CHAPTER 6

Cuban Exile Politics at the End of the Cold War

The end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s witnessed major transformations globally. The cold war that had so definitively shaped world politics since World War II came to an end. The end of the cold war did not automatically translate into changes in U.S. policies toward Cuba. It did, however, mean that Cuba as the world had known it ceased to exist. No longer a favorite trading partner of the vanishing socialist bloc, it was left on its own to survive. As such, its economic and ideological apparatus began to crumble.

A tremendous power struggle ensued on the island that within a period of three years had given way to extensive political purges. One arena within which these power struggles took place concerned Cuba’s policies toward its communities abroad. Policies toward the émigré community became entangled in internal bureaucratic power politics. At the same time, emigration off the island increased dramatically as economic conditions worsened and political opportunities for change dwindled. This provided the weakening government with an issue through which to rally el pueblo and a trump card with which to negotiate with the United States.

Meanwhile, in the Cuban exile community an unprecedented realignment occurred as dissidents from the Right and Left coalesced into a new force searching for alternatives within the post-cold war context. Former activists from the Cuban-American National Foundation and the Antonio Maceo Brigade began to talk to one another about the need for a more comprehensive view of the nation and exile. Intellectuals and artists who left the island in the late 1980s and early 1990s enhanced the conversation. At the same time, a discussion of Cuba’s future and its relationship to the community abroad was also taking place across the Florida Straits in Cuba.

Waiting for the Fall

Ironically, Ronald Reagan’s term in office closed with the United States and Cuba signaling each other about a possible resolution to their conflicts. A thaw in relations between the Soviet Union and the United States facilitated the administration’s reconsideration of its Cuba policies. The most visible sign of this thaw was the reinstatement of the 1984 immigration agreement that had been canceled by Cuba after the United States launched Radio Martí.

The more relaxed political environment in the White House created a climate in which the notion of reengagement could surface in the legislative branch as well. In 1988 Senator Claiborne Pell, Democrat from Rhode Island and chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, presented to Congress a report from a fact-finding trip to the island urging that the United States reinstate relations with Cuba.1 The report outlined steps that could be taken to begin the process, such as drug trafficking treaties and initiatives to facilitate contact between divided families. These last issues were important in convincing moderates from the exile community to support reestablishment of relations with their homeland.

Yet voices arguing for reengagement with Cuba fell on the deaf ears of George Bush’s presidential campaign staff. Although Bush, then vice president and running to succeed Reagan, had made promises not to use an economic embargo in foreign policy disputes, he maintained a relatively hard line toward Cuba and supported the continuation of the embargo on the island. Bush also made human rights in Cuba a cornerstone of his concerns, naming Armando Valladeres. a former political prisoner, as a personal hero during televised debates. Valladeres, who spent twenty-two years in Cuban prisons, had been released in 1982 after an intensive international campaign. More militant anti-Castro Cuban exile organizations rallied around Valladeres, who eventually published several books about his experience in jail. He also established a foundation to aid Cubans who wanted to leave the island.2

Regardless of the campaign rhetoric, many observers expected Bush to engage the Castro government in negotiations once in office. They believed that, since the end of the cold war had resolved the major points of contention between the two countries. Bush would naturally seize the opportunity to chart a new course—after all, U.S. businesses were growing increasingly anxious about being denied economic opportunities on the island.3 The debate had shifted ground from whether to reengage to how to reengage.4 The Santa Fe group that eight years earlier had argued against normalizing relations now said that the fall of Castro was imminent and that the United States should get its foot in the door if it wanted to influence the future of Cuban society. In its 1988 report it advocated developing relations with younger government functionaries as a way to identify potential reformers.

Hope for a change in U.S. policy toward Cuba grew whenever the Bush administration reached out to Latin American countries through, for example, the new president’s special effort to negotiate a trade treaty with Mexico. Yet U.S. policy on Cuba remained frozen. In the spring of 1989 Secretary of State James Baker sent a memo to U.S. embassies around the world dashing all hopes that there was about to be a change. Baker said there would be no shift in policy as long as there were human rights violations and a lack of democratic freedoms in Cuba. Bush named Valladares, who had close ties to CANF, as U.S. representative to the United Nations Human Rights Commission and continued to exert pressure on Cuba through international agencies, particularly those focused on human rights violations.

Policymakers opposed to any change in the U.S. approach toward Cuba received new impetus with the fall of the socialist bloc in 1989. That year at a congressional hearing chaired by Representative George Crockett, Democrat from Michigan and head of the Western Hemisphere subcommittee of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Pamela Falk, professor at Columbia University and conservative Cuba expert, argued that a shift in U.S. policy would send the wrong message to Fidel Castro. She argued that Castro’s time was running out and that this was not the moment to take the pressure off; instead, continued pressure would help hasten the regime’s demise. Others concurred, arguing that the United States should not make changes that could be interpreted as endorsements of the Castro regime.

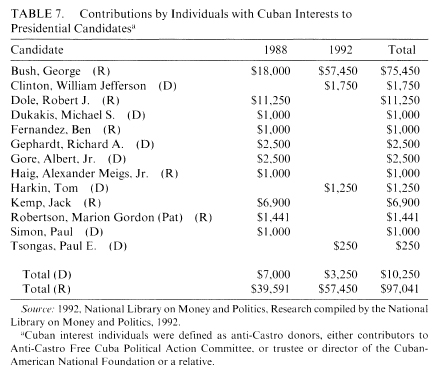

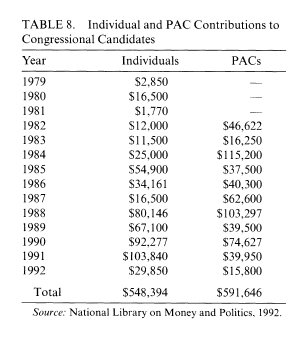

Closely linked to the endorsement of the long-standing hostile U.S. policy toward Cuba was a proposal for the creation of a television station to beam programs to the island. Modeled on Radio Martí, TV Marti would broadcast U.S.-based television programming through a newly created channel.5 There were many opponents of this proposal, even among those who had supported the radio station. They argued that Cuba could block television signals more effectively than radio waves and that, since the Cuban government had learned to live with Radio Martí, it was best not to rock the boat with a new offensive. Instead, more funding should go to Radio Martí. Ernesto Betancourt, the director of Radio Martí, supported this position, but CANF’s leader, Jorge Más Canosa, insisted on TV Marti. Congress finally endorsed the initiative, and Betancourt resigned. CANF, however, demonstrated that it knew how to play the legislative game. They concentrated their efforts in Congress and with the help of donations influenced the legislative process (see tables 7 and 8).

Other legislative attempts to toughen U.S. policy failed initially. In fact, Congress passed an amendment to the Trading with the Enemy Act that prohibited the president from directly or indirectly regulating the import of publications, films, posters, phonograph records, photographs, microfilm, and other informational material. In this way the nearly thirty-year-old ban on the importation of informational materials from Cuba was lifted.6

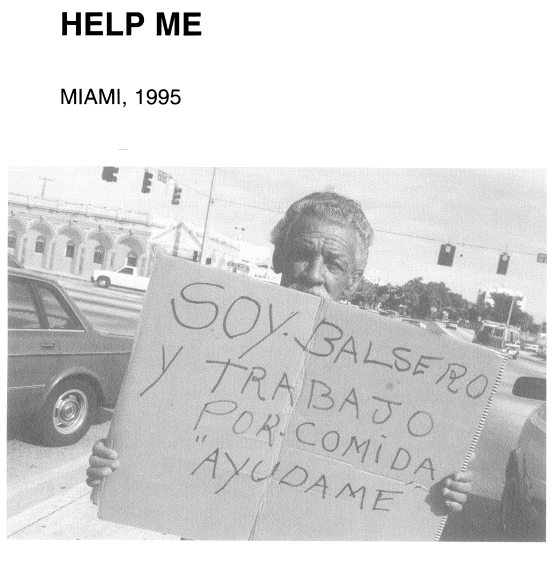

Immigration remained an area in which the administration strove to keep lines of communication open. Although the immigration treaty reinstated in 1987 was in effect during Bush’s term, many Cubans who did not qualify for the U.S. quota continued coming to the United States on rafts.7 Upon arriving in the United States, these refugees were treated as heroes by the Cuban exile community and by U.S. officials.

Estimates of those who died trying to cross the Florida Straits ranged from three in ten to seven in ten. An organization emerged called Hermanos al Rescate (Brothers to the Rescue), a group of pilots who flew over the waters of the Florida Straits in helicopters and small planes, sighting rafters and alerting the Coast Guard, who would then rescue the rafters. As the economic crisis in Cuba worsened, attempts to cross the Florida Straits increased. Initially, the Cuban government prosecuted those attempting to leave, but, just as the rafters had become heroes in Miami, popular sentiment in Cuba was with them as well. After all, many of the rafters were individuals without the means to make their way to the United States through official channels or the money to pay the exorbitant black market rates.8 Throughout the island friends and relatives of potential rafters collected water jugs, spare tires, sheets, and food to aid in their efforts. Yet looming over the festivity of going-away parties was a sense of danger and fear for the rafters who were heading out to sea. In Miami empty rafts or bodies washing up on shore provoked collective outpourings of grief.9

Despite the rise in the number of rafters, the preferred mode of entrance for Cubans into the United States during this period was overstaying a tourist visa. As part of the reinstated immigration treaty, the United States granted fifty thousand tourist visas per year to Cubans. Initially, the Cuban government placed an age restriction on the distribution of exit permits for these visas. When the age limit of 65 was lowered, the number of tourists who remained in the United States rose from 5 to 15 percent. This meant that approximately seventy-five hundred Cubans per year were migrating to the United States by overstaying their visas. But, for Cubans without relatives in the United States who would pay for their trips, las Balsas (the rafts) were the only recourse.

Cuba after the Fall of the Socialist Bloc

The 1987 reinstatement of the immigration treaty was met with enthusiasm by Cuban officials even though they had canceled the treaty two years earlier. In reality it had been Fidel Castro who had ordered the termination of the treaty as a way of punishing the exile community for its supposed support of Radio Martí. Castro’s advisors -functionaries and academics who were assigned to study the Cuban community abroad—had favored revising the harsh policy toward émigrés. In addition, they called for a more comprehensive understanding of why people left the island, thus challenging the characterization that émigrés were political traitors.

In 1986 the Ministry of the Interior was asked to establish a commission to investigate the “problem” of the Cuban-American community and develop a set of recommendations. The commission was staffed by academics at the University of Havana who were involved in studying the issue. Mercedes Arce, a social psychologist specializing in the psychology of the community, became its key staff member. Many of these academics provided policymakers with a more comprehensive vision of the emigration process itself as well as with the nature of the Cuban-American community in the United States.10 Emigration, they argued, was a complex phenomenon, one not to be viewed solely as a matter of political treason. They set out to study the factors contributing to the decision to leave. Some concentrated on understanding the socioeconomic makeup of the émigré community. Others studied the politics. The Centro de Estudios Sobre America (CEA) responded to the Department of the Americas of the Central Committee of the Party. Its focus was on understanding Cuban immigration within the context of U.S.-Cuban relations.

Despite the bureaucratic turf wars among these various centers, most academics agreed on a series of recommendations aimed at developing a more realistic policy toward the communities abroad. The commission—which also included representatives of the various ministries and offices concerned with emigration—recommended that policies should treat leaving as a normal phenomenon, not a political one. It urged, moreover, that policies should strive to depoliticize the act of leaving and the exile community’s concern about homeland, rather than punishing people for leaving the country.

Eventually, changes were implemented in Communist Party directives that, until then, had instructed workplaces to fire anyone who applied for an exit permit. School policies that had previously discriminated against children whose parents applied for exit permits were also changed. Prior to the policy revision, for example, children were often taken out of gifted programs as a form of punishment for what the government described as their parents’ betrayal of the revolution. Because it often took years to secure a visa to leave the country, harsh policies such as these had created a disaffected class. By the time they finally did leave, many were adamantly opposed to the regime—indeed, much more so than they had been at the beginning of their waiting periods.

In 1989 the center at the University of Havana that studied U.S. Cuban relations spawned another office called the Centra de Estudios de Alternativas Politicos (CEAP, Center for the Study of Alternative Policies), and Arce became its head. This new center worked closely with functionaries at the Ministry of the Interior who, while having a national security perspective on the politics of the exile community, were eager to become more pragmatic in their dealings with those abroad.11 It promoted academic and social exchanges, often reaching out to groups in Miami that had been shut out of their home country. But this work was as controversial in Cuba as was support for better relations with the island in Miami. Those who studied the Cuban exile community were even referred to as “gusanologos.”

Furthermore, as open-minded as some of the functionaries at the Ministry of the Interior were, the purpose of the bureaucracy they worked for was to repress dissent, whether in Cuba or in the communities abroad. One of their goals was to depoliticize the exile community through various means, including the toning down of the negative rhetoric surrounding the emigration process itself. Another goal was to isolate the extreme right-wing portion of the community abroad through a “divide and conquer” strategy.12

In autumn 1989 St. Mary’s University in Nova Scotia, Canada, sponsored a conference on the future of Cuba. Since the official dialogue between the Cuban government and the community in 1978, there had been little contact between exiles and Cuban government officials. A high-level Cuban delegation attended this meeting, as did leaders of many exile opposition groups, including Carlos Alberto Montaner, an exiled writer living in Spain, and Enrique Baloyra, at the time professor of political science at the University of Miami. The informal hallway discussions became more important than the formal sessions, as Cubans from on and off the island talked and debated. Upon returning to the island, Ricardo Alarcón, at the time the Cuban minister of Foreign Relations, held a press conference in which he referred to his positive meetings with Cuban exiles. This was a dramatic statement, since there had been no positive references to exiles in the state-controlled media for more than a decade.

A flurry of memos was generated by those Cuban government officials who had attended the conference. Ricardo Alarcón wrote to Jorge Risquet, who was at the time in charge of foreign relations for the Politburo of the Communist Party, recommending a revision of Cuba’s policies toward the community. Alarcon understood that the immigration process was complex and should not be seen simply as an act of treason to the revolution, and he wanted Cuba’s emigration laws to reflect this. He also stated that all U.S. administrations had used the Cuban community in their policies toward Cuba and, as such, it would be in Cuba’s interest to study ways of normalizing aspects of its relationship to that community through more regularized travel and communications. Other analysts recommended identifying sectors of the community interested in better relations, such as businesspeople and those who had relatives on the island. Rafael Hernandez, of the Center for the Study of the Americas, and José Antonio Blanco, at the time with the Central Committee’s Department of the Americas, both supported changing policy but warned about the impact on the population. Blanco insisted that domestic politics should be the starting point for any discussion.13 Economic arguments for a policy change were considered as well. The CEAP prepared financial charts that included projections of how much hard currency Cuba could earn if the number of reentry permits was increased and if those who left through Mariel were allowed to return.

Underlying these discussions was a growing realization that the economic collapse of the Soviet Union would have serious consequences for Cuba’s economy. Fidel Castro was announcing what was called the ‘"Zero Option,” measures that everyone must submit to in order for the country to ride out the economic collapse.14 (One measure was the use of collective kitchens to conserve fuel.) Popular pressure was mounting on the government to resolve the economic crisis. In this context the continued war with the exile community seemed counterproductive, since many knew that their relatives could help them weather the difficult economic situation.

In 1990 Cuba’s Communist Party announced that restrictions on island residents for travel abroad would be minimized. The Cuban government progressively lowered the age of those allowed to leave the country from sixty-five to twenty, dramatically increasing the number of people allowed to travel abroad.15 As a result of the reinstatement of the immigration treaty with the United States, Cuban citizens were now eligible to apply for tourist visas. In turn Cuba doubled the number of Cuban-Americans allowed to visit the country. As a result, contact among Cubans on and off the island increased significantly.16

Increased Contacts

One important and unexpected development of lifting restrictions was that Miami, long inhabited by Cubans who had left the island permanently, suddenly became a center for island visitors. At first Cuban visitors were treated as a rarity. They were bombarded with political questions: were they members of the Communist Party? did they support Fidel? But, little by little, politics gave way to family concerns and friendship, and, as the walls came down, fear subsided, and the real stories of Cuba began to be told. People from the island also developed a more realistic view of life in the United States as they watched relatives struggle with jobs and daily existence. Visitors from the island became a staple in Miami; many Cuban exiles had relatives visiting or knew someone who did. With heightened contact travel to and from the island lost its political connotations.

Needless to say, these visits created a cottage industry of businesses designed to facilitate contact. Given the deterioration of underwater cables between the United States and Cuba, telephone calls were limited and several companies were established to provide alternative routes for phone calls. Companies providing mail service also materialized.17 Passports, travel documents, visas, extensions on visas, and the trips themselves all carried fees, paid for by Cuban exiles.18 Cubans often returned to the island with so many gifts that families in Miami were depleted of resources after their visits. Unlike the exile visits to Cuba in the late 1970s that had spawned resentment on the part of islanders without relatives abroad, the visits to Miami had less of an impact. They took place in another country rather than on the island, yet the Cuban government still reaped financial gains.

Increased contact with the Cuban community in Miami had an effect on the opposition groups on the island, which began calling for national reconciliation with those abroad. These groups were met with repression by a government that feared an internal revolt and that wanted to make sure that a leader capable of organizing such a revolt did not emerge. Particularly threatening to the government were groups that had developed coherent political programs with platforms that could be characterized as to the left of the regime and that incorporated many of the unmet demands percolating through Cuban society. Groups who could claim historical legitimacy were seen as especially dangerous to the regime.19

The most significant figures to emerge from the internal opposition movement were Sanchez, Gustavo Arcos, and Ricardo Boifill. Boifill left the country in the late 1980s and began working with CANF. Arcos had been a member of the July 26 Movement, Fidel Castro’s original group, and had participated in the attack on the Moncada palace (the military action that had signaled the beginning of the armed movement against Batista), but he had broken with Castro early on and spent most of the revolution in jail. Arcos’ group called for a return to the revolutionary principles of the July 26 Movement. Sanchez, a former mathematics professor at the University of Havana and member of a group that had advocated Marxism in the 1960s, criticized the revolution from the left. He championed a radical social democratic platform that included a call for national reconciliation and a dialogue between the opposition on the island and abroad and the present Cuban government. Interestingly, most opposition platforms called for a national dialogue and reconciliation among all Cubans, including those abroad. In a reversal of the 1970s, when the government had taken the lead in calling for a dialogue, now it was the opposition that did so.

By 1990 more than fifteen human rights opposition groups were operating on the island. Although their numbers were small, their political discourse gained ground among intellectuals. More important, their nationalist appeal found support among the vast numbers of the population who were increasingly excluded from the “New Cuba” created for tourists, foreign capitalists, and well-positioned government bureaucrats. Perhaps sensing the growing support for these organizations, the government stepped up the arrests of various leaders, and jail sentences were increased. Many of those detained were given the option of either going to prison or into exile. Concurrently, there was a renewed attack on those leaving as the “new gusanos.” As such, the émigré community once again became an issue by which to measure loyalty to the revolution.

But in the 1990s these attacks had unexpected consequences. For instance, in December 1990 artists and professors at the Ministry of Culture’s Art Institute fended off a rather amateurish attempt by Young Communist Party functionaries to take control of the institute. The takeover attempt was led by up-and-coming politician Carlos Aldana, who had previously attempted to seize control of the national film institute. The art students staged a mass meeting and circulated a petition defending their right to create freely. Most surprisingly, they demanded that the definition of Cuban culture include what was created both on the island and abroad.20

Intellectuals in Cuba, as in most developing countries, generally have been at the vanguard of the defense of the nation and its cultural life. Adding to this complex phenomenon at the time was an economic crisis that forced many creators off the island. A large number of creative projects, such as literary magazines, were compelled to find homes and financing outside the country.21 In addition, hard-liners wanted intellectuals who were increasingly critical of the regime out of the country—a position that coincided with that of reformers who supported freer travel for intellectuals. As a result, many writers and artists began spending long periods of time abroad.

This development solved two problems: for the hard-liners keeping intellectuals off the island meant rendering them invisible and thus less threatening; if they stayed away long enough, it would even become possible to question their legitimacy. For intellectuals travel meant cultural and discursive exchange and real income that could be spent on real goods—opportunities not readily available at home. By 1992 the official count of Cuban artists and intellectuals living in Mexico alone stood at more than four thousand. Needless to say, these people, who did not identify themselves as exiles, were extremely interested in redefining state policies that framed those abroad as traitors and that prohibited the publication of articles or books in Cuba that were originally published outside the country. In 1991 this crisis led the Cuban Communist Party Politburo to promote Abel Prieto, a writer, to the presidency of the state-run Union of Writers and Artists. It marked the first time that someone from the cultural sphere occupied such a post.

Yet these changes were mainly symbolic. When amendments to the constitution redefining regulations on work and travel abroad were proposed, those favoring the exclusion of Cubans who had left the country won out, when the votes were tallied in the National Assembly. As a result, in the summer of 1992 the Cuban Constitution was amended to reiterate that all those who had taken on the citizenship of another country would lose their Cuban citizenship.

Bureaucratic turf battles prevented any restructuring of policy toward the community. The communities abroad project, heretofore run from within the Ministries of Foreign Relations and the Interior, was now placed under the supervision of Carlos Aldana’s department in the Communist Party. Aldana approved several projects aimed at reforming policies affecting the communities abroad, but his reform credentials had long been questioned by intellectuals and artists, who saw him as an opportunist willing to speak several political languages, especially when an international public image was at stake. To them Aldana seemed quick to compromise his principles; while he might argue for radical reform one day, the next he could be seen on national television demanding the heads of human rights leaders. This impression was reinforced by Aldana’s strategy within the Communist Party of creating an alliance with reformers and pragmatists while covering his political flanks by repressing intellectuals, artists, and human rights advocates.

In August 1992 Aldana made a weak attempt at a bureaucratic coup popularly called “La Reina Elizabeth.” The idea was to take control of the bureaucracy, leaving Castro as a figurehead. Aldana’s alliance included sectors of the Ministry of the Interior, particularly those working on the Cuban community project—a group that included relatively open-minded functionaries as well those who had access to a steady source of hard currency. But, when Castro returned from the 1992 Summer Olympics, Aldana and everyone around him was fired and sent to agricultural work farms. Those stripped of power included people who were coordinating various components of the Cuban community project, such as Arce; Jesus Arboleya, director of the community project for the Ministry of the Interior since 1975; and Manuel Davis, who had been the first secretary at the Cuban Interests Section in Washington and was now working in the Ministry of Foreign Relations’ U.S. Department overseeing programs related to the émigré community.22 None of these events was reported in the Cuban press, but they were widely known and discussed nonetheless.

As 1992 came to an end, the possibilities for reform through established channels diminished. Cuba was in a holding pattern. Political repression and the lack of grassroots activism severely constrained the potential for change. Younger party functionaries understood that those holding the reins of power would not give them up easily and conveniently switched their allegiance from the reformers to those in power. This would give Cubans the illusion that Castro was transferring power to a younger generation. Yet. unlike the generation that had fought in the revolution, the thirty-somethings had no claim to historical prestige and thus did not pose a real threat to Castro. As a result, these young functionaries were extremely cautious about the reform projects they proposed, avoiding those that might give the appearance of disloyalty. Supporting a change in policy toward those who had left the island clearly fit this category. Yet the crumbling of the ideological framework that had held the island together for thirty years set off a fierce political debate -albeit within the constraint of a repressive government—about what should replace it.

The Cuban Exile Community: An Old Debate Resurfaces

Events on the island had a ripple effect in Miami. In the spring of 1990 a powerful bomb exploded outside Miami’s Museo de Arte Cubana Contemporanea. one of the few organizations willing to exhibit paintings produced by island-based artists, causing considerable damage to the building and its artwork.23 The museum’s director at the time, Ramón Cernuda, had argued for a change in U.S.-Cuban relations. The year before he had become the victim of a concerted federal government campaign of harassment that began with Treasury Department agents storming his house in the middle of the night and taking possession of his art collection, which included works painted by artists living on the island.24 (The federal courts eventually ruled in Cernuda’s favor and proclaimed that art was a form of information that could not be censured by the federal government.)25 Cernuda was also the U.S. spokesman for the Cuban Commission on Human Rights and National Reconciliation, an island-based human rights group.

What was ironic about the targeting of Cernuda by right-wing exiles was that, like other anti-Castro activists, he advocated an end to totalitarianism in Cuba and to the one-man rule of Fidel Castro.26 But, unlike others, Cernuda believed that the best way to bring about political change in Cuba was not through confrontation but by ending U.S. economic and diplomatic hostility toward Cuba.27 This put Cernuda at odds with Jorge Más Canosa, president of CANF, as well as with the Bush administration, and it allied him with those Cuban exiles who supported better relations between Cuba and the United States.

The Cernuda bombing showed that, while Cuban exiles could be concerned about domestic issues and be willing to play politics “a la americana,” Cuba continued to be a predominant concern of the community. Furthermore, even though organizations had emerged that lobbied on foreign policy issues, the political culture of the community, particularly in regard to resolving issues pertaining to Cuba, was heavily influenced by terrorist activities that had originally been promoted by the U.S. government.

Perhaps the greatest significance of the Cernuda event was that it reflected a subtle yet important realignment taking place within the Cuban exile community: Some exile organizations, taking their cues from opposition groups on the island, were embracing a more nationalist political agenda than that favored by earlier organizations, most of which were closely tied to U.S. interests. These groups also advanced a more moderate agenda that called for dialogue with the Cuban government, thus allying themselves with organizations that had emerged in the 1970s calling for the same.

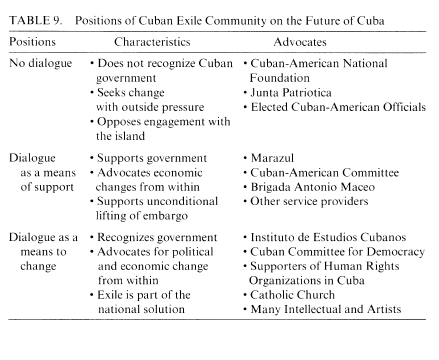

From the late 1980s to the early 1990s the Cuban exile community was consumed with debate over the future of Cuba. Two currents of thought—one pro-dialogue, the other anti-dialogue—dominated the community’s views on how to relate to Cuba. These positions were by no means monolithic.28 Each had real consequences for U.S.-Cuban relations and for the development of the community (see table 9).

The Anti-Dialogue Position

The anti-dialogue forces had two principal constituencies: those who advocated the overthrow of the Cuban government through military action and those who favored its destruction through economic and political isolation. Organizations favoring military action emerged mostly in the early 1960s and were closely linked with U.S. military projects. Groups such as Alpha 66 and the Brigada 2506 were in this tradition. Other, similar groups were driven underground in the late 1960s, when U.S. policy toward Cuba shifted from military confrontation to political isolation. They continued to operate underground and employ terrorist methods.29 In the 1980s what they perceived to be the imminent fall of the Castro government rekindled their militarism.30

Orlando Bosch, a leading advocate of this strategy, received renewed attention in 1990, when the Bush administration granted him entrance to the United States from Venezuela despite prior parole violations. He had been jailed for firing a bazooka at the FBI offices in Miami. Bosch, a pediatrician by training, had been a close supporter of Fidel Castro but joined the opposition in the early 1960s. In the mid-1970s he coordinated a coalition of groups engaged in terrorism that targeted not only the Cuban government but any government or entity that maintained relations with the island government. In 1973 he was implicated in the bombing of a Cuban airliner carrying seventy-three Venezuelan athletes to the island that exploded shortly after takeoff. The significance of these terrorist groups declined in the 1980s, but they still contributed to an authoritarian political culture in the Cuban exile community by silencing their detractors with violence and intimidation. Indeed, during the period Miami had the dubious distinction of being the U.S. city with the highest number of bombing incidents and political assassinations.

In November 1991 a local television channel in Miami recorded a meeting between the military chief of Alpha 66. a post-Bay of Pigs organization involved in terrorist acts, and a Cuban United Nations official. The meeting, which took place in New York, suggested that Alpha 66 was infiltrated by Cuban security agents. This raised publicly a question often asked in private: who exactly was behind the bombings in Miami? was it beneficial to the Cuban government for Miami to be seen as a hotbed of anti-Castro terrorists? Clearly, the presence of Cuban double agents in the most extremist organizations suggested that at least part of the right-wing violence was encouraged by the Cuban government.

The other principal anti-dialogue advocates believed in fighting the Cuban government with economic and political pressure. Members of political organizations such as CANF had their roots in the 1960s, but they came of age during the Reagan administration, and they continued to enjoy White House access during the Bush years. The close connection between the political agenda of these groups and that of the United States gave them little legitimacy in Cuba; they were perceived as mere appendages of U.S. interests, not as independent political forces. They were also less likely to have links with internal opposition groups on the island. This became particularly obvious in the years following the fall of the socialist bloc, as these organizations devised economic, political, and social plans for the future of Cuba without the participation of Cubans living on the island.

Like the old guard, these groups had a highly authoritarian political culture, as evidenced in particular by the autocratic tendencies of CANF president, Jorge Más Canosa. Más Canosa treated his opponents harshly and tolerated no dissent from his staff. Moreover, the agenda of choking the Cuban government at all costs raised questions about the real motives of CANF and similar groups. Many felt that CANF did not represent them. Only 36 percent of Cuban-Americans polled in 1988 believed that “rightist groups such as CANF represented their views.”31 Many exiles feared that CANF’s policies might spark an internal situation on the island in which violent clashes could erupt. This was not a desirable outcome, especially for Cubans with relatives on the island. Furthermore, most Cuban exiles, regardless of their feelings toward Castro, wanted to establish and maintain contact with their families. But CANF claimed that any negotiations with Castro would only buy him more time and supported a strategy of total isolation as a way to depose him more quickly.

Despite the controversy surrounding its policies, CANF made its presence felt, especially in the U.S. Congress. Working closely with a political action committee, CANF made sizable donations to key members of Congress. In the late 1980s these lobbying efforts extended to other governments as well. CANF even set up an office in Moscow to lobby Russian officials to cut ties to Cuba and hired Russian authors to write editorials urging their government to sever ties with the island.

CANF managed to alleviate the misgivings of Cuban exiles and deepen its roots in the exile community through a government contract they were awarded by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. The contract authorized them to identify Cubans in third countries, such as Mexico and Russia, who should be granted visas by the INS.

In Florida CANF tried to influence the development of ideas by creating a fund that would match state spending on Cuban studies at Florida International University (FIU), a state school.32 After a long battle FIU refused the offer, and the program went to the University of Miami, a private institution.33 CANF also tried to set the cultural agenda for the Cuban émigré community by actively promoting the denial of visas to any performing artists from the island. In the spring of 1989, for example, the City of Chicago invited Orquesta Aragon to participate in a Latino music festival, but at CANF’s behest the State Department denied the group’s visa application.34

CANF did lose some prestige when it declared war on the Miami Herald, claiming that the newspaper was too critical of the foundation. Más Canosa called for a boycott of the Herald and went so far as to place advertisements to this effect on local Miami buses. These actions showed that, while he claimed to want to bring democracy to Cuba, Más Canosa was unwilling to support institutions that were part of a democratic system, such as newspapers, when they were critical of him.35 Bumper stickers appeared in Miami that read, “Más Canosa y Fidel Castro: la misma cosa” (the same thing). And. despite CANF’s extensive campaign, newspaper circulation did not suffer measurably.

Whether CANF would have the same degree of influence without the aid of U.S. politicians is subject to debate, but it is clear that CANF has demonstrated enormous political clout in lobbying for its projects even when it has failed to receive the blessing of the White House. Such was the case with the development and passage of the Cuban Democracy Act, a bill that called for tightening the economic embargo of the island by prohibiting U.S. companies based outside the United States from conducting business with Cuba. Initially, the Bush administration vetoed proposed bills along this line because they posed problems for the international community by calling for U.S. subsidiaries in third countries to cease doing business with Cuba. Canada was among those that protested, arguing that, if passed, these laws would violate its national sovereignty. Canada then issued a warning that, if Canadian-based U.S. companies were prohibited from conducting business in accordance with Canadian laws, they would be expelled from Canada. Restrictions on U.S. companies in third countries also ran contrary to the president’s attempts to negotiate free-trade agreements with North American and Latin American countries.

In response CANF formed a bipartisan congressional support group that included representatives from Florida and New Jersey. The White House reacted by restricting the unbridled access to administration officials enjoyed by CANF and put out a timid call to other groups in the Cuban exile community to come forward.36 Bush was hoping to bring on board moderate groups that supported his policies but were against CANF. But, with no follow-through from the White House, the invitation fell by the wayside. Part of the problem was that the Bush administration did not understand the political landscape of the moderate and progressive sectors of the Cuban exile community.

These setbacks did not dampen CANF’s efforts, and the organization proceeded with its plans. While White House support for CANF’s legislative agenda had weakened, there were plenty of congressional representatives willing to do its bidding. Momentum for comprehensive legislation to tighten the embargo grew in Congress as representatives who received large donations from “Free Cuba,” a political action committee closely tied to the foundation, either dropped their opposition to tightening the embargo (this group included senators Claiborne Pell of Rhode Island and Paul Simon of Illinois) or enthusiastically supported it, as was the case for Congressman Robert Torricelli. a Democrat from New Jersey.

Torricelli was a junior legislator on the lookout for issues that could help him make his mark in Congress. Getting tough with Cuba gave him a national forum on foreign policy, and it helped his standing with New Jersey’s conservative Cuban community. Torricelli was instrumental in helping to draft and introduce the Cuban Democracy Act. In addition to provisions calling for the tightening of the embargo, one of the bill’s stipulations was the opening of new communication channels to Cuba, a provision put forth by AT&T, whose headquarters were located in Torricelli’s district. The bill also outlined steps to be taken by the United States after the fall of Castro, including specifics about when to begin the delivery of aid packages.

Despite support for the legislation from conservative exile organizations, other groups argued that choking the island with the Cuban Democracy Act would produce neither democracy nor stability and urged that alternative solutions be explored. Ramón Cernuda (who would later become the target of terrorist opposition) testified, for instance, that the embargo only strengthened hard-liners in Cuba, giving Castro ammunition with which to clamp down on groups and individuals on the island pursuing change. Instead, these groups encouraged lifting the embargo.

Other organizations, including the Cuban-American Committee, testified that the tightening of the embargo hurt Cubans in the United States who wanted to enjoy a normal relationship with their homeland. They argued that lifting the embargo would help liberalize Cuba’s policies, particularly those aimed at its communities abroad. Without the economic blockade the Cuban government would not feel as threatened and could be more open in its dealings with the Cuban exile community. Indeed, this had already occurred during the brief moment of detente in the late 1970s, when changes in Cuba’s policies toward the exile community were accompanied by political and economic openings on the island.

Yet in the heat of the 1992 presidential campaign the Cuban Democracy Act was passed by Congress. Bush, facing a close election, signed the bill in the hope of improving his chances in Florida, a critical state. Bill Clinton, the Democratic candidate for president, endorsed the legislation prior to its signing. Both actions were surprising: Bush had previously opposed the bill, and Clinton had stressed the need to develop a post-cold war vision of the world. But the bill passed, thanks in part to donations from CANF’s political action committee. CANF had made the legislation its top priority and contributed $500,000 to key congressional representatives and candidates.

In many ways this was simply money recycled from the GOP. CANF’s power was a product of a give-and-take relationship with the Republican administration. CANF would donate funds to Republican officials and candidates and in turn receive lucrative government contracts. From 1984 to 1990. for instance. CANF received $780,000 from the National Endowment for Democracy, an agency whose mandate is to promote pluralism abroad. Despite protests from Miami-based groups about CANF’s antidemocratic practices and comprehensive reports in the Miami Herald questioning the use of government funds for relocation of Cuban immigrants from third countries, the Bush administration closed its eyes and continued promoting and working with CANF, locally and nationally.37

Yet, if support for the bill was a payback, the benefits eluded many. The Cuban Democracy Act did not provide any new solutions but, instead, rehashed a long-standing U.S. government practice of demanding change in other countries through economic or military force. Curiously, this time around the harsh anti-Cuban rhetoric was intended to appeal to Cuban-American voters. Rather than debating issues or bringing a plurality of voices into their campaigns, both candidates appealed to voters through ethnic stereotypes. Ethnicity was not only a factor in bringing people together in the electoral arena: it was also a campaign method for mobilizing voters and money. Yet the approach to ethnicity taken by campaign organizers was based on simplistic stereotypes. Candidates wore “Mexican hats” and exploited photo opportunities with the president of Mexico when visiting San Antonio or ate black beans and rice and inveighed against Cuba when they were in Miami. Instead of ethnic lobbying, the passage of the Cuban Democracy Act was an attempt to lobby “ethnics.” Outside of an election season bills similar to the Cuban Democracy Act had simply failed to pass Congress or receive the president’s endorsement.

For Clinton the strategy failed. He received less than 20 percent of the Cuban-American vote, only a bit more than Michael Dukakis, who had not beat the anti-Castro drums, in his bid for the presidency four years earlier. This was almost certainly less than what Clinton would have received had he developed a strategy of engaging newcomers and protecting the exiles’ relationship to homeland. According to a Gallup poll, a majority of Cuban-Americans who identify themselves as Democrats were in favor of negotiations and diplomatic relations with Cuba, were likely to visit Cuba if it were made simpler to do so, were inclined to think that the Cuban people rather than the leadership have been hurt by the embargo, were likely to have become U.S. citizens, and were likely to vote for a candidate who favored improved relations.38 With a different strategy Clinton could have become the champion of these individuals’ rights to travel, invest, and engage in activities denied to them by the Cuban government.

The international reaction to the passage of the Cuban Democracy Act was as the White House had feared. The controversial U.S. law was condemned at the United Nations. The Canadian government decreed that any company violating its laws, which permit commerce with Cuba, would be asked to leave Canada. Mexico and the European Community filed formal protests. And, strangely enough, both Bush and a newly elected Clinton came under attack by those to whom the bill claimed it was bringing democracy: anti-Castro human rights groups in Cuba. These groups believed that the bill violated Cuba’s sovereignty by attempting to legislate democracy through a foreign government. Nonetheless, as Clinton assumed the presidency in January 1993, he did so bound by a relic of cold war policy. (Ironically, Roger Fontaine, who had been instrumental in helping organize CANF, now criticized the president for letting Cuban exiles run U.S. foreign policy.)

Meanwhile, a multitude of groups began planning for the situation after the fall of Castro. The Cuban-American Bar Association commissioned the writing of a new constitution. CANF initiated a fund-raising campaign aimed at Fortune 500 companies. In return for their financial contributions companies were offered an inside track for negotiating with post-Castro political actors on the island.39 The governor of Florida commissioned a series of working papers on the impact that the fall would have on south Florida, including what contingencies would be needed for police deployment on the night of the festivities.

Pro-Dialogue Forces

In part because of the void created by hard-line politics in the Cuban exile community, in the early 1970s groups emerged that began calling for a normalization of relations with the Cuban government. The first of these were organized by younger Cuban exiles who were raised outside the homeland, but later other groups formed that included people whose families had been divided by politics.

When the Reagan administration came to power in 1980, the Dialogue was already coming apart, and Reagan’s policy of confrontation with Cuba accelerated its demise. Yet with the 120,000 émigrés who came to the United States via Mariel also came a new generation of immigrants who further diversified the community. Although these émigrés resented the Cuban government for its mitines de repudio (meetings to repudiate those who were leaving), they had a very different relationship with the relatives they had left behind. So. just as the exchange programs of the late 1970s were being dismantled, a new group in the exile community was asking the United States to maintain open doors to its homeland.

The organizations that emerged in the late 1970s were varied. Some, such as the Antonio Maceo Brigade, made support of the revolution part of their political strategy. Others, such as the Cuban-American Committee, advocated changes in U.S. policies and focused on Washington. Those with the deepest roots in the exile community were service providers, such as the travel agencies that arranged trips to Cuba. From these service providers several organizations arose in the late 1980s that mobilized Cuban émigrés with relatives in Cuba to pressure U.S. policymakers. One such organization was the Cuban-American Pro-Family Reunification Committee, headed by Carmen Diaz, a former professor at the University of Havana who left the island via Mariel in 1980.40 During the 1988 U.S. presidential campaign the group organized a breakfast meeting at which more than three thousand people supported an agenda calling for negotiations with the Cuban government. Another group, the Cuban-American Coalition, incorporated a political action committee headed by a former Jesuit priest, José Cruz. In the first weeks of its formation more than eight hundred people signed on and donated money to the PAC.41 A political activist in a similar vein was Francisco Aruca, the president of Marazul Charters, who launched a radio program in Miami to provide an alternative viewpoint to the Cuban exile right-wing establishment.42

Politically, these groups focused their activities on the U.S. government. While privately they advocated changes in Cuban policy, in public they were more critical of U.S. policy. Seen as sympathetic to the Cuban government, they had the trust of its officials but failed to capture a wide spectrum of political support in the Cuban community. In addition, groups such as the Cuban-American Coalition became embroiled in corrupt practices such as accepting “donations” from individuals who wanted to travel to Cuba. The number of passengers allowed entrance by the Cuban government each month varied, but it was always small, and the coalition would guarantee that its donors were sold a ticket to travel to the island. Furthermore, the radio style of the head of Marazul, Aruca, was no different than that of right-wing radio personalities. People who called the radio show’s open line and disagreed with him would be yelled at and ridiculed. Many wondered what alternative he was providing.

The political landscape of the community did change, however, with the emergence of organizations linked to the island-based human rights groups that began to appear in the mid-1980s. These human rights organizations included a Catholic group, Movimiento Cristiano Liberation headed by Oswaldo Paya and La Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos (the Human Rights Coordinator) led by Elizardo Sanchez. Such groups called for a political opening not only on the island but in Miami as well. The emergence of Cuba-based human rights groups and the growth of exile organizations that sought out links to the island were intimately related: without an internal opening in Cuba that allowed human rights groups to exist, the parallel phenomenon in Miami would not have occurred.

The close relationship between groups abroad and internal opposition in Cuba had a tremendous impact on the development of a more contemporary political discourse in the Cuban émigré community, one that sought solutions to problems on both sides of the Florida Straits. These groups took the lead when, with the collapse of the socialist camp, discussion resurfaced within the Cuban exile community about its relationship to Cuba and the future of the island.43

In 1989 an affiliate of the International Christian Democrats (directed by Enrique Baloyra in Miami), the Social Democrats on the island, La Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos (headed by Ramón Cernuda in Miami and Elizardo Sanchez in Cuba), and the Liberal Union (coordinated by Carlos Alberto Montaner in Madrid) coalesced to form the Democratic Platform. The groups abroad, like traditional organizations in the exile community, were militantly anti-Castro; in fact some of the leaders, such as Baloyra, had fought in the underground against the revolution. Yet, unlike the Right, they advocated a political strategy that emphasized change on the island and opposed U.S. hostilities. This placed these groups in the great dialogue divide on the same side as the family reunification forces sympathetic to the revolution.

Yet there was a crucial distinction between the objective of these organizations and that of the pro-family groups. The pro-family organizations argued for an end to U.S. hostility in order to help democratize the island so that opposition groups could flourish and participate. They felt that, if Castro could not use the threat from the United States to manipulate Cuban politics, he would be forced to make political changes. In contrast, the goal of the Democratic Platform was to hasten the democratization of the island in order to end Castro’s one-man rule.

The Democratic Platform was viewed with suspicion by Cuban government functionaries. The Cuban government saw the new human rights groups as tools of the United States rather than organizations truly interested in the welfare of the Cuban nation. Contributing to this perception was the manipulation of human rights issues by the United States, particularly in the United Nations, under the direction of Armando Valladares, former U.S. ambassador to the Human Rights Commission, who was now working with CANF.

Yet the coherence of their political discourse and their emphasis on democracy and social justice in Cuba and Miami earned the groups that make up the Democratic Platform political legitimacy on both sides of the Florida Straits. Some, like Cernuda’s Coordinadora de Derechos Humanos, found a new following among newcomers from the island who, perhaps more than their longtime exile counterparts, understand that a post-Castro solution must include many forces but fundamentally must come from inside the island. While not all platform groups agreed with this strategy (notably Montaner’s Liberal Union), most organizations in this tradition support the position that change in Cuba should be internally driven.

There were many other individuals and sectors in the Cuban exile community that were not necessarily aligned with pro-dialogue forces but that supported reconstruction of a respectful relationship with the homeland. Many of these people had either been raised in the United States or had arrived recently. Some were part of the organized Left that at first had been unequivocally supportive of the Cuban revolution but later had developed a more critical perspective. Some became disillusioned with the lack of democracy within right-wing organizations and changed their philosophies accordingly. Thus, a new synthesis occurred within the Cuban exile community between a core of individuals seeking respectful engagement with Cuba and the creation of a new political culture among Cubans on and off the island. This was particularly evident among intellectuals and artists as well as younger business professionals.

In Washington the Cuban-American Committee attempted to tap the energies of these individuals. It initiated a discussion called the Second Generation Project with the goal of finding policy solutions to reconstruct a relationship between Cubans abroad and those on the island. Initially, the committee proposed a meeting to coincide with the thirtieth anniversary of the Bay of Pigs invasion to demonstrate that a new generation was coming of age that was unwilling to continue the war. But the Cuban government rejected this offer. Even the words second generation were offensive to government functionaries because they implied a defiance of the “first generation” of Cuban leaders, principally Fidel Castro. The Second Generation Project was ultimately approved, although many of the invitees from the island were not allowed to participate. In some cases it was Cuba that forbade their involvement, while in others it was the U.S. government’s refusal to grant a visa that prevented participation.

Nonetheless, in autumn 1991 thirty Cubans from Cuba and the United States, myself included, met on St. Simon’s island off the coast of Georgia at an event sponsored by the Cuban-American Committee. Despite the restrictions by both governments, the group was eclectic and included physicians, professors, artists, economists, businesspeople, teachers, and journalists ranging in age from their mid-twenties to early forties. For some it was their first trip to the United States; for others it was their first meeting with Cubans who had remained on the island.

From the meeting emerged a general consensus that a relaxation of tensions between Washington and Havana would aid democratization on the island and that the time for this process was ripe given that the major points of contention between Cuba and the United States had been resolved by the end of the cold war. The group identified U.S. and Cuban policies and practices that impeded a normal relationship between those in the Cuban exile community and those on the island. We agreed to ask our respective governments to initiate discussion on the bilateral issues that deeply affected the one million Cuban exiles living in the United States as well as the ten million Cubans on the island—issues such as travel, immigration, and business, professional, and cultural exchanges.

Yet there were major disagreements during the discussion of human rights, since some island-based participants felt that anyone abroad who supported Cuba’s human rights groups was an enemy of the revolution. Others, myself included, argued that, within the Cuban exile community, many who supported human rights groups also advocated dialogue with the Cuban government. Furthermore, we asserted that a close tie existed between Cuban government attitudes toward internal opposition and its policies toward those who had left, so that in order to resolve one issue the other had to be resolved as well. Ultimately, the Cuban-American Committee opted to nurture its relationship with younger government and party functionaries rather than try to build an effective coalition in the exile community. Therefore, its effectiveness in the community—and for that matter on the island—was limited.

Another important organization involved in efforts to build a process of reconciliation was the Instituto de Estudios Cubanos (Institute of Cuban Studies), headed by María Cristina Herrera, who for more than twenty-five years had advocated open lines of communication across the Straits of Florida. Hers was one of the few groups that succeeded in creating a forum in which the Left and the Center came together in a series of working conferences at which participants engaged in the kind of debate that could not otherwise occur either in Cuba or in Miami.

In the early 1990s members of the institute launched a research and education fund. The new organization, the Cuban Committee for Democracy, succeeded in bringing together long-standing members of the Democratic Party such as Alfredo Duran and newly arrived intellectuals such as Madelin Camara in an effort to create an alternative to CANF.44 Unfortunately, however, the group established a membership structure that required a thousand-dollar membership fee in order to have a vote—a structure not unlike that of the very organization it set out to counter.

Diverse Political Visions

Underlying the two dominant political positions in the Cuban community were various assumptions. Those who favored complete isolation assumed that the internal opposition was either too weak or too compromised by political limitations and repression to be effective, thus the impetus for change had to come from outside the island. In contrast, those who supported dialogue as a means to change the regime had contact with internal opposition groups and knew that there was an effective opposition operating on the island. These latter exile groups connected the Cuban government’s policies toward dissidents to U.S. policies. They argued that, whenever U.S. policies eased, so did Cuban government policies toward them. Without the external threat of the United States the Cuban government had no excuse not to liberalize its politics.

The two exile camps also differed in their understanding of the nature of the Cuban regime. While both claimed that Cuba’s government was totalitarian, those working to harden U.S. policies against Cuba believed that the government was about to fall at any moment, whereas those with ties to internal groups argued that the political situation was far more complex.

The controversy around whether or not to engage in dialogue with Cuba also touched on another topic: whether there was any possibility of genuine dialogue with the Cuban leadership and whether agreements reached through a process of negotiation and reconciliation would be respected. At the crux of the debate was a tremendous power struggle within the exile community as different factions and individuals positioned themselves for leadership. The essential question in this debate was what role, if any, the exile community should play in shaping the future of Cuba.

The move to reengage with the island was tempered by the force of those opposed to dealing with the Cuban government. The possibility of change in Cuba reenergized those advocating a traditional exile agenda. In the spring of 1991, for instance, in response to a realignment toward the political center within the émigré community, organizations opposed to a dialogue with the Cuban government staged a march in Miami to unite the exile community. Its agenda called for no dialogue with the Cuban government.45 Something similar occurred in the autumn of 1993, when more than 100,000 people marched to support a tightening of the blockade.

Both in Cuba and in the exile community discussion about the future of Cuba and U.S.-Cuban relations was extremely difficult. On the island, while broad discussion took place within the process initiated by the Communist Party, people were publicly encouraged to unite behind a hardening official position that made debate or dissent difficult. Human rights activists were accused of being agents of the U.S. government and were jailed under laws prohibiting the right of assembly. Across the waters the FBI named Miami the capital of U.S. terrorism, as eighteen bombs went off in the homes and businesses of Cuban exiles working to better relations with Cuba. At the same time, hard-line exile organizations accused advocates of closer relations with Cuba of being Castro government agents.

Those supporting better relations with Cuba were also limited by their narrow political agenda. While criticizing U.S. policies that created obstacles to normal relations between the exile community and Cuba, they were generally silent about Cuba’s divisive policies toward the exile community. This silence diminished the possibility of forming a Left-to-Center coalition in the Cuban-American community that could effectively challenge the Right.

The political center of the exile community included groups that favored democratization of Cuba and the community itself. Unlike the extreme Right, which had limited contacts in Cuba, many centrists, who were also advocates of human rights in Cuba, developed relationships with opposition groups on the island. These links had a significant impact on the politics of such groups, as they became much more in tune with what was actually happening in Cuba. In addition, these human rights supporters did not present themselves as Cuba’s future leaders but, rather, recognized that the island’s future must be built from within. Nevertheless, their closeness to U.S. positions allowed the Cuban government to delegitimize them by calling them pawns of U.S. policy.

Despite these constraints, this period provided relatively fertile ground for solving some of the issues that divided Cubans on and off the island. Generational changes were occurring both in the exile community and in Cuba. New arrivals brought a contemporary vision of Cuba and their relationship with their homeland to the émigré community. Miami, the city of political extremism, engendered the potential for a political culture of critical thinkers from Cuba and the United States who had not found entrance into mainstream institutions on the island or in the traditional United States émigré community.