LOCATION South of the Icelandic coast

NEAREST POPULATION HUB Reykjavik, Iceland

SECRECY OVERVIEW Access restricted: arguably the world’s most pristine natural habitat, unspoiled by human intervention.

The North Atlantic island of Surtsey is among the planet’s youngest places, having emerged from the sea during an underwater volcanic eruption that lasted from 1963 until 1967. The territory was quickly declared a nature reserve, and only a small band of accredited scientists has ever been allowed to land there to record how life on Earth spontaneously develops.

The infant island lies around 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) southwest of Heimaey, the largest of the Westman Islands. The first indications of a volcanic eruption underway here came on November 14, 1963, when changes in the surrounding water temperature, a rising plume of smoke and the smell of hydrogen sulfide were all observed. However, the eruption is thought to have begun several days earlier, some 130 meters (430 ft) beneath the sea.

The eruption followed the line of a tectonic fissure, and emerged from the sea in columns of dust and ash that reached heights of several kilometers. Within a week, an island had formed. It was named Surtsey, after Surtr the fire giant of Nordic mythology. Although the sea immediately began to erode some of its territory, continuing eruptions that added to the land mass more than kept pace. The island achieved its maximum diameter of more than 1,300 meters (4,300 ft) in the early part of 1964. Iceland quickly asserted dominion over it, and declared it a nature reserve.

By the time the eruptions came to an end in June 1967, Surtsey covered an area of 2.7 square kilometers (1 sq mile). It consisted of roughly two-thirds tephra (rock fragments thrown up during an eruption) and one-third rapidly cooling lava. While the tephra has gradually washed away over the years, the hard lava core has proved far more resilient. It has been estimated that the wind-battered island will not be returned to the sea before 2100 at the earliest, and it may survive for several centuries. However, two smaller sister islands that appeared during the original eruption were soon eroded to nothing by the Atlantic waves.

Scientists were quick to realize that Surtsey offered a unique opportunity to study geological and biological evolution on virgin land. If man can be kept at bay, the island’s remote location means there are few threats to its well-being other than the sea itself. The first vascular plant was discovered as early as 1965, although the first bush, an altogether more complex and demanding form of plant life, was not to appear until 1998. The island’s poor-quality soil was quickly improved by the guano from birds that started flocking there around 1970. The first resident bird species were the fulmar and guillemot, and the soil can now support complex life forms, such as earthworms. Seals started breeding on Surtsey in 1983.

As for humans, landing on the island is strictly forbidden, unless you are a scientist who has been awarded a permit by the Surtsey Research Society, which supervises all activity on the island on behalf of the Icelandic Environment and Food Agency. Diving in the island’s environs is not allowed, nor is disturbing any of its natural features, introducing any organisms, soils or minerals, or leaving any waste. It is also forbidden to discharge a firearm within 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) of the coast.

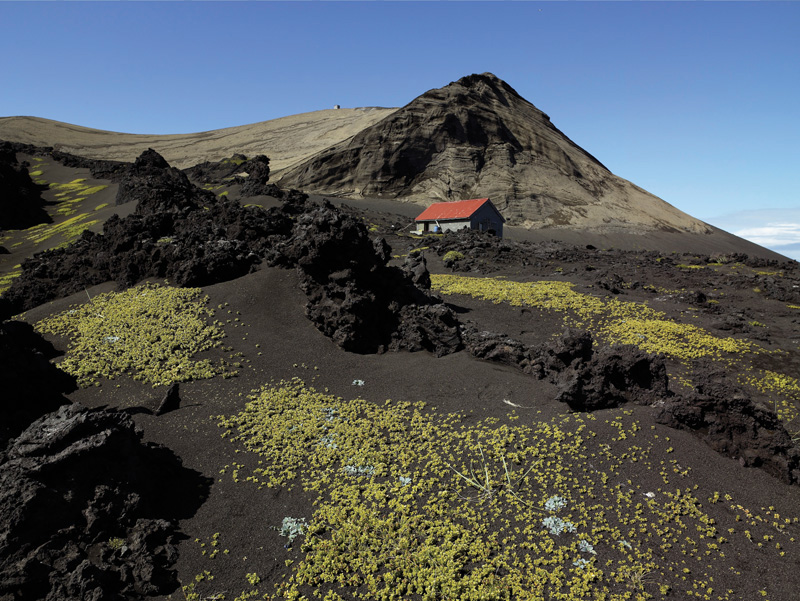

LONELY OUTPOST The only concession to mankind on the island is a rudimentary hut that serves as home to visiting scientific personnel. It is administered by the Surtsey Research Society, which works hard to ensure that the landscape remains unspoiled for the species that have gradually colonized it.

While most of the species so far found on Surtsey have clearly been brought here by natural “vectors,” human-imported crops were discovered (and promptly removed) on two occasions during the 1970s. In the first instance, a tomato plant was found: it is thought that a researcher must have had a hearty lunch and then been caught short, prompting an instance of unregulated seed dispersal! In 1977 a crop of potatoes was discovered dug into the ground, and the finger of blame was firmly pointed at some spirited young boys from the nearby Westman Islands who had rowed out to Surtsey during the spring.

The island was inscribed on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites in 2008. By 2004, the assorted life recorded on the island included 69 vascular plants, 71 lichen, 24 fungi, 14 bird species and 335 species of invertebrates. In 2009 it was widely reported that a Golden Plover was found nesting on the island, the first wading bird to do so. Each year, somewhere between two and five new species are discovered.

The one nod to human comforts is a basic prefabricated hut where scientific researchers are stationed. It contains little more than a few bunks, a solar panel to produce energy and a radio for use in emergencies. There is also a dartboard to provide entertainment.

1 VOLCANIC ISLAND Surtsey’s geography has changed considerably since it first emerged from the sea. For instance, it lost about a meter in height in the 20 years following the original eruption. The island is still subject to volcanic activity, as evidenced in the close-up photo.