It’s no easy task to shift from a running technique that has many problems to one that is technically sound. However, small steps in the right direction will yield more enjoyable runs, less risk of injury and even surprisingly large improvements in performance. Once you get a taste of these improvements you'll feel extremely motivated to continue to advance.

It is worth getting your running gait analyzed in the first instance. The evolution of your technique should then be benchmarked relatively frequently - if possible every four to six weeks. If you train with a group or coach you can ask them to watch for any back-sliding as you train. These steps will allow you and others to see results before the technical changes deliver a stunning new personal record. It also helps you to continually refine the changes you have made by absorbing the visual feedback of observing your running technique. These check-up videos provide a great audit trail of where your technique started and where it’s going today.

In this chapter I discuss various strategies for either learning to run as a beginner or refining your technique for more experienced and advanced athletes. I have divided the stages of running expertise into three phases: (1) Developing correct muscle activation, (2) Increase strength and stability through the hips, and (3) Fine tuning for power and speed. You’ll probably pick up bits and pieces from each stage as you progress. Nevertheless this allows you to break down the problem into manageable chunks and focus on different areas as your knowledge and technique improves. Learning from each phase will carry over into the next without much conscious effort. This is similar to running where we work on different aspects such as speed and endurance at varying times in our schedule; later as we’re focusing on training other attributes or racing these foundations can be easily maintained.

It might sound strange but the major objective for this chapter is to learn how to learn your running technique. Successful technique improvements can be made by gaining an awareness of how your body responds to various mental cues in relation to physical movement and the environment. Everyone’s wiring is slightly different, your neurological pathways have been fixed for decades and now you need to reprogram your brain to send different messages to your muscles.

As a final complication each of us absorbs information and learns differently, so one set of instruction that works for me might not work equally well for you. For this reason this chapter contains a number of physical exercises and mental strategies that allow you to practice getting a feel for how better running works inside your mind using your body. In chapter 4 and chapter 5 I explained in detail what running looks like and which muscles drive that movement pattern. We now come to implement what we learned by recognizing what good running feels like and how to stimulate your mind and body to create these more effective movement patterns.

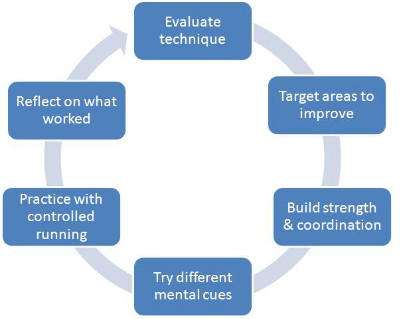

I was fortunate to spend the last two and a half years working in the online learning department at a good sized University. While I don’t make any claims about being an expert in learning and teaching theory, I was lucky to work with some clever people who could make that claim - although modesty prevents them from doing so! I was directed to an educational theorist David Kolb whose experiential learning cycle (Kolb, 1984) lends itself perfectly to teaching and learning a physical skill such as running.

What you will have noticed throughout this book

and especially in this chapter is an emphasis on:

- reading, absorbing and thinking about ideas and theories;

- observing these concepts through photographs, diagrams and

video;

- reflecting on what you see in these visual examples;

- trying out movement and thinking patterns;

- reflecting on how moving differently feels;

- practicing new skills in the gym and on the road; and

- training for running in a way that is sympathetic to implementing

your learning (chapter 11).

My approach is similar to Kolb’s idea that people learn best by watching, thinking, doing and feeling in a series of interactions and that this process is cyclical and evolutionary. This is important because it reinforces that learning to run with good technique is not a single stage process. You will need to evolve your running technique and condition your body in a series of stages with continual reflection on what you are doing so you can master running as a consciously competent skill.

This means that if you progress through the material in a linear fashion, it’s likely you will need to circle around and come at some of the concepts again. It's best to do this with the benefit of having tried things out with varying levels of success and failure. This is completely normal, most things only make sense after we have tried and failed a few times. The important thing is to keep trying and proceed cautiously when adding running volume and intensity. Also take care when learning new strength and coordination exercises and running drills. Taking things slowly means the consequences of any mistakes are greatly reduced. A day or two missed with a little bit of soreness from getting something wrong is preferable to months on the sidelines nursing a stress fracture.

If you haven’t already done so, begin keeping a diary of your progress as you learn. Instead of just recording how far and fast you ran, also reflect on how well you ran, what worked and didn’t work with your technique. As a competent runner who is conscious of what’s working and why, you’ll be more consistent, suffer fewer injuries and have the ability to refine your skills overtime. In racing there will be fewer bad days as you’ll always know how to extract a high level of performance from your body. How often have you heard runners talk about why they didn’t know what happened out there or it just wasn’t my day? I think this could be due to minor variations in technique and perhaps with greater awareness these bad days could be minimized. Eventually you’ll be able to cease this deeper level of thinking and analysis and just enjoy running with your improved technique. At this point you will be unconsciously competent. This is the goal, but you should have an understanding of how running works so you can identify problems as they emerge and continue to improve.

Before we begin. You no doubt have a few questions before we get into the process of learning to improve your running technique. I’ll answer these as best I can with the qualification that the answers will depend on the individual. Some people are more adept at learning physical skills, others a little slower; either way I believe everyone can improve their running technique.

When should you make a change? This is a question that is likely to be answered by your personal circumstances; however there are definitely good and bad times to try and make a change in your technique. Runners tend to be an obsessive personality type, we love the training and some of us are competitive animals that thrive on the cut and thrust of racing. Therefore, most runners will only contemplate improving their technique when they hit rock-bottom, get injured and can’t find a way out of their predicament with the usual treatment options.

But why wait? If the warning signs of injury are there and you’ve completed a gait analysis that indicates you have problems, then you should consider taking a break from hard training and competition to make the necessary adjustments to your technique. This might be difficult if you’ve got the pressure of scheduled competition. If this is the case, you should ask yourself whether it is worth getting injured and then needing an extended break from running.

Having said that, if you can finish your season at a lesser intensity in racing and training then you may feel more comfortable attacking technical improvements in the off-season. But speak to your coach or team manager about backing things off. If they have your interests on the same level to that of their club or squad they should understand how quickly a runner can transition from being sore to injured.

In some ways it’s easier to make changes if you’re already injured, that is certainly where I was at. I could jog, uncomfortably, but I could still move so I was able to start improving my technique as soon as the acute phase of the injury was over. I was still sore and the way that I was running was aggravating the injury site. This did reinforce the need to change and as my technique improved my little jogs did not irritate the injury anymore and I knew I was on the right track.

How long does it take? You should allow a minimum of 14 – 24 weeks to make your technique improvements stick. Do not compete in any races for at least 14 weeks. You don’t want to jump into competition until you have you technique programmed into your brain and wired into your neuromuscular system. The temptation to cheat and revert to your old problematic style will be too great if you jump in early. Allowing 14 weeks before your first test race (and I would say this is a controlled hard effort, but not all out) is a good way to approach it. I ran my first 5km PR/PB after this period of time. I allowed 6-7 weeks of jogging 4-5 days per week and had then completed a block of 7 weeks training which included building up some faster reps, tempo runs and long runs. With hindsight I would have waited longer. The more patient you are, the more tempo running and quality training you can nail without the pressure of racing.

When can I start running? If you are not acutely injured it is logical to run as you improve your technique. When I say some running I mean 15 - 30 minute jogs, it may even be easier to start with 1 minute jogs and 1 minute walks. You can then build this by adding to the jog e.g. 2,3,4,5 min jogs with 1 min walk until you can jog easily with your technical improvements in place for 15-20 minutes. If you’ve been doing big mileage or intense running you will need to ease right back if you start tweaking your technique. You’ll also find that altering the way you run uses muscles that have been long neglected. Therefore you may tire quicker than before and get sore in unfamiliar places. It's a good idea not to extend your jogs beyond the point where maintaining the technique becomes too difficult; either through loss of concentration or muscular fatigue. You need to slowly get fit using your improved technical pattern of running - this will take a little time.

Continuing to jog through the change and

learning process is helpful on a number of levels:

- it allows you to commence practicing and experimenting with new

movement patterns;

- it enhances the learning from the perception exercises in this

chapter;

- you can enjoy feeling the benefit of your strength and

coordination exercises;

- avoiding harder running sessions will help you build up strength

faster;

- running well is the ultimate goal, so practicing it brings

together all the components of your strength training, perception

exercises and the theory; and

- running will allow you to maintain a reasonable level of fitness

through the transition phase from your old technique to the

improved version.

How often should I race in the first season? Be cautious about over racing or jumping into a long run such as a half or full marathon too soon after making changes to your technique. It is your body and your love of running, so don’t be tempted to accept the pressure of your coach or running club to race too often after you’ve made changes. While you might be persuaded to make up the numbers for the team, you need to ask yourself whether your coach would sacrifice the body of a more gifted runner if they were coming back from an injury. Just because you’re a slower runner doesn’t mean running means less to you than the guy or girl who is headed to state or national titles. It’s important not to forget this.

Instead of racing a full season, use a small number of races or fun runs as test efforts of your technique and fitness, don’t try and race all out and definitely not too often. If you’re anything like me you would find that just running a race at 70% is a difficult thing to do - once you’re on the start line and the competitive juices start flowing, are you really able to hold yourself back? For this reason avoiding racing for a while is a good idea.

Three races within a month or two might be enough for a season. If you’re a distance runner choose 3km, 5km and 10km races to test your fitness at different distances. Don’t be tempted to overdo your pet race. Break it up a little and see how your improved technique stacks up against your old performances over different distances.

Finally, let your training and level of comfort in your improved technique drive when you should race. Only race once you have completed a solid phase (6 – 8 weeks) of tempo running and some mile race pace repetitions. If you feel consistently in control of your running mechanics then it could be time for a low key race or time trial to test how far your running technique has progressed.

Phase 1 - Developing correct muscle activation patterns. This section takes running and movement back to first principles. It is particularly relevant for new runners or athletes who have concluded from their gait analysis that they are not driving their running with the correct muscle activation pattern. If your technique is less problematic you may be able to skip ahead or use this phase as primarily a strength building exercise. Way back in Chapter 3 I discussed that if you have never tried strength training then that should be your first step in improving running technique. Strength training (the right way) helps improve muscle activation patterns and enable you to run with better technique for longer.

Phase I will help you adopt the building blocks of a good running technique through teaching you to activate the hamstrings and glutes as the primary force in driving your running. You may need to alter the way you have been moving for many years, perhaps even a lifetime. For this reason I have included a number of what might seem on first examination quirky thinking, observational and physical experimental exercises. These will help get you moving using different muscle combinations and patterns. You need to get the feeling for and understand that your body can move with very different combinations of muscles doing the work. This is also true of walking or even the way you stand, sit or do any physical task at work. We’re getting into the province of occupational therapists so I won’t stray too far into that, but the concepts are similar.

Improving the way you move. You’ll be learning and defining your technique as you go, but it will be one that is built on common foundations to that used by better runners. Experimenting with different postures, mental cues and movement patterns will help you get the feel for what is working or not. Do this on your short training jogs, using the exercises suggested here and when working out in the gym. After reading this chapter and experimenting with your own training consider devising your own mental cues and be able to describe what good running feels like inside your mind and body.

Training diary. I recommend keeping a

training and technique diary so you can note any realizations and

progress as you train both in the gym and on the trails and roads.

Grab hold of what works and write it down, it may be you’ve hit on

the mental trigger that works to prompt the correct movement and

muscular activation pattern in your body. Everyone can adopt a

better technique, but diverse mental cues are going to be needed in

each person to provoke the right physical response from the

body:

- Record your practice and perceptions.

- Record observations about how well you move on each run.

- Take notes as you observe better runners.

- Build your own mental cues that will work to drive correct

running technique for you.

- Record any sore or tight spots that develop and potential

causes.

Practice what you want to do in your mind. Sports psychologists have long espoused the benefit of visualization in athletic performance. They may have been focused on the psychological factors contributing to elite performance, but there is evidence that suggests if you practice thinking about certain movements, then strength gains can result. In running this means if you can visualize and practice optimal technique in your mind, you stand a good chance of realizing some benefits when it comes to physical execution. I’m not sure that imagining running 100 miles a week will get you ready for the marathon, so let’s not push things too far, but the concept is worth thinking about.

Strength and coordination exercises. Priority should be given to strength and coordination exercises that focus on activation, awareness, coordination and strength in the muscle groups needed to drive the fundamentals of good technique. This is mainly the buttocks (glutes) and hamstrings - remember this diagram? These exercises are all about stimulating and strengthening this muscle activation pattern.

The combination of perception exercises, gym

training and test jogging means that you are coming at the problem

from three different perspectives and give yourself the earliest

possible opportunity to begin making improvements in your running

technique. Here are four exercises described in the next chapter

that you can integrate into your program:

- Single and double leg bridging

- Dynamic single leg bridging

- Prone hip extensions

- Clam

For more information please visit the online resources or my coaching practice.

Shoe choices. It’s wise not to transition too quickly into ultra flat shoes or barefoot running. If you are accustomed to wearing a cushioned shoe do not throw these away just yet. You may consider the purchase of a pair of marathon racing shoes (some cushion, but much lighter) to wear on some of your test jogs. Also consider one of the Nike Free models for a small amount of running and for use in the gym.

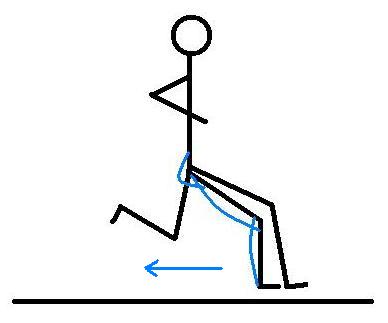

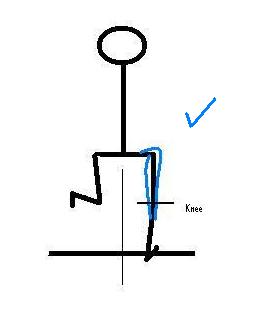

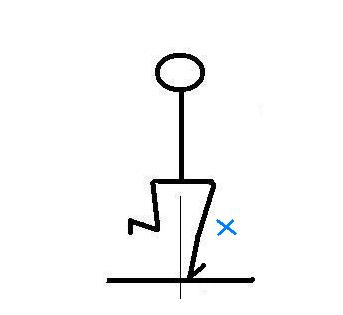

A few words on foot contact posture. As I explained in chapter 4 and chapter 5, for the foot to strike the ground in an optimal position relative to your body mass, work must begin in the preparation phase. Remember, it is more important to make sure the hamstrings and glutes are activated before ground contact than obsessing about whether you slightly contact heel or forefoot first. Setting aside extreme heel-toe or forefoot running that should be corrected; this can usually be set aside for later fine tuning. I definitely don’t want the large number of heel striking runners to feel discouraged by the deluge of forefoot and mid-foot commentary. There are many very good runners (even Olympians) who kiss the ground lightly with their heel first. The difference between this and exaggerated heel-toe action is that better runners have begun to initiate hip extension prior to touching down, therefore they are landing with their foot under the knee and the leg and hips have fully engaged, stable, strong muscles. You might recall this diagram from chapter 5 - correct muscle activation first, and then work on foot and ankle posture later.

Ultimately if you get the movement patterns right from the bigger muscles around your hips and the hamstrings your foot contact posture will begin to evolve without too much conscious effort.

Why you should never try and run on your toes. If you’re anything like me, you might be tempted to experiment with running up on your toes and not allow your heel to settle of the ground. With some popular running books espousing such a forefoot dominant foot plant and maintaining that posture until the foot leaves the ground (i.e. the heel never touches the ground), it may be a powerful temptation to go there. While some elite runners often look like they’re up on their toes in real time, the reality in slow motion is very different. The majority that I have studied land with a neutral foot, the foot is relatively flat and lands horizontal to the ground - the toes are not pointing down, nor are they pointing up in the best runners. These runners tend towards forefoot orientation, but even they still touch the ground with the heel during contact with the ground. The reasons why landing neutral is preferable are numerous; equally, the reasons why you should not try and stay up on your forefoot and toes are compelling - I’ll explain a few here:

Shock absorption and energy return. Neutral and forefoot oriented runners that let their heel to settle on the ground allow the foot and arch to flatten naturally and then stiffen as the foot leaves the ground. This transition is very fast but it means the foot can absorb and load energy as it flattens and then transfer the force of the hamstrings, glutes and calves as it stiffens (plantaflexes). If you remained on your toes this energy loading process would be incomplete and compromised.

Stability. A neutral foot is a stable foot - try and do squats in the gym while standing on your toes - actually, don’t because you’ll probably fall over and injure yourself. Balancing on your tippy toes is hard; balancing on a foot fully on the ground is easy.

A neutral foot can apply much more force. A neutral foot does not twist and apply vicious twisting to the foot, ankle, and deep compartment of the lower calves or shins - landing and remaining on your toes also forces the muscles in your foot and lower legs to work harder at absorbing shock than they are designed to do. Toey runners might tend to suffer from planta fasciitis, sore calves, Achilles problems and shin splints. Not to mention being unstable at the hips because of the smaller platform (toes/forefoot) available to absorb energy and apply force.

As a footnote I (of course) experimented with the toey landing and support posture - it landed me with a number of weeks off running with a nasty case of sore shins. The muscles in my lower calves: the soleus and tibialis posterior - were stressed out by this technical flaw within weeks of trying it out, so be warned. Running more neutrally at the foot has my shins and calves back to a buttery consistency, whereas they were old rope last year.

Perception and muscular awareness exercises. These exercises are designed to give you a feel for how movement can be driven by different muscle activation patterns. Try these out as your schedule allows. Some of them can be done in the gym, others just as easily at home. You should attempt these exercises in the first one or two weeks of beginning to improve your technique. You might only need to do them once or twice to get a feel for activating different groups of muscles.

To help find and activate your running muscles it is useful to develop a pre-running muscular activation routine that forms part of your warm up. Try a few hip extension exercises such as mini body weight squats to get your glutes activated and ready to run. This doesn’t need to be a full gym work-out; even doing ten gentle repetitions of an exercise can get the right muscles firing.

Elliptical trainer/strider experiment and practice. The elliptical trainer or strider is a popular piece of cardiovascular equipment that can be found in many gyms. For those of you who haven’t used one, it’s sort of like a blend of cross country skiing and running. It’s close enough to running that we can play around with and practice different movement patterns without falling over or risking injury. If you have the choice, a strider that operates horizontally is better than one that mimics stair climbing. This is a good place to build awareness of which muscles you need to get working to improve your running technique.

Purpose:

- Experiment

with initiating movement with different muscle groups.

- Demonstrate it is possible to drive forward movement with the

quadriceps and hip flexors or the hamstrings and glutes.

- Practice running with your knees more flexed than you’re used

to.

- Practice using a hamstring/glute dominant propulsion method.

How to: Get the gym instructor to give you a basic introduction to the machine so you can operate the resistance levels. Usually there’s a quick-start function that will get you going. Set the resistance at a low level, so it’s easy to generate movement without too much effort.

1. Start striding on the machine at a steady pace – think about which muscles you are using. Are they at the front or back of your legs?

2. Now consciously begin to drive the machine forwards with your quadriceps (the muscles at the front of your thighs). Does this feel any different or is it the same pattern for you?

3. Stop the machine for a moment and think about driving the strider with your hamstrings and glutes. This will involve pushing back with your legs and butt. Try to push back with each stride and relax your quadriceps as your leg transitions from behind your body to in front. Does this feel the same? Is this different to how you normally run or use this machine?

The feeling of thrusting forwards with your quadriceps and hip flexors is very different to pushing back with your hamstrings and glutes. Both patterns can drive the strider forward and both movement patterns can dominate running. The one you need to work on in running is definitely the ability to push back with your hamstrings and glutes.

Reflection: Was it possible to drive the strider using different muscles as the initiators of movement? How did that feel? Was it easy or hard to do? When you’re in the gym, would it be useful to use the strider to gently warm-up before your weights session so you can practice activating your hamstrings and glutes in running?

Stair climbing. Climbing stairs is something most of us are familiar with and just like running, there are different ways you can climb a flight of stairs. Later, if you take them two at a time it can be a great strength and coordination exercise, but for now single steps are fine.

Purpose:

- To feel the

difference between lifting yourself up stairs and pushing yourself

upstairs.

- Practice using the hamstrings and glutes to push your torso ahead

of the hips.

How to: The idea is to experiment with different muscle movement patterns. There are basically two ways to climb stairs. The first is to lift your legs one after the other up the stairs - the legs lead the body. The second is to propel yourself up the stairs - the body stays ahead of the propelling leg and hip.

1. Walk up a single flight of stairs the way you normally would – think about which muscles you are using and how you initiated the movement. Are you a lifter or a pusher?

2. Try lifting your legs up the stairs; this will involve lifting up your knees.

3. Try pushing or propelling yourself. Start with a flexed knee and hip and push down into the step, keeping your butt engaged so the leverage created by your hamstrings and glutes pops your body up to the next step. How much different did that feel to lifting?

Reflection: I was practicing this the other day and pushing yourself up the stairs is actually quite difficult, it takes a fair bit of strength to be able to do it. Similarly, running with this type of movement pattern also requires strength - yet another good reason to train for strength. How did that feel? Was it easy or hard to do? Store this away for later but the ability to leverage your torso forward by locking in your butt muscles is critical to mastering running.

Walking as you want to run. It may sound crazy but you can actually practice turning on different muscles as you walk. Try it out from time to time when you want to get a feel for moving with different muscles or in a different posture.

Purpose:

- To practice using the muscles you need to

activate in running.

- To allow you to feel what this is like in a low intensity, low

risk movement.

How to: If you walk as many

people do you probably tend to swing your legs in front of you,

land on your heel, roll over your foot and keep going. When I

described to people that once I started changing my running

technique I also changed my walking technique they were a bit

skeptical. However, you can use walking to experiment with

different muscle activation and movement patterns:

1. First set-up your posture for running - except you’ll be walking

not running. Flex your knees and stick your butt out a little more

than normal.

2. Imagine you are sitting on a railing positioned just below your

butt - don't let it drop down too far toward the ground. Keep your

back straight.

3. Try walking by pushing down and back - keep your thighs

relaxed.

4. Think about pushing back and pushing off.

5. Try to activate your hamstrings and glutes before and as your

foot contacts the ground.

6. Experiment with flexing your butt before and as you contact the

ground.

7. Keep your knees and hips flexed the whole time - don’t let them

fully straighten.

Reflection: What I have basically described is a pattern for running, but implemented more slowly in walking. You can practice this during the day as you go about your business. Try it out, think about it and then see if you can implement the learning on your next test jog. Note: this is easier to do using flat comfortable shoes - if you’re in your dress shoes for work, maybe hold off until you get home.

Little hill strides. In chapter 11 I discuss the benefit of many traditional types of running training and how they might be modified or adapted to the athlete looking to making changes to their technique. Running hills is one such type of training that can be very helpful. In the early stages I don’t suggest running 6 x 400m up a tough hill; here we are talking about very short modest paced efforts of 30 - 80m or less on a reasonable but not steep hill.

Purpose: Doing some controlled hill strides can help you fully activate your glutes and hamstrings. When you run hills your foot contacts the ground slightly earlier and therefore you are forced to begin activating your buttocks and hamstrings early in the stride. Make sure you push up the hill using your buttocks and keep pulling with the hamstrings to complete each stride. Make sure the hill is not to steep as you need to be very strong to run with good technique up a hill. Avoid pulling out of each stride early or lifting the legs up the hill with your quads too much.

How to:

1. First set-up

your posture for running - flexed knees and hips.

2. Ease into the stride making sure you are pushing yourself up the

hill by thrusting. Remember, push and pull yourself up the hill not

lift.

3. Do the stride at about 60-70%, a little intent but not fast -

think about being strong and complete in your stride rather than

trying to run too quickly.

4. Keep your knees flexed and try to feel springy as you run up the

hill.

5. Do three or four strides to get the feel for it.

6. Walk down the hill rather than run to save your legs

7. Think about exaggerating the flex in your knees. Try and keep

your back reasonably straight.

Reflection: This exercise shouldn’t leave you physically exhausted, if it has, you’ve made the hill too long or you’re running too fast. Did you manage to bounce up the hill pretty easily? Did you stop yourself from reaching or lifting forward with your legs too much? Can you bring what you learned into your next test jog?

Exaggeration perception exercises. These exercises are designed to trick the body into adopting a new movement pattern by exaggerating the effect you are trying to achieve. When I perform this type of exercise I often think I’m exaggerating an aspect of my running technique, but I am actually causing a movement pattern that is normal in the context of the ideal running technique.

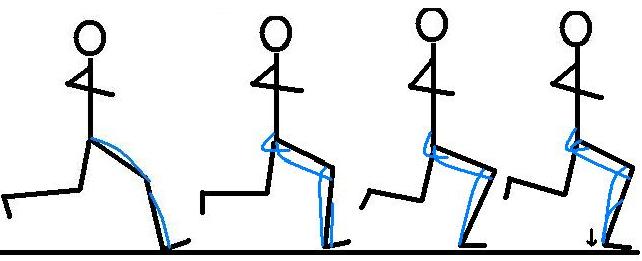

Bum kicks. Bum kicks are a popular running drill that can help stimulate technical improvements if done correctly.

Purpose: The purpose of this exercise is to practice activating fast knee flexion and hip extension from an optimal running posture by emphasizing early and powerful activation of the glutes and hamstrings. In essence, this drill describes sprinting technique as they tend to run powerfully from a deeper flexed posture at the hips and knees.

How to:

1. Adopt a

comfortable posture - knees and hips flexed, upright back.

2. Jog some easy efforts of 30-50 meters.

3. Try and pick up your heels very early so that your heel reaches

under your butt before the thigh travels too far behind your

body.

4. Keep your butt engaged as you activate your hamstrings.

5. Ensure your butt on the support leg stays engaged.

6. Don’t do this exercise too far onto your toes - try and land

with a neutral foot.

7. Emphasis is on lifting rather than generating lots of

thrust.

Physical interventions to help proprioception. Sometimes it’s too difficult to think your way through a problem without a physical intervention or aid. One such method that I experimented with was taping my knees into a slightly flexed position when I was trying to change my technique after the injury behind my knee. When I was out jogging I would always feel pain if I slid back into my old method of letting my knees fully extend and then contact the ground. Early in this phase I had a physiotherapist tape my knees so they could not be fully extended, there were in effect physically fixed and prevented from fully straightening.

A word of caution - don’t try this at home. You want someone who knows what they are doing when taping up a joint, especially the knee. I scheduled the visit to the physiotherapist so I could go on a test jog straight after the consultation. I only did this twice but it was a real eye-opener in terms of just how much I was still trying to straighten my legs even though I thought I was doing a good job of keeping them flexed. The trick was to try and keep the idea of flexed knees in my running once the tape was taken away. I’m sure I backslid from time to time, but in general it was probably a helpful thing to try.

Phase II - Increase strength and stability through the hips. The first phase of learning how to run was focused on generating the base movement pattern required for good running, using thrust from the hamstrings and buttocks to drive the body forward. This phase is designed to continue focusing on this movement pattern and the strength and coordination needed to get more stability, bounce and free energy out of each stride. If your initial gait analysis was reasonable, then this is the place to start. This section covers some ideas for how you can begin to stimulate improvements in this aspect of your running technique.

Early activation of hip extension in the preparation phase of running adds to the strength and power of your running and increases the inherent stability of your hips. All the key muscles (glutes, hamstrings and calves) are activated before and during ground contact. Therefore, early activation of these muscles can help solve many problems related to instability at the hip by reducing twisting at the knee and any propensity to over-pronate at the foot ankle.

If you run along an extreme central line i.e. your feet contact the ground under the midline of your body, you may need to work harder to ensure that your thigh tracks directly under your hips. During gait analysis this will be relatively easy to identify. This problem is caused by the glutes (maximus and medius) not engaging early or strongly enough to maintain optimal posture and align the thigh and foot under the hip.

Feet and thigh under the hips, not the centre of the body. Many runners tend to follow a central line. They could easily run along a straight line with both feet contacting the line with each stride - much like a catwalk model. The implications of this are the thigh is angled towards the middle of the body with the hips popping out and dropping which creates instability and reduces power. The body falls off the hip or the hip collapses; this is a weak position as force is directed sideways rather than to the rear which maximizes forward thrust.

In addition to the loss of thrust, there is growing research that links hip weakness to injuries to the knees and lower limbs. A large proportion of runners have wonky hips which goes a long way to explaining the cause of many overuse injuries through the knees, shins, ankles and feet. Any lateral deviation through the hips can and does cause injury by causing excessive twisting and movement in the lower parts of the bone, joint, tendon and muscle chain. Researchers, Kawamoto et al, (2002) measured the torsion (twisting) imparted on the tibia (shin bone) during running.

They found that runners exhibiting high levels of torsion through the shin had a hip and leg profile that had the foot landing on a central line. This evidence suggests that runners with this technical weakness are more likely to suffer from stress fractures in the tibia and the insidious medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) or shin splints. I suspect that this pattern may also contribute to other overuse injuries around the hip, pelvis and groin.

Strength and coordination exercises. Priority should be given to strength and coordination exercises that continue to build strength, power and control around the hips and hamstrings. The phase one exercises can be used during your second gym session of the week and these new phase two exercises can be adopted and learned in the first. The reasoning for this is you will have begun to master the coordination of the first set of exercises and they can now be used to focus on building strength. These new phase II exercises should be added with the primary motivation being to build coordination first and strength later.

These exercises all focus on activating,

building awareness, coordination and strength in the muscle groups

needed to fire the hamstrings and glutes quickly (drives early hip

extension) and to promote stability about the hips (position thigh

and foot under the hips). Here are three exercises described in the

next chapter that you can integrate into this phase of your

program:

- Barbell squats

- Decline single leg squats

- Monster walking

For more information please visit the online resources.

Shoe choices. In this phase you could progress to wearing lighter trainers or marathon racing shoes for most of your running - you may have also begun logging a few miles in a shoe similar to the Nike Free. In this phase consider looking at a pair of Nike Free 3.0 for some test jogs. Don't progress to longer runs or harder sessions in these flatter shoes until you are confident and comfortable with your technique and have done a number of easy jogs without any pain. If you feel discomfort don’t push it, put the flatter shoes back in the closet until you’re ready for them.

Perception exercises. These exercises are designed to emphasise activating the glutes in good coordination with the hamstrings during the preparation phase of running to promote a more stable position of the leg and foot underneath the hips.

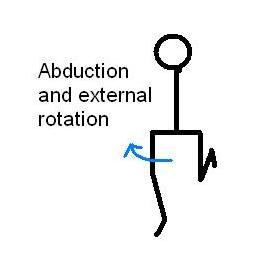

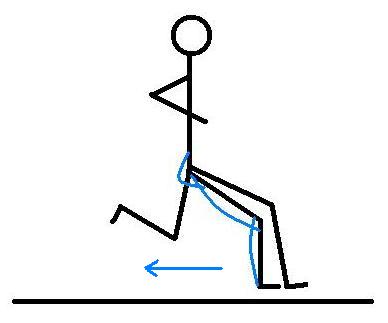

Gunslinger running (stable through the hips). Learn to run with your legs and feet under your hips. This exercise also activates very important stabilising influences in running, your buttocks (glute maximus and medius) and your vastus medialis (medial quad). The main purpose of this exercise is to activate the glutes so that they prevent the thigh bone from tracking towards the midline of your body. In addition to extending the hip the glute maximus also plays a role (with glute medius) in abducting (taking the thigh away from the middle of the body) and externally rotating the hip. You see many photographs of elite runners taken front-on where the thigh appears almost splayed outwards when they are in contact with the ground. This posture has the thigh both slightly externally rotated and abducted, meaning that the glutes are playing their role to perfection in directing the force of the stride behind, not to the side of the runner.

How to:

1. Start out with

your feet held wider under your hips than you are used to, keep

your knees and hips flexed and wider apart than you would normally

run. Note: if you already run with your legs and feet under the

hips you can skip this exercise.

2. If you bounce up and down a bit on your buttocks the posture

should feel stable and springy. In this position, you could easily

be a gunslinger walking into a wild west town jangling your spurs a

little!

3. Run a few easy strides and try to keeping your legs under the

hips as in the picture below for an easy short jog.

4. Try firing the glutes before your leg straightens ahead of the

body - keep your knees flexed.

5. The idea is not to run with your thighs held wider than your

hips, but to trick your mind into activating the glutes and

tracking the thigh under the hip. If you’re habitually a central

line runner it’s likely you will feel like your legs are spread a

mile apart, but the reality is your thigh will most likely start to

track in its correct line under the hip.

6. This is a good experiment to undertake on a treadmill with a

video camera set-up behind you while running. Alternatively, a

friend can film you as you do an easy run at the track.

Reflection: Did you feel your buttocks activate more in this posture? Did it actually cause you to run with your thighs under your hips? Think about consciously activating your glutes during running - especially just prior to and early in ground contact. How similar is this feeling to activating your glutes when in the gym doing squats or leg press?

Fast through the hips. This is a thinking exercise that you can try out on a practice jog or doing a few easy strides. You want to try and experiment with different mental cues to stimulate your body to start activating hip extension before ground contact. Try these out and see what impact it has on your running. As your hip extension begins you might notice a perceptible difference in how hard you are impacting the ground i.e. you should feel much lighter and springier than before because of the reduction in braking forces and activation of muscles and tendons that better cushion and drive your stride. After you get the feel for this, try jogging on a harder surface to check how much lighter on your feet you feel and sound.

How to:

1. Try to flex

your knee and activate your buttocks simultaneously.

2. Fully drive through each stride by squeezing the butt and

keeping an upright posture.

3. If you’ve traditionally been slow at this, the only way to

stimulate a fast response is to think about doing it earlier than

it physically happens.

4. Think about a beat or rhythm to do this - pop from one leg to

the next.

5. Check your stride rate - this may increase your cadence a

little.

Reflection: Think about being

quite springy between strides. Being powerful with each stride

gives you more air time to get the hip extension happening before

your contact the ground:

- Did it increase your stride rate?

- Did you contact the ground less heavily?

- Did you feel more powerful in your stride?

- Were you more stable?

If you are struggling with this you may need to get stronger through the hips and hamstrings.

Sand running and sand dunes. It’s been well documented that legendary Australian middle distance runners John Landy and Herb Elliot were trained regularly by their coach Percy Cerutty on the sand dunes at Portsea near Melbourne. We can all imagine how hard it is to run up the steep face of a sand dune over and over and how fit this would make you. However, it’s more difficult to put your finger on what technical improvements this may bring to your running. I think there’s a good case to be made for including some sand and sand dune running into your training if you have the opportunity. This is definitely a time where going barefoot makes a lot of sense - shoes will fill quickly with sand and make the job harder, the surface is also forgiving so impact forces are negligible. Just be sure to check for hazards of modern life like syringes and broken glass.

Purpose: The purpose of running on sand and particularly running up some dunes is that it will force you to pick up your feet very quickly and early. This is a great way to stimulate and strength the hamstrings and work on early activation of your stride. A slow stride in the sand means you’ll quickly sink and find the experience sapping.

How to: Try to stay above the ground by flicking between each stride as quickly as possible - over emphasise lifting your feet with the hamstrings before you contact the sand. Use your glutes to stabilise and keep your thigh tracking under the hips. Don’t do too many repetitions – only as many as you can maintain good form and early activation of the hamstrings and glutes.

Reflection: How much easier was it to get up the dune with quick activation of the hamstrings and glutes? Did it also stimulate greater levels of forward thrust with the thigh (hip flexion)?

On your run. Think about the following mental cues and reminders before your test jogs to reinforce some of the concepts discussed in this chapter. These cues and imagery are the ones I use to help focus on my technique as I run. They may not work as well for you, but you could develop your own set of cues that make sense in your mind. Remember we are trying to mimic the technique discussed in chapter 4 and the muscular activation pattern discussed in chapter 5. We all have the same target, but what we think about to get there might be different.

Experiment with my cues to see if they work for you, if they don’t, try your own. Try not to confuse a mental cue with the physical reality of what is happening. Just because I picture in my mind doing something different, it may turn out to trigger a slightly different physical outcome. For example if I focus on pulling through and lifting my foot with my hamstrings I’m actually triggering early hip extension and engagement of my glutes. The message sent from the brain says lift, but the muscles respond with paw-back and strong early thrust.

Getting ready to run:

- Deliberately

flex my knees in an exaggerated way.

- Flex my hips slightly, this should happen almost automatically in

response to flexing the knees.

- Feeling some pull in my butt and hamstrings.

- Make sure my feet are under my hips.

- Straighten up my back.

- Do a few bouncy squats in the posture to activate the glutes and

hamstrings.

The first few steps:

- Take small

easy strides making sure I activate my hamstrings and butt. I’m

picking up my feet with my hamstrings and pulling the ground

towards me with the glutes.

- Deliberately try and keep my knees flexed - I do this by

activating the hamstrings and butt - the flexed knee and hip with a

straight back posture helps with this.

Easing in to the run:

- Pull the leg

back towards you in the preparation phase with the glutes from the

outside in.

- Try to activate the very tops of my hamstrings picking up my legs

- it feels like this to me, but in reality picking up the

hamstrings just gets my hip extension going early and helps hasten

the transition from back swing to forward swing as the foot leaves

the ground.

- Try to bounce from one leg to the other - get the butt involved

to pop you ahead of your hips.

You don’t want to see a lot of your feet, if you take a peek down towards the ground if you are seeing a lot of your feet and shins it’s a sign that you’re over extending your knees and most likely that you’re not initiating your hip extension early enough. This is especially true on easy jogs where there is no need to fully straighten your legs ahead of your body.

Keep your head up and level, looking at the ground with your head stooped can lead you to lean forward at the waist, so keep your head up and back straight. Stay tall with a long spine.

Keep the glutes engaged through early contact this will give you more rebound, more push-off, more flight time that helps you have time to begin extending the opposite leg before ground contact. You want to feel fast, strong and springy from stride to stride. These can feel like bouncing from one side of your butt to the other.

Phase III - Fine tuning for power and speed. The third phase of learning how to run is focused on fine tuning what you have built during phases I and II or what you already had in your natural armory. This phase can be thought of as continuous improvement. By now your technique should be sound with proven ability (through gait analysis check-ups and running injury free) to activate your glutes and hamstrings to create a powerful, springy and stable stride. By this time if you’ve previously had deficiencies in your technique you may have run a personal best/record or two - if this is the case, congratulations, I’m genuinely excited for you, especially if you’re a mature runner like me, beating the times you posted as a teenager is extremely satisfying.

In this phase you should continue to build on the learning of phases I and II, however the focus will shift to developing the awareness, skill, strength and coordination needed to make your stride even more compact, efficient and powerful. The primary goal is to exactly coordinate the activation of the glutes and hamstrings as you learn to leverage your torso forward, over and ahead of your hips with each stride. I think this is as much about feel as it is about strength with minor changes in knee flex, hip flex and pelvic tilt needed to hit the mark.

During this phase your stride should begin to exhibit a much faster transition from back swing (hip extension) into forward swing (hip flexion). Also focus on the optimal positioning of the ankle and foot to maximize the transition of energy generated through the glutes and hamstrings to the ground. This is the phase where some barefoot running and/or running in relatively flat shoes and spikes will become most beneficial. Finally, you should examine and train for some technical cues for initiating surges during a race and developing a powerful finishing kick. These cues will need to be practiced in specific training sessions outlined below to simulate launching a rapid change of pace while running an even paced rhythm with race-like pressure and fatigue.

Strength and coordination exercises. Priority should be given to the following strength and coordination exercises to complement the test jogs and perception exercises suggested in this phase. As with the previous phase, gym exercises you have already mastered can progress from coordination to a strength focus with explosive elements. These new exercises should be added with the primary motivation being to build coordination first and strength later as your progress through phase III of this program.

These exercises all focus on activating

coordinating the glute and hamstring relationship to a very high

degree. Here are three exercises described in the next chapter that

you can integrate into this phase of your program:

- Dynamic single leg back extensions (body weight and

barbell)

- Leap onto platform

- Step-ups with barbell

Limit hip over-extension or slow leg recovery. The hamstrings do much of the work in running, but they can’t be effective without harnessing the power of the glutes. So there’s no surprise that better runners have well developed buttocks. The strength and power of the glutes needs to be worked on at the same time as that of the hamstrings. The reason is you want the glutes to activate in a highly coordinated way with the hamstrings. Powerful and technically exceptional long distance runners activate the glutes which capture the force generated by the hamstrings in order to lever the torso forwards ahead of the hip and then recover the leg quickly into the next stride. The strength training you do needs to account for this key moment in the running cycle.

Training with more explosive plyometric work. As you become more technically adept and your strength and fitness improves you should consider adding more explosive exercises and plyometric drills into your program. As with all strength and coordination training it's wise to start with easier exercises and then progress. In the realm of plyometric training you can begin with adding more bounce and explosive movements into your regular strength based exercises. As you progress you can include various hopping, leaping and jumping drills. Finally you might attempt some of these drills carrying a barbell and do more difficult exercises like depth jumps from high platforms. Caution: progress slowly and cautiously with this type of training.

Barefoot running and working towards a neutral foot posture. This stage of your development is the right time to add more unshod work into your training. Running in minimalist or no shoes does give you some good benefits: a feel for what is happening under your foot and for building up plantaflexor strength which is an important part of getting maximum bang for your buck out of the triple extension of hip, knee and ankle. The extra perception of how your foot is contacting the ground will help to fine tune your landing pattern to a neutral, more stable and powerful platform for running. A neutral foot is also much closer to being plantaflexed, which according to Bosch & Klomp (2005) provides a much more powerful and faster (shorter ground contact) stride as force is not lost through a floppy foot. The neutral foot is also able to flatten at the arch to absorb shock and return energy more effectively.

Landing with the foot flat allows dorsiflexion (flexed ankle) to occur at the ankle which pre-stretches and loads the deep lower calf muscles and the Achilles tendon with energy ready for powerful stiffening of the foot to occur (plantaflexion). This provides a stable, springy platform for the transference of forces from the buttocks and hamstrings and allows the foot to leave the ground with minimal energy expended. This loads the Achilles tendon and the foot full of energy - in a review of the literature by Saunders et al, (2004) evidence was presented that this as much as 35% (Achilles) and 17% (foot) energy return. So maximising foot placement is very important to improving at higher levels of performance. Finally, we learned in chapter 5 that the majority of the force of the stride is expended in the early part of the contact phase. This makes it absolutely critical to have the foot strong, stable and ready to plantaflex (stiffen) as rapidly as possible so these forces are not allowed to dissipate.

Changing gears: surging and finishing. If you’ve often wondered why it is that the best performers always seem to have an extra gear in hand when it comes to destroying the opposition in the final stages of a race then you’ll be interested to learn that the answer is likely to be in-part technique oriented. It would be easy to believe that these individuals with the ability to close 5000m and 10,000m races with withering speed are just gutsier or blessed with some innate gift that is impossible to understand. Certainly they are in possession of a very efficient and powerful running technique and probably a good distribution of fast twitch muscle fibres. The other reason why these kickers can close with such impetus is that for the duration of the race they have been running with a more efficient technique than their competitors.

Their technique also has the potential to expand from being tighter and more compact, and while it might appear shorter striding they are actually covering the same ground because of the greater power generated. When they open up the taps in the closing stages, their stride is able to lengthen further because they can exert more force when they switch on, this increases speed by elongating their stride at a similar stride rate. The competition is restricted because often they’ve been running with a less efficient stretched technique that does not allow them to lengthen.

Cues. The research suggested that as speed increased some measurable changes occur in the athlete, you need to become more the sprinter and less the long distance runner as you search for speed to close out a race. With awareness it is possible to practice learning these mental cues in training. So in concert with improving your technique you should also practice changing gears. The knees and hips flex a little more and there is less overall hip extension as the powerful, technically sound runner is able to assume a technique much more similar to a sprinter.

Training to surge: Practice this in your tempo runs 2- 3 times during a session. You’ll be running reasonably hard in these training sessions so the simulation of surging will be demanding and a realistic simulation of trying this in a race situation. This is another thing you can also practice in a low-key competition, one where you don’t race all out, but under control so you can try different technical elements and race strategies. Note: this type of training is for very fit runners.

Example surging sessions: based on your

prescribed tempo pace per Daniels’ Running Formula (2005). Session

example: 6km tempo run at the 2.8km mark instigates a 200m

surge:

- Flex forward at the knees.

- Drive harder with the glutes.

- Increase pace from tempo pace to repetition pace or interval pace

(slightly less aggressive).

- Feel your flight time increase but your cadence remain the

same.

- Stay relaxed and try to hold the same breathing pattern.

- Return to previous tempo pace holding good technique and

rhythm.

At my current fitness level this would involve dropping from 4 minute/km pace (48 second/200m) to a 40 second 200 meter surge, or following the less aggressive pace a 44 second 200m surge. You should try and trigger the pace change by a physical change in technique rather than just increasing your general effort levels. Your ability to recover from these surges is as important as being able to launch them. Practicing this in training is likely to give you an edge over less prepared competitors. Having a surge in your armory allows you to run more aggressively during a race and may give you a decisive break that is never made up by your rivals. It also allows you to respond more calmly if you are on the receiving end of such tactics - initiate your mental and physical cues, relax and let your pace increase. Of course you may need to ease back if the surge is too fast or too long for you to sustain, but at least you’ll have the option to go with competition.

Training to kick: Training to kick is

going to be a combination of pure speed work (done in isolation)

and a blend of tempo pace work with rep pace elements mixed in.

Similar to the surge training except that the change of pace will

always occur in between tempo efforts or at the end of a tempo

cruise interval. Session example: mile tempo cruise intervals with

reps:

- Complete the 1 mile cruise interval at your tempo pace.

- Jog / recover for 400m.

- Run 200m at rep pace.

- Recover for 200m.

- Run 400m at rep pace.

- Jog / recover 400m.

- Do next mile cruise interval.

The idea is to condition your body to move

between different paces and be able to run with good technique when

fatigued. Session example: 1000m tempo cruise intervals with

kick:

- Complete the first 800m of the cruise interval at your tempo

pace.

- Close the last 200m at rep pace or faster.

- Launch the closing speed with physical and mental cues.

- 1 - 2 minute recovery jogs between reps.

****