ONE SUMMER MORNING, we walked out our dark thick door into the slanting sunlight. On our narrow street, along the base of the high white wall of our neighbor’s carmen, we found five soft pink mounds. It took us a moment to see that each one was composed entirely of rose petals.

All night, in the warm breeze, the rose hedges of our neighbor had showered the street with petals. And in the morning, the famously handsome street-sweeper, Salvador, had gathered and arrayed the petals with his nicety of judgment into symmetrical mounds. They glowed against the white walls of our street.

As we walked through the neighborhood, hardly a day would pass without some such event. Call them blooms of another sort—the flowers of idiosyncrasy.

GABRIELLA’S SCHOOL WAS at the top of the Albayzín, so we had the chance to amble together through the barrio, hand in hand, day after day. Come with us.

As Gabriella had her school, the joyful Arlequin, the barrio itself became our school. We, too, looked forward to leaving the house to explore the whole neighborhood, passing from sunlight to shadow and back again, as we walked along the narrow streets full of flowers.

Our carmen was not far from the Darro River, which runs along the southerly edge of the neighborhood. Walking north from the Darro, that is, going uphill through the Albayzín, if you would climb with us, you will rise about two hundred twenty feet and cover just over a half-mile to the top and northernmost point of the barrio, marked by the church of Saint Christopher. Going from west to east, that is, from Calle Elvira to the beginnings of the gypsy barrio, the Sacromonte, the distance is just three-quarters of a mile. In this small space, ten thousand people live.

As we go together through these streets, one thing is certain: we will get lost, and we will be glad.

The street pattern shows its medieval origin: narrow cobbled lanes, perfect for two people walking together. These pathways come together in whimsy, branching here into a stairway, swooping there round a corner, darting off sideways in shadow, only to open into a plaza with trees and fountains and benches. Walking around, at first you muse, then you are amused. To make sense of it, you must surrender wholly to the playful design. Rather than straight lines in a grid, we have here a puzzle, a subtlety, a crazy quilt and playground of streets, formed by a labor of centuries of the people of the Albayzín. Not only are the streets narrow and eccentric, but the walls reject the plumb line. It’s as if the whole barrio is on tilt—straight lines and right angles have been banished. Crookedness is the rule. Long garden walls lean into the streets or proceed in meandering waves along a lane. Inside the houses, everything is equally cattywampus. When we installed bookshelves in our house, the carpenter had to cut a subtle set of curves into the wood to fit the undulating plaster of the wall behind. Furniture we set down along a wall in a bedroom leaned comically forward, as though about to leap onto the mattress. And one of Gabriella’s soccer balls, placed anywhere on a floor, rolled off by itself, as though booted by a phantom.

We came to love this swerve and tilt of things. Rather than clear lines of conceptual order, this was a neighborhood full of buildings that showed by their worn and worked surfaces their centuries of usefulness to life.

Most of the houses are white, often two stories with an occasional tower rising to a third story, for a lookout, a workroom, a trysting place. In some houses, windows open onto the street, and on the second story the house walls are studded with black iron balconies whose high doors can be thrown open to the sun and air. If the house is a carmen, then walls without windows enclose a secret garden, which shows above the wall some of the thriving within: palm trees, junipers, persimmon trees, a grape arbor, sunflowers, orange and lemon trees. From these gardens, vines and flowers clamber over the walls and arc down toward the street: roses, pink trumpet flowers, ivy, plumbago, white and gold-leaved jasmine, bougainvillea. At any time walking in the Albayzín, you may turn a corner and find a full current of flowers spilling toward you. Sometimes, with the bougainvillea, more than a current—an avalanche of flowers.

Our street, at its widest point, is about seven feet—just wide enough for Lucy and me to walk with our little daughter toddling between us. Many streets are more narrow, with bizarre angles, zigzags, and high, haggard walls that shadow the street even in midsummer. And some streets, known by a Spanish word—adarve—lead nowhere. You walk down one such lane, and it may end abruptly in a wooden door so worn you begin to think in geological time. The neighbors will say they believe it is used, but no one has ever been seen going in or out. My theory is that the doors at the end of adarves open into the tunnels in space and time that physicists tell us about, and so lead us to the past or future, or even to other interesting and habitable planets. Advancing this theory over brandy in nearby cafés, I received knowing looks.

Be that as it may, on the streets of the Albayzín, we have been lost, and early in our wanderings we noted the key principle: the barrio was not made for automobiles to live well. It was made for people to live well. There are only two roads that pass east to west through the Albayzín; they are used principally for public transport, and on one of them is located the single large garage for private cars. Going north to south, the only roads run at the far edges of the barrio. What difference does all this make in life?

It’s a godsend. Gabriella and her legion of friends (and their parents with them) could rumpus in the little streets, invent stories, play soccer, sing to the trees, and in general dash around unforgettably, yet every parent is easy in the flesh. No truck is going to crush the children. Not only are kids safe, but the neighborhood is quiet, with no spewing and hacking of internal combustion engines. But even more than all that, something obvious and splendid: none of your neighbors are walking out to find their cars and go off to their lives. They are all walking out, straight into their lives. So all of us who live here run into one another, often. What begins with salutations turns easily to stories, to curiosities and exclamations, all of it leading to a friendship that has our children playing at each other’s houses. This happened again and again in the Albayzín. It happens because our neighbors have sweet natures, and it happens because the barrio itself, the very design of it, has a genius, an irrepressible, gift-giving life.

Take, for example, Plaza Larga, in the upper Albayzín. We passed through it on the way to school and always paused to take in the spirits of the place. You walk into the plaza through an arched gate in a fortress wall at least a thousand years old, built on the foundations of another wall made a thousand years earlier. It is where Lucy and Gabriella and I dined our first night in the Albayzín. On weekdays, the plaza is filled with fruit and vegetable stands on one side, and at the other, a rack and tables of clothes for sale. Nearby is a legendary café, Bar Aixa, with coffee so intoxicating it should qualify as international contraband. Along the two mains streets that lead from the plaza—Calle Panaderos and Calle Agua (the street of the bakers and the street of water)—you’ll find a hardware store, a ceramics store, fish markets, restaurants, a pharmacy, remnants of Arab baths, a big church that preserves the courtyard of a medieval mosque, small grocery stores, a newsstand, a flower shop, the butcher, the baker, and, I am sure, the candlestick maker. It’s roistering and buoyant, with babies in strollers, kids hiding behind piles of artichokes, nuns gliding to and fro like swans, shouts of recognition or outrage, a garrulous humming of conversation, a blind gypsy selling raffle tickets, and black-garbed old women sitting on benches and talking, no doubt, about Aquinas. And of the side streets, you’ll find work that asks more solitude and intensity—the guitar maker, and a world-class blacksmith.

Action and repose, idiosyncrasy and purity, flowers and surprises: the Albayzín offers daily some strange art of cumulative beauty. As the days and months pass, wherever you go, a host of details quicken the senses. Because everyone is living so close to one another, yet privately, life is in your face with rough edges, past tragedies, and a daily sense of promise. What came round to us, as we walked here, is a certainty that each day, we have our chance.

One might think that a neighborhood composed of small buildings, close together, and using so few elements—gardens, stone, brick, wood, plaster—would be monotonous. All the more so since, constrained by the rules that govern historic neighborhoods, no one may construct, say, a three-story aluminum house with a front lawn and a big garage. But the severity of the constraints invites beauty to move in and stay awhile. An analogy is the sonnet: with its strict fourteen lines, rhyme, and metrics, the form does not limit our labors, but offers a place where meaning may flourish.

So in the Albayzín, the restricted space, history, simple building materials, and municipal regulation have created a place where daily life may flourish. In fact, all the rules have ignited the most promiscuous variety of ideas for making a space to live. One day, walking around, we chose one element in the barrio, the terrace, and we made it our study. The first terraces we see are tiny balconies, looking like aeries, which can be reached only by spiral staircase. Others have cane roofs and resplendent tiles; they are outfitted with chairs and a table for sherry and open toward the Darro and the Alhambra. Larger terraces have canvas awnings and iron railings woven with honeysuckle, within which a bed may be hidden, for an outdoor tryst. Some terraces at the top of a house have four-sided tile roofs of shallow pitch, open to the air on all sides and holding a white hammock strung between posts; others are without any roof and open to the stars and to the mystery of the city. The largest terraces you enter through arches of plaster carved in arabesques and painted in soft azure, and walk onto an esplanade whose swirling pebblework floors hold pools of cool water for blessed relief from the summer heat. One could take a summer, walk around, go to the heights of the Alhambra, look over the whole of the Albayzín, and write the definitive treatise on terraces. Or chimneys. Or garden pathways, rooflines, the shapely columns that support balconies around a courtyard full of flowers—for in the Albayzin, these common elements come into the most bemused variety. With a few rules and a handful of elements, we have a feast of forms. And all of them within one small barrio, fifteen minutes to walk, from the river to the church at the top of the hill.

If you and I walked through the Albayzín, to school or to market, to see friends or just to have a ramble; if we took a whole day, what would we find? Among white walls, flamenco guitarists practice. And flamenco singing—at once fierce and melodious—comes from doorways and terraces. Wafting from windows is the sound and smell of the simmering in olive oil of lamb or onions and tomato. We hear jokes being made, the susurrus of conversation, rambunctious toasts, a clink of dishes being washed. Around the next corner, a dozen orange trees in full blossom in a big carmen. Around the next, a little plaza with a bench, and a brouhaha of bird songs—because of all the gardens and plazas, the barrio is full of swifts and magpies. Sitting in a plaza, you may see through a gate to a wall of tiles that makes up a fountain—white stars set in large squares of baked clay. By your side, through another gate, another fountain, this one faced with blue and green Moorish tiles, and beyond it a kitchen garden in a surround of fruit trees, all meticulously kept. Moving on, we watch the light of the afternoon slant across one lane, fill another to the brim with soft heat, and fill the next with a filigree of shadow as light passes through the leaves of a grape arbor. As the afternoon carries on, we rise though the lanes of the barrio to see junipers straight as geysers and windows covered and adorned by wood jalousies, whose openings are six-pointed stars, so that when the sun flows through, the walls within are bright with their own constellations. Some houses have a torreón, a high, open room whose ceiling has fine wood carvings called alfarjes, with their own mystical geometry. Walking higher up the narrow streets of the barrio, we come to a door set in a horseshoe arch, that arch itself set into a classic pattern of tiles, this time of ten-pointed stars that move, grow, and unfold before you. If we carry on until the sky darkens around, the lights of the Alhambra come on, and we turn around to sudden views of a pale stone tower rising out of a dark green hillside. Another few minutes, rising higher on the hill, we see the whole palace, curiously graceful—as though stone could float.

At night, iron and glass streetlights come on throughout the Albayzín, amber lights glow in the bell towers of the churches, white lights stream from the doors of little bars whose hubbub falls on the street like bright paint. In quiet stretches of meandering streets, and in tiny, isolated plazas called placetas, there is peace, and occasionally, thieves. Shadows patch the white walls, so they look like the robe of harlequin. Young people gather in plazas to drum and kiss and swig hard liquor.

How does any place become so eccentric, exultant, and hard-scrabble, all at once? By sheer unlikelihood, and as a result of twenty-seven hundred years of luck and work and anguish. It’s a story that begins early, in the seventh century BC, so long ago it’s the century of the Old Testament Jeremiah.

The Albayzín holds a history of pagans, wacky church councils, classical civilization, genocidal outbursts, amorous shenanigans, incomparable works of genius, terrible religious fevers, and ethnic cleansing—all these, set into a story of Visigothic, Roman, Islamic, and Christian conquests. It’s as if the great currents of Mediterranean history all coursed through this one neighborhood. If this were not enough, it’s a history that holds as well the discovery of Holy Scripture from the first century bearing the magical Seal of Solomon. It was a find that rocked the Christian world.

Into that history we now gave ourselves, in hopes of understanding where we now lived. The story of the Albayzín led us into so zigzag and labyrinthine a maze, it was as if, in our reading, we walked in the barrio itself.

THE LAND, IBERIAN MYSTERIES, PLEASURES OF THE ROMANS

Let’s start with the geography, which could hardly have conferred more blessings upon a townsite. To the southeast, the Sierra Nevada arcs into view, the highest range on the Iberian peninsula, with peaks rising beyond eleven thousand feet. To the east, another range, the Sierra de Huetor, full of springs, forming the headwaters of the Darro River running at the base of the Albayzín. South, just across the Darro canyon, is the Sabika hill where the Alhambra was built. On the far side of the Sabika runs the boisterous Genil, coursing with snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada.

It has extraordinary sweetness: big mountains, broad foothills, a promontory aloft between two rivers, the warm high hill of the Albayzín looking toward that promontory, all complemented by a plain—the vega—of rich soil, superbly watered with torrents of fresh snowmelt, and stretching out under hot summer days. Circling the vega, more mountain ranges, leaving only narrow passes for entry. Formidable security, then, for the city, and for its agricultural lands. Early communities on the lookout for a place to settle must have counted the advantages and gone off straightaway to thank their gods.

It is the seventh century BC. In the eastern Mediterranean, the Assyrian empire shoulders its way into Egypt. In Greece, Athens is already a politically complex city governing most of Attica. In the west, Etruscan civilization is flourishing on the Italian peninsula. Celtic tribes, with their iron weapons, settle in Gaul. And right here on the hill of our Albayzín, the early peoples of Spain built a compact, fortified city. They are called los Iberos—the Iberians—and they still fascinate Spain, since they have whimsically withheld so many of their secrets. But they chose the site so intelligently that future settlers—Roman, Visigoth, and Arab—would build their walls on the foundations of Iberic walls.

They constructed their city at the high point of the hill, with good vantage up the Darro canyon and out toward the vega. Every day, on the way home from Gabriella’s school, we walked by an excavation that seemed to go on endlessly. Finally, we stopped and talked to the workers, who of course threw down their tools, lit cigarettes, and explained everything to us as Gabriella ate her ice cream.

It turned out that in the area near the site, closer to the stone gate that gives entry to Plaza Larga, near the bars and schools and bakeries, archaeologists have dug up the foundations of houses and sanctuaries twenty-seven hundred years old. They’ve found ceramics, money, inscriptions, and urns; even a whole necropolis. And slowly, in combination with other finds throughout Spain, the culture of los Iberos has come into view. They left us lovely small bronze horses and little soldiers with tiny shields and swords, who go into battle very warily indeed, since both sword and phallus are erect. They left famous sacred statuary of women in elaborate robes, tightly wound hairdos, and clunky necklaces; their female gaze is fixed so intently on some faraway world that we want to turn our heads and look carefully, just in case it swims into view.

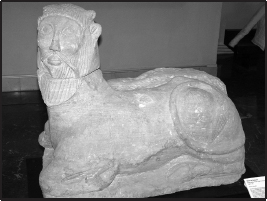

They left us coins and tablets with their written notes and declarations in a language that has stumped the scholars who have studied it. So we await their poetry and their praises of the strange goddess. Best of all, they gave us what has to be my favorite sphinx, a muscular bull with the head of a man, mustachioed and irresistibly jolly. Even to look at the thing makes you laugh.

In their redoubt at the top of the hill, the Iberians lived for five centuries, until Rome began to march its legionnaires all over Europe. The date given for the beginning of decisive Roman influence on our hillside is 193 BC. Iberian culture makes a slow marriage with Roman law and custom. By 1 BC, Latin, which at least we can read, was the language stamped on money. Being no fools, the Romans took one look at the Iberian fortified city on the hill overlooking a river and a fertile vega and moved right in. They built stronger and higher walls, extending the footprint of the settlement to the west and south, that is, toward the vega and down the hill toward the river. We could walk with you from our carmen, going north up the gentle hill, and in two minutes arrive just where the Roman wall ran east to west along the present street of Aljibe de Trillo. From their freshly fortified vantage point, the Romans set to work, bringing to the art of ceramics what have to be the dullest pots in the history of the region—the pieces are covered with red varnish, making them look even more like mud than they would otherwise. But at least they had dishes.

Farther afield, the Romans did their Roman things: found gold in the Darro and Genil and created quarries in the foothills so they could carry on building. Above all, they grew satisfied and prosperous from that root and font of wealth, agriculture. With the vega under their military vigilance and production organized into large estates, their tables were laden with grapes and cereals and olives. With the heat of the summer, the swollen and luscious grapes of the region made their way, suitably stored and aged, to wine-bibbing citizens who partied in seigniorial mansions whose foundations have been excavated in the Albayzín. Those mansions, of worked stone, sometimes built up ingeniously without mortar—called in Spanish mampostería—were so well put together that their walls, in the open air after twenty centuries, stand intact and strong. In our wanderings around the barrio, we have seen them; they look as if they were held together by some undiscovered cosmic force. Some houses even had the mosaic floor found elsewhere in the empire—an oddly direct precursor of some of the streets in the present-day Albayzín, which have pebbles inlaid laboriously in the form of flowers, or pomegranates, or arabesques sinuous as wind.

The Ibero-Roman city held the usual Roman accoutrement—a forum, basilica, courtyards with columns, marble statues, and the lot—so that the soil of the Albayzín has proved to be a lumpy staging ground for the discovery of cornices, fountains, republican and imperial coins, fluted columns, and affectionate inscriptions in praise of slave boys. And we find also one detail that was to mark the Albayzín forever: reading of it now, we have the sense of something coming to be born. In the upper reaches of the Albayzín hill, a Roman house was excavated with a fine small pool, lined with bricks, which must have looked out over the countryside. And why not, since the ingenious use of water would transform the Albayzín—the clear, fresh water from the mountains, in its full sensuality, that has flowed into the neighborhood over centuries like some benediction of history.

When on a mercilessly hot day in the summer we throw ourselves into the cool water of the alberca in our garden, I think of our Roman antecedents, who doubtless did the same, with the same joy and relief. There were springs on the hill of the Albayzín, and on the hill above, and Roman roofs were designed to drain water into underground cisterns, just as hundreds of years later, cisterns would be built throughout the neighborhood, even within houses. We have an ancient one in our own carmen. We have thought to make a cellar, or fill it with garden vegetables on shelves, or set down racks for wine. But it seems somehow to want to persist in its historic form.

In this Roman period of the Albayzín, the region steps out onto the stage of the world. In the first century of the Christian era, Pliny the Elder wrote his Natural History, wildly subtitled “An Account of Countries, Nations, Seas, Towns, Havens, Mountains, Rivers, Distances, and Peoples Who Exist Now or Who Formerly Existed.” He tells us, wonderfully, that the region “excels all the other provinces in the richness of its cultivation and the peculiar fertility and beauty of its vegetation.” Two Roman emperors—Trajan, who broke the monopoly of Italians in that august position, and Hadrian, the orphan turned lover and warrior—were born in Andalusia. And the future Albayzín turns up in Pliny’s summary of the towns in the region, under the name of Iliberri or Ilupula. My guess is that these names were chosen because they feel ripe in the mouth.

And we begin to see others come forth from the hillside of the future Albayzín to historical notice. Let us name one of them: Publio Cornelio Anulino, who was, if we may be permitted a deep breath, quaestor, tribune, legate, commander of the Seventh Legion, sometime governor of the Roman provinces of his home territory Baetica, as well as Africa, and Germania Superior (which is present-day eastern France), and eventually a prefect in Rome—that is, a key player in the administration of the empire. The compatriots of this gentleman, over the centuries, were variously soldiers and consuls and priestesses, giving us a sense of the high energy of the locals. Perhaps it was the trustworthy sunlight and delicious red wine of their hillside neighborhood.

It is at the close of Roman domination that we witness the Albayzín begin to consider how to mix pagan devotion with Christian and Jewish practice, since all three ways of worship existed here. With foreboding and fascination, we may watch how, very early on, men of faith in the Albayzín tried to turn the centuries in their direction.

THE CLERGY GATHER IN THE ALBAYZÍN TO TAKE A CRACK AT HISTORY

In the first centuries of our era, Christian communities, fledgling and persecuted, spread though the Mediterranean and had a beachhead, literally and figuratively, on the Iberian peninsula. Official tolerance throughout the empire was not, of course, granted until February of 313, with the Edict of Milan, which gave Christians legal rights, restored their confiscated property, and permitted the founding of churches. So it is with astonishment that we read of a council of the church held in southern Spain that predates the Edict of Milan. Called the Council of Elvira, it took place around 306 AD. A mighty weight of church officials—nineteen bishops with assorted presbyters, deacons, and legates—gathered on this hillside overlooking the Darro and the vega and cogitated piously about orthodoxy, sin, punishment, women, pagans, and Jews. We wonder if they knew what they were doing, especially how their musings would reverberate down the centuries. For the Council of Elvira was not just the first church council in Spain. It was the first council anywhere from which written canons survived. It is a fascinating episode, for we see in its daft propositions a young church besieged with events and confusions, and trying to figure out what on earth to do. Some of these early canons have the feel of grumpy social judgments, such as:

62. Chariot racers and pantomimes must first renounce their profession and promise not to resume it before they may become Christians.

So were those rakish charioteers and suspicious entertainers cast off by this stern group. And the church wanted to tidy up the churches, even venturing this bold proclamation:

36. Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not become objects of worship and adoration.

Iconoclasts before their time, this attitude would destroy, in the centuries to come, uncounted mosaics and paintings. For the sake of Fra Angelico, Raphael, Bellini, and the countless other luminaries of Christian art of the ensuing centuries, we may be permitted a prayer of thanksgiving that this canon did not prevail.

But beyond the housekeeping, the reach of the canons is extraordinary. They are seeds, set down in the Albayzín, that grew into history. An extraordinary number of them—a full quarter of the total—assert control over women’s conduct, especially of woman’s sexuality. As to conduct, some canons are so persnickety that we want to know the story behind them. There is, for example,

67. A woman who is baptized or is a catechumen must not associate with hairdressers or men with long hair. If she does this, she is to be denied communion.

This particular canon has the smell of a grudge: a hopeful deacon, say, mad at a lovely Christian girl cavorting near the Darro, her hands in the long hair of her suitor. A long-haired charioteer, perhaps? There is another of this same stamp:

81. A woman may not write to other lay Christians without her husband’s consent. A woman may not receive letters of friendship addressed to her only and not to her husband as well.

No doubt such letters had been discovered, who knows with what promising innuendos.

But beyond such curiosities, the struggling church exerted itself to name and regulate the sexual antics of Christians. To judge from the canons, the council must have spent long days on the subject. Perhaps the sensual climate of Andalusia had heated the theological reasoning of our clerics. Witness the following canons. Some are crisp and forgiving. Such as:

44. A former prostitute who has married and who seeks admission to the Christian faith shall be received without delay.

A host of canons then go on to study adultery with what we might call algebraic exactitude, and try to cook up different punishments, depending on gender, faith, and the sexual facts at hand. The permutations are endless, as though the august assembly of clerics felt compelled to list all the couplings ever confessed. Some of these are wonderfully phrased, with a lot of ferocious prohibitions which give way to a wonder of hedging, backtracking, and exception-making. The results are bizarre, even for a church:

9. A baptized woman who leaves an adulterous husband who has been baptized, for another man, may not marry him. If she does, she may not receive communion until her former husband dies, unless she is seriously ill.

Then, of course, what about sexual variety? And certainly they had to consider the case of a cleric who adores his adulterous wife—

72. If a widow has intercourse and then marries the man, she may only commune after five year’s penance. If she marries another man instead, she is excluded from communion even at time of death . . .

65. If a cleric knows of his wife’s adultery and continues to live with her, he shall not receive communion even before death in order not to let it appear that one who is to exemplify the good life has condoned sin.

We note that it seems to have been common for a priest to have a wife.

Having begun to tidy up the lascivious behavior of the married clergy and laypeople, they forged bravely ahead in the hopes of assuring that virgins remained virgins; unless, of course, they didn’t, in which case the ex-virgin could make amends. This was tougher for so-called consecrated virgins, the forerunners of nuns. For a lay-woman, all depended on the number of her lovers. The more sexually active the woman, the more amends would be required. What’s interesting is that even though such amorous conduct got a big frown in the canons, such women still had a way to enter the community of Christians.

13. Virgins who have been consecrated to God shall not commune even as death approaches, if they have broken the vow of virginity and do not repent. If, however, they repent and do not engage in intercourse again, they may commune when death approaches.

14. If a virgin does not preserve her virginity, but then marries the man, she may commune after one year, without doing penance, for she only broke the laws of marriage. If she has been sexually active with other men, she must complete a penance of five years before being readmitted to communion.

Having reviewed in such detail the sexual frolics of the community, it probably was inevitable that the clergy address their own conduct. And so fate had its way when the council, having cast so critical an eye on the embraces of laypeople, now turned with severity on each other.

27. A bishop or other cleric may have only a sister or daughter who is a virgin consecrated to God living with him. No other women who is unrelated to him may remain.

Note the daughter! And the sizable begged question, crying out to be answered: What about a woman who is related to him, who does remain? And the council dropped its bombshell:

33. Bishops, presbyters, deacons, and others with a position in the ministry are to abstain completely from sexual intercourse with their wives and from the procreation of children. If anyone disobeys, he shall be removed from clerical office.

It is a calm, stunning, momentous prohibition, the first such canon of the Catholic church. It does not forbid the marriage of clerics; rather, it reaches into the heart of such marriages, to forbid the physical celebration of a man and woman promised to one another. To cherish the pleasures of a wife is to abandon the work of the church. And implicit in this reasoning is the idea that such cherishing cannot lead a couple in love close to life, or closer to the divine.

It is the declaration of one small church council, in a small settlement on a hillside in southern Spain, far from Rome and Constantinople, early in the history of Christianity. Yet we should not discount its power and influence. Later canon law tended to build upon the cracked foundation of Elvira. Not only that, but of the nineteen bishops in attendance, some of them would go on to play crucial roles in later councils. To mention only one: Hosius of Córdoba, a key player in the Council of Elvira, went on to participate in the authoritative Council of Nicaea in 325, perhaps in the name of the pope himself. Hosius even managed to totter, at age 99, all the way to the Council of Milan in 355. Such councils, with the promulgation of the Nicene Creed and its confirmation thereafter, set down a fierce and final theology that has remained in place to our day. If the Council of Elvira had understood the world differently, today our world would be different. And whatever one thinks of the blizzard of prohibitions of the Council of Elvira, some of their canons we must read today as a planting of evil seeds:

49. Landlords are not to allow Jews to bless the crops they have received from God . . . Such an action would make our blessing invalid and meaningless. Anyone who continues this practice is to be expelled completely from the church.

78. If a Christian confesses adultery with a Jewish or Pagan woman, he is denied communion for some time. If his sin is exposed by someone else, he must complete five year’s penance before receiving the Sunday communion.

So Jewish blessing is condemned, and as to sex, a Jew is no better than a pagan. But the council was not done.

50. If any cleric or layperson eats with Jews, he or she shall be kept from communion as a way of correction.

A mere three centuries after the death of Jesus, a Jewish teacher in Palestine, it is an early, clear expression of contempt.

The Christian community in the Albayzín, entrenched and literate, continued to be influential. In the fourth century, a bellicose and orthodox bishop, Gregory, lived in the Albayzín. In addition to penning five volumes on the Song of Songs, he took the time in another book on the Old Testament to detest Jewish religious observance. And we must not forget the hysterically ambitious Juvencus, also of the early fourth century, born into the neighborhood, a presbyter and budding epic poet. Juvencus wanted to get rid of those ancient pesky storytellers, Homer and Virgil. To replace their unholy paganism and messy digressions, he left us a tidy Latin commentary on the New Testament—no fewer than 3,211 verses in dactylic hexameter. No old-fashioned muses are to be found; he happily substitutes, in their stead, the freshly minted Holy Spirit.

THE VISIGOTHS LOSE THE NEIGHBORHOOD TO AL-ANDALUS

In the fifth century, into the Iberian peninsula and eventually to the Albayzín, came the Germanic invasion that extinguished the Roman Empire. The skirmishing tribes that ransacked the Iberian peninsula have names that stick in the mouth like clay—the Siling Vandals, the Alans, the Suevi, the Asdings, the Visigoths. Our neighborhood saw these newcomers hacking away at Romans and one another, as it was dominated first by Visigoths, then by Suevi, then again by Visigoths, until by the sixth century the Visigothic aristocracy supplanted the dominant Roman families, and Roman villas sported Visigothic decoration. Even Granadan bishops took on Visigothic names, which is fascinating, because the Visigoths were not what we have come to call Orthodox Catholics. This being early in the struggles of the young, sprawling church, fundamental ideas were still in play. The Visigoths were Arian Christians. Now, library shelves have been broken by weighty books written about Arianism, and rightfully so. Let us boldly summarize: the Arians believed that Jesus, though a divinely inspired prophet, was not himself divine; and so Jesus is the “Son of God” not in a literal sense, but in an emblematic sense. Think of him as being adopted by God, because of his loving, his goodness, and his understanding. The Christianity of the Arians, then, stood in contradiction to the orthodoxy of the Council of Nicaea, which held Jesus to be divine, literally the Son of God.

The Albayzín, then, was full of Arians, which goes to show some things never change. The neighborhood is freewheeling and rebellious now, and so it was then. It’s something about all the sunlight and music, we think. In any case, throughout the Mediterranean, Christians of the early Middle Ages fought about the nature of Jesus. They battled it out in Iberia, as well, and the story is full of rousing political intrigues, conspiracies, exiles, excommunications, and miraculous reversals of fortune. In Iberia, in 580, Leovigild, the Visigothic king, gathered the Arian bishops of Spain in a synod to set forth a new Arian Christian orthodoxy. Unfortunately for his initiative, Leovigild’s son converted to the Nicene Creed, which held Jesus to be divine. He went to war against his father, only to be captured, imprisoned, and, then, rather conveniently, murdered by his jailer. After all that, Leovigild’s other son, Reccared, assumed the kingship—and then himself converted to the Nicene Creed. Arian bishops revolted. The monarchy threw itself into the arms of Orthodox Catholic Christianity, and the hubbub continued. Reccared’s son was assassinated, and his murderer, Witeric, tried to bring back Arianism; but alas, Witeric was decapitated at a banquet. So went the pacific exchange of ideas that formed Christian theology in Spain.

So our Albayzín, after centuries with the Iberians, Romans, pagans, Jews, early Christians, then pagan Germanic invaders turned Arians, finally cruised into the seventh century full of Catholics who kneeled down and swore to the Nicene Creed in their churches. Their Visigothic rulers went on to distinguish themselves by a habit of internecine slaughter and, just to round things out, a doctrinal hatred of the peninsula’s substantial Jewish population.

When, in 711, Tariq Ibn Ziyad turned up with his seven thousand soldiers, everything changed for the Albayzín, for most of the Iberian peninsula, and for Europe. It was the beginning of Al-Andalus, and we still live with the forms and in the light of those eight hundred years. The Albayzín, in particular, takes from that period the layout of its streets, its architecture, its monuments, its gardens, and myriad elements of its way to life.

The Arabs and Berbers, both bearing Islam to the peninsula, came first as soldiers. But the swift collapse of the Visigoths delivered the entirety of Iberia into their hands, and they stayed on as settlers. Our hillside, with its customs and churches and history of agreeable habitation, yielded itself easily to the newcomers, not least because of the help of the Jewish population of the city. In the years following, we hear of the future Albayzín now and then in the historical record. In 743, a group of Syrians received permission to set up house in the neighborhood. We have excavations of some of their houses from the period, with cannily constructed walls of stone, private baths, and interior patios. In 755, the first emir of Spain, the gardening Abd al-Rahman I we have met, gave his permission to fortify the building on the Sabika hill, on the site that would one day hold the Alcazaba, fortress of the Alhambra. We have a picture, then, of a small community now spread over the hillside of the Albayzín and the Sabika hill, with a small, politically dominant Muslim cohort, a vigorous Christian presence, and a well-established Jewish quarter.

For the first three centuries of Al-Andalus, much of the action moved to another hillside to the west, farther from the Sierra Nevada, but still with good access to rich agricultural lands. The settlement there, called Medina Elvira, flourished until the beginning of the eleventh century, when the momentous decision was made to move everyone to the better-fortified and tantalizing hill of the future Albayzín. So began the reign of the Zirids, a Berber tribe whose kings, in seventy years, made the fine judgments that formed the neighborhood where we live. They brought power and big plans, but most of all a thoroughgoing practicality. They built the walls we see today, and some of their gates we still have, like the Arco de las Pesas, that gives access to Plaza Larga. They built a mosque, the Almorabitin, whose minaret (now a belltower) still stands, with rough, admirable beauty. Most of all, and best of all, they brought water. It came from a miraculous spring called Aynadamar, across the foothills to the top of the Albayzín, and flowed through the neighborhood, to be collected in twenty-eight cisterns called aljibes. You can still see them in the Albayzín, like stone keys to the heritage of life here. It is worth quoting a description of the water:

The water is most healthful, and a natural medicine against fevers and so helpful to the digestion, that no matter how abundant the food, it passes easily through the stomach; its temperature is that of natural springs, warm in winter and cool in summer, and so clear and delightful to see, for its bounteous quantity and its effervescence, that for it alone Granada would be superb, even if the city did not have so many other excellent qualities.

Even to read about it makes one thirsty. The engineering was so sound, it lasted a thousand years. There are still residents in the Albayzín who remember drinking this water. Such are the virtues of thoughtful engineering—a millennium of daily benefits.

In that same eleventh century, a king by the name of Badis built his palace somewhere around San Miguel Bajo, a plaza today full of restaurants and rollicking children. The settlement expanded, and the walls with it, and neighborhoods radiated out from the central, fortified zone, which remained where it had been for the previous seventeen hundred years. The new barrios took on their wonderful names: there was a Barrio of the Caves, of the Cliffs, of the Potters. There was a Barrio of Delights, of the Solitary Worshippers, and finally, just on the other side of the Arco de las Pesas, the Barrio of the Falconers. It is this last barrio—ar-rabad al-bayyzin—whose name gives us Albayzín. Though men with falcons on their wrists are rarely sighted, at least for now.

Throughout the Iberian peninsula, political power knotted and unknotted whole regions, as armies led by Christian sovereigns advanced from the north, won and lost battles, and the leaders of Al-Andalus, whether Christian or Muslim, made and remade alliances with one other. But Al-Andalus, whatever the governance of its cities and regions, continued to be the same fecund mix of language, faith, and art, with strong Christian, Jewish, and Muslim communities. And the Albayzín—the core and origin of Granada, was to be for two and a half centuries a place for kings.

After the arrival of the community of Elvira, the Albayzín remade itself into an energetic, well-fortified city. To the provision of sparkling water, successive kings and their talented subjects added a large hospital, new mosques for the increased population, and a bridge across the Darro to permit easy access to the Jewish quarter of the city and to the fortress atop the Sabika hill. Today, one may walk in a matter of minutes from our house to all these sites. The twenty-eight aljibes have been recovered. The footings of the bridge across the Darro still stand; in the nineteenth century, they were to give a Romantic frisson to visitors from France and England.

The population grew and changed and strengthened as new skills were demanded, and new prosperity incited a new way of life. The number of people in the Albayzín began a steady climb that would culminate, after four centuries, in a population of around forty thousand people, a nice medieval contrast to the ten thousand who live here today.

During this time, the neighborhood took on the quality that, as we read about it today, impresses us: rambunctious diversity. Already diverse in religious faith, with the agricultural bounty to support them, the community came into its own. Who were these people, what did they know, how did they live?

There were farmers, laborers, muleteers; millers, bakers, basket-makers. There were tile-makers who were to carry further the rich traditions of arabesque and ingenious geometry; there were potters who adorned vases and plates with lovely blue and green designs. So lovely that when we bought a set of plates for daily use in our new kitchen, the paintings upon them turned out to be copied from a fourteenth-century original. There were wood-carvers who translated the octagons and whirling dodecagons of the tile-makers into ceiling panels of wonderful, sidereal variety. There were the famous orchardkeepers, who produced for the city a promiscuous variety of fruit—peaches, grapes, pomegranates, figs, apples, oranges, dates, lemons, along with pistachios and cashews. Through the Albayzín, and down in the marketplace that developed in the level area just west of the neighborhood, there thrived the specialists—blacksmiths, rope-makers, shoemakers, book-binders, stonecutters, pharmacists, midwives. In the Albayzín itself, the spinners of silk made the silk merchants and sultans of Granada rich with their shimmering production, which was exported all over Europe and the Mediterranean. And all this is a mere sample of the work undertaken in the city. Studies of old records show over five hundred established occupations. It gives the picture of a bounteous, secure, diverse city, blessed with sun, water, and wit.

Where did they live? Along with the floral carmenes built throughout the countryside around Granada, their houses in the Albayzín were small, their rooms set around a courtyard, with a fountain in the center, flowers, or a grapevine. Off the courtyard on the ground floor were closets, a kitchen, and a storehouse with bins for cereals, beans, and fruit, and large jars, sometimes buried in the earth, for water or oil. Above, small bedrooms. It is a simple, beautiful order that asks light and air into the house all year, yet in the hot months holds enough shade to make for cool refuge. Here and there in the Albayzín, such medieval houses are preserved. A door opens, centuries fall away, and we enter a patio flanked by columns, with a small fountain in the center giving water into a channel that leads to a rectangular pool holding water for household use. Such a small space, proportioned sweetly, feels private, and yet at liberty, open to the sky. They are places of singular peace.

Houses had no place to bathe. But each part of the Albayzín offered public bathhouses, with steaming hot water, essential to public health and social concord. The ceilings of these bathhouses had star-shaped openings that brought slanting beams of light across the steamy air within. They were gathering places, places of refuge and tranquility, places to rest, swap tales, reflect. Especially among the Muslims of Granada, they were a cherished part of daily life.

What did they eat? It was, by the standards then and now, an unusually healthy diet. They ate oranges, wheat, dates, artichokes—in fact, the whole suite of fresh fruits and vegetables grown in the vega and on the hillsides around Granada. All this fresh produce, as well as lamb, and animals killed in the hunt, was sold in the humming markets of the city. As to their cooking, we read of simmered vegetable soup with toasted wheat, spiced lamb with onion and coriander, hot pies filled with two kinds of cheeses and coated with cinnamon sugar, chicken with pepper and ginger, and the use of mint, saffron, sesame, anise, mace, citron. The citizenry of all faiths, including Islam, drank wine; sanctions applied only to drunken and disorderly escapades. And for the love of heaven let us not neglect the desserts of the day: sugary quince tarts, pastries of blackberries and elderberries with honey, pomegranate syrups, almond cookies, cakes with rosewater and hazelnuts, cinnamon bread with honey and pistachios.

They dressed in loose clothes that visitors found fantastical and whose mellifluous names still hold their place in Spanish—almalafa (a full-length robe of wool or silk), zaraguelles (wide pleated breeches), pantufla (a soft, colored slipper), marlota (a loose, ornamented gown buttoned down the back). Many of the longer garments were hemmed in cloth of vivid color or, among the affluent, with gold thread to complement a showing of precious gems.

This period, from around 1000 to 1492—an extraordinary span of years—is of legendary accomplishment. For the Iberians, and for the later Roman and Visigothic inhabitants, this settlement had offered a pleasance, a place of safety, a place to work and invent and dream. Now the Albayzín made itself into one the best places in the world to live. It had fine fresh water and sunshine, newly fortified walls, the blessing of religious tolerance, flourishing gardens and fields, a rapturous tradition of poetry and music, and hard-working, exploratory citizens.

There were setbacks. One of them was so terrible, we must give it notice. In 1091, the city suffered the conquest of the Almoravids, a powerful tribe of new converts to Islam who originated in the area where we now find Mali and Mauretania. The Almoravids had risen to power in North Africa by astute, fanatic military aggression and had gone on to make their capital the city of Marrakesh. The rulers of the cities of Al-Andalus, militarily weak and threatened by the invasions of Christian kings from Northern Spain, appealed to the Almoravids for help. And help they did, doing battle with the invaders from the north, and even invading territory where Christians ruled over citizens of the three faiths. After their success, they turned viciously on their supplicants. Worst of all, in Granada, their persecution of Christians in the name of Islamic fundamentalism reached such an extreme that several thousand of them emigrated, under protection of a Christian army, to northern Spain. Such was the severity of the Almoravids that they even turned on the popular mystics of the day, the Sufis, and suppressed their schools and burned their books.

The population revolted at these oppressions, and a rival power, more tolerant and constructive, was invited in from North Africa. Called the Almohads, they possessed a formidable military prowess and were builders in their own right. Welcomed by the populace, they put an end to the depredations of the Almoravids, whose rule in Al-Andalus lasted only fifty-six years.

Here in the Albayzín, just below our house, rises a strong, lovely Almohad minaret, the bell tower of the church of Saint John of the Kings, even now being restored as the Albayzín, building by building, reclaims its heritage.

In 1238, the Almohads gave way to the first of the Nasrid kings, one Yusuf Nasr, of Granada. His quarters were in the Albayzín, and he and his descendants, through their political suppleness, improvisational diplomacy, and the sheer talent of their subjects, would keep Al-Andalus alive in the south of Spain for another two hundred and fifty years—longer than the United States of America has existed. The same year Nasr took power in the Albayzín, he began the last phase of building in Granada, the one known worldwide today. For across the way stood the Sabika hill, and upon that hill, Nasr determined he would build an entirely new barrio of the city. It would be full of gardens, and in the center would rise a new palace, the Alhambra.

It was an opportune time for the construction of a palace. During these centuries, as Christian armies slowly dismembered the reign of Islamic emirs and reconstituted Al-Andalus under Christian rule, gifted craftsman and scholars sought their place in society in one or another city. Some were welcomed and valued in Christian Spain; others were persecuted. And some traveled to southern Spain, to Granada or to its surrounding territories, to begin new lives. After five hundred years of progressive development in gardening, agronomy, architecture, poetry, philosophy, the natural sciences, and design, Al-Andalus had a preponderance of talent, whomever ruled the city in which they lived.

With its population and prosperity increasing, the city had grown. The Albayzín for many centuries was Granada. Over decades and centuries, from the early 1200s, the city spilled down the slope to fill the area between the Albayzín and the Genil River. And as the Alhambra and its environs rose on the Sabika hill, Granada and its surrounding countryside, full of carmenes, took on an iridescent beauty. We have travelers’ accounts, from a German traveler, Jacobo Munzer, in 1494, and from the Italian Andrea Navagiero, in 1526. It is worth the while listening to their voices.

First, Munzer:

At the foot of the mountains, on the good plain, Granada has, for almost a mile, many orchards and leafy spots irrigable by water channels; orchards, I repeat, full of houses and towers, occupied during the summer, which, seen together and from afar, you would take to be a populous and fantastic city . . . there is nothing more wonderful. The Saracens like orchards very much, and are very ingenious in planting and irrigating them to a degree that nothing surpasses.

And Navagiero:

All the slope . . . and equally the area on the opposite side, is most beautiful, filled with numerous houses and gardens, all with their fountains, myrtles, and trees, and in some there are large and very beautiful fountains. And even though this part surpasses the rest in beauty the other environs of Granada are the same, as much the hills as the plain they call the Vega. All of it is lovely, extraordinarily pleasant to behold, all abounding in water, water that could not be more abundant; all full of fruit trees, like plums of every variety, peaches, figs, quinces . . . apricots, sour cherries and so many other fruits that one can barely glimpse the sky for the density of the trees . . . There are also pomegranate trees, so attractive and of such good quality that they could not be more so, and incomparable grapes, of many kinds, and seedless grapes for raisins. Nor are wanting olive trees so dense they resemble forests of oaks.

Another writer, Bermudez de Pedraza, commented directly upon the Albayzín:

[The houses] were delightful, embellished with damascened work, with courtyards and orchards, beautified with pools and fountain basins with running water . . .

The Albayzín had reached some apotheosis it would never enjoy again. The mosque offered a courtyard full of lemon trees, and flowering trees found their way into the names of things. There was a “Mosque of the Walnut Tree,” a “Street of the Fountain of the Cherry Tree,” a “Promontory of the Almond Trees.” Up on the hill, in the area of the original settlements of los Iberos and the Romans, were public squares, a hospital, markets, hotels, warehouses, and the ateliers of silk spinners. In the lower part of the Albayzín was the legendary Maristan, a sumptuous building dedicated exclusively to the care of the mentally ill. The barrio as a whole was a hive, with labyrinthine streets so narrow you could reach across to a window on the other side. The minuscule branching lanes seemed infinite to travelers. Arches of stone stood over tiny streets, and tunnels linked some houses to one another. Balconies, sheds, rooftop gardens, and latticed windows set above cul-de-sacs all complicated further the layout of the barrio. Some quarters had their own gates, for closing off the neighborhood at night. The overall complexity of the place was such that Munzer thought it looked like a hillside covered entirely with swallow’s nests; though he found the houses clean, almost all with their own cisterns and plumbing.

The last competent Nasrid king, Muhammad V, died in 1391. He completed, following on the work of his father, Yusuf I, the construction of the Alhambra. The two hundred eighty-eight years from the arrival of the Zirids, in 1013, to the last of the Nasrids in 1391, offered a beauty of complex power. That beauty would suffer the torments history brings often to such a comely target. Yet the life force in the work done could not be extinguished. And we can learn from the story of the fall of Granada, its aftermath and dark detail.

INTO THE SLOW INFERNO

Late in the fifteenth century, in 1469, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castile made their famous marriage. It was not a century in which Granada had enjoyed prescient leadership. In fact, the most powerful families in Granada marked the century with treachery, the extermination of rivals, the revolt of sons against fathers, and other episodes of imbecility. All this destructive governance culminated in the sultanate of the ludicrous Boabdil, a onetime captive of Ferdinand who was freed to return to Granada. Ferdinand knew his man. For it was Boabdil who would bear down on Granada with the full weight of his fear and vulgarity and hasten the end of the city by his useless quarreling and confusion.

In 1491, Ferdinand and Isabel’s armies besieged the city and denied it the bounty of the vega’s agricultural lands. Granada was starved into submission. With famine increasing, a surrender was negotiated, on terms set down in what is known as the Articles of Capitulation, signed by the king and queen. They make splendid reading today for the express goodwill that shines there. Let us treat ourselves to four brief passages, from a document that is dead center in the history of Spain and of Europe:

3. Isabel, Ferdinand, and Prince Juan [their son] would after the surrender accept all Granadans . . . “great and small, men and women,” as their vassals and natural subjects. [They are] guaranteed to remain in their “houses, estates, and hereditaments, now and for all time and for ever . . . nor would they have their estates and property taken from them . . . rather they would be honored and respected.”

4. Their highnesses and their successors will ever afterwards allow the King, [civilian] and military leaders, and good men and all the common people, great or small, to live in their own religion, and not permit that their mosques be taken from them, not their minarets nor their muezzins . . . nor will they disturb the uses and customs which they observe.

21. Law suits which arise between Moors will be judged by their law . . . as they customarily have . . . but if the suit should arise between a Christian and a Moor, then it will be judged by a Christian judge and Moorish qadi, in order that neither side may have any grounds for complaint.

29. No Moor will be forced to become a Christian against his or her will . . .

These passages illustrate the tenor of the document as a whole, which reconfirms and extends the promises of protection for religion, property, and custom. It is a document wholly in the spirit of Al-Andalus. The Muslims were to be treated with tolerance and respect, in the present and for all time—such was the commitment of the sovereigns of Spain. It was as if Ferdinand and Isabel had looked carefully into the eight hundred years of Al-Andalus, under the administration of Muslim caliphs or Christian kings, both with the active and brilliant help of the Jewish community of Spain. It was as if they had studied the achievements of the past centuries in the arts, in poetry, music, science, and technology, and wanted just such energies in their own kingdom. It was as if they wanted to honor the accomplishments of the period and the wisdom of their own Christian forebears. In reading the Capitulations, one wants to salute the genius of two intelligent rulers, who at their moment of triumph looked into the past, so as to provision their nation for the future.

Even today, one can walk around the Albayzín and imagine the hope that must have arisen in these streets. A document full of justice, noteworthy for its fairness and decency, issued directly and personally by the monarchs, now guaranteed for all time the continuance and thriving of Al-Andalus, medieval Europe’s culture of genius.

Ferdinand and Isabel lied. It was a lie of such horrific grandeur that we live today with the consequences. An important clue to the lie was in the one discordant note in the Capitulations:

48. The Jews native to Granada, Albayzín . . . and all other places contained in these Capitulations, will benefit from them, on condition that those who do not become Christians cross to North Africa within three years counting from December 8 of this year.

Isabel and Ferdinand formally took possession of the Alhambra on January 2, 1492. In their new palace, they set to work immediately and in secret to draft an Edict of Expulsion for the entire Jewish community of Spain. It was completed swiftly and signed on March 31, 1492. The edict was withheld for a month, then was proclaimed publicly in Granada and throughout the country. The Jewish quarter in Granada was to be demolished immediately. The Jews, all of them, had three months to leave. All of their assets that could not be carried had to be sold. Family houses were bartered for an ass; vineyards for a piece of cloth. Even in the case of a sale, the Jews were forbidden to take into exile any gold, silver, or coined money. What is more, the Edict of Expulsion went on to say that, after the three months, if any Christian “shall dare to receive, protect, defend, and hold publicly or secretly any Jew or Jewess,” then he would forfeit the entirety of his wealth, possessions, royal grants, and inheritance. These absurd conditions effectively transferred the preponderance of Jewish wealth to Christian hands. If they had wealth remaining, they were systematically robbed of it, by means of extortion rackets, embarkation fees, looting of concealed assets, or cancellation of debts owed them. At sea, pirates awaited them, and in North Africa, they were attacked and sometimes enslaved.

To avoid such confiscation, there were, of course, numerous conversions, as there had been in the decades previously. But the edict achieved its goal: Isabel and Ferdinand wiped out the oldest and most talented Jewish community in Europe, and one of the foremost in world history. And they did not rest content with such destruction. The Muslims were next, and the action was in the Albayzín.

The respect for Islam and the protection of property granted the Muslims was for “. . . now and for all time and forever.” All time and forever turned out to be seven years. But for the Muslims, those seven years gave them hope. Hernando Talavera, the archbishop of Granada, and the count of Tendilla, the mayor of the city, worked with tact and dedication to see the Capitulations honored. Talavera, though a vitriolic anti-Semitic propagandist, thought that the visible grace of Christian practice would lead, in the long term, to the voluntary conversion of Muslims. He even counseled his priests to learn Arabic. There were disquieting signs, though. Especially the policy to isolate Muslims in their own neighborhood. If they lived in other parts of Granada, they were forcibly moved to the historic Albayzín, and the Christians there moved elsewhere with royal assistance. Ominously, this separation of non-Christians into their own ghettos had been the policy, slowly enforced, of Ferdinand and Isabel for over two decades.

Replacing Talavera in 1499, Cardenal Ximenes de Cisneros, confessor to Queen Isabel, had other ideas. Cisneros had been a key negotiator, in 1497, for Ferdinand and Isabel in the marriage contract between their daughter and the king of Portugal, Manuel. Portugal, like the rest of the Iberian peninsula, had at the time a well-established Muslim population. It also had the only remaining Jewish population in the Iberian peninsula. But the king and queen of Spain, with Cisneros as one of their key counselors, had a plan. As a condition of the marriage, they forced Manuel to promise not only to expel the Jewish population, but—and this was unprecedented—the Muslims as well. The terms of the expulsions we may recognize. The Jews had to leave by a set date, they could depart only from Lisbon, and those who did not meet the deadline were enslaved. Yet there was a further condition: the authorities forbade the children of Jewish families to depart with their parents; the children were to be seized and taken away to be raised as Christians. As to the Muslims, they were forced, in an astonishing and diabolical turn, to move to . . . Spain! An exit fee was required, of course. We shall see the fate prepared for them, to which preparation Cisneros now devoted himself.

Ensconced in the Albayzín, Cisneros first distributed rich gifts to Muslim leaders, to encourage conversion. When the results did not satisfy him, he made it known that Muslims who did not convert would risk imprisonment and torture. The reaction was what we would expect: despair, disbelief, an incendiary atmosphere in the barrio.

Cisneros meant what he said. For he was not in Granada simply to help in the spiritual administration of the city. He was there as part of a powerful religious institution, invested with rampant new power by Ferdinand and Isabel: the Supreme Council of the Inquisition. Archbishop Ximenes Cisneros was Inquisitor General.

Cisneros was to go on to play a most prominent role in the government of Spain. He was a man of cunning, martial zeal, torrid Christian conviction, and dark political genius. His central tenet was simple: the Catholic church, bearing the teachings of a divine Jesus, must save the souls of Muslims and Jews by forcing their conversion and exterminating their culture. He rejected Talavera’s interest in Arabic and the printing of prayer books and hymnals in that language; “pearls before swine,” he called it.

Because the Articles of Capitulation were so clear, Cisneros needed room to maneuver; that is, he needed to work as a provocateur. He proved to have a demonic gift for such initiatives. The Capitulations, for example, provided that women with ancestors who at any time were Christian could be questioned in the presence of witnesses. The idea was to induce them to return to Christianity. Cisneros, accordingly, sent agents, including a man fatefully named Barrionuevo, into the Albayzín to seek out the daughters and wives of Muslim families, on the pretext of advancing such questions. The families of the Albayzín viewed such actions as a violation of their honor and a transparent attempt to seize women for forced conversion. In one such incursion, Barrionuevo seized a young woman in the plaza (now called the Plaza de Abad) between the mosque and the hospital. She called out for help to those around her; a crowd gathered, freed her, and then turned on Barrionuevo. He was known to be an agent of the hated Cisneros, and he was seized and killed. Cisneros, when he got wind of the uprising, hid himself in another part of the Albayzín (in a place now called the Hospital de la Tiña), within the most fortified section of the barrio. When the fierce archbishop made his escape, he had what he wanted: a pretext for ethnic cleansing.

He commenced with that centerpiece of hatred, the book-burning. Cisneros ordered the confiscation of all copies of the Koran, including private copies looted by priests and soldiers from residents of the Albayzín. To this haul he added most of the contents of the Madrasa, which served as a kind of university library in the center of Granada. Cisnero’s associates went on, in addition, to seize any religious tract, including the exquisite stories and poetry of the Sufis. Many precious manuscripts with beautiful borders and classic calligraphy, plated with gold and silver, were added to the pile in the lovely Plaza Bib-Rambla, near the central marketplace and by the side of the most famous school in the city. There, Cisneros had all the books incinerated. It amounted to more than five thousand volumes, though some estimates are astronomically higher. It was the first major book-burning after the surrender of Granada, that is, in newly Catholic Spain. But far from the last.

Some anguished residents of the Albayzín emigrated immediately. Some joined a revolt in a beautiful valley, the Alpujarras, high in the mountains above Granada. Ferdinand himself commanded the Christian troops, and one of his companions in arms, one Luis de Beaumont, in a battle near Andarax, in the eastern Alpujarra, took three thousand prisoners. He slaughtered them all and went on to blow up a nearby mosque with six hundred refugees, children and women, inside. These massacres soon were known throughout the Mediterranean. The revolt in the Alpujarras was put down in two bloody years.

The Muslims of the Albayzín, under constant pressure, with some of their numbers threatened, imprisoned, or tortured, began to convert in large numbers. By early 1501, there was hardly a Muslim left. The culture, eight hundred years old, of course remained, with its public baths, distinctive dress, culinary specialties, and its gift for music and love of dance. And because the conversions were forced, many Muslims were only nominal Christians. In the Albayzín, many families carried on their traditional way of life.

In the same year as these forced conversions, Ferdinand and Isabel issued another edict that required the Muslims of most of the rest of Spain, specifically in Castile and Leon, to become Christians or go into exile. The rules that applied to exiles had the usual malignant absurdity: they had a year to leave. They could take their possessions, but no gold or silver. The exiles could not go elsewhere in Spain, nor to North Africa, nor to any territories under control of the Ottomans. They could go, then, to Egypt. But they could only sail to Egypt from the Bay of Biscay, in the north of Spain. Unfortunately, almost no ships sailed to Egypt from the Bay of Biscay. Why would they?

It was a program to force a final round of conversions. The efforts of Cisneros in the Albayzín had proved to be a deliberate test run for all of Spain. Since the fall of Granada had completed the conquests of the Christian armies, Granada had tremendous symbolic resonance. Accordingly, the Albayzín, historic center of the city, with its concentrated Muslim population, had been dealt with first. Now, in the following years, Ferdinand, Isabel, and their successors issued a further series of proclamations. Let us list a range of them, with a view to seeing the progress of the royal will:

1502: Edict of Conversion: all Muslims must convert to Christianity, or go into exile; Muslims remaining in Spain are to be enslaved. Muslims are made subject to the Inquisition.

1511: Moorish converts forbidden to bear arms or carry knives. All books in Arabic are to be surrendered; those having to do with Islamic law or religion are to be burnt. Tailors were fined for making Moorish clothing; butchers who prepared meat according to Islamic practice (called halal) could have their property confiscated. Property could not be passed to children in accordance with Islamic law, nor could former Muslims sell their property.

1526: The Edict of Granada: complete prohibition of all customs of Moorish life. All Moorish baths outlawed and closed. The owning of slaves, the wearing of any Moorish clothing (even amulets), the dyeing of hands with henna, and the circumcision of infants is forbidden. In exchange for a payment to the Crown, open abuse of Moors in the street and random sacking of their houses is to stop. Principal Andalusian office of the Inquisition moved from Jaen to Granada.

1565: The Synod of Granada: all previous royal edicts confirmed. All aspects of Moorish life forbidden: baths, Arabic books, social ceremonies linked to Islam, traditional rituals such as fasting, and Moorish music and dancing.

So the expulsion in 1492 of the Jewish community of Spain was a prelude to the extinction of the Muslim community. The goal was to tear out the culture—its religion, customs, traditions, ceremonies—by the roots. The means were royal decrees, close surveillance, harassment, humiliation, confiscation of property, imprisonment, torture, and capital punishment. We read, for instance, of people beaten and jailed for not attending church, of Moriscos (that is, Muslims who had been forced to convert to Christianity) being coerced to drink liquor and eat pork. And the Inquisition was fighting, all this while, for exclusive power to enforce the edicts. It was a power they would use with methodical gusto.

This attempt to eradicate a whole culture proceeded by fits and starts. The Moriscos paid bribes, maneuvered, cultivated powerful friends, and continued to make a crucial contribution to the economy of the city. These men and women, after all, were now all Christians. So they, in theory, were asking only for respect for their centuries of cultural heritage, since their religious heritage had already been abolished. The partial success of these efforts by the Moriscos explains the need, on occasion, to confirm the royal edicts.

But confirmed they were. In the course of the 1500s, the power of the Inquisition increased. And the doctrine of limpieza de sangre—blood purity—took on a central and defining importance. At the same time, the Morisco community’s knowledge of horticulture, irrigation, silk-weaving, construction, and commerce seemed less crucial, given the weighty current of gold and silver arriving from the New World. By 1567, in the Albayzín, the newly confirmed edicts began to be enforced without mercy. This time, no payment to a high official, nor any political deal, nor any advocacy could help. Rumors circulated that children of Moriscos would be taken from their families. The Albayzín churned with rumor, terror, bitterness, despair. The Moriscos assembled secretly, seeking a way to resist. Apocalypse was in the air. Such mad foreboding is almost always wrong. But not this time; soon, apocalypse was on the ground.

The Morisco community in the Albayzín, along with Morisco settlements in the Alpujarras, planned a campaign of armed resistance. Cautious souls voiced strong arguments against such a rebellion, but a doomed plan took form. By the end of 1568, the community, as though driven insane by seven decades of broken promises, confiscated property, forced conversions, book-burnings, and secret trials of the Inquisition, finally revolted and began a war that was to last two years. Called the Second Granada War (1568–1570), most of the fighting was in the Alpujarras, where the Christian armies, heavily armed and with pathetic, fractious leaders, fought mobile bands of Moriscos, poor and disorganized, with their own pathetic, fractious leaders. There were repellent massacres on both sides before the might of the Spanish military prevailed.

The Albayzín stood no chance. It was the biggest Morisco neighborhood in Granada. Granada symbolized the final conquest of Spain by Christian armies, and the city served as the center of power and religious authority for the whole region. In March of 1569, the authorities massacred all one hundred and ten Morisco prisoners held in the prison at the base of the neighborhood, near Plaza Nueva. Later that year, soldiers entered the Albayzín and tore it to pieces. There is no other way to say it.

Two companies of soldiers entered Plaza de Abad, in the heart of the barrio; another five hundred soldiers circled the neighborhood. In the attack, the troops entered and looted houses, then wrecked whatever was left of them. They plugged or poisoned the fountains, water troughs, and famous aljibes. They pillaged stocks of grain, destroyed the market stalls, stores, workshops. In the autumn of 1570, they seized all boys and men between the ages of 10 and 70 and imprisoned them in the churches, then later in a hospital. In total, the count of prisoners was about 4,000. Contemporary accounts record the scene:

It was a miserable show, to see so many men of different ages, with heads bowed, hands crossed, faces washed in tears, their demeanor wretched and sad, since they were leaving their cherished houses, their families, their way of life, their farms, and all the good that they had . . .

. . . they had only the most terrible lamentations, having known prosperity, the fine order and pleasure of their houses, carmenes, and orchards, where [they] had all their recreations and amusements, and within a few days they had seen everything laid waste and destroyed, for matters had come to such a bad end, that it seemed a good thing to subject [their] most happy city to just such destruction . . .

The Spanish army marched these men out of Granada and into the winter of 1570. Forcibly exiled, and now scattered around the country, mostly within Castile, we lose sight of most of them. We know that hundreds of them died of exposure on the forced march to their new towns. Of the fate of their wives and children, we know little, except that the youngest passed into the service of the so-called “Old Christians” of Granada.

In 1571, royal agents visited the Albayzín to inventory the houses and goods that remained, so that they might be formally confiscated and given to Christian families. They found, out of the many thousands of houses on this hillside, less than three hundred occupied. The livelihood of the workers lay buried in the rubble. The authorities had tried to keep in the barrio workers with knowledge of silk-weaving, orchards, and the water systems. Of the rich scope of skilled professions that had for so long enriched Granada, little remained. The birth rate, measured by baptisms, plummeted. And whatever the enticement offered by the Crown—the gift of confiscated houses, cheap rents, and the like—there were few takers. The population continued its decline, from its high in the 1400s of around forty-five thousand to twenty-seven thousand in 1561, then, after the sacking of the barrio, falling disastrously. Some observers of the time doubted the survival of the Albayzín.

KING SOLOMON COMES TO THE ALBAYZÍN

But then in 1595, at the edge of the barrio, came an event so improbable that it is small praise to call it a miracle: a discovery that bid fair to make Granada into a worldwide center of Christian pilgrimage and worship, and at the same time bring Christian practice into closer alignment with the worship of Allah.