CHAPTER 1

The Conceptual Framework: Nation-States and the Politics and Identity of Exiles

The movement and resettlement of people from one land to another has been a significant part of human history. Natural disasters, war, and changing economic, social, and political conditions have forced people to relocate over and over again. With the rise of an international economic system the movement of people and the communities formed in new lands were closely related to colonial conquests. Colonial armies were important means of generating migrant streams of soldiers who would later settle many of the colonies.1 This was particularly true of the Spanish Empire. In other cases, such as the British Empire, colonial settlement patterns included families as well. In general, the direction of the movement of people was from the metropolis to the colonies.

The global exchange of capital and labor reversed this direction, and the movement flowed from the periphery to the metropolis. In the Western hemisphere the United States exported finished products and capital; Latin American countries exported raw products and labor. The rise of the nation-state established procedures through which the movement of goods and people was processed, thereby politicizing population exchanges. The state became the regulator of such exchanges. The nature of these processes and the conditions in which they occurred had an extraordinary influence on the development of the politics and identity of diaspora communities—that is. communities of people from one nation-state living in another.

Nation-state, an eighteenth-century phenomenon that finds its maximum expression in the twentieth century, defined the unit of political organization as one contained in a geographically demarcated space. Under this notion of organization, public power is organized and contested within the geographic boundaries of nation-states, which also define the economic and social organization of societies.

Within the nation-state construct, then, the state regulates the public affairs of the nation. Yet the precise nature of these regulatory functions, and where in the state bureaucracy they are located, has varied from nation to nation and indeed even within national boundaries. Activities that pertain to relations with other countries, however, are generally clustered in the foreign affairs of the state. While immigration issues have tremendous domestic implications, they are generally attached to foreign policy matters.

The very notion of citizenship is intricately linked to the rise of the nation-state. With the formation of nation-states came new conditions that defined the rights of individuals, particularly in relation to the state. These included legal categorizations that defined who would be entitled to these rights. Thus, citizenship became a right to be granted or denied by the state. While legal variations exist about how citizenship is conferred (in German law it is passed from parent to child; in Spanish, French, and British law, place of birth is the determining factor),2 all nation-states make citizenship and residency a requirement of political participation. Citizenship is not extended to all residents, and immigrant participation in public affairs is usually dependent on legal status; legal but nonnaturalized residents and “illegal” residents, for instance, are not allowed to vote.

Furthermore, citizenship assumes loyalty to a single state. Even when multiple citizenship is permitted, as is the case in the United States, an immigrant is required to swear an oath of allegiance to the United States in order to become a naturalized citizen. Naturalized citizens—that is, those not born in the United States—are expected to leave their homelands behind when it comes to public affairs.

The “nation” element of the nation-state concept carries certain embedded assumptions, particularly with regard to citizenship. One of these is the conception of the nation as socially and culturally homogeneous. Those who are citizens are expected to have a common cultural base. Even in the United States, which initially defined the body politic according to criteria such as property ownership, gender, and race, a romanticized abstraction of the androgynous, classless, raceless citizen nonetheless prevailed.

Social and political identity are closely linked precisely because of the coupling of nation and state—the nation being the soul, culture, history, and social structures, and the state serving as the regulator of these elements. Political identity is defined and regulated by the state. But the concept of citizenship does not exist in a vacuum, disjoined from other facets of society, particularly in societies marked and divided by racism or “racialized” ethnocentrism in which factors such as race and national origin have determined who is to be awarded citizenship. Nor is citizenship isolated from questions of politics, as is the case for totalitarian regimes that demand loyalty in order to grant citizenship or even to recognize an individual as part of the nation. It is in this intersection that a recognition of social identities, including ethnic and national identities, is critical for understanding who has access to the political system and. in turn, how communities excluded from the political process organize in order to be included.

Inquiries into nation-states and political organization lead to the topic of political identity. As such, this book also explores questions pertaining to the identity of diaspora communities in the context of changing nation-states at the end of the twentieth century. Identity, as the term is used in this book, is a social construction that requires ongoing negotiation between the individual and the broader society. Social and political identity consists of at least two important dimensions that act independently of each other and interact as well: the society’s construction of an individual or a group’s identity; and the individual’s or community’s self-constructed identity.

Despite the larger forces at play, the study of immigrant communities in the United States usually begins with an attempt to understand the motivations that contribute to an immigrant’s decision to leave the homeland. Yet individual motivations alone do not necessarily explain a social phenomenon. Social science literature has begun to uncover the conditions in sending and receiving countries that contribute to immigrant flows. This has led to a debate over how to classify those arriving in a new nation-state. Social science literature of the past fifty years distinguishes between immigrants (those who leave their homeland voluntarily in search of better economic opportunities), refugees (those forced from their homeland for a variety of reasons), and exiles (those expelled from their homeland for political reasons). These distinctions influenced the legal status granted to incoming migrants. Such distinctions, however, fail to capture what is surely a more complicated phenomenon in which these various factors combine in different ways to create unique diaspora experiences.

From these resettlement experiences, moreover, different kinds of social formations have emerged. Will the exiles return home when political conditions change? Will immigrant communities be assimilated within the dominant culture in the second generation? Are they detached pieces of their nation of origin, colonias that tenaciously preserve their original culture? Or do these communities forge altogether new identities that both preserve their own culture and alter that of the country they come to inhabit, both physically and emotionally, thereby calling for a new vision of politics?

While social science literature has tried to categorize movements of people and their settlements according to various criteria, Khachig Tölölyan suggests using the term diaspora. He writes in the introduction to Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies, “We use diaspora provisionally to indicate our belief that the term that once described Jewish, Greek, and Armenian dispersion now shares meanings with a larger semantic domain that includes words like immigrant, expatriate, refugee, guest-worker, overseas community, ethnic community.” “Cubans,”he goes on, “are a transnational collectivity, broken apart by, and woven together across, the borders of their own and other nation-states, maintaining cultural and political institutions.”3

Diaspora communities provide windows through which we can look at state structures to understand both their nature as well as their changing dynamics in an era of transnationalism. After all, diaspora communities have experienced both the porous and intransigent aspects of state borders in this century. Many have learned firsthand that organizational and emotional schemes based on the notion of singular nation-states, such as distinctions between home and host country cultures, assume a homogeneity in these locations that simply does not exist. In fact, it is not uncommon for immigrants to return to their home countries only to find them more “Americanized” than the enclaves they have built in the United States or Europe. Today images and culture pass between countries easily and rapidly, thereby producing and making available multiple sources of culture.4 Global youth culture, for instance, is ubiquitous, as is the successful marketing of “ethnic” culture. Obviously, this commodification of culture beyond national boundaries is not the same as genuine political empowerment, but with regard to identity issues it changes the available points of reference people have in which to anchor their selves. Today we may be witnessing the rise of a transnational identity, one most visible in those who have crossed many borders—an identity that, for communities of diaspora people, is grounded in multiple cultures and reflective of a hybrid experience.

The changing nature of the frontiers of nation-states also suggests that politics itself—the notion of who is entitled to participate and where and how—may change.5 Particularly within diaspora communities, people are affected by actions carried out by governments over which they have little influence. Their newcomer status in host countries affords diaspora communities limited voice in public affairs. Home country governments likewise make decisions that affect diaspora communities residing beyond the state’s geographic jurisdiction. Some countries are extending voting rights to their communities abroad, while many host countries are limiting, or in some cases removing altogether, the few avenues immigrants have had to voice their opinions. Few analytical and legal concepts go beyond the nation-state as the parameter for political participation that can accommodate the exile’s involvement in both host and home country politics. An in-depth look at the evolution of one diaspora community raises questions about the limits of the avenues available for meaningful engagement in politics by such groups.

National Security States and the Movement of People

While all nation-states share certain characteristics, they have particular formations as well as distinct regimes.6 The state in the United States changed radically as a result of its engagement in war. The beginnings of the surveillance state can be traced back to the Woodrow Wilson administration’s obsession with loyalty during World War I.7 But the consolidation of the national security state occurred after World War II. The U.S. state apparatus emerged from World War II radically transformed: for example, the percentage of federal employees involved in activities related to national security rose from 30 to 70 percent.8 This transformation also resulted in an increased proportion of federal monies spent on national security activities.9 These changes occurred in part because of extensive U.S. participation in World War II: the entire economy had been geared to war-related activities. The effect was a militarization of the economy that could not easily be dismantled after the war.

Another change that had major ramifications for the development and implementation of U.S. foreign policy was the emergence of an executive branch office dedicated to intelligence gathering. The fight against fascism had given birth to a bureaucracy that combined covert government activities and foreign intelligence in a single agency known as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The OSS was later transformed into the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), an arm of the executive branch whose function was to carry out espionage for the president. The CIA accrued enormous power in part because its creation, development, and ongoing affairs were kept outside the public view.10 Moreover, because the ethical rationale behind foreign intervention in the fight against fascism went largely unquestioned, the CIA received “the same mantle of morality” that the OSS had enjoyed.11 Although the State Department had once been the principal actor in the implementation of U.S. foreign policy, after World War II the CIA became a key player as well. From the start secrecy was the modus operandi for the CIA: even its originating charter has not been made public.

The National Security Act of 1947 also created another executive branch office called the National Security Council whose role was to coordinate foreign policy functions for the presidency. The ideological justification for these structural changes came in the form of the National Security Doctrine promulgated by Harry Truman, under which the traditional concepts of war and peace were obliterated. Constant war was considered the normal condition, and, as a result, there was always an enemy to be confronted.

The emergence of the Soviet Union as one of the victors of World War II and its expansion into Eastern Europe polarized the wartime allies and redefined the international power struggle. Prior to World War II the Soviet Union was viewed mostly as a peasant state, but Joséph Stalin’s rapid modernization campaign and the usurpation of vast territories after the war gave the Soviet state an economic advantage it had not had before. After World War II both the United States and the Soviet Union defended their right to maintain a presence in Europe. They also defended, just as staunchly, their respective political and economic systems, which were, of course, diametrically opposed to each other. The Soviet Union had a one-party political system in which collective rights superseded individual liberties and a centralized economy under the control of the political apparatus. The United States prided itself on its two-party democratic political system and its protection of individual rights. Free enterprise and relatively little government interference characterized its economy. These two irreconcilable perspectives led to an intense military, ideological, and political conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States that came to be known as the cold war. As Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote, “The Cold War in its original form was a presumably mortal antagonism arising in the wake of the Second World War between two rigidly hostile blocs, one led by the Soviet Union and the other by the United States.”12

This ideological battle also influenced the organization of policy-making within government. Within the United States, foreign policy matters are dispersed. The U.S. Congress had much greater influence in making foreign policy prior to World War II; since then, however, foreign affairs have been concentrated primarily within the executive branch. These functions are spread among various departments, including the Departments of Defense and State, as well as the National Security Council and the CIA. The Commerce and Justice Departments (the latter of which houses Immigration and Naturalization Services) have also played a role in shaping foreign policy.

The cold war further institutionalized the state’s role in the movement of people in the twentieth century. This resulted in part from a hypersensitivity to national security concerns that made émigrés from socialist countries potential spies, and vice versa. Yet émigrés also had symbolic value in the competition between these two antagonistic political and economic systems. For instance, the U.S. Congress authorized and funded the executive branch to set up special programs to relocate refugees from East European countries to the United States. Within socialist countries the control of population movement was essential for maintaining internal order. Therefore, policies regulating the movement of people had not only economic but also political functions.13 Even those immigrant flows perceived to be primarily economic may acquire political significance. Today, for instance, the debate in the United States about immigration from Mexico has acquired a political significance in the electoral arena.

The Cuban revolution of 1959 restructured class and power relations on the island. Policies were instituted that greatly redistributed wealth and other societal benefits. The revolution was deeply rooted in the struggle to define a nation and institute a just social program; it also had ramifications for U.S. hegemony in the Caribbean. The Cuban revolution had a major impact on the post-World War II standoff between the Soviet Union and the United States. The dynamics set in motion by an internal revolution were played out in the world arena. For the United States the nationalist revolution was perceived as a threat to its national security, as an island that had clearly been in the U.S. sphere was now quickly moving into the communist orbit. Soon, the Soviet Union had established a beachhead ninety miles from the U.S. coast.

In Cuba the “defense of the revolution” against outside threats became a rallying point. National security was the cornerstone of the philosophy of the emerging government. In much the same way as with U.S. policy, internal policies in Cuba fueled the formation of the Cuban exile. Cuban officials have generally dealt harshly with internal opposition; their policies at times encouraged dissidents to emigrate, while at other times they punished those who wanted to leave. Once abroad, with rare exception, exiles were cast as enemies of the revolution. The fact that people fleeing communism acquired a positive symbolic value for the United States furthered the process of demonizing those who were leaving Cuba. This naturally affected the movement of people off the island and, consequently, the politics of émigré communities.

In this context the relationship to host and home countries acquired a political significance for Cubans not normally ascribed to other immigrant communities. On the one hand, it emerged from a revolution that challenged U.S. hegemony. Thus, harboring refugees from revolutionary Cuba was of strategic value in the war against communism. Yet across the Florida Straits, leaving the island was equated with abandoning the Cuban nation, with treason. The relationship of the émigré community to the host state and home state, then, is defined at least in part by the national security interests of both states. Therefore, these must be taken into consideration in analyzing the unfolding of exile politics as well as understanding the development of the community. Some scholars have periodized Cuban immigration into various waves, taking into consideration Cuban and U.S. policies that determined the way people could leave and enter.14 Each wave has also been described according to the socioeconomic status of the immigrants and their political perspectives once in the United States.

The study of Cuban community politics could be conducted through the traditional prism of ethnic groups and foreign policy, a literature that assumes the possibility of democratic participation in foreign policy decision making and asks how interest groups affect foreign policy.15 This traditional approach seeks causality in the action or preferences of individual actors or organizations and not their interaction with larger historical and structural factors.

In particular, the backdrop of the cold war against which Cuban exile politics unfolds makes such an analysis inadequate. The question posed here is not how ethnic groups influence foreign policy but, rather, how the foreign and domestic policies of host and home countries have influenced the politics of émigré groups, particularly Cuban exiles. The distinction between “foreign” and “domestic” politics is curious in light of the continuous interrelationship between these forces. Nonetheless, the two terms connote different structural locations within the state apparatus. The foreign policy dimension takes into account policies aimed at other states, whereas domestic policies play out within the confines of a particular nation-state. These include activities in the electoral arena.

In this sense the study of the development of Cuban émigré politics is a study of the development of state structures and ideologies.16 How do state agencies interact with émigré communities, and what happens as a result? How do states construct this relationship ideologically?17 These questions must be asked of host and home country states. Hence, each chapter in this book takes into account both U.S. and Cuban policies affecting Cuban émigrés.

My emphasis on structural elements does not imply that individuals or communities are mere victims of historical circumstance but, rather, that the menu of choices for political action, particularly in the foreign policy realm, is determined by a constellation of factors shaped by forces larger than individuals. The state, a key actor in foreign policy decisions, has a series of resources it can wield to influence the outcome of politics. This perspective does not deny that émigré groups may acquire their own interests that at times run contrary to state interests or that émigré groups can under certain circumstances act successfully on their own. Furthermore, émigré groups are not monolithic but, instead, are composed of ever-changing levels of cohesion and diversity. There is a growing literature on Latinos that explores the engagement between Latino diaspora communities and their host and homelands, particularly in the context of globalization.18

Politics and Identity

The rise of the United States as a military world power influenced not only the nature of state structures and the movement of people but also the notions of who was entitled to participate politically. The very idea of civil liberties that characterizes the U.S. political system did not develop a body of case law until World War I, when the Woodrow Wilson administration and the standing Congress criminalized certain forms of expression, belief, and association. Using the Espionage and Sedition Acts, over two thousand people were prosecuted, many of them immigrants from countries with which the United States was at war.19 The anti-immigrant hysteria unleashed by these campaigns cast a dubious light on the loyalty of “hyphenated” Americans—a term that acquired a pejorative meaning suggesting divided loyalty between country of origin and the United States.20 The “other” was a foreigner. This scenario was repeated during World War II. when the U.S. government again orchestrated a repressive campaign against individuals of German, Italian, and Japanese ancestry, culminating in the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans in internment camps. The message sent was that, under certain circumstances, relations with home countries could be construed as a criminal act.

This perspective contributed to a notion of citizenship that placed a premium on loyalty to a single state. It is useful to note the political origins of this assimilation standard of loyal citizenship because it may help us to understand part of the tightly woven myth about the American melting pot and its epistemological corollaries. Immigration from Western Europe to the United States was at a peak at the end of the nineteenth century. While at war with Europe, patriotism and loyalty to the United States were expected. People rallied under the banner of “Americans.” Connections to homeland and even outward cultural expressions such as speaking German in public were discouraged and in some cases even criminalized. Hence, the myth arose that these communities had severed ties to their homeland and were now fully American.

It is not clear whether members of immigrant communities did indeed voluntarily cut their ties to the homeland or, rather, if it was simply too difficult to maintain such ties or too unpopular to acknowledge them. In a study of ethnic Chicago, for example, historians of various communities noted a persistent interest in homeland issues among immigrant groups even at the turn of the century.21 (Curiously. Benito Mussolini’s Italian government was the first to engage in a state-sponsored project to reach out to its communities abroad in hopes that they might influence U.S. policies toward their home country. National sentiment was present even if not displayed publicly.)22

Repression against immigrant communities contributed to the political ethos that it was desirable to become Americanized—hence, the idea of the melting pot. The notion of assimilation assumes that individuals can choose whether or not to become part of a new society regardless of how that society may view the individual and his or her group. On the valuative end integration is not only a desirable goal but a forward-looking one as well; shedding one’s ethnicity is a sign of leaving behind that which is old and replacing it with something new.

This perspective found its way into the social sciences in the form of the assimilation model and the acculturation models that succeeded it. These models share many of the conceptual underpinnings of the notion of citizenship by assuming the primacy of the nation-state as the main organizing unit of society. In political science the conceptual underpinnings of the assimilation framework are found in the political socialization model that predicts the following: immigrants arriving in the host country initially refrain from politics because they are preoccupied both with home country issues and with adapting to a new country. By the second generation ties to the homeland have weakened and political involvement begins, first at the local level then moving to the national level. By the third generation the political agenda may include international concerns; at this point, however, such concerns are unrelated to one’s country of ancestry, as ties to the homeland are presumed to have been severed. This view of political participation made sense within a pluralist conception of politics as a product of individual and organizational efforts.23 In this framework individuals and communities organized to exert pressure on a political system that would provide outputs the community needed.

The political socialization model is related to the classic assimilationist view of immigrant identity, which predicts that by the second generation immigrant communities lose their affective and cultural ties to the homeland and identify themselves with the new host country. In the United States, then, the second generation would be American. Against the predictions of this model, however, ethnicity prevailed. The notion of the hyphenated America, cast in a more positive light after World War II, permitted immigrants to retain some connection to their ethnic past, but with an important caveat: activities related to one’s cultural identity would be relegated to the private sphere, while within the public sphere everyone would be encouraged to become American. The concept of being an American—that is, a citizen—has carried a series of cultural and racial constructs from the beginning. Initially, cultural homogeneity was equated with racial purity. Over time anything that made people different—religion, for instance—was relegated to the private arena.

The hyphenated explanation of cultural identity complemented the idea that an individual must be loyal to only one state. In this sense it fit well with liberal notions of democracy that conceive of the public arena as a place in which individuals, not groups, participate in the political process. And, although group identities, ethnicity, and gender may be used as tools to mobilize and appease the electorate, rights are defined in terms of the individual.

The political socialization model was based on the experience of many of the immigrant communities that came to the United States at the turn of the century, an era of extraordinary industrial growth and relatively weak governmental structures predating the emergence of machine politics, particularly at the local level. These immigrant communities thus were incorporated economically into the mainstream, which in turn facilitated their political incorporation.

The political socialization model assumed that anyone who wanted to could participate in the process. It did not take into account the fact that in many host countries immigrants are neither welcomed nor allowed to assimilate. In addition, émigrés from countries with a neocolonial relationship to the United States, marked by U.S. domination both politically and economically, have a different relationship to the United States as host country than do émigrés from European nations. This is not to say that European immigrants did not face discrimination once in the United States, but the situation is different for immigrants from Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America, all of which have had a neocolonial relationship with the United States. The relationship of dominance has been accompanied by a view about the inhabitants of these regions that has included a process of considering their inhabitants nonwhite—a negative categorization in the dominant culture.24 This view has been extended to immigrants as well, so that individuals of Latin American origin are often considered “brown.”

The political socialization model, which assumed that integration was possible, did not deal with institutional racism. Therefore, when communities were unsuccessful in achieving formal political incorporation, social scientists asked what was wrong with the immigrant groups in question. Interestingly, the answer was usually that the communities resisted assimilation. Ties to an outmoded form of ethnicity was said to be the reason why Latinos did not vote. As the sociologist Felix Padilla has noted, “'We have always been thought of as another ‘minority group’ that will in time become part of the “melting pot’ in much the same way European ethnics did years before … Hispanic people will make it into the mainstream of the larger society when they agree to assimilation like other ethnic groups.”25

While social science inquiry has become more attuned to the subtleties of immigrant communities, there seems in the late 1990s to be a resurgence of the assimilationist model. This is partly a response to increased immigration to the United States in the late 1980s at a time of economic restructuring and renewed concern about the erosion of the American character. This concern echoed cries in academia by conservatives who argued that, as more minorities entered higher education and demanded a diversification of course offerings, the traditional Western European canon of knowledge was eroding.26 This debate has emerged principally as a response to the multicultural movement that sought to make public spaces more inclusive.27 In immigrant and minority communities the multicultural movement was often spurred by intellectuals responding to a public discourse, particularly as articulated in higher education curricula that excluded works and topics relevant to these communities.28 Multiculturalism was also evident as issues of identity became central in the arts. Artists, writers, and musicians played critical roles in generating new ways of viewing, hearing, and sensing a community displaced from both home and host countries.29 Yet critics maintained that in order for democracy to be sustained all members of American society need to share a common cultural base.30

In regard to Cuban exiles two celebrated studies have revived the assimilation model. Gustavo Pérez-Firmat’s Life on the Hyphen: The Cuban-American Way explores what he calls the zone of the one-and-ahalvers, those born in Cuba and raised in the United States.31 In Pérez-Firmat’s view the hyphenated phenomenon is temporary, as the children of his generation will become more fully American. David Reiff reaches the same conclusions in The Exile: Cuba in the Heart of Miami, as he follows a couple born in Cuba as they return to the island and try to make sense of their split identity.32 Reiff predicts that their son, twelve years old at the time, is the one who will become American. Reiff s overarching message to the parents is: “Why don’t you become American?” Curiously, scholars on the island also bewildered by the persistence of nationalism and interest in home country issues among exile communities have used a variant of the assimilation model to study the Cuban community in the United States.33

These models embody the assumption that identity is tied to a single nation-state and that each nation-state has a certain culture from which people either move away from if they are emigrating or move toward if they are arriving. It further assumes a fixed identity in both locations that does not change over time. Both home and host country are seen as mutually exclusive of each other and composed of “pure,” or authentic, culture. And, in the case of Cuba’s official vision, cultural identity is also a matter of “social conscience and concrete behavior toward the nation.”34 Therefore, it has both a cultural and an ideological presupposition.

Cuban Exiles and Latino Studies: Similarities and Differences

The Cuban community has evolved within a context denned by U.S.-Latin American relations. In part this is a study of how U.S. foreign policy intersects domestic reality and shapes the elements that go into making a community. While the relationship between foreign and domestic policies may be clearer in the case of Cubans than for other diaspora communities, it is nonetheless fruitful to understand it within the larger framework of U.S.Latin American relations.

While other Latino communities may not have the obvious ties that the Cuban community has to foreign policy projects, the origins of the Mexican and Puerto Rican communities in the United States can be traced to the expansion of the United States in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century U.S. policies in Central and South America have also resulted in population displacement. For instance, after the U.S.-sponsored military coup in Chile in 1972 a large number of Chileans fled to the United States, as did many Central American refugees after the covert U.S. role in regional civil wars in the 1980s. In this sense U.S. foreign policy has played a part in the formation of these immigrant communities.

Furthermore, the immigrations have been framed by economic and political factors in home and host countries that are related to the position of these countries in the world system, particularly their relationship to the United States.35 Economic and political situations—for instance, the collapse of Haiti in the late 1970s—have contributed to immigration flows and to the subsequent formation of communities in the United States. This phenomenon extends to other regions,36 but the particular historical relationship of the United States to parts of the Spanish postcolonial world in Central America and the Caribbean contributes to the commonalities that exist among immigrants from this region.

Like Cubans, other Latino communities have also had very ambivalent relationships with their homelands. Mexicans who have gone to el norte, the north, often have been portrayed as pochos (wetbacks).37 In Puerto Rico supporters of both statehood and of independence have campaigned actively to keep Puerto Ricans in the United States from voting on referenda on the future political status of the island. And, of course, the Cuban government has portrayed those who have left the island as gusanos (worms), escoria (scum), and most recently anti-Cubanos.38

Once in the United States all these communities have faced varying degrees of exclusion and racism. Even Cubans, labeled the “Golden Exiles” because of the disproportionate percentage of professionals in the earlier waves of immigrants, faced overt discrimination. Latino communities thus share the dual dilemma of rejection by their homeland and discrimination in their host country.

Nonetheless, there are important differences among Latino communities.39 While I consider the Cuban experience, like those of other Latino communities, to be one of diaspora, to understand the politics and identity of Cuban exiles requires a close examination of the notion of exile itself, since it plays such a powerful role in the community’s organization of politics and identity. The idea of exile is the thread that holds together the political memory of the community.

Exile itself is an ancient affair. Banishment has been used as punishment by many societies throughout history. It is not even an exclusively human process. Many animal kingdoms also use banishment, particularly to discard their ill and elderly, although in some species contenders for the dominant male position are also expelled upon losing their bids for power.40 For humans exile is a forced separation from the homeland, a punishment that carries with it the inability to return.41

Yet what constitutes a “forced” separation is open to debate; the definition may range from actual physical expulsion to the inability of displaced persons to find work or housing in their homeland. Generally, however, the fear of persecution is a component of the definition of exile or the status of political refugee. And the impossibility of return is a critical element of the condition of exile.

The dislocation of exile consists of physical separation from the homeland, destierro, which in turn produces a personal dislocation, or destiempo.42 The physical separation is literally a geographic relocation to a place with a different culture and often a new language. The personal dislocation includes the loss of social and personal structures that vary in significance according to the individual’s life cycle at the time of exile. Both destierro and destiempo include the loss of memory of a place.

Memory becomes a central force in creating a diasporic identity.43 The inability to reproduce the past or to return to a prior status compels the re-creation of memory of what was left behind. Myths about the past and the future play a powerful role. Memory, remembering, and re-creating become individual and collective rituals, as does forgetting. In this sense the formation of an exile community is a process similar to that of nation building, one in which collective symbols form a constellation of reference points that endow upon disparate fragments a sense of congruity.44 For communities of exiles, however, this emerging collective identity occurs despite, not because of. geography.

Exiles are outsiders in both their home and host countries. Yet they are not totally disconnected from either. The difficulty for many is not “simply being forced to live away from home, but rather, given today’s world, in living with the many reminders that you are in exile … the normal traffic of everyday contemporary life keeps you in constant but tantalizing and unfulfilled touch with the old place.”45 Meanwhile, the exile engages with the new home. But being in exile in a host country that is antagonistic to immigrants further institutionalizes a sense of isolation. Being a stranger, an outsider, creates barriers that reinforce the need to hold together the community. Removed from the familiar and now living in a hostile environment, the exiles become strangers to themselves.46

Desiring the past, and recreating that past culturally and politically, is a form of nostalgia. Nostalgia may be a common phenomenon, but for exiles this desire for the past is located in the memory of another geographic space: the homeland that embodies the past, childhood, sensuality. The nostalgia prevalent in the exile community and woven into its politics and identity reflects the impossibility of return. As opposed to yearning, or the desire for something that may be attainable, nostalgia is a desire that can never be realized.

Nostalgia contributes to the creation of a collective sense of identity and helps ease the pain of loss. By recreating a mythical past, exiles can feel that they have not completely left their place of origin. In addition, exiles hope that holding onto the past may facilitate a return to it. Nostalgia becomes a way to challenge efforts by the home country to erase the exile community from its history, as well as a means for coping with the host country’s ambivalent acceptance of the group.

The political circumstances that complicate a physical return disguise the reality that any return to the past or to childhood is impossible. Therefore, the ongoing personal negotiation between wanting to return to the past and accepting the need to go on with one’s life—a natural part of all human growth—is cast as a political issue. The personal thus becomes almost exclusively political.

While exile is most readily felt by those who leave their homeland, it also has an impact on those who stay. Massive emigration changes the landscape. It produces a loss. In a strange sort of way an exile community may in fact reinforce the borders of a nation-state. Exile entails the leaving of a country. An exile community abroad is a constant reminder that the borders still exist.

There are few studies of the politics of exiles.47 In perhaps the most extensive one Yossi Shain studied exile political organizations in order to understand the dynamics of opposition politics.48 In the era of nation-states governments relied heavily on nationalism as a means to claim legitimacy. Exile organizations trying to topple a government from abroad have been at a disadvantage in asserting political legitimacy. In addition, the spatial and temporal separation disconnects exile organizations from the quotidian realities of their homeland. Of course, the role of exile organizations in homeland politics may change in the future, as communication and economic ties between exiles and homeland increase. Moreover, in some cases, such as Cuba, the conditions of exile have lasted almost four decades. Each new wave of exiles has brought an updated vision of the island. As a result, the exile community’s vision of homeland has been replenished continually and thus is more closely aligned with the island’s reality. Yet the role of nationalism in both the building of new regimes and in the laying of claim to legitimacy is useful in understanding the Cuban experience.

For Cubans the mythology of exile and nation from afar is rooted in its own history. Since the days of Spanish colonialism exile has been used to discard challengers to the Crown. Originally, it was Spain that cast people from the “motherland.” In 1492 the Moors and Jews were expelled, and later the Jesuits were exiled from the Iberian Peninsula. During the colonial period Spain expelled supporters of independence movements from their colonies to Spain or to other colonial holdings.

Sympathizers of Cuban independence often would decide to leave the island even before they were deported. Consequently, the Cuban independence movement was conceptualized and organized in the United States. The movement of people off the island created a locus of cultural and political production in foreign lands. Feelings of nostalgia and desire are found in the works of José María Heredia as well as the poems of Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda and José Marti, each writing of homeland from abroad.49 The Cuban nation was conceived from afar.

Throughout the twentieth century Cuban emigration continued, particularly to the United States, as waves of both economic and political refugees sought a haven. While the broader movement of people from Cuba to the United States was related to the ups and downs of the cigar and sugar industries, there were also distinct political moments that created political exiles. Economic and political changes on the island contributed to a continuous flow of Cuban immigrants and political exiles to the United States. They also continued to influence the unfolding of events in the Cuban émigré community, which also grew over time.

Throughout the 1930s Cuban political émigrés sought refuge in the United States from the Gerardo Machado dictatorship. Together with progressive North Americans and other political émigrés, these exiles published an opposition newspaper in New York that they smuggled into Cuba.50 Later, in the 1950s, while temporarily out of power. Fulgencio Batista made his base in the United States. Upon his return to power his repressive regime again forced many Cubans to the United States, including Carlos Prío Socarrás, former president of Cuba. With support from Cubans living across the United States, Batista’s opponents formed committees sympathetic to the 26th of July Revolución Movement headed by Fidel Castro, who traveled through the United States raising money and support from exiles.51 Exile politics were again important to the future of Cuba. Not surprisingly, Cuban-influenced culture also flourished in the exile communities of the 1950s, giving rise to Cuban jazz, the mambo craze, and the “I Love Lucy” show.52

In the later part of the twentieth century, as exile came to be defined along the ideological fault line between communism and capitalism, the decision to remain or to leave one's homeland became even more politicized. Socialist countries set up tight restrictions on entering and leaving national territories, and political dissidents were often pushed out and forbidden to return. In turn the anticommunist West received these political refugees as heroes. The condition of exile became an ideological centerpiece of the cold war. Although the immigrant/exile duality had already been forged by the politics of Cubans in the United States since the 1800s.53 this historical dynamic now came to be defined by the sharply divided world politics of the 1950s. For Cubans who left after the 1959 revolution the exile experience was inextricably woven into historical and contemporary events.

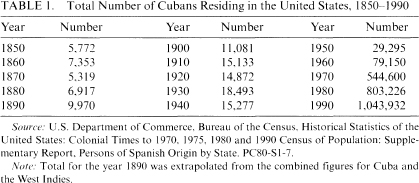

The number of Cubans living in the United States today amounts to 10 percent of Cuba’s population, with major concentrations in Florida, New York, Illinois, and California.54 Reproduction and new exiles continue to expand these communities, adding increasingly complex layers to their social and political character. As a result, the Cuban community reality is often transitional and paradoxical and does not fit easily into the traditional models through which we study émigré politics and identity. One of my goals in this book is to explore how immigrants construct their political, cultural, and personal identities in ways that go beyond what is legalized or permitted while understanding how these structures influence the options available to these communities. This question has resonance beyond the case studied here. The problematic of immigrants is not unique to the United States and Latin America; it is a vital issue for sending and receiving countries around the world.