The Cultures of Suffering

“What’s the point?” my father asked as he lay dying.

Training for Suffering

Suffering seems to destroy so many things that give life meaning that it may feel impossible to even go on. In the last weeks of his life, my father faced a great range of life-ending, painful illnesses all at once. He had congestive heart failure and three kinds of cancer, even as he was dealing with a gall bladder attack, emphysema, and acute sciatica. At one time he said to a friend, “What’s the point?” He was too sick to do the things that made his life meaningful—so why go on? At my father’s funeral, his friend related to us how he gently reminded my father of some basic themes in the Bible. If God had kept him in this world, then there were still some things for him to do for those around him. Jesus was patient under even greater suffering for us, so we can be patient under lesser suffering for him. And heaven will make amends for everything. These brief words, which were expressed in the most compassionate spirit, reconnected my father to Christian beliefs he had known for years. It restored his spirit to face his final days.

We will look at length at those Christian resources later, but at this point, it is necessary only to understand this: Nothing is more important than to learn how to maintain a life of purpose in the midst of painful adversity.

One of the main ways a culture serves its members is by helping them face terrible evil and adversity. Social theorist Max Scheler wrote: “An essential part of the teachings and directives of the great religious and philosophical thinkers the world over has been on the meaning of pain and suffering.” Scheler went on to argue that every society has chosen some version of these teachings so as to give its members “instructions . . . to encounter suffering correctly—to suffer properly (or to move suffering to another plane.)”12 Sociologists and anthropologists have analyzed and compared the various ways that cultures train its members for grief, pain, and loss. And when this comparison is done, it is often noted that our own contemporary secular, Western culture is one of the weakest and worst in history at doing so.

All human beings are driven by “an inner compulsion to understand the world as a meaningful cosmos and to take a position toward it.”13 And that goes for suffering, too. Anthropologist Richard Shweder writes: “Human beings apparently want to be edified by their miseries.”14 Sociologist Peter Berger writes, every culture has provided an “explanation of human events that bestows meaning upon the experiences of suffering and evil.”15 Notice Berger did not say people are taught that suffering itself is good or meaningful. (This has been attempted at various times, but observers have rightly called those approaches forms of philosophical masochism.) What Berger means rather is that it is important for people to see how the experience of suffering does not have to be a waste, and could be a meaningful though painful way to live life well.

Because of this deep human “inner compulsion,” every culture either must help its people face suffering or risk a loss of its credibility. When no explanation at all is given—when suffering is perceived as simply senseless, a complete waste, and inescapable—victims can develop a deep, undying anger and poisonous hate that was called ressentiment by Friedrich Nietzsche, Max Weber, and others.16 This ressentiment can lead to serious social instability. And so, to use sociological language, every society must provide a “discourse” through which its people can make sense of suffering. That discourse includes some understanding of the causes of pain as well as the proper responses to it. And with that discourse, a society equips its people for the battles of living in this world.

However, not every society does this equally well. Our own contemporary Western society gives its members no explanation for suffering and very little guidance as to how to deal with it. Just days after the Newtown school shootings in December 2012, Maureen Dowd entitled her December 25 New York Times column “Why, God?” and printed a Catholic priest’s response to the massacre.17

Almost immediately, there were hundreds of comments in response to the column’s counsel. Most disagreed with it but, tellingly, disagreed in wildly divergent ways. Some held instead to the idea of karma, that suffering in the present pays for sins in past lives. Others referred to the illusory nature of the material world, which comes from Buddhism. Still others accepted the traditional Christian view that heaven is a place of reunion with loved ones and will serve as consolation for suffering on earth. Some alluded to how suffering makes you stronger, implicitly drawing on the thought of Stoic and pagan thinkers from the classical Greek and Roman era. Others added that since this world is all we have, any recourse to “spiritual” consolation weakens the proper response to suffering—namely, action toward eradicating the factors that caused it. The only proper response to suffering, in this view, was to make the world a better place.

The responses to the column were evidence that our own culture gives people almost no tools for dealing with tragedy. Commenters had to look to many other cultures and religions—Hindu, Buddhist, Confucianist, classical Greek, and Christian—to address the darkness of the moment. People were left to fend for themselves.

The end result is that today we are more shocked and undone by suffering than were our ancestors. In medieval Europe approximately one of every five infants died before their first birthday, and only half of all children survived to the age of ten.18 The average family buried half of their children when they were still little, and the children died at home, not sheltered away from eyes and hearts. Life for our ancestors was filled with far more suffering than ours is. And yet we have innumerable diaries, journals, and historical documents that reveal how they took that hardship and grief in far better stride than do we. One scholar of ancient northern European history observed how unnerving it is for modern readers to see how much more unafraid people fifteen hundred years ago were in the face of loss, violence, suffering, and death.19 Another said that while we are taken aback by the cruelty we see in our ancestors, they would, if they could see us, be equally shocked by our “softness, worldliness, and timidity.”20

We are not just worse than past generations in this regard, but we are also weaker than are many people in other parts of the world today. Dr. Paul Brand, a pioneering orthopedic surgeon in the treatment of leprosy patients, spent the first part of his medical career in India and the last part of his career in the United States. He wrote: “In the United States . . . I encountered a society that seeks to avoid pain at all costs. Patients lived at a greater comfort level than any I had previously treated, but they seemed far less equipped to handle suffering and far more traumatized by it.”21 Why?

The short response is that other cultures have provided its members with various answers to the question “What is the purpose of human life?” Some cultures have said it is to live a good life and so eventually escape the cycle of karma and reincarnation and be liberated into eternal bliss. Some have said it is enlightenment—the recognition of the oneness of all things and the attainment of tranquility. Others have said it is to live a life of virtue, of nobility and honor. There are those who teach that the ultimate purpose in life is to go to heaven to be with your loved ones and with God forever. The crucial commonality is this: In every one of these worldviews, suffering can, despite its painfulness, be an important means of actually achieving your purpose in life. It can play a pivotal role in propelling you toward all the most important goals. One could say that in each of these other cultures’ grand narratives—what human life is all about—suffering can be an important chapter or part of that story.

But modern Western culture is different. In the secular view, this material world is all there is. And so the meaning of life is to have the freedom to choose the life that makes you most happy. However, in that view of things, suffering can have no meaningful part. It is a complete interruption of your life story—it cannot be a meaningful part of the story. In this approach to life, suffering should be avoided at almost any cost, or minimized to the greatest degree possible. This means that when facing unavoidable and irreducible suffering, secular people must smuggle in resources from other views of life, having recourse to ideas of karma, or Buddhism, or Greek Stoicism, or Christianity, even though their beliefs about the nature of the universe do not line up with those resources.

It is this weakness of modern secularism—in comparison to other religions and cultures—that we explore in these first few chapters.

Edified by Our Miseries

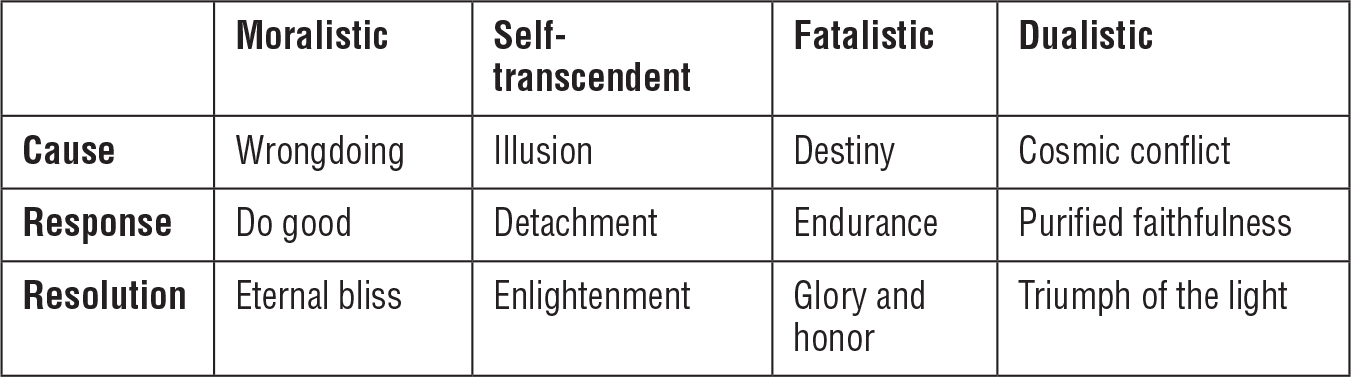

Richard Shweder provides a good survey about how non-Western cultures today help their people to be “edified by misery.” Traditional cultures perceive the causes of suffering in highly spiritual, communal, and moral terms. Here are four ways such societies have helped victims of suffering and evil respond.

There is what some anthropologists call (not pejoratively) the moralistic view. Some cultures have taught that pain and suffering stem from the failure of people to live rightly. There are many versions of this view. Many societies believe that if you honor the moral order and God or the gods, your life will go well. Bad circumstances are a “wake-up call” that you need to repent and change your ways. The doctrine of karma is perhaps the purest form of the moralistic view. It holds that every soul is reincarnated over and over. Into each life, the soul brings its past deeds and their latent effects, including suffering. If you are suffering now, it is likely your desserts from former lives. If you live now with decency, courage, and love—then your future lives will be better. In short, no one gets away with anything—everything must be paid for. Your soul is released into the divine bliss of eternity only when you have atoned for all your sins.

There is also what has been called the self-transcendent view.22 Buddhism teaches that suffering comes not from past deeds but from unfulfilled desires, and those desires are the result of the illusion that we are individual selves. Like the ancient Greek Stoics, Buddha taught that the solution to suffering is the extinguishing of desire through a change of consciousness. We must detach our hearts from transitory, material things and persons. Buddhism’s goal is “to achieve a calmness of the soul in which all desire, individuality, and suffering are dissolved.”23 Other cultures achieve this self-transcendence by being communal in a way almost impossible for contemporary Western people to comprehend. In such societies, there is no such thing as an identity or sense of well-being apart from the advancement and prosperity of one’s family and people. In this worldview, suffering is mitigated because it can’t harm the real “you.” You live on in your children, in your people.24

Some societies address suffering with a high view of fate and destiny. Life circumstances are seen as set by the stars or by supernatural forces, or by the doom of the gods, or, as in Islam, simply by the inscrutable will of Allah. In this view, people of wisdom and character reconcile their souls with this reality. The older pagan cultures of northern Europe believed that at the end of time, the gods and heroes would all be killed by the giants and monsters in the tragic battle of Ragnarok. In those societies, it was considered the highest virtue to stand one’s ground honorably in the face of hopeless odds. That was the most lasting glory possible, and through such behavior one lived on in song and legend. The greatest heroes of these cultures were strong and beautiful but sad, with high doom upon them. In Islam too, surrender to God’s mysterious will without question has been one of the central requirements of righteousness. In all these cultures, submission to a difficult divine fate without compromise or complaint was the highest virtue and therefore a way to find great meaning in suffering.25

Finally, there are those cultures with a “dualistic” view of the world. These religions and societies do not see the world under the full control of fate or God but rather as a battleground between the forces of darkness and light. Injustice, sin, and pain are present in the world because of evil, satanic powers. Sufferers are seen as casualties in this war. Max Weber describes it like this: “The world process although full of inevitable suffering is a continuous purification of the light from the contamination of darkness.” Weber adds that this conception “produces a very powerful . . . emotional dynamic.”26 Sufferers see themselves as victims in this battle with evil and are given hope because, they are told, good will eventually triumph. Some more explicit forms of dualism, like ancient Persian Zoroastrianism, believed a savior would come at the end of time to bring about a final renovation. Less explicit forms of dualism, such as some Marxist theories, also see a future time in which forces of good overcome evil.

At first glance, these four approaches seem to be at odds with one another. The self-transcendent cultures call sufferers to think differently, the moralistic cultures to live differently, the fatalistic cultures to embrace one’s destiny nobly, and the dualistic cultures to put one’s hope in the future. But they are also much alike. First, each one tells its members that suffering should not be a surprise—that it is a necessary part of the warp and woof of human existence. Second, sufferers are told that suffering can help them rise up and move toward the main purpose of life, whether it is spiritual growth, or the mastery of oneself, or the achievement of honor, or the promotion of the forces of good. And third, they are told that the key to rising and achieving in suffering is something they must take the responsibility to do. They must put themselves into a right relationship to spiritual reality.

So the communal culture tells sufferers to say, “I must die—but my children and children’s children will live on forever.”27 Buddhist cultures direct its members to say, “I must die—but death is an illusion—I will still be as much a part of the universe as I am now.” Karmic sufferers may say, “I must suffer and die—but if I do it well and nobly, I will have a better life in the future and can be freed from suffering someday altogether.” But in every case, suffering poses a responsibility and presents an opportunity. You must not waste your sorrows. All of these ancient and diverse approaches, though they take suffering very seriously, see it as a way toward some greater good. As Rosalind’s father, Duke Senior, says in Shakespeare’s As You Like It:

Sweet are the uses of adversity,

Which like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head. (Act 2, Scene 1, 12–17)

These traditional cultures see life as inevitably filled with suffering, and their prescriptions to their members have to do mainly with internal work. They call for varied forms of confession and purification, of spiritual growth and strengthening, of faithfulness to the truth, and of the establishment of right relationships to self, others, and the divine. Suffering is a challenge which, if met rightly, can bring great good, wisdom, glory, and even sweetness into one’s life now, and fit one well for eternal comfort hereafter. Sufferers are pointed to hope in a good future on earth, or eternal spiritual bliss and unity with the divine, or enlightenment and eternal peace, or the favor of God and unity with one’s loved ones in paradise.

Here’s a schematic of the various views:

Interrupted by Our Miseries

After surveying these other, more traditional cultures, Shweder points out that Western culture’s approach to suffering stands very much apart. Western science sees the universe as “naturalistic.” While other cultures see the world as consisting of both matter and spirit, Western thought understands it as consisting of material forces only, all of which operate devoid of anything that could be called “purpose.” It is not the result of sin, or any cosmic battle, or any high forces determining our destinies. Western societies, therefore, see suffering as simply an accident. “[In this view] while suffering is real it is outside the domain of good and evil.”28 An unusually clear statement of the secular view of evil and suffering is made by Richard Dawkins in his book River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life. He writes:

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. . . . In a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.29

This is a complete departure from every other cultural view of suffering. Each one sees evil as having some purpose as a punishment, or a test, or an opportunity. But in Dawkins’s view, the reason people struggle so mightily in the face of suffering is because they will not accept that it never has any purpose. It is senseless, neither bad nor good—because categories such as good and evil are meaningless in the universe we live in. “We humans have purpose on the brain,” he argues. “Show us almost any object or process, and it is hard for us to resist the ‘Why’ question. . . . It is an almost universal delusion. . . . The old temptation comes back with a vengeance when tragedy strikes . . . ‘Why oh why, did the cancer/earthquake/hurricane have to strike my child?’” But he argues that this agony happens because “we cannot admit that things might be neither good nor evil, neither cruel nor kind, but simply callous—indifferent to all suffering, lacking purpose. . . . As that unhappy poet A. E. Housman put it: ‘For Nature, heartless, witless Nature, will neither care nor know.’ DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we dance to its music.”30

In short, suffering does not mean anything at all. It is an evil hiccup. Dawkins insists that to deny that life is “empty, pointless, futile, a desert of meaninglessness and insignificance” is right, and to look to any spiritual resources to find purpose or meaning in the face of suffering is “infantile.”31

Shweder counters, however, that exhortations like Dawkins’s are both wrong and impossible to achieve. “The desire to make suffering intelligible,” he writes, “is one of those dignifying peculiarities of our species. . . .”32 That is, one of the things that distinguishes us from animals is that we do not simply squeal under suffering and seek to flee it. We search to find some point in the pain and thereby to transcend it, rather than seeing ourselves as helpless cogs in a cruel machine. And this drive to find meaning in suffering is not only dignifying, it is indelible. Peter Berger and the whole field of students of human culture insist that Dawkins is asking for the impossible. Without meaning, we die.

Of course, Dawkins goes on to say, “The truly adult view . . . is that our life is as meaningful, as full and wonderful as we choose to make it.”33 In other words, you must create your own meaning. You decide the kind of life that you find most valuable and worth living and then you must seek to create that kind of life.34

But any self-manufactured meaning must be found within the confines of this world and life. And that is where this view of reality and its understanding of suffering represent such a departure from all others. If you accept the strictly secular assumption that this is a solely materialistic universe, then that which gives your life purpose would have to be some material good or this-world condition—some kind of comfort, safety, and pleasure. But suffering inevitably blocks achievement of these kinds of life goods. Suffering either destroys them or puts them in deep jeopardy. As Dr. Paul Brand argues in the last chapter of his book The Gift of Pain, it is because the meaning of life in the United States is the pursuit of pleasure and personal freedom that suffering is so traumatic for Americans.

All other cultures make the highest purpose of life something besides individual happiness and comfort. It might be moral virtue, or enlightenment, or honor, or faithfulness to the truth. Life’s ultimate meaning might be being an honorable person, or being someone whom your children and community look up to, or about furthering a great cause or movement, or of seeking heaven or enlightenment. In all these cultural narratives, suffering is an important way to come to a good end to the story. All of these “life meanings” can be achieved not only in spite of suffering but through it. In all these worldviews, then, suffering and evil do not have to triumph. If patiently, wisely, and heroically faced, suffering can actually accelerate the journey to our desired destination. It can be an important chapter in our life story and crucial stage in achieving what we most want in life. But in the strictly secular view, suffering cannot be a good chapter in your life story—only an interruption of it. It can’t take you home; it can only keep you from the things you most want in life. In short, in the secular view, suffering always wins.

Shweder puts it this way. When it comes to suffering, the “reigning metaphor of this contemporary secular [view] is chance misfortune. The sufferer is a victim, under attack from natural forces devoid of intentionality.” And that means that “suffering is . . . separated from the narrative structure of human life. . . . a kind of ‘noise,’ an accidental interference into the life drama of the sufferer. . . . Suffering has no intelligible relation to any plot, except as a chaotic interruption.”35 In older cultures (and non-Western cultures today) suffering has been seen as an expected part of a coherent life story, a crucial way to live life well and to grow as a person and a soul. But the meaning of life in our Western society is individual freedom. There is no higher good than the right and freedom to decide for yourself what you think is good. Cultural institutions are supposed to be neutral and “value free”—not telling people what to live for, but only ensuring the freedom of every person to live as he or she finds most satisfying and fulfilling. But if the meaning of life is individual freedom and happiness, then suffering is of no possible “use.” In this worldview, the only thing to do with suffering is to avoid it at all costs, or, if it is unavoidable, manage and minimize the emotions of pain and discomfort as much as possible.

Victims of Our Miseries

One of the implications of this view is that the responsibility for responding to suffering is taken away from the sufferer. Shweder says that under the metaphor of accident or chance, “suffering is to be treated by the intervention of . . . agents who possess expert skills of some kind, relevant to treating the problem.”36 Traditional cultures believe that the main responsibility in dark times belongs to the sufferers themselves. The things that need to be done are forms of internal “soul work”—learning patience, wisdom, and faithfulness. Contemporary culture, however, does not see suffering as an opportunity or test—and certainly never as a punishment. Because sufferers are victims of the impersonal universe, sufferers are referred to experts—whether medical, psychological, social, or civil—whose job is the alleviation of the pain by the removal of as many stressors as possible.

But this move—making suffering the domain of experts—has led to great confusion in our society, because different guilds of experts differ markedly on what they think sufferers should do. As both a trained psychotherapist and an anthropologist, James Davies is in a good position to see this. He writes, “During the twentieth century most people living in contemporary society have become increasingly confused about why they suffer emotionally.” He then lists “biomedical psychiatry, academic psychiatry, genetics, modern economics” and says, “As each tradition was based on its own distinctive assumptions and pursued its own goals via its own methods, each largely favored reducing human suffering to one predominant cause (e.g., biology, faulty cognition, unsatisfied self-interest).”37 As the saying goes, if you are an expert in hammers, every problem looks like a nail. This has led to understandable perplexity. The secular model puts sufferers in the hands of experts, but the specialization and reductionism of the different kinds of experts leaves people bewildered.

Davies’s findings support Shweder’s analysis. He explains how the secular model encourages psychotherapists to “decontextualize” suffering, not seeing it, as older cultures have, as an integral part of a person’s life story. Davies refers to a BBC interview with Dr. Robert Spitzer in 2007. Spitzer is a psychiatrist who headed the taskforce that in 1980 wrote the DSM-III (third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) of the American Psychiatric Association. The DSM-III sought to develop more uniformity of psychiatric diagnoses. When interviewed twenty-five years later by the BBC, Spitzer admitted that, in hindsight, he believed they had wrongly labeled many normal human experiences of grief, sorrow, and anxiety as mental disorders. When the interviewer asked: “So you have effectively medicalized much ordinary human sadness?” Spitzer responded, “I think we have to some extent. . . . How serious a problem it is, is not known . . . twenty percent, thirty percent . . . but that is a considerable amount.”38

Davies goes on to say that the DSM focused almost completely on the symptoms:

They were not interested in understanding the patient’s life, or why they were suffering from these symptoms. If the patient was very sad, anxious, or unhappy, then it was simply assumed that he or she was suffering from a disorder that needed to be cured, rather than from a natural and normal human reaction to certain life conditions that needed to be changed.39

The older view of suffering was that the pain is a symptom of a conflict between a person’s internal and external world. It meant the sufferer’s behavior and thinking may need to be changed, or some significant circumstance in the environment had to be changed, or both. The focus was not on the painful and uncomfortable feeling—it was on what the feelings told you about your life, and what should be done about it. Of course, to make such an analysis takes moral and spiritual standards. It requires value judgments. And this was a discussion that the experts trained in secular cultural institutions are ill-equipped to facilitate. So the emphasis was instead not on the person’s life story but on the symptom of emotional pain and discontent. Through various scientific techniques, the job of the experts was to lessen the pain. The life story was not addressed.

Davies concludes:

The growing influence of the DSM was one among many other social factors spreading the harmful cultural belief that much of our everyday suffering is a damaging encumbrance best swiftly removed—a belief increasingly trapping us within a worldview that regards all suffering as a purely negative force in our lives.40

In the secular view, suffering is never seen as a meaningful part of life but only as an interruption. With that understanding, there are only two things to do when pain and suffering occur. The first is to manage and lessen the pain. And so over the past two generations, most professional services and resources offered to sufferers have moved from talking about affliction to discussing stress. They no longer give people ways to endure adversity with patience but instead use a vocabulary drawn from business, psychology, and medicine to enable them to manage, reduce, and cope with stress, strain, or trauma. Sufferers are counseled to avoid negative thoughts and to buffer themselves with time off, exercise, and supportive relationships. All the focus is on controlling your responses.

The second way to handle suffering in this framework is to look for the cause of the pain and eliminate it. Other cultures see suffering as an inevitable part of the fabric of life because of unseen forces, such as the illusory nature of life or the conflict between good and evil. But our modern culture does not believe in unseen spiritual forces. Suffering always has a material cause and therefore it can in theory be “fixed.” Suffering is often caused by unjust economic and social conditions, bad public policies, broken family patterns, or simply villainous evil parties. The proper response to this is outrage, confrontation of the offending parties, and action to change the conditions. (This is not uncalled for, by the way. The Bible has a good deal to say about rendering justice to the oppressed.)

Older cultures sought ways to be edified by their sufferings by looking inside, but Western people are often simply outraged by their suffering—and they seek to change things outside so that the suffering never happens again. No one has put the difference between traditional and modern culture more succinctly than C. S. Lewis, who wrote: “For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For . . . [modernity] the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique. . . .”41 Philosopher Charles Taylor, in his magisterial book A Secular Age, recounts how Western society made what he calls “the anthropocentric turn,” the rise in the secular view. After this turn, Taylor says the “sense of God’s ordering presence begins to fade. The sense begins to arise that we can sustain the order [of the world] on our own.” As a result, Western society’s “highest goal is to . . . prevent suffering.”42

In Western culture, then, sufferers are not told that their primary work is any internal adjustment, learning, or growth. As Shweder points out, not only is moral responsibility virtually never assigned to sufferers but to even hint at it is considered “blaming the victim,” one of the main heresies within our Western society. The responses to suffering, then, are always provided by experts, whether pain management, psychological or medical treatment, or changes in law or public policy.

In the Boston Review, Larissa MacFarquhar was interviewed on her writing and research on very “saintly” people who make great sacrifices for the good of others. Many of them were religious, of course, and MacFarquhar, a staff writer for The New Yorker, had no religious faith, nor was she raised in one. At one point, the interviewer asked how she viewed these people. She spoke with insight and candor, speaking about “a difference between religious . . . and secular people that was very enlightening.” She said:

I . . . think that, within many religious traditions, there is much more of an acceptance of suffering as a part of life and not necessarily always a terrible thing, because it can help you become a fuller person. Whereas, at least in my limited experience, secular utilitarians hate suffering. They see nothing good in it, they want to eliminate it, and they see themselves as responsible for doing so.

She said that secular people also have no belief in a God who will someday put things right. For people of faith, “God is in control, and God’s love will see the world through. Whereas for secular people, it’s all up to us. We’re alone here. That’s why I think that, for secular people, there can be an additional layer of urgency and despair.”43

Christianity among the Cultures

Here, then, is a schematic way to understand secularism as a fifth culture of suffering:

How does Christianity compare to all of these? German philosopher Max Scheler, in his famous article “The Meaning of Suffering,” pointed out the uniqueness of the Christian approach. Scheler writes that in some ways, “Christian teaching on suffering seems a complete reversal of attitude” when compared to the interpretations of other cultures and religious systems.44

Unlike the more fatalistic view so prevalent in the shame and honor cultures, “in Christianity there is none of the ancient arrogance . . . none of the self-praise of the sufferer who measures the degree of his suffering against his own power to which others bear witness.” Instead of stoic endurance of high doom, “the cry of the suffering creature resounds everywhere in Christianity freely and harshly,” including from the cross itself.45 Christians are permitted—even encouraged—to express their grief with cries and questions.

Unlike Buddhists, Christians believe that suffering is real, not an illusion. “There are not reinterpretations: pain is pain, it is misery; pleasure is pleasure, positive bliss, not mere ‘tranquility’ . . . which Buddha considered the good of goods. In Christianity there is no diminution of sensitivity, but a mellowing of the soul in totally enduring suffering.”46 Again, we see this in Jesus himself. In the Garden of Gethsemane, he said, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow even to the point of death” (Mark 14:34) and his anguish was such that his bloody sweat fell to the ground as he prayed (Luke 22:44). He was the opposite of tranquility. He did not detach his heart from the good things of life to achieve inner calm but instead said to his Father, “Not my will but thine be done” (Mark 14:36).

Unlike believers in karma, Christians believe that suffering is often unjust and disproportionate. Life is simply not fair. People who live well often do not do well. Scheler writes that Christianity succeeded in doing justice to the full gravity and misery of suffering by acknowledging this, as the doctrine of karma does not, which insists that all an individual’s suffering is fully deserved. The book of Job is of course the first place this is clearly stated, when God condemns Job’s friends for their insistence that Job’s pain and suffering had to be caused by a life of moral inferiority.

We see this most of all in Jesus. If anyone ever deserved a good life on the basis of character and behavior, Jesus did, but he did not get it. As Scheler writes, the entire Christian faith is centered on “the paragon of the innocent man who freely receives suffering for others’ debts. . . . Suffering . . . acquires, through the divine quality of the suffering person, a wonderful, new nobility.” In the light of the cross, suffering becomes “purification, not punishment.”47

Unlike the dualistic (and to some degree, the moralistic) view, Christianity does not see suffering as a means of working off your sinful debts by virtue of the quality of your endurance of pain. Christianity does not teach “that an ascetic, voluntary self-affliction . . . makes one more spiritual and brings one closer to God. . . . The interpretation that suffering in itself brings men nearer to God is far more Greek and Neoplatonic than Christian.”48 Also, dualism divides the world into the good people and the evil people, with suffering as a badge of virtue and the mark of moral superiority that warrants the demonization of groups that have mistreated you. In stark contrast, Christians believe, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote famously, “The line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”49

No, the Christian understanding of suffering is dominated by the idea of grace. In Christ we have received forgiveness, love, and adoption into the family of God. These goods are undeserved, and that frees us from the temptation to feel proud of our suffering. But also it is the present enjoyment of those inestimable goods that makes suffering bearable. Scheler writes: “It is not the glowing prospect of a happy afterlife, but the experienced happiness of being in a state of grace of God while in throes of agony that released the wonderful powers in the martyrs.” Indeed, suffering not only is made bearable by these joys, but suffering can even enhance these joys, in the midst of sorrow. “The Christian doctrine of suffering asks for more than a patient tolerance of suffering. . . . The pain and suffering of life fix our spiritual vision on the central, spiritual goods of . . . the redemption of Christ.”50

Finally, how does the Christian prescription for sufferers compare to that of the secular culture? We will devote more time to this important question later, but we can summarize it like this. Christianity teaches that, contra fatalism, suffering is overwhelming; contra Buddhism, suffering is real; contra karma, suffering is often unfair; but contra secularism, suffering is meaningful. There is a purpose to it, and if faced rightly, it can drive us like a nail deep into the love of God and into more stability and spiritual power than you can imagine. Suffering—Buddhism says accept it, karma says pay it, fatalism says heroically endure it, secularism says avoid or fix it. From the Christian perspective, all of these cultures of suffering have an element of truth. Sufferers do indeed need to stop loving material goods too much. And yes, the Bible says that, in general, the suffering filling the world is the result of the human race turning from God. And we do indeed need to endure suffering and not let it overthrow us. Secularism is also right to warn us about being too accepting of conditions and factors that harm people and should be changed. Pre-secular cultures often permitted too much passivity in the face of changeable circumstances and injustices.

But, as we have seen, from the Christian view of things, all of these approaches are too simple and reductionist and therefore are half-truths. The example and redemptive work of Jesus Christ incorporates all these insights into a coherent whole and yet transcends them. Scheler ends his great essay by returning to his claim that Christianity is ultimately a reversal of all the other views.

For the man of antiquity . . . the external world was happy and joyous, but the world’s core was deeply sad and dark. Behind the cheerful surface of the world of so-called merry antiquity there loomed “chance” and “fate.” For the Christian, the external world is dark and full of suffering, but its core is nothing other than pure bliss and delight.51

He is right about most of the ancient cultures, but what he says especially fits the secular worldview. Secularism, as Richard Dawkins says, sees ultimate reality as cold and indifferent and extinction as inevitable. The other cultures also have seen day-to-day life as being filled with pleasures, but behind it all is darkness or illusion. Christianity sees things differently. While other worldviews lead us to sit in the midst of life’s joys, foreseeing the coming sorrows, Christianity empowers its people to sit in the midst of this world’s sorrows, tasting the coming joy.

Life Story: The Fairy-Tale Ending

by Emily

If you had asked me what I was thankful for before September, I would have said that I am thankful for my family, my home, my job, and for God—for a husband who loves and cares for me, for four children (ages fourteen, eleven, nine, five) who are healthy and happy, for a home I never dreamed I could have, for a career that allows me to work from home, use my brain, and make a difference for my company and my clients, and for a God that has provided me those things—regardless of my worthiness.

In September, completely out of the blue, my husband left me and our four children for someone else (who left her husband and two children as well). This other family were friends of ours; we’d vacationed with them on three separate occasions during the summer. I thought they were our friends.

My heart died within me. This could not be happening. My Christian husband—the one who with me sat down with our kids and explained that while divorce does happen, it would never happen to us—we made a covenant, a promise to God and to each other—no matter what—we will always be here for each other and for them. I sobbed and begged him not to go, that we would figure this out. No, he was leaving.

I asked what he was going to tell the kids; he said he didn’t know. I told him, “You can’t just leave without telling the kids something.” Surely, this would hit him—he would not be able to look at these precious children and tell them that he was leaving . . . but he did. He called them back downstairs from bed and told them he was leaving. They didn’t understand. . . . Is this for work? When will he be back? No, kids, I’m moving out—not to come back. He left. We were crushed.

After eight weeks, my heart was still crushed. God, is this really your plan? How could this be your plan? I know that you will heal my heart, I know that something good will come from this—but how and why THIS? I feel you—I feel people praying . . . but what is going to become of us? I have never been so angry. Our poor children are suffering terribly; their father’s “wants” come before their “needs.” “I still love my kids,” he says. Really? How can you love them and cause them such pain?

After four months, God is beginning to heal me in a way I’m not sure I want to be healed. I want to see justice, but it is not mine to inflict. I am beginning to try to pray for him . . . not about him. I am beginning to pray for his heart to be healed. For him to come back, not to me but back to God. I need to move on without him, for now and maybe forever, but I have to forgive him to get through the bitterness. I will not be bitter for the rest of my life.

But how am I going to make it? God says pray, so I do.

I love my family, and I will always love the man I married. I’m praying for a miracle—for him to snap out of this and find his way back home—but I am also moving forward without him. I’m planning and trying to continue with my life, with everything that needs to be done from a practical, spiritual, emotional, and financial perspective.

I am going to pray for him on a regular basis, I am going to love him (but I will not be a doormat). I am going to support my family and I am going to seek God’s plan for our life. I am going to forgive him, but I won’t forget—because if I forget, I won’t be able to use what I learn to help others who may go through this nightmare. I need to feel the pain, allow God to heal that pain and transform me into someone that he had intended for me to become all along. Somehow, I feel excited. It feels wrong in so many ways—to be excited to be going through this nightmare.

It has now been six months, my situation has gotten worse, and yet I feel truly blessed.

My husband is still gone, still with his girlfriend. He has told me that they will be a part of our kids’ lives and I need to get used to that and not hate her. He told me that if she was my enemy, then I was his.

My kids are still dealing with the impact that their dad left; they are depressed, angry, confused, and frustrated. My oldest has started questioning his faith; he is rebelling against all authority, and lashing out at his family. My house is up for sale—a short sale, which could turn into being a foreclosure. We have no idea where we will move.

And yet, in the midst of all this—I have come to know God on a different level, to see him work in a way I had only heard about. To experience this is quite amazing.

I’ve never had a big tragedy in my life—never really had to depend on God. I mean, sure, I prayed and I saw God work—but not like this. I never had the need to rely on God, truly just fall and rest on him. When I needed God’s comfort, the image in my head was me clinging to Jesus and him hugging me. My image now is me just completely collapsed, and him carrying me—and it is awesome.

In the midst of this horrible situation, where my whole identity and where my family has been attacked, I see glimpses of what God is doing and how my life and our lives will be changed—and I get excited to see who I get to be at the end of all this. Like being in a race, where it starts to rain and you hit a mud pit. You can’t go around it, you have to go through it—and the rain and the mud are weighing you down—you can’t go through it fast; you must concentrate on each painful step . . . but at the same time, something is keeping you upright and compelling you to continue. In the distance, you see what appears to be a sheet of rain (almost like a car wash rinse) and then you see it—the sun; it is perfectly clear . . . The person you will be there will be stronger, with more understanding of how to run this race, and with satisfaction/peace. Yes, that person is tired—but they are also energized by the experience. I can’t wait to use what God has taught me; I can’t wait to learn more. I have explained it to my children like this: In every fairy tale, there is always a tragedy, and the protagonist faces that adversity, overcomes it, and thrives because of it. God is giving us our fairy tale—what do you see at the end?