In the winter of 1883 Mrs. William Kissam Vanderbilt, born Alva Smith of Mobile, launched an assault on New York Society’s inner circle—still presided over by Caroline Astor and Ward McCallister—by announcing a fancy dress affair intended to eclipse the Patriarch’s Balls over which the reigning duo presided. The Vanderbilt fete would inaugurate the new château, at Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street, that she and her husband had commissioned from beaux-arts master Richard Morris Hunt, expressly to outclass the brownstones lower down the avenue.

Hunt had long been wishing New Yorkers would take an architectural leap forward. Now, with three million dollars at his command, he showed them how to do it, producing a palatial residence that, in the opinion of the Times, went way beyond anything “heretofore attempted in New York.” Well aware how mock-castles like Chambery and Chenonceaux had delighted the parvenu bankers and merchants of the Renaissance, Hunt erected an adaptation of Francis I’s sixteenth-century Château de Blois, filled it full of Renaissance and medieval furniture, tapestries, and armor, and had it ready for Alva’s ball in 1883.

The city’s elite gave itself over to a flurry of preparations. A hundred-plus dressmakers labored night and day for weeks. Groups of young women practiced “quadrilles”—complex dance presentations—among them Miss Caroline (Carrie) Astor and her friends, who planned to appear as pairs of stars. As daughter of the Queen of Society, she simply assumed, rashly, that her invitation was on the way.

It was not. As the magic night of March 26 approached, Mrs. Vanderbilt casually let it be known that no invitation would be forthcoming for the charming Miss Astor as, alas, she had never properly made her acquaintance, or that of her mother. The queen surrendered forthwith. A footman in Astor-blue livery was dispatched from the 34th Street mansion to deliver, a mile up Fifth Avenue, an engraved calling card to a servant in Vanderbilt-maroon livery. With her arrival in society thus duly certified, Alva Vanderbilt authorized a return delivery of the last of the twelve hundred invitations.

The affair, as every New York paper blared in front-page next-day stories, was the grandest social event to date in the city’s history. The barely completed halls and rooms, lined with roses, orchids, palm fronds, and bougainvillea, had been transformed into a tropical wonderland. The Louis XV salon was resplendent with Gobelin tapestries, and wainscoting ripped from old French châteaux. The triumphant hostess, costumed as a Renaissance princess, welcomed her equally gorgeously attired guests—including an array of Mary Stuarts, Marie Antoinettes, and Queen Elizabeths; her brother-in-law Cornelius was dressed as Louis XVI, but his wife, more au courant, came as The Electric Light. Alva presided happily over a spectacular dinner and a round of dancing. Many gave highest accolades to Mrs. S. S. Howland’s group for their Hobby-Horse Quadrille, in which the dancers appeared mounted on life-size model horses made of genuine hides, but Mrs. Vanderbilt perhaps warmed most to the graceful moves of Carrie Astor’s Star Quadrille.

By her grudging accommodation of Vanderbilts and other new Medici, Mrs. Astor preserved her hegemony for another decade. She became, in fact, something of a national institution. Over the next years, as the country followed with awe (or outrage) the shimmering doings of New York Society, Mrs. Astor’s verdicts and edicts as conveyed by the press—her remarks invariably couched in the third person—enthralled readers from coast to coast.

With the assistance of her chamberlain, Ward McCallister, she sustained, for a time, an unfortunately enlarged but still acceptably exclusive inner circle. In 1888 McCallister opined to a Tribune reporter that the core group was in fact small enough to fit comfortably into Mrs. Astor’s ballroom: “Why, there are only about 400 people in fashionable New York Society. If you go outside that number you strike people who are either not at ease in a ballroom or else make other people not at ease. See the point?” This pronunciamento created something of a stir and led to rampant speculation about who was (or was not) included on the gilded list of “the Four Hundred.” Finally, on the occasion of Mrs. Astor’s ball of February 1, 1892, McCallister issued a more precise inventory to the New York Times. It contained a mere 273 names, drawn mostly from the community of Patriarch’s Ball invitees.

Wealthy would-be socialites denounced this magisterial accounting with all the fervor of populists attacking railroad pools, and in a sense naming the Four Hundred was an attempt to create a Social Trust. But the ranks of the wealthy, augmented by millionaire arrivistes from around the nation, had swelled far beyond the bounds of Mrs. Astor’s ballroom. As in the larger economy, competitive forces proved too fierce to be contained by informal mechanisms that had worked for generations.

Mrs. Astor’s regime began to come unglued. Powerful rivals carped, mocked, and rejected her rule. Mrs. Burton Harrison, in 1895, said flat out: “I am an unbeliever in the body corporate which, for want of a better term has come to be popularly known as the Four Hundred of New York.” Fortunately another mechanism had evolved as a way to delineate a Society now clearly numbered in the thousands, not the hundreds.

Maurice M. Minton, an enterprising blueblood, had pointed the way by printing up his mother’s visiting list and merging it with another to form the Society-List and Club Register. In 1887 this example, and that of the recently introduced telephone directory, inspired Louis Keller to launch The Social Register. Keller, independently wealthy (though just barely), had his eye on more remunerative possibilities. With the support of friends at the Union and Calumet clubs, he assembled a list of nearly two thousand socially prominent names and printed it up as a handsome book with orange and black binding. To make it indispensable, he included addresses, telephone numbers, maiden names, wives’ names by previous marriages, clubs, colleges, places of summer residence, and names of yachts—everything one needed to keep up with old friends and screen potential new ones. (To get the lowdown on highbrow enemies, one could also turn, after 1885, to the pages of Town Topics, a Society scandal sheet that tattled about upcoming divorces and impending bankruptcies, using information secured from Fifth Avenue butlers and chambermaids. Fortunately one could forestall the display of dirty laundry by bribing the editor into discretion.)

With the advent of The Social Register, dictatorship gave way to an accommodating bureaucracy; now thousands could make the social grade. But with outspending one’s rivals the only definitive route to preeminence, a steady inflation in extravagance ensued as members of opposing cliques scrambled to convert Wall Street revenue into Fifth Avenue social standing. Dinner parties corkscrewed upward in lavishness—black pearls in oysters, cigars rolled in hundred-dollar bills, lackeys in knee breeches and powdered wigs. These glittering affairs attracted platoons of elegantly attired jewel thieves, whose takings were kept to a minimum by equally nattily dressed police detectives supplied by Inspector Byrnes, the same man whose Dead Line cordoned off Wall Street by day.

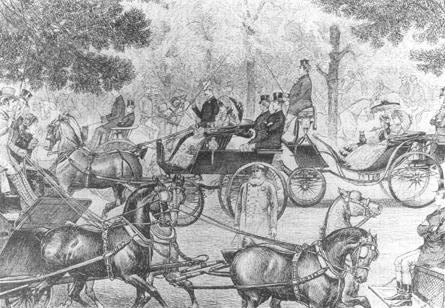

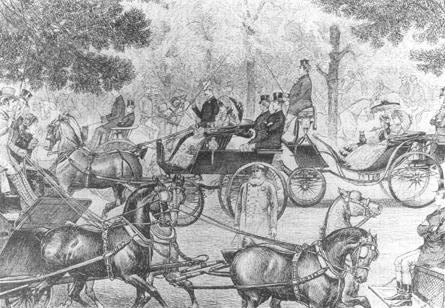

The Drive-Central Park-Four O’Clock, from Harper’s Weekly, May 19, 1883. Upper-class New Yorkers still regarded an afternoon drive in the park as an opportunity to see and be seen, but ascertaining who belonged to “society” was becoming increasingly difficult. (© Collection of The New-York Historical Society)

The social wars raged as fiercely on the male side, though here the front line ran through the opera house. Old-guard families had undergirded their position by cornering the market on Academy of Music boxes. From these seemingly secure perches, Bayards and Beekmans, Cuttings and Schuylers, and a few properly patinaed former upstarts like August Belmont had peered down contentedly on tycoons in the seats below. When William H. Vanderbilt offered a whopping thirty thousand dollars for a box in 1880, the old set snubbed him as they had his father, the Commodore, before him.

Vanderbilt embarked on a grand flanking movement. First he gathered together a formidably monied strike force, including many of the most powerful figures in the emerging corporate economy—his sons William Kissam and Cornelius II, J. P. Morgan, William Rockefeller, Jay Gould, William C. Whitney, George F. Baker—as well as some older patricians like Ogden Goelet, Adrian Iselin, and William Rhinelander. Then Vanderbilt announced they would construct a new opera house, as grand as those of Milan and Vienna, and eclipse the 14th Street bastion forevermore.

Belmont and company panicked and offered to add twenty-six boxes to the Academy’s existing eighteen, but it was too late. Way uptown, at Broadway and 39th Street, a mammoth edifice slowly took shape, the grandly named Metropolitan Opera House, capable of seating over thirty-six hundred people, and accommodating wealthy patrons in seventy opulent boxes. On opening night, October 22, 1883, with Faust as the inaugural performance, these were packed with opera lovers whose collective worth was estimated at $540 million. “The Goulds and the Vanderbilts and people of that ilk,” wrote the New York Dramatic Mirror, “perfumed the air with the odor of crisp greenbacks.”

The Metropolitan was an instant triumph. The doomed Academy of Music hung on gamely a few more years, then folded with an announcement from its manager that “I cannot fight Wall Street.” Musically its early years were somewhat shakier. To fill the huge hall, the Metropolitan called on Leopold Damrosch, a devout Wagnerian. Damrosch devoted the 1884 season almost entirely to German opera. Singers were imported from Bayreuth. This appealed to the city’s massive German population, but boxholders loathed the new music, couldn’t see one another’s finery in the Wagnerian gloom, and bustled and gabbled throughout the performances. When rebuked by the Germans below, the directors maintained that the stockholders had a perfect right to disturb whomever they wished. Conductor Anton Seidl, who had assisted Wagner at Bayreuth, replaced Damrosch on his death in 1885 and maintained the German program for several more years, until a full-scale revolt brought back Italian and French opera.

In the symphonic world, musically inclined industrialists and financiers were having problems of a different sort with the New York Philharmonic. The old German cooperative presented only half a dozen concerts each year. As the orchestra couldn’t guarantee members full time work, they spent most of their time playing at balls and dances; hence their performances were less than highly polished, though much improved after Theodore Thomas was taken on as conductor. Neither their less than professional standards nor traditional repertoire bothered old-fashioned elites, but both failed to satisfy new tycoons. A capitalist combine including Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Morgan, and Carnegie underwrote a rival, the New York Symphony Orchestra (1878), another Leopold Damrosch project. Orchestra war ensued. In one notable sally Damrosch stole the American premiere of Brahms’s First Symphony from under Thomas’s nose.

On Leopold’s death in 1885, his son Walter succeeded to Symphony leadership, and the younger Damrosch convinced Andrew Carnegie that what the group needed was a permanent home—the Metropolitan Opera House being inadequate for orchestral performances. Carnegie agreed to support construction of a first-class concert hall. On May 5, 1891, a vaguely Italian Renaissance structure—including the velvet-lined, acoustically superb Music Hall, as it was then known—opened at another untraditionally uptown venue, Seventh Avenue and 57th Street. Nestled in their boxes, subscribers Whitney, Rockefeller, Frick, and, of course, Carnegie himself heard Episcopal Bishop Henry Codman Potter say that while in European countries culture often depended on state patronage, “it is a happy omen for New York that a single individual can do so princely a thing.” Then they and their guest of honor, Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky—the symphonic giant had been lured by Carnegie with a fee of twenty-five hundred dollars—listened to Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Orchestra inaugurate a five-day festival.

New money thrust its way into the world of men’s clubs with equal dispatch. In this case it was the Union Club—the city’s most prestigious—that gave offense. Patrician members had opened its exclusive doors just enough to allow a few newly monied to squeeze inside, but the rate of access was far too slow for those clamoring to be admitted. This time it was J. P. Morgan who assembled the group of refusés. Again, a new edifice was built, a regally scaled Italianate structure. Again, the newcomer was grandly titled the Metropolitan. And again, its backers situated the building, which opened in 1894, far uptown from the center of established clubdom—at Fifth Avenue and 60th Street.

Hunt’s château for the Vanderbilts proved an epochal success. Previous elites had rejected efforts, by A. T. Stewart and Leonard Jerome, to break the brownstone mold. But the eighties’ elite loved the Vanderbilt mansion’s scale, materials, and ornate sensuousness. They hailed it as a liberation from what their own Edith Wharton would call New York’s “mean monotonous streets,” lined with buildings “of a desperate uniformity of style” and a “universal chocolate-coloured coating of the most hideous stone ever quarried.”

Not all the elite was swept off its feet, to be sure. In 1882 J. P. Morgan was making a decent half million a year and could well have afforded something ostentatious. But Morgan despised fashion and vulgar display (except in yachts) and opted for a brownstone at Madison and 36th, in the no longer cutting-edge Murray Hill. And when the staunchly Baptist John D. Rockefeller arrived in town, he too settled in a brownstone, albeit one within blocks of the Vanderbilt château.

Nevertheless, Hunt would be kept busy until the day he died fashioning urban mansions for the rich, and their homes away from home as well. During the late 1880s and 1890s—as the elite fled Saratoga for Newport—Hunt constructed colossal summer places for them, like the Marble House for William Kissam Vanderbilt, and the Breakers for his brother Cornelius II. Indeed so great was the flow of commissions from avid haute bourgeois househunters that it begat a whole new generation of New York architects, of whom perhaps the most influential were Stanford White and Charles McKim.

McKim studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1867-70, came back to work in H. H. Richardson’s New York office, then drifted out of Richardson’s Romanesque orbit into that of Hunt’s Renaissance. When the Vanderbilt 52nd Street château went up, it seized his imagination; he got into the habit, he later recalled, of walking up Fifth Avenue late at night to admire it and “always slept better for enjoying the sight.” But even during the 1870s McKim had begun designing town houses in what was coming to be called the Queen Anne style, based loosely on English Renaissance sources. He also came to love the architecture of England’s American colonies—McKim was among the first to appreciate eighteenth-century vernacular buildings—and he held in high regard the civic decorum and classical orderliness of New York’s Federal structures.

Stanford White traveled a similar trajectory. Born in New York in 1853, he grew up in the city’s artistic and reform community. His father, Richard Gant White, was a cosmopolitan essayist who penned articles on music, art, literature, the stage, and English life and manners for the Galaxy, Nation, and Century magazines. The elder White was also a friend of Calvert Vaux and Frederick Olmsted. It was through Olmsted that young White got an apprenticeship in Richardson’s firm in 1872, replacing McKim, who had opened his own firm in collaboration with William Mead. Seven years later, White joined the other two, and the trio of McKim, Mead, and White would dominate New York’s architectural scene for the next generation.

The firm, a brilliant combination of talents, was described as a vessel of which McKim was the hull, White the sails, and Mead the rudder and anchor. McKim, who styled himself “Bramante,” produced restrained, fine designs. Mead organized the staff along the same lines as the other corporate and professional headquarters then going up in Manhattan, and by 1892, with 120 draftsmen, it was the largest architectural office in the world. White provided drama and flair—both in his work and his personal life—and brought in most clients.

White, the self-styled Benvenuto Cellini of the profession, was indeed a renaissance man. Apart from his architectural work, he painted, designed furniture and jewelry, collected antiques. He was also a man-about-town—he loved making a grand entrance at the opera in cape and red mustache—and was a vigorous, not to say ubiquitous clubman. His various memberships allowed him to mingle with moguls and pull in commissions from Knickerbockers and nouveaux riches alike. The firm’s list of clients included Astors, Fishes, Goelets, Morgans, Pulitzers, Stuyvesants, Vanderbilts, and Villards.

McKim, Mead, and White didn’t monopolize the field; they shared it with a formidable array of practitioners—including William Ware, Richard Upjohn, James Renwick, LeBrun, and others who formed, in 1881, the Architectural League of New York, seeking to elevate their skills to Ecole des Beaux Arts standards. Devoted to European models, many used books of photographs they had snapped on their grand tours to convince clients of the accuracy of their imitations. No stylistic consensus emerged; rather the new generation ransacked all European history.

The Vanderbilt-Hunt collaboration inspired, and the eighties’ upturn made feasible, a building boom in town houses. Even the mid-1880s recession spurred construction, as investors frightened by chaos in the stock market shifted their capital into real estate. Soon upper Fifth was chock-a-block with millionaires—Harry Payne Whitney, Charles Harkness, Jay Gould, Collis P. Huntington, Benjamin Altman, Robert Goelet, Solomon Guggenheim, Russell Sage—and even the Astors, followers now rather than leaders, abandoned lower Fifth. The queen had Hunt build her a white French Renaissance palace at 65th Street, where she lived out the closing years of her reign. William Waldorf Astor sidled northward to a cream-colored Touraine château at the corner of 56th, three blocks south of the great complex of luxury skyscraper hotels clustered around 59th that included the Plaza, the Savoy, and his own seventeen-story New Netherland Hotel.

Fifth Avenue north from 65th Street, 1898. The château that Hunt designed for Caroline Astor stands on the near corner, anchoring a line of mansions that stretches uptown as far as the eye can see. (© Museum of the City of New York)

Some plutocrats pressed slightly eastward, to Madison Avenue, though not so far as the newly (1888) and misleadingly renamed “Park” Avenue, still fatally blemished by ventilation holes belching smoke and steam from the trains below. In 1882 McKim, Mead, and White started on a complex—between 50th and 51st, just behind the recently opened St. Patrick’s Cathedral—of six town houses grouped around a court. Their client, railroader Henry Villard, got a monumental Italian Renaissance structure, based on the Cancelleria in Rome, outwardly austere, richly embellished on the inside. Unfortunately for Villard, as the buildings were going up he was suffering career reverses. During the 1884 panic he moved into the unfinished house, hoping to save on hotel bills, but angry crowds besieged him there, as they hunted down Ward and Fish elsewhere in the city. After a few weeks Villard moved out, never to return, and in 1886 he sold the complex to Tribune publisher Whitelaw Reid.

The Seventh Regiment’s new armory at 66th Street facilitated elite expansion into heretofore drowsy Lenox Hill. The French medieval-style fortress (with elegant interior for the unit’s social functions designed by White and Louis Comfort Tiffany) guarded against the concentration of working-class Germans and Irish stretching from Third Avenue down to the East River, providing a sense of security for the northward-streaming rich. Elegant mansions went up, interspersed with rows of individualized Queen Anne town houses sporting facades with square and polygonal bows and bays, and oriels of every shape.

Lenox Hill remained Society’s outer periphery until the 1890s, when mansions advanced up Fifth to Prospect Hill, encouraged by the new Eighth Regiment Armory (1894) on Park Avenue between 94th and 95th, which bulwarked the area against laboring masses to the east. Even so, only a handful of the wealthy—chiefly Germans like the Rupperts, Untermeyers, and Ehrets—braved such proximity to the tenement world.

Not everyone in Châteaux Country could afford a grand-scale mansion, and some who could afford luxurious-but-not-magnificent accommodations found the cooperative apartment house an appealing alternative. In 1880 Philip G. Hubert, a French emigré architect, organized his first Hubert Home Club, a device for allowing “gentlemen of congenial tastes, and occupying the same social positions in life,” to buy shares in a joint stock company, which then bought land and erected an apartment building. Each cooperator got a perpetual lease to an apartment, its size dependent on how much he put in (costs ranged from ten to fifty thousand dollars). Each was assessed a share of the combined operating expenses: taxes and insurance, light and heat, janitors and elevator boys. Each got the right to approve, together with other leaseholders, the mere tenants to whom some suites were rented in order to pay off the mortgage.

The cooperative apartments of the 1880s, as well as those raised wholly by speculators for rental purposes, were a cut above the French Flats of the previous generation. They were huge—eight to twelve stories in height, as tall as or taller than most downtown skyscrapers. They were elaborate, châteauesque, awash in turrets and gables. The suites, which could include as many as twenty rooms, came with the parlors and reception rooms that guaranteed cachet. They offered all sorts of conveniences, grand public spaces and courtyards, dining facilities, and building staffs that, as Harper’s noted in 1882, allowed families to make do with half the usual number of servants.

Luxury apartments tended to cluster in or near already affluent areas and to bear distinguished-sounding names. There was the Gramercy (1883) at Gramercy Park, the Berkshire (1883) on Madison at 52nd behind St. Patrick’s, and the Chelsea (Hubert’s most popular project), an immense, red-bricked, multigabled cooperative on West 23rd near Seventh Avenue.

The densest concentration, however, lay just south of Central Park. Hubert’s first Home Club, the Rembrandt, went up on West 57th Street in 1882, next to the future site of Carnegie Hall. Nearby were the Plaza at 59th Street, the Osborne Apartments at Seventh and 57th, and the grandest of them all, completed in 1885, the Central Park Apartments (a.k.a. the Navarro Flats, after their builder) at Seventh and 59th. From a distance the Navarro appeared a single Moorish mass of turrets and dormers. In fact it consisted of eight ten-story personalized towers, each with its own entrance and name (Granada, Valencia, etc., hence yet another nickname, the Spanish Flats), all of them wrapped around a tremendous courtyard filled with trees, flowers, and fountains. Each apartment had its own floor; most had views of Central Park. It was by all accounts the largest and most elegant apartment house in the world.

The Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide called these behemoths “tenements of the rich,” and with the cost of ground and building easily topping a million dollars, most cooperative shareholders were among the city’s most affluent. But very well off professionals and managers could handle the rental prices: a ten-room in the Spanish Flats could be had for eighteen hundred dollars a year, and the Chelsea, which rented out thirty of its ninety apartments, embraced an even wider spectrum of tenants.

There was, however, another alternative for venturesome members of the “comfortable bourgeoisie”: the “American Belgravia” of the Upper West Side. In 1879 Edward S. Clark, the Singer Sewing Machine magnate now branching out into real estate development, read his paper entitled “The City of the Future” to members of the West Side Association. Clark argued that pulling the right sorts of people northward required a mix of single-family homes and some truly striking apartment houses, where “the principle of economic combination should be employed to the greatest possible extent.”

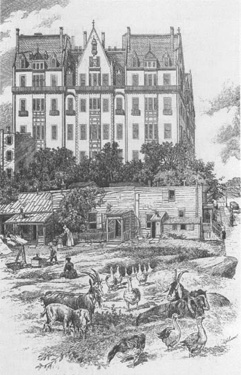

Clark delivered the latter in grand fashion in his Dakota Apartments (1884). “Dakota” was synonymous with distance and wealth—gold having been discovered in the far-off territories in the 1870s—and Clark’s monumental Renaissance palace, looming over Central Park at 72nd Street in splendid isolation, embodied both. The ninestory structure by Henry Hardenbergh boasted a cour d’honneur manned by a concierge and an interior courtyard large enough to accommodate a carriage turnaround. Occupants of the fifty-eight suites (which ranged from four to twenty rooms) had access to hotel-style amenities, a wine cellar, a large dining room for private parties, and additional rooms under the mansard roof for Irish cooks and coachmen. It was fully rented by the day of its completion, peopled not with millionaires or fashionables (not a single tenant made the Social Register in 1887) but prosperous professionals and businessmen, many of them associated with the arts.

The Dakota Apartments, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 7, 1889. As affluent residents flocked to the West Side, the shanties quickly disappeared. (General Research. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

The Dakota fixed the West Side’s character not only in spawning a rash of western-named buildings—the Wyoming, Yosemite, Nevada, and Montana—but in helping draw the affluent to town houses that went up along the avenues (some with suitably upgraded names: Eleventh became West End Avenue in 1880; Eighth became Central Park West in 1883). No chocolate brownstone uniformity here, but rather individualized, eclectic, historical styles, jumbling together Jacobean, French Gothic, and Dutch Renaissance. Indeed McKim, Mead, and White touched off a Dutch Colonial revival in 1885, with their row houses on West End and 83rd, and soon the area resembled a new New Amsterdam. Better still, by 1893 (King’s Handbook of New York City reported)—while the Four Hundred were not in evidence—the West End locale had become “to a certain extent fashionable,” so much so that “even society countenances it.”

To decorate their interiors—the term “interior decoration” dates from the late 1870s—the wealthy patronized local artists as well as local architects, commissioning craftsmen to design walls, windows, and woodwork. The flood of orders fostered formation of a small, interlocking network of artists whose work gave luster to the city’s, and the elite’s, cultural reputation. Indeed the rich generated such a swirl of activity that they half convinced themselves, in the words of one artist, “that the days of the Italian Renaissance were revived on Manhattan Island.”

The Vanderbilts, again, were among the foremost patrons, with Cornelius II assembling a platoon of artists to decorate his mansion. For glasswork he turned to John La Farge. The New York-born son of a cultivated French family, La Farge had studied in France, where he’d been inspired by impressionists, Japanese prints, and stained glass. On his return he invented (and patented) an opalescent glass and produced fabulous windows and ceiling panels. For sculptural details Cornelius turned to La Farge’s friend and collaborator, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Son of a French father and Irish mother, Saint-Gaudens too was brought up in New York, where he studied at Cooper Institute before attending the Ecole des Beaux Arts, and now provided Vanderbilt with Renaissance ornamental motifs.

Vanderbilt also employed the firm of Associated Artists, formed in 1879 by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Tiffany’s atelier was a mix of Renaissance workshop and corporate headquarters. Each partner had his own department—fabrics and wallpapers, carving and wood decoration, textiles and embroideries—the whole presided over by the master. Tiffany also ran the glass department and, like La Farge, patented novel production processes. These craftsmen, following the path of contemporary professionals, formed their own organizations (like the Society of Decorative Art, 1877), their own social groups (like the Tile Club, 1877), and their own schools and periodicals.

In fact, however, Manhattan Medici imported the bulk of their artwork from Europe, turning to professional art consultants to certify their purchases. Among the most prestigious were Joseph and Henry Duveen, English-based importers of antique porcelain. Sensing a lucrative market opening up in New York, the Duveens started a branch operation in Manhattan. Henry brought over high-quality porcelain, silver, tiles, and tables, and business began to click the day Stanford White wandered into the store. White introduced Duveen to his wealthy friends, notably J. P. Morgan, then in the market for tapestries to cover the vast walls of his new mansion and furniture to cover its floors. Happily for all concerned, rich aristocrats were junking tapestries left and right, in favor of William Morris wallpaper, and clearing out their old armor and furniture. Joel stripped and shipped noble interiors to Henry’s Fifth Avenue offices, and Henry cultivated new clients, like department store magnate Benjamin Altman, whom he began assisting in 1888.

In the world of painting and sculpture, would-be collectors had, until the mid-1880s, turned to local dealers like Michael Knoedler, Jean-Baptiste Goupil, and Samuel P. Avery, whose styles tended toward the private and personal. The boom years changed all this, generating a vigorous and highly visible art market pioneered by Thomas Kirby, an art auctioneer of long standing. Kirby’s profession, like advertising, had a somewhat shady reputation, which may account for his invariably impeccable appearance: wing collar, cutaway morning suit, and clipped, pointed imperial beard. In 1883 Kirby joined forces with two men who ran an art gallery on the south side of Madison Square, transforming it into the American Art Association (AAA), a salon “for the Encouragement and Promotion of American art.” When his 1887 sale of the late A. T. Stewart’s collection fetched over half a million dollars, the AAA was firmly established as the city’s foremost marketplace for sales of fine art, antiques, rare books, and jewels.

For all Kirby’s talk about the “Promotion of American art,” however, he and his buyers were fixated on Europe. But within those parameters he was willing to take some chances. In 1886 the AAA arranged to have the famous dealer Paul Durand-Ruel send over 289 works of modern French art. The first massive French impressionist show in the United States included oils by Renoir, Manet, Degas, and Pissaro, among many others. The New York press was underwhelmed—“Is this Art?” asked the Times—but the perceptive Durand-Ruel found New Yorkers were far more open to his painters than Parisians had been at first, and the following year he opened his own gallery at 297 Fifth. Impressionist collectors like Louisine and Henry Osborne Havemeyer—awash in Sugar Trust money—soon proved him right, and New York became established as modern art’s portal to America.

In March 1880 President Hayes joined frock-coated trustees, and their wives in silk dresses, in dedicating the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new building. To reach the entrance of Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould’s barnlike, red brick structure, guests had to troop along a boardwalk that ran from Fifth Avenue to the main entrance on the building’s west side. Once they were settled, Joseph C. Choate, one of New York’s leading corporate attorneys, addressed the distinguished conclave.

He stressed the civic purposes of the new museum. It would not, as in Europe, be a plaything for wealthy connoisseurs—a “mere cabinet of curiosities which should serve to kill time for the idle”—but rather a democratic institution that by its “diffusion of a knowledge of art in its higher forms of beauty would tend directly to humanize, to educate and refine a practical and laborious people.”

Choate also pointed to the benefits awaiting the museum’s patrons. New York’s rich could gain personal immortality by converting some of their fortunes—transient and perishable in any event—into a more permanent legacy. Wall Street, he enthused, should “convert pork into porcelain, grain and produce into priceless pottery, the rude ores of commerce into sculptured marble, and railroad shares and mining stocks—things which perish without the using, and which in the next financial panic shall surely shrivel like parched scrolls—into the glorified canvas of the world’s masters, that shall adorn these walls for centuries.”

Choate’s stress on public benefits was politic. The museum, though privately owned, had been built with municipal largesse, including the parcel of Central Park on which it sat and the half-million dollars that had paid for its construction. But while director Luigi Cesnola believed the museum a source of “civilizing, refining, and ennobling influences,” the Tribune suggested that “from the very beginning it has been an exclusive social toy, not a great instrument of education.”

The Met had developed a snobbish reputation, in large part because most of the public couldn’t get in. On Sunday, the one day the purported audience of working-class citizens could attend, the doors were shut fast by a board of trustees dominated by stoutly Sabbatarian Presbyterians. As early as 1881 ten thousand petitioned the Department of Parks to force the Met to open on Sundays, an appeal supported by almost every paper in the city and by reformers who argued that the museum could aid the “struggle against gigantic vices” by allowing access to its uplifting precincts. The Met trustees held firm for a decade, caving in only when the state legislature threatened to block a proposed North Wing expansion. On the first open Sunday, May 31, 1891, twelve thousand came, and Sunday remained the institution’s most popular day ever after.

The museum nevertheless continued to cultivate wealthy art collectors, whose donations were a crucial source of accessions, and their artistic preferences shaped the museum’s collections. William H. Vanderbilt liked sugary canvases of landscapes, allegories, and scenes of the wealthy at leisure, like the aptly titled work by Erskine Nicol called Looking for a Safe Investment. Henry Gudron Marquand, who had made a fortune in real estate, banking, and railroading, assembled an important collection of Van Dycks, Rembrandts, Hals, and Vermeers, which, when lent to the Met in 1888, instantly put the institution in the forefront of American museums. Most art that reached the museum was safely conventional in style and subject. At one point a group of young turk trustees pushed for including some of the impressionists, but the revolt on behalf of “advanced canvases” was put down by an old guard led by Marquand, Dodge, Rhinelander, and (trustee since 1888) J. P. Morgan.

So far as local painters were concerned, the Manhattan Medici were at best lukewarm patrons. Director Cesnola dismissed complaints by New York artists unrepresented in the Metropolitan as crassly self-interested men who wanted the museum to be “a kind of marketplace where their works were to be sold at exorbitant prices and permanently exhibited as their professional advertisement.” This dismissal—a sharp contrast to their underwriting of decorative artists—was the odder because many youthful painters were producing just the kind of academic work that moguls seemed to favor. Yet the elite passed them by, preferring to patronize the London-based John Singer Sargeant, who in 1887 began painting full-blown portraits in New York City.

The truly unconventional did worst of all. One of the founding members of the Society of American Artists—a breakaway group from the National Academy of Design—was Albert Pinkham Ryder, a red-bearded, dreamy-eyed visionary. Ryder had begun his art career in the customary way, studying at the National Academy and setting up a studio near Washington Square. But after 1880 he was drawn to New York’s “nightbird” tradition, best exemplified by Poe, and his canvases veered toward the romantic, the mysterious, even the sinister. He loved to walk around the city at night, soaking up the effects of moonlight on clouds, though his work never dealt with metropolitan “reality” in any but the most mediated way. Ryder was ignored by critics and public alike.

In the mid-1870s, as de facto editor of the New York Sketch Book of Architecture, Charles McKim reprinted images of old Manhattan treasures, especially Mangin and McComb’s City Hall, which he called the “most admirable public building in the city.” In revaluing the city’s built remains, McKim helped fashion a turn toward the past, one that particularly appealed to old Knickerbocker and mercantile families who couldn’t muster the financial resources for the social arms race. “Life here,” rued Frederic J. DePeyster in the early 1890s, “has become so exhausting and so expensive that but few of those whose birth or education fit them to adorn any gathering have either strength or wealth enough to go at the headlong pace of that gilded band of immigrants and natives, ‘The Four Hundred.’”

There were, of course, many old-timers who could well afford to “go the pace.” Descendants of Knickerbockers and merchant princes who owned large amounts of Manhattan real estate had profited from the city’s transformation into a corporate headquarters. Others had invested wisely in the new industrials. When the Tribune Monthly published a list of millionaires in 1892, a respectable one-fifth of the names belonged to antebellum families: Livingstons, Schermerhorns, Rhinelanders, Stuyvesants, Astors, Beekmans, DePeysters, Morrises, and Van Rensselaers. Even more tellingly, 60 percent of the leaders of New York’s national corporations, investment banks, and railroads were descendants of old-monied families.

Still, out of penury or principle, many of those caught up in the status struggle emphasized what they had and upstarts didn’t— a pedigree. Ever since the confrontation in the 1820s between Knickerbockers and New Englanders, bluebloods at bay had organized social bastions based not on wealth, or even accomplishment, but on heredity. Now the St. Nicholas Society (1835) and the Knickerbocker Club (1871) were joined by a host of others, like the Society of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York (1884) and the Holland Society (1885), which required a colonial ancestor in each member’s closet. As Knickerbocker Robert B. Roosevelt told the Holland Society men in 1886, theirs was a haven for the “old residents of New York”—a race, added William D. DeWitt, that was “being outnumbered and overrun in its own land.”

Soon such sanctuaries abounded, and members snuggled into their pedigrees, hunted up coats of arms at the Genealogical Society, and burnished their forebears’ image the better to shine by reflected glory. Patrician women—like those in the New York chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (organized at Sherry’s in 1891)—reenacted colonial teas using their ancestors’ cups and wearing their great-grandmothers’ gowns.

Some ancestral societies, however, adopted a more activist stance toward New York’s history. Noting (with Frederic DePeyster) that “the mighty city of today knows little or nothing of our traditions,” the old guard turned to publicly promoting them. They placed tablets at historic sites, raised commemorative statues in public parks, and in 1889 began publishing Old New York, a journal of city history and antiquities. Documentary reclamation projects got underway as well: in 1891 the state legislature authorized verbatim republication of the colonial laws, and in 1894 the Society of Iconophiles set out to publish both contemporary and facsimiles of early views of New York.

A string of city histories appeared, some in the elegiac vein pioneered by Abram Dayton’s Last Days of Knickerbocker New York (1882), others works of substantial scholarship, much though not all of it written by women. Martha Lamb’s History of the City of New York was published beginning in 1877; in 1884, Benson J. Lossing published his two-volume History of New York City; and Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer penned historical essays for Century Magazine, which prefigured her later two-volume study of the seventeenth-century city.

Many female historians stuck to the history of women’s sphere, writing, as had antebellum scribbling novelists, about home and hearth. Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt declared, in her Social History of Flatbush (1880), that “as a woman, I have inclined to the social side of life, and have endeavored to record the changes which time has made among the people in their homes and at the fireside.” Alice Morse Earle, a member of the Society of the Colonial Dames, did the same in Colonial Days in Old New York (1896). And the redoubtable May King Van Rensselaer made clear, in The Goede Vrouw of Mana-ha-ta at Home and in Society, 1609—1760 (1898), that while “history is generally written by men, who dwell on politics, wars, and the exploits of their sex,” she would chronicle “household affairs, women’s influence, social customs and manners.”

Old-monied men and women also embraced historic preservation, a decidedly un-New York sort of enterprise. Provoked by the latest spasm of vanishing churches, inns, and houses, preservationists rallied in 1889 to save Alexander Hamilton’s Grange by shifting it to a new location. And in 1892, when the 1763 Rhinelander Sugar House at Duane and Rose was demolished, a portion of the building was reerected, together with an inscription, alongside the old Van Cortlandt house up in the Bronx.

Their most heroic campaign helped save City Hall. By 1893 efforts to tear it down and build anew had gotten as far as an architectural competition for its replacement. In 1894 the Sons of the American Revolution published a piece by Andrew Haswell Green calling for “The Preservation of the Historic City Hall of New York,” and that year Green and Frederic J. DePeyster organized what would become the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society. Harper’s ratified the effectiveness of their intensive protests when it declared: “The majority of cultivated persons in New York would regard the demolition of City Hall not only as a municipal calamity, but as an act of vandalism.”

Old-guard New Yorkers did not stand alone on the ramparts of history. Fashionable members of Châteaux Society also exhibited a penchant for the bygone days of pre-Reformation and Renaissance opulence, and some tycoons responded to the Knickerbockers’ lineage challenge by purchasing instant pedigrees through marriage into titled European families. Clara, adopted daughter of railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington, wed Prince von Hatzfeld Wildenburg in 1889. Florence, offspring of corporate lawyer John H. Davis, became the second marquise of Dufferin and Ava in 1892. And in 1895 Pauline, daughter of horsecar magnate William C. Whitney, became the baroness Queensborough.

Dukedoms didn’t come cheap. Impecunious earls insisted on a quid pro quo for their bloodline transfusions. It cost $5.5 million to ransom the daughter of the despised Jay Gould into respectability. Even this outlay paled before the transatlantic exchange of assets arranged between Alva and William Kissam Yanderbilt and the ninth duke of Marlborough. In 1895 they virtually bludgeoned their daughter, Consuelo, to the St. Thomas altar and gave her away in the most spectacular nuptials in New York social annals. “Gave” is perhaps not the right word, given that compensation for His Grace included fifty thousand shares of Beech Creek Railway, the rehabilitation and maintenance of Blenheim Palace, and the construction of Sutherland House in London—an eventual Vanderbilt outlay of over ten million dollars.

In the right circumstances, the newly monied could be drawn into celebrating local history as well. In 1874 the country had kicked off a series of centennial commemorations by honoring the Continental Congress’s first meeting in Philadelphia. By 1883 it was New York’s turn. To celebrate the hundredth anniversary of Britain’s exodus from the city, the metropolis revived Evacuation Day—the local holiday that; apart from a brief Tammany-inspired revival in the mid-1860s, had been pretty much supplanted by Independence Day before the Civil War. New Yorkers with Revolutionary ancestry claimed a special role in these ceremonies, but William Astor and William Vanderbilt helped finance the festivities too. The culmination of the event was the unveiling of John Quincy Adams Ward’s twice-life-size statue of Washington on the front steps of the Sub-Treasury, site of Federal Hall. Ward, unusually, depicted Washington as civilian gentleman rather than martial equestrian, a decision that pleased the bankers and brokers over whose Wall Street community the genteel bronze Washington would now preside.

Evacuation Day redivivus proved mere prelude to a full-blown reenactment, six years later, of Washington’s inauguration in 1789. The old-guard New York Historical Society and New York Society of the Sons of the Revolution again tried to preempt the event, but by now the wider New York bourgeoisie had developed a passion for local history almost as strong as their romance with the Renaissance and the world of Marie Antoinette. The Chamber of Commerce demanded a role in the planning, as did many others—so many that in 1887 two hundred interested parties merged in an ecumenical Committee of Citizens, which proceeded to fashion a glittering three-day event honoring the Court of Washington and the Court of Contemporary New York.

The pageantry began on April 29, 1889, with the arrival of President Benjamin Harrison from Washington City. He reprised his predecessor’s cross-harbor voyage from New Jersey on a replica of the original barge, crewed by shipmasters from the New York Marine Society, the organization that had conducted Washington to Manhattan a century earlier. Landfall was followed by a march up Wall Street, a formal reception for four thousand of New York’s business and professional elite at the Lawyers’ Club, and a more intimate French feast for sixty at Café Savarin, whose souvenir menu listed the names of the City Council of yore (noting pointedly the absence of “Divvers, Flynns or Sheas”).

Evening brought seven thousand guests to the Metropolitan Opera House for a grand Centennial Ball. Ladies and gentlemen, selected by Ward McCallister after a careful genealogical search, opened the gala by doing a Centennial Quadrille in colonial costume. To no one’s surprise, Mrs. William Astor led the dance, brilliant in diamonds and a Worth creation. Some women did wear gowns “after the colonial period,” but far more New York aristocrats favored apparel from the courts of Louis XV and XVI.

Not all the events were so exclusive. A reenactment of the swearing-in, which featured an address by New York Central’s Chauncey Depew, attracted huge numbers of spectators, as did the Grand Military Parade. An estimated million people, vast numbers of whom had poured in by excursion trains, watched as fifty thousand members of various state militias marched from Wall Street up to the heart of Châteaux Country at 59th and Fifth. Finally, at the tail end of the events, a second float-filled parade allowed participation by those so far restricted to spectating. Immigrant societies, butchers in knee breeches brandishing sausages, plasterers tossing new-made busts of Washington to the crowd, firemen, policemen, and the sachems of Tammany Hall predominated here, though the accent remained aristocratic.

In the end, the colonial revival provided a way for new money to bow to old money’s values, while old money acknowledged newcomers’ superior resources. Perhaps appropriately, its most lasting legacy proved to be the practice of collecting “antiques”—a craze for amassing historical commodities having been ignited by the six-week-long Centennial Loan Exhibition of old gold and silver plate arranged by a Metropolitan Museum curator at the Metropolitan Opera House. New money also made its way into the Historical Society. While it was Rufus King’s grandson who presided over the sanctum for much of this era, the drive for a costly new building, planned for Central Park West between 76th and 77th, made the participation of Cornelius Vanderbilt and J. P. Morgan particularly welcome.

Upper-class New Yorkers had other settings—boarding schools, country clubs, exclusive resorts, elite universities, and Protestant churches—in which blood and money could forge a common culture. In the 1880s and 1890s, these elite institutions displayed both a new cosmopolitanism and a new parochialism, the first evidenced by a willingness to mix and mingle with provincial and professional elites, the second by the rise of anti-Semitism.

Magnates and Knickerbockers alike sent their sons to exclusive, usually Episcopalian private schools. They didn’t mind that nearly all the influential prep schools of the 1880s and 1890s were more in Boston’s than New York’s cultural orbit. Nor did they object to their sons mixing with wealthy young men, from around the country, who would one day would join with them in owning and managing the corporate economy. Together they learned classics, sports, and social graces, while developing the habits of command and taste for public service that would become the hallmarks of their class.

From boarding school the elite-in-training headed on to college. Columbia remained a patrician citadel, with old-line mercantile supporters like the Lows and Schermerhorns joined by industrialists and financiers, but increasingly both elite branches found the college too parochial. Roosevelts and Fishes, who had for generations sent their sons to Columbia and served as its trustees, now opted for Harvard or Princeton or Yale, and Morgans and Vanderbilts followed in their footsteps.

Like prep schools, colleges brought New Yorkers into fruitful contact with youthful members of the propertied and professional classes from around the nation. Elite scions bonded in Greek-letter fraternities like Delta Kappa Epsilon (both Theodore Roosevelt and J. P. Morgan were members). This facilitated formation of “old boy” alumni networks that would help bind together a class capable of withstanding the centrifugal forces of competitive capitalism. Ivy League schools also served as socializing and recruiting grounds for senior subalterns, the managers who would run the banks, mercantile houses, and industrial corporations, along with leading lawyers, architects, and physicians.

An “old girl” network emerged too, as elites, especially affluent professionals, expanded educational opportunities for their daughters. These institutions tended to be closer to home, especially the new primary and secondary schools like Dwight School (1880), Brearley (1884), and Miss Spence’s School for Girls (1892). When Columbia refused to admit females, Barnard College (1889) became the first secular institution in New York City to grant a BA to women.

Ecclesiastically speaking, Episcopalianism remained the favored denomination of both new and old Protestant elites. Henry Codman Potter, who became Episcopal bishop of New York in 1887, was pastor to the smart set and had several relatives on Ward McCallister’s Four Hundred list. He loved officiating at weddings between English aristocrats and the New York rich, and when he traveled to church conventions he rode in J. P. Morgan’s private railroad car. The General Theological Seminary expanded rapidly under Eugene Augustus Hoffman, its dean from 1879. Hoffman, descendent of an old Dutch family and owner of real estate worth millions, was said to be the richest clergyman in the world and was widely known as a sporting parson for his love of shooting and fishing and his active membership in the New York Riding Club.

Many believed that St. Thomas, on Fifth Avenue at 53rd Street, now surpassed Grace Church as the city’s most fashionable. It was certainly more sumptuous than ever after its reworking by Stanford White. (Other Episcopal Churches would strive for most sumptuous status, with the Church of the Ascension at Fifth Avenue and 10th Street employing the combined talents of Stanford White, La Farge, Louis Saint-Gaudens and D. Maitland Armstrong, and White designing an elaborate portal for St. Bartholomew’s at Madison and 44th.) Membership in St. Thomas was kept exclusive by charging pew rents of $500-700. On Easter Sunday, ladies of the church began parading up Fifth Avenue in all their finery, carrying the spectacular flower arrangements used for the service to patients at nearby St. Luke’s Hospital.

Way uptown, moreover, plans were under way for the erection of the biggest religious edifice in the city, indeed in the country—indeed in the western hemisphere. Bishop Potter took the first steps toward building the Cathedral of St. John the Divine at the end of the 1880s. The cathedral project gained important support from both prestigious Knickerbocker families and the more recently monied; the biggest contributors included John Jacob Astor, August Belmont, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the man described as “the financial and spiritual force behind the project,” J. P. Morgan.

The obverse of inclusion being exclusion, the upper class identified itself by the kinds of people to whom it denied access: Catholics and African Americans, of course, but increasingly, departing from prior patrician practice, Jewish New Yorkers as well. During the first postwar decades, most wealthy German Jews had lived amicably among their class counterparts in integrated neighborhoods. They sustained their own institutions, of course. They attended the Byzantine-towered Temple Emanu-El (1868) on Fifth Avenue and 43rd, sent their children to the Sachs Collegiate Institute (1871) on West 59th Street, and joined their own men’s club, the Harmonie Gesellschaft (1852). Many emphasized their Germanness: the Loebs and Lehmans spoke German at home, followed German affairs closely, vacationed at German spas, employed German governesses. But this cultural clustering was not the result of anti-Semitic rebuffs by their Fifth Avenue neighbors, as was evident from the ongoing memberships of assorted Seligmans, Hendrickses, Lazaruses, and Nathans in such exclusive precincts as the Union, the Union League, and the Knickerbocker clubs.

In 1877, moreover, when banker Joseph Seligman arrived at Saratoga Springs by private railroad car only to be turned away from the Grand Union Hotel by Judge Hilton, executor of A. T. Stewart’s estate (and soon-to-be hotel magnate), the incident produced widespread condemnation. Harper’s and the Tribune, Daily Graphic, Commercial Advertiser, Sun, and Herald all denounced anti-Jewish snobbery. When one hundred leading Jewish merchants successfully boycotted Stewart’s Department Store—also administered by Hilton—a Puck Christmas editorial offered “all honor to the Jews for their manly stand in this instance.”

The hotel did not, however, withdraw its exclusion policy, and indeed the practice spread. Starting in 1878 the Greek-letter societies at the City College of New York (as the old Free Academy had been renamed in 1866) barred Jewish members, something Bernard Baruch (class of ‘89) would long remember. And in 1879 Austin Corbin banned Jews from Manhattan Beach Hotel, explaining that such “detestable and vulgar people” were driving away respectable guests. Again, most New York papers denounced Corbin’s policy as mean-spirited, even shockingly un-American, and in 1881 the New York civil rights code that prohibited discrimination in public places for reasons of race was amended to include reasons of creed.

Nevertheless, anti-Semitic social ostracism grew steadily more acceptable during the 1880s, and by the early 1890s it had become a social given. In 1892 Theodore Seligman was blackballed when he sought to join the Union League Club—of which his father had been a founder—without eliciting a word of protest from members like Elihu Root and J. P. Morgan. This precipitated the resignation en bloc of all other Jewish members, many of long standing. Yet this time, while the Evening Post regretted Christians’ refusal to associate with even well-bred Jews, it also allowed as how people really shouldn’t try to push in where they weren’t wanted. Sephardic aristocrats and German financiers alike found doors around town slamming shut: Jews were excluded from the Social Register, banned from Four Hundred functions (not one was invited to the 1892 ball), and rejected from private schools. Some affluent Jews responded by assimilating all the more thoroughly; others circled their own wagons more tightly and established a “Hebrew Select” society.

Social exclusion fostered economic segregation. With prep schools explicitly geared to turning out Anglo-Saxon “Christian Gentlemen,” and colleges giving preference to sons of alumni, and few if any Jews (or Catholics, or African Americans) being accepted at top clubs, it became difficult, if not impossible, to accumulate the requisite old-boy connections, and banks, corporations, and law firms became Anglo-Saxon Protestant enclaves. Shoved to the side, Jews would advance only in industries they already controlled (merchandising and one wing of the investment banking community) or in fields still open to entrepreneurial innovation (entertainment and mass communications).

Yet the sequestration of elite Jewry would prove no more fatally corrosive of upperclass solidarity than the internecine combat between Astors and Vanderbilts or the acid rivalries of merchants and financiers. For all their internal conflicts, the issues uniting wealthy New Yorkers were far more compelling than those that divided them, and in the mid-1880s none was more urgent than the challenge issued to their political and economic authority from a very different part of town.