A Few Notions of Geometry and Revelation

FROM THAT LONG-AGO night of rain, when we walked with dog and baby to our rubble-strewn house, after the months of construction as our life took form here, we came to live with books and conversation, red wine and ebullient company, the music of Spain and mood of the Albayzín, languorous and celebratory at once. And we lived with a castle in the sky before us, the Alhambra. It floated there as improbably as a fortress in one of the fantastical tales we read to Gabriella every night. The terrace off our torreón looked straight toward the castle, and each night, it seemed a conjuration. I was never sure, when we went to bed, if it was still going to be there in the morning.

As a hive holds cells of honey, so does the Sabika hill, rising before us across the canyon of the Darro, have a history of holding constructions of the most intricate beauty. After looking into the history of our neighborhood, we were hardly surprised to find that the Alhambra has one of the city’s most bizarre stories. In 1492, after Granada was starved into surrender, Ferdinand and Isabel used it as their own, with Isabel swishing around in gorgeous Arab robes. Then, after their departure, the palace began to disintegrate all through the early 1500s, even though the despised Moriscos were forced to pay tribute to maintain it. As the Inquisition and ethnic cleansing lay waste to the Morisco community, the tribute began to fail, and in 1571, Philip II decided to direct some of his income from sugar cane works near Seville to pay for repairs. Still, in 1590, part of the palace burned down, and as the years rolled on, the governors of the barrio and the palace cast about, rather wildly it seems, for ideas to use the space. So, noting the beautifully tiled chamber where ambassadors to the court of Granada were once received, they decided that it would make an superb ammunition dump.

So it remained for decades, until in the early 1700s a new Philip, this time the Fifth, decided that the palace and its royal district no longer needed its own governor, with his noisy band of servants. So he dismissed him. This governor, a duke who liked the palace and the servants, wanted to depart with a flamboyant gesture, so he burned down his fabulous residence.

A good deal of the royal barrio lay now in ruins, but one group with canny temperament and a good eye for real estate moved in: the gypsies. So, a bit more than two hundred years after the conquest of Granada, a gypsy encampment thrived in the palace of the sultans and of Ferdinand and Isabel. Visitors, of course, thought it picturesque to have donkeys and guitar-strumming gypsies wandering with them through an august and crumbling ruin.

But the dedicated administration of Spain and Granada were not done exploring how they might use the palace and its grounds. As the 1700s went their way, the palace looked like an ideal place for a military hospital—it was dirty, but it had big rooms and nice views. Then the governor of Granada, musing perhaps on the fine time his predecessor once had, decided that he, too, would move right in and sport about in the ruins. The palace still being full of incomparable woodwork set into geometrical patterns as complex as the tile work, the new resident governor began to rip it out and use it for firewood. Wanting to have his milk and meat close at hand, he also set his farm animals to roam throughout the complex, adding another complement of animal droppings to the already rich mix. And even then, the ingenuity of city officials had not exhausted itself, for the rooms where dwelt once the wives of the sultan were selected as the ideal venue for the salting of fish.

In other words, the palace complex came to look rather like the Albayzín of the same period: a ruin full of gypsies. Through the monument, animals wandered, and moss found a foothold among the trash and weeds. Virtually no one thought that the extraordinary Albayzín would survive, and by all accounts, the legendary palace of the Alhambra was turning into rubble and dust.

As the centuries wore on, the reputation of the Alhambra, as though by strange radiance, came to penetrate most of Europe, because of the fictional flights and visits of the English, Americans, and French. They used the palace as a basis for fantasy, with full doses of sexual intrigue, genies, tragedy, and frothy romance. Let us roam over a few centuries and look at the names of some of the writers and composers who treated us to fantastic stories of the place: in 1672, the English poet John Dryden wrote a play about the conquest of Granada; in 1739, the French composer Joseph Pancrace Royer wrote a famous ballet about the sultan’s amorous wife, who met her lover for secret couplings in the rose hedges. Not to be left out, in 1829, Victor Hugo published a long, over-the-top poem on the same subject, called “Les Orientales,” full of genies and exclamation marks, and in the late 1800s, Claude Debussy wrote two moody pieces about Granada and the gates of the Alhambra. All these writers and composers over several centuries had one astonishing thing in common: not a single one of them had ever been to the Alhambra, nor to Granada, or even anywhere nearby. Even the twentieth-century Spanish composer Manual de Falla, who eventually lived near the Alhambra, went right ahead and wrote music about the gardens there, well before he ever visited them.

Fortunately, other writers, scholars, and composers did visit, and it is partly to their work that we owe the unlikely preservation of the Alhambra. In 1840, the 19-year-old French poet-to-be Theophile Gautier sauntered straight in to the Patio de los Leones, cooled his wine in the fountain, and bedded down for the night. But two other nineteenth-century visitors changed the history of the whole palace: in 1829, the American diplomat Washington Irving, and in 1832, the Welsh scholar Owen Jones. Irving’s writings, The Tales of the Alhambra, is still in print and sold all over Granada today. Jones’s masterwork, Plans, Sections, Elevations, and Details of the Alhambra, a book to which he gave his life and his fortune, was scientific, accurate, and magnificent. Published in the years 1842–45, it contains reproductions of most of the Alhambra’s ornamental tile and plaster work. Even to produce the books, Jones had to work a revolution in the art of color printing, until then poorly developed. The books are unprecedented in the history of design, and they gave the Alhambra to the world irrevocably.

At the heart of the gift given were faithful renderings of a sacred art unknown in the West: the art of ceramic tiles with complex geometric designs. In the Alhambra, such tiles cover wall after wall. In our years in Granada, these tiles have been our companions and our teachers. In them we find an example of how the beauty of another culture may be a mentor to understanding and a map that leads onward to the most surprising joy.

I can remember, when in college, seeing for the first time a photo of one of the tiled walls of the Alhambra. Though I had the most complete ignorance about their nature, I was spellbound by the fierce, lovely complexity of form and wondered what on earth could be the basis of it. But it was not until we moved to the Albayzín that I had the time, because of our many visits to the monument, to study in peace the tile work. They offered an undiscovered country. I had long hoped to visit and learn there, though it was a place so beautiful I did not know if I could return with my story.

So let us begin. It is a story that begins two millennia ago, though we can tell it in a few pages. Just as our garden had an ancestor in a garden of the sixth century BC, so do the tiles of the Alhambra have an ancestry in southern Italy, in the same century, in the teachings of Pythagoras, a figure so important that almost nothing is known about him. We know he was born on a Greek island, traveled through the Near East, and settled in southern Italy. There, he did something rare: he wrote nothing but lived so as to exercise an extraordinary influence on mathematics and philosophy. Many tales are told about him, including two wonderful declarations: that he could be in two places at once, and that rivers spoke with him.

What is important for us is that Pythagoras thought that the world offered a beautiful order, and to learn that order, we had to study number and proportion. If we did so, then we had a chance to come into possession of a key to learning our place on earth, and the real purposes of life. This core idea, that numbers have both a practical and a spiritual use, goes along with another idea of Pythagoras: that the soul is immortal and may dwell in another world with forms of goodness that are permanent. Recall that Homer consigns the soul after death to Hades, a dismal world of regret and lamentation, which Tiresias the prophet calls “a joyless place” and which even Achilles trashes unforgettably, saying that he “would rather be above ground still and laboring for some poor portionless man, than be lord over all the lifeless dead.” Compared to such a destination, the notion of Pythagoras held a lustrous promise.

Though his central idea has undergone strange adventures through the centuries, it is simple: that beyond doctrine, belief, and ritual, beyond habit and appearance, there exists a durable world, an objective reality we can understand. One of the primary means to such understanding is number. That is to say, numbers are not only essential to our life on earth, they also are our introduction to another world of understanding, one based on an order deep within us and natural to our experience. So, for example, we have in our lives the sun, the moon, the stars, each of them with its own movement through our day and night. Yet this movement is not random, but harmonious and comprehensible, and susceptible to description with numerical formulas. Similarly, with the playing of music. For instance, musical order created by vibrating strings turns out to be related directly to numbers. This discovery, attributed by tradition to Pythagoras, provided a foundation for the making of musical harmony. It works like this: if you take a string of given length and pluck it, the sound produced is called a unison, or fundamental pitch. Now, if you divide the string into two equal parts and pluck it, you hear a higher note: exactly one octave higher. If you divide the string into two parts, in a ratio of 2:3, the sound produced is called a perfect fifth; if the ratio is 3:4, then the sound produced is called a perfect fourth. So these orderly sets of sounds are precisely related to ratios among the first four whole numbers.

Music and number have a natural, powerful relation. In the legend of Pythagoras, this relation led to one of his most durable ideas, that of the música mundana, or the Music of the Spheres. The whole notion of numerical harmony is extended into the sky. Just as the movement of a certain length of a string produces a given musical tone, so the movement of the each of the planets produces, according to its distance from earth, a extraordinary musical tone. And taken together, the movement of the planets makes a music so beautiful that it is present everywhere and always, and so powerful that it governs the rhythms of nature. It is a harmony within life, the very music of creation. It is said to be the music heard by Moses when he took up the tablets on Mount Sinai. It is said to be the music we hear as we die, a prelude to our entry into a world beyond time. We may, as we live, hear this music ourselves, and make a life in concord with it, but we may do so only by uncommon learning.

Plato, Euclid, and many of the astronomers and scientists of classical antiquity incorporated these ideas and added a host of others in the flowering of mathematics that began in classical Greece and continued through the Hellenic period, building a significant body of knowledge that lay in manuscripts and practices throughout the Mediterranean, but especially in the libraries of Alexandria and the Middle East. With the sacking of Rome in 410 and the beginning of the Middle Ages in Europe, these writings fell into disuse, and their collection and study would wait until the eighth century, after Islam had carried its faith throughout the Mediterranean. As it formed stable governments and centers of study, its scholars took up the scientific and philosophical heritage of antiquity and enriched it with their own labors and discoveries. The center of these efforts, in Baghdad during the reign of Haroun Al-Rashid, was called the House of Wisdom.

Among these workers were an anonymous and brilliant group of writers known as the Brethren of Purity, whom we have met when we visited the translation school of Alphonso the Wise. The Brethren, in their labors, helpfully decided to summarize all knowledge in a single book. The book has fifty-two chapters, and the first three take up, respectively, number, geometry, and astronomy. As to the necessity of number in our efforts to find the truth of things, the Brethren say boldly: “the science of numbers is the root of the other sciences, the fount of wisdom, the starting point of all knowledge, and the origin of all concepts.” In geometry, according to the clear propositions of the group, we can relate number and form and create figures that exist in our minds, which gives us a way to begin to understand a durable, intelligible world beyond our senses. In this way, they claim, we can begin to build for ourselves a life in concord with a freely offered and permanent order within the world. As to astronomy, the Brethren, who revered Pythagoras, wrote of the wondrous harmonies of the Music of the Spheres, which by their account resounded according to measure and melody, ringing now like struck brass, then playing like some celestial lute. This is the music that is perfect, which we might imitate on earth, so as to be able to hear and remember in our own music the very order that informs all the visible world. In this way, sensual experience leads naturally and inevitably to stability and luminosity of mind.

There are other fascinations in the writings of the Brethren, not least their intense focus on the heavens as they relate to the ascent of our souls toward the divine. They wrote of the several spheres of the heavens, corresponding to the seven visible planets. And, as though they were giving patient instruction to Dante when, more than three hundred years later, the poet worked out his plan for the Paradiso, they detailed the way the soul must pass through each of the spheres to reach its destined fulfillment.

These ideas we have sketched—from Pythagoras through Plato and the scientists and translators of newly emergent Islam, culminating in the summaries of the Brethren of Purity—these ideas form the context we need in order to understand the beauty and meaning of the tiles that grace the walls of the Alhambra. The craftsmen who made them were working in a culture in which many of the distinctions we take as given—between science and art, sense and spirit, quantity and quality—were not rigidly established. And so we have in the tile work of the Alhambra, and the tile work throughout the Middle East, an example of an art based on geometry. It is an elaborately sensual creation with spiritual meaning and a work of precise quantities that we are meant to use, as we gaze, to refine the quality of our perception.

We have been voyaging through the centuries, just to do a simple thing: to stand together before a wall of tiles and say of what we see in them. Before we do so, we have to talk a bit more about number: specifically how, in the current of reasoning we have been following, the first few whole numbers relate to the earth, to the heavens, and to the sacred. We need to try to see the force field of associations bound up with these numbers. We need to see, beyond quantity, what they mean when we relate them to our experience on earth. To take up this subject means to venture into domains of thinking and experience that some might call mystical. But it is, in fact, a plain and practical endeavor, neither remote nor fanciful. It is based upon the simple proposition that to approach the sacred, we do not need religious institutions, a system of belief, doctrines, training, ritual, dogma, theology, or faith. What we need is love, study, and understanding. What we are trying to understand are the workings of beauty in tile work meant as a delight to the eye and as an embodiment of the sacred.

We need to start with the idea that numbers mean something, that the first few whole numbers have profound associations with our daily life and spiritual experience. These associations give us the grounding we need to look at the tiles.

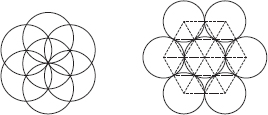

To begin with the number one: it is the number of unity and refers to the divine, to what is original, complete, perfect, undivided, and whole. It includes all life and both the material and spiritual world; it holds both our origin and our destiny. It corresponds, in other words, to the fundamental conception of sacred power in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In geometry, the symbol of unity is the circle, which from an invisible center traces out the perfect form from which all others can be derived. From the circle, craftsmen were able, with a kind of ecstatic improvisation, to work out the myriad shapes and patterns found in the walls of tile in the Alhambra and throughout northern Africa and the Middle East. What is more, the conception of beauty historically has, in many cultures, been bound closely with the very notion of unity embodied in the circle. When we encounter beauty, it is at its best radiantly inclusive, showing the connections among things, the resemblance and joinery of things, bringing together gracefully what seems separate—man and woman, mind and body, earth and heaven, human and divine.

Next, the number three: this number which, long after the composition of the Old Testament and the life of Jesus, became so central in Christian theology. It calls to mind the three celestial bodies most bound up with human life, the sun, the earth, and the moon. It contains as well the way the essentials of our lives are naturally understood in groups of three terms: say, lover, beloved, and love itself; the knower, the known, and knowledge itself; the perceiver, the perceived, and perception itself; and of course birth, life, and death. What is more, the number three, in the mysticism of the religions of the convivencia, marks our threefold motion: we descend from a divine and original world; we become part of a material and sensible world; and then, with work and knowledge and love, we rise again to a perfect world whence we came. In geometry, when a circle is twice reflected and extended outside itself, then as the reflection is completed, we have the first polygon, the triangle, which is the very first way we have to enclose space within lines.

From this figure, many other forms in Islamic tile work are derived. If we take two triangles together, we get a central symbol of Mediterranean spirituality, the six-pointed star, which refers to the very motions of descent, incarnation, and ascent described, the simple pattern of a personal journey.

The number four summons for us the elemental division of every year into four parts, since by the motion of the earth the sun seems to move south and north along the ecliptic. Twice during the year, at the vernal and autumnal equinox, the day and night are of equal length, and at the winter and summer solstice, we have our longest night and longest day. This fourfold division of the year gives us the traditional way to mark the seasons and refers as well to the ancient quartet of earth, air, fire, and water, as well as to cold, heat, wet, and dry, and to the four cardinal points of the compass. Four was also a key number for the Pythagoreans, who associated it with justice, perfection, and the nature of the soul. The square is easily inscribed within a circle, by locating four equidistant points. Also, if we continue in our reflection and extension of circles, so that the originating circle is itself encircled, a square emerges.

The number five is especially bound up with each of us because we have five senses to connect us with the world. In the mysticism of the Middle Ages, as it was found in the Middle East and in Spain, our five senses do not show us a real world, but introduce the world. That is, our five senses may be developed into a further set of five capacities, more subtle and powerful, so that we may learn to see things whole and true and act with more insight and prescience. With full development of such capacities, a man or woman will have a direct, creative, and conscious connection with a divine order that shows itself on earth. In geometry, we invoke the number five with the pentagon, which we can inscribe within a circle using only a compass and straightedge. The pentagon has remarkable qualities, since if we connect its vertices, we create a beautiful set of pentagonal stars. The ratio of the side of a pentagon to the diagonal of a pentagon (that is, to each of the sides of the star) gives us the golden ratio, identified with beauty throughout history. The golden ratio is found not only in the human body and in beautiful human creations, but also everywhere in the natural world—in nautilus shells, in sunflowers, in pine cones, even in the play of light. So are patterns of growth and movement in nature related directly to geometrical ratios and the integration of mind as we seek to understand our place and purpose in the world.

What we are sketching here are cumulative, vital associations with the first few whole numbers. They are essential to understanding the tiles of the Alhambra, since the design of the tiles holds a meaningful pattern, and what it may mean is bound up with numbers. A sense of the meaning of numbers, along with rules of numerical order, ratio, and harmony, were used to create the patterns of the tiles.

Let us move on to the fine prospects afforded by six, seven, eight, and twelve.

As to six, it is an essential quantity in geometrical design because of its connection with the circle and its perfections. If we, from a point, inscribe a circle, and reflect that circle outward, we find that six circles, only and always six, will fit around the circumference. If you connect the center points of the surround of circles, you draw a hexagon that mirrors and encloses the first. If you draw lines to connect the vertices of the hexagons, you get the six-pointed star that is a symbol of perfection in the religions of the convivencia. Of course, in all three religions, God created the world in six days, and rather than take this in a brute, literal sense, we might see it a statement about the way form is conceived in the mind and expressed in the world. So the center point of a circle, from where a circle is created, corresponds both to origin and to completion, both the invisible source of things and the still point—call it the day of rest—after form is brought forth.

To state this again: the center point gives rise to the first circle, then to six reflected circles, which gives us the hexagon. The hexagon holds the six-pointed star, which portrays by tradition our journey from our origins, to earth, followed by our ascent once more, after our life and learning here.

The center point and the inevitable hexagon, together, bring us to seven, especially rich in associations. It is three plus four, and so incorporates by reference the three stages of the journey, and, as well, the number that refers to the earth, its seasons, its cardinal points, and its essential components. What is more, it represents the ancient idea of the seven heavenly spheres and, as we saw, the six days of creation and one of rest. Seven is also one-quarter of the lunar cycle, which is the basis for the rhythm of work and rest worldwide. If we multiply three and four, we have twelve, another emblematic number in the faiths of the convivencia, showing up in the twelve disciples of Jesus, the twelve “pure ones” of Shiite Islam, and of course in the traditional division of the sky into the twelve signs of the zodiac. Even today, we live with these concentrated references, in the modern division of the day into twice twelve hours. One more harmony; if we add the numbers from one to seven, we have twenty-eight, the number of days of the complete lunar cycle. To bring things back for a moment to the Albayzín, it is the number of aljibes that brought fresh water to the barrio; it’s as though the Albayzín wanted to make a gesture of affection and recognition to the night sky.

One last set of associations, this time for the number eight. Eight is the double of four, which is associated with the earth. When it is expressed in the octagonal star (a square rotated one-eighth turn upon another square), it is a beautiful image of the turning earth and of the movement of life. Within the octagonal star is a perfect octagon, which throughout Christendom is the shape used for the baptismal font. It signifies spiritual rebirth, since Jesus rose from the dead on the eighth day of the Passion. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus speaks of the eight beatitudes. In the Kabbalah, eight is the number of transcendence. Eight, as the next number after emblematic seven (the heavenly spheres and the week of Creation), represents the domain of fixed stars: an especially rich association, given the plentitude of stars in the tile work we will shortly have before us. It is the step beyond the created world, to the re-creation of ourselves in a domain of light, the step from the life created for us to a life in creation. To put it another way: eight is the number of matter becoming spirit. Because of this, eight in many cultures is an auspicious number. In the Koran, there are eight forms of paradise, and eight angels carry the divine throne. It is worth mentioning that this linkage of eight to spiritual practice is worldwide: witness Buddhism with its eightfold way. Even in China, Taoism has eight immortals, and there are eight pillars of heaven. Closer to home, and directly relevant to the Alhambra, the octagon is the preeminent symbol of the Sufis, said to hold the wisdom at the source and confluence of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

Now, having in mind all this heritage, let us walk into the Alhambra, and into the throne room in the Tower of Comares. Above us, we see a ceiling of inlaid pieces of wood, over one thousand eight hundred of them, in seven circles marked by myriad stars. From the four corners of the room, four bright channels run, marking the course of the four rivers of paradise. They run to the center of the concentric stars at the highest point in the ceiling, the source of creation and its final destination. Around us are walls of iridescent tiles, each wall with its own design. Let us choose one to study and look into the world of number and form and see where we are led by the play of mind made available by an art meant to offer us a kind of treasure map for meditation.

It is just beside the entrance of to the throne room, a modestly sized panel. Let’s look at it carefully together.

The tiles fit together seamlessly. It looks as if the wall is in movement, which is an effect found throughout the Alhambra. The solid wall pulses with the energy of form. At the heart of this panel is an golden octagonal star, bounded by white lines, which create another octagonal star, which in turn unfolds into a larger, green octagonal figure. This beautiful design is surrounded in turn by eight golden figures, each with five points, and in form like human forms with arms outstretched, as if they were dancing. Then, as we look at the tiles, we find the central octagonal star reproduces itself, as eight deep blue octagonal stars, arranged symmetrically around the golden figures. If we refocus and try to see the center section of the design as a whole, we notice that the white line surrounding them makes a perfect octagon. After a moment, we can hold both the center octagonal star and the surrounding octagon in focus, so as to see both the centerpoint and its frame.

This is a good time to pause. For just with this one initial exercise, we have had to experiment with our vision, to change our perspective on the design, to see what is figure and what is ground. This figure-ground switching, commonly found in optical illusions, here is deliberately urged upon us, since crucial elements of the design remain concealed unless we refocus our attention to select another set of elements. But this skill of switching, whereby we question and change our assumptions about what we perceive, is of course an indispensable skill in perception of whatever kind, in whatever study. Here, before a wall of tiles in the Alhambra, we are given a chance to practice this art. So the tiles are a kind of athletic field of perception, where we might exercise in order to strengthen this very capacity of mind.

To return to the tiles: we next see that, beyond the enclosing octagon, the pattern flowers out along the interlocking white bands. It flowers both horizontally and toward the corners. This flowering occurs with various five- and six-pointed polygons, none of them regular pentagons or hexagons. Until suddenly, in the corners, we see the central pattern suddenly re-created (the golden octagonal star, unfolding into an octagonal figure, etc.). Surrounding the golden octagonal stars and figures in each corner, we see the same set of blue octagonal stars, and the same outline in white lines of the perfect enclosing octagon. One key pattern, then, is in the center and in all four corners. And there is a stunning sensation of movement, since the central pattern, as re-created in the corners, is incomplete. It is as if the whole design were alive and expanding before our eyes, moving beyond the borders of the design.

Here again is the role of this tile work as conductor of the mind: we see that the movement of the design is based on a harmonious and natural change of one form into another. Now, all of us change in the course of life, and the tiles speak to the notion that we might transform ourselves according to a radiant pattern alive within the world, and within us. Rather than change being chaotic and unwelcome, the tiles would suggest that there exists a natural path of change that might be traditional and available, by which we might proceed with clarity, precision, and integrity.

To put it another way: it is as if we are to learn that a clear and beautiful pattern in our own lives, once understood, can then, as our perception is extended, be found clear and resurgent in the world. It is a portrait of the way our lives might be part of an enveloping life, the way the world might offer a common and beautiful unity. Our minds, as we study these tiles, develop because we are being continuously sensitized to patterns of clairvoyant power. All of us live by patterns, in the way we think and the way we work. To see a pattern in each of our lives is to understand our place in that pattern, and, by extension, to know what to expect in the world from a given configuration of events.

To return once more to the tiles: if we look to each side of the central figure, we see the two strange forms: four octagonal stars (two green and two black) that look as if they are emerging from a white-bordered blue octagonal star; and at the corners of the figure, four green polygons with five vertices each. Once again the impression is that of inevitable emergence, of movement, of a harmonious channeling of energies.

And in the overall design, we can try to follow any one line, and track its various uses as it moves through the overall design. It is like driving a race car, since any one line swerves and veers, banks and curves, reverses course and rockets off in a new direction. It’s exhilarating; it’s just like walking in the Albayzín, and I have been tempted to post a satellite shot of the barrio on my wall, just to see if any of the patterns in the tiles are found in the network of streets that define our barrio. In following the lines in this wall of tile before us, we stop and note the forms they define: here a star, there an octagon, further on an emblematic figure of a man or woman standing, arms outstretched, in exaltation. In all this tracking, what is obvious becomes actively part of our experience, for there is no isolated line, there is no end point to the movement of the pattern; any one line can play its part in a whole variety of forms. We see before us what we say we have known all along: the necessary, organic connection of all things. It is driven home not in the pale form of a mere idea, but as a richly sensual experience of meditation as we look into the tiles. It is the idea made real, lovely, and irresistible.

Let’s return, after this journey around one wall of tiles, to the numbers that govern this design. First, it is dominated by eight, the number that is a portrait of earth as both material and transcendent, as matter in movement, yet turning in concord with a harmonious and perfect order. Transcendence, in some way, has to begin with the effort to bring a stable, harmonious order to the mind, to create a center point of peace that can sustain us and safeguard us as we live through the storm of events that comprise our days. The numerical theme here is a dense concentration of eightfold symmetries—a variety of stars and octagons, into which are woven the eight human figures. This very pattern, resurgent in the corners of the wall, suggests again how an order we find within may then be found in life itself. In other words, it is suggested that we can earn a capacity of mind that permits us to find within the world a more durable, transcendent order. Surely these tiles are meant to portray just such a deepening of experience, at core an experience of a merciful order in the mind that is at the same time a living order in the world.

The figures at the sides of the wall hold the numbers four, five, six, and eight: an internal blue octagonal star, surrounded by four emergent stars, making five centers altogether (the central star and the four emergent stars). The number five, we recall, refers to our senses and their progressive development as we try to refine our capacities of mind and perception. And it refers, as well, to the organic growth in the natural world. So once again, we have a geometric figure that portrays what can be our unity with the green and growing world, as we learn to join our life to all life.

If we stand back and review our meditation upon the patterns of just this one wall of tiles, what might we carry away with us? To understand the design, we must use care and patience, change perspective by switching figure and ground, learn how to see emergent patterns, focus on how one pattern fits with another, and comprehend how the whole is connected. And all of this, bound up with whole numbers which have the most resonant, productive associations with spiritual history, with the workings of the earth, and the order of our minds. What if these tiles are meant to teach? What if here, before us, is art that has the power to help us test our perceptions, to learn to sense patterns in the world itself, to be able to follow the harmonious unfolding of events, to recognize how one form of understanding leads to another, to sense our connection to the whole? What I claim here is that the tiles of the Alhambra are not just beautiful. They have a useful beauty. They are a gift offered to us so that we may learn by means of the dynamic exercise they give our perceptions. We are given a chance to form capacities of mind that make a harmonious and sentient change in the way we live. That is, we begin to see how patterns in life can show the workings of a more fundamental, inclusive order, an order in the world and within us. To begin to see ourselves as part of a comprehensive order connected with beauty is to have, beyond faith, a hope of integrity brought to us by a design both generous and sacred. We are in the presence of an art of stars. Whatever the delight they give with their beauty, whatever the admiration they excite with their play of arabesque, they speak to us of knowledge we need to thrive.

I offer these ideas in the full awareness that some readers will think I have gone round the bend, and that such reasoning provides not an effective suggestion so much as a heady dose of flimflam and blarney. I can only recommend to any such reader an extended stay with these walls of tiles, so that you may see for yourself what they offer you.

Either these tiles are a sacred art with a mathematical and cosmological basis, or they are merely décor. Either they are a beautiful proposition of number and pattern, an instructive offering to the mind, a music of numbers, a hopeful declaration about life and spirituality in the culture where they were created—or they are just another exercise in ornament. I have tried, over many visits, to see why they have exercised so powerful a hold on the imagination of so many over the centuries. And why they are so sophisticated: for example, modern mathematicians who work in an exotic field called plane crystallographic group theory have noted seventeen possible two-dimensional symmetry groups. Every single one of them are found in one or another place in the Alhambra. Workers in another rarified field in mathematics, called quasi-crystalline designs, have identified a certain pattern called a Penrose diagram, named after a cosmologist from Oxford. These same designs show up in Islamic tile work as far back as the thirteenth century.

We watch them with exaltation. Here, before us, is a work of understanding, designed with genius, that asks only our attention and study. Different walls of tile have distinct patterns, all with their own detail and import. In some designs in other rooms of the Alhambra, we see the same figures are produced in different forms and at a different scale. This is a principle known to us in the modern discovery of fractals, which are patterns in nature produced at dramatically different scales, which we see everywhere, from clouds to coastlines. It is another instance of the uncanny way these designs anticipate modern discoveries.

Experience must confirm and enliven what is mere concept. To offer such experience is part of the essential value of the Alhambra tiles. If there is a common theme in studies of the mind, it is that we fail to see what is most obvious. We see what we assume and cannot see what is right in front of us. As Jesus put it in the Nag Hammadi Gospels, in this exchange:

And the disciples asked: When will the Kingdom of Heaven come?

And Jesus said: The Kingdom . . . is spread out upon the earth, but men do not see it.

Standing before these walls of tiles, in visit after visit, we were seeking to answer the simplest of questions: Where, now, do we live? Our move to Granada had led us into the houses and gardens of our neighbors, who taught us how to live in the Albayzín. We studied the history of our garden, then of our barrio, then the glories and surprises of Al-Andalus. And this work led us across the Darro, to ascend to the Alhambra, and there to stand in the palace of the Nasrids and look at, and into, the trustworthy beauty of the ceramic tile work found everywhere in the castle.

Those lustrous designs became part of the design of our days; they made ideas material, made them into life. It is a most hopeful art, a portrayal of harmony deep in the world, of the meaning of numbers and the formation of order, of connection and clarity and the unity of faith and people. We think of it, even today, often, and always in praise of the anonymous and brilliant craftsmen whose light still shines in Granada and in the world.