8. INDIGENOUS STYLES 1880–1930

The redundant must be pared down, the superfluous dropped, the necessary itself reduced to its simplest expression, and then we shall find, whatever the organization may be, that beauty was waiting for us.

—Horatio Greenough, Structure and Organization, 1852

The 1876 centennial exposition in Philadelphia triggered an interest in our nation’s history and a sense of self-confidence and chauvinistic pride. No less than half of the most significant national patriotic and genealogical organizations were founded in the years between 1876 and 1896. Historical societies were formed in every old town. An American way of life—more “informal,” “healthier,” and “wholesome”—was conducive to an architecture that was subordinate to and showed deference to our regional landscape and varied terrain.

We did not have to import standards of design; we had developed the clipper ship and the yacht America, the trotting wagon, the Astor House (New York’s first modern hotel), and the great Croton Reservoir. All were innovative and functional designs of exceptional utility and extraordinary beauty. Horatio Greenough (1805–1852) reminded us as early as 1843 that in art and aesthetics “the first downward step was the introduction of the first inorganic, nonfunctional element, whether of shape or color.”*

The Queen Anne and the Colonial Revival styles evolved in the 1880s and 1890s. They had derived from the more formal late Georgian and Federal styles but did not appeal to many Americans across the economic scale. Neither did the more pretentious European imports. Three distinct indigenous styles evolved, each in a different part of the country—one in the Northeast, one in the Midwest, and one in southern California—the Shingle style, the Prairie style, and the Craftsman style.

1) The Shingle style evolved in the Northeast as a cohesive, unified architectural mode inherently endowed with a sculpturally rich character that was distinctly American. While showing some influences from the English Queen Anne and the work of Norman Shaw (1831–1912) and his followers, Shingle houses demonstrated a mature style that drew from colonial precedent but with an entirely new sense of space, site, mass, and surface texture.

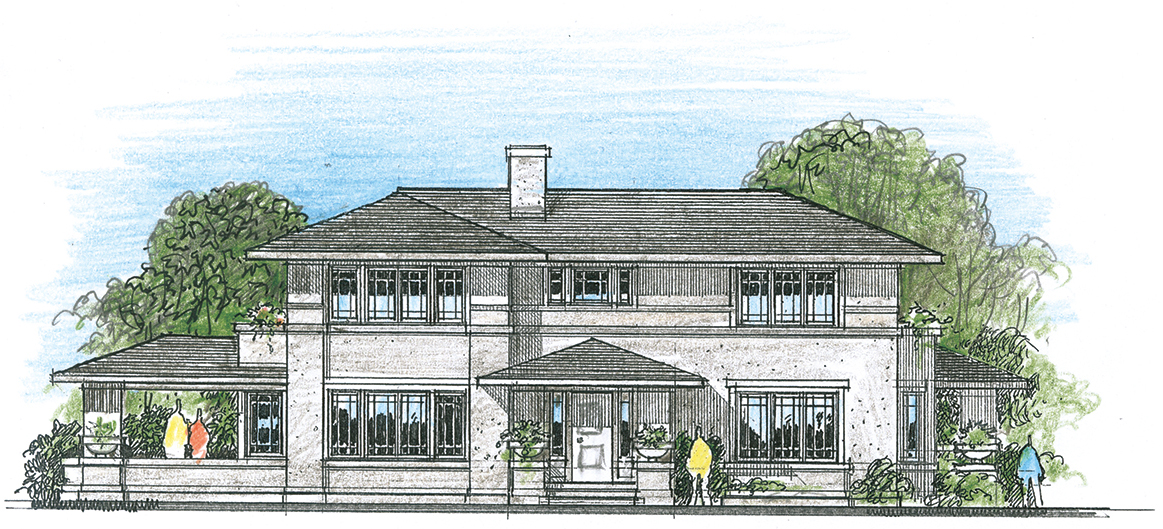

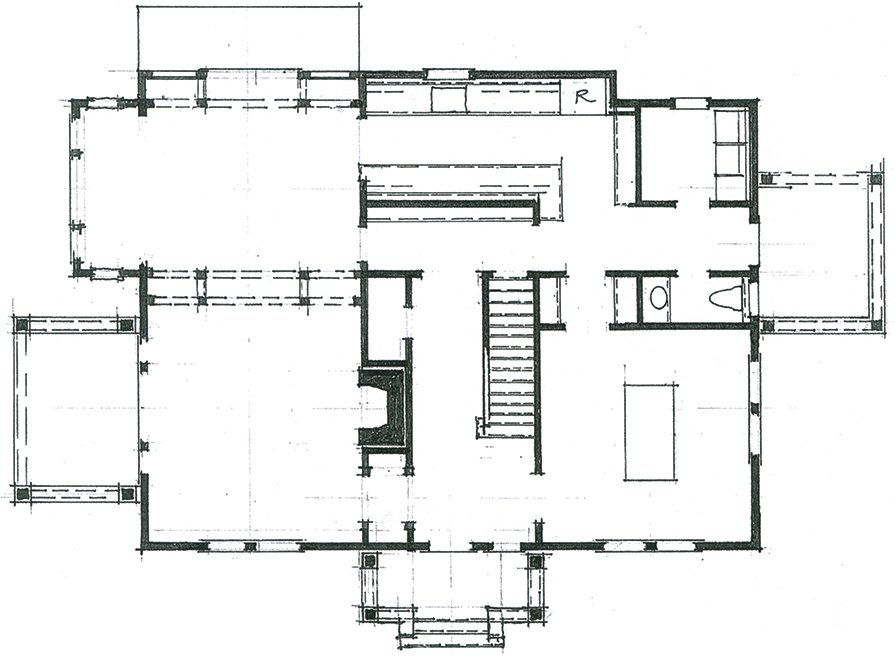

McKim, Mead & Bigelow designed a large house on Lloyd Neck on Long Island’s north shore for Mrs. A. C. Alden in 1879. It predated Richardson’s Stoughton house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, by three years and is the best candidate for the first landmark Shingle style house. Vincent Scully said in his book The Shingle Style that this house “is one of the simplest and most coherent of any of the country houses built in America in the period before 1880.”† Unfortunately the house was remodeled sometime in the early twentieth century and given a brick veneer. In popularity, the Shingle style was superseded by the revival styles around the turn of the century.

Fort Hill, Mrs. A. C. Alden House, Lloyd Neck, Long Island, New York, by McKim, Mead & Bigelow, 1879–1880

The same firm, but with Stanford White now a partner, produced the Bell and the Goelet houses in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1882 and the Low house in Bristol, Rhode Island, four years later. All were landmark Shingle style houses. In the mid-1880s they turned their efforts away from the Shingle style and launched the Colonial Revival with their Appleton house in Lennox, Massachusetts, and the Taylor house in Newport, Rhode Island.

2) The Prairie style was developed by Frank Lloyd Wright and his fellow architects in Chicago at the turn of the century and Wright was its most accomplished proponent. Considered “too outré” by eastern architects who favored the historical or traditional styles, the Prairie School flourished until the end of the First World War; it has come to be appreciated in recent years as a style very much our own.

3) The Craftsman style evolved with the bungalow craze which began in California in the late 1890s. The word “bungalow” apparently derives from the Hindi word bangala meaning “of Bengal.” The term was used to describe the one-story cottages with deep verandas used by the British officers in India during the days of the Raj.

Gustave Stickley published The Craftsman magazine from 1901 until 1916; it promoted houses that were “based upon the simplest and most direct principles of construction” and often featured the work of the Greene brothers. Charles S. and Henry M. Greene of Pasadena, California, were the first architects to echo the English Arts and Crafts movement in America and demonstrate the architectural potential of the Craftsman style. Some architectural writers call the Greene brothers’ houses “Western Stick” or the “California style,” but Craftsman seems a more appropriate term. Though lacking the sophistication of the Prairie style, the Craftsman interiors shared many characteristics—banks of windows, low profiles, open flowing floor plans, inglenooks, and the use of decorative banding with a predisposition for the horizontal.

Though they were submerged in the tide of reminiscent styles shortly before the First World War, all three of these styles, in their lack of borrowed or imported features, shone in their time as a beacon of rationality in a period of excess and disjointed eclecticism.

H. A. C. Taylor House, Newport, Rhode Island, by McKim, Mead & White, 1885–1886

Low House, Bristol, Rhode Island, by McKim, Mead & White, 1886

The term Shingle style (like “Stick style”) was coined by Yale professor Vincent J. Scully, Jr., and was the title of his excellent book, The Shingle Style, published in 1955. He traced the development of this style from its evolution in the years following our centennial celebration in 1876. Drawing from various genetic forebears—the Queen Anne, the vernacular colonial styles, and the contemporaneous Colonial Revival—the style blossomed as something new and fresh. The Shingle style was not just a new set of superficial stylistic elements, but an organic style with a character derived from an open, fluid plan. The sculptural expression of inner volumes was given a cohesive unity by the naturally weathered shingle siding.

Lower courses—not just the exposed portion of the foundations but sometimes the entire first story—were often made of masonry. Smooth bricks with ¼-inch mortar joints were commonly used in suburban settings, but often rustic stonework was employed in rural areas. Casement windows or double-hung sash windows were used and the sash was sometimes painted a cream color in contrast to a darker trim. Window trim was generally dark green or left natural. Unfortunately, many surviving shingle houses were highlighted with white in the Colonial Revival of the 1920s.

The architectural vocabulary used was vernacular but the actual compositions tended to be literate, articulate, and carefully edited. It is an architect’s style when fully realized-ordered, disciplined, and comfortable with a sense of casual dignity. Many Colonial Revival houses were sided with shingles—but usually with comer boards and four-square massing and so do not really qualify as Shingle style.

Incidentally, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park house that he built for himself in 1893 was Shingle style.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s own house, 1893

SHINGLE 1880–1905

Less than a decade after he built his own Shingle style house in Oak Park, Frank Lloyd Wright developed a new and distinct regional style: the Prairie style. It featured open planning; shallow-pitched roofs with broad, sheltering overhangs; bands of casement windows, often with abstract patterns of stained glass; and a strong horizontal emphasis. The siding was usually stucco, either off-white or an earthy tone, with decorative banding that echoed the low horizon of the midwestern prairie. Porte cocheres and raised porches extending out from the main core of the house were typical features of the style.

Prairie houses grew in popularity during the first decade of the twentieth century and had many promoters. By 1910 there existed a definite vocabulary that defined a natural house that was sympathetic to the regional landscape. The school invented new decorative motifs and rejected all details that derived from European precedent.

Though popular in the Midwest, the Prairie style offended eastern establishment architects who were promoting the reminiscent styles, particularly the Colonial Revival. The 1918 jury for “A House for the Vacation Season,” competition patronizingly awarded fourth prize for the single Prairie style submission with the comment that “it did not deserve all the cheap jokes passed upon it by its detractors.” The jury also compared Prairie houses to railroad sleeping cars and warned that the occupants would have “no more privacy than a goldfish.”

White Pine Series, 1918

PRAIRIE 1900–1920

The Craftsman style originated in California in the 1890s. Gustave Stickley promoted the style in his magazine The Craftsman which he started in 1901. It is occasionally referred to in a derisive manner as the “Bungaloid style.” Though the bungalow craze started in California as well, a bungalow is a building type and not a style.

The style is characterized by the rustic texture of the building materials, broad overhangs with exposed rafter tails at the eaves, and often extensive pergolas and trellises over the porches. Stone was never laid in a coursed ashlar pattern, but in a more random texture of rounded cobblestones. The lower portion of a wall was often battered or sloped near the ground. In the illustration, the porch columns are also tapered. The shingles on the second floor alternate with one course 2 inches “to the weather” and the next one 7½ inches exposed. Windows might be double-hung or casement, sometimes with different-sized window panes. The color and tone of the house derive from natural materials and an earth-toned stain applied to the wood. The Greene brothers’ houses in southern California are perhaps the most elaborate examples of the style; they were the ultimate in refined craftsmanship.

The Craftsman style persisted throughout the 1920s in summer camps and modest suburbs throughout the country. Sears, Roebuck, Aladdin Redi-Cut, and other manufacturers of precut houses shipped Craftsman style houses wherever there were train tracks to carry them. People could simply pick a house out of a catalog and send away for it. The house came complete with doors, trim, and even plumbing. Everything, in fact, but the foundation, the well, and the septic system!

Typical bungalow

CRAFTSMAN 1900–1930

* Greenough, Horatio, American Architecture, quoted in Hugh Morrison, Early American Architecture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1952; Dover, 1987).

† Scully, Vincent J., Jr., The Shingle Style (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1955).