We’ve all seen elite athletes running effortlessly around the track or over the roads and pavements in big city marathons and fun runs. I never tire of watching their smooth moves, the power, grace and romance of it appeal to me greatly and I’d go a long way to watch good runners ply their craft.

But understanding what this beautiful running is comprised of isn’t easy, because it’s difficult to see with the naked eye exactly what’s going on. The runners are moving incredibly fast and they’re taking at least three strides per second; even the men and women racing the marathon are travelling at impressive speeds. Observing an athlete moving at twenty kilometers per hour or more is a challenging thing to absorb in real time. You get the impression of fluid, metronomic movement, pawing of the ground, a bouncy stride and the rapid flutter of back-kicking legs. But all that leaves you with is an overriding sense of awe at how easy running looks for these talented individuals.

Here are the names of some contemporary elite runners that I’ve studied live* or on television that all exhibit the strength, elegance and excellent technique that I’m referring to:

Women: Kara Goucher, Eloise Wellings*, Catherine Ndereba, Sharlane Flanagan, Lynette Masai, Paula Radcliffe and Tirunesh Dibaba.

Men: Josphat Menjo*, Moses Kipsiro, Chris Solinsky*, Bernard Lagat*, Ryan Gregson*, Ben St Lawrence*, Nick Willis*, Mo Farah and David Rudisha*.

You could argue that each of these athletes looks slightly different in style, but the core technique and pattern of muscle activation is definitely the same. Do any of these athletes demonstrate perfect running technique? Most likely, among elite athletes these are stand-out performers. However, the common elements all good runners demonstrate, not arbitrary judgments about who looks the best interest me the most. This provides a valuable benchmark for regular runners to learn from and train for.

When you study slow motion footage, running begins to make sense. By this I mean slowing down video of these runners moving at race speeds, but also observing how they move at slower speeds so the analysis becomes relevant for recreational and club runners like you and I. This chapter is about identifying the heart of what good running technique looks like and explaining the observable benchmarks exhibited by good runners at different speeds.

Chapter outline. This chapter is designed

to give you a feel for the look of good running technique. You can

use this information to visually benchmark your technique (with the

aid of photographs and video footage) to monitor your progress in

making technical improvements. If you are a coach working with

athletes to target developing these external technical

characteristics, this will help you quickly evaluate how well your

runners are moving. This chapter describes the:

- running cycle or gait broken into four phases;

- visual signs of good technique at each stage of the four phase

cycle; and

- visual signs of technical flaws at each stage of the four phase

cycle.

A note about the discussion for regular runners. I have deliberately sought out studies to support my explanation that describe the technical characteristics of talented runners. I’m not trying to depress anyone by doing this; I look at and explain these studies with the goal of providing an objective benchmark for good running technique. Elite runners provide the best example of technical excellence. To keep things relevant for the regular running community the studies used as a source of discussion also show talented runners moving at slower as well as race speeds, 8 minute mile (5.00 minute km) and 6 minute mile (3.43 minute km). What I found interesting was that there was no change in the muscles used at different paces. The conclusion being, that the same basic muscle activation pattern for running well exists whether you are a 5 minute kilometer runner or a 3 minute kilometer runner. It then becomes a question of how strong, coordinated and finally fit you are to be able to sustain that pattern at faster speeds. This makes the discussion completely real for a 40-60 minute 10 kilometer runner. If an elite athlete can move at slower speeds using good technique, then so can you.

Four phases of running. I have read many descriptions for the phases involved in the running gait or cycle: floating, swinging, toeing off, thrusting, support, heeling off, initial swing, terminal swing, back-kick, knee lift etc. It is confusing and hard to describe. Running is a complicated activity that needs to be broken down into logical phases to explain how it works and allow meaningful comparison between individuals. The four phases described in this chapter are what I perceive to be the easiest way to explain how good running technique looks under close observation. When the running cycle is observed in slow motion there are key elements that are (relatively) easy to spot during these phases. As you become tuned into these, you’ll be able to observe them in real time running and photography.

I’ve arranged the discussion about the four phases into the sequence that will deliver the best outcome for someone seeking to improve their technique. Focus your attention on these early phases first when you begin improving your technique. You’ll see as we progress through the book, that I consider the phase just prior to ground contact to be the most important to get right – especially for the average runner. I describe this phase as preparation. I then discuss the other phases in sequential order: contact, back-swing and forward-swing. This is not to say that the other phases are not important - the late forward swing phase in particular, as it blends into preparation is critical to ensuring the leg tracks directly in-line with the hip joint with each stride. The elite 5000m runners below encapsulate the four phases in this shot.

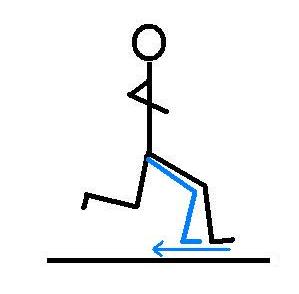

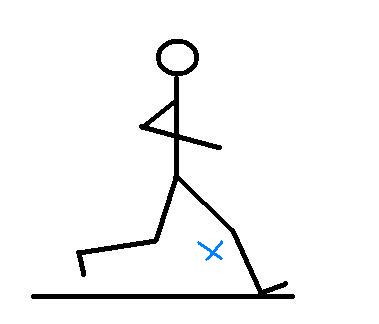

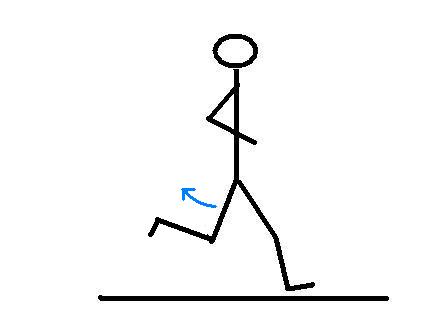

Preparation. The preparation phase begins when the forward swinging leg reaches its maximum level of hip flexion (thigh ahead of the body) and knee extension (straightening of the leg). At this point the athlete is in flight and not in contact with the ground. I’ve used stick-figure illustrations throughout to remove noise and add clarity.

We can see my stick runner is poised at the beginning of the preparation phase. The leg has ceased moving ahead of the athlete’s body and now begins to move, in a relative sense, back towards the runner and ultimately into contact with the ground. The key part of this phase is the activation of the hamstring and buttock muscles and initiation of slight (relative) leg movement back towards the body before the foot strikes the ground. Elite runners do this a lot, good runners do it a little and poor running technicians don’t do it at all. The preparation phase ends when the athlete’s foot makes contact with the ground. The example below shows a runner with excellent posture and position during the preparation phase.

This preparation phase of running marks the logical beginning of the running gait cycle and is the most important to get right. Unfortunately, it is also the hardest to master, requiring the greatest degree of coordination and strength to execute correctly. You need to activate your hamstrings and glutes before and as you strike the ground. This is not as easy as it sounds if you’re not natural well coordinated, but even a slight improvement can deliver massive benefits to your running. For example, a very small improvement could be to at least engage and activate the muscles responsible (buttocks, hamstrings and calf) for initiating hip extension and knee flexion. This will prevent over-striding and ensure that your leg strikes the ground stable and full of energy. The fact that your knee will be flexed with these muscles active also brings foot contact closer to your body mass. The effect is less braking, better shock absorption, increased leverage at the hip joint and release of stored elastic energy into the next stride.

This missing early hip extension (or at least lack of hip extensor muscle activation) is the single greatest problem for slower athletes and recreational runners. I’ve watched a lot of running in the past few years and there is no doubt in my mind that slower runners wait until they contact the ground (i.e. until they land) before activating these key running muscles. Aside from observing activity at the leg before ground contact, you can get a sense of this problem when a runner bobs up and down excessively. They sink at the hips when they land because the buttocks and hamstrings are not yet fully engaged and when they switch on, the runner pops up in the air.

The primary benefit of early activation of the hamstrings and buttocks (before ground contact) is that when the foot does contact the ground all the muscles around the hip and knee are pre-activated and engaged. The body is loaded with energy: the foot and leg contact the ground full of purpose, rather than flop down to the ground and then try and generate force to push off. The body is in a strong and stable position with all joints (hip, knee and ankle) protected, it makes for much more powerful, stable and injury resistant running. This movement also helps trigger the load and release of stored energy from the muscles and tendons.

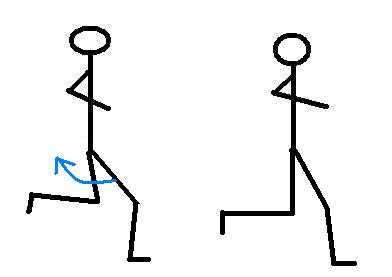

The ultimate objective of this preparation phase activity is the foot contacting the ground with the knee, ankle and hip joints flexed, but very stable. This posture maximizes potential for energy return and creates greater leverage at the hip joint. The muscles about the hip: buttocks and hamstrings - are very powerful. By having the knee and hip flexed, there is greater leverage and range of motion for these muscles to work. You can see the more upright running figure below has a much shorter range of motion available at the hip joint, compared to his counterpart who has greater flex at the hip, knee and ankle.

Here are some clearly observable good and bad technical features in this phase of running. On the good side we should be looking for:

The early initiation of glute and hamstring activation before ground contact (initiation of hip extension). This becomes more pronounced as speed increases and results in large changes in the position of the thigh as it moves back towards the body (Mann et al, 1986). The speed of this movement has also been shown to be a key measureable difference between national level and international standard 1500m runners (Leskinen et al, 2009). For regular runners any activation of the muscles and movement generated is a big plus.

The knee remaining slightly flexed even at the maximum point of leg extension ahead of the body. The extent of knee straightening will increase with speed during this phase. For example: while running at 5 minute km pace the knee straightens to about 40 degrees, whereas at 3 minute km pace the knee straightens farther to15 degrees (Mann & Hagy, 1980) and (Mann et al, 1986). Slower runners shouldn’t ever need to fully straighten their legs.

As speed increases, the maximum hip flexion increases (knee lift or leg drive) observable in this phase will also increase. At slower speeds 3.43 to 5 minute kilometer pace this has been measured at 50 to 55 degrees, at 3 minute kilometer pace things really pick up to 75 degrees and in pure sprinting 90 degrees, i.e. the thigh has reached a point where it is horizontal (Mann & Hagy, 1980, Mann et al, 1986 and Bushnell & Hunter, 2007). Normal runners definitely don’t need to have their knees under their chins to run with good technique.

The back extended (upright) - although not covered well in the research, from my observation the top athletes maintain excellent lower back curvature and upright posture of the torso. This is especially important for maximising the speed and degree of hip flexion and positioning the hip extensors (hamstrings and glutes) so they are ready to fire from an optimal position.

View slow motion video footage that compares activity in the preparation phase of running between a regular runner (me) and former elite 1500m runner Mark Gorski. You’ll note that even though Mark is not doing much running these days he still generates much more activity ahead of ground contact than me. In my video, the activation is evident, but modest, but I have at least progressed to having the right muscles active at the right time: this is a big step forward. You can also view footage of Dr Philo Saunders, the author of the foreword to this book, completing some short speed work. Again, Philo is an elite 1500m runner - the purpose of the video is to demonstrate the visible amount of hamstring/glute activation generated by an elite runner during the preparation phase of running. The elite 1500m runners in the shot below further illustrate the four phases of running.

While it was a challenge to find good research

to identify the critical elements of good technique in the

preparation phase, it was impossible to find any studies that could

shed much light on poor technique. Fortunately I have video footage

and photographs of me running before I began to improve my

technique. I can assure you I was doing almost everything wrong and

especially during this preparation phase. This, combined with some

slow motion video I have taken of other slower runners, gives me

some useful observations to discuss. As you might guess, the

elements of poor technique tend to be the opposite of those

exhibited by the better athletic technicians:

- There is no evidence of buttock and hamstring activation before

the foot contacts the ground.

- In the worst cases, the knee tends to be straight at the moment

before impact with the ground.

- The runner may collapse forward from the waist.

- The runner's thigh and leg may internally rotate or track towards

the centre line of the body.

Please review video taken of my old technique and see if you can spot these flaws.

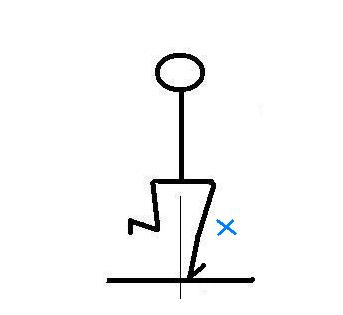

Contact. The next phase of running includes the critical moments between the foot first contacting and then leaving the ground. Without doubt this is one of the more controversial aspects of running technique and one that most commentators have very black and white views about. Some cling to the belief that runners should strike the ground with their heel first and then roll forward and over your foot. Others strongly believe that contact must be made forefoot first and avoid having the heel contact the ground at any time during running. A further group mandates a mid-foot strike as being the optimal landing pattern.

At the risk of adding to the controversy, I maintain that the precise posture of foot contact is less important for regular runners than generating early activation of the buttocks and hamstrings in the preparation phase and slight movement of the leg back towards the body as described above. This is because the discussion about heel-toe, forefoot, and mid-foot ignores whether the hamstrings and buttocks are engaged. It is extremely difficult to progress from heel-striking to neutral/forefoot contact without the intervening step of getting the foot to contact the ground closer to the body mass by activating the buttocks and hamstrings. Regular runners with a heel-striking pattern should be very cautious about deliberately trying to transition directly to landing forefoot or onto their toes.

At the elite level, there is a definite bias toward forefoot orientation, but this should not be mistaken for running on your toes. Elite runners tend to contact forefoot first and then their foot flattens and the heel does briefly come into contact with the ground as the foot, achilles tendon and calves load up with energy. They are able to do this because of greater strength and flexibility in the feet and lower calves and strong activation of the hamstrings and glutes to position the foot correctly prior to landing: something we can gradually work towards as regular runners.

In a boost for the barefoot running community, some recent research by Lieberman et al (2010) has shown that runners brought up with minimal or no shoes tend to float between a forefoot and neutral foot-strike pattern, whereas athletes from shoe wearing cultures tend to land heel first when running. But don’t discard your running shoes straight away. While it seems clear that a neutral/forefoot pattern is the preferred contact method, this can only be achieved safely if the leg and foot lands closer to the body mass under flexed knees and hips. The tendency to move towards a neutral foot-strike is then far easier to approach when good fundamentals are in place. You need to evolve towards it as a product of the developing excellent hamstring and glute activation, only then should you begin to consciously fine-tune the posture of your foot and ankle as you strike the ground. You also need to strength the muscles in the feet and lower calves, something that is best done gradually with the cautious introduction of shoes with less heel cushioning and a flatter profile than you are used to - more on this later.

In theory a landing point under the body mass rather than ahead also sounds good, but even elite runners land with their foot ahead of the body mass. Again of more importance is the activation of the glutes and hamstrings before contacting the ground (Leskinen et al, 2009). The elite 5000m runner below has clearly landed ahead of his body mass and has his foot (forefoot and heel) in contact with the ground. What is also evident is massive activation of the hamstrings.

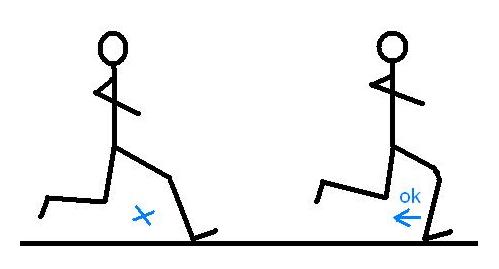

Good technique. There’s a lot to absorb and I’ll step through it in more detail starting with the initial moment of ground contact. The foot may contact the ground ahead of the body mass if hip extension has been activated by firing the glutes and hamstrings - see picture below. The foot should contact under or behind the knee, not ahead of it.

The knee must be bent or flexed and the foot aligned under the flexed knee. The hips must be held in a flexed posture to absorb and release energy and generate powerful leverage into the next stride. The back should remain upright to help maintain good activation of the buttocks. While the hips should be flexed, the buttocks should not drag along the ground - this would be symptomatic of poor buttock muscle activation.

In my opinion, the optimal foot contact posture for regular runners is neutral (main picture above and below). This is a stable and powerful contact pattern that will allow you to eventually evolve to forefoot orientation. That said, I’m not completely dogmatic about this. A moderate heel toe or forefoot oriented posture (as per the inserts) will also work well for most runners provided early hip extension has taken place. Forefoot oriented runners should always allow their heel to touch the ground. Don’t beat yourself up about trying to land forefoot or worry that you still kiss the ground lightly with your heel. It’s more important to activate the body's shock absorbing and power generating muscular and tendon systems by firing the glutes and hamstrings. The runner below illustrates excellent technique during contact.

The key is to make a rapid and strong transition from dorsiflexion (toes pointed up) to plantaflexion (toes pointed down) so the foot leaves the ground earlier and transfers more of the power of the buttocks and hamstrings into the stride. This means the foot actually stiffens during contact to create a springy stable platform. By the time the foot passes under the hips, most of the work in the stride has been done: at this point the body begins to return the energy loaded into it during the early phase of contact.

Knees and hips do not collapse during ground contact. Better runners maintain joint stiffness because they are stronger - this enables them to benefit from greater levels of energy return as well as losing less energy to lateral movement at the hip, knee or ankle.

The position of the thigh and foot in relation to the hip during ground contact is the second most important element of good running technique. When you see a runner with their foot positioned closer to under their hip than the body’s midline you know they are stable, economical and powerful (see picture below). A runner with this contact posture will also be far less likely to suffer lower leg, ankle and hip injuries.

The foot should begin leaving the ground very shortly after the thigh passes into true hip extension (thigh moving behind the body). This helps keep ground contact rapid and short. Runners with good buttock activation and strength will leave the ground earlier and more powerfully: pushing the torso ahead of the hip into the next stride.

Problems develop when extremes are present at the hip, knee and ankle postures at initial contact and during the full support phase of running. Many of these issues have their origin in the lack of engagement of the buttocks and hamstrings prior to contact with the ground in the preparation phase of running.

Contact with a static straight leg, well ahead of body mass is a recipe for disaster (see picture below). The runner’s hips are less flexed the knee straight and usually the foot held in exaggerated dorsiflexion (toes point up). In this posture the body’s shock absorption systems are not engaged and the landing will be heavy and painful. Virtually no energy will be returned by the body and the ground contact will be long. Runners might want to search for extra stride length, but this not a good way to get it. The amount of ground covered in each stride improves by a stronger, compact bouncy stride rather than a dead, elongated and slow stride pattern.

Further issues arise when the buttocks are not sufficiently active prior to and during contact with the ground. The glute muscles help draw the thigh under the hips as they engage: when they do not fire, the landing posture tends to look like the picture below. Instability at the hip and twisting of the lower leg, ankle and foot are the end result (Kawamoto et al, 2002). The popular myth that pronation is caused by foot type (e.g. flat feet) is dispelled when you realize that the actual reason is instability and lack of glute activation at the hip joint, which puts the lower leg, ankle and foot into weak positions. Less active buttocks also mean less power, long ground contact and slower transition from hip extension back to hip flexion between the back and forward swing phases. This problem can impact the entire running cycle.

While foot and ankle posture for regular runners is less important than an active landing by switching on the glutes and hamstrings, there is one area that is problematic. Runners who remain on their toes all the way through the ground contact phase subjecting the foot and lower leg to greater forces and more twisting. This posture is less stable and reduces the ability to use the foot as a stiff platform to launch into the next stride.

A further problem is an athlete who first contacts with an exaggerated heel strike, the transition to plantaflexion is delayed meaning ground contact will be longer and the stride less powerful. It also delays the ability of the foot and lower leg to help absorb landing shock.

Over extension of the hip joint is a major sign that the stride is lacking power from the glutes. The inability of the gluteus maximus in particular to activate correctly combined with insufficient strength allows the torso to pass over the hip, rather than being propelled ahead of it. In this picture below we can see the thigh has passed into hip extension (behind the body). The ground contact will be long and the hip flexors overstretched delaying the return of the leg into hip flexion (thigh ahead of the body). Runners exhibiting this pattern will have slower leg recovery and an inability to change pace under pressure. Runners with this pattern also tend to lean forward at the waist - a further consequence of weaker glutes.

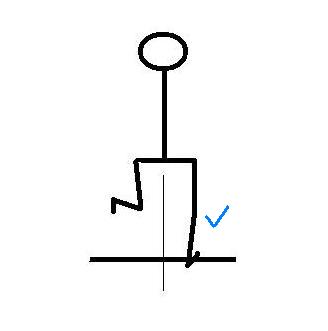

At the very last moments before the foot leaves the ground, we can also see whether the plantaflexors (calf, lower leg and foot muscles) are engaged to make the foot into a springy and stable platform from which to apply force. While the foot flattens at the initial point of contact to absorb shock, it must then quickly load with energy and stiffen to drive the body forward and make use of the work done by the hamstrings and glutes. If the foot is floppy as depicted below, much of that energy will be lost.

This flaw often coexists with over extension of the hip and lack of glute activation and contributes to longer contact time with the ground (Bosch & Klomp, 2005). As a left field piece of supporting evidence, Stefanyshyn & Fusco (2004) found that by inserting a stiff carbon fiber plate into the running spikes of sprinters their performance actually improved. Now I know why most shoes include a degree of stiffness as you try and bend them from front to back. This is a good reason to look at minimalist shoes such as the Nike Free as it encourages the natural plantaflexion strength in the foot and lower leg to develop. When you put your racing flats back on, there is the double benefit of stronger feet and stiffer shoes.

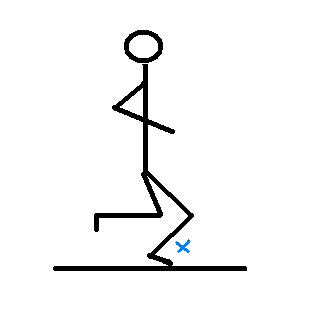

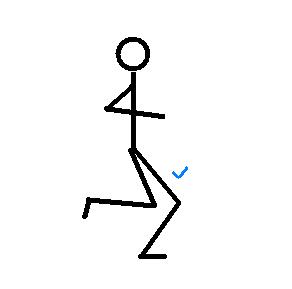

Back-swing. The back-swing covers the moments between the foot leaving the ground and the hip reaching its maximum point of extension behind the body. You can learn a lot about everything leading up to the back-swing phase by observing what happens to the leg after it leaves the ground. This phase allows you to almost see inside the body and make assessments about how well and strongly certain muscles are being used by the runner.

Again, this phase needs to be as efficient and fast as possible, the goal being to return the leg into hip flexion without delay. It stands to reason that the earlier the foot leaves the ground, the earlier this phase begins and ends, so it is also influenced by the early activation of the glutes and hamstrings during the preparation phase. Power in the stride generated by these muscles is transferred efficiently to the ground via a strong and plantaflexed foot. This loads up the hamstrings, calf, lower leg compartment and achilles complex full of energy so that once the foot leaves the ground and maximum hip extension (leg behind the body) is achieved, a certain level of recoil occurs that helps flex the knee during the back-swing phase. This makes the leg a shorter lever and provides impetus for it to return into hip flexion ahead of the body. The faster the runner is moving, the more knee flexion will develop, bringing the foot and lower leg above the horizontal and towards the butt. A tight swing action makes for the most efficient running technique. Slower runners don’t need to kick their butts with their heels and even in elite runners this pattern only develops in faster running. This sequence below is taken from video footage of elite 5000m runners in the closing 800m of a 13.10 performance. It illustrates the backswing phase commencing (2nd runner), maximum hip extension (1st runner) and the beginnings of transition into forward swing (4th runner). The third runner's leg is in forward swing and well folded towards the buttocks.

Tighter techniques tend to be more efficient. If you see a race with someone sitting on the leaders with a more organized action, look for when they lengthen their stride and kill the competition in the later part of the race. The kicker is usually a better technician; they invariably don’t have to work as hard aerobically as their competition, running within themselves with strong compact strides that deceptively will deliver the same stride length as their victims who work over a wider range of limb motion. When it comes to the crunch, the kicker applies more force into their stride, at the same stride rate, causing a lengthening of their stride and significant increase in speed. Usually the gutsy runner who’s done all the pace setting can’t respond as they’ve been running in their top gear the whole race, all they can do is try harder, which usually involves over striding - even less efficient than their speedier competition.

The back-swing phase needs to be as rapid and tight as possible. As the foot leaves the ground the leg is close to full extension and rapidly commences flexing at the knee as the forward swing phase commences. How quickly and how far this flexion occurs can help you determine the quality of the runner’s technique. The tighter the angle of the knee, the shorter the length of the leg to bring forward into hip flexion, moreover, this rapid action serves to ‘turn-over’ the leg into the next stride with an almost pendular motion. As an extreme, keep in mind the sprinters studied by Mann & Hagy, (1980) and Bushnell and Hunter, (2007) do not actually make it into true hip extension. That is, the swing phase and pick-up of the leg into the next stride was completed before the thigh bone makes it past the midline of the body. In distance runners the situation is not so intense, hip extension being desirable in faster running and more economical over the longer haul.

Problems occur when the back-swing is too elongated and the hip becomes over-extended. This causes a knock-on effect into delayed forward-swing that is explained in the next paragraph. This posture is also indicative of limited glute activation and strength. A very low back-swing indicates limited hamstring activation and has negative consequences into forward-swing causing limited knee drive and less hip flexion. Even at elite levels this can make a big difference as Leskinen et al (2009) found in their study comparing national and international level 1500m runners. The national group demonstrated a more elongated back-swing phase delaying the onset of forward-swing and rapid return to hip flexion.

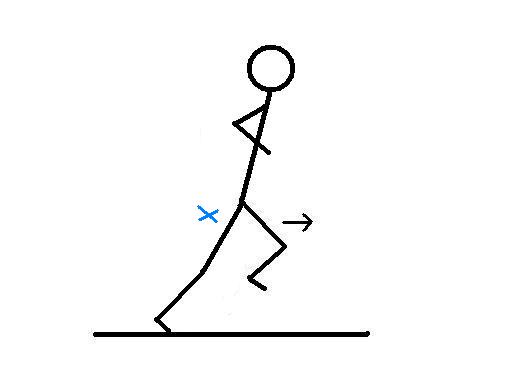

Forward-swing. The forward-swing commences immediately the movement of the thigh behind the body stops and the leg then begins to track forwards into the next stride. This phase ends when the swing leg stops moving forwards and begins moving back towards the body: that is the beginning of the preparation phase and the completion of the running cycle.

The swinging leg overtaking the support leg quickly is a strong indication that the transition from hip extension (leg behind the body) back into hip flexion (leg swinging ahead of the body) and into the next stride is occurring efficiently. This should happen before the support foot passes under the body mass. In this illustration we can see the swing leg recovery from back swing to forward swing has taken place rapidly and allows the runner to be quickly into the next stride.

Slow transition into the next stride is also easily observed when the swing leg transition into forward swing is delayed. The runner then appears to be stretched out with their leg trailing a long way behind the body. The support leg then has to wait for this slow recovery lessening stride frequency and running economy.

Stride rate or cadence. One of the more easily observed indicators of technical issues is the stride rate of a runner. The elite rating observed by Jack Daniels at the 1984 Olympics of 180 strides per minute (Daniels, 2005) serves as a useful benchmark. A slow rating (less than 170 strides per minute) could be indicative of problems. However, this is another area not to fixate on, over-focus on cadence can lead to super short strides that are incomplete and lack power. Rather than think about increasing stride as a means to improve your technique, consider it a benchmark that can be used to evaluate your running technique.

Arm swing. The role of arm swing in running is yet another area of running technique that is controversial. Veteran coach Ron Warhurst, who amongst many other achievements, is perhaps most well known for being the coach of 2008 Olympic 1500m silver medalist Nick Willis. He is also an arm swing advocate. Warhurst belongs to the school of thought that believes arm swing helps or even regulates the stride of the runner. On the flip side of the argument is the legendary Arthur Lydiard who said “when I train athletes I try to make their legs go faster, not their arms”. I think there’s likely room for both views to be useful depending on the athlete. If a runner is too tight and their arms are out of synch with their legs then Lydiard relaxation could help, but conversely if you’re low, slow and don't have a powerful stride, then perhaps a bit of Warhurst arm action could be the stimulus needed to help generate some more purpose in your running.

What I’ve found through experimenting is this: I think Warhurst is right, the more I think about pumping my arms and using the bigger back and chest muscle to help this drive, the quicker the stimulus for my leg and foot to get back on and off the ground. Overall the change tends to deliver more power as well. A few years ago when Dr Philo Saunders reviewed my old running technique, he did point out that I needed to use the bigger chest and back muscles to improve my arm drive. Unfortunately I didn't put this advice at the top of my list of problems to work on. I think in hindsight, if I'd focused as much on my arms as I did on my legs, I may have been able to make greater improvements in my running. This is something I'm really getting into now.

I recently had the good fortune to see 800m world record holder David Rudisha run in Melbourne and I can safely say that he could be the poster boy for arm swing advocates. Rudisha's arm drive so high that he could easily touch is nose. Admittedly, he's not a longer distance runner, but it does demonstrate that healthy arm drive could play a role in better performance. I did not find significant research into arm swing for distance runners; however I put the caveat that there is likely to be more information about the topic in relation to sprinting technique. This is definitely an area that I will be looking into further in the future.

Summary. Our techniques may not yet exhibit the excellence of an elite athlete running at high speeds, but even small steps in that direction will yield significant improvements. Those of us coming off a lower base of performance have significantly more opportunity for upside improvement than someone who can already run 30 minutes for 10km. I’m very happy to be in a position where I can see the possibilities of further improvement through running more efficiently and strongly rather than just training harder or running more miles. It’s very exciting to run faster knowing you didn’t have to work any harder in training to achieve that result.

In the next chapter I will discuss and overlay the muscles involved in generating good running technique, this will then give you the deeper knowledge needed to begin building a better technique through practice, strength and coordination training and mental cues.

****