When it comes to evaluating your running there is no more profound question than this. You probably run the same way you did as a child, perhaps with the intervention (as I had) of some questionable coaching advice about heel-toe running. Depending on your age, you may have been running with the same technique for many years. This movement pattern is deeply engrained in your brain, neuromuscular pathways and muscles that have been conditioned and de-conditioned accordingly. Any changes you make are going to be challenging and, as I have found, require some effort. But the good news is change and improvements are possible.

What you need to know is: should you change or improve your running technique? Does it need revolution or evolution? The second question is important; perhaps what you’ve got is not too bad and just needs a tune up. It may be that, with the addition of basic strength and coordination exercises, structured training and awareness of proper technique that your running will evolve naturally. On the other hand, you might be getting the sense that there are serious problems with the way you run. This chapter will give you some clues on whether your technique is broken or only needs minor repair.

The objective of this chapter is to help you to

identify whether you or an athlete that you coach should consider

making changes or improvements to your/their technique. Like any

important decision it helps to have criteria on which to make an

assessment about whether making a technical change is warranted and

worthwhile. Ultimately, you or your athlete will need to undertake

running technique/gait analysis to inform the decision and identify

any specific issues that may need to be remedied. This chapter

considers all aspects of whether you will truly benefit from and be

motivated enough to improve your running technique by:

- explaining that shoes and equipment alone won’t improve your

running;

- understanding the personal triggers that might prompt or motivate

a technique change;

- analyzing your technique and understanding which muscle groups

are driving your running;

- identifying any common flaws you share with other runners;

- thinking about if there is a pattern of injury and pain connected

to your running technique;

- determining what this injury or soreness pattern can tell you

about your technique;

- documenting any preconceptions you have about your

technique;

- having an accurate a mental picture of how you are running;

and

- answering the question: should I change or improve my

technique?

The quick fix: new shoes or no shoes will correct my technique. With the amount of interventionist running technology (mostly shoes) it would be easy to think if I just wear shoe A or compression tight B, I’ll become a better runner with improved technique or at least be able to manage my soreness and prevent injury. You might believe this technology will somehow compensate for what you deep down know are some serious flaws in the way you run. This is a seductive thought and one that I’ve fallen for numerous times over the years; my collection of unloved and mostly unworn shoe technologies is a testament to this. Improving your technique is a much deeper process than just slipping on or off a pair of shoes.

There are risks in change, but the rewards are great. I’m sorry to be blunt about it, but if you are in the broken technique category (that was me) it’s going to be a challenging process to improve your technique. But on the plus side, if you’re technique is broken, it can also be fixed with a little knowledge and hard work. The pleasure you’ll get from demolishing old records, moving more fluidly and reducing injuries makes all the hard work worthwhile. Changing your technique is a risk, you might get sore, you might even pick up a new niggle or injury along the way. You need to be honest, if your running career is already confined to a physical therapist’s table maybe it’s a risk worth taking?

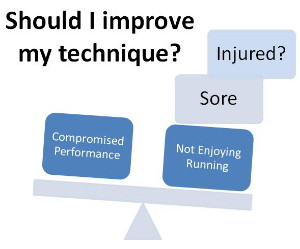

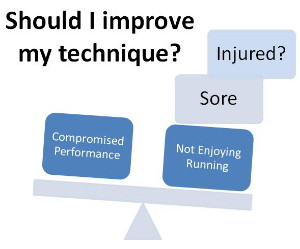

It comes down to three personal triggers and motivators for change: injury, performance and enjoyment. As a driven person, improvements in performance and reduction or treatment of injuries were my main motivators. However, since making changes for the better, I now find that my enjoyment of running has increased dramatically. This has helped me to get some perspective, slow down, not train as obsessively and just enjoy the flow of running well. I’m now completely committed to not getting re-injured by overtraining. Most of my running now feels great (not just post work-out highs) and this would be taken away from me if I got injured again. So in summary if you have two out of the three following factors motivating you, it might be worth changing or improving your technique.

Enjoyment. Many runners compete in the sport and love training hard for the incredible enjoyment it brings. Training and racing deliver tremendous runner’s highs and just getting outside in the fresh air at your local park or into the bush and trails is enough to motivate people to run. The problem for many runners is it hurts, pure and simple, it feels jarring, your bones rattle and your muscles ache after even a small amount of running. There’s no spring in your stride, everything feels heavy and it’s plain hard work. It is a testament to the character and motivation of runners like this who still get out there to run socially and competitively on a regular basis. This was completely my profile, I loved running; pushing myself, enjoying the outdoors and settling down after a run filled buzzing with endorphins that could float you off your feet. But it always hurt and I thought this was normal, maybe all runners go through this? Well, I think every runner, even Olympians, have pain at some level, but theirs is from training at the boundaries of performance and injury: I’d be sore after jogging 30 kilometers (20 miles) a week. If someone had come to me and said, “Brian, your running technique is the problem and I can show you how to fix it,” I probably would have paid them anything to learn more. Luckily you don’t need a million dollar treadmill, expensive video and computer software to show you the basics of how to run properly. If you love running but can’t enjoy it because of the pain, keep reading to find out how this can be fixed.

Injury. If you have an injury that just won’t heal, no matter how many thousands you spend on physical therapy, special shoes, orthotics and compression wear, then chances are it is being caused by a problem with your running technique and/or weakness in key running muscles. No amount of treatment or money will fix this kind of injury, you either need to change the way you run or stop running: I know which choice I made. A painful injury caused me to choose between not running or trying to decipher what in my running technique was causing the injury. After a lot of thinking and analyzing video of my running I worked out that the problem was caused by over-extending my knees with every stride. After a few weeks jogging with baby step changes towards a better technique, the pain started to go away.

I would always look hard at technique when diagnosing an injury. Shoes, surfaces, training load can all play their part in causing an injury, but the way you run is surely the most profound influence on whether you get hurt from running. If you are injured and can’t find the answer in the usual places then it’s worth taking the time to examine and improve your running technique. One of my primary motivators is to make running more accessible and enjoyable. To attract and retain runners in the sport, people need enough basic information to help them move in a way that reduces the risk of injury.

Performance. If you run in organized running races at any level, chances are you are a competitive spirit, most runners I know are. It does not matter if you can run 10 kilometers in 30 minutes or 60 minutes, all runners take pride in their performance, and a personal best/record is something to be celebrated no matter what level you run at. With so much focus and adulation on elite runners, national and state associations, coaches and club administrators can forget that slower runners care about their performance just as much as someone striving to make the national team. Without the masses there is no sport, no endorsements for elite runners and fewer junior athletes entering the sport who might have the talent to one day make the national team.

The historical attitude in relation to running technique is that people run with a technique that is self selected and most appropriate/efficient for them. The problem with this approach is it leaves slower runners who suffer pain and injury to suffer with their lot. Bad luck, you’re just an average, injury prone runner, there’s nothing that can be done about it. I don’t believe this for a second - everyone can improve.

There is no doubt that technical improvements for slower runners are possible and the best bit is the results and records that will follow are much bigger and easier to obtain than running personal bests/records for a guy who can already run a 15 minute 5000m or a girl who can run 17 minutes. It took me 13 weeks of training coming back from an injury caused by my old technique (6 weeks of jogging, 7 weeks that included harder sessions) to slice over a minute off my 5000m personal best/record. I did the same training volume, same types of workouts. As a final word on this, if you know you’re a good competitor and have better endurance and guts than your running times would indicate, then there’s a good chance you have room for improvement in your running technique. Slower runners can be very tough and often have great cardiovascular reserves: maybe technique is all that is holding you back?

Is your motivation strong enough? I believe if you have two out of the three factors discussed above then you have motivation enough to take on the challenge of improving your running technique. If your technique is sound, then I’d still recommend getting a gait analysis done, especially if you’re considering a big increase in training volume for an event like the marathon or half-marathon. If there are weaknesses in your running technique, big repetitive miles will expose them soon enough. It’s a good idea to iron these out before you start punching out 100+ kilometer (60 mile) weeks.

Three types of runners. In the course of thinking about writing this book I’ve tried to begin classifying the different kinds of running technique that I see in my coaching practice, day-in day-out at competitions or just jogging around Melbourne’s famous Tan Track that circumnavigates the Royal Botanic Gardens. I’ve arrived at three broad groupings - there are sub groups within these classifications as each runner has their own unique attributes, but for now they form a useful basis of discussion. I’ll discuss them here in order of bad to good.

Front drive crash-landers. This was me. A

running technique characterized by dominance of the quads and hip

flexors thrusting the legs forwards to create each stride. The

results being a technique that visually looks a bit like a race

walker with the runner crash landing from one leg to the next. This

technique is all about thrusting the legs ahead of the body rather

than the legs driving the body ahead of the hips. Some of the signs

of this technique are:

- Very low back-kick because the hamstrings are passengers and

barely used.

- Very low forward knee drive (as there is little knee flexion from

back-kick).

- Fully extended knees and landing with a straight leg well ahead

of the body.

- An exaggerated heel-toe action.

- Hitting the ground hard, everyone can hear you coming.

- Running on hard surfaces hurts too much and you hate running

downhill.

- Feet contacting the ground under the midline of the body, not

under the hip.

- You legs are close together - often clipping each other as you

run.

- Unstable hips, the hips drop from side to side.

- Slow stride rate <170 strides per minute.

- A technique that is stretched and almost always in contact with

the ground.

These types of runners may often have well developed quadriceps muscles that look quite impressive from the front, but don’t really deliver much in terms of performance. They’ll have a flat butt and very little muscle mass in the hamstrings.

Some of the injuries or pain you might be

feeling:

- Smashed quadriceps and sore knees.

- Iliotibial band syndrome (ITB) soreness.

- Sore shins or stress fractures.

- Calf strains and pain behind the knee from over-extending your

knees.

As you run faster you most likely feel as if your running mechanics are out of control, your legs are all over the place and it’s very hard to maintain any rhythm. You feel like you carry your legs rather than them carrying you. You often run up hills pretty well because your cardio fitness it good and hills bring the faster runners back to the field. You can’t run downhill though, this hurts too bad and all the runners you passed on the way up cruise past you on the way down. How annoying is that!

If this is you then your technique needs to be fixed. This is not a running style issue; this is a poor technique issue. You need to strengthen your body and reprogram your brain to think about running as a hamstring and glute powered movement pattern rather than a quad and hip flexor driven movement. I feel your pain, this was me, but there is hope: as Coach Mark Gorski once said to me, you’ve managed to crawl out of a very deep and dark hole!

Rear drive landers. This group is in the

category that I would argue requires evolution rather than

revolution and is probably the majority of runners. The primary

muscle activation pattern is good in that these runners do generate

thrust from the hamstrings and glutes. However, they may not

activating the hamstrings and glutes sufficiently ahead of landing

and during contact with the ground. The consequence being: the foot

and leg lands passively, lacking the engagement of the glutes,

hamstrings and calves to stabilise the hip, knee and ankle joints.

This technique is harder to spot with the naked eye as it looks

reasonable because the fundamentals are not too bad. Some of the

signs of this technique are:

- The athlete runs along a central line rather than with feet under

the hips.

- The thigh and leg may internally rotate during late forward

swing.

- May not maintain a good long upright spine posture.

- Lands without extreme heel strike, but likely to land towards the

heel.

- May over-extend their knees because of late engagement of the

hamstrings.

- Likely to have unstable hips, knees and ankles.

- May pop up and down as the hips collapse on landing then drive up

as the hamstrings and glutes engaged.

Injuries or pain you might be

feeling:

- Hip soreness and injury.

- Hamstring tendonitis, hamstring strains.

- Sore shins and stress fractures.

Sound runners. This final group are the lucky ones; they’re likely to be talented and able to run swift times without a good deal of training behind them. They are not invincible though and many have little chinks in their armour that can lead to injuries if they are training or racing intensely. However, this group of runners is only likely to need fine tuning to their technique rather than radical overhaul: lucky them!

Sound runners are naturally able to generate early activation of the glutes and hamstrings and run with a powerful and springy stride. This also means they are much more stable and resistant to injury. For a more detailed description of how these runners move, refer to chapter 4 and chapter 5. However, talented and elite runners can still have problems, if they are fortunate, they will have expert coaches, physiotherapists and other professionals on hand to help. Elite runners, especially those just below word-class can and do have issues with their running technique. Their issues are usually more minor than those that everyday runners face, but the volume of training and the increased forces involved in running fast for sustained periods can lead to injury.

Document your preconceptions about your running. There’s no doubt we all carry around assumptions and things we think we know about ourselves. In relation to running, this is an area we seriously need to understand and challenge before we can move forward with improving running technique. I carried a number of beliefs about my running with me for years. Some of these I came up with all on my own, others were implanted by people imparting well-meaning but flawed advice. The final piece of the puzzle I’d constructed was unhelpfully provided by running shoe salesmen in charge of too much gimmicky technology with too little knowledge.

Before you undertake gait analysis write down what you think you know about your running. I didn’t do this, but I can remember what I thought I knew and have documented this so you get the idea of what I’m talking about. You need to understand your blind spots to improve.

Brian’s assumptions and reality check. So I thought I knew a fair bit about my running and running in general. You can see I was a long way off base with many of my beliefs about running. Here’s my list of assumptions and the reality of my running after I analyzed my gait on video and did some more research.

Assumption and knowledge: I landed towards my forefoot. Reality: I was landing on my heel in extreme dorsiflexion (toes pointed up).

Assumption and knowledge: I was good at minimizing air time and landing shock and that this was a good thing to do. Reality: I was creeping across the ground compromising any potential to generate force by thinking about how I could land softly. I was almost always in contact with the ground with no float time and a relatively small distance being covered for each stride despite have a widely spread gait. My stride was weak and generated no rear thrust or power because hip extension happened as an afterthought in my technique not as a driver of it.

Assumption and knowledge: My running style was efficient. Reality: My running style was inefficient because the main drivers of good running - hamstrings and glutes were barely used.

Assumption and knowledge: I pronated and needed $300 motion controlled shoes. Reality: My foot motion is neutral and I now wear relatively minimal shoes.

Assumption and knowledge: I probably needed orthotics. Reality: I didn’t need orthotics, or the expensive cushioned inserts I had been using or the fluffy ultra cushioned socks.

Assumption and knowledge: It was a good idea to run along a central line. Reality: This was a bad idea and made me unstable at the hips.

Assumption and knowledge: Quadriceps are the most important muscles in running. Reality: The buttocks and hamstrings are the most important muscles in running.

When should you change your technique? Are you injured? If you’re injured and you’ve pinpointed a technique related cause to the injury then this is the perfect time to think about improving your technique. Even if you can’t run, you may be able to begin strength and coordination training that will make the transition much easier when you recommence running.

There’s also a slightly sadistic benefit to being injured and making a technical change: after the acute phase is over, you’re likely to be able to run again, but usually with some discomfort. If your injury was caused by technique, then every time you backslide or get lazy you will be reminded very quickly by your sore body that you need to work harder to get the technique right. I’m not saying this is enjoyable, but it does help you focus and when the pain finally goes away for good it is great confirmation that your technique is on the right track. Caution: Don’t try and run through pain that gets worse as you run - stop and rest for a few days and seek advice from a physical therapist if necessary. Make sure you follow the advice of your physical therapist and doctor. Depending on your injury e.g. stress fractures, then rest is the best remedy and any form of running with make things worse and delay your recovery. Give your body time to heal.

Not injured? In chapter 8 I discus a number factors that might influence when you decide to make a change in your running - in short, the off season is the best time, well away from your next competition and the pressures of your training group. If you’re on the cusp achieving your competitive goals and you’re running well without injury, don’t risk messing with your winning formula. Come back to it later.

So should I change or improve my technique? If you are thinking about changing or improving your technique you must get a proper gait analysis undertaken. If you have access to a video camera then you’ve got all the tools you need. A treadmill is also handy, but you don’t absolutely need it, although it does make things easier. In chapter 6 I’ll discuss how to do a gait analysis and what to look for when analyzing key aspects of your technique.

Remember even if you do the analysis yourself or with a friend it’s a good idea to shop around your video to take on board the advice of experienced runners, coaches and specialists. Ultimately, the decision to make changes or improvements in your technique is your decision or one that you make in conjunction with your coach. To me the three drivers I identified in this chapter, enjoyment, injury and performance should be at the forefront of your mind when making the decision.

If you don't have a history of major running injury problems or your running niggles are minor, then looking to do a major overhaul of your running technique is probably not the first step you should take. Even if you're searching for big improvements in your personal best times, the first thing you should consider doing is adding a well thought-out strength training program into your training mix. I provide much more detail on the type of strength training that you should consider later in the book, but you might be surprised how much improvement you can extract from your body by regular strength training with relatively simple body weight exercises. Strength training is running technique training by proxy and it's by far and away easier than consciously trying to make big changes to your running technique. A word of caution, doing the right kind of strength training with correct technique is essential. Training the wrong muscles or using incorrect muscle activation patterns is likely to do more harm than good - I have included much more information on this later in the book. Once you've had your running technique analyzed you'll have a better idea about which pathway to take.

In the next two chapters I'll explain more about what good running technique looks like and which muscles are involved in executing sound running technique. After you absorb this information and complete a gait analysis you’ll have all the information you need to weigh up the pros and cons of making any changes or improvements to your running technique.

****