AS is readily deduced from inspecting mountains with the idea of climbing them, some routes are all rock, others all snow and ice, and many are a combination. A safe ascent of a route involving snow and ice requires a familiarity with, and a respect for, the substance. You must also have the proper equipment and know how to use it.

People who would never think of climbing a cliff, or who have some understanding of rock but none of snow, seem to be easily fooled by the hidden hazards of snow and ice. Those who live in areas with cold winters know it is easy to slip on level ice but may have no conception of how much easier, farther, and harder they can fall when it is steep. Those who live in mild climates near sea level have provided a startling record of disasters on icy mountain slopes. Imbued with enthusiasm and ignorance. they rush out on snowy hillsides which are as pretty as Christmas cards – only to shoot off like toboggans to injury or death. Others. lightly dressed, set forth across snows that look innocent and beautiful on a springlike day, but lose their lives in sudden storms.

Safe Climbing on Snow Bnd Ice

An elementary knowledge of proper equipment, clothing, and techniques would avert many such accidents, both among non-climbers and would-be climbers. If you are well versed in basic rock climbing techniques, you have a head start, though there is no reason other than geographical chance or personal preference for taking up one phase of climbing before the other. In fact, the two can be learned simultaneously, and some of the techniques are very similar. As in rock climbing, snow and ice techniques are best learned through instruction and practice with able and experienced individuals or groups, or in qualified courses or schools. Reading is helpful, but is no substitute for workouts under skilled instructors. Beginners should start their practice on snow. or on snow that has a frozen icy surface; this is the limited meaning of “snow and ice” as used in this chapter.

To start rock climbing, you can turn up in some old clothes and climb, but for snow, you must have the proper clothing and gear. If you wish to try equipment out before buying, it can be rented from a mountaineering shop, borrowed from a friend, or provided by a commercial climbing school or guide service. However it is acquired, its selection and care is similar.

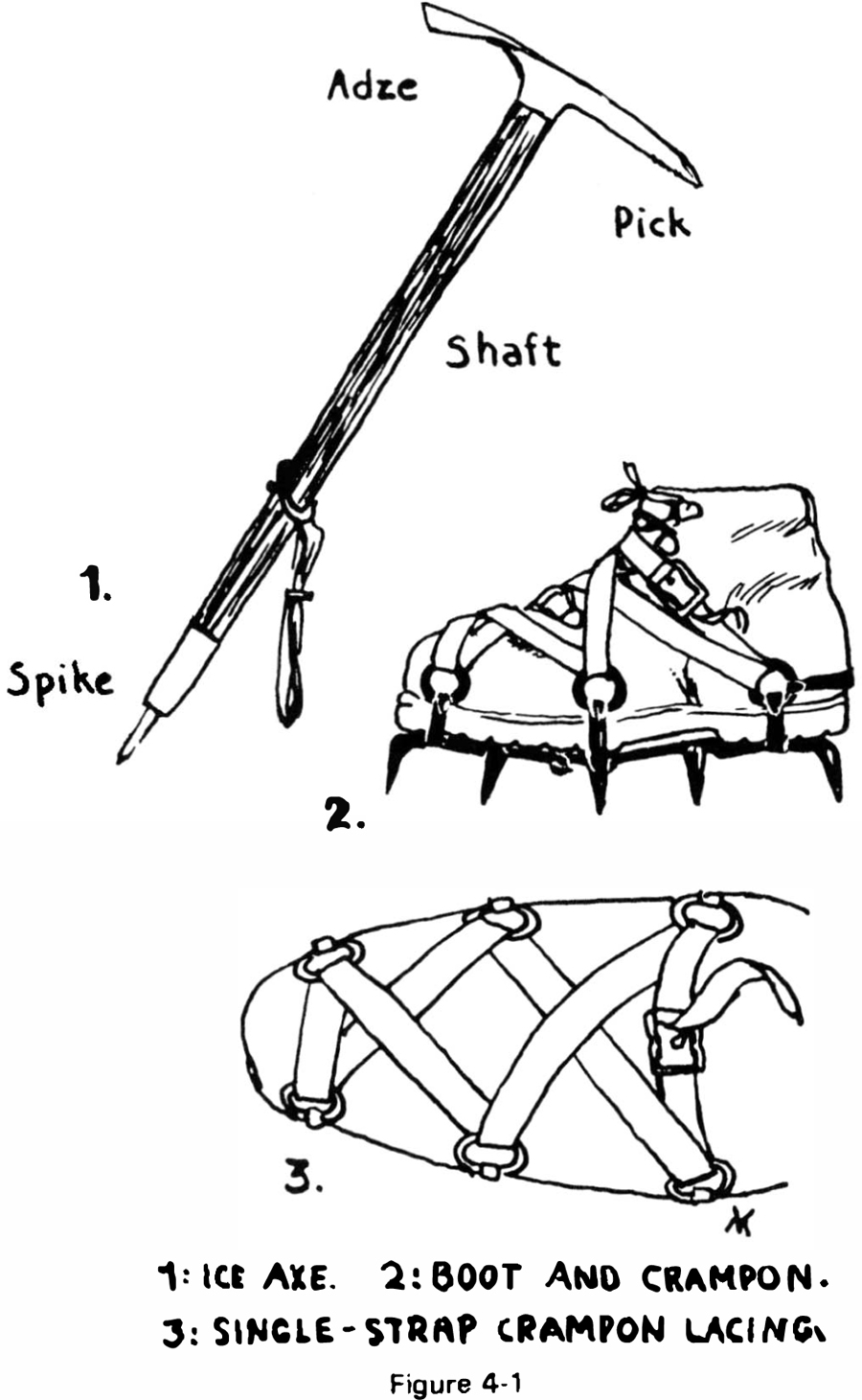

Ice Axe

A special-purpose tool exquisitely designed for safeguarding and assisting the traveler on steep snow and ice. Most are imported from Europe and Japan. The axe, as illustrated in Figure 4-1, has a wooden shaft, oval in cross section, about twenty-six to forty inches long. At one end of the shaft is a steel point or spike; at the other end is a head between ten and twelve inches long. It consists of a sharp pick, and a blade or adze which is either flat or slightly curved. Most axes have a wrist loop made of three-quarter-inch webbing or leather attached to the shaft by glide ring. A metal stop, nine or ten inches from the tip, keeps the glide ring from falling off.

Despite differences in style, details, and prices, any standard ice axe gives good service. Do not buy one with a small, substandard head. Choose an axe of sturdy workman-like construction, and pay particular heed to the shaft. Though hickory is regarded by Americans as tops for tool handles, Europeans use ash (having no native hickory trees). A straight close grain, free of knots, should be chosen. As to length, select an axe that feels comfortable in the hand as a staff. Too long a handle is awkward on steep slopes and is a nuisance to carry; some excellent climbers recommend a very short axe regardless of the person’s height.

The shaft is sometimes wrapped, for three or four inches above the point, with vinyl tape to save the wood from excessive abrasion. Occasional sanding and a light rubbing with hot boiled linseed oil will protect the handle from water. If the shaft breaks, it can be replaced. The wrist loop should be checked occasionally for wear. and replaced if necessary. Store the axe in a dry place. Your living quarters are ideal – and quite practical, as an ice axe is not only useful but decorative.

Boots

Important to protect the feet and give proper traction on snow. The best boot is a European (or European type) mountaineering boot, six or sometimes eight inches high, padded under the lining with foam rubber. The sole has rubber lugs, whose great utility lies in their adaptability to snow and wet or dry rock. Nylon or waxed cotton boot laces are best.

The boots should be large enough to be worn over at least two pairs of heavy wool socks, and still leave room to wiggle your toes. They should have hard box toes to protect the feet when kicking steps and when crampons are strapped to the boots. Waterproof construction is essential; look for a water welt, a very narrow strip of leather sewn to the uppers and the sole. The tongue should be sewn shut at least partway up, and many are sewn clear to the top.

Your boots must be cared for to maintain their water-proof properties and protect the leather. After use, let them dry slowly; stuff tightly with newspaper, which should be changed occasionally, or use a boot tree while they are drying, to maintain their shape. Treat the leather with a thin liquid silicone; apply a second coat to seams and edges of the sole. Then rub in a coat of wax-based waterproofing (not grease or oil). Warm the boots before or after the application in the sun, next to a hot air register, or in an oven which has been heated to about 140 degrees and turned off before putting the boots in (setting them on aluminum foil protects the sales from the hot grill). Keep your boots in good repair, and store them clean and waxed in an airy place.

Crampons

Not usually essential for the strict neophyte, but a fundamental piece of snow and ice gear. As illustrated in Figure 4-1, they are assemblages of sharp metal spikes on a (usually) hinged framework which, when strapped tightly to the boots, provide stability on hard snow and ice. They come with ten or twelve points each (four-point instep crampons are not real climbing irons). Ten-point crampons are satisfactory for all-round use on easy to moderate climbs. Crampons with twelve points, two sticking out in front to kick into steep ice, are essential for advanced ice work. Good crampons are made from tempered steel, by forging. Army-surplus crampons are cheap but untrustworthy.

Boots and crampons must work as a solid unit; hence a good fit is essential. First choose your boots, and have them with you when you are buying or renting crampons. It should require some force to jam the boot into the crampon. The boot must not slip sideways; the crampon must be long enough that the front points are near the boot toe, but short enough so the front ring or hook of the harnessing framework is well back of the front end of the boot. A pair of crampons has a right and left, important for a perfect fit. Some crampons are adjustable for different sizes of boots.

The crampon is held on partly by the tight fit and a piece of metal that fits around the heel of the boot; and partly by a series of straps and buckles, or by a single strap five or six feet long. This may be a thong of leather or a strap of cotton or linen webbing three-quarters-inch wide. It must be long enough so there is an ample end to pull on when cinching it up tight over boots, socks, pant legs, and gaiters. Excess strap can be tucked in. Understand the method of attachment when you get your crampons. The standard method of lacing the long single strap is shown in Figure 4-1 . Minor adjustments for fit are possible, but must be made with great care lest the metal be weakened or broken. Keep crampons free of rust. File the points sharp again if they become dulled. Check the straps occasionally, and replace if signs of wear appear.

Rope

Essential in ice work, but the beginner is not expected to supply it while learning. Exclusively for snow and ice work, a 60-foot, 3/8-inch Goldline would be adequate for two people. However, anyone expecting to do much climbing should have an all-purpose rope at least 120 feet long, and 7/16 inches in diameter, that can be used for two people on both rock and snow and for three people primarily on snow and glaciers.

A rope that has become thoroughly soaked or even superficially wet should receive special attention at the end of the climbing day. It should be uncoiled, and dried under natural conditions (not by the campfire!). Kinks should be removed, both before and after drying. It should be re-coiled for storage.

Ice Pitons and Screws

Employed primarily by advanced climbers, for protection on difficult ice climbs. Intermediate climbers may want a few along for practice, for protection on an unexpectedly steep or icy slope, or for emergencies in which an anchor is necessary and possible. Keep in mind that ice pitons will usually hold only a fraction of the strain that a rock piton can withstand. Superior protection is obtained where it is possible to drive rock pitons into sound rock walls.

Ice pitons are generally between six and twelve inches long and have large eyes. Some resemble large rock pitons. Some are tubular, with or without threads; and some are made like very long, rather thin screws. A hammer, or a short axe with a hammer head instead of an adze, is needed to drive the unthreaded pitons and to start the screws. The screws can be turned, after starting, with another piton or the axe point inserted in the eye for leverage. If possible, ice pitons and screws should be placed at an angle slightly uphill from the perpendicular to the line of potential pull. Snow pickets, aluminum tubes about four feet long, are sometimes carried for use as pitons by parties expecting quite difficult snow passages.

Adequate clothing must be available for protection against cold, damp, sudden storm, temperature extremes, and exposure to sun.

Underwear

Wool, or part-wool and part-cotton, is the best material. Dacron, down, and the like insulate well while dry; cotton “fishnet” underwear is intended for use under such materials to allow perspiration to escape. But only wool continues to feel warm against the skin even when it has gotten wet (from inside or outside). Underwear with long legs is essential unless the outer pants are of wool, and is sometimes needed even then. Separate uppers and lowers are more adjustable to changing temperatures than one-piece outfits.

Pants

These should be of a hard-weave material that does not collect snow. Wool, part-wool, and nylon are good. Heavy cotton is all right if it is water-repellent (denim is unacceptable). Be sure your pants are baggy enough for freedom of movement. Knickers, often corduroy, are popular, especially in the summer (although corduroy gets wet easily and dries slowly). Trousers should taper toward the feet, and should be held down by an elastic under the instep or tied around the ankle with a drawstring.

Socks

All-wool is the only suitable material, except for a little nylon reinforcing. It is usual to wear at least two heavy pairs, with a light soft pair (which may be nylon or fine wool) next to the foot to reduce friction if blisters are a serious problem. With knickers, wear one pair of long socks that reach to the knees or above them. Spare dry socks must be carried on long climbs, as wet socks promote frostbite.

Gaiters

Essential to keep snow out of boot tops. A compact, efficient type is four to eight inches high, tubular with elastic at top and bottom. For deep snow, they should extend up to just below the knee. Short gaiters are of nylon or water-repellent cotton, with or without a side zipper. Long ones, of heavy-duty material, usually have hook lacings. Instep cords or straps hold the gaiters down; to prevent cutting these straps, do not fasten them until you are on snow. Gaiters are also useful to keep gravel out of boot tops.

Shirts and Sweaters

Several lightweight layers (instead of one heavy one) permit you to add or subtract garments as temperature vascillations require. Since a snow climb can be extremely hot, the bottom layer is often a cotton T-shirt or a long-sleeved cotton shirt that is cool but protects against sunburn. Other shirts and sweaters should be woolen.

Parka and Poncho

A generously cut, windproof, water-repellent parka is a necessity. It can be worn as a light jacket, or it goes over the woolen garments when wind, cold, or precipitation requires. It should have many pockets, and a hood is essential. Choose a sturdy cotton poplin or a cotton-nylon weave, with or without front zipper. You can rewaterproof your parka when necessary with a wax-emulsion solution or a spray-can compound; or have a dry cleaning establishment do it. A lightweight plastic poncho is useful in case of summer rains or sloppy snowfall too extensive for the parka to cope with. A cagoule is a sort of hybrid parka-raincoat, long enough to keep the pants dry but too long to climb in.

Down Clothing

Down jackets and trousers are very warm, very expensive, and not needed for the type of trips that the beginner goes on, although marvelous on expeditions and winter ascents, etc. Extra wool socks are far more versatile than down “bootees” for ordinary climbs.

Hat, Cap, Mittens

Helmets and hard hats are coming into use in snow and ice work; they provide protection against head injuries suffered from falling rocks or from crashing into rocks. For beginning practice trips, it is sufficient to wear a felt hat with a brim for sun protection. A woolen cap should be available, as much warmth is lost through the head. A pair of woolen mittens (warmer than finger gloves) should be carried. An extra pair, and/or a pair of nylon or water-repellent canvas “covers” should be taken on all trips longer than a few hours.

Sun Protection

Sunburn is an acute problem on snow because of reflection, especially at high elevations. Goggles or dark glasses are essential. A good sunburn cream (the popular beach types are inadequate) can be had from mountaineering shops or pharmacies. Special preparations are manufactured for the lips, which are especially sun-sensitive. Clown white (actors’ grease paint) or zinc oxide ointment give almost complete protection for people who sunburn severely. Remember to apply the goo to areas affected by reflection, and to re-apply as often as needed, especially around nose and mouth.

As a neophyte suitably clothed and outfitted, you are far better off than an unequipped visitor to the snow slopes. You must, however, practice the proper handling and use of your equipment under able tutelage. The group or individual giving instruction should select a safe practice slope, its steepness correlated with the texture of the snow. It must have a safe runout, without rocks, trees, or precipices at the bottom. This easy slope will ideally allow you to practice all the techniques basic to safe snow and ice climbing.

Aside from proper boots, the ice axe is the sine qua non of snow and ice climbing. It is in constant use whether or not rope and crampons are needed. The major functions of the axe’s parts are these: (1) Point or spike: used like the bottom end of a cane in walking, or to drive into the snow for stability when climbing. (2) Adze or blade: for cutting steps in hard snow. (3) Pick: for cutting steps in ice, for selfarrests when falling, or to jam into steep snow so the axe handle can be used for balance. (4) Shaft: to use as a staff, and as a belay point for the rope.

The many uses of the ice axe are mastered with practice, and during this practice its three sharp parts must be recognized as dangerous and be treated with care and respect.

Transporting and Carrying the Ice Axe

While not in use, the axe is often equipped with a rubber guard over the point, and sometimes an adjustable sheath for the head. To carry the axe when walking, hold the shaft at the balance point. Carry it parallel with the ground, point forward and head backward with the pick pointing down. It may also be tucked under one arm in this position. When the axe is used as a walking stick, the head provides comfortable support for the hand, with the pick facing forward.

Wrist Loop

Used only in places where the axe is essential to safety, yet would be lost if dropped. The clasp slides to tighten the loop after the hand is inserted. Some excellent climbers are against wrist loops, claiming the axe might injure you if attached to the wrist, and should never be dropped anyway. These considerations, while valid, seem to be outweighed by the importance of having your axe when it is needed.

Walking up Easy Slopes

Walking up the practice slope is no problem, but it is the beginning of learning to climb on steep snow. Start straight up the slope, kicking your toes into the snow. Footsteps should be fairly close together to conserve energy and accommodate those with short legs who may be coming after you. Use the axe as a staff, with the pick backward. With the hand in this position on the head, the axe is ready for instantaneous use if a self-arrest is required. When the angle steepens, start to make switchbacks. Hold the axe in the up-hill hand; change it to the other hand when you change direction. On a slippery slope, stop moving and change the axe to the other hand before turning. Plant each foot firmly so the lugs bite into the snow; stamp or kick footsteps if the snow surface requires. Develop a gait in which you tend to drop your weight over the forward foot at each step. Keep your weight directly above your feet for balance; if you lean into the slope, your feet tend to skid out from under you. When several people ascend together, each should walk some little distance behind the other, all using the same footsteps and improving on them (it takes far less energy than for each to make his own steps).

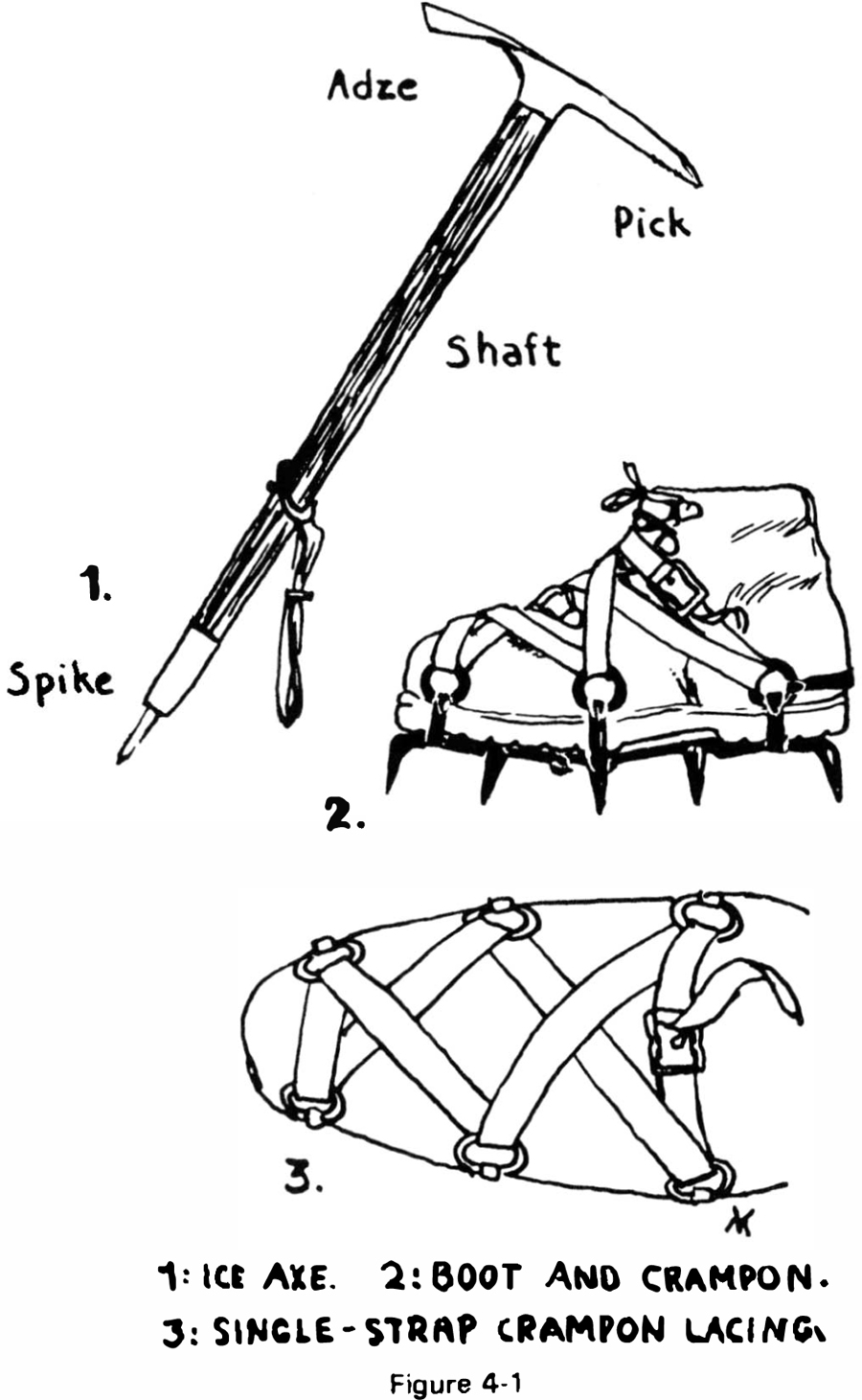

Self-Arrests

An important function of the ice axe is to slow or stop your own slide after a fall. It is a vital skill, whether you are roped or unroped. It is learned on safe slopes and soft snow. Protect yourself from sharp ice particles with long sleeves and mittens. Hold the axe in the arrest position, as follows: Hold the axe head near your shoulder, with fingers over the head and thumb under the adze. The pick points forward so it will dig into the snow when you fall on the axe. The shaft is held diagonally across your chest with the other hand grasping it near the tip. The tip is held near your hip.

Next, lie facedown in the snow, with the axe under you, as shown in Figure 4-2. Let yourself slide downhill feet first; arch your back slightly to press the pick into the snow under your shoulder. The friction of pick in snow should gradually stop your fall. Repeat on increasingly steep or fast slopes. On fast crusty snow, start the pressure at once, but drive the pick in gradually and take care not to let the point catch and flip you over. As the slide becomes faster, spread your legs for balance. In soft snow, dig in your knees and toes (and elbows too) to assist in the arrest; in hard snow brake with the toes of your boots in addition to the axe.

As a real fall is not always in a conveniently perfect arrest position, practice getting into that position from various awkward starts. Start sliding on back or side; curl your body a bit and roll over quickly toward the side on which you are holding the axe head. Start down head first, on your stomach; dig in the pick; and to get your legs downhill, swing them around the pivot formed by the pick. Start down on your back, head downhill; roll onto your stomach and then pivot into the feet-first position. And act quickly, before you get going too fast.

When you start climbing potentially dangerous slopes, always note the consequences of a slip. Observe the gradient and texture of the snow, and the length and nature of the runout. Mentally rehearse the motions for a quick self-arrest.

If self-arrests always worked, there would be no need of a rope. However, on slopes very soft, very hard, comparatively steep, or with dangerous runouts, the climber cannot always stop himself soon enough, if at all. Hence, as on steep rocks, the roped team is used for mutual protection.

Roping Up

The preferred number of climbers on one rope for snow and ice is three. A shorter rope is used than in most rock climbing; 120 feet for three people is standard. If the ’available rope is longer, or if only two are tying into a 120-foot rope, it can be shortened. One climber ties to the end of the rope with the usual bowline, but leaves about two feet extra at the end. The unwanted portion of rope is wound diagonally around the chest, over one shoulder and under the opposite arm. The coil is then secured with a bowline-on-a-coil tied with the rope end saved for that purpose (see Fig. 2-3). The middle man should not use the butterfly knot in snow work, as it jams when wet. The easiest substitute is the double bowline, tied like a standard bowline but using a doubled section in the middle of the rope, as illustrated in Figure 2-1 .

Methods of Climbing

As in rock climbing, the best climber goes first, and the least experienced last. There are two methods of progress, continuous and consecutive (both also employed on rocks of ease or difficulty).

Continuous Climbing. Used where a fall can be stopped even though the climbers are in motion. The rope is needed for protection because of crevasses on a glacier, and/or steepness. All those tied together walk at the same time, each adjusting his pace to the others. They are far enough apart so there is little or no slack in the rope between them, except that each climber holds one or two coils of rope in his free hand, to help adjust his pace to the others and to allow a slight warning in case of a fall. Each climber should have an ice axe (a beginner will feel he has too many things in his hands). When one climber changes direction at the corners of the switchbacks, and has to change the axe and coil to opposite hands, the others should wait until the transfer is complete.

Consecutive Climbing. Used when the ascent is steeper, the snow icier, or the terrain below dangerous – and where it would be hard to hold a fall without being set for it. Only one climber moves at a time while the other two belay him. The sequence of climbing is much like that of multi-pitch rock climbing. The leader goes up a rope length; he brings up the second and climbs another rope length ; and the second brings up the third before joining the leader.

Rope Handling

In handling the rope on snow and ice climbing, due allowance has to be made for moisture and temperature. In cold, dry weather on hard snow, the rope may stay dry even if dragged all over the snow. If the snow is deep or wet, the rope is almost sure to get wet sooner or later. You can put this off a little by trying to keep it out of the snow when climbing continuously, perhaps hanging your coil on the axe head instead of laying it in the snow, etc. The wetter the rope, the harder it is to handle because of weight and friction. More moisture is transferred to clothing, especially mittens. Knots are harder to tie and untie in a wet rope. When the temperature drops, the rope freezes and gets slippery, stiff, perhaps covered with hoarfrost. When it does get wet and frozen, endure it.

Establishing a solid belay is more difficult on snow than on rock because of the slippery and unbroken nature of the climbing medium. A hip belay, as in rock work, can be given if the belayer is well braced in depressions, holes, small crevasses, flat places, or on various stances manufactured with the axe. However, the usual stopping place consists of two footsteps. The ice axe jammed into the snow is then used (something like an anchor piton and carabiner) as a fixed object around which the rope is passed. A simple belay around the axe shaft may serve when the axe is especially stable. Much stronger is the boot-axe belay.

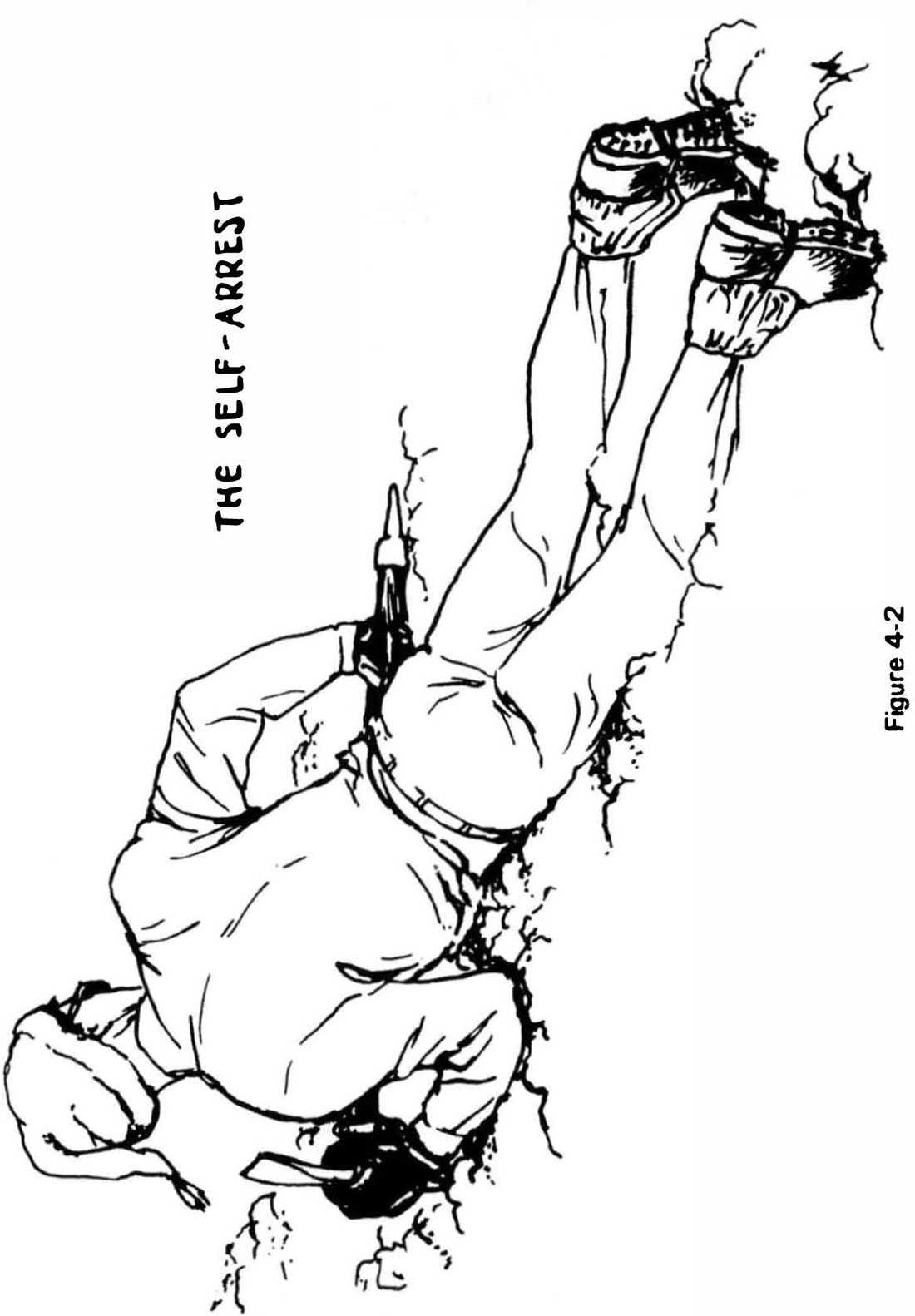

Boot-Axe Belay

The ice axe and the boot work together to establish a belay point which is unlikely to be jerked out of the snow, and which provides much better friction for the rope than is possible with the axe shaft alone. The belay position is pictured in Figure 4-3. To give the boot-axe belay: (1) Stand sideways to the slope, facing in the general direction of the person climbing. (2) Kick or cut two sound and ample footsteps, one uphill and slightly in front of the other. (3) On the uphill side of the upper footstep, drive the axe as far as possible down into the snow, with the pick pointing uphill. (4) Plant the outside of the uphill boot firmly against the downhill side of the axe shaft. Place the downhill foot in its footstep. (5) The rope that comes from the climber should be passed over the toe of the boot; around the axe handle; then downhill between the axe handle and the instep; and back uphill toward the boot heel, as illustrated. The belay rope is held in the downhill hand. For holding a fall, friction is increased by moving the belay hand backwards and uphill above the ankle (hence this boot-axe arrangement is called the S-bend, to distinguish it from other positions that give less friction). When the position is fully understood, you can apply it very rapidly by jamming the axe point into the snow in the proper relationship to the rope, and stamping your foot against the shaft almost simultaneously. (6) As the uphill hand grasps the axe head, lean over the axe so your weight holds it down into the snow.

Belay Practice

Falls should be held for practice as in rock climbing. Start by belaying the climber who is coming up from below. You have to take your hand off the axe to pull in slack; but this hand is immediately returned to the axe head, with your weight over it, if a fall occurs. Increasingly sever falls should be tried. Belay the leader in the same position as when giving an upper belay. Remember that the shock will be greater. In choosing your stance consider the direction in which he will fall, and where he will hang when you catch the fall. The principle of the dynamic belay should be applied by letting the rope run a bit – you cannot help it if the jolt is severe – to lessen the shock on the axe.

Team Belays

In snow climbing, no one person on the rope is completely responsible for holding a fall. The person falling should immediately go into a self-arrest. Others on the rope should always belay, or be poised to belay, anyone who falls. Sometimes one climber has to catch two or more who are falling together. Whenever the cry “Fall!” is heard, others on the rope go instantly into a belay position if they are not already in it. The ascent of increasingly difficult slopes becomes relatively safe with known techniques of rope protection, belays, and uses of the ice axe.

As steeper slopes are climbed, on snow that is icier, or deeper and softer and less stable, methods learned and practiced so far are applied with greater finesse. The axe is used not only as a staff but as a sort of handhold when needed. In soft, unstable snow, the shaft is sunk deeply on the uphill side at each step. In especially precarious places, it is moved from one hole to the next only while the climber is standing still. Where the snow is hard or icy, either point or pick may be used on tbe uphill side for balance or for a slight purchase. The axe is used also to feel and probe the snow for changes in texture. Where kicking footsteps becomes arduous or ineffective, the adze can be used to cut footsteps. Care to maintain perfect balance is compulsory. Crampons are still another specialized piece of equipment to lessen the effort and hazard of ascending steep snow and ice.

Your first try at walking up a crusty snow slope on crampons is apt to be wildly successful! The points bite crisply into the glittering white surface and your footing seems secure beyond human possibility. But as with other climbing equipment, crampons must be properly used to get the greatest benefit from their beautiful design, and to avoid inherent hazards.

Storage and Transport

The points of crampons are dangerous, and must be treated as such to prevent injuring yourself and others. They also must be protected to keep them sharp. Cover the points when out of use, and be careful when wearing them. Store crampons in a box, at home or in the car. On the pack, use bought rubber crampon protectors, or lash the pair pointsdown to opposite sides of a board or a rectangle of styrofoam. Corks, or sections of rubber tubing, can be stuck on all the points instead.

Learning to Walk on Crampons

You should have a frozen surface with a fairly gentle gradient to practice on. To put on the crampons, sit down where you can lay them with points down on the snow, and install first one and then the other. Straighten out the harness, shove your boot into the framework, and lash them tightly to your feet. Adjustment of the straps is usually necessary after walking a short distance. Make sure they are tight enough not to slip, but loose enough across the instep not to cut off your circulation. Take each step with the crampons flat on the snow surface. This requires great flexibility in the ankles. Place the foot down firmly and precisely with each step, stamping slightly or letting your body weight fall forward over the foot if necessary to drive the points into the snow. When taking a step, raise each foot high enough to prevent your tripping on the points.

Cautions in Crampon Use

One of the hazards in cramponing is the possibility of catching the points on the clothing of the opposite leg. You may tear your clothes or your hide, or trip yourself. To prevent this, wear pants that are not too full in the legs, wrap baggy pant legs with cord, or wear confining gaiters. Knickers and long socks lessen but do not eliminate this hazard. Also learn to walk with your legs slightly apart. Perfect your balance. If you do fall, remember that the points may puncture someone, maybe you. In making a self-arrest when wearing crampons, bend the knees somewhat to avoid catching a crampon point and being flipped. Never step on the rope with crampons. In soft snow, watch out for the balls of snow that may form between the points. Knock them loose with a tap of the axe, or a kick with the side of one foot against the opposite boot.

Cramponing on Increasingly Difficult Slopes

Crampons are often used for convenience on hard snow that is quite flat, but their greatest use is on steep, icy slopes. Once put on for a climb, they are often worn all day long, even on sections where the snow or slope becomes easy, to save the trouble of removal and re-installing, But it is customary to take them off for all but the shortest rock passages, to protect the points from dulling or damage. You will probably not encounter really long, steep, icy slopes in your early climbs. But it is a somewhat relative matter; what takes all your skill and nerve during your first summer may seem easy in a season or two. As the slopes you climb become steeper and icier, be especially attentive to balance. Both feet and body are positioned somewhat as in friction-climbing on rock. Stamp the crampons flat to the slope and coordinate the use of crampons and axe; also pay close attention to belays and possible self-arrests. When the slope seems too icy or too steep for you to trust the bite of your crampons, the rope leader (or you yourself) can provide an additional safeguard by chopping steps. Up till then, the leader may have saved time and effort by cutting steps only at belay spots. Enjoy your crampons, perfect your mastery of them, and learn to trust them on both the ascent and the descent.

The descent of a given slope is usually made in much the same manner and with the same equipment and protection as the ascent if conditions remain the same, but with even greater care, since the descent is often more awkward, and sometimes snow conditions are worse.

Climbing Down

If a steep ascent required careful climbing, the descent probably will too, though snow may be better or worse. The party uses the same footsteps if possible. The leader goes last in a roped party. Snow that was soft on the ascent may have grown icy, or hard snow may have softened and be poorly consolidated. The first person down should if necessary improve the old steps, or cut or kick new ones.

Walking Down

If the snow is soft and the slope fairly easy, nothing more specialized is required than walking down. Even this should be done properly, to perfect techniques and save energy and time. When you are going straight down, let your weight come down on your heel at each step, to drive it into the snow; keep your foot bent toe up so the heel hits first. You are least apt to slip out of this type of step. If the slope seems rather steep or the snow poorly consolidated, take each downward step with deliberate care, using your axe at your side as a staff held in both hands. On such a slope, the party may be roped but walk a together. If the snow is more reliable in texture, let.each heel slide for a couple of feet in the “plunge step.” This increases the speed and ease of descent. Under ideal conditions, you can run down a slope safely with the plunge step, holding the axe in arrest position.

Glissading

Glissading is a speedy, restful, and wonderful way to go down, when texture and gradient are just right. It is also potentially dangerous if you misjudge the slope and conditions. Practice on short slopes with obviously safe runouts. Gradually work up to longer and faster slopes. But always look for a safe runout as a safety measure if you should lose control, for instance by hitting an unexpectedly icy spot. It just isn’t healthy to end a glissade in a rock pile or by shooting over a cliff.

Glissades are made sitting or standing. The sitting position is safest and easiest. To get ready, remove your crampons and stow them safely; batten down your clothing and put on mittens; hold the axe in arrest position, with the wrist loop on. Sit down with knees straight and take off. The point of the axe can be used in the snow at either side for a rudder to aid in slight changes of direction, or to slow you down a bit. If you want to stop, dig in your heels and your axe point, or roll over in a self-arrest. A major change in direction, to avoid obstacles below, must be accomplished by stopping, and traversing on foot to a new starting point. On quite soft snow, pillows of it may form under your behind; hunch over them. Rough terrain or small rocks may be rather bruising. The most uncomfortable effect is getting your clothes wet. If keeping dry is important, walk or make a standing glissade.

A standing glissade is done with more style and aplomb, and is suited to steeper slopes when sufficient experience and judgment have been gained. It is more strenuous on the legs too. It resembles skiing on the feet, with the axe (loop on wrist) used to one side for support and steering. The standing glissade must be undertaken by the beginning climber with great caution, and first used only on short slopes to get the feel of it. Good judgment of snow conditions in relation to the gradient, as well as skill at keeping the glissade under control, is required for all gliss’ading that is done safely. And never fail to consider the runout.

Use your equipment until it no longer feels awkward; work on basic techniques until they become automatic both on practice slopes and on easy climbs. You are then ready to concentrate on the multitude of other factors which contribute to proficiency and judgment in ascents and descents on snow, ice, and glacier climbs.