Since the war, New York’s elite had been spellbound by Paris, glittering capital of Napoleon III’s Second Empire. Shedding centuries of anglophilia, they had passionately pursued all things French, from apartment houses to mansard roofs, from boulevards to ball gowns, from the cancan to the Crédit Mobilier. Now, in the summer of 1870, they were riveted by the rise and fall of the Paris Commune.

Bismarck’s rising empire had declared war on France, crushed Napoleon’s troops, and captured the emperor himself. (In Kleindeutschland enthusiasm for Prussian victories reached delirious levels.) Napoleon and Eugenie’s empire reeled, then toppled. The mass of Parisians demanded a republic that would fight on. They got a provisional government, led by haut bourgeois republicans, that only reluctantly prosecuted the war. The Prussians laid siege to Paris and, over the ensuing bitter winter, starved and froze it into submission. In January 1871 the provisional government agreed to an armistice and gave way to a new government, chosen by rural Frenchmen, dominated by landed gentry and royalists and headed by Adolphe Thiers, who accepted a humiliating surrender. But when Thiers’s troops tried to disarm the Parisian national guard, they failed, and he and his government fled the city.

Power passed to the Commune of Paris. Its officials were primarily professionals; its chief supporters craftsmen, laborers, and poor women, who were particularly active in street demonstrations. Within days Thiers’s army launched a second siege of Paris. In May, after bombarding the city’s fortifications, his troops entered the city and attacked the barricades the people of Paris had erected around their quartiers and arrondissements. In the next gruesome week of street fighting, Thiers’s forces made free use of incendiary shells, and the Communards burned great swatches of the city to slow the advancing troops. At the climax, vengeful troops slaughtered thousands of Parisians out of hand, and maddened and despairing Communards shot those they had held as hostages—including the archbishop of Paris—and torched hated public buildings. The victors, urged on by a frightened and frenzied bourgeois press, launched a “Communard hunt,” assembling new-made corpses in great piles at which wealthy women gleefully poked with parasols. “Trials” found thirteen thousand guilty and meted out sentences of death, imprisonment, forced labor, and deportation. Final body count: seventy hostages, 877 soldiers, and over twenty-five thousand Parisians.

New York radicals supported the Parisians. The American sections of the International expressed sympathy for the fight against the Thiers government, and Victoria Woodhull led a dramatic march in memory of the Commune. Exiles who escaped the carnage were welcomed and organized into a French section of the IWA. German socialists too supported the Commune, at the cost of much of their popularity in pro-Bismarck Kleindeustchland. The labor movement’s Workingman’s Advocate printed Marx’s blistering defense of the Commune, The Civil War in France.

Wealthy New Yorkers, however, were horrified by the red flags, the socialist speeches, the carnage of Bloody Week. Many hailed the violent suppression; George Templeton Strong professed delight that the “foot of the bourgeoisie is on the neck of the dreaded and hated Rouges at last,” rendering them powerless, “if anything short of extermination” could do so.

Equally horrifying was the thought that such scenes might be reenacted in New York. Godkin’s Nation saw the socialist specter “gaining among the working-classes all over the world” and declared one had to be “wilfully blind” to “imagine that America is going to escape the convulsion.” Charles Loring Brace insisted that “there are just the same explosive social elements beneath the surface of New York as of Paris,” and the Times concurred. The “terrible proletaire class” had already shown its revolutionary head during the draft riots, the Times recalled, when for a few days in 1863, “New York seemed like Paris, under the Reds in 1870.” Now matters were arguably worse, as there were “communist leaders and ‘philosophers’ and reformers” in New York, ready to stir up the “seething, ignorant, passionate, half-criminal class” who “hate and envy the rich.” Should “some such opportunity occur as was present in Paris,” we should soon see “a sudden storm of communistic revolutions even in New York such as would astonish all who do not know these classes.”

In early July 1871 a group of Protestant Irish-Americans—the Loyal Order of Orange—requested police permission to march through the city streets to celebrate the Battle of the Boyne. Irish Catholic organizations protested that the parade would be an insult to their community and pointed to the Orangemen’s behavior the previous July 12, when they had marched up Eighth Avenue to Elm Park on 92nd Street. As they went they had taunted residents of Hell’s Kitchen, Irish Catholic laborers laying pipelines in 59th Street, and others who were broadening the boulevard farther uptown. They’d spewed epithets and sung insulting tunes, such as “Croppies, Lie Down,” whose refrain ended: “Our foot on the neck of the Croppy we’ll keep.” A crowd of enraged workmen followed along and attacked the Elm Park picnickers with stones and clubs. Shots were exchanged, and eight people were killed.

Such disgraceful scenes, the Catholics argued, must not be repeated. The Orangemen sought “race ascendancy,” argued Patrick Ford, Galway-born editor of the recently established Irish World. They hoped, in league with the nativist “Anglo-American element,” to make the United States a thoroughly “Saxon” nation. But the United States, Ford argued, articulating what would emerge as a major strand of metropolitan thought and feeling, was in fact a multicultured construction—“a political, not a natural, nation.” “This people are not one,” Ford insisted. “In blood, in religion, in traditions, in social and domestic habits, they are many.” It was wrong, therefore, to ask non-English residents to “ignore their own identity and origin” and “become Yankees first, before they can be regarded as Americans.”

City authorities agreed, noting that the use of abusive language or gesture in public streets was a misdemeanor and that courts had declared no organization had the right to provoke violence by inflaming the passions of other groups. On July 10, with Tweed’s backing, Police Superintendent James J. Kelso forbade the parade. Irish organizations and Archbishop John McCloskey (who had succeeded John Hughes on his death in 1864) applauded the decision.

Now Protestants protested. The next day, indignant Wall Street businessmen lined up outside the Produce Exchange to sign a petition denouncing the edict. Leading newspapers raged at the cowardly surrender to a Catholic mob and demanded an instant reversal. Protestant New Yorkers viewed the parade issue through the prism of events in France. Thus the Herald argued that Irish Catholic outcries against Orangemen manifested “the same spirit which prompted the Paris Commune.”

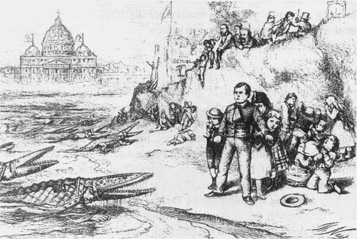

Protestants also feared that Catholic political power menaced republican liberties, an old worry recently revived by Pope Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors (1864), eighty in all, that condemned such tendencies of the bourgeois era as naturalism, rationalism, separation of church and state, liberty of conscience, and (error number eighty) the notion that “the Roman Pontiff can and ought to reconcile himself and come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.” The Times suggested that Catholics intended to set up a state church and drive Protestants “to take shelter in holes and corners,” and Thomas Nast, cartoonist for Harper’s, fashioned images of mitred crocodiles slithering up on the beaches of America.

“The American River Ganges: The Priests and the Children,” by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, September 30, 1871. (General Research. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

These anxieties had been boosted by Tammanyite Mayor Abraham Oakey Hall, who had taken to reviewing the St. Patrick’s Day parade in full Irish regalia, showing up at balls in bottle-green flytail coats and emerald silk shirts, and jocularly claiming his initials really stood for “Ancient Order of Hibernians.” Tweed and company had, moreover, authorized state and city aid to parochial schools and Catholic private charities: the Church got nearly $1,500,000 from public sources between 1869 and 1871. To the Tribune it seemed quite apparent that the Irish, “under the leadership of Mr. William M. Tweed, had taken possession of this City and State.” Superintendent Kelso’s order banning the Orange Parade seemed brutal confirmation of this.

Protestants also fought the banning order because it gave comfort to Irish nationalists, Fenians chief among them. After the war, the Fenians had come up from underground, declared themselves a sovereign government-in-exile, and hoisted their harp-and-sunburst flag over the old Moffat mansion (opposite Union Square), now their capitol. A faction led by William R. Roberts, a wealthy New York dry-goods merchant, pushed to capture British Canada and hold it hostage for Irish independence. This would hopefully embroil the United States in an Anglo-American war, during which Ireland could break for freedom.

This program roused tremendous enthusiasm among New York’s working-class Irish. In March 1866 over a hundred thousand turned out for a Fenian rally in Jones’ Woods—despite the opposition of Archbishop McCloskey. The savings of domestics and longshoremen (not, for the most part, the more conservative Irish middle classes) helped purchase a cache of arms from the U.S. government. But money, enthusiasm, and some tacit support from American officials still fuming at England’s Confederate leanings were no substitute for military competence, and the Fenian invasion forces were easily routed by Canadian militiamen.

This invasion fiasco stimulated the growth of the Clan na Gael (founded 1867), a far more disciplined and secretive organization. Because Irish nationalists retained broad popular support, they were vigorously wooed by Tammany politicians, and Grant Republicans gave them federal jobs in New York City. But leading Irish exiles aligned themselves with the International, which strongly supported Irish independence. Ford of the Irish World linked the nationalist cause to radical enthusiasms by denouncing the “money interest” as “a huge boa constrictor” that “has wound itself about the nation, crushing its bones and sucking the life blood from its heart.”

This combination of concerns about Commune-style radicalism, Irish Catholicism’s growing power in the city, and the emergence of left-leaning Irish nationalism generated intense elite pressure on Tammany to reverse its stand and let the Orangemen parade. Tweed, already feeling the heat from some initial exposés of Tammany corruption, decided he had no choice but to acquiesce. Governor Hoffman came down from Albany on the eleventh and, after conferring with Tweed and Hall, rescinded Kelso’s decision. He also ordered regiments of National Guardsmen and cavalry to guard the marchers the following day.

July 12 dawned bright and hot. Five thousand troops reported to their armories at seven A.M. Some were old hands at this kind of thing—notably the elite Seventh Regiment. At the other extreme was the new-minted Ninth Regiment, a Jim Fisk creation. The master of Erie had bankrolled the troop but put far more energy into its scarlet-coated hundred-piece band than into imparting military discipline. Most Guardsmen were Protestant employees of the city’s financial and business firms (the Irish Sixty-ninth would be kept in its armory all day). Most shared their employers’ fear or hatred of the tenement house denizens whose paths they would cross that day. In addition to the military, fifteen hundred policemen gathered at headquarters in Mulberry Street.

Catholic forces readied themselves as well. For a week there had been vigorous debates in nationalist circles about how to respond should a parade go forward. Ancient Order of Hibernians lodges around New York and Brooklyn had called for violent resistance. Some had undergone street drills in preparation. Fenian leaders were in unusual agreement with the Catholic hierarchy that violence would only make the Irish appear incapable of self-government, but neither priests nor moderate nationalists had much influence that morning.

From all over the city groups of people made their way toward Lamartine Hall, on the northwest corner of Eighth Avenue and 29th Street, where the Orangemen were forming up their tiny contingent. The Green forces came from scattered worksites: longshoremen from East River docks, laborers from the Jackson and Badgers Foundry on 14th Street, plasterers, Boulevard workers, quarrymen at Mount Morris, Central Park laborers, men doing repairs on the Third Avenue Railroad or digging sewers in Fourth Avenue or manning the Harlem Gas Works. They came from a morning mass meeting at Hibernian Hall—Ancient Order of Hibernians headquarters, at Prince and Mulberry—where there had already been a violent clash with the Eighty-fourth Regiment and the police (except for two “copps” who had refused to fight fellow Irishmen and been promptly fired and jailed). And, of course, they came from the working-class quarters, from Mackerelville (around 13th Street between First Avenue and Avenue A), from Yorkville, from Brooklyn, and—in greatest numbers—from Hell’s Kitchen.

By 1:30 crowds lined both sides of Eighth Avenue, from 21st to 33rd, and jammed the cross streets. Most were laborers, wearing the long black coats and dirty white shirts of their calling. Many neighborhood women mingled in the crowd, and others took up positions at windows and on roofs (reminding one reporter of “the Paris pétroleuse”).

Now the troops and police arrived and took up their positions, to jeers and hisses. At two o’clock, the Orange women and children were sent off, and the men donned their regalia (often with pistols under their coats) and formed up in 29th Street. The men of the Eighty-fourth Regiment, to make clear their unabashed sympathy with the marchers, placed their caps on their bayonets and cheered. The Orangemen were now surrounded by regimental units—the Seventh in front, Sixth and Ninth in rear, Twenty-second and Eighty-fourth to the sides. After some preliminary street clearing by mounted and club-wielding police, a cannon was fired, the band played “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the Orangemen unfurled their purple silk banner of the Prince Glorious on horseback, and the parade set off.

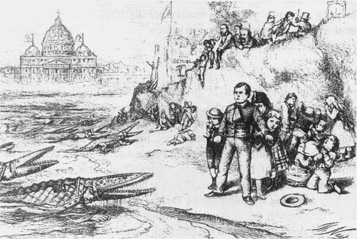

Almost immediately, to howls of “Give them hell, the infernal Englishmen!” a shower of stones, bricks, bottles, and old shoes was unleashed. Some militiamen fired musket shots, pistols were fired from the crowd, police charged and clubbed the bystanders, and the parade moved ahead. A block further on came more stones and sniper fire; Seventh Regiment soldiers responded, on command, with sporadic shots. Eighth Avenue ahead of the line of march grew choked with crowds. The procession halted. One woman broke through the troops and tore the regalia off an Orangeman before being pushed back at bayonet point, shrieking and raging. The police smashed into the crowd ahead, bashing heads open. Stones and crockery rained down from rooftops and windows. More gunshots rang out. Two Eighty-fourth Guardsmen were hit. The troops, without orders and without warning, began blasting volleys at pointblank range into the throngs along the sidewalk at 24th Street. Other regiments began firing indiscriminately into the screaming and terrified crowds. Mounted police followed up with charges.

“The Orange Riot of July 12th,” from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 29, 1871. This view shows the soldiers firing into protesters massed on the east side of Eighth Avenue near 24th Street. (Courtesy of American Social History Project. Graduate School and University Center. City University of New York)

The parade re-formed ranks. The band struck up a festive Orange tune, banners were lifted aloft, and the assemblage ground on. The police had to batter their way into 23rd Street, where immense numbers had regrouped at Booth’s Theater, but the parade successfully negotiated the left turn and headed east, its rear protected from angry crowds, until it reached Fifth Avenue, where, for a moment, it entered a different world: at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, two to three thousand well-dressed people cheered lustily. Further ovations greeted them as they made their way south along Fifth Avenue. Then marchers and troops and police entered Rialto territory at 14th Street. Once again they had to wade through hissing and jeering crowds (except for Protestant oases like the American Bible Society building, from which girls merrily waved orange ribbons). Wearily they made their way across town toward Cooper Union, where finally, at four o’clock, they shed their regalia and quietly dispersed.

Back at Eighth Avenue it was quiet too, apart from the groans of the injured and dying and the lamentations of priests and women. A shaken Herald correspondent found the steps of a basement barbershop “were smeared and slippery with human blood and brains while the landing beneath was covered two inches deep with clotted gore, pieces of brain, and the half digested contents of a human stomach and intestines.” The walls of a butter store, he observed, were “speckled with bullet marks and splashed with blood,” and the sidewalk in front was “thickly coated with a red mud.”

Over sixty civilians were killed outright or later died from wounds. Over one hundred were wounded (and another hundred arrested). Most were Irish laborers, but there were many German and American casualties. Twenty-odd policemen were injured by stones, clubs, and rocks, and four were shot, none fatally. Three Guardsmen were killed (possibly by wild firing from other troops) and twenty-two injured. One Orangeman was wounded.

The next day twenty thousand Irish mourners converged on Bellevue’s morgue, adjacent to the outpatient dispensary for the poor, to pay respects. Massive funeral processions, composed of somber delegations from the Society of the Immaculate Conception, St. Patrick’s Mutual Alliance, and the Ancient Order of Hibernians in white mourning scarves, traveled by the Greenpoint ferry to Brooklyn’s Calvary Cemetery. There were other, angrier responses to what Ford’s Irish World called the “Slaughter on Eighth Avenue.” The Brooklyn Irish hanged Governor Hoffman in effigy in a parade down Hamilton Avenue, and barroom poets composed ballads like “The Great Orange Massacre.” There were, however, prominent nationalists—Fenians and Irish Brigade Association leaders from the ranks of business and the professional classes—who distanced themselves from the whole affair, a sign of divisions to come.

The day after the riot, fashionable men and women rode along Eighth Avenue in comfortable carriages, matching up street corners or buildings with descriptions in the morning papers. But the forces of order, while triumphant, were also in a fury. One banker declared that the riot eclipsed “the worst religious outrage of the Commune.” A Times editor found it final proof that the “Dangerous Classes” cared nothing for “our liberty or civilization” other than to “come forth in the darkness and in times of disturbance, to plunder and prey on the good things which surround them.” Police Commissioner (and banker) Henry Smith only regretted “that there were not a larger number killed.” As he explained to the Tribune, “in any large city such a lesson was needed every few years. Had one thousand of the rioters been killed, it would have had the effect of completely cowing the remainder.”

Democratic authorities got no points for having ordered out the troops. Their “criminal weakness and vacillation,” the Tribune charged, had encouraged the mob in the first place. One of the reasons many in the upper and middle classes had grudgingly acquiesced in Tammany’s hold on power was its presumed ability to maintain political stability. That saving grace was gone: Tweed could not keep the Irish in line. The time had come, said Congregational minister Merrill Richardson from the pulpit of his fashionable Madison Avenue church, to take back New York City, for if “the higher classes will not govern, the lower classes mil.”

Six months earlier, Tweed had seemed impregnable, despite assaults by the New York Times and the vitriolic Harper’s Weekly cartoons of Thomas Nast, which portrayed Tweed as a leering hulk of corruption and Tammany’s inner circle as a conspiratorial Ring. The campaign, long on invective, was short on facts, and the Times insisted the city’s books be examined. Just before the election, Mayor Hall established a blue ribbon panel of six businessmen with unimpeachable reputations—including rentier John Jacob Astor, banker Moses Taylor, and Marshall O. Roberts of the West Side Association—and gave them access to municipal accounts. On election eve, the panel issued its findings. The books had been “faithfully kept,” avowed these leading beneficiaries of Tweed’s policies, and the debt levels were manageable. Tweed and his men swept to victory.

Accordingly, 1871 had looked to be a very good year. On New Year’s Day, A. Oakey Hall was again sworn in as mayor, and John T. Hoffman took office as governor. With luck, by 1872, Hoffman would be president, Hall would move up to governor, and Tweed would become a United States senator. The annual Americus Club Ball, held in early January at Indian Harbor, Connecticut (near Tweed’s summer place at Greenwich), was a jubilant affair. As late as May, Tweed was still riding high. On May 31 he arranged a spectacular wedding, at Trinity Chapel, for his daughter Mary Amelia. At the Delmonico’s-catered reception that followed at Tweed’s Fifth Avenue (and 43rd Street) mansion, guests brought a vast outpouring of dazzling gifts (including forty sets of sterling silver). Tammany’s growth-oriented coalition, like the Gilded Age boom itself, was in fine fettle.

Within weeks, however, the visceral response to the Commune and the Orange Riot had rallied support for the war the Times and Harper’s were waging against Tweedite corruption. On July 22, ten days after the Boyne Day battle, the Times began publishing solid evidence of Ring rascality, turned over to the paper by an aggrieved insider. Day after day, publisher George Jones reproduced whole pages from the cooked account books of James Watson, who until his recent death in a sleighing accident up in Harlem Lane had been the Ring’s trusted bookkeeper. The series culminated in a special four-page supplement, on July 29, that quickly sold out its run of two hundred thousand copies. Under screaming headlines—“Gigantic Frauds of the Ring Exposed”—the paper detailed Watson’s system of kickbacks. Contractors on public projects padded their bills and slipped the overcharge back under the table. The surcharge to the city usually ranged from 10 to 85 percent, though on occasions it soared to truly empyrean heights of corruption. One member of a Tweed-affiliated club was paid $23,553.51 for furnishing thirty-six awnings, boosting the per-awning price from the market rate of $12.50 to a Ring rate of $654.26. Construction of the county courthouse allowed for an orgy of such creative accounting, and the building wound up costing four times as much as the Houses of Parliament and twice the price of Alaska.

The Times stories brought to a head a growing international crisis of confidence in New York City’s ability to pay its debts. Earlier in the year, rumors of mismanagement had so undermined trust that only the unimpeachable credentials of the city’s underwriters were keeping New York’s securities afloat. Now overseas bankers refused to extend further credit. The Berlin stock exchange struck the city’s bonds from its official list.

This jolted New York’s financial and mercantile community into action. Mammoth interest payments on outstanding debt were due in weeks, and in a few months twenty-five million dollars’ worth of short-term notes would come due for payment. If the city’s credit collapsed, noted Henry Clews, a leading private banker, every bank in New York might go down with it. It was time, Qews said, to oust “this brazen band of plunderers, root and branch.”

On a Monday evening in early September, after the elite had returned from their summer vacations, a great reform meeting was held at Cooper Union. In attendance, besides Republicans, nativists, civil service reformers, and frightened financiers, were powerful upper-class Democrats, like corporate lawyer Samuel J. Tilden, who had been forced to take a back seat to Tweed; Germans, led by Staats-Zeitung editor Oswald Ottendorfer, who had felt pushed aside by the Irish; and those small property owners, merchants, and manufacturers who feared Tammany corruption would hike taxes and pauperize them.

The meeting quickly agreed that the “wisest and best citizens” should take control of the city government—as intellectuals and reform groups had been arguing since the draft riots. Extremists, Godkin of the Nation among them, talked cholerically of forming a Vigilance Committee to lynch Tweed. Cooler heads established instead an Executive Committee of Citizens and Taxpayers for Financial Reform of the City, popularly known as the Committee of Seventy. Chaired by sugar refiner William Havemeyer, and packed with Bar Association lawyers, it decided to bring Tweed down by choking off the city’s funds. Setting up offices in the Brown Brothers building—making the banking house de facto center of city government—the committee spearheaded a concerted refusal by a thousand property owners to pay municipal taxes until the books of the city were audited. On September 7 they went before Judge Barnard, who now deserted his former comrades and gave them an injunction that barred Comptroller Connolly from issuing new bonds or spending any money. As Tweed later noted, this “destroyed all our power to raise money from the banks or elsewhere and left us trapped.” Crowds of workmen now gathered at City Hall demanding their pay—a crisis relieved only temporarily by Tweed’s handing out fifty thousand dollars from his own pocket. Organized labor turned against him too, even those in the construction trades who had benefited mightily from his programs. On Wednesday, September 13, eight thousand workmen marched in the rain to City Hall to denounce Tammany rule.

Five days later, Comptroller Connolly jumped ship. At Committee of Seventy insistence, he appointed Tilden associate Andrew Haswell Green as acting comptroller. Escorted by a hollow square of mounted policemen, Green took possession of the office, giving investigators access to Ring financial records and further isolating Tweed. (Barnard allowed the city to borrow from the banks again, but only departments not under Tweed’s control.) At the end of October Green and Tilden traced money from city contractors directly to Tweed’s bank account, and the following day Tweed was arrested, though immediately released on a million dollars bail.

Tweed appealed to the ballot box and held rallies on the Lower East Side, to no avail. In the November 1871 elections—with the polls closely guarded—Tweed retained his state senate seat (and he would remain a Robin Hood hero, “poverty’s best screen,” to his local constituents), but most of his associates were defeated by wide margins. Ring members large and small slipped out of the city for foreign climes. Tweed stood his ground. Indicted in December, he was arrested, forced to resign his powerful public works position, and voted out as grand sachem of Tammany.

His personal world unraveled too. In January 1872 his old comrade Jim Fisk was fatally shot, while walking up the marble staircase of the Grand Central Hotel, by Edward S. Stokes, the spendthrift son of a prominent New York family, who had taken up with Fisk’s mistress Josie Mansfield. As he lay dying, Tweed (out on bail) was at his side. Another bedside mourner was Jay Gould, who had his own problems, stemming directly from Tweed’s fall. The Erie president’s powerful enemies had been circling, but he had successfully fended them off with the aid of Tweed’s judges. Now Tweed was forced to resign from the Erie board of directors, Judge Barnard was impeached and convicted (at the insistence of the Bar Association), and Gould’s position became untenable. He too was forced to resign.

Though his power was shattered, Tweed continually wriggled out of reach of his prosecutors. His trial in January 1873 ended with a hung—some said bribed—jury. In November 1873 he fared less well and was sentenced to a twelve-year term. But after a year in jail, the decision was reversed, and in January 1875 he was released. His enemies immediately slapped him with a civil suit to recover six million of his ill-gotten gains. Unable to come up with the three-million-dollar bail, he was reincarcerated and languished in Ludlow Street Jail. The monotony was broken, however, by repeated home furloughs. In the course of one of these, he escaped and made his way to Florida, then to Cuba, then (disguised as a seaman) attempted to flee to Spain. Arrested by Spanish authorities, Tweed was delivered to an American warship for return to New York. Back again in the Ludlow Street Jail, and now desperate, he agreed to testify (in return for his freedom) about the workings of the Ring. After he did so at great length, however, vengeful authorities (including now-governor Tilden) refused to release him. His spirit broken, he died in prison, of a combination of diseases, on April 12, 1878.

To consolidate their takeover of municipal power, the Committee of Seventy ran their own chairman, William Havemeyer, for the mayoralty in 1872. Havemeyer, now sixty-eight, had been mayor in 1848-49 and didn’t like much of what had happened since then. Elected to City Hall in a divided campaign, Havemeyer and Comptroller Andrew Haswell Green imposed a vigorous retrenchment policy on New York. They laid off city workers and cut salaries of government officials, hoping to drive out professional politicians and draw in public-spirited elites. They jammed the brakes on development to cut costs and lower the taxes of the propertied classes who were Havemeyer’s biggest supporters. Work on the uptown boulevards ceased. Grading of West Side thoroughfares was halted. The viaduct railway was scuttled. Central Park expansion (and maintenance) was curtailed, and work on the proposed Riverside and Morningside parks was pushed off into the future. The elaborate plans to develop the waterfront were canceled and a cheaper, more circumscribed plan adopted. Declaring the city “finished,” the mayor even argued that New York should refuse any further assistance to the Brooklyn Bridge, then rising in the East River

Also in 1872, some of the outraged businessmen and professionals who had toppled Tweed tried to displace the corruption-ridden Grant administration. The collection of dissidents formed a third party, called themselves Liberal Republicans, and nominated the sixty-one-year-old Horace Greeley to run against President Grant. The Democratic Party seconded Greeley’s nomination, hoping to ride his coattails to the White House—against the better judgment of Democratic national chairman August Belmont, who thought the Greeley nomination “one of those stupendous mistakes which it is difficult even to comprehend.” Belmont was right. Grant, the old war hero, aided by boom-time prosperity and a last spurt of northern outrage at Klan outrages, won every northern state. Few municipal reformers backed Greeley, whom they saw as too close to the Democratic Party. They endorsed independent candidates instead, including Frederick Law Olmsted for vice-president. The city’s bourgeoisie stuck with Grant. “I was the worst beaten man that ever ran for that high office,” Greeley lamented. Weakened by the arduous campaign and depressed over the death of his wife just before election, Horace Greeley came home to his beloved New York City to find that Whitelaw Reid had seized control of the Tribune in his absence. Broken in spirit, he died three weeks later on November 29, 1872.

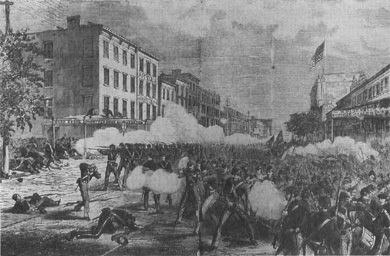

Having crushed Tweed, the forces of order lit into the labor movement, which, in the spring of 1872, had launched its strongest bid yet to institute the eight-hour day. Building trades struck first and, to their delight, got a boost from President Grant. Bricklayers working on the new post office had complained to him about ten-hour workloads. Grant, with one eye on the upcoming elections, denounced this violation of the federal eight-hour law and issued an Executive Proclamation entitling them to overtime pay. This galvanized other construction workers to join the strike, and by early June most small building contractors had knuckled under.

Inspired by these successes, other workers downed tools and walked off. Soon twenty thousand—including plumbers, upholsterers, pianomakers, masons, marble cutters, quarrymen, tin and slate roofers, sugar refiners, and gas men—were fighting for the eight-hour day. The city’s employers dug in their heels, and the test of wills spiraled upward into a near-general strike—the biggest labor conflict in New York’s history thus far—pitting a hundred thousand workers from fifty-two crafts (two-thirds of the manufacturing workforce) against a newly unified manufacturing elite supported by most of the city’s bourgeoisie.

The fiercest clashes came in the woodworking trades. In May militant German journeymen of the Furniture Workers League shut down various woodworking factories. On the other side were the piano manufacturers, who ran the most highly mechanized and subdivided woodworking trades. The most vigorous opposition came from Steinway and Sons, a firm far larger and wealthier than most of the vulnerable cabinetmaker shops who had given in to union demands. Seeking to head off trouble, the company offered workers at its Fourth Avenue plant an increase in pay if they would stick with ten hours. When some accepted, a mass meeting of piano workers (held June 5) denounced the rank-breakers and marched, thousands strong, to ring the factory and muscle the ten-hour men away. Steinway called on the new probusiness city government for police protection, and got it. “Captain Gunner arrived with about 80 men,” William Steinway noted in his diary, “who charged on the strikers and clubbed them on the arms and legs, they running as fast as their legs can carry them.”

The Eight-hour Movement—Procession of Workingmen on a “Strike,” in the Bowery, June 10, 1872, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 29, 1872. Note that many marchers are smoking cigars. Cigar-making remained a major source of employment in New York, although production was shifting from small craft shops to factories and tenement houses. (Courtesy of American Social History Project. Graduate School and University Center. City University of New York)

With momentum faltering, the Iron and Metal Workers League called out its fifteen thousand members, and the strike revved up again. Crowds of blacksmiths surrounded J. B. Brewster’s Carriage Factory and the Singer Sewing Machine’s plant—both bastions of the ten-hour day in metallurgy—and brass founders, pattern makers, wireworkers, pen and pencil makers, church organ builders, brewery workers, packinghouse butchers, and bakers entered the fray.

Now employers organized. On June 18 the industrialists and building contractors joined forces with the woodworking bosses and, at a meeting of over four hundred employers, formed an Executive Committee of the Employers of the City, dedicated to smashing the eight-hour movement—now depicted as the stalking horse for something far worse. As one steam pump manufacturer harangued the meeting: “I see behind all this the specter of Communism. Our duty is to take it by the throat and say it has no business here.”

Soon, indeed, employers brought in the police, who sent platoons, then battalions of men, many of them recent veterans of the Orange Riot suppression, to club picketers away from plants and open avenues for scabs. One after another the strikes crumbled. Steinway and Singer triumphed. The iron men surrendered in July. Many earlier gains were lost, and apart from some in the building trades, most New York workers were forced back to a ten-hour regimen by jubilant employers.

With the municipality’s political and economic order under control, reformers set out to restore decency to its moral affairs, with the earnest young Anthony Comstock serving as point man. Comstock, another New England migrant come to the big city, had been born in 1844 to a once-affluent New Canaan farm family come on hard times, from whom he received a rock-ribbed upbringing as stony as their Connecticut soil. With the outbreak of civil war he joined the army, only to discover it full of “wicked men” who swore and drank. His vigorous opposition to such pursuits did not endear him to his comrades—indeed he discerned a “feeling of hatred” on the part of his fellow soldiers—but, convinced that his critics were “under Satan’s power,” he prayed earnestly, if ineffectually, for their conversion.

After the war, like Horatio Alger, Comstock left Connecticut for New York, where he moved into a rooming house and found work as a porter in a dry-goods store. In a career that Ragged Dick would have envied, he was promoted to shipping clerk and in 1869 made salesman. By 1871 his salary had climbed from five to twenty-seven dollars a week. He used the five hundred dollars he had saved as down payment on a house in Brooklyn, married the daughter of a New York businessman, and joined the Clinton Avenue Congregational Church. For all Comstock’s success, what most occupied his attention was the shocking behavior of his fellow clerks. Comstock didn’t think himself a stuffed shirt—he was fond of practical jokes (of the exploding cigar variety)—but he drew the line at drinking, gambling, whoring, and particularly pornography (a “moral vulture,” which “steals upon our youth in the home, school, and college, silently striking its terrible talons into their vitals, and forcibly bearing them away on hideous wings to shame and death”). Early in 1872 he tried to shut down a circulating library of “vile books,” only to have a policeman warn the owner. Comstock got him dismissed from the force, then teamed up with a reporter from the Tribune, toured the Ann Street and Nassau Street porn purveyors, and organized a (well-publicized) police raid.

The muttonchopped one-man vice squad now came to the attention of Morris Ketchum Jesup, merchant, banker, railroad financier, and president of the Young Men’s Christian Association. Under Jesup’s leadership, the YMCA had been taking a carrot-and-stick approach to combating the deleterious impact of the brothels, gambling dens, saloons, and “licentious books” that distracted young men from serving their employers, saving their money, and rising in the world. In 1868 the Y had built a grand new residence for unmarried men, at Fourth Avenue and 23rd Street, which offered lectures, classes, reading rooms, parlors, and a picture gallery. Additionally, its members had gone to Albany and got the legislature to ban obscene material.

Jesup, himself a Connecticut immigrant of devout but impoverished background intent on imposing an unambiguous moral code on the metropolis, took an instant liking to Comstock. On May 9, 1872, Jesup invited him to meet a group of YMCA backers—leading businessmen (including J. P. Morgan), clergy, and lawyers, men as determined to restore decency to cultural affairs as political ones. They agreed to support his work as a vice fighter by giving him a stipend to supplement his income and a clerk.

Much buoyed by this powerful backing, Comstock now took on Victoria Woodhull, who had been more or less constantly pilloried since her emergence as a feminist spokesperson, with associates and relatives of Henry Ward Beecher prominent among the assailants. On November 2, 1872, she struck back with an article in Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly intended to “burst like a bombshell into the ranks of the moralistic social camp.” That it did. Within hours New Yorkers were scrambling to read “The Beecher-Tilton Case,” in which Woodhull laid bare the story of Henry Ward Beecher’s adultery with Mrs. Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of Theodore Tilton, one of his closest friends and associates.

Woodhull condemned not Beecher’s philandering but his hypocrisy. This was, after all, the minister who had maligned Jim Fisk as a “glaring meteor, abominable in his lusts and flagrant in his violation of public decency.” Indeed Woodhull praised Beecher’s “physical amativeness,” claiming him (with tongue in cheek) as a covert member of the Free Love ranks, and urging him to accept a leadership role in its future endeavors.

Beecher frostily ignored the piece, but Anthony Comstock did not. He approached the district attorney (a leading member of Beecher’s Plymouth Church) with a request for an arrest warrant on grounds that Woodhull and Claflin had violated state law by sending obscene literature—the exposes in the Weekly— through the mails. The DA found the argument compelling, and Comstock, in what would prove to be the opening salvo of a decades-long campaign to suppress public discussion of sexual matters, summoned two police officers to his aid, arrested both Woodhull and her sister, and had them incarcerated in the Tombs, where they spent the month of November. When released on bail in December, Woodhull promptly circulated the hot issue on the black market and gave a dramatically unrepentant speech. Comstock arrested her again. She got herself bailed out again. He grabbed her a third time in February, but after a June 1873 trial, a judge threw out the charges, saying the 1872 law didn’t apply to newspapers.

In 1872, while doing battle against Comstock and Beecher, Woodhull campaigned for President on the People’s Party ticket, with Frederick Douglass as her running mate. This scene, reprinted from M. F. Darwin’s pamphlet, “One Moral Standard for All,” depicts her nomination at Apollo Hall on May 10 of that year. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Woodhull now expanded her attacks on the sexual hypocrisy of New York’s male bourgeoisie. She publicly exposed the Rabelaisian masked balls—those gatherings of “the best men” and “the worst women in our city” in which the boxes of the Academy of Music were used “for the purpose of debauching debauched women; and the trustees of the Academy know this.”

While Woodhull pressed onward, Comstock pressed for stronger legislative weaponry. In January 1873, again with powerful YMCA backing, he traveled to Washington to lobby for federal legislation that would ban obscenity from the mails. His timing was excellent. The Grant administration, swamped by corruption scandals, was in no position to be seen supporting immorality. It didn’t hurt that federal authorities were more dependent than ever on access to New York capital, access controlled by the likes of YMCA stalwart J. P. Morgan. After Comstock exhibited some obscene books and postcards to (putatively) shocked congressmen, they swiftly passed (and the president signed, on March 3, 1873) what soon became known as the Comstock Law. The U.S. government, virtually without debate, had gone into the censorship business.

To enforce the act, Congress instituted the office of special agent of the United States Post Office and gave the job to Comstock. He accepted it, without pay, and would keep it for the next forty-one years of a career devoted (as he said) to hunting down violators “as you hunt rats, without mercy.” Roaming New York City—and, by rail, other cities—armed with warrants, revolver, and handcuffs, he broke down doors, arrested the inhabitants, and confiscated smut. By January 1874 he had seized a small mountain of it—130,000 pounds of books, 194,000 “bad pictures and photographs,” and fifty-five hundred indecent playing cards. No publishers were safe—even those previously considered respectable. Comstock kept Frank Leslie, editor of the well-known weekly, under arrest for advertising obscene books until Leslie promised not to print whatever he disapproved of. He arrested the editor of Fireside Companion for issuing dime novels that Comstock found excessively racy (in later years, Horatio Alger would find his works proscribed).

Comstock steadily broadened his definitions of obscenity. He banned any depiction, no matter how indirect, of the act of intercourse; one arrestee “had box containing figures of hen and rooster which by pulling out lid placed it in indecent posture and was offensive to decency.” He banned any discussion of sexual acts, words for sexual parts, or overly frank discussion of changes in the institution of marriage. He arrested Dr. E. B. Foote, author of Medical Common Sense, a book filled with criticism of sexual taboos that had, by 1870, sold 250,000 copies. “Obscene,” said Comstock, and his was the opinion that counted.

Comstock’s backers were a bit dismayed by this whirlwind of action, especially as some of it generated bad publicity for the YMCA. But they had no intention of abandoning their urban vigilante: though nervous at the notoriety, they applauded the action. After generations of fruitless exhortation, here was someone who would, if need be, coerce people into proper behavior. The Times too applauded the assumption of public power into private hands; true, it resembled the work of “vigilance committees, regulators, or lynch policemen,” but that was a point in its favor.

Still, this was not the sort of image appropriate to the YMCA. The solution was to cut Comstock loose and set up a new organization just to support his crusade. In May 1873 the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice was incorporated, with Anthony Comstock as agent and secretary. Behind him was a blue ribbon board. It included Jesup, J. P. Morgan, William Dodge Jr. (heir to the Phelps-Dodge copper fortune), Samuel Colgate (head of the New Jersey soap business), Alfred S. Barnes (the textbook publisher), and lawyer William C. Beecher (Henry Ward’s son).

Comstock now expanded his purview to encompass the behavior of New York’s bourgeois women.

After the war the American Medical Association had renewed its prewar efforts to suppress abortion. Doctors asserted abortion was morally wrong, in itself and because it helped women evade their maternal duties. An 1868 study found perhaps two hundred full-time abortionists at work in the metropolis and estimated that one out of five New York City pregnancies ended in abortion. This latter number—which included many reputable married females of the better classes—suggested a widespread selfishness, claimed Dr. Horatio Storer, a leader of the crusade to punish both those who performed the operation and the women who sought it. Ladies, Storer said, were aborting simply to seek “the pleasures of a summer’s trips and amusements.” By diminishing the native Protestant birth rate, moreover, they were allowing immigrant Catholics to advance demographically. It was time, therefore, to reaffirm that woman’s place was in the nursery, and certainly not, some doctors muttered privately, in medical school.

In 1868 the State Medical Society pressured the New York legislature into passing the first antiabortion legislation in twenty-two years. The act banned all advertisements alluding either to abortion or birth control. The following year a still tougher law made the destruction of a fetus—at any stage—manslaughter in the second degree, a great victory for physicians. It made little dent, however, in the widespread belief than an early abortion was a woman’s right. City practitioners—notably Madame Restell—continued to thrive. Indeed the brazen Restell regularly turned up at afternoon carriage promenades in Central Park, in a coach pulled by a matchless team of Cuban horses.

The concatenation of Commune, Orange Riot, Tweed prosecution, and labor crackdown drastically changed the moral and political climate. In 1871 the New York Times launched a full-scale attack on abortions, at the same time, and in much the same spirit, as the paper’s assault on Tweed (whose regime, the Times was convinced, connived to keep the trade going). After undercover reporters visited and exposed some of the sleazier of the city’s practitioners, arrests were made, and prosecutors damned defendants in flaming language. One lawyer, referring to Restell’s mansion-office on Fifth Avenue, spoke of “that den of shame in our most crowded street, where every brick in that splendid mansion might represent a little skull.”

At the height of this whipped-up public indignation—concurrent with the October 1871 arrest of Tweed—a young girl, victim of a botched abortion, was found stuffed in a trunk that had been mailed to Chicago. It was traced back to one Rosenzweig, promptly labeled the Fiend of Second Avenue, who was tried, convicted, and almost lynched. Many abortionists fled the city, and many papers stopped carrying the ads of those (like Madame Restell) who remained.

It was in this context that Anthony Comstock not only joined the antiabortion crusade but declared war on contraception generally. He attacked those who advertised abortions on the grounds that references to female complaints and cures, however delicately phrased, were obscene and arrested those who manufactured or retailed “rubber goods for immoral purposes.”

Comstock’s job was made easier in April 1872, when, after the Rosenzweig affair, the state legislature made the abortion-related death of a fetus or woman a crime punishable by up to twenty years. It also banned advertisement, manufacture, or sale of abortion-inducing materials. The following year he made sure that the Comstock Law banned contraceptive devices from the mail, and in June 1873 he got Albany to make the mere possession of obscene matter, including “any drug or medicine, or any article whatever, for the prevention of conception, or for causing unlawful abortion,” punishable by three months to two years at hard labor. By the end of the year he had confiscated 3,150 boxes of pills and powders used by abortionists and 60,300 “articles made of rubber for immoral purposes” and had thrown several abortionists—though still not Madame Restell—into jail.

The response of New York’s bourgeois women to Comstock’s campaign was mixed. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan 6. Anthony’s National Woman’s Suffrage Organization protested an initiative, spearheaded by male businessmen and male professionals, that sought to foreclose women’s access to abortions and information about sex, and muzzle feminist publications and periodicals. Others were intimidated into silence or actively supported Comstock’s crusade as the lesser of two evils. Middle- and upper-class women had been unhappy about the rampant commercialization of sex in New York City. The flagrant spread of concert saloons and brothels provided, in effect, an alternative sexual structure to the family. It facilitated husbandly philandering and freed many men from matrimony altogether. The feminist magazine Hearth and Home complained in 1871 that 125,000 young single men in New York City refused to marry, preferring to live indecent lives and patronize “lower and more infamous” forms of amusement. As contraception and abortion helped sustain this freewheeling system, Comstock’s imposition of respectability helped suppress it.

Feminists who had been ardent proponents of spreading knowledge about sexual physiology rejected Comstockery. The many women who found such openness alarming, on the other hand, were prepared to take shelter in Comstock-inspired prudery. And despite the new access of a handful of females to the professions, women remained economically dependent on men and quite aware that, while individual freedom could bring relief from oppressive customs and laws, it could also pitch women into a competitive world in which the deck was stacked against female players.

The fate of those who transgressed conventional boundaries provided a scary object lesson. Victoria Woodhull’s challenge to Henry Ward Beecher was a case in point. The reverend denied his adultery, and many in his congregation rallied around him and denounced his accusers. When Tilton finally sued his former friend for alienation of his wife’s affections, it led to a sensational 1875 trial, which ended, after six months of testimony, in a hung jury. While respectable opinion didn’t completely exonerate the minister, he soon recovered most of his standing in the community. Beecher boats continued to ferry crowds to Plymouth Church on Sundays; he still got a thousand dollars per lecture, while Elizabeth Tilton was hounded into oblivion. The double standard had survived a most vigorous challenge.

It would be left to a small but highly vocal band of sex radicals to contest, on libertarian principles, the new coercive circumspection. Ezra Heywood (author of “Cupid’s Yoke”) and Robert Ingersoll (who founded the National Liberal League in 1876) struggled against the right of church and state to limit expression of sexual ideas. They boldly printed and distributed “obscenities” and challenged the vice crusaders’ attempt to force discussion of sex and contraception behind closed doors. Comstock went after them too and, after a few temporary setbacks, emerged triumphant. In New York City, De Robigne Mortimer Bennett, an iconoclastic, anticlerical freethinker, helped mount an effort to repeal the Comstock Law that gathered over fifty thousand signatures. But Comstock, who considered Bennett “everything vile in Blasphemy and Infidelism,” nailed him for mailing an “obscene” scientific pamphlet (How do Marsupials Propagate?) and in 1879 got a landmark decision against him.

Another prominent casualty was Victoria Woodhull, attacked not only by Comstock but by her comrades in the IWA. In the aftermath of the disastrous 1872 strike, the International Workingmen’s Association fell into internal warfare between immigrant socialists and American radicals. The Germans thought their native-born allies’ attachment to temperance chauvinistic, their professions of spiritualism preposterous, and their devotion to greenbacks ludicrous, but most of all the Germans had no sympathy with the Americans’ feminism. The Americans found German atheism excessively materialistic, considered socialist devotion to the gold standard incomprehensible, and insisted “the extension of equal rights of citizenship to women must precede any general change in the relationship between capital and labor.” The IWA purged itself of feminists and “fanatics” but, fatally weakened by internal discord and external defeat, eked out an existence for only a few more years, then limped into history. Woodhull’s last attempt to rally feminists and assorted reformers was her People’s Party presidential campaign in 1872, which was crushingly defeated. After this the women’s movement would distance itself from radicalism. So would Woodhull, who in 1876 packed herself off to England, married a nobleman, repudiated her scandalous Free Love views, and settled into respectability and good works.

Among the last holdouts was the sixty-seven-year-old Ann Lohman—Madame Restell. As late as 1878 she was still running her business on Fifth Avenue (though dispensing only pills, not abortions, that industry having been driven underground and turned over to the unscrupulous and the untrained). Comstock, calculating that the once immune Restell was now safely isolated by the new repressive moral climate, called on her incognito, got her to sell him a contraceptive device, and arrested her. He also made sure that every paper in town was invited to witness her arraignment at Jefferson Market Police Court. Restell managed to post bond, though with considerable difficulty as most people were afraid to be publicly associated with her. As the weeks before her trial dragged on, with the press lambasting her daily, she became convinced Comstock would succeed in hounding her back into prison. Rather than accept such a fate, she lay down in her tub, filled it half full, and slit her throat from ear to ear. The New York Times declared it “a fit ending to an odious career.”