New York City—went wild. Academic economists weighed in with treatises about the immutable laws of classical economics. Ministers like Henry Ward Beecher preached sermons on the sanctity of specie and the wickedness of paper money. (Beecher’s text: “Thou shalt not steal.”)

The money issue became central to the 1868 presidential campaign. The Democratic Party held its national convention in New York, the first in the city’s history. A bruising battle pitted a strong western contingent backing paper, against eastern Democrats led by national chairman August Belmont, Samuel J. Tilden, and Horatio Seymour (all intimately tied to Wall Street financial circles), who insisted on government’s moral obligation to redeem in gold. In the end, Seymour got the nomination, only to lose to Grant and the Republicans, who had more decisively declared themselves for hard and moral money. Their word proved to be their bond. On taking office, Republicans immediately passed the Public Credit Act (in March 1869), which pledged to redeem bonds in coin and to make greenbacks as good as gold, as soon as possible.

To raise the massive supply of specie required for a return to the gold standard, the government planned to sell $1.4 billion worth of federal bonds, the largest securities transaction of the decade. For help, the government turned to a syndicate dominated by New York’s international bankers, including the Seligman Brothers (who had close ties to Grant and strong connections abroad), August Belmont and Company (acting on behalf of the English Rothschilds), and Drexel, Morgan (representing Junius Spencer Morgan of London). Syndicate members succeeded brilliantly, accruing hefty profits in the process, and on January 2, 1879, the country went back on the gold standard, a Wall Street triumph bitterly resented in the West.