It’s difficult to convey the amount of thought I've devoted to my running footwear over the years. As a heavily marketed potential solution for prevention of running injuries and enhancer of running performance, how could I help getting sucked into the hype? I was constantly sore and injured, so I kept going back to the promised land of shoe technology. Unfortunately the answers to my problems were never forthcoming.

I currently run in four different shoe models from two manufacturers, but my wardrobe is filled with failed experiments that I never wear and that doesn’t include the pairs I’ve given away to charity, friends and family. The question I kept trying to answer as I purchased another pair was: will these shoes make a difference in terms of running comfort and injury prevention? Would they make me run better? For the most part the answer was no, there is no such shoe, no magic formula. You have no idea how much money answering that question has cost me.

In this chapter I discuss why I believe shoes (or more specifically your feet) are the last place you should look to solve your running technique or injury problems. However, I do believe that wearing minimalist shoes in terms of weight, bulk and interventionist technology will help you get the feel of making technical improvements to your running much quicker. As such, I’ll suggest shoe features (or lack of them) that could be useful for helping improve your technique. But remember, there is no silver bullet, only enablers to help you get closer to the solution.

Chapter objectives. The objectives of this

chapter are designed to demystify some of the hype around shoes,

barefoot running, foot type, running injuries and performance.

There is little doubt that there are good and bad shoes, but we’ll

see that shoes are less relevant in preventing injury or enhancing

performance than correcting flaws in running technique. This

chapter explains:

- Injuries, the root cause.

- Interventionist versus neutral footwear.

- Why firmer is better.

- The impact of high heels.

- Why a light shoe does not need to be a flat shoe.

- The case for wearing more than one shoe model.

- Why running barefoot is not a miracle cure either.

- A shoe buyer's guide: interview with an expert.

Injuries - the root cause. Researchers are beginning to find that most running injuries are not caused by problems associated with the shoe, foot or ankle. As I've indicated throughout this book, many problems that manifest in the lower limbs and the feet have their origin at the hips. But for years the obsession with pronation, flat feet, and high-arches has dominated discussion and shoe design. However, there is little evidence to support these concepts in the real world. For years I faithfully handed over a price premium for features that I didn't need. So why is it that we think that the shape of our foot should dictate the type of running shoes we need? Looking at the shape of your foot as a predictor of how you run is a nice selling point, but it makes no difference to the way you run. Forget about standing on wet concrete or walking on pressure plates to work out what sort of shoes you should buy - start thinking about the way you run as indicated by your gait analysis. You must consider your technique before buying unnecessary shoe feature.

If there are problems with your running technique there is no way a shoe or not wearing a shoe is going to solve them. Certain shoes can help make a technical transition easier, but expecting to run like a pro or avoid injury just because you buy a pair of shoes or throw away your shoes altogether is wishful thinking. Equally, if you have big pronation problems around the foot and ankle, the answer is not going to be a motion controlled shoe. I’m sorry but they don't help, I’ve tried everything, I’m the guy with a closet full of running shoes that weren’t the answer.

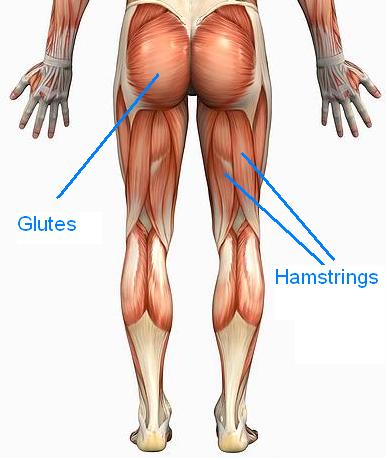

Look to the hips first. What is becoming clear from the research is that the likelihood of injury is mostly linked to problems originating at the hips: hip muscle (buttocks) weakness, poor coordination between the hamstrings and buttocks and posture. This therefore becomes a running technique, strength and coordination issue rather than a shoe design and feature problem.

Running with your feet on the midline of your body. Earlier we discussed running along a central line as a technical flaw. This is a major problem and one that has been shown to predispose an athlete to shin injury and stress fractures through twisting (torsion) of the tibia by placing the foot and ankle in a more pronated position. Pronation might manifest at the foot and ankle but the root cause is at the hips. If you stand on one leg with your foot under the midline of your body what happens? Your shin bone (tibia), feet and ankles start to compensate for the angle of your thigh at the hip. Kawamoto et al (2002) linked this running posture to increases in tibial stress and torsion and speculated that it was a likely contributing factor to development of shin splints, medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) and/or stress fractures. Given the additional twisting of the lower leg, ankle and foot it’s easy to see how running in such an unstable position could contribute to a range of other common injury problems suffered by runners.

Hip extensor, abductor and external rotator weakness. Without looking too hard, I’ve found numerous studies that point to the hips being the origin of many running injuries. Niemuth (2007) in his review of the literature found numerous examples of studies linking hip extensor (glutes and hamstrings) and external rotator/abductor (glute medius) weakness as a leading potential cause of lower limb injury in a range of athletic pursuits. He also provides a number of useful tests of hip strength and control. As a self test, try to perform a single leg squat. If your knee-cap (patella) dips inside the line of your big toe you may have a problem. Additionally, I would add that when performing single leg squats or other single leg exercises that if your hips are held forward and you feel as if your hip is popping out to the side, then weakness is evident. The hips should be held back and slightly externally rotated so that your hips remain flexed through any movement.

In chapter 4 and chapter 5 we discussed the importance of early activation of the hip extensor muscles (hamstrings and glutes) in the preparation phase of running. This brings the foot closer to the body and activates all the stabilization and power generation potential of the glutes, hamstrings, calves, achilles and foot. So the combination of forward impetus and stability keeps the hip strong and the foot aligned under the hip as the stride takes place. Running with your hips held flexed in preparation and the early part of contact helps activate the glutes and hamstrings in a more optimal way to enhance performance and stability.

Activating the gluteus maximus (pictured above) also helps to stabilise the hips, much more than people realize. Such a big muscle is not only there to provide main force: its actions, attachments and even the way it wraps from lower back and pelvis to connect to the femur (thigh bone), iliotibial band and ultimately the lower leg make it a very stabilising and powerful influence running and walking. If you’re not activating your hamstrings and glutes before you contact the ground, there is little chance your hips will be stable.

Interventionist versus neutral footwear. It’s very interesting that there is so little evidence contributing to a rational argument in support of wearing feature-rich footwear to counteract the effects of foot shape. Richards et al (2008) sought evidence in the scientific literature to support the notion that pronation control and highly cushioned shoes actually helped prevent injury. The problem was they didn’t find any.

Another recent study presents compelling evidence that selection of shoe features based on foot type makes no difference to injury rates. Knapik et al (2010) conducted a large controlled trial of 700 men and women undergoing Marine Corps training in the United States of America. Participants were prescribed running shoes on the basis of foot type. High arched individuals received heavily cushioned shoes on the basis that this foot type is supposed to be inflexible and needs more cushioning, moderate arched individuals were assigned a moderate stability shoe and flat footed recruits received a full feature motioned control shoe model. There was no difference in injury rates in this group compared to a control group of a similar number of recruits. So despite a prescribed shoe feature based on the foot type of the subjects in this study there was no difference in injury rate compared to the group that had no such prescription.

As a high arched runner I feel vindicated by this study, having been told I should be wearing cushioned shoes. I ignored the advice and have been wearing relatively minimalist neutral shoes for all my running over the past 18 months. Another study (Ryan et al 2010) provided evidence that prescribing motion controlled shoes to a group of women training for the half-marathon actually increased their running related pain and potentially risk of injury. It’s hard to find good reasons to wear heavy, stiff motion controlled shoes when there is little evidence to support their effectiveness and now new evidence suggesting they are not effective or might even contribute to injury risk.

Firmer is better. Cushioning in shoes needs to be firm. Spongy, soft trainers reduce your ability to feel the road and seduce you into landing more heavily than you might if you could feel the ground. Soft shoes give you that sinking feeling, rather than a clean fast foot strike that gets you quickly into the next stride. As my technique has evolved I find I can’t run in soft heavily cushioned shoes. The lack of perception of ground contact and precision in my foot-strike seems a major problem. I would caution against buying what feels like the cushiest shoe when you’re in the store - if you need some cushion look for material that is slightly firmer rather than a super spongy feel. If your body can sense what’s happening at ground contact, you have a much better chance of making technical adjustments that could improve your overall technique.

High heels. The evolution of shoes with bigger more cushioned heels seems to be based on the view that most runners heel strike and therefore need to protect their calves and achilles tendons from over stretch. But does the bigger heel actually make us lazy? If it weren’t there would we make more adjustments? Moreover, does the bigger heel actually force contact with the heel first when without it the foot might contact more neutrally and naturally? Does this interrupt the natural absorption and release of energy through the foot, calf and achilles complex?

The impact of this may well make us less efficient as runners, weaken those muscles and tendons by placing the foot in a soft plantaflexed position. By this I mean the foot is functionally plantaflexed, but not through the action of muscle and tendon strength - therefore this may weaken the plantaflexors. A recent study by Lieberman et al (2010) seems to support this notion that wearing cushioned running shoes does lead to changes in running mechanics. They compared the landing posture of the foot and ankle between runners that grew up without shoes compared to those who had worn traditional cushioned running shoes. The differences were stark, the barefoot runners landing much more forefoot/neutral and with less impact force than the habitual shoe wearers who landed hard on their heels.

Some shoes are designed such that from the outside they might appear to have a high heel but they may in fact have the heel sit down within a cup. If you desperately need some cushioning I’d look for a shoe that has the heel sitting down a bit so that your foot is held relatively flat in the shoe, even if there appears to be a heel-toe drop in the shoe’s cushioning from the outside.

Marathon racing shoes - a good transition point. The variance in shoe weights and cushioning available today is extreme. The good news is that you can get a light shoe (much better for practicing good technique) without having to sacrifice all cushioning and support. I’d love to be able to run in the flattest, lightest racing flats I could get my hands on. However, my technique can't take me there yet because I am in the process of neutralizing my foot and ankle posture from years of being a heel-toe runner. Happily there is a middle ground that will help you run with better feel for the road and encourage a more neutral posture at the foot and ankle.

These shoes are the marathon racing shoes and they’re great - especially for lower mileage average runners, you can train and race in them without sacrificing support and a little cushioning. Most shoe manufacturers have a few models in this class; they have good forefoot protection and a small amount of heel cushion (more than a true racing flat) without it being a massive imposition on your running. The good news is that these shoes are almost half the weight of highly cushioned shoes. Even if you have your heart set on being a natural runner, please consider these types of shoes as a transition step. Give your body a chance to adapt before you start belting out 400m repetitions barefoot.

I strongly believe in moving away from controlled, bulky, highly cushioned and heavy shoes. If you are in the process of adopting a better technique as described in this book, then a lighter, less cushioned, more responsive pair of shoes is going to help. The marathon racer is a great halfway house between extreme minimalism and the risk of injury it carries.

Nike Free - running and strength training combined. I'm not on the payroll of Nike, but it is worth explaining some of the technical benefits of wearing the Nike Free range of shoes. Other shoe companies are beginning to release similar models so this discussion would equally apply to shoes with similar features.

Nike claim the Free delivers benefits similar to barefoot running (better biomechanics and strengthening of muscles in and around the foot). It’s tempting to write off the Nike Free as a brilliant piece of marketing, but there are practical benefits behind the hype. First and foremost there is no stiffness built into the Free range of shoes, by this I mean if you flex the shoe from front to back you’ll meet no resistance, try this with your everyday trainers and even some road racing flats and you’ll find the task a lot harder. Note: the flexibility of the shoe with the toe bent downwards towards the heel is probably more important than the usual marketing shots which show the toe of the shoe flexed upward.

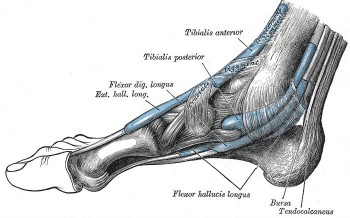

The flexibility of the shoe drives potential strength gains in the foot and deep compartment of the lower calf. In traditional trainers, there is usually a high degree of stiffness that takes over and does some of the work of the plantaflexors in the foot and lower calf. The result, these muscles get lazy and weak, compromising your capability to transfer forces generated by the bigger buttock and hamstring muscles. The ability to stiffen your foot is the role of the plantaflexors – small muscles that fulfill this role reside in the foot, but there are also three bigger muscles of which the tibialis posterior is the most well known, that sit beneath the soleus (lower calf) and gastrocnemius (upper calf). The tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus form the deep posterior compartment of the lower leg.

So what has that got to do with strengthening the feet? Actually a lot, the tendons attached to these muscles wrap underneath the arch of the foot and the toes - therefore when these muscles are strong enough they help the foot to stiffen and provide a stable springy platform from which to run. It’s not until you build some strength through your feet and lower calves that you begin to understand the true nature of running well. So, am I a believer in the Free as a useful tool for improving your running? Yes, but you need to be cautious, running in Frees is not for everyone.

I started running in Frees after I’d decided to improve my technique, so I’d already moved away a little from my initial hard impact heel striking technique that involved landing with my knee virtually straight, and foot well ahead of my body. If I were still running that way I wouldn’t wear the Frees unless I was being extremely cautious and consciously trying to correct those technical errors. If this is you, consider using the Frees in the gym or for walking as a transition step. If in doubt take the cautious path.

More than one model. There’s a really good case to be made for running in a few different shoe models. The case grows in line with the volume of running you are doing. The theory is that if you wear different shoes you will make micro changes in your technique and subject the body to a slightly different set of forces and repetitive movements. This might help you avoid chronic overuse type injuries, especially if you run big miles. It may also compensate for any minor flaws in each shoe design or a flaw in your technique accentuated by the shoe.

Throughout this book I also make the case for trying different movement patterns - in fact the best way to improve technique is to experiment a little with how small changes might make a big difference. Some different pairs of shoes can contribute to this process by stimulating you to do something slightly differently than you’ve done before. These sort of tactile experiments are excellent for your evolution as a running technician because they expose the body and mind to different stimuli that can help develop better running technique.

Barefoot. I’m not philosophically against the idea of barefoot running, in fact I like the concept a lot, the problem is that like particular shoe models and technologies it is not an answer in its own right. If you are an average runner (with technical flaws) who has traditionally worn supportive and well cushioned shoes, it stands to reason that adopting an all or nothing approach to going barefoot might be a little risky.

The point of this chapter is to explain that technique and muscle weakness (particularly around the hips) is the leading cause of injuries in runners. Shoes or lack of them definitely do not magically transform a movement pattern in your running that you’ve been using for many years. As I’ve indicated, I’m a fan of moving to lighter, less bulky shoes and to some extent a bit of barefoot running once your technique has improved. Be smart about it, if you’ve never run barefoot before then caution is your mantra.

If you run heel first with an extended leg well in front of your body your feet, shins, knees and hips are not protected because your hamstrings and glutes are not engaged. This is the way I used to run and I see a lot of people run this way. The problem for this type of runner throwing away your shoes is obvious - it’s then a guessing game as to which part of your body will break first. The same caution here applies to wearing Nike Frees for the same reasons, if your technique is bad, wearing minimalist or no shoes is a risk.

If you’re not convinced, hasten slowly, a few jogged laps and some barefoot run-throughs on a grass oval should tell you if you’re going to hurt from going barefoot before your technique has evolved to something more serviceable. I read a lot of commentators that advocate a few barefoot strides here and there - again, yes, but only if your technique and body can handle it. Be careful, because if you’re technique is compromised, even a few strides might lead to a nasty case of shin soreness.

Barefoot is an important means of stimulus, learning and building strength in your feet and lower leg plantaflexors. This could mean just walking about the house without shoes or just in a pair of socks when you’re doing some gardening. There are also specific strength exercises that I like to do barefoot to help stimulate strength in my feet - single leg squats and dynamic single leg back extensions are good examples. If you’re a good technician then you’ll be able to do more barefoot running. But I believe that you need to work on improving your technique before you make a transition to any meaningful volume or intensity of barefoot running.

Matching shoes to your running technique. When choosing the right shoe to match your running technique today, you should always have an eye on a future - one where you are transitioning to running with better technique. In a perfect world we would all be able to jump into minimalist or no shoes for all our running and this would somehow automatically correct years of muscle de-conditioning, poor coordination and technique. I don't recommend such a black and white approach. The reason is that improving your running technique is an evolutionary process; it requires strengthening and improved coordination of the muscles and practicing running with better technique. This takes time, months and years. Expecting your mind and body to adapt overnight is asking for trouble.

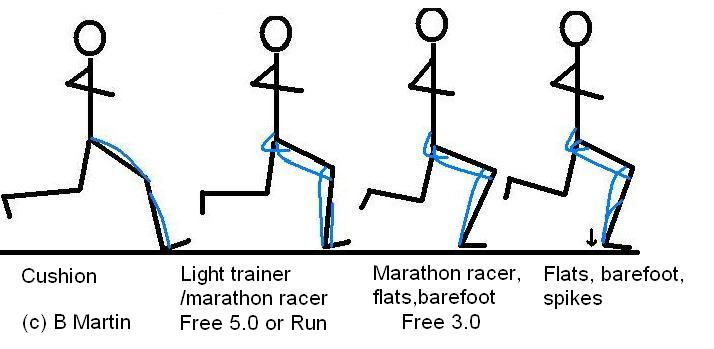

Here are some basic principles for choosing shoes. If your technique currently needs a lot of improvement and you want to continue running a decent amount of miles you should continue to wear a cushioned shoe for most of your running. Try and avoid wearing ultra heavy, stiff motion controlling shoes - a neutral cushioned shoe will give you better perception of what is happening under your foot. However, you should also buy a lighter trainer or marathon racing shoe to wear during some shorter jogs, strength training and drills. Alternatively, if your technique is solid, you may be able to wear lighter trainers or marathon racers for most of your running. Once you are technically very strong, then wearing genuine flats, doing some barefoot running and racing in spikes becomes possible. You should be looking to evolve to wearing less shoe - especially if your technique needs improvement. However, give your body a chance to adapt and make this transition gradual.

These principles closely align with the three phases of learning to run outlined in this book. As you progress to activating the correct muscle groups at the right time, your landing posture and position will gradually improve. Once you have the strength and stability to consistently activate your glutes and hamstrings so your foot always lands under a flexed knee closer to your body, you will be able to transition to wearing less shoe. Ultimately, as you fine tune your technique then the posture of the foot and ankle becomes the last piece of the puzzle to get right. Wearing shoes without much heel or doing some barefoot running at this point will help you get the feel for a more neutral forefoot landing posture. Remember, this doesn't mean staying on your toes.

Brian's perfect shoe. For me, the perfect shoe is one that is light, probably weighing less than 8 ounces or 220 grams. It needs to be firmly cushioned and have a small heel with a slight drop from the rear to the front of the shoe - if I’d run barefoot from birth I wouldn’t need this, but I still crave a little something under my heel as I develop the strength of my feet and deep lower calf muscles. I’m also not biomechanically perfect; it might be that I can eventually move to flatter shoes. I do some jogging in these, but I’m in no hurry to wear them all the time. I’m into taking some calculated risks and experimenting, but I enjoy my running too much to risk a major injury. Gradual evolution in shoes is the way to go for me, not revolution. The shoe must also be flexible, front to back and side to side. My feet and ankles are capable of flex, so must my shoe.

So what do I run in? For now I log most of my running in four shoe models. I’m not into endorsement one way or the other, but I like Adidas shoes at the moment, the cushioning is firm and flexible and they make fantastic marathon racing shoes. I wear the adiZERO Adios (mostly) and adiZERO Mana (sometimes) models that weigh about 7 ounces. These shoes are great on the road and even on trails, providing good road feel and springy response. I also run about half my miles in Nike Free 5.0s (sometimes) and 3.0s (mostly). Generally I try to rotate between the models so I don’t wear them on consecutive days. I’ve recently started to run more in Nike Free 3.0 and they’re great shoes, less heel than the 5.0s, but enough to keep me out of trouble. They’re especially good for practicing a more neutral foot strike because of the feel for the ground and smaller heel. I find the Frees good for running on uneven ground and trails. Initially I thought the risk of stone penetration would be too great, but this is somewhat mitigated by the ability to feel and react to the uneven surfaces in the forest. Occasionally I step on a stone that I wished I hadn’t, but generally I prefer the Frees on the rough ground to any other shoe. Does the Nike Free trail shoe exist? If it doesn't perhaps it should. I noticed recently that New Balance make a minimalist trail shoe and when this gets to Australia I will be keen to try it.

Over the years I’ve sampled plenty of other makes and models: ASICS, Mizuno, Saucony, Brooks, New Balance etc - I’m not saying these brands don’t make good shoes, they do, and they may have the model that suits you. The only way to find out is to buy a few pairs. Buy from a specialist running shoe retailer - chances are you’ll get the option to run in your prospective purchase before you get them home. It’s not foolproof, but it’s better than shuffling around in a pair of shoes locked together with a cable or picking shoes based on your foot type. Which shoe will be perfect for you?

Shoe buying tips from an expert. Mark

Gorski, former elite 1500m runner, coach and owner of the Melbourne

Running Company (a specialty athletics shoe retailer) was kind

enough to provide comments to me on this chapter and help provide

some guidance on how to buy a good pair of running shoes. He

suggests a few things to consider when buying running shoes:

- Bring your running gait analysis video and notes, including your

injury history.

- Have a pair of your normal running socks.

- Consider buying two pairs, wearing different model shoes can help

reduce overuse injuries.

- Bring your old running shoes so wear patterns can be

observed.

- Have your running gear, shorts and T-shirt in case it’s ok to

have a run in the shoes.

- Bring your orthotics or inserts if you have any.

- Talk about the type, pace and volume of running you’re

doing.

- Explain what surfaces you will be running on.

- Have an idea about what racing (if any) will you be doing.

Most importantly, keep an open mind and listen to the advice you receive, forget about brand loyalty and preconceptions, be prepared to try something different and get the shoes that best suit the way you move.

****