In 1879 the national and metropolitan economies swung upward again. Reconstruction was over, the South was wide open for investment, and cotton billowed north again. Out west, the U.S. Army was winning its way to the rich trans-Mississippi territories, and within a decade obstinate Apache, Nez Perce, and Oglala Sioux resistance would be only a memory, the stuff of Wild West shows and dime novels. Farmers were reaping bountiful harvests, just as European crops were coming up short. The balance of trade turned favorable. For the first time in thirty years New York’s bankers, merchants, and industrialists faced no significant obstacles to profit-making. Years of depression had crippled unions. Wages were down, the working day up. Activist judges intervened in economic disputes with admirable partiality on the side of capital. Municipal government was no longer wasting taxpayer money on outdoor relief or public works. The federal government too was in splendid hands. The gold standard was back, the income tax was no more, interest rates were down. Not surprisingly, railroad construction exploded. The need for iron horses to shuttle settlers west, and wheat and ore east, seemed limitless. Annual track construction spun up from 2,665 miles in 1878 to a staggering 11,569 in 1882, inducing tremendous output from steel mills, iron mines, the entire industrial sector.

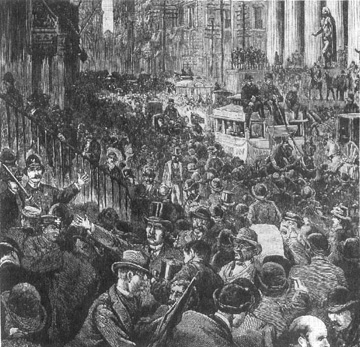

The capital demands of this railroad “boom”—a word first used in this era to describe economic acceleration—revived Wall Street. From 1879 on, frock-coated, silkhatted brokers jostled and pushed at the New York Stock Exchange, buying and selling millions’ worth of stocks amid a great din. Outside, along Nassau, Pine, and William streets, outdoor curb traders created a bedlam of their own, while all around them bank messengers and telegraph boys with yellow envelopes darted to and fro amid the throng. Trading continued at fever pitch through 1882, boosted by the willingness of brokers to extend margin credit—an investor could buy a stock by putting down a mere 10 percent of its purchase price—and by the return of European investors who had sworn they would never again buy American stocks even if endorsed by angels.

But the railroad wars revived as well. Rival barons had agreed to a new “pool” in 1877—a cartel to curtail competition, fix prices, and divvy up markets. Unenforceable at law, the arrangement was soon in tatters. Supply rapidly outstripped demand. When one line proved a route’s profitability, others jumped in and built another, forcing the established firm to slash rates. Profits spiraled downward. Faced with catastrophe, the roads formed new pacts, only to find them quickly violated by predators.

The biggest shark of all was Jay Gould. With fellow manipulators like Russell Sage, Gould bought up western lines, puffed their stock, sold out at profitable highs, and turned a final profit by selling short on the way down. Gould joined pools, then sabotaged them without compunction, precipitating yet another round of conflict.

By the early 1880s each major line was struggling to transform itself into a giant, self-contained, nationwide system capable of withstanding all possible rivals. Gould expanded his core lines in all directions and by 1882 owned over fifteen thousand miles of road, 15 percent of the national trackage. William Vanderbilt retaliated with his own massive expansion program. So did Henry Villard and the group of New Yorkers—including August Belmont, Robert Goelet, and the young Edward H. Harriman—who controlled the Illinois Central. But all this did was reproduce the warfare at a higher level.

By 1883 the combat was buffeting Wall Street. At first there were just isolated failures: high-flying financiers like Henry Villard plummeted suddenly into bankruptcy. Then, as competition blighted earnings, rail stocks declined, and iron stocks dipped downward. Alarmed European capitalists retreated again across the Atlantic. Rumors spread of an impending collapse. The president of the Exchange asserted that “the situation now is in no respect like that which preceded the panic of 1873”—a sure sign of trouble.

By 1884 the contraction had become so pronounced, the speculative marketplace so vulnerable, that anything might have triggered disaster. In the event, the unwitting precipitant turned out to be Ulysses S. Grant Sr.

After the war, an unscrupulous young man named Ferdinand Ward had plunged into the stock market and scored with a series of modestly successful speculations. On the strength of this, Ward persuaded Ulysses “Buck” Grant Jr., airhead son of the ex-president, that he could make him a millionaire overnight. Grant and Ward, stockbrokers, was born. Next, the smooth-talking Ward convinced Grant Senior—the general had moved to New York City in 1881 and settled into a brownstone on 66th Street—that he could advance his son’s career by joining the firm too. Then Ward went to James D. Fish, president of the Marine National Bank, and hinted lucrative government contracts were on the way to the ex-president’s firm. Fish took the bait and advanced large sums of depositors’ money, which Ward used for stock market speculations.

Ward, unfortunately, bet on a bullish market just as stocks turned bearish. He lost heavily but continued to pay dividends to Grant and Ward’s investors—including the Grants—by arranging further loans from Marine Bank. The Grants, père et fils, thought themselves rich.

In April 1884, with both Ward and Marine Bank desperate for funds, Ward went to the credulous general and said the bank, and thus his brokerage house, were in a spot of temporary trouble. Could the general borrow $150,000 from William Vanderbilt to tide things over? Grant did as requested, though Vanderbilt, who like most rich businessmen had a great affection for Grant, said: “To you—to General Grant—I’m making this loan, and not to the firm.”

Grant turned the check over to Ward, who promptly cashed it, pocketed the funds, and prepared to flee the city. He didn’t move quickly enough. Fish announced the Marine Bank’s failure. Crowds of enraged depositors milled outside its closed doors, baying for Fish’s head. They organized a posse, captured Ward, and clapped both in Ludlow Street Jail. When word reached Grant at his G&W office, the stunned old man, a dead cigar clutched between his lips, hobbled out into the street and headed home, as cynical Wall Streeters doffed their hats out of respect for the tragedy unfolding before them.

More banks collapsed. Eminent directors were revealed to have stolen millions and plunged, ineptly, into railroad securities. Stocks nosedived. Panic swept the district. Brokerage houses failed. High rollers were laid low: Gould himself came close to collapse.

General Grant went bankrupt. The public, correctly convinced he had known nothing of his partner’s swindles, offered sympathy and cash. Grant, down to his last eighty dollars, accepted reluctantly. Greatly distressed about his debt to Vanderbilt, he signed over his properties, medals, and presidential memorabilia to the financier. Vanderbilt refused to accept them, until Grant pointed out that creditors would take them anyway; the magnate turned the medals over to the government.

Detail from The Panic of 1884, from Harper’s Weekly, May 24, 1884. (Library of Congress)

At this darkest hour Grant recalled a request by Century Magazine that he write articles on the Civil War. He produced a series of successful pieces, then landed a book contract for his memoirs. In 1885 Grant learned he had contracted terminal throat cancer. Despite great suffering, he pushed on and finished the book—later a spectacular success and the salvation of his heirs—before dying on July 23, 1885.

His adopted city did better by him in death than it had in life. Grant’s body lay in state at City Hall for three days, then embarked on a six-mile-long funeral procession through the city’s streets, past an estimated million and a half spectators, to a temporary tomb on Riverside Drive. The following year, the Department of Parks authorized creation of a permanent memorial and gravesite, and after April 27, 1897, when Grant’s Tomb was finally dedicated, the old soldier finally lay in peace beside the Hudson.

The stock market chaos of 1884 proved less catastrophic than the breakdowns of 1819, 1837, 1857, and 1873—in part, the Nation observed, because previous crises had broken upon good times “like thunderclaps out of a clear sky.” In the mid-1880s, however, business had already slumped, and unemployment had risen to 7.5 percent from its normal 2.5 percent. The panic’s limited impact was also due to prompt and decisive action by the financial community itself, now far better prepared to meet such crises. The Clearing House pumped credit into the system, and dozens of banks and brokerage firms were hauled back from the precipice. One of the coolest and boldest players was J. P. Morgan, who stepped in and purchased stocks almost as fast as panicked speculators sold them, thus helping restore confidence. When the crisis passed, Morgan had emerged as Wall Street’s preeminent leader.

Morgan, chewing on his big cigar, surveyed the bloody economic battlefield from the mahogany partners’ room at 23 Wall and decided it was time to end the railroad wars. Morgan had himself participated in them vigorously, bankrolling combatants and mending casualties, both highly lucrative endeavors. But the London investors he represented were fed up, as he barked at one recalcitrant railroad president: “Your roads! Your roads belong to my clients!” With competitive conflagrations now threatening Wall Street itself, Morgan and other New York investment bankers decided to intervene aggressively.

On a hot and muggy July day in 1885 a clutch of railroad executives boarded Morgan’s 165-foot, black-hulled steam yacht, the Corsair. While the vessel cruised up and down the Hudson River, the banker spelled out his displeasure at the “fever for building and extending competitive lines.” The assembled magnates agreed to reject unbridled competition and establish spheres of influence. But the “Corsair Compact,” like previous pools, lasted little more than a year. The wars commenced again, this time with the Vanderbilts as rate cutters and Gould promoting stability. There seemed no way to quit the free enterprise merry-go-round, so the ride spun on, propelled by fear of failure, accumulated rancor and mistrust, monumental egoism, and the sheer exhilaration and momentum of combat. In 1887 matters worsened further when farmers, passengers, small businessmen, and the New York City merchants assembled in the National Anti Monopoly League convinced Congress to outlaw pools altogether. Wars of unparalleled ferocity chewed up earnings, and the economy tipped downward once more. In 1888 Morgan summoned the presidents of sixteen major roads to the library of his Madison Avenue mansion and hammered out another pact—which quickly crumbled.

Industrialists, facing much the same dilemma, had meanwhile invented the “trust,” a legal device they believed might solve the problem. Oil refiner John D. Rockefeller and his leading rivals had joined forces in a Standard Oil cartel that used its collective domination of processing capacity and railroad transportation to force thousands of combative oil producers to stabilize prices, with William Rockefeller dispatched to New York City to handle the Standard’s export operations. When competitors threatened to bypass this arrangement by launching pipelines that would pump crude oil directly to New York Bay for refining and export, the Standard fought back. It gained control of most independent metropolitan-area outlets—folding Charles Pratt’s Astral Oil company (which Rockefeller had bought up secretly in 1874) with other Hunter’s Point and Newtown Creek operations into Standard Oil Company of New York (SOCONY)—and ran its own pipeline from the Pennsylvania oil fields to newly centralized operations in Bayonne, New Jersey.

The problem was that this enormous enterprise lacked a legal and administrative superstructure—until 1882, when New York attorney Samuel C. T. Dodd conceived the Standard Oil Trust. Shareholders of the cartel’s now forty companies exchanged their stock for certificates in the trust, which in turn was authorized to “exercise general supervision over the affairs of the several Standard Oil Companies” out of a unified headquarters in New York City. Here, clearly, was an outfit that knew how to overcome competition, and indeed boasted of it: “The day of combination is here to stay,” John D. declared. Industrial consolidation, he announced, was a step up the evolutionary ladder. It represented the “survival of the fittest,” Rockefeller said, “the working out of a law of nature and a law of god.”

Inspired by the Standard’s example, ten other processing industries established trusts and all but two located their central offices in New York City. In 1887 Elihu Root, corporate attorney and pillar of the Manhattan Bar, helped Henry O. Havemeyer wring competition out of one of New York’s oldest industries. Seventeen metropolitan sugar refining companies, representing 78 percent of the nation’s capacity, came together in a Sugar Trust, which consolidated its members’ production and purchasing and proceeded to drive remaining competitors out of business, a process it acclaimed as advancing “the common good.”

Small businessmen, farmers, and consumers disagreed. They denounced trusts for raising prices and concentrating power. In 1890 these opponents won passage of the Sherman Act, which declared the trustee device an illegal restraint of trade. Gloomy businessmen faced another murderous round of free enterprise.

At this juncture, Wall Street attorneys James Brooks Dill and William J. Curtis (a partner in Sullivan and Cromwell) took a new tack. Dill drafted a law that permitted one manufacturing company to purchase and hold stock in any other company “manufacturing and producing materials necessary to its business.” In effect it allowed competitors to combine in a single corporate body. This simple and elegant solution was enacted by the New Jersey state legislature after Dill and Curtis, both Jersey residents, convinced the governor it would attract new corporations and strengthen the state’s budget. It soon passed judicial muster, as courts found that elements of a single firm, no matter how large, could act in concert without their association constituting an illegal restraint of trade.

Between 1890 and 1893 half a hundred companies converted to the corporate holding company form. Some were old trusts, forced into reformatting by the Sherman Act: when the Sugar Trust was declared illegal in 1889 and ordered dissolved, Root recommended the Havemeyers try incorporation, and within a few years the new American Sugar Refining Company controlled nearly 98 percent of the national output. Some of the new corporations were “Morganized” railroads, formed when J. P. Morgan and other New York City investment bankers reassembled bankrupt competitors into viable corporate entities, set up their headquarters in Manhattan, and pocketed million-dollar fees and directorships for their trouble. Some were metropolitan wholesale merchants—like H. B. Claflin’s—who had discovered the virtues of the corporate form.

Some of the new corporations were industrial concerns, like the American Tobacco Company (1890), a newcomer to New York. In the mid-1880s James Buchanan Duke, a North Carolina chewing tobacco manufacturer, switched to cigarette production. Duke relocated his operations to Manhattan—the largest urban tobacco market in the nation and an industry center since Pierre Lorillard had opened his snuff factory on Chatham Street back in 1760. Backed by lines of credit from New York financial houses, Duke opened a massive factory at First Avenue and 38th Street, using cheap female labor and fifteen of the new Bonsack machines capable of producing 120,000 cigarettes a day. By 1889 he was rolling over eight hundred million cigarettes annually. The following year Duke subsumed his five leading competitors into his giant new ATC corporation (and a few years later P. Lorillard Company as well).

The financial community rapidly thawed its frosty attitude toward “industrials.” Bankers and brokers had long considered manufacturing operations too small or too unstable to warrant investment. Through the 1880s the New York Stock Exchange had refused to list industrials, with the single exception of the Pullman Palace Car Company. Now funds flowed to newly merged companies. By 1897 eighty-six industrial corporations, each capitalized for over a million dollars, had been formed and financed, most of them on Wall Street. Mining and petroleum stocks traded in unprecedented numbers. Foreigners plunged in too and by the early 1890s had sunk roughly three billion dollars into U.S. firms, up 50 percent since 1883. Poor’s, Moody’s, and Dun’s began publishing analyses of the new corporations, and many began filing annual reports with the Exchange.

It seemed, finally, that a stable future was coming into being, one in which incorporation would replace competition, antagonistic companies would be consolidated, and their oversight operations would be centralized—in New York City, emerging capital of an emerging corporate economy.

In the 1880s and 1890s many industrial and railroad magnates relocated themselves—as well as their corporations—to Manhattan. Cleveland’s John D. Rockefeller joined his brother William in 1884. Collis P. Huntington came in from California; the Armours arrived from Chicago; Andrew Carnegie shifted from Pittsburgh. They and their companies were drawn, chiefly, by the gravitational pull of money. They wanted direct access to the great investment banks and their connections to vast pools of domestic and foreign capital. New York was host to virtually all the leading firms: Drexel, Morgan (which in 1895 became J. P. Morgan and Company); August Belmont and Company (run after his death in 1890 by his son August Junior); Kuhn, Loeb (led, after the original partners retired in 1885, by Jacob Schiff); and the Seligmans, Lehmans, and Speyers. Even Boston banks like Lee, Higginson and Kidder, Peabody felt obliged to open outlets in New York.

Some newcomers entered the banking world themselves. The Rockefellers cycled their oil profits into the National City Bank, Moses Taylor’s old operation until his death in 1882. From 1891 it was in the steady hands of the steely James Stillman (two of whose daughters married sons of William Rockefeller), and Standard Oil connections and cash would make National City Bank a power in the city.

Manhattan was attractive to businessmen for other reasons too, especially its great assemblage of experts. Among the vast array of talented metropolitan professionals, none were more crucial to the emerging corporate order than lawyers. Since George Templeton Strong died in 1875, firms like his had been joined by a host of crack legal firms. They specialized in providing legal, managerial, and financial advice to large corporate clients on a regular basis, not just at the point of litigation. Indeed many corporate attorneys withdrew from trial work altogether, dealing instead with the growing number of regulatory state agencies that corporations were answerable to, or serving as businessmen’s emissaries and lobbyists (shuttling back and forth between Washington or Albany and New York City), or serving in public office themselves.

Lower Manhattan grew thick with corporate law firms. Bangs and Stetson, ancestor of Davis, Polk, and Wardwell, boasted Francis Lynde Stetson, known as J. P. Morgan’s attorney general for his work counseling the financier on industrial and railroad reorganizations. When Grover Cleveland lost the White House in 1888, he moved to New York City and worked at Bangs, Stetson, forming close alliances with Morgan and other financiers before returning to Pennsylvania Avenue in 1892.

Morgan also turned to William Nelson Cromwell of Sullivan and Cromwell (1879), as did Henry Villard and E. H. Harriman. Anderson, Adams, and Young (1866)—later Milbank, Tweed, Hadley, and McCloy—became the “Rockefeller firm” in 1888 when George Welwood Murray brought in John D. as a client; Murray remained his legal adviser and confidant for decades. Joseph Choate counseled Standard Oil and American Tobacco, Elihu Root advised big sugar, and future legal giant Henry Lewis Stimson got his start advising railroad and streetcar companies.

Most firms remained modest in size—five partners constituted a large operation—but some of them, Strong would have been glad to know, began to replace the old apprenticeship system, which had relied on unpaid law clerks, with a more professional approach. Walter S. Carter’s firm, Chamberlain, Carter, and Hornblower, began hiring graduates of elite law schools as paid “associates,” who specialized in particular departments (corporate, real estate, trusts and estates) and served as the pool from which future partners were drawn. Among the first recruits and graduates was Paul D. Cravath, a brilliant Columbia Law graduate who would later develop the new approach so extensively at his own firm that it became known as the “Cravath system.” At the same time, law schools and the “white shoe” firms they fed became ever more socially exclusive. There were a few Jewish or Catholic organizations, and after 1890 women were admitted to NYU Law School, but the new procedure helped make Wall Street law firms into overwhelmingly white, Protestant, upper- or middle-class, Republican, and male bastions.

New York’s attractiveness to corporations was enhanced by its advertising industry, which underwent a transformation akin to the legal profession’s. Advertising had a dubious reputation in the postwar era, due in part to its most prominent clients: the patent medicine manufacturers who laced their products with alcohol and opium. Business self-promotion seemed Barnumesque; it smacked of desperation and unsoundness. Even the best agencies, like Samuel Pettengill, New York’s and the country’s largest, shilled for newspaper and magazine publishers and lied shamelessly about circulation figures to wrest higher rates from advertisers.

The throng of top hats in this downtown lunchroom conveys the ever-increasing density—and thoroughly masculine tone—of the city’s business district during the 1880s. Harper’s Weekly, September 8, 1888. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

George P. Rowell enhanced the industry’s image when he began bringing out annual editions of Rowell’s American Newspaper Directory, which provided reasonably accurate figures on circulation and rates for over five thousand U.S. and Canadian papers. By evaluating media, he shifted the business toward representing advertisers rather than publishers. In 1888 Rowell started a trade journal, Printer’s Ink, that advertised the very notion of advertising. In the same year, Pear’s Soap obtained clerical benediction for its product, and for the practice of promotion itself, from Henry Ward Beecher’s cautious testimonial: “If cleanliness is next to Godliness, soap must be considered as a means of Grace, and a clergyman who recommends moral things should be willing to recommend soap.”

Carlton and Smith, another New York agency, also gained respectability by convincing Methodist magazines that running ads was both wise and virtuous. By 1870 the firm worked with four hundred religious weeklies, many of them headquartered in New York. William Carlton’s young assistant James Walter Thompson followed this up by persuading genteel journals like Scribner’s and Harper’s that they too could carry ads without losing integrity or offending subscribers. In 1878 Thompson bought Carlton out and renamed the agency after himself.

“Advertising is the steam propeller of business success,” Rowell claimed, and giant corporations and insurance companies agreed. They turned to professionals like Thompson, and the growing number of firms clustered around Newspaper Row, to create copy rather than simply broker it. Consumer goods manufacturers used ads to familiarize a national market with their product’s “brand name.” In the mid-1870s a New York firm, Enoch Morgan’s Sons, peddled its scouring soap by adopting a Latinsounding brand name (Sapolio) and giving retailers pamphlets that sang its praise in verse penned by Bret Harte, then scratching out a marginal living in the metropolis. In 1884 the firm hired a professional advertiser to place its proverbs (“Be Clean!” “Sapolio Scours the World”) in publications across the country, posted them in streetcars, and blazoned them on a huge sign in New York harbor.

Companies relied on metropolitan agencies to promote types of products too. Admen taught consumers to prefer breakfast cereals in boxes, rather than scooped from grocers’ barrels; to shave themselves, rather than patronize barbers. By 1889 Duke’s American Tobacco Company was spending eight hundred thousand dollars a year to expand the cigarette-smoking public, win tobacco chewers and cigar smokers over to the newer product, and force retailers to distribute his merchandise. Ad agencies placed Duke propaganda in papers and periodicals, on billboards around the city, in programs for theatergoers and handbills at ballfields and boxing matches. In the 1890s other corporate manufacturers used professional pitchmen to launch new commodities, and campaigns designed for Procter & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive, Pabst and Postum, Coca-Cola and Cream of Wheat, similarly dwelt on the compatibility of their wares with modern urban lifestyles.

The number of ad agencies swelled from forty-two in 1870 to over four hundred by the end of the 1890s. Like law firms, they grew larger and more internally specialized. At J. Walter Thompson’s, “account executives” supervised copy writing for particular companies, then liaised with their counterparts in the corporation’s sales and marketing divisions, and with the advertising departments of New York’s newspapers as well. In the 1870s the daily press had gotten less than one-third its income from advertisements. As journalism’s costs increased, papers relied more heavily on such revenues, which jumped to 44 percent of income by 1880 and 55 percent by 1900. The ratio of editorial to ad matter swung from seventy-thirty to fifty-fifty in the same period, and self-promotional gambits flourished as papers sought to assemble an audience to sell to advertisers.

Burgeoning professional and corporate concerns needed lots of office space. Continental-scale companies like American Tobacco had to control the flow of product from factory to retailer, oversee sales agents throughout the country, maintain a large central depot in New York, audit costs, manage labor, track inventory, compile reports, pay taxes, and initiate legal transactions. Companies with international outreach, like I. M. Singer and Company—led by Edward Clark since 1876, the year after Singer’s death—established agencies in Latin America, Canada, and the Far East, which dispatched reports back to the central office in New York City. Sales, purchasing, legal, auditing, and manufacturing departments, in turn, required ever-expanding support staffs: typists and stenographers to handle intra- and extra-company correspondence, clerks to file it all, office boys to handle miscellaneous chores.

Particular entities had special space needs. Insurance companies needed to keep huge record bases for premium and claims payments, manage investments, and develop actuarial statistics. In the case of a company like Metropolitan Life, which sold “industrial insurance” to workers, headquarters had to direct the army of agents who sold policies and collected premiums each week. Law firms needed bigger libraries as national reporting of case law expanded the number of publications to be researched. Specialized segments of the import-export fraternity (iron and metal, petroleum, produce, cotton, coffee, and coal) needed their own gathering places; no longer would a single Merchants’ Exchange do.

To meet this demand, Manhattan’s real estate industry—itself newly organized and housed in a Real Estate Exchange (1883)—generated a tremendous volume of commercial construction, much of it now in red brick neo-Renaissance rather than Second Empire, though mansard roofs remained popular. Some construction was commissioned, but much was erected “on spec” for rental to bankers, brokers, and railroad and insurance companies; the building boom created havens for capital in more ways than one.

The result was a dramatic enlargement—horizontally and vertically—of the city’s business district. The high cost of land encouraged tall towers. “Real estate capitalists,” according to “Sky Building in New York,” an 1883 article in Building News, had “suddenly discovered that there was plenty of room in the air, and that by doubling the height of its buildings the same result would be reached as if the island had been stretched to twice its present width.”

In 1882 the cornerstone was laid for George Post’s mammoth, arcaded Produce Exchange. Over the next two years, it rose at the corner of Broadway and Beaver—site of Peter Stuyvesant’s weekly “Monday Market”—until it loomed ten stories tall over Bowling Green. In 1884 William Rockefeller commissioned a headquarters to house the new Standard Oil Trust at 24-26 Broadway, and two years later its ten stories were filled with managers and employees directing the production, refining, and marketing of oil. By the end of the 1890s over three hundred buildings nine or more stories tall would have gone up in Manhattan.

Though such structures did not overtop the previous era’s Tribune and Western Union buildings, they did surpass them in technology. Most lofty predepression structures had been masonry buildings, whose thick weight-supporting walls ate up floor space and dictated small windows. Post’s Produce Exchange used cage construction: iron columns and girders carried the weight of the floors, allowing exterior walls to get slimmer. Post also experimented with “skeleton” construction for some of the walls, using a metal frame to support them as well.

New York ambled farther into the technological future in 1888, when Bradford Lee Gilbert, an experienced railroad station architect, announced he would raise an eleven story building, 158 feet tall, that relied completely on skeletal construction. His decision was immediately attacked by architects, engineers, newspapers, and public officials who believed such a structure would be precarious. Gilbert defended himself by pointing to recent engineering developments. Gustave Eiffel, for example, had just designed an internal steel-and-wrought-iron armature for the 151-foot Statue of Liberty (completed in 1886) that could withstand a wind load factor of fifty-eight pounds per square foot. At 50 Broadway, Gilbert would use the most up-to-date wind bracing, using iron diagonals in each bay to transmit wall weight through girders and columns down to the footings and foundation of timber piles driven forty feet down to hardpan.

Despite the skeptics, Gilbert’s Tower Building won a city construction permit and overcame the worries of the owner, who feared his narrow building (only twenty-one feet wide) might well blow over. One blustery Sunday morning, the usual gawkers were watching laborers work on the building’s tenth story, when the weather turned really fierce. Throngs poured down to Broadway expecting to see the thin tower topple. As the wind howled, Gilbert clambered to the top, lowered a plumb line, and discovered to his great satisfaction that the building vibrated not at all.

Gilbert’s design ambitions were less daring than his technological ones. Eschewing the approach favored by Chicagoans of having exteriors “honestly” match construction principles, Gilbert swathed the slender base in rusticated stone and enslabbed the remainder with a conventional facade. Just looking at the completed Tower Building in 1889, one would never have known that New York had entered a new era. But after Joseph Pulitzer’s building was finished the following year, there would be no mistaking the fact.

In 1888 the New York World’s publisher had the great satisfaction of buying up French’s Hotel at Park Row and Frankfort Street and having it torn it to pieces. During the Civil War, the elegant establishment had ejected Pulitzer, then a newly arrived Hungarian immigrant and volunteer Union Army cavalryman, because his frayed uniform annoyed the fashionable guests. Pulitzer had grand plans for the site. In the previous few years, his newspaper had dwarfed the circulation of James Gordon Bennett’s Herald and Charles Henry Dana’s Sun. Now he would have George Post erect an edifice that would dwarf his competitors’ nearby buildings, though it would not be as technologically sophisticated as Gilbert’s Tower Building, as Post opted here for cage construction.

On December 10, 1890, the governor and mayor teamed up to celebrate the opening of Pulitzer’s dazzling 309-foot structure—the tallest building in the world. The World tower was topped by a glittering gilded dome, which now would be the first thing to strike the eye of passengers on vessels arriving in the harbor. It was also the first building to overshadow Trinity Church (284 feet), physical ratification of the passage of metropolitan power from sacred to secular. At the top was Pulitzer’s huge semicircular office with three great windows, frescoed ceilings, and walls of embossed leather. One wag reportedly got off the elevator at the top floor and in a loud voice asked, “Is God in?” The editors on the eleventh floor were delighted to find they could lean out the windows and “spit on the Sun.”

Appropriately enough, in the years following Pulitzer’s coup, the term “skyscraper” first gained common currency. It was not a novel word, having had a long history of other associations. Since the eighteenth century it had been used to describe the triangular sails, set above the royals in calm latitudes, called skyscrapers or moonrakers due to their great height. Now, in the early 1890s, it fastened itself irrevocably to the tall buildings sprouting up in lower Manhattan. The new principle of skeletal construction won official sanction, building laws were revised appropriately, and the city made clear its willingness to tear down old masonry structures and erect steel ones, to the delight of ironmasters like Andrew Carnegie and Abram Hewitt.

More was involved here than a prosaic expansion of commercial office stock. In succeeding so admirably in overarching its competitors—making runts of the Times, Herald, Sun, and even the Tribune, whose campanile peaked at a paltry 260 feet—the World Building broke new cultural as well as material ground. Pulitzer’s publishing success owed as much to his paper’s exuberant self-advertising and ferociously competitive spirit as to its innovative content. His architectural initiative extended this warfare onto a new terrain. The World Building was more than a mere office building; it was a corporate self-proclamation, a brand name shouting itself in iron and stone, a shrewd Barnumesque statement by a man well aware that appearances could constitute reality.

Other corporate moguls would follow Pulitzer’s lead and seek their own boardroom-eyries. It would be a few years yet before the process accelerated sharply, but soon a corporate competition for sensational self-presentation—and rentable floor space—would be unleashed. The ensuing frenzied space race would drive New York spectacularly skyward.

The city’s silhouette was also transformed in these years by two devices that became (and have remained) two of New York’s most distinguishing features: water tanks and steam pipes.

As commercial buildings rose to six stories, beyond the reach of fire ladders, and then even higher, beyond the reach of fire hoses dependent on Croton-generated water pressure, the fire department, city government, insurance industry, and tall-tower occupants grew steadily more alarmed, especially when it became clear how quickly flames shot up elevator and air shafts. Western Union, whose building was among the first to confront this problem, had adopted an extremely costly solution. The company dug wells seventy feet deep in its cellar and installed powerful steam pumps to drive the water up through iron mains to the roof, from which heavy streams of water could be played on surrounding buildings. This was not a practical solution to mounting fire losses—which in the dry-goods district alone surpassed six million dollars between 1877 and 1882, less than a third of which had been covered by reluctant insurers. In the latter year the burning of the former World Building on Park Row produced four hundred thousand dollars in damages and twelve deaths, starkly underscoring the peril.

Water sprinklers were part of the answer. The Parmelee Automatic Sprinkler, a heat-triggered device connected to piping installed on each floor, was introduced in 1874 and replaced in 1881 by the improved Grinnell Sprinkler. But sprinklers, as much as hydrants and hoses, required a sure source of pressurized water. The solution, adopted at first on a piecemeal basis, was to have barrelmakers construct a bulky wooden water tank, which looked like a huge washtub on stilts, up on the roof, where it gravity-fed water into the sprinkler pipes that wove back and forth through the building beneath. Fire insurance companies lowered rates on buildings that installed these tanks. In the 1890s, companies emerged to build them (of which two remain, the Rosenwach Tank Company and Isseks Brothers). And the city’s Building Code was amended to require them (or a cellar pump equivalent) on all buildings over 150 feet tall.

Another solution to problems raised by tall buildings was the creation of a network of underground steam pipes to heat them. If each of the new behemoths had a separate heating plant, their gargantuan coal requirements, which would have to be delivered through narrow downtown streets, would soon have rendered the area impassable. To obviate the problem, the New York Steam Company, formed by a merger of competitors in 1881, got a Common Council franchise to lay such pipelines (for which it paid a paltry hundred dollars a year) and in 1882 supplied its first customer, the United Bank Building at Wall and Broadway. By year’s end sixty-two clients in the Wall Street area had signed on to be connected to the Steam Company’s boiler plant at Dey and Greenwich. By 1886 it had 350 customers and five miles of mains, and to this day visitors are periodically startled to see clouds of steam erupt from beneath the streets, as if the city rested on a foundation of geysers.

Installing district steam heating mains, Scientific American, November 19, 1881. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

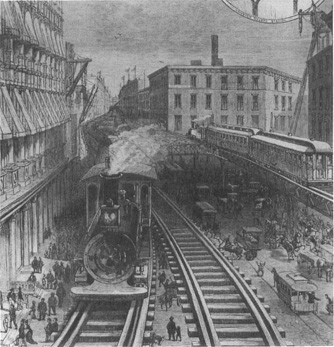

Conduits below were matched by conduits above, as the system of elevated railroads was spurred to fruition by the need to accommodate the city to the growth of corporate enterprise. Rapid transit made the skyscrapers possible by ferrying vast numbers of uptown workers to the downtown high-rise business district, and indeed the “els” accelerated tall-tower construction by driving property values sky high and making efficient use of space ever more desirable.

During the depression, the availability of cheap labor had galvanized promoters to win passage of a Rapid Transit Act (1875), which authorized handing out franchises to private entrepreneurs, and by the early 1880s locomotives were steaming up and down Manhattan. On Ninth Avenue, Charles Harvey’s old road, rebuilt and extended, reached 81st Street in mid-1879, spurring long-delayed development on the Upper West Side. By 1881 the track continued on to 110th Street, where, at the spine-tingling height of sixty-three feet, it swerved giddily eastward to Eighth Avenue, then loped on up to the Harlem River at 155th. At 53rd Street a crosstown feeder linked the Ninth Avenue line to the Metropolitan (formerly the Gilbert) Elevated Railway, whose trains chugged at twelve miles an hour up from Rector Place to Sixth Avenue and on to Central Park.

After December 1878 the New York Elevated Railroad Company’s Third Avenue El stretched from South Ferry up to 129th Street. The company obligingly ran cars all through the night—“Owl Trains” every 15 minutes—which conveyed homeward late workers in the newspaper offices or carousers out on the town, rolling northward across the gloomy and still largely untenanted Harlem flats while the lights of Astoria twinkled across the water in the distance. From 1880 it was paralleled by the Manhattan Railway Company’s Second Avenue road that ran north from Chatham Square.

The new transport lines were not restricted to Manhattan. At first, Third Avenue El passengers bound for the Bronx could only transfer—for a separate fare—to the socalled Huckleberry Line, a horsecar that meandered along the Annexed District’s Third Avenue so slowly that passengers could hop off, pick huckleberries in the fields, and reboard the same car. After 1886, however, the Suburban Rapid Transit Company (1880) ran an elevated service that crossed the Harlem River on an iron drawbridge and (by 1891) traveled up Bronx’s Third Avenue through Mott Haven, Melrose, and Morrisania to 177th, spurring a building boom along the corridor. Passengers bound for the Annexed District could also connect with the New York and Northern (which became the New York Central’s Putnam Division) running up through Highbridge, Morris Heights, and Kingsbridge. Or they could catch the New York and Harlem Railroad, whose ash-spewing locomotives carried them up the Bronx’s central corridor, past Mott Haven’s solid brick clock-towered station, through Melrose, Morrisania, Tremont, Fordham, Williamsbridge, and on past Woodlawn’s country mansion station with its landscaped flower beds, to White Plains and points north. Wealthy folk could simply hop the Hudson line to Riverdale.

Steam engines at the Franklin Square Station of the Second Avenue El. At the left are the offices of Harper & Brothers, the largest publishing house in the United States at the time. Harper’s Weekly, September 7, 1878. (©Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

Southbound travelers, once they reached the Brooklyn Bridge—which opened with great fanfare in 1883—could take a cable-drawn car, which commenced operation in 1885, from Park Row to Sands Street. From there—also after 1885, when Mayor Seth Low helped inaugurate it—Brooklyn Elevated Company trains (the city’s first) ran through downtown to Lexington Avenue, then headed east to Broadway and Gates. A rival, the Kings County Elevated Rail Road, established service along Fulton Street to Nostrand Avenue by 1888, to Brownsville by 1891, and to East New York and the city line in 1893. By that year Brooklyn’s elevated system was complete, differing companies having built the Bay Ridge, Myrtle Avenue, and Broadway lines. These trains handled over thirty million passengers annually, most of them commuting from homes in Brooklyn to jobs in Manhattan.

Different lines served different clientele and had correspondingly different styles. Manhattan’s Sixth Avenue El, which transported a predominantly middle-class ridership, was built for delight as well as convenience. Its dainty green stations, topped by graceful iron pavilion roofs, were designed by landscape artist J. F. Cropsey to simulate tasteful cottages and contained heated, gas-lit waiting rooms for gentlemen and for ladies. The trains that pulled up were equally ornamental, their Pullman palace-style cars manned by conductors in braided blue flannel uniforms.

The Third Avenue line, a working-class conveyance, was not quite as spiffy, though it had its devotees. The Marches—a fictional middle-class couple in William Dean Howells’s Hazard of New Fortunes (1890)—were thrilled by the theatricality of nighttime rides on it, by the “fleeting intimacy you formed with people in second-and third-floor interiors.” You might see, as you passed their windows: “a family party of workfolk at a late tea, some of the men in their shirt-sleeves; a woman sewing by a lamp; a mother laying her child in its cradle; a man with his head fallen on his hands upon a table; a girl and her lover leaning over the windowsill together.” At 42nd Street, the Marches noted, you could look south along the long stretch of “track that found and lost itself a thousand times in the flare and tremor of the innumerable lights.” The couple gazed in fascination at “the coming and going of the trains marking the stations with vivider or fainter plumes of flame-shot steam.”

Not everyone was quite so taken with the trains. Many of those in the windows the Marches swept by complained furiously about ear-splitting noise, soot and cinders, and those “plumes of flame-shot steam”—which seemed far less picturesque at close quarters. Stephen Crane, stirred to more mordant imagery than Howells’s, wrote of the darkened Bowery where “elevated trains with a shrill grinding of the wheels stopped at the station, which upon its leglike pillars seemed to resemble some monstrous kind of crab squatting over the street.” The truly powerful denizens of Fifth, Park, and Madison had already banned elevateds from their avenues. Finally, in 1883, some of the more affluent owners of properties abutting existing lines sued the elevateds and won, the Court of Appeals ruling they had been illegally deprived of “light, air and access.” The prospect of a series of heavy damage payments effectively halted all further elevated construction in built-up sections of Manhattan.

Apart from this victory, disgruntled citizens made little headway in attaining redress of grievances because of the elevateds’ structure of ownership. At first, the spurt of el building in New York had paralleled the outburst of railroad construction on the national level and involved many of the same players. Rival financiers, aware of the elevateds’ enormous potential, had taken control of them and engaged in the same free-for-alls that characterized rail warfare at the continental level. In New York City, however, the combatants were able to come together and obtain the monopoly control—and bonanza profits—that eluded them in the national arena.

The early contenders had leased their shares to a holding company, the Manhattan Elevated Railway Company. Jay Gould and Russell Sage swallowed it up in 1881 by driving its stock price down, then buying it up. They continued to use it as a financial plaything, much as Gould, Fisk, and Drew had done the Erie: heavily watering its stock; clearing millions on market manipulations. Some people kicked up a fuss, but Gould bought legislators, corrupted judges, and expanded his control, taking over the Third Avenue line too.

Private control and public interest clashed again in 1883, when the state legislature passed a bill to lower the monopoly’s fares from ten cents (and five cents at rush hour) to five cents all day. The bill was popular, but the Manhattan’s owners denounced it as an attack on property rights. They were backed by Drexel, Morgan, William H. Vanderbilt, and fifty other leading capitalists, who successfully petitioned Governor Cleveland to veto the offending legislation.

Gould and Morgan failed, however, in their effort to turn Battery Park into a switchyard and elevated loop. The intense anger generated by the Manhattan’s attempt at appropriating the only park accessible to the Lower East Side’s working-class families was compounded by the company’s maladroit dismissals of its opponents as tramps, rascals, and immigrants. Tammany Hall, usually in the Manhattan’s pocket, had to back away from it on this one, and the company abandoned its plan.

Popular protest might stop a Manhattan Company initiative but it couldn’t start one. By the late 1880s success had bred crowding, especially on the East Side lines—crowding that swelled to dangerous dimensions at rush hour. Station platforms got so jammed that passengers, unable to fight their way out of cars during the all-too-brief stops, were often carried one or two stations beyond their destination, while pickpockets fingered through their possessions. Given the absence of competition, and the presence of handsome dividends paid regularly on heavily watered stock, Gould, Sage, and Morgan had no incentive to relieve the miserable conditions, and so they didn’t.

If monopoly had drawbacks, so did competition, as became clear during the horse-car wars. The thirty-two rival street lines, whose routes often underlay the new elevated tracks, had been damaged by their overhead rivals but still made money. They did so by scrimping on upkeep (the cars were dirty and badly ventilated, their straw-strewn floors full of vermin). They also slashed labor costs (drivers and conductors worked sixteen-hour days, constantly exposed to the weather, for beggarly wages, conditions that would lead to violent labor upheavals in 1886). In addition, the lines still operated on perpetual franchises they had cozened out of compliant aldermen over the previous half century, for which they paid little or nothing to the city. Highly parochial and viciously competitive, each refused transfer privileges to its rivals. Journeys, accordingly, were badly splintered: traversing Manhattan at 14th Street required three car changes and four separate fares.

The horse-car wars spilled into municipal and state politics in the mid-1880s. Jacob Sharp, the wealthiest and shrewdest of the streetcar magnates, had been trying for thirty years to get a franchise allowing his Broadway and Seventh Avenue Railroad, which ran from 59th Street to Union Square, to use lower Broadway to reach the Battery. Though long blocked by powerful Broadway retailers and real estate princes like the Stewarts, Astors, and Goelets, by 1883 Sharp was close to having his way with a tractable state legislature. Suddenly a new rival emerged, the New York Cable Railway Company, composed of a group of businessmen that included Thomas Fortune Ryan, a Virginia-born, Irish-American stockbroker and protege of a Standard Oil partner. The cable interests, who planned to substitute horsepower for horses, also wanted a Broadway franchise.

In Albany, in 1884, Sharp’s lawyer, Francis Lynde Stetson (whom he shared with J. P. Morgan), introduced supportive legislation, while Sharp’s lobbyist, “Whisky” Halloran, disbursed two hundred thousand dollars to the legislators, handily outbribing the cable forces. Matters now shifted to the ever pliable Board of Aldermen, to whom Sharp gave half a million. To do battle effectively, Ryan added William Collins Whitney to his board of directors. Whitney, a dapper young attorney, was wise in the ways of local politics, having served as the city’s corporation counsel from 1875 to 1882, and been prominent among the Swallowtail Democrats. He was also well connected, having married Flora Payne, sister of his Yale roommate (and Standard Oil partner) Oliver Payne.

Whitney drew a group of Philadelphia millionaires into the Cable syndicate and easily topped Sharp’s bribe to the aldermen, coming up with $750,000, but stumbled in offering only half in cash and the rest in bonds in the new company; the politicos accepted Sharp’s all-cash incentive. Whitney recovered quickly, however. Announcing that had the franchise been sold at public auction he would have offered the city a million-dollar annual rental for it, he demanded an investigation of exactly why the aldermen were planning to give it away for a feeble forty thousand. In the ensuing uproar, an inquiry led to the indictment and conviction (or flight to Canada) of many of the now infamous “boodle” aldermen (their leader got nine years’ hard labor in Sing Sing). Sharp himself was sentenced to four years in the slammer, but the Court of Appeals reversed the verdict on technicalities and ordered a second trial, which Sharp avoided by his timely demise in 1888.

Whitney, Ryan, and the Philadelphians, left in possession of the field, consolidated their control over New York’s surface transit system. They organized a holding company, the Metropolitan Traction Company, at the suggestion of Francis Lynde Stetson and their chief legal counsel, Elihu Root. (Of him Whitney reputedly said: “I have had many lawyers who have told me what I cannot do; Mr. Root is the only lawyer who tells me how to do what I want to do.”) Using the techniques of national merger makers, the Metropolitan began buying, leasing, or conquering the independent horsecar companies, issuing vast amounts of heavily watered stock as it went. By 1897 it would control nearly every line in Manhattan.

As fast as they were acquired, Whitney and Ryan welded their roads into an integrated system. They instituted highly popular free transfers that finally made it possible to travel long distances for a nickel. They also understood that true rationalization required mechanization: the horse would have to go. By 1892 they had, at great expense, installed a cable line along Broadway. Powered by a steam engine in the basement of the handsome new nine-story Cable Building at Broadway and Houston, two endless steel strand loops ran, taut and humming, just below street level, one down to Bowling Green, the other up to 36th Street. Once a motorman gripped the cable, his streetcar was jerked along at thirty miles per hour, far faster than horses.

There were problems, however. Speed couldn’t be varied at corners, so cars whipped passengers around spots like Dead Man’s Curve at Union Square, gongs clanging wildly. Accidents—which were frequent—required stopping the belt, halting traffic all along the line. And when the forty-ton cables broke, which was often, they were not easy to replace. In short order the experiment would be declared a failure. Further problems emerged when George Gould, who succeeded to control of Manhattan Elevated when his father died in 1892, proceeded to declare war on the Metropolitan, a struggle whose consequences would reverberate into the next century. Most disturbing of all, while the street railway franchises proved enormously profitable to their owners, the city received virtually nothing by way of financial return, and speculators like Gould had no interest in promoting orderly and planned development in advance of existing settlement.

Still, for all their drawbacks, the city’s combined transport facilities helped weld Manhattan and its surrounding suburbs into an integrated regional economic unit. The Manhattan Elevated carried 75.6 million passengers in 1881; by 1891 it was conveying 196.7 million; and by the latter year, counting all means of travel, well over a million people poured into New York each day and flowed back home each night. Titans and typists, merchants and clerks, insurance men and accountants, storekeepers and shop-girls, lawyers and advertisers and journalists—they streamed, in their hundreds of thousands, across the Brooklyn Bridge to Brooklyn Heights, Bedford, and Bay Ridge; boarded the Staten Island ferry to New Brighton, where they caught trains out to Arrochar and Bowmans; clambered on cars at Grand Central that whisked them north to Yonkers, White Plains, and New Rochelle; ferried east to the Long Island Rail Road terminus at Hunter’s Point and west to Jersey for connections to Newark and Morristown. The great human tide ebbed to a hundred domestic destinations, regathered its energies, and was transported next morning back to the tall-tower workplaces, in time for the opening of yet another business day.