CHAPTER 3

The 1960s: Entrance, Backlash, and Resettlement Programs

The military and political relationship between Cuban émigrés and the United States had a profound influence on the development of the exile community. The U.S.-sponsored military operations were accompanied by a series of evacuation and immigration programs that will be explored in this chapter. After the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion it became clear that the temporary exiles would be around for some time. Local reaction, which had not been uniformly supportive of the exiles in the first place, intensified and the federal government responded with a massive effort to relocate Cubans out of Miami. As refugees continued to leave Cuba. Congress worried about the lack of stringent security clearances for those entering the United States. In the midst of contradictory federal policies, negative local reactions, and increasingly heterogeneous immigration, Cuban exile communities became established throughout the United States, although Miami remained the largest center.

Entrance: The Visa Waiver Program

The movement of Cubans to the United States was first conceived as a way of evacuating U.S. agents and their families from the island and was expected to last for only a limited time. The program included granting visas and sometimes visa waivers to key figures in the underground opposition. Manuel Ray, for example, received visas from the U.S. Embassy not only for himself but also for his wife, children, and the children’s nursemaid to come to the United States.1 The same was the case for José Miró Cardona, whose departure from Cuba was a topic of correspondence between the ambassador and the State Department.2 Others received visa waivers.

Yet these extraordinary documents presented various problems. For one. the underground was afraid that Cuban security would uncover their cells if they were found to be holding visa waivers. Once in the United States people with visa waivers had no legal status. This issue was noted in a Department of State memorandum of a conversation held between a group of individuals whose names remain classified and Charles Torrey, of the Caribbean and Mexican Affairs Division, dated March 23, 1960. Among the various requests presented by the group was a plea to help the “great number of Cuban exiles in the U.S. on visitors’ visas or illegally.”3 The “visa problem” as it was referred to by State Department officials, was cause for concern. A memorandum of conversation dated November 29, 1960, entitled “Activities against the Castro Regime,” in which members of the Frente Democratico Revolucionario were present, stated that

Cuban refugees arriving in this country were most reluctant to issue strong denunciatory blasts against the Castro regime so long as their immediate families remained in Cuba. For this reason, it was frequently of great operational interest to expedite visas for family members, however it was usually very difficult if not impossible to arrange such matters. The standard answer received was that another office, another department or another agency of the United States had jurisdiction.4

The memo also records a rationale for increasing government financial assistance to refugees in Miami; it raises questions about the prevailing notion that the assistance program to Cuban refugees was conceived as a way to lure refugees to the United States:

the latter are arriving without clothing or personal effects or funds. On humanitarian grounds they must be taken care and the FDR frequently “stakes them.” This represents a strain on its funds, however, and it should be borne in mind that if other resources were made available to care for the refugees it would help to ease the drain on FDR funds and allow them to be used in more productive ways.5

This note casts doubt on the prevailing notion that U.S. government social programs were put in place as a way of luring Cuban exiles to the United States; rather, it suggests, the programs were put in place as a way of insuring that monies earmarked for military purposes were not siphoned off for family needs. It was military needs that dictated the procedures used to bring Cubans to the United States as well as the social services provided.

Children’s Visa Waiver Program

The underground’s family needs also led to another program unprecedented in U.S. immigration history. Members of the underground opposition became fearful that visa waivers given to their families, specifically children, would make them susceptible to retaliation by the Cuban government. Therefore, a special program for children of members of the underground was conceived. This became known as Operation Pedro Pan. According to James Baker, at the time headmaster of the Rustin Academy in Havana, members of the underground contacted him about securing the safe exit of their children from Cuba. He then spoke with U.S. Embassy representatives, who granted him two hundred student visas. Father Bryan Walsh, a Catholic priest in Miami who had been in charge of relocating Hungarian freedom fighters following the 1956 repression, was asked by State Department officials to take care of the children.

This method had to be abandoned, however, after the break in U.S. diplomatic relations with Cuba in 1961, for there was now no embassy to issue visas. The Swiss Embassy had taken over some of the duties of the U.S. Embassy, but not all consular activities had been transferred. At the time there was no quota for immigrants from the Western hemisphere, but Cubans still needed a visa to enter the United States, and airlines would be fined if they brought someone without documents into the United States. Some Cubans still held valid U.S. visas, but many did not. If Cubans were to receive a visa through the Swiss Embassy, they could not be interviewed by U.S. officials on the spot, as State Department security procedures required.

The quickest way out of the country was through a visa waiver program. Technically, the U.S. State Department in concurrence with the Justice Department could authorize the issuance of visa waivers for emergency evacuations.6 Two distinct visa waiver programs were set up, one for members of the underground and the other for children. Father Walsh was put in charge of the children’s program. Blanket visa waivers were issued only to children under sixteen years of age. Children between sixteen and eighteen needed clearance from the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) office in Miami and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Once in the United States children could claim their parents by applying to the State Department for their visa waiver; their parents’ security checks took three to four months. In Cuba priests and nuns played a key role in identifying the children who would participate in the program; they would submit the names to their contacts and would, on occasion, be the ones who distributed the visa waivers.

The other visa waiver program was run through the underground. The Revolutionary Council, the political organization that had replaced the Frente, had a liaison who would collect applications from relatives in Miami for people they wanted to get out of Cuba. These were then shipped to Washington. A June 1961 memorandum of conversation from the Department of State records a meeting between Dr. Carlos Piad, identified as the Washington representative of the Cuban Revolutionary Council, and Robert Hurwitch, of the State Department, attesting to this arrangement.7 But not all council members were happy with the system; they claimed that they needed a neutral liaison, not one who was allied to any particular organization. After this development Tony de Varona, one of the directors of the council, named Wendell Rollason to deal with the waivers. Rollason, the director of a local Miami organization that had been helping Latin American refugees, had been contacted by State Department officials to help with the visa waiver program.8 Robert Hurwitch wrote to Varona, “we would prefer that all matters regarding visa waivers of interest to the Council be forwarded to this office by one person in order to administer the Council’s requests most efficiently.”9 In effect both programs gave a private individual the authority to grant visa waivers. There is no historical precedent for such an arrangement.

Massive Exodus: Propaganda Coup

While the origins of the visa waiver programs were in the underground and military operations, they gained a life of their own as the rush to get out of Cuba continued to grow. In addition, refugees fleeing communism had a symbolic value for the United States. The reasons can be found in the foreign policy objectives of the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, which included the need to show the failure of the Cuban revolution.10 Consider the case of the former president of the Cuban Supreme Court, Emilio Menéndez, as reported in a Department of State telegram on December 19, 1960:

Dr. Menéndez wishes to remain in U.S. with family which reportedly is now there. Given his prominence and decision to break with Castro regime for reasons specified in his letter of resignation, Embassy believes it is in our national interest to allow him to stay in the U.S.11

The ideological campaign against the Cuban revolution had begun early and the political discourse of the time was cast in the anticommunist language of the 1950s. A good representation of this discourse is found in a State Department document released days before the Bay of Pigs invasion. The themes that run through the report include the betrayal of the middle class by the revolution, the establishment of a communist beachhead in the Western hemisphere, the delivery of the revolution to the Sino-Soviet bloc, and the assault on the hemisphere.12

For U.S. policymakers the strongest evidence of the betrayal of the revolution and its failure to live up to democratic ideals was the emigration of thousands of Cubans, particularly those from the middle class. The much-used phrase “voting with your feet” reflected the vision of many policymakers; as one congressional representative said, “Every refugee who comes out [of Cuba] is a vote for our society and a vote against their society.”13 In particular, massive migration of professionals proved to the world that the revolution was failing and, more specifically, was betraying the middle class.14

In 1960 President Eisenhower approved funds to help Cuban refugees arriving in the United States. He named Tracy Voorhees to head a presidential commission on Cuban refugees (earlier Voorhees had coordinated the president’s Hungarian refugee program). Funds were allocated for a host of refugee activities through the president’s Mutual Security Fund. Days after taking office, John F. Kennedy continued this program and ordered Abraham Ribicoff, secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), to direct Cuban refugee activities. The memo to this effect read:

I want you to make concrete my concern and sympathy for those who have been forced from their homes in Cuba, and assure them that we will expedite their voluntary return as soon as conditions there facilitate that … Here and abroad, I want to re-emphasize most strongly the tradition of the United States as a humanitarian sanctuary … [The United States] has extended its hand and material help to those who are exiles for conscience’s sake.15

At this time the refugee program was still conceived as temporary. On February 2, 1961. the day after Ribicoff assumed his new post, he reported to the president. “The flight from the oppression and tyranny of the Castro regime by large numbers of Cuban people to the United States is stirring testimony to their faith in the determination of the Americas to preserve freedom and justice.”16 Ribicoff asked that an additional four million dollars be allocated to augment the one million that had been authorized by Eisenhower the previous month.

Congress was also aware of the ideological value of the Cuban refugees. In the summer of 1961 the House Committee on the Judiciary held hearings on a bill to amend the Immigration Act of July 1960 to enable the executive branch to resettle certain refugees. Included in the amendments was a section authorizing the president to allocate monies for the resettlement of refugees from communist-dominated or communist-occupied areas. The president’s letter to the committee made specific reference to Cuban refugees. Secretary Ribicoff also made an appeal for more funds and reported that, among other programs, to date more than $500,000 had been spent to resettle seven hundred unaccompanied Cuban children. Roger Jones, deputy undersecretary of state, explained the rationale for the request to extend the refugee programs and amend the language of the enabling legislation: “Programs under review by this committee could be fully justified on a humanitarian basis alone, all the programs are of utmost importance to our foreign policy in terms of their economic, social, political and spiritual significance.”17

Backlash: Shutting the Doors

While congressional committees seemed friendly to the overall thrust of the resettlement program, there were many concerns. Some representatives questioned whether or not the refugees were economic rather than political migrants. More disturbing to Congress was the method of entrance into the United States and the status of those already here. According to James Hennessy, executive assistant to the Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization of the Department of Justice, as of July 31, 1961, there were 65,700 Cubans in the United States apart from permanent residents. Of these, 24,000 were nonimmigrants admitted for temporary periods; 41,700 were classified as refugees, of which 4,500 were parolees; and 37,200 were originally of nonimmigrant status and had overstayed their visas. In other words, there had been little control of who and how people had entered.

When asked about the screening procedures for those granted visa waivers, Hennessy refused to answer but said he would do so under executive session, since the screening procedures were supposed to be secret. Hennessy went on to confirm that before the State Department granted a visa waiver the name of the person was checked against the CIA’s Caribbean index to see if he or she was a subversive and the name was then sent to the FBI and the CIA. In 1961, 30,000 visa waivers had been issued. Several members of the committee were extremely concerned about the security measures taken to insure that Cubans receiving the waivers were checked. The problem was that there was no U.S. Embassy in Havana, and the files normally kept by embassies include background information on people who apply for tourist visas.18

A few months later, in December 1961, a subcommittee of the Senate’s Committee on the Judiciary met to investigate problems connected with refugees and escapees. This time the visa waiver program is described as follows:

Visa waiver is an emergency procedure for persons traveling direct from Cuba to the United States. The beneficiaries of this action have been primarily parents, spouses and minor children of persons already in the United States; Cuban children coming to the United States for study, either supported by their parents or sponsored by the voluntary agencies; and visitors for urgent and legitimate business or personal affairs. Waivers have also been approved for a limited number of persons not meeting the above criteria, whose cases involve overriding factors of compassion accepted as justifying emergency action.19

But the senators, like the representatives, were also concerned about security procedures. Hennessy updated the number of visa waivers issued, which by the end of 1961 numbered more than 80,000. By December 20,000 of these had been used.

Those involved in the visa waiver programs made strong appeals to Congress that the program continue, arguing that the programs represented an important weapon in the ideological fight between communism and freedom. The unaccompanied children’s program was a key focus of the testimony of Wendell Rollason, at the time director of the Interamerican Affairs Commission in Miami and the person named as liaison to the State Department on matters pertaining to visa waivers: “The visa waiver program … is the very lifeblood of the average Cuban in his hopes and plans to escape the ravages of communism.” He went on to recommend that the visa waiver program be continued.20 Father Bryan Walsh, who had been granted the authority to issue visa waivers to children and was their principal caretaker once in the United States, testified about the unaccompanied children’s program but asked that the number of unaccompanied Cuban children be kept secret out of fear that the Cuban government would decide to shut off the supply of exit visas.21

The visa waiver program ran until October 1962, when, days before the missile crisis, the Cuban government canceled all flights leaving or entering the island. On the U.S. side, instead of fomenting emigration to show the world that people wanted to flee communism, the State Department now wanted to put enough pressure on the island to create an internal uprising. An air isolation campaign was put in place to insure that missiles could not be brought onto the island. At the time many families were divided, with about six thousand unaccompanied children waiting in the United States for their parents.

In 1963 the Senate’s Committee on the Judiciary heard the testimony of Dr. Ellen Winston, commissioner of Welfare Administration for HEW, who asked that the State Department give priority for immigration to parents of the unaccompanied children. Cubans were transported back to the United States on the ships that had taken medicine and food to Cuba in exchange for the Bay of Pigs prisoners. HEW succeeded in getting the State Department to include 200 parents of unaccompanied Cuban children among the 750 Cubans aboard these cargo ships. The director of the Cuban Refugee Program was asked by the Senate committee if the Cuban government had helped in this request, and he answered yes.

Security concerns were echoed in House hearings on June 27, 1963. Mario Noto, associate INS commissioner, testified about the security procedures in place, but part of his discussion centered on how information about incoming refugees was collected.22 There was controversy regarding the Cuban committee that screened visa waiver applicants, since a former expert on communist activities for Batista was part of the committee’s staff, and many felt that he tried to exclude refugees who had opposed Batista.

A new and more restrictive U.S. policy was reiterated by the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson after Kennedy’s assassination. “Since July 1, 1963 … we have discouraged an influx of Cuban refugees. The crowded and potentially explosive situation in Miami and the pursuit of our isolation policy have counseled against further substantial inflow.”23

Negotiations between the United States and Cuba were initiated when the Swiss ambassador to Cuba offered to talk to the Cuban authorities on the United States’ behalf about exit visas for parents of children in the United States and to pay for flights out of Havana. In these negotiations Cuba offered to allow refugees to visit Cuba. But the State Department refused both the entrance of Cuban exiles and refugee visits to the island on the grounds that it was more important to keep Cuba isolated than to resolve the problem of the unaccompanied children.

Cuba’s response to the lack of emigration channels was to invite exiles in the United States to come pick up their relatives. On October 10, 1965, the port of Camarioca, near Varadero Beach, was opened. Within weeks more than 5,000 Cuban refugees had been transported to the United States in scores of exile-manned boats traversing the Florida Straits. Another 200,000 were estimated to be ready to leave before the exodus was abruptly cut short because of U.S. security concerns surrounding the Soviet missile crisis. The severity of the situation had forced the United States to negotiate an agreement with the Cuban government, finalized in a memorandum of understanding signed on November 6, 1965. The agreement called for the orderly movement of Cuban refugees to the United States. The Cuban government would give exit permits to those wishing to leave the island, while the United States would transport and accept the refugees. Two daily flights from Varadero to Miami were set up. By the time these “Freedom Flights” were canceled, in April 1973, more than 260,561 Cubans had used them as a way to come to the United States.

An estimated two billion dollars was spent on the refugee program, including the unaccompanied minors component.24 The U.S. government had expected that the Cubans’ stay on U.S. soil would be temporary. As it became clear that this was not the case, other programs designed to ease integration into the United States were established, such as a scholarship fund supported by HEW to help Cubans pay for college education. Unlike that of other Latin American immigrants, the entry and settlement of Cubans into North American society was greatly facilitated by the U.S. government. The high political currency attached to the flight from communism meant that it paid to be a political refugee.25

For the U.S. government Cuban émigrés provided the rationale for continuing a foreign policy aimed at containing communism and expanding the forces needed for battle.26 For the Cuban government the Cuban exodus to the United States helped consolidate the revolution politically by externalizing dissent and rendering it impotent.27 By encouraging the flow of Cuban refugees into the United States and supporting them once they arrived, the U.S. government inadvertently helped facilitate the formation of a more politically pliable population on the island.28

Local Reactions and the Relocation Movement

Upon arriving in Miami, Cubans were required to register at the Refugee Center that had been set up by the federal government in 1961. “El Refugio” provided social services, including food packages consisting of dried milk and eggs, peanut butter, oil, and Spam. Many new émigrés lived in the homes of relatives who had arrived before them. Family outings consisted of a day at the beach and a stop at a Royal Castles fast food restaurant, which ran a Sunday night special of ten hamburgers for a dollar. Children went to public schools, which, although overcrowded, quickly set up bilingual programs. The initial expectation was that everyone would be back on the island soon or at least by the following year. As time wore on, these hopes gave way to the reality of living and raising families in the United States and facing the discrimination that appeared when local residents realized the Cubans were here to stay.

In contrast to the popular image of Cubans being welcomed to the United States with open arms, an examination of the reaction to the influx in Miami indicates that some Americans were extremely leery about the arrival of Cuban exiles. The area’s residents shared some of the same fears expressed by congressional representatives. Local officials such as Arthur Patten, Dade County commissioner, stated to Congress that the “large influx of Cuban refugees presented a threat to the local balance of power, particularly if they were thinking of voting.” He testified that his constituents were fearful of the “changing complexion of the City of Miami.”29

Throughout the United States, and in South Florida in particular, Cubans were not always welcome. It was not uncommon in the early 1960s, for instance, to see “For Rent” signs in Miami that read “No Children, No Pets, No Cubans.” Unlike federal policy that seemingly encouraged migration, local and state governments and communities often rejected Cuban exiles, particularly when it was clear that they were in the United States to stay.

Local authorities in Miami effectively pressured the federal government to begin dispersing Cubans throughout the United States.30 The same concept of relocation that had been used to alleviate overcrowding in the children’s camps was extended to adults. Parents of unaccompanied children were flown to the States and reunited with their children outside of Miami. (About half the children who had come to the United States through Operation Pedro Pan were reunited with their parents.) My own parents came four months after I arrived in Miami. We were moved to Cleveland, Ohio.

One of the stated goals of the Cuban Refugee Program was to relocate Cubans out of Florida. The resettlement was done by private organizations—the U.S. Catholic Conference. Church World Service, the United HIAS Service, and the International Rescue Committee. These four organizations insured that social service organizations representing diverse religions were involved in the resettlement effort. Also involved were the four organizations that had overseen the unaccompanied children’s program. Refugees’ transportation to relocation sites was paid for, and, once relocated, refugees received help from these agencies in finding housing and jobs for the head of household.31 By 1978, 300,232 persons had been resettled.32 The resettlement program was the means by which Cubans were dispersed throughout the United States.

Golden Exiles?

The Cuban exile community has been shaped by its internal dynamics as well as by the host society’s reaction to it. U.S. and Cuban policies combined to create the Cuban exile, but sectors within the community soon began to articulate their own interests. Initially, among other things, the Cuban community in the United States had an overrepresentation of elite groups that had been overthrown on the island. This fragmented elite was composed of many sectors, including landowners, financiers, professionals, and small business owners. A disproportionate number of these elites left after the revolution, bringing with them experience, knowledge, habits, and. in many cases, social relationships that over time were replicated within North American society. As the exile community matured, it developed its own economic and political interests, such as participation in U.S. political organizations and defense of the use of Spanish in Miami.

Professionals and skilled workers were overrepresented in the first wave of exiles. Yet. even by 1961, following the Bay of Pigs invasion and prior to the missile crisis. Cuban immigrants were more heterogeneous and included many nonprofessionals, such as clerical workers.33 From 1962 to 1965 illegal entrants from Cuba were predominantly male skilled and semiskilled workers.

After 1965 the socioeconomic characteristics of Cuban émigrés changed again, becoming even more heterogeneous as a result of political repression and economic crisis on the island. Those leaving had increasingly diverse occupational backgrounds; included were many nonprofessionals, such as mechanics and farmers. In addition, people residing outside the Havana metropolitan area now joined the exodus, resulting in greater regional representation. Women and children were overrepresented among those headed for the United States, at least in part because of Cuban restrictions forbidding males of military age to emigrate.34

In 1973 National Geographic heralded those “amazing Cubans” for turning their skills into prosperity within years of their arrival in the United States.35 But, contrary to the popular image of the “golden exile,” the fortunes of Cuban exiles were mixed.36 Studies indicated that most Cuban émigrés experienced a downturn in their occupational status after moving to the United States. While many professionals, such as doctors, were able to transfer their skills readily, others, such as public administrators, lawyers, and even some scientists, could not make the same adjustment. As such, there was a tremendous loss of human capital for Cubans in the United States. Even those who were able to transfer their skills declined in social position. While faring relatively better than other Latinos, they nevertheless did not maintain the standing in U.S. society that they had held in Cuba. They were no longer their country’s elite but, rather, were part of one of the United States’s many immigrant communities.

Cubans have attained higher educational and income levels than other Latinos, but they have lagged behind the average white family. The incorporation of Cuban women into the labor force was also much higher than that of all women, and, as such, Cuban family income statistics were inflated.37 In addition, female labor force participation changed the nature of family and its economy.38 While work was available in Miami, it was often in low-paying, dead-end jobs with few benefits. And, indeed, the presence of a strong Cuban-based economy may lure the second generation away from their studies and into Cuban-owned businesses.

Although Cuban exiles of the early 1960s experienced a net decline in their economic and social position after coming to the United States, they eventually built an impressive economic base in Miami and other cities.39 The growth of what has come to be known as the Cuban enclave economy has many roots. Some scholars have focused on the close match between the kinds of jobs available in the United States, particularly South Florida, and the labor and educational experience of the immigrants.40 Others have emphasized the complex of skills and attitudes present in the first wave of exiles.41 Yet it is undeniable that much of the economic health of the Cuban exile community was facilitated by U.S. government grants extended to émigrés in the context of the cold war. Given the secrecy of these operations, it is difficult to determine how much of the money the CIA poured into Miami was actually used to set up “front” businesses or to sustain families while the men were fighting. But it did change the economic landscape; for instance, years later local Anglo business owners complained to the government that they had been displaced by CIA-funded businesses. When the federal government responded that such businesses had not been set up to make money, local businesspeople responded that this was precisely the problem. They could not compete effectively with a business that did not have to worry about making a profit.

Scholars of the late 1960s noted the self-employment patterns of the enclave economy and how social networks aided in its expansion.42 While the enclave provided jobs and a familiar cultural milieu, its success rested in part on the ability to extract cheap labor from Cuban workers. The ideological glue that cemented the enclave was the fight against Castro. Not only were émigré political organizations involved in opposition to the Cuban regime; they also exerted control over workers within the enclave.43 The hegemony within the Cuban émigré community of its most intransigent forces can be traced back to early anti-Castro activities. These conservative elements had an uneasy relationship with the more liberal-minded parts of the opposition,44 which, once defeated, lost credibility and consequently their standing in the ideological matrix of the community.45 As a result, institutionalized political power that emerged in the first instance from a connection with state foreign policies also helped generate ethnic capital.

Despite their economic successes, Cubans still faced overt racial and cultural discrimination. Cuban exiles spoke a different language, and those who did learn English generally spoke with an accent. Exiles also had distinct cultural values, particularly concerning family relations and sexuality, that clashed with those prevalent in the United States. These elements combined to isolate Cuban exiles from mainstream society.

Middle-class Cubans and professionals were thrust into associations and institutions that in the South in particular had been almost exclusively white. The entrance into society of large numbers of people perceived to be nonwhite (even though most Cuban exiles at the time were “white” in the context of their homeland) heightened a backlash against Cubans. The experience of being a privileged exile and unwanted immigrant at the same time engendered a contradictory status for Cubans in the United States. The results were twofold: a heightened sense of nationalism and a distinct U.S. minority experience.

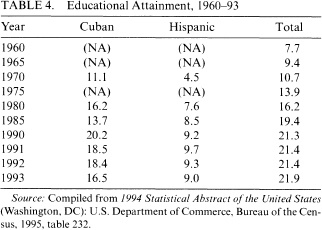

While Cuban exiles have not faced the kind of historical discrimination experienced by other Latino and minority communities, discrimination has been felt strongly. This may in fact be due to the class and education background of the émigrés themselves. A study of male Cuban émigrés in the late 1970s, for example, found that the higher the educational level the more discrimination was felt (see table 4).46

These findings are consistent with similar analyses of the experiences of the Mexican-American middle class in the Southwest, which show that questions of identity, particularly language issues, are mainly the concerns of the middle class; it is this sector of minority communities that is pressured most strongly to conform to the dominant society.47 This may be due to their greater contact with the majority population, or it may be that their perception of discrimination is heightened. Whatever the case, Cubans, like other Latinos, enter a “racialized” political environment in which they are perceived to be nonwhite by the dominant culture, regardless of how they define themselves racially.

Exile Politics and Identity

Exile politics emerged from two contradictory realities. In the early 1960s exiles shared the strategic political goal of overthrowing the revolution—a goal that coincided with U.S. policy at the time. But this strategic uniformity obscured the ideological pluralism that characterized the opposition.48 Early exile politics was extremely diverse. The opponents of the revolution were not only ultra-Right landowners and business people but also students and religious activists. Adherents of many political tendencies encompassed the exile body politic, including social and Christian Democrats. But the political culture in which politics unfolded had little tolerance for dissent. In addition, infighting and power struggles contributed to deep divisions within the émigré community. A study entitled “Cuban Unity against Castro” undertaken by a special committee of the Justices of the Cuban Supreme Court noted that in 1962 there were two hundred anti-Castro organizations in exile: “The multiplicity of the exile groups reflects the division and disunity among them. A further complicating factor is the gulf that exists between groups in exile and anti-Castro elements within Cuba.”49

The Cuban Revolutionary Council, which split after the failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion, was an example of this disunity. Manuel Ray went on to form his own organization in Puerto Rico called Junta Revolucionaria. El Directorio Estudiantil broke off from the other groups. And a debate was waged among other members of the council as to the legal path of succession after Castro’s fall. One group advocated a “presidential restoration formula” that called for restoring Carlos Prío Socarrás, the nation’s last popularly elected president. Another group called for a “constitutional formula” based on a provision in the Cuban Constitution of 1940 providing that a Supreme Court Justice be appointed provisional president until elections could be held.50 Their preferred candidate for president. Julio Garceran, had been chastised strongly by the Department of State for declaring that he had been chosen president of the Government of Cuba in Arms in Exile.51

Other groups fought in the underground. Tony Varona’s group, Rescate, continued fighting in Cuba until its members were arrested and jailed in 1965. Among those organizations that continued to fight in the Escambray Mountains in Cuba were El Segundo Frente del Escambray, headed by Eloy Gutierrez Menoyo. who would become a leading spokesman for a reconciliation with the Cuban government, and the Insurrectional Revolutionary Movement headed by Dr. Orlando Bosch, who would later be hunted by the FBI as a terrorist for his participation in the bombing of a Cubana airline in which over two hundred Cuban athletes died.

Independent action by groups opposed to Castro was strongly discouraged by the United States. For instance, in 1963 a coalition of exile organizations proposed a referendum to choose leaders for the continued struggle against Fidel Castro. Promoted by Pepin Bosch, owner of the famous Bacardi Rum Company, the referendum aimed to “create a Cuban representation in Exile to make efforts to attain the liberty of Cuba” and also to “propitiate the integration of efforts and wills of all Cubans and all organizations pursuing the same patriotic goal of liberating our country.”52 The leading candidates included Erneido Oliva, a veteran of the Bay of Pigs invasion; Ernesto Freyre, secretary of the Cuban Families Committee, which helped negotiate the release of the Bay of Pigs prisoners; labor leader Vincente Rubeira; Aurelio Fernandez, accountant and former member of El Movimiento Recuperacion Revolucionaria; and Jorge Más Canosa, a former law student in Cuba who had fought against Batista and later against Castro. Más Canosa would go on to become the most powerful Cuban exile leader in the 1980s.

The U.S. government opposed the referendum. The State Department Office of the Coordinator of Cuban Affairs in Miami referred to the group as an “undistinguished five-man slate.”53 A note attached to a report sent to Robert Kennedy summarizes the positions of various agencies within the U.S. government: “CIA opposes the referendum. Crimmins says State is neutral on the referendum … probably not possible, very expensive and not necessarily a good idea if it could be done.”54

From then until 1965, the year the Cuban government defeated the internal counterrevolution, several exile groups led raids on the Cuban coast, smuggled arms and newspapers into Cuba. Robert Kennedy was now in charge of Cuban policy. General Edward Lansdale, CIA agent and real life character on which the novel the Ugly American is based, ran the day-to-day operations. The project was code named Operation Mongoose and included some of the more notorious attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro.55 Exile groups maintained an active fund-raising drive among Cubans in the United States. Fund-raising was frequently accomplished through extortion and threats; workers implicitly understood that their jobs depended on their contributions.56

By 1965 there were more than twenty thousand political prisoners on the island.57 Despite increased repression in Cuba, these years brought a general depoliticization of Cuba among the exile community. The concerns of daily life began to preoccupy the exiles, and returning to Cuba became a distant dream. As a result, military activities seemed out of place in the politics of the community and found expression, instead, in underground military organizations.58 The void created by the lack of legitimate political activity sparked an opportunity for different political tendencies to reemerge.

Exile political identity developed in parallel to these various phases. As long as there was a possibility of returning to Cuba, those who left identified themselves as citizens of the island and temporary visitors to the United States. From the beginning of the revolution almost everyone, refugees and U.S. policymakers alike, had anticipated that Cuban exiles were only in the United States for the short time it would take for the Cuban revolution and Castro to fall. The legal status of Cuban exiles was uncertain because many had entered on visa waivers. Eventually, they were afforded the temporary category of “parolees.”

By 1965 the revolutionary government in Havana was in firm control of the island, and it was becoming uncertain whether Cuban exiles in the United States would ever return to Cuba. The practice of granting blanket political asylum to all refugees added to the émigré community’s sense of exile. As time passed and the possibility of return faded, exile identity became more of a political statement.

In 1966 Congress passed the Cuban Adjustment Act, allowing Cuban refugees to become legal U.S. residents upon a petition for asylum. This act in effect acknowledged the end of the promise of returning to Cuba. The refugee program for Cubans continued, as local governments complained of the strain that these new immigrants were placing upon their cities. The program included benefits such as food and cash allotments that were not extended to local residents, thereby sparking tensions between native residents and incoming refugees. African-Americans, in particular, were angered that the federal government would aid refugees from another country yet not assist those of their own community.

Two flights a day arrived from Varadero. But these refugees, much like earlier waves, were not uniformly welcomed. Petitions and letters of protest poured into the Johnson White House. Citizens like Barbara Fallon exclaimed: “The world is laughing at us again, Mr. President… Flagler Street has become the main street of Havana … Where is our policy to ‘offer solace to refugees from Communist-held governments’ to stop?"’ Therese Muller. a ninth-grader whose father had decided to leave Miami, wrote to President Johnson: “sir. you don’t know what’s it like. Every where you go all you can here is Spanish … I have had my fill of Cubans.” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) wrote, “we are in favor of our national policy of admitting the oppressed of the Castro regime … however, the Federal government must exercise its responsibility toward the economically oppressed of this community.” And John Holland, a Los Angeles City councilman warned, “very dangerous decision … we may get trained agitators and saboteurs.”59

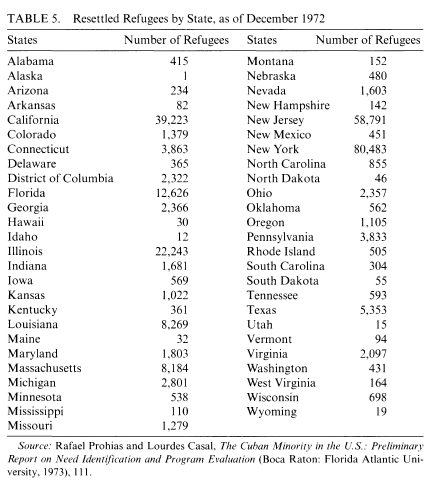

Despite community opposition. President Johnson put his full weight behind the relocation program. The program, initially designed for unaccompanied children and later extended to families, was reinstated. Through a series of private social service agency initiatives the government continued to lure Cubans from Miami to other parts of the country. The Catholic Church, through its social service arm. Catholic Charities, played a key role in these efforts. As a result, during the late 1960s and early 1970s Cuban communities emerged and grew in New York, New Jersey, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and parts of Texas (see table 5).

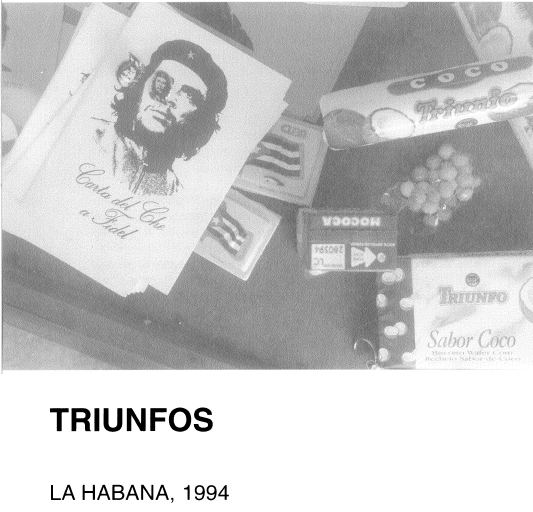

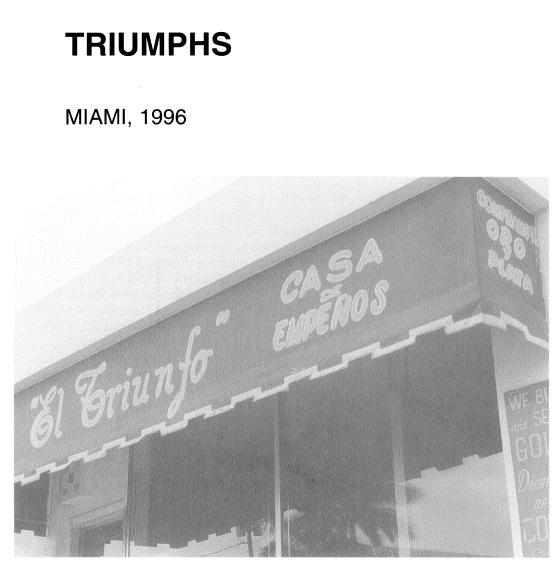

Despite the anti-Cuban backlash—or perhaps because of it—émigrés did maintain a sense of “Cuban-ness” through newspapers, professional and cultural associations, and, for those outside of Florida, yearly visits to Miami.60 Cubans already adept at combining various cultures into one continued their Cuban cultural practices at the same time that they lived in the United States. But these cultural practices tended to be frozen in time. Little Havana tried to replicate Old Havana down to the names of restaurants and social and professional organizations. News and political messages were transmitted through small newspapers and eventually radio stations. These came to be known as the “firing squads of el exilio” as anyone with a point of view that departed from the official exile ideology became the target of virulent radio personalities.

Cubans in las colonias del norte (the northern colonies) constructed tightly woven social and political communities even as they adapted to new challenges. For instance, Cuban émigrés in Detroit invented a contraption for roasting pigs in the snow so that the typical Christmas Eve meal could be served. Yet, unlike Miami’s enclave, Cubans living in the North had to negotiate their politics and identity in the context of other emerging Latino communities. They were some of the first to witness the urban unrest of the late 1960s. Unlike the placid and patriotic early 1960s, the middle of the decade witnessed major transformations in U.S. society, including the rise of the antiwar and civil rights movements that mobilized African-American and Latino communities across the country. Because these movements demanded equality for all, the special treatment given to Cuban refugees was a sore point for many. For example, black leaders in Miami lodged formal complaints with the Johnson administration, insisting that they receive the same benefits given to newly arrived Cubans.

In regard to the island, however, the Johnson administration continued Kennedy’s policy. Its main objective was “the replacement of the present government in Cuba by one fully compatible with the goals of the United States.”61 The plans included the utilization of anti-Castro Cuban exiles to provide deniability of U.S. involvement. The CIA continued planning and carrying out acts of sabotage against Cuba. There were those more willing, however, to take another route. For instance, Gordon Chase, a White House advisor to the president, did not rule out that Castro could be convinced of breaking ties with the Soviet Union.62

In 1968 Richard M. Nixon was elected president. His close ties with Cuban figures such as Bebe Rebozo helped refuel the covert war against the Castro regime.63 But increased public condemnation of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam limited these activities. Toward the end of the Nixon administration some U.S. policymakers and elected officials advocated a relaxation of tensions with Cuba. Terrorist acts against governments that had economic relations with the island became more frequent. Doubts about U.S. policy in Cuba grew when covert activities against the island’s government began to have domestic implications in the United States. Among other things the Watergate burglars were Cuban exiles, veterans of covert activities against the Castro regime.

Terrorism as a form of activism became ingrained in the political life of the exile community. Having gained control of the Miami media, many businesses, and the electoral arena, hard-line exile forces sought to impose a single, rigid anti-Castro viewpoint, using intimidation and violence to silence their opponents. Ironically, those opposed to the intransigence of the revolutionary leadership ended up creating organizations and a political environment that mirrored the island’s. While continuing a historical tradition of a dual immigrant/exile identity, the postrevolutionary émigré community developed distinct characteristics that, despite its origins in a struggle to restore the democratic course, are rooted in the larger world drama of the cold war. Despite unresolved questions about the place of Cubans in U.S. society, the 1970 U.S. census reported that there were 560,628 Cubans in the United States and that 252,520 lived in Florida. The community was now firmly ensconced in its host country.