A different view on running. The more I research running technique the more convinced I am that running is a movement built around strength and good coordination. The ability to endure and run longer distances does come with accumulating training volume over many years. However, this should not become the main focus until the strength and technique of a runner is sufficient to sustain the skill of running for shorter durations. This philosophy is not necessarily at odds with traditional training methods used successfully by many runners over the years. If your basic running mechanics and technique are good then an approach that gradually focuses on building mileage, strength and then intensity can work very well.

The problem for many recreational and club runners is we don’t realize that we’re not strong enough or have adequate coordination to run with a satisfactory technique. This can lead us into the trap of running longer before we are strong and skilful enough to sustain good technique. The result: injuries, modest performance improvements and the boring slog of running a lot of slow miles. If a runner with poor technique does more and more training without improving those suspect mechanics, then injury is going to be a likely outcome. The additional volume can reinforce bad habits and subject the body to repetitive stress injuries because the technique puts various joints, muscles, bones and tendons through unnatural ranges of motion.

As runners we always think about training harder and longer to make us better, bring down our best times and even improve our running mechanics and economy. I’m unsure how this can work, except if you have the good fortune to be born with the talent and resilience to adapt to this approach. Doing more of something badly is not a recipe for success in my opinion. Runners can benefit from adopting a different philosophy in constructing their training programs. One that emphasises developing the strength and coordination needed to sustain good technique before adding significant training volume and intensity. I explain this further in the final chapter of the book. In this chapter we examine the general benefits of strength and coordination training and the specific benefits for regular runners looking to improve their technique and avoid injury.

Elite running and strength training. Elite and well-trained runners experience significant benefit from adding strength training into their running programs. There are numerous studies that have proven this in controlled trials (Paavolainen et al 1999, Saunders 2006, Berryman et al 2010). The top ranked 10,000m runner for 2010, Josphat Menjo of Kenya cracked the big time at age 31 after adopting a serious approach to strength training (Butcher, 2010). In the space of two weeks he ran 12.55.95 for 5000m, 3.53.62 for the mile and 26.56.74 for 10,000 meters. I was fortunate to witness Josphat easily winning the Australian men’s Zatopek 10 in December 2010. He belies the popular myth of elite distance runners as skinny pipe-cleaner types - he might be lean, but he is a strongly built athlete. The winner of the women’s Zatopek 10 at the same meeting was Australia’s Eloise Wellings, a strong and powerful runner with excellent technique, who focuses plenty of attention on her strength training regime.

Strength training for regular runners - should we just copy elites? I believe for regular runners the benefit of strength and coordination training may be even more profound than for elite athletes. Talented athletes benefit because they are adding icing to their well-baked technical cake. For an average runner the benefits may extend into bigger improvements by increasing the ability to run with better technique, coordination and posture. Many runners should think about strength and coordination training as a means to develop a good technique. Only after this is achieved should we begin to seriously increase training volume and intensity.

The type of strength training contemplated becomes important, especially for beginner or less technically gifted athletes. Elite runners benefit from plyometric or explosive type strength training. However, I believe this is too challenging for someone who has yet to learn the foundation of a good running technique or developed a good strength base. For an elite athlete, their neuromuscular pathways and movement patterns are already sound; therefore they are training to enhance what they have already mastered.

For someone who is struggling with technical problems in their running it is unlikely that hard-core plyometric and explosive weight training is going to be of much benefit. In fact, I would argue that for these runners, myself included, the risk of injury initially outweighs any benefits that might accrue. For regular runners basic strength and coordination training with an emphasis on coordination is far more important to your initial development of better running technique. So just how much will an average runner improve by using this type of training to build a sound technique? I argue that improvement can be profound.

Making the case for strength training for regular runners. The objective of this chapter is help you understand why strength and coordination training is important to developing a sound running technique. The reading I’ve completed in this area is so compelling that I’ve added to my motivation to complete more of this type of training. The overview below will hopefully get you excited about adding strength and coordination training into your own running program. If you are a coach, it will give you the theory to convince your athletes that going to the gym has a specific role in making them more accomplished runners: it can make them faster, more technically skilful athletes.

This chapter covers:

- why the worse

your technique, the more you need strength training;

- how strength and coordination is gained by neurological

adaptations;

- why awareness of muscles and movement builds strength;

- specific movement patterns and postures and why they make you

stronger;

- why better coordination between assisting muscles increases

strength;

- how strength is gained through changes in physical

attributes;

- the impact of strength and stiffness of tendons and connective

tissue; and

- where strength and coordination is needed most in running

technique.

If your running technique is bad you need strength training more than a talented runner. You often read of interviews with elite runners who talk about how many miles they are covering in training. Many of the popular coaching philosophies and elite coaches espouse the benefits of going longer. These guys and girls are covering 100 miles (160km) per week on a regular basis. For runners like you and I who think running 25 - 43 miles (40-70 km) a week is a decent amount of running, this volume is an almost unthinkable amount of training to contemplate. But that’s what you need to do to get better, right? Well, maybe if you want to make the Olympic team perhaps, but even then I’d argue many elite runners tend to over-train.

For normal runners the first thing is to get your running technique to a good level of competence. Any attempt to run big volumes and intensities without first getting your mechanics right is destined to end in regular visits to the physiotherapist, swimming laps or worse, water running! In chapter 4 and chapter 5 I described what good running looks like and the muscles responsible for driving those movement patterns. To be able to propel your body forward while stabilising and supporting your joints throughout the running cycle requires you to be strong. As we’ll discover, getting stronger is in part about learning to move efficiently and well. Therefore practicing running-like movements in the gym or at home is a great way to train your body into better technical habits.

Adopting a strength and coordination program (it can be done at home with no equipment if you hate the gym) helps you build strength and allows the muscles, their connective structures and your central nervous system to get better at performing the running movement. Here strength comes about by two mechanisms; learning (neurological) to do the movement faster and more efficiently and with absolute strength from your muscles increasing in size and strength (hypertrophy and morphological adaptations).

For me and other runners the harsh reality is we can't run well for a sustained period until we get strong and improve our intramuscular coordination. Strength and coordination exercises are a regular part of my routine, two sessions a week, and I think I would benefit from more. Elite training squads do up to five strength sessions of different types per week. Like you I don't have the time to hit the gym this often, but it shows how important the best runners think strength training is. These sessions don’t need to be long or boring; they can be completed in 20-30 minutes. Doing a small number of different exercises well is much better than doing many of the same poorly.

Don’t worry about looking too muscular or getting heavy. If your running style frightens small children and animals then it might be time to think about how strength and coordination training can help you learn, adopt and maintain a superior running technique. As I’ve hinted the benefits are as much about learning to activate and coordinate the muscles needed for running than in trying to look like a latter-day Ben Johnson. If you are concerned about gaining weight or looking too muscular - don’t be. If you are doing even a modest amount of distance running you will simply not have the spare calories to put into building big muscles. Body builders couldn’t run to the corner store to pick up a carton of milk. The reason is they do little if any cardiovascular training - they need all the available food and energy they consume to be available to build big muscles. A good deal of the energy you consume is expended on your regular running, so there’s little, if any, left over to grow giant biceps.

Counter-intuitive as it may seem, building some muscle mass into your body actually helps you maintain a lean physique, even if you’re forced to lay-off or reduce your running through injury. The reason for this is that muscle is active tissue and requires more energy to function. You burn more calories when at rest, sleeping, working at your desk and even watching television. This is advantageous if you are coming to running as a means to get fit or you are carrying a little extra weight from hibernating over a long northern winter. You’ll find you are able to maintain your weight or even lose excess fat while running fewer miles. You don’t need to run excessive volumes just to maintain your weight - the strength training will take care of this for you.

I speak from personal experience, I once reached 94 kilograms, the weight loss program I undertook initially was focused on riding a bike, rowing and jogging at high volumes - yes I lost some weight, but it took months and was hard work. When I wised up and started doing some strength training the rest of the fat dropped off in double quick time. I’ve now been able to maintain my weight in a range of 70-74 kilograms for about ten years. Even during times when I’ve been injured and not running the weight does not come back on because of the increased muscle mass I carry. You’ve seen pictures of me; I’m hardly a body builder so it’s nothing to be afraid of.

Run strong not skinny. There’s a big difference between a strong, lean athlete and a skinny runner with limited muscle mass. The strong runner is injury resistant, powerful and dynamic in their movement; the skinny runner is frequently injured, suffers stress fractures and has a weak stride. Do not be tempted to deliberately set about being as light as you possibly can. This is a dark path in running that unfortunately many female and some male runners choose to follow. This is not the answer to better running performance. The best runners in the world are strong - they may look lean, but on closer inspection they carry a very high proportion of muscle mass on their bodies.

There’s probably not a better example of a strong runner than American Chris Solinsky - he actually weighs about the same as me, which I find amusing because he’s frequently talked about as being heavy and big. There’s not too many 6 foot 1 inch guys getting around that can run a sub 13 minute 5km. Yes, he is heavier than some of his shorter competition, but the reason he can compete and is touted as a hard trainer who does not get injured is he's as strong as an ox. He is also part of Jerry Schumacher's Oregon training squad that under the guidance of Pascal Dobert completes five sessions of strength training per week. Watching him close the last 800m of his sub 27 minute American record run in 1.56 was exciting - you need to be strong to run like that at the end of a 10,000m.

Being strong in running is not just for men: in Australia, national 10,000m and 5,000m champion Eloise Wellings has come back from a well documented struggle against low bone density and multiple fractures caused by running at low body weight. You wouldn’t know it today as she is such an impressive and powerful athlete. When she lined up against the competition two years ago at the Zatopek 10 she was the strongest runner in the field. Like Solinsky she easily covered all the moves of the leaders during that race and was able to pull away with a decisive last 400m to win the race and the national title. It's reasonable to say that being strong is more important for females than males as working on strength helps reduce the risk of osteoporosis by increasing bone health and strength. For further evidence of the importance of being a strong woman look no further than leading American runners Kara Goucher and Sharlane Flanagan.

How strength and coordination is gained by neurological adaptations. Neurological adaptations are simply those brought about by better control or use of our central nervous system to activate movement patterns. What researchers found is that increases in strength come about very quickly and are much greater in proportion than increases in actual muscle size (Folland & Williams, 2007). This means there are other factors at play in gaining absolute strength than just having bigger muscles. Most of these appear to be driven by the body learning to perform a movement better or more efficiently. The research shows that these improvement arrive early in a strength and coordination program, so the news is very good for those of us (and who isn’t?) impatient for results.

This tells us that there is a good argument for regular learning of new but related exercises in the gym to mix things up and keep strength gains from stagnating. This means you should be on the lookout for variations in the type of exercises you do. This does not suggest taking on exercises completely unrelated to running - just vary things around the central theme of running. For me this involves training my hamstrings and butt in at least half a dozen ways twice a week: squats, dynamic single leg bridging, single leg squats, step-ups, leg press, dynamic back extensions etc. All of these movements have some relationship to running, but variations in posture, movement range, weight and speed of movement all change things up a little to stimulate improvement.

Awareness of muscles and movement builds strength. Before I started reading articles on how the body adapts to strength training I noticed some curious things about how I was able to perform certain exercises in the gym. Almost every time I adopted a new exercise I had to go through a number of stages before I could get to the point where I could say to myself honestly that I was doing the technique correctly. Luckily I'm smarter than I was in my twenties. This means I don’t immediately grab the heaviest barbell on display and try to lift it no matter how badly I was cheating by using the wrong muscles and momentum. I now start with a weight that is light enough so I can practice doing the movement properly first. Or for many of the exercises I do there is no weight used at all - only the body. Note: there are people in their twenties who are smarter than I was.

The first few weeks of training with a new exercise will generally see me trying to master the movement. I’ll use the leg press as an example as it’s a piece of gym equipment that most people are familiar with. The process is the same for any exercise you will find later in this book. I used to make use of this machine trying to get massive quads. I now know that by varying the position of my feet on the plate that I can change the emphasis of the exercise to work the hamstrings and the butt. You do this by putting your feet higher and wider (almost at the top) of the plate and by adopting a slightly duck footed pose. You then push through your whole foot trying to initiate the movement from the butt and the hamstrings.

The first couple of times I’m trying to get this right, but my quads want to kick in and help so I can hardly feel much burn in my butt. I start to experiment with lighter weight - I can’t lift as much this way as in the traditional posture on this machine that focuses on the quads. So I back the weight off about twenty kilograms and concentrate even harder, this time I start to get it, I exaggerate the position of my feet even higher and a bit wider. I now have no choice but to push with my butt. Slowly the plate moves and this time my butt is doing the work, after two sets of 12 repetitions I have a burning sensation down my butt and at the top of my hamstrings. This feeling lasts for a couple of days and strangely that night I run easy and it feels great, really like my hamstrings and butt were much more engaged that normal.

This learning process for each exercise varies and takes longer for more complicated movements and especially those that require balance i.e. single leg squats. With these types of exercises it might take a few weeks of not doing it well before you start to get it. There is an extra stage that involves turning on and strengthening muscles that may not have been used for a long time.

When I was learning single leg squats (and it continues) I found that in the first weeks I was very wobbly, my hips were rotating and popping out to the side and the only muscles that seemed to be getting a workout were my quads. So while I could squat up and down flexing and extending my knee, my hips were completely out of control. It took a number of weeks, maybe even a month or so, to get to the point where I could do this movement well.

I believe this is partly neurological and also due to the fact the some of the stabilisers needed were not strong enough to begin with. After a while and by doing some focused work on those stabilisers (glute medius and vastus medialis) I could feel them begin to engage while I was doing the squat - maybe before they were too puny for me to notice and to switch on properly. So now a single leg squat involves activating my glutes (maximus and medius) and keeping my hips back and down a little as I do the exercise. I now get a burn through the stabilising muscles and the vastus medialis (medial quad that attaches to the inside of the knee). Those two muscle groups are now working in synergy to make the squat happen without adverse and wasted movement at the hip. Over time I’ve been able to add more force and speed to these movements because I can maintain better posture and more optimal set joint positions and angles. If you think about it this is exactly what you want to do in running too.

Specific movement patterns and postures. In their review of the scientific literature Folland and Williams (2007) found a number of studies that recorded results indicative of strength gains being made because of the mind and body learning how to hold and maintain a specific posture. These postures were shown to allow the greatest expression of strength for a certain muscular movement pattern. Further, there is compelling evidence about the muscles exhibiting greater strength as a result of changes in joint angles and positions. These factors suggest that part of the explanation of strength gains made in addition to increases in muscle size is linked to learning the optimal way to hold the body stable and in favorable postures to maximize strength.

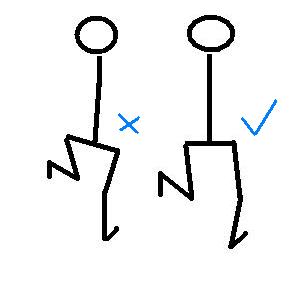

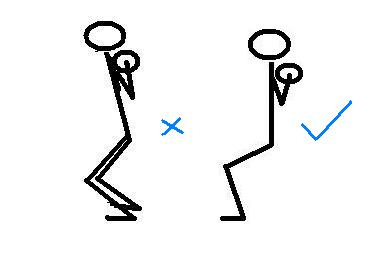

If we link this back to running, this is about learning the correct posture and movement patterns to execute good running technique. In chapters 4 and 5 we discussed how better runners were able to maintain good knee and hip positioning resulting in flexed hips and knees at key moments in the running gait cycle such as preparation and contact. The knees and hips are primed at optimal angles to absorb and unload force. It is difficult to just lace up your running shoes and just decide you will run with this way. You need to learn these postures and movement patterns by training and strengthening the muscles responsible using exercises with similar movements to running. For example: squats teach you to deploy your glutes in concert with your hamstrings.

Learning new postures to increase strength. Initially I couldn’t do a squat properly, tending to dip forwards at the knees relying on my quads to push me upright. As I learned to sit back, spread my feet a bit wider (similar to the leg press technique) lowering my buttocks towards the floor with a good curvature maintained in the spine, I was able to start engaging the glutes and hamstrings. As I’ve progressed I have focused on making the movement slightly faster and more bouncy rather than add weight. Again, this is an attempt to mimic the conditions of running. When I’m running well there is a similar feeling of bounce coming from my hips and buttocks. The more I practice it with strength training, the better I seem to be able to replicate that feeling in my running.

If I return briefly to the concept of greater strength being available at specific joint angles - we can see in running that at initial contact the hips and knees are both flexed. In my earlier description in chapter 4 I speculated with the support of Bosch and Klomp (2005) that this meant there was greater leverage available at the hip joint. What we have just learned is that not only is leverage better when in that position or posture, but muscular strength is also greater. As an example from the gym, if you’ve ever used a hamstring curl machine (and I don’t recommend you should) you’ll notice that it is hard to curl the weight when starting with straight legs. If you begin the movement with slightly flexed knees your hamstrings are in a much stronger position to move the weight.

Training for coordinated movement. Most of the muscles involved in good running technique actually work hard over a relatively short range of motion. This is due to the maintenance of flexed knees and hips at crucial stages of the running cycle such as preparation and contact. The hamstrings, as we have seen, are the dominant muscles involved in running, being active over 60% of the gait cycle. The hamstrings are also specialized muscles because they cross two joints, the hip and knee, this means they have two roles - to extend the hips (push your thigh back toward your body) and flex the knee (raising your heel towards your buttocks). Therefore it makes sense to train these muscles to do these tasks concurrently and in similar ranges of motion when in the gym.

This means avoiding the popular hamstring curl which seeks to isolate the hamstring to only flex the knee - by doing this exercise you are training your body to do something that it never does in running. There are other more beneficial exercises such as squats; dynamic single leg bridging and dynamic body weight back extensions that more closely mimic running mechanics and postures. Note: all of these exercises can and should be performed in limited ranges of motion - this makes the exercises more dynamic in nature, strengthening and training the muscles to work in a similar way to running. For example when using a leg press machine you should never fully extend your knees or flex your hips too deeply: work in a shorter range with more powerful bouncy movements as your strength and coordination improves.

Coordination and strength of assisting muscles. It’s easy to focus on the benefits of training the major and most obvious movement patterns and muscles involved in running, but we mustn’t avoid the stabilising and synergistic muscles that allow the big stars to perform their act to perfection. These muscles are the support crew; ignore them at your peril as they form the enabling foundations for many movement patterns. Without them your strength is unlikely to be fully expressed as wasted joint movement robs you of valuable energy expended in your stride. Learning to switch these muscles on at the right times is one of the key benefits of strength and coordination training. Exercises like single leg squats (and running) need all the stabilising muscles to kick in and help.

Antagonist co-activation. Let’s all pull together in the same direction. If only it were that easy. I’d never heard of antagonist co-activation before I began researching this book, but I’ve certainly experienced it and am still working on fixing this problem in my running. It means the antagonist muscle is firing at the same time as the agonist or prime-moving muscle. In running, this could be a situation where the hamstrings (agonist for hip extension and knee flexion) have to fight against the premature activation of the rectus femoris (antagonist hip flexor and knee extensor).

Running is a complicated activity involving all of the body’s joints and muscles, each playing their specific agonist and antagonist role - especially the muscles responsible for working the hip, knee and ankle joints. It stands to reason that if we can train each of these muscle teams to fire at the right times in synchronization, running would become easier and more energy efficient. Folland and Williams (2007) speculate that “during more complex whole-body movements, the level of antagonist activation may be greater, perhaps providing more opportunity for a reduction in co-activation with training.” I can only agree with this line of thinking because to date this has been my exact experience, not only in running but in the gym practicing and trying to perfect certain exercises, slowly learning to turn on certain muscles at the right time and turn off those that are jumping in to help at the wrong time.

In running, this is an important problem to solve. Co-activation of the rectus femoris (on the right side of my body) as I have discussed in my own running reduces the range of motion and height of my back kick (you can see this in chapter 6) as well as fatigues the agonist hamstrings prematurely. It’s a vicious cycle, the hamstrings get tired from pulling against the rectus femoris and then the rectus femoris gets sore and tight from activating at the wrong time. The tightness then serves to perpetuate the problem further by restricting the range of motion in the swing phase of running.

How strength is gained through changes in physical attributes. This is the easier stuff to grasp and understand. I’ve now got stronger hamstrings and butt muscles so I can run faster for longer with better technique. There is no doubt about the direct and relatively obvious benefits of stronger muscles in your running, however what we have just learned is that there are just as many (if not more) benefits from training your muscles and nervous system to work smarter and in a more coordinated way. If you’ve got big hamstrings from doing machine leg curls week after week you will see nowhere near the improvement in running performance than if you had trained your hamstrings using more functional, running-like exercises. You may also subject yourself to a greater risk of injury caused by loss of coordination in this powerful muscle group (Bosch & Klomp, 2005). This view is supported by Australian Rules Football Coach Ross Lyon, who when asked why his team suffered an abnormally high rate of hamstring injuries, responded cryptically that their strength program lacked “meat and potatoes”. What he meant was they didn’t do enough basic exercises such as squats which require good coordination between the glutes and the hamstrings.

Size (hypertrophy) and composition of muscles. The muscles tend to respond to weight training in accordance with the different muscle fibre types. Type 1 (slow twitch) and Type 2 (fast twitch) fibres are present in different proportions from person to person, however the absolute number of fibres is thought to be determined at birth and does not change through training (Cash, 2000). In their literature review Folland and Williams (2007) summarised a number of studies that suggest that type 2 fast twitch muscles fibres tend to grow and respond more quickly to strength training than slow twitch type 1 fibres. This is good news for slower endurance runners because in the early phases of our strength and conditioning training we may be able to pick up some much needed speed. Because the fast twitch fibres fire about three times faster (Cash, 2000) than slow twitch fibres there might be a case to be made for absolute speed increasing but also an easier path to increasing our stride rate towards the magical 180 strides per minute (Daniels, 2005). This increased speed within our stride (faster cadence or turnover) has been linked to more efficient running technique.

In terms of developing our muscle strength and endurance, slow twitch fibres have been shown to also respond well to endurance training in the longer term. Conventional wisdom also suggests that training muscles with lighter weights and larger numbers of repetitions would target these endurance fibres more specifically than their faster more growth oriented counterparts. However, I’m not sure there is actually much evidence around to support this argument. My base position remains to focus (especially early in your strength training) on doing exercises with lighter weights and with greater repetitions. This is more effective at learning the correct muscle movement patterns and establishing neurological pathways that will stick with you when you’re under pressure on the running track or lifting heavier weights as your strength develops.

Think about mixing and matching your approach after establishing a very strong base and have confidence in the movement patterns and postures your have developed in the gym. This might take years rather than months so be patient and let your body slowly adapt, learn and strengthen over time. Just like running, consistency in weight/resistance training is more important that trying to stack extra weight onto the barbell every time you approach the squat rack.

There is also an argument about which muscles you should target for increased size - generally this would be dictated by the type of exercises you choose to do. If we follow the rationale of focusing on running-like movements in the gym we should add muscle strength around the hips, buttocks and hamstrings and to a lesser extent the stabilising quadriceps muscles. Bosch and Klomp (2005) argue that you shouldn’t try and add muscle bulk to the calves because this is adding weight away from the centre of the body mass and therefore puts weight at the end of the lever arm of the leg. This is a logical approach considering studies completed by Jack Daniels have found that adding weight to running shoes is costly to your running economy. Another reason to be cautious in trying to target your calves specifically is that doing calf raises, which are an isolation exercise, is different to the natural motion of running. The plantaflexion in running is more like resistance to dorsiflexion and an isometric strength, as opposed to the (concentric) contractions produced by the often advocated calf raises.

Strength and stiffness of tendons and connective tissue. If we recall the findings of Leskinen et al (2009) from the discussion in chapters 4 and 5 they found that one reason international level 1500m runners exhibited superior running technique to their national level counterparts was an ability to better maintain knee stiffness during the contact phase of running. They speculated that this was due to higher levels of tendon and muscular strength around the knee joint. This would mean stronger hamstrings, quadriceps and calves and the tendons and connective tissues that attach those muscles to the bones. Saunders et al, (2005) in their review of the literature about running economy found studies that reported similar findings.

Folland and Williams (2007) confirm the ability of strength training to cause adaptations in muscle size, tendon structures and connective tissue. They also provide some reasoning as to why it is important to performance that can be related back to running, their contention being that increased tendon stiffness (and size) reduces the delay in muscle activation but also increases the amount of force able to be applied. This indicates that in addition to a muscle being stronger it is also likely to be in a pre-tensioned and elastic state, able to absorb and generate energy much faster than a slack, untrained muscle and connective structure.

I’m not trying to imply that less talented runners are going to be able to run a four minute mile simply by getting in the gym and doing exercises designed to strengthen your muscles and tendons. The point is that this is something that you can work on that has been shown to have a demonstrable benefit to running technique and running economy. Perhaps rather than running an extra 10km of slow running (or junk miles as people call them) you might be better served by fitting in another strength training session.

Where strength and coordination helps most in running technique. This chapter is one of the more important ones in this book. What I’ve explained is the importance of not just getting stronger, but your body learning to use its assets in the most efficient and effective way possible. Therefore what I have argued is that coordination is equally if not more important than absolute strength - especially for such a complicated activity as running. It would be much easier for us if we were trying to become champion power lifters where a limited number of muscles could be trained in a relatively simple way. As runners we need to be strong, but we need to be strong on coordination even more. Strength training is the easiest and most effective way to work on both aspects of strength simultaneously.

One of the key benefits I have found in working in the gym has been practicing using muscles that were either completely ignored or not strong enough to be engaged under my old running technique. What has developed is a learning and experimentation cycle where, as I have implemented changes in my running technique, I have been able to strengthen and gain awareness of the muscles needed during strength sessions. This continues to make those changes in posture and movement patterns easier to adopt.

For example, I want to run with more flexed hips and knees so I work on those specific postures and movements when I’m in the gym. It’s not about heavy weights at this stage of my development - always about coordination of movement by activating the right muscles at the right time. When things work in the gym or during a run I am able to try them out on my next easy run or gym session (I never experiment first up with speed). Over time the two sources of learning and experimentation have meshed together and now there is a very close alignment between my running technique and the exercises I am working on in and out of the gym.

Summary. The point of this chapter was to mount a sound argument for including strength and coordination training into your regular training regime - especially if you are seeking to improve your running technique. Hopefully I’ve started to convince you to begin thinking about running as a strength and coordination skill that can be learned and trained for. My philosophy is that the longer and better you can execute the skill, i.e. good technique, the faster you will be able to run. Having excellent strength and coordination will help enable you to do this.

****