The training of distance runners today is the product of science, the teachings of legendary coaches and the exploits of a select group of resilient and gifted runners. Building mileage is almost universally accepted as the main pathway to greater performance levels. It’s hard to argue against the science combined with the achievements of elite runners punching out one hundred miles per week. Most popular running books and coaching philosophies mandate a mix of training based around developing cardiovascular fitness through long easy runs that are then supplemented by faster and more intense running sessions. I find myself asking the question: is there another way, or at least an alternative that might be more successful for regular, less talented and resilient runners?

I recently read an excellent book called The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Taleb explains that many success stories lead to the proliferation of sets of rules for accomplishment that are based around flawed assumptions. Yes, person A was successful by following a set of criteria including XYZ. However, if, of the total population following the XYZ doctrine, only three or four people out of one hundred thousand or more had such success, is it really a good methodology? Was person A’s adherence to the XYZ philosophy responsible for the level of success or was A lucky and representative of a phenomenon Taleb calls the survivorship bias?

Imagine a funnel that symbolizes any how to approach where the mouth of the funnel is the number of followers of a set of guidelines and the neck of the funnel the filtering method for reducing the number of followers down to a group of successful individuals. A funnel with a very big mouth that produces a relatively small number of success stories is indicative of the survivorship bias. Unfortunately, running is a sport where a large proportion of participants find themselves injured and on the sidelines more than they would like. Could it be that the generally accepted method of training has some flaws?

In running, there is a lot of literature based on the training methods of a few very successful individuals. Yes, they trained hard and used traditional training methods, but does this make their training a model for all to follow or are they representative of survivorship bias? I believe this is a conundrum not just for the recreational or club runner, but also for elite athletes. For the broader running community, the big mileage approach should definitely be closely scrutinized.

There’s an old adage in running about not adding more than 10% to your mileage in any given week, but just how realistic is this for the everyday runner? Should we just mimic our running idols and try and run big miles or is there another pathway to a more productive and enjoyable running? I believe there is. Following the training regimes of high level performers and the advice of their coaches is a high risk strategy for regular runners. Elite athletes are blessed with inherently good technique and resilient bodies that allow them to do more running without succumbing to injury. Wouldn’t we be better off focusing on mastering our technique first so that in the longer term we are skilful enough to handle bigger and more intense training loads? This chapter puts forward an alternative philosophy that is more forgiving on your body and allows you to consistently improve your technique and your running.

After you have a modest base. At this point I’m making an assumption that you’ve made improvements in your technique and that you’ve completed at least eight weeks of easy running as suggested in the earlier parts of this book. After you have this base and you’re feeling reasonably competent with your improved technique, you’ll most likely want to push on and start to do some harder running. This chapter is about how to modify your training to help enhance and maintain your running technique. It will explain my philosophy of modifying traditional training programs to suit the needs of a runner who is seeking to improve their technique, enjoy their running more while remaining injury free.

The objectives of this chapter are formulated to

give you some ideas to try in your training, and if you are a

coach, some modifications you can make to the training programs of

your athletes. As I mentioned earlier in the book, I’m a fan of

Daniels’ Running Formula (2005) so most of the comments about

training paces here are based around Daniels' system for matching

current ability to suggested training paces and types. His system

splits training into five running speeds and types: repetitions,

intervals, tempo, marathon and easy running. This chapter

explains:

- How to modify a traditional training structure to make it less

injurious and more enjoyable.

- Why long hard intervals are not ideal for someone making

technical improvements.

- That base training should be extended before commencing harder

sessions.

- Why tempo running and marathon pace training should be the first

harder sessions introduced.

- That tempo intervals make for good technique training.

- Why hill efforts are good for technique and good for

strength.

- That shorter repetitions are preferable to longer reps in the

early stages.

- How trails, with rolling terrain and decent hills force you to

reset your technique.

A typical training structure. If I

examined the training structures outlined in your favorite running

book I would probably find an approach based around developing

fitness and running performance by training various aspect of your

fitness. For distance runners this approach will be focused on a

mix of endurance, lactate threshold, Vo2 max training and speed:

see Daniels' Running Formula (2005) or Advanced Marathoning (2009)

by Pfitzinger and Douglas for further explanation of these

concepts. All of this assumes that your running technique is sound

or will improve spontaneously through training and that all you

need to do is compile many weeks of training that look something

like this:

- Monday: rest day (if you’re lucky)

- Tuesday: 5 to 8*1000m at 5km race pace

- Wednesday: long easy run

- Thursday: 8*400m at mile race pace

- Friday: easy run

- Saturday: Race or lactate threshold (30-40 minute tempo

run)

- Sunday: long run (20km +)

This is some seriously solid training. Keep in mind that elite runners will do this, their gym sessions and double run many days. They’ll probably run 100 miles (160km) per week even if they are specializing in 5000m races. Is this a structure that you want to follow if you’re not an elite runner or have a questionable running technique? Most likely not, it’s a recipe for developing injuries and big physiotherapy bills.

Keeping strength, technique and fitness in

balance. What I’m suggesting is a modified, more flexible,

lower risk and perhaps more effective philosophy of running

training. Under this approach the runner needs to keep their

technique, strength and fitness levels in balance as much as

possible by improving these elements simultaneously. By this I mean

all running should be able to be performed with correct technique.

If you can’t complete a training session with good technique then

you are not fit or strong enough on one of three levels:

- Your technique didn’t hold up mentally, your concentration

slipped: you were not mentally trained enough or muscles not well

coordinated.

- Your muscles couldn’t produce the strength to generate

good technique for a sustained period: your muscles are not strong

enough.

- Your heart rate and respiration (breathing) was so high

and labored that concentrating on technique became impossible:

you’re not fit enough.

This approach is designed for normal runners, who want to train in a way that puts technique first and keeps training volume and intensity in perspective by only increasing these with technical progression. It is an approach that seeks to minimize the risk of developing overuse injuries that develop from overreaching in volume and intensity before your body has the strength and technical capability to absorb that training. I’m not saying you can’t eventually run 100km+ per week, but I’m suggesting you take a long time to build up this level and ignore any suggestion that you can simply add 10% to your mileage week after week. If I followed that rule and was beginning to build up my running from 40km (25 miles) per week I would be running 160km (100 miles) in about four months. Is that really practical or smart?

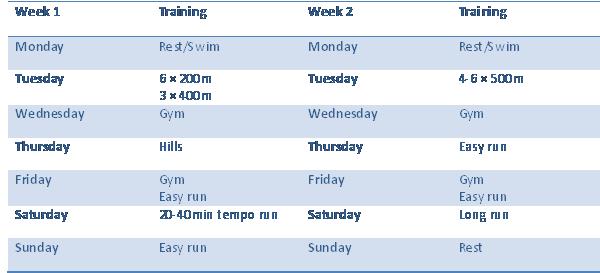

Why it makes more sense to think about a 14 day training cycle. Part of the problem with most training programs is they try and fit in training sessions that are designed to stimulate too many physiological adaptations every week. This inevitably leads to a situation where you will be doing three to four hard sessions a week. I say four because we all tend to do a long run on a Sunday (one of those traditions) regardless of whether we raced or did a hard session on Saturday. Add this to the 1000m or mile intervals and 400m repetition days you did earlier in the week and you have a lot of hard running over four sessions.

Some people would say that the long run is an easy day, but I argue strongly against that view: even if you do it slowly, running from between 70 minutes and two and a half hours is very taxing on the body. This is especially true if your technique is not sound. While you might be able to persist and push through the pain to run those long miles, your body will be sore and weak for many days afterwards. An alternative is to adopt an approach to work on two or three harder or moderate intensity sessions per week and alternated the type of sessions on a week 1, week 2 schedule. This schedule is one that does not have races included (racing should be done sparingly). Note: the suggestions here are not intended to be a full training program, rather a template for modifying the many detailed programs in books such as Daniels' Running Formula (2005) and Advanced Marathoning by Pfitzinger & Douglas (2009).

This schedule includes 9 days of running out of 14 allowing plenty of time to recover and also to allow priority and focus on the strength training sessions. Two or three strength and coordination sessions per week are a good number to aim for. If you can fit in a swim once per week that’s a bonus that helps you recover. This type of program gives you variety, a focus on strength and the ability to do every run with good technique because you will not be sore or over trained. Only do good quality running technique in any session - especially on the long run, which can easily disintegrate into a shuffle or a slog that does nothing to help your running technique. Doing it fresh and only once a fortnight will allow you to complete it with better technique and at a slightly faster pace. You can change the days depending on your personal circumstances and schedule. Note: the longer you run, the more you should think about how you include the long run into your training. Runners building up from 60 minutes to 90 minutes of running will likely be able to get away with a long run on most weeks. But keep a close eye on how your body is reacting to the training. If it takes you until Thursday to recover from a Sunday run of 80 minutes then you might need to back things off a little.

Daniels (2005) has some great information about the rate at which a runner will lose fitness because of any layoff. Fitness takes a long time to dissipate; therefore you don’t need to be developing every type of physiological adaption all the time. He also espouses the principle that you tend to accumulate the benefits of previous training over the longer term. This type of program builds on those principles as it seeks to enhance fitness and strength over a long period.

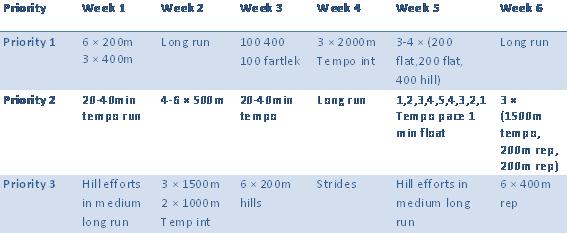

Keeping things fresh over six weeks. To add an even longer term view we can change the priorities of each training week and session by modifying the focus of the harder sessions in that week. Variety is the spice of life and in running it really helps break up what can sometimes seem like hard work. Churning out the same sessions week after week is a sure way to burn out and get injured. Under this model you do each type of session at your best (i.e. rested and strong). The priorities don’t relate to days, but you should get emphasis to priority 1 & 2 sessions and skip the third priority session if tired, sore or just living a normal busy life. Note: to keep things simple I’ve dropped the gym, swim and rest days, but these should be factored in as priorities by you and your coach depending on your season plan, fitness and progression. For more information about training please visit http://www.runningtechniquecoach.com.

Tempo/ threshold runs. These runs are the mainstay of most distance running training programs and are designed to help build your capacity to delay the onset of excessive lactic acid accumulation. From my perspective they are also a great tool for practicing your running technique at a solid but not stressful pace. In these runs your heart rate should not be too close to your maximum and your breathing should be steady and under control. This is the perfect intensity to practice holding your technique together. In my own running I commence with a 3km tempo run when building up my fitness. I base my pace on those suggested in Daniels' Running Formula (2005), but you want to run at a pace that allows you to keep control of your technique. If you can’t hold it together for 3km then you need to slow down or break your session into shorter tempo intervals of 1000m or 1500m. As you accumulate fitness and strength you will be able to make this session longer to the point where you might be able to run at good pace for 10km holding correct technique.

Cruise intervals. Cruise intervals (Daniels, 2005) are a fantastic way to practice your technique. The short durations of the intervals 1000-2000 meters means you get the chance to reset your technique with each interval. You are much more likely to run a session of cruise intervals with better technique than a complete 40 minute tempo run because you have a modest recovery period between each interval. Recreational and club level athletes should definitely consider substituting longer tempo runs for this type of training. You can still do a sustained tempo run of a longer distance, but only when you’re ready and perhaps consider doing it less frequently.

Hill training. Hill training can have a number of different variations and different types and paces of running can be modified with a hill or hills involved. In the relatively early stages of making technical improvements consider doing some controlled hill efforts (not sprints). This would be after you have an established base and are competently able to apply your technique. The idea is to not destroy yourself doing these efforts. Pick a hill with a steady incline that is not too long, probably about a 200 meter rise. Run four to six controlled efforts.

The key with these efforts is not to go all out, but to ease up the hill using good technique. This means keeping the emphasis on driving with the hamstrings and glutes and keeping your ground contact short: a powerful stride with good turnover. Think about bouncing your way up the hill on your butt. The slope of the hill tends to get your glutes firing more than if you were running on the flat because your foot contacts the ground earlier and forces you to lever yourself up and forward using the butt and hips. Try not to lift your legs up the hill with your quads. Stay in good tight formation to reinforce your technique. This type of session also provides the side benefit of a moderate intensity strength workout: your butt and hamstrings should feel it a little in the following days.

Repetition and speed training. Repetition or speed training is not as fast as the name implies. Under the Daniels (2005) approach, repetitions of 200m, 400m, 800m are to be performed at a pace similar to your current mile race pace. For me in the past year I’ve run my 200m repetitions at between 38-41 seconds and 400s between 79-82 seconds (87-91 seconds on 400m hills). Run at a pace where you are in control of your technique, especially when doing longer reps such as 400m. If you can't sustain good technique for 400m either reduce the pace or the length of the repetition. Whatever your current ability level some experience running a little bit faster than your race pace for 5km is very beneficial.

In terms of modifying regular training programs I’d suggest keeping the length of your repetitions quite short. This is more important very early after a technique change and/or in the first phase of quality faster running your include in your training build-up. The reason for running short intervals is that it’s easier to maintain good technique for the complete effort. For example: when you’re not at peak fitness it’s difficult to run out a full 400m repetition with good technique. On the other hand it is much easier to hold it together over a 150m, 200m, 250m and 300m rep distance if you are beginning to build your strength and fitness. Don’t take on repetitions longer than 300m until you’re comfortable being able to execute six to eight 200m or 300m in succession.

This might make your initial repetition sessions seem quite skinny on quality running, but what’s the hurry? In my current build up I delayed the introduction of 400m repetitions for a few weeks, so my training sessions included only 1600m-2000m of harder running. In the early stages this is plenty. For you it might be less (or more), don’t be embarrassed about doing sessions that have you jogging a 3km warm-up, running 5*200m or 4*150m. The idea is to practice your technique at faster speeds, so try and keep it in perspective.

You want to run these reps without feeling like you’re blowing up - if you’re too out of breath to maintain your technique you are running too fast, the repetitions are too long or you’ve done too many. You should also take a full recovery between each repetition, if it’s a 200m have a full 200m jog (and walk if you need to) to recover. If you feel like having a stretch or stop for a few moments to reload your technique, do so. This ensures you’re mentally ready to execute the next repetition as well as the last. You’ll find you can build these up quite quickly so don’t be in a hurry to overdose on volume or intensity too early in your program.

Interval / Vo2 max training. Intervals are generally acknowledged as the most demanding training there is. It’s hard to disagree, these sessions are usually done over long distances 800m-1600m at high intensity (5km race pace or slightly faster) with short recovery periods. The idea of these training sessions is to build race fitness. They are tough because they’re done at an intensity that brings you relatively close to your maximum heart rate over a long period. This means they are the training session where it is most difficult to maintain good technique. You are tired, breathing heavily and the intervals are long and demanding - for this reason I recommend avoiding this type of training in the first season if you have made major technical changes. Before you say, “you’ve lost the plot, these sessions are my bread and milk,” stop and think for a minute.

If your technique has improved you’ll find that your tempo running pace will be faster than it was, so it’s likely you’ll be running faster at a lower heart rate, intensity and pain level than before. Enjoy this process, feeling good and running your fastest time is fantastic, there’s plenty of time later to add the grind of long intervals and fully maxed out racing. Until then avoid this type of training and run your races at tempo intensity - at least until the last two laps!

Long runs. The long run as a training session is essential as there is so much physiological and practical evidence of its importance in training the abilities of the muscles to build strength, efficiently process oxygen as well as store glycogen (energy). The problem I have is not with the training or its benefits - these are without question. My question relates to its usual placement and frequency in most training programs and the consideration that it is more or less an easy run. The reason I say this is that for decades runners have been faithfully heading out on their long run after smashing themselves badly in races of various lengths the day before. Invariably this means the body is already weakened and sore from the previous racing day or harder session and you’re now going to subject it to between 70 minutes and two and a half hours of running. Your mechanics are suspect, you're favoring one side because you’ve picked up a niggle the day before and you’re just plain tired. How can you hope to keep up a decent pace or technique with this scenario?

My approach is to treat your long run as a moderate to hard intensity training session and do it a bit harder every second week. This could mean building up to marathon pace is the closing stages or including a long hill to increase the intensity. Make sure you’re fresh, i.e. don’t do 8 by 1000m the day before. Have at least 2-3 days between it and your last hard session and maybe even freshen up with a rest day before. This way you can run it with better technique and enjoy it a whole lot more that stumbling around painfully week after week until you get injured. If your mechanics are compromised by soreness and/or a poor technique, the long run will expose any weaknesses due to the sheer duration of running. If you've completed a taxing race the day before, it's a good idea to keep your Sunday run easy and a bit shorter. For example, my long run is currently at about 80 minutes, but when I've raced the day before I skip it and do an easier run of about 50 minutes as recovery.

Trails. A lot has been written about trail running and its benefit around preventing athletes from running too hard on their easy days, getting athletes off hard surfaces and just enjoying nature. I agree with all of that completely. There is also an extra element that supports the inclusion of trails into your regular training routine. Running on uneven and undulating ground with lots of twists and turns does force you to slow down; it also forces you to reset your technique. I find these types of runs a great way to continually practice launching correct technique. If you set off on a 40 minute tempo run on a flat road, you get to set up your technique once and then try and hold it together: not easy if you’re in the process of technical improvement. On a trail you need to slow, stop and start as you negotiate obstacles: other runners, mountain bikes and occasional wildlife. Each time you do this is an opportunity to practice enacting your mental cues to launch good technique. Short sharp hills can also really help get your glutes and hamstrings firing. Mentally I find running trails a real holiday, running a medium length trail run of about an hour or so is a great alternative to a long run if you're feeling flat or unenthusiastic about pounding out 20km on the road.

Racing, fun runs, half marathons and marathons. As a final word on training with focus on good technique, we come to the crunch, racing! If you’re looking to run a personal record/best then follow the advice of Jack Daniels - run even. By this, I mean you need to start and run the middle stages of your race at a pace that you can sustain each and every lap if you are on the track or each kilometer/mile if you're on the road. If you’re racing on the track you need to convert your goal time into a per lap time - most good training guides will have a conversion table. If you’re the king of the roads, then a per kilometer or mile pace might be what you manage your effort with. Your mission is to think about two things when you first return to racing after improving your technique: maintaining an even pace and holding your technique together.

If you reflect on this, running an even pace is all about maintaining a consistent technique - elite runners do this as a matter of course. Next time you attend a race, take a stop-watch and click off the lap times of the better runners, you’ll most likely find (aside from the finishing kick) that the lap times are very even. Thinking about your technique also gives you a focus other than your competitors and the inevitable discomfort that comes from pushing yourself close to your limits. Don’t race the competition (at least initially) - race yourself and the clock.

The trick is to ride the line between controlled hard running and blowing up, do this until two laps or a kilometer to go, and then start pushing your intensity levels the maximum. With one lap remaining drive to the line with everything you've got, you’re breathing at this point can get out of control, but you should hang on to your technique even in the final surge to the finish. Just imagine you’re doing a session of 400m repetitions and hold it together to the line. Look at the clock as you gather yourself after the race and enjoy the satisfaction of running faster than you ever have before.

You can read about the day I cracked my personal best for 5000m here - I'm still buzzing.

****

If you enjoyed this book and would like to learn

more about running technique and some of my other thoughts about

training philosophy please visit:

http://www.runningtechniquetips.com

http://www.runningtechniquecoach.com

####