Chapter 5

In a Fighter Squadron the Fighting spirit must be predominant. It is aggressiveness; it is an understanding of the word “duty”; it is a man’s pride in his work—whatever it may be—it is sacrifice; it is the ultimate conviction in a man’s heart that he, as a man, has a job to complete before he can rest; and at present that job is winning this war.

—Maj. Marshall Cloke, The Building of a Fighter Squadron

Replacement pilots Kocour, Hanna, Jennings, Highsmith, Vardel, and Knepper began the long rail journey eastward from Berrechid toward the Tunisian airfields that housed squadrons flying P-38s. Leaving on June 5, 1943, and boarding the same chain-cars that had brought them to Berrechid, their route took them on a northerly course through Morocco, passing through Casablanca, Rabat, Fez, and Taza. At Oujda they crossed the border into Algeria, trundling back to Oran, through the mountains toward Constantine and arriving at the headquarters of the 5th Bomb Wing at Chateaudun-du-Rhumel Airfield in northern Algeria on June 9.1

The replacement pilots received their final squadron assignments at Wing HQ. Catching transport from Chateaudun-du-Rhumel, the pilots made the 26-mile drive to their new base at Telergma.

Reporting to the 14th FG

Arriving at Telergma, Knepper and Kocour would have first reported to the group commander, Col. Troy Keith, and the group operations officer, Capt. Richard Decker. Being assigned to the 49th squadron, they would have next met the squadron commander, Captain Newman. They received their tent assignments, stowed their gear, and began meeting their tentmates and fellow pilots.

For the pilots who were already with the squadron, Knepper and Kocour’s arrival caused no great stir. They were, on average, just eleven missions in to a fifty-mission tour of duty. In the prior six weeks, they had seen several of their close friends lost in combat, and their focus was on getting through the next few months with as few additional losses as possible. In any case, it would be at least ten days before the “newbies” were fully combat-ready, and a few flights after that to assess their performance in combat.

Typical of the war during this time period, commanders were changed often. The standard tour for fighter pilots was set at 150 combat flying hours and fifty combat sorties, and this rule applied to group and squadron commanders as well as combat pilots. Colonel Keith himself flew combat missions, and when finally relieved three months later, had fifty sorties and two air victories to his credit.2

Captain Newman had previously flown with the 1st Fighter Group before joining the effort to rebuild the 14th. He had just completed his fifty missions, with more than 200 hours in combat, and was relieved the day after Knepper and Kocour’s arrival. He was replaced by the squadron’s operations officer, Capt. Henry “Hugh” Trollope. Trollope was chosen from among men who were surely his equal in terms of combat flight expertise and combat experience. His promotion to the demanding job of squadron commander was in recognition of his strong performance in operations, and of his capacity for leadership. Trollope would, as a first task, work to continue the esprit within the cadre of pilots that Captain Newman had achieved.

Beyond that, the squadron commander had wide responsibilities. His decisions would inevitably cost some of his fellow pilots their lives—pilots with whom he had already flown many combat missions. Pilots whose lives he may have saved in combat, and who may have saved his. The squadron was his to shape. He would review his squadron staff and consult with the key department heads—Engineering, Communications, Armament, Operations, Medical, and Intelligence. He might reassign some of the men of his command, even down to the lowest ranks, based on their physical and mental qualifications, and their experience.

If Trollope had been inclined to gather the pilots and admin officers for a meeting after he was named squadron commander, he might have reflected on the combat they had already seen and on how he gauged the squadron’s performance. He might have instituted new flight procedures or made changes to the squadron’s flight tactics. He might have let the pilots know what his policy would be regarding rest leave. He would have reminded the new pilots that their flying would all be done in daylight, and that with no runway lights or instrument approaches, it would be impossible for them to land after dark. He would have reminded all of the importance of checking guns, engines, and radio right after takeoff—and of the need to return to base immediately if any problems were found. He would have reminded them that an empty belly tank is full of explosive fuel vapors, and that if the tank did not release when the order comes in to drop, the pilot should turn around and go back, no matter how close to the target he was. And he would surely have confirmed to them that there was a lot of combat ahead as the Allies began the preparations for the next ground assault against the Axis forces.3

Concurrent with Captain Trollope’s promotion to commander, Captain Decker transferred from Group to become the new operations officer for the 49th. This move was significant, since it was the operations officer who made combat flight assignments and decided who would be promoted to flight leaders. As operations officer, Captain Decker would serve as primary administrative officer on the ground and would himself fly a full combat tour of fifty missions. On base, he would assist the commander in developing and supervising the pilot’s training program, including tactical instruction. It would be his responsibility to determine the qualifications of newly assigned flying personnel and recommend their assignment and training. Each week he would meet with the squadron’s flight leaders to apprise them of anticipated operations for the following week, having first liaised with the group operations officer. And he would meet almost daily with the squadron engineering officer regarding the requirements and availability of aircraft for the following day’s mission.

Like most of the other pilots who joined the squadron during its refitting in March, Trollope and Decker were just getting settled into their own combat roles, and now found themselves leaders of the squadron. While they knew their predecessors well, the learning curve in these new positions was steep, and both Trollope and Decker occasionally resorted to unconventional methods.

Captain Decker was very well-liked by his pilots and fellow officers. When vacancies developed through casualties or tour completions, it was Decker who decided which pilots would become flight leaders. Being named flight leader was important to the pilots, because it came with a promotion to captain, an increase in pay, and an opportunity for leadership. It was difficult to decide how these promotions would be made, since all of the pilots had arrived in theater at the same time, all had about the same number of flight hours, and all had about the same combat experience.

According to William Gregory, Decker had an unusual way of deciding who would receive the promotion: “It was kind of strange how Decker handled that. He was the ops officer. When a slot came open, he said, ‘Okay, we are gonna match for this,’ because we were even, as far as experience and time. He would [say] ‘Heads or tails.’ I lost three times, and it [being assigned to flight leader] meant a promotion to captain, so it was a significant thing. But I made it pretty early—we had a lot of turnover, so it came around pretty fast. It was a fair way to do it, and I thought Decker handled it very well. Decker was a good guy—I always liked him a lot.”4

In the brief thirty-four days since the squadron had restarted operations, the 49th had lost nine combat pilots out of their twenty-four-pilot cadre. Two, Lieutenants Bergerson and Green, had been lost on a dive-bombing mission to Milo aerodrome on the island of Sicily just four days previously. In the May–June period, the squadron lost more aircraft than it shot down. A tough reintroduction to combat.

There was no apparent pattern to the losses. Earlier in May, 2nd Lt. Burton Snyder had been lost on his first combat mission, and 2nd Lt. John Burton on his third. But very experienced pilots were also lost in the month prior to Knepper and Kocour’s arrival, including 1st Lts. Albert Little and John Wolford. Wolford, downed on his eighty-third mission, was already a combat ace when he was reassigned to the 14th Fighter Group to assist in its rebuilding, having shot down five enemy aircraft with the 1st Fighter Group. While half of the losses had come at the hands of enemy aircraft, one-fourth had been the result of flak, and one-fourth due to crashes and aircraft failures.

Risk is determined by exposure and consequence: The probability of an event happening is related to exposure, and for pilots this obviously meant that the more sorties they flew, the greater their chances of being killed. Squadron losses were especially high during the early days of combat. Many years later, 49th pilot William Gregory recalled: “There were times where we were losing so many, you get to wonder how long . . . I think [Lt.] Knott did a study one time, and he figured that the luckiest of us would have maybe twenty more days, or something like that. At the rate we were going . . . Of course it doesn’t work that way, because as you gain experience you become a better survivor. You think about [the odds of being killed]. You have to, because it’s real.”5

As it emerged from its rebuilding, the 14th FG reported seventeen pilots as missing in action during the month of May. Excepting Lieutenant Wolford, who was MIA on his eighty-third mission, the average number of sorties flown by the men who were lost was just under five.

The History of the 82nd Fighter Group records: “The Mediterranean was not a safe place for inexperienced P-38 pilots, and surviving their first few missions could be an accomplishment in itself. Of the twenty-one pilots assigned to the 95th squadron during the latter half of April, twelve eventually became casualties—nine of them during their first month.”6

The 37th squadron reported similarly. In its summary report for 1943, over the first fourteen missions (May 5–25), the pilot losses per sortie was just over 4 percent, and the victory-to-loss ratio was almost even: 1.28 to 1. Over the next six months, covering 159 missions, the loss rate was reduced to .21 percent, and the victory-to-loss ratio increased to 13 to 1.7

Over a one year period commencing with the restart of the 14th Fighter Group on May 6, 1943, the Group would lose 83 pilots: 23 before they had completed their 4th combat mission. The overwhelming share of losses—81 percent—occurred in the first half of the pilots’ combat tour. Pilots grew to understand that although the danger was inherent and unceasing, gaining combat experience was the best guarantor of survival.8

In the MTO, in the midst of the lead-in to Operation Husky, the number of sorties doubled between March and June, and Allied aircraft losses went from 117 to 256. During this period, the German air assets began to be degraded, but at a considerable cost. At the beginning of 1943, when German aircraft were contesting the skies in North Africa, the ratio of losses per sortie for fighter aircraft was four times the average for the war, as high as 5 percent in February 1943. But as the Axis forces began to be attrited by Allied forces, the risk associated with combat operations decreased to the average observed for the war, roughly 1 percent.

The lesson for the replacement pilots was stark: Losses were routine, expected, and largely unavoidable. The pilots learned quickly that these losses had to be taken in stride, insofar as possible, because the next combat mission was just around the corner, and would require their full concentration.

Trollope (left) and Keith.

STEVE BLAKE

Decker (right).

DELANA (SCOTT) HARRISON

The cohort of pilots at Telergma on the day Knep and Koc arrived were:9

|

Capt. |

William G. Newman |

Squadron Commander |

Goose Egg, WY |

|

Capt. |

Richard E. Decker |

Squadron Ops Officer |

Coffeyville, KS |

|

Capt. |

Lloyd K. DeMoss |

Flight Leaders |

Shreveport, LA |

|

Capt. |

Mark C. Hageny |

Hollywood, CA |

|

|

Capt. |

Henry D. Trollope |

Dewey, OK |

|

|

Capt. |

Marlow J. Leikness |

Fisher, MN |

|

|

1Lt. |

Wallace G. Bland |

Combat Pilots |

Hanceville, AL |

|

1Lt. |

Bruce L. Campbell |

Belgrade, NE |

|

|

1Lt. |

Lewden M. Enslen |

Springfield, MO |

|

|

1Lt. |

William J. Gregory |

Hartsville, TN |

|

|

1Lt. |

Harold T. Harper |

Bakersfield, CA |

|

|

1Lt. |

Carroll S. Knott |

Bakersfield, CA |

|

|

1Lt. |

William D. Neely |

Murfreesboro, TN |

|

|

1Lt. |

Wayne M. Manlove |

Milton, IN |

|

|

1Lt. |

Robert B. Riley |

Auburn, CA |

|

|

2Lt. |

Frederick J. Bitter |

Butler, PA |

|

|

2Lt. |

Beryl E. Boatman |

Okmulgee, OK |

|

|

2Lt. |

Sidney R. Booth |

McKeesport, PA |

|

|

2Lt. |

George B. Church |

Millington, MD |

|

|

2Lt. |

Aldo E. Deru |

Rock Springs, WY |

|

|

2Lt. |

Kendall B. Dowis |

Detroit, MI |

|

|

2Lt. |

Lothrop F. Ellis |

Germantown, PA |

|

|

2Lt. |

George J. Ensslen Jr. |

Germantown, PA |

|

|

2Lt. |

Anthony Evans |

Akron, OH |

|

|

2Lt. |

Martin A. Foster Jr. |

Harrisburg, PA |

|

|

2Lt. |

John B. Grant |

Topeka, KS |

|

|

2Lt. |

John M. Harris |

Yakima, WA |

|

|

2Lt. |

Walter L. Hoke |

New Windsor, MD |

|

|

2Lt. |

Monroe Homer Jr. |

Bakersfield, CA |

|

|

2Lt. |

Arthur S. Lovera |

El Monte, CA |

|

|

2Lt. |

Harry H. Vogelsong |

Toronto, OH |

|

|

F/O |

Charles W. Richard |

Lake Charles, LA |

During the next two weeks, other replacement pilots began to arrive:

|

2Lt. |

Joseph F. Cobb |

San Diego, CA |

|

2Lt. |

Eugene Churchill |

Unknown |

|

2Lt |

Edward J. Hyland |

Unknown |

|

2Lt. |

Raymond J. Kopecky |

Unknown |

|

2Lt. |

Donald Leiter |

Unknown |

|

2Lt. |

Louis D. Ogle |

Pierce City, MO |

|

2Lt |

John D. Sandifer |

Unknown |

|

2Lt. |

Wilbur E. Vardel |

Canton, OH |

|

2Lt. |

William R. Palmer |

Unknown |

Most of the 49th’s experienced pilots had been part of the original OTU—Operational Training Unit—that formed at Hamilton Field in California. These pilots had lived and trained together for over a year, and many had come to be close friends.

Many of the pilots might have considered that they had dodged fate in getting this far. Training accidents claimed many of their peers, and several of the 49th’s combat pilots had close calls before ever leaving the States. Lieutenants Bland, Lovera, and Flight Officer Richard had each totaled a P-38 shortly after receiving their pilot’s rating. Lieutenant Evans had destroyed two P-38s in the latter days of his training, and badly damaged a third in a takeoff accident. But the worst pre-combat record belonged to the group commander, Col. Troy Keith, who destroyed two aircraft and badly damaged two others in training accidents dating back to 1936.

With the addition of the new cohort of replacement pilots, the 49th squadron’s thirty-eight-pilot roster actually exceeded the number specified by the army’s table of organization for a twin-engine fighter squadron. The higher staffing was undoubtedly due to the high losses that had been incurred by all fighter units in North Africa during the first half of 1943 and to the army’s clear understanding of the unavoidable losses that would doubtless occur in the coming weeks.

Each squadron included a flight surgeon to oversee health care for all members of the squadron. For the 49th it was Capt. Lester L. Blount, his staff sergeant John Lawson, and seven other enlisted personnel, who treated over 1,000 patients during the summer of 1943. In addition to treating the normal colds, coughs, sprains, and broken bones, that summer Captain Blount had to deal with a serious outbreak of intestinal disorder. An average of 62 officers and men were down with “intestinal disease” each month during June, July, and August, and a total of 250 pilot days were lost due to disorders.

“I’m not sure how sanitary the food was [on base],” Lieutenant Gregory noted. “We all got dysentery, and we all lost weight. I think I weighed 118 to 120 pounds, and we had a lot of stomach problems because of food.” He believed that the pilots were showing signs of battle fatigue, due primarily to illness. “We had dysentery a lot, and it was just fatigue from the activity, and the poor food, and insufficient rest.”

Blount was well-liked by the squadron, and could be counted on to provide a medicinal dose of fruit juice and ethyl alcohol to pilots returning from a particularly difficult mission.

Captain Blount and his team of enlisted assistants had also shown a readiness to provide medical care to the local populace. In April, as the squadron was making final preparations to return to combat, Captain Blount was photographed administering to the son of a local Moroccan tribesman.

49th Squadron Flight Surgeon Capt. Lester Blount, here ministering to an ailing Arab child, often dispensed vitamins from his personal supply to residents of communities near the squadron’s base.

Capt. Lester Blount, Lubbock Avalanche, May 28, 1943. Originally published in the New York Times, April 28, 1943.

In the accompanying article Captain Blount was termed a “wizard of improvisation.” With the help of Sgt. Lawson—an ex-gold miner from Nome—Blount directed the excavation of a large hillside dugout at one of their temporary bases, lining the walls with spent five-gallon fuel cans packed with rocks and sand to create a bomb-proof structure. Later, he crafted an autoclave out of an old P-38 belly tank which he used to sanitize surgical instruments.

Flight Surgeon Blount was also doing his best to ward off malaria. All squadron members were issued a “mosquito bar”—a cloth mesh that was hung above the cots—and everyone was required to take a daily dose of Atabrine, which had the disquieting side effect of yellowing the eyeballs and inducing a yellow cast to the men’s skin.

The squadron medical staff kept a weather eye on another disease indigenous to North Africa: typhus, typically transmitted by lice, and thankfully not prevalent within the air force units. More troublesome was venereal disease, which was seemingly impossible to avoid, particularly after the squadrons were based for longer periods of time at bases situated near population centers.

Captain Blount would eventually serve under several group and squadron commanders, one of whom he was reportedly forced to “ground” because of a diagnosis of incipient polio. His diagnosis was later confirmed, though it did not lessen the withering dressing-down he would have received from the then still-robust commander.

Captain Blount, along with the squadron commander and the operations officer, had to be alert to signs of battle fatigue in the pilots. Blount recognized that the pilots’ lives consisted of one type of stress being superimposed on another, and then on still another.

The business of flying ultra-higher-performance aircraft, laden with high-octane fuel and a half-ton of explosives, was inherently dangerous, even during routine training operations. Added to this was the strangeness that characterized North Africa at that time and the frequent change of locations to other more alien airfields. Worries about parents back home, new wives or newer children. Food was often poor, and rejuvenating sleep rare. Dysentery was common, and all pilots experienced significant weight loss. Physical fatigue increased with each passing day.

He also knew that the extent to which combat fatigue became debilitating could be influenced to a degree by the quality of squadron and group leadership, by the morale of the group, and by preventive or adaptive measures he could deliver.

Anxiety was a constant among the pilots, and naturally the fear of being injured or killed was the primary source of stress, a factor that became dangerously cumulative. Death became a more likely outcome with each mission: more flying resulted in greater exposure which led to increased risk of injury or death, until the point was reached where “possibility” becomes “probability.” Added to this was the double load of grief and anxiety that resulted from losing a close friend in combat. And ultimately, all pilots came to the realization that future dangerous missions were limitless, necessary, and inescapable. In time, the combined effect could cause a pilot to question his motivation to remain in combat.

And the pilots were not immune to an understanding of consequence. Pilots helmed war machinery of great destructive capacity, and each knew that they were responsible for many deaths, including those of innocents. For some, the successful completion of a devastating mission brought great satisfaction in a job well done, a small step in ending the war. For others the uncomfortable recollection of a damaging dive-bomb attack or strafing run could be persistent.

Every pilot felt the stress, and the common refrain “Are you nervous in the service” became ubiquitous because of its underlying truth. Each man had his limit of tolerance to the physical and emotional stresses of combat. The fortunate pilot reached the end of his fifty-mission tour before reaching the end of his ability to withstand the stress. Other pilots—brave, adept, forthright—were not so lucky and began to show signs that they had reached a point beyond their capacity to cope.

Captain Blount was aware of the range of telltale signs of battle fatigue. Some symptoms were of a tactical nature: early returns from missions due to airplane problems that could not be verified on the ground, or being slow to engage the enemy in the air. Others became evident over time: transient fears that became entrenched as permanent anxiety, loss of appetite and unusual weight loss, heavy drinking, frequent sick calls where no illness could be found, depression, seclusion, forgetfulness, preoccupation, and increased irritability were among the most common manifestations of combat fatigue.

These signs could appear in any of the pilots to varying degrees, and it was the flight surgeon’s job to assess the level of stress in each pilot and to both monitor their adaptation to the stress and assist them in their adaptations. As with the pilots, Blount’s job was not without its own stress—it was his task to “keep them flying,” and to insure that the tactical needs of the squadron were met. Sometimes this meant keeping a pilot on flight status despite their evident symptoms.10

And it was also true that some pilots were just not cut out for combat. In the month of May, despite its desperate shortage of pilots, the 14th Fighter Group transferred two new pilots—one after his first mission, and one after his second. There was little point in keeping a man in combat if he was ill-suited: he would create a more dangerous situation for all his fellow pilots.

Future Nobel laureate John Steinbeck, serving as a correspondent during the war, filed a report from London during the early days of the Allied invasion of Sicily: “The men suffer from strain. It has been so long applied that they are probably not even conscious of it. It isn’t fear, but it is something you can feel, a bubble that grows bigger and bigger in your mid-section. It puffs up against your lungs so that your breathing becomes short. Sitting around is bad.”11

Squadron flight surgeon Capt. Lester L. Blount administering to patients.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The five-man Intelligence Unit was under the direction of Capt. Howard Wilson, and included Asst. Intelligence Officer Lt. Royal Gilkey, a staff sergeant and a corporal who served as clerk—all as part of the Air Echelon. An additional sergeant was assigned to the Ground Echelon.

As Intelligence Officer for the squadron, Captain Wilson was responsible for making sure that “. . . the command is not surprised in any theater of operation.” He participated in all mission briefings and provided specific combat intelligence for commanders and pilots. Beyond that, Captain Wilson also served as the counterintelligence officer and was responsible for camouflage and other passive protection measures. He was also responsible for communications security, censorship, and public relations.

Captain Wilson was tough on the men who worked for him because the information delivered through his office could determine the success of each combat mission and whether the squadron pilots would return or not return. When Lieutenant Gilkey first reported for duty, Captain Wilson told him “You make one slip, lieutenant, and I’ll have your ass.”—a message that would be hard to misinterpret.

The Intelligence Unit also delivered intelligence training to the pilots to assist them in making aerial assessments, and then debriefed returning pilots after each mission. This information might include the location and type of flak units, military facilities, enemy aircraft types and numbers, troop concentrations and movements, enemy naval activities and assets, and all too often pilot’s accounts of squadron losses during combat missions. The data was prepared by the Intelligence Unit and forwarded to the Group Intelligence Office for furtherance.

Intelligence material was also incorporated into the squadron’s Weekly Status and Operations Report (WSOR) that was prepared and submitted to the 12th AF Headquarters by Captain Trollope each week.

The squadron adjutant was senior officer in the Ground Echelon. For the 49th Fighter Squadron, that man was Captain James Ritter of St. Mary’s, Pennsylvania, Captain Ritter had been assigned to the 49th in its early days, and was with the squadron during its costly actions in the North African Campaign, during its rebuilding after having been taken off combat status, and during the Sicilian and Italian campaigns.

Capt. James Ritter, Adjutant, 49th Fighter Squadron.

RITTER FAMILY COLLECTION

The adjutant functions much like the city manager of a small town, exercising authority over a wide range of squadron functions. Each morning Captain Ritter visited the Orderly Room and the flight line to review and take action on any urgent matter. He was responsible for reviewing and routing all incoming communications, and was charged with preparing and submitting all records and reports originating from the squadron headquarters.

The condition of the small tent city at Telergma that housed the Ground Echelon was his responsibilty, and he made daily inspections of the “barracks” area, the mess tent, kitchen, and supply area.

He was involved in any charges of dereliction amoung the enlisted ranks, and would twice-yearly assemble the enlisted personnel for a reading of the Articles of War. And he was the pay officer.

It would have fallen to Lieutenant Ritter to supervise the collection of the personal belongings of any squadron serviceman, officer or enlisted, who was killed or declared missing in action, and to prepare and forward the material to surviving family. Many of the pilots who were killed in combat had been with the squadron since its formation and were close friends of Captain Ritter. Collecting their belongings was a painful but necessary intrusion into their lives, and was surely the toughest part of his job with the squadron.12

The airfield at Telergma, built by the French colonial government prior to the war, was seized by American ground forces during the Tunisian Campaign. By mid-December 1942—six months before Koc and Knep’s arrival—it had been improved to accommodate NASAF’s heavy bombers. Most recently it had been a dual-purpose base, housing both bomber and fighter groups. These units had departed Telergma in March, and the 14th Fighter Group, with its three squadrons of P-38s, took over Telergma during the first week of May 1943.13

Hardly a garden spot, Telergma was a “windy, barren, rocky, cold place with some barren hills to the south.” Fred Wolfe of the 82nd Fighter Group related his first impressions of Telergma when he arrived in January 1943: “It didn’t look like much to us from the air, but it looked like less after we landed. You might think by the name Telergma that there was a town there, but there wasn’t—just a little Arab village with a population of about 100. A more dirty and filthy place you’ll never find anywhere in the world. There wasn’t anything about Telergma that made you think of an air base except maybe the muddy strip of dirt that we landed on. Before the war the French had used it as an outpost for their Foreign Legion.”14

Scorpions were abundant and aggressive. In what became a daily ritual, shoes, bedding, and personal gear in the tents had to be checked and cleared. The squadron learned that Algeria was also home to the full range of desert critters, including the Mediterranean recluse spider, the camel spider, and the Egyptian cobra.

Telergma Airfield.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Soon after they arrived, Kocour and Knepper were delivered this piece of bad news: the squadron had been informed just two days prior that there would be no mail for a month. As the American military forces began the buildup in North Africa preparatory for an invasion into Sicily, every cubic foot of available cargo space was taken with supplies, munitions, fuel, and spare parts. As the squadron diarist recorded at the time: “This fact is important as all here are more concerned with mail than food.” A telling statement, given the squadron’s craving for better food.

The news was tough on the squadron’s married pilots—Keith, Trollope, Bitter, Bland, Boatman, Booth, Hageny and Foster—and especially so for Lieutenant Colonel Keith and Lieutenants Bland and Boatman, whose wives were pregnant when the airman were posted abroad.

And outgoing mail would be limited to “V-mail,” a system that involved writing a short note on a template, which was then photographed and returned home on film. This allowed the army to send up to 1,500 letters on one roll of film. Upon receipt, the film was developed and individual V-mails forwarded to the intended address. It was impersonal and unpopular, but it was all the servicemen had.15

When meeting their new CO and their ops officer, the new pilots would also have been given the squadron call signs—identifiers used when talking to controllers or other aircraft. The 49th call sign was “Hangman”; the 48th’s was “Fried Fish.” Each aircraft bore a two-digit number: aircraft of the 48th squadron were numbered 1 through 30; the 49th, 31 through 60, and the 37th, 61 through 90. This system allowed pilots and ground staff to readily know to which squadron a distant aircraft was assigned.16 In practice, the pilot would open radio communications with, for example, “Hangman 47,” instantly identifying him as being with the 14th Fighter Group, 49th Fighter Squadron, and that he was flying aircraft #47.

Pilots were housed in pyramidal canvas tents. Each tent measured 16 feet square, and stood 11 feet tall. When housing four pilots, each man had exactly 64 square feet to call his own. Drinking water and wash water came from Lyster Bags placed throughout the encampment. The mess was set up cafeteria-style, and slit trenches were dug for sanitary necessities. Officers and enlisted personnel alike were protective of their ration cards. With specific items rationed on a weekly, biweekly, or monthly basis, the ration cards provided minimal and utterly necessary comforts for the men who were enduring such challenging living conditions.

Captain Trollope, the 49th’s new squadron commander, was not overly impressed with the preparedness of the replacement pilots, noting in the Weekly Status and Operations Report for June 20–26 that “Replacement pilots need considerable training in altitude formation and dive-bombing tactics.” The problem of preparedness was apparently systemic, as Trollope’s comments were echoed by his counterpart at the 37th, Maj. Paul Rudder: “Pilots are being sent out for combat without sufficient and adequate training. We have received pilots with only 15 hours in a P-38, no single-engine operation [training], no dive-bombing practice, no high-altitude formation and escort practice.”17

Maj. Ernest Osher, commander of the 95th squadron (82nd FG), thought similarly, writing many years later: “I felt strongly that they needed initial indoctrination flights in a combat environment before being utilized on combat missions. We were not given any opportunity until late in my combat tour [late July, 1943] to fly new personnel on training missions. By utilizing them immediately on combat sorties when they arrived, we jeopardized some of our old hands as well as new pilots, and a considerable number, I feel, who could have been utilized effectively, were lost on initial missions.”18

The commanders’ counterparts in the South Pacific also had problems with replacements. In the same week that Trollope and Rudder were complaining to Wing about their new pilots, Maj. John Mitchell bluntly told the Bureau of Aeronautics: “New people coming out there [Guadalcanal] are miserably trained. They’re afraid of the planes because they’ve heard unfavorable comments about them. When they’ve been kidded along a little, flown the planes and learned how stable they are, how well the pilot is protected, what a lot of damage can be dealt out with them—in other words, once they get in a flight—they’re OK. It doesn’t take very long for the ordinary American kid to catch on.”19

Harold Harper, a pilot from the 49th, concurred: “The 49th received pilots who had never flown a plane larger than an AT-6. We had to check them out in P-38s and give them a few hours’ training before sending into combat!”

Harper’s fellow pilot William Gregory recalls: “I think everyone is unprepared for their first [combat] flight. The first flight is going to be exciting for the new pilot, and you don’t have enough time, really, to train them when you are on the line. You are flying missions every day, or every other day, and you just can’t take that much time [for training]. We always tried to give them one or two rides, but that is probably not enough. They were still not prepared. The only way to get prepared is to get in[to] combat. You have to do your best, and if you survive the first few missions, your chances actually improve. You learn fast in combat. You want to get [a new pilot] through his first mission.”

It was clear that the AAF was pumping out pilots as quickly as they could, but with uneven flight training. It was left to the individual combat units—the squadrons—to bring these new pilots up to a level of proficiency that would allow them to participate in combat operations without undue danger to themselves or their fellow pilots. And so, despite a year of intensive pilot training, it was back to school for the new replacement pilots. Kocour and Knepper may have been vexed by this; after all, they had more than eighty hours in a P-38 during Transition training, and almost three hundred total flight hours. Additionally, they had logged many more hours at Berrechid. But realizing the lethality of the situation they were in, it’s a good bet they applied themselves to squadron training.

Since the pilots would be escorting high-altitude B-17s on the majority of missions, high-altitude formation and escort training was a priority. Dive-bombing had not been part of the replacement pilots’ training, so they loaded practice bombs and made dive-bombing runs on a nearby dry lake. Pilots were given a review of radio frequencies, takeoff and join-up procedures, fuel management, oxygen procedures, guns and gun sights, enemy-fighter tactics, and escape and evasion techniques.

Becoming proficient fliers soon qualified the replacement pilots for combat missions. Once airborne and in position their job was to fight, and engaging the enemy required a few critical last second preparations and a cool head. The instant the flight leader “called the break” to turn into oncoming enemy aircraft, the pilot had to drop external fuel tanks, and set gas switches to “main.” He next increased his RPM and manifold pressure, turned on the gun heater switch and combat switch, and made sure his gun sight light was illuminated. In time, these preparations became rote. But new pilots had reportedly been lost when they failed to take any evasive action when “bounced” by enemy aircraft: one explanation was that they were so busy getting organized in the cockpit that they were shot down before they could take action.20

Beyond this additional tactical training, new pilots also needed operational training. Pilot William Colgan noted: “A new pilot’s arrival in a multi-mission combat unit put him in a very time-compressed learning situation. He had to absorb all details of command/unit operational procedures and tactics and lessons of past combat, and learn the enemy and his weapons, the current situation, and maps and features of the enemy territory he would fly over.” He also had to know the location of the “bomb line” to prevent cases of “friendly fire.”21

This training, and the first few missions for the new replacement pilots, was crucial. In addition to their continued training, as commissioned officers, the new pilots would occasionally be assigned the job of censoring outgoing personal correspondence of the enlisted men. As Robert Vrilakas recalled, “It was a tedious and boring job, and one we didn’t particularly like, since we felt we were put in the undesirable position of snooping into their personal life. Despite continual cautions from security officials, some of the letters would divulge our location or strengths and losses. When that occurred the scissors were applied, leaving gaping holes in the middle of a piece of correspondence. It was necessary, but had to have been disconcerting to the recipient of the letter.”22

They might also be assigned to “slow-fly” an aircraft to break in a new replacement engine. When not flying or reviewing procedures, the pilots relaxed as best they could, writing V-mails, playing cards, or sharing endless conversations about flying, girlfriends, and home.

While getting settled at camp and completing their check rides, Knepper and Kocour would naturally have begun to anticipate their first combat mission, wondering with whom they would fly, on what sort of mission, and with what target. What would it be like to look down at an Italian naval vessel, an aerodrome on Sicily or Sardinia, or a large port complex? What would it be like to crisscross over a flight of fifty or more B-17 bombers, all flying in close formation? How would they react the first time an enemy aircraft put them in their sights?

While confident of their own skills and eager to get on with the work for which they had been trained, it would be understandable if their thoughts also turned, however briefly, to their own safety. Nonetheless, it would also be a fair assumption that after a year of training, they were ready to get after the job ahead, whether or not they were fully prepared.

Targeting the Axis

It can be postulated that by mid-1943 the defeat of the Axis forces, however costly, was inevitable. Allied forces had blunted the Japanese advances in the South Pacific. Guadalcanal had been retaken. The Soviet Union had won substantial victories against the Germans on the Eastern Front, even though the losses had been staggering to both sides. North Africa had been successfully invaded with Operation Torch and cleared of Axis forces in the subsequent Tunisian Campaign. At sea, the Battle of the Atlantic had been won, and the strategic bombing offensive from Great Britain, which would eventually have devastating effects, was beginning to show positive results.

The Axis forces knew that the Allies would use their recent successes in North Africa as a springboard for further advances, but the location of the expected offensives was hotly debated within the Third Reich, the Wehrmacht, and the Luftwaffe. Hitler was sure it would be the Balkans. Many German generals thought it would come at Sardinia, and still others thought that Italy itself would be invaded next. Mussolini thought it would be Sicily, but was given little audience. Field Marshal Kesselring thought Sicily most likely, and it was to him that the responsibility for the defense of Sicily ultimately fell.

Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean, sits between the tip of Tunisia and the Italian mainland—a natural stepping-stone for the Allied armies. A rough triangle in shape, Sicily measures 150 miles in the east-west direction, and is slightly larger than the state of Vermont. The terrain is mountainous, reaching the highest elevations at Mount Etna on the northeast corner of the island. Other than a narrow coastal band, the only extensive level ground is in the eastern and southeastern regions of the island. Because of its relatively small size, Axis aircraft could traverse the entire island in thirty minutes.

Well before the fall of Tripoli, Allied war planners had set their sights on Sicily for the next major offensive push against the Axis. And as part of the war plans that led up to Operation Husky—the invasion of Sicily—a carefully developed air plan had been put in place. NASAF’s strategic plan for the Sicilian Campaign was weighted heavily toward degrading the Axis communication capability, including railroads and ports, and establishing air superiority in the region. As early as January, the 12th Air Force had delivered to NASAF a list of first, second, and third target priorities for Sicily, Sardinia, and southern Italy. The top-ten targets included the port at Palermo, the port and rail facilities at Messina, the port of Cagliari on Sardinia, and seven Axis aerodromes.23

The ports were given highest priority because they would be routes through which German troops and materiel would flow to reinforce defensive forces on Sicily, and from which Germans would most likely stage an eventual retreat from Sicily. The seven aerodromes included among the top-ten priority targets were of vital interest to Axis defenders and included the aerodrome complexes at Trapani, Sciacca, and Castelvetrano, in the western region of Sicily, and the aerodromes at Elmas, Decimomannu, and Villacidro, in the southern region of Sardinia.

A NAAF report issued in mid-May gave specific direction as to the conduct of the war against the Luftwaffe in the Mediterranean. It urged bombing concentrations of fighters on the ground wherever they could be found, dislocating fighter aerodrome installations and facilities, and bombing fighter aircraft and engine factories. It further identified the main GAF control center in Sicily—Sciacca—and subcontrols at Pantelleria, Bo Rizzo, and Catania. All would eventually be targeted repeatedly.24

The AAF was able to obtain astonishingly detailed intelligence from a captured German soldier, Adalbert Steininger, who had the two qualities most valued in a prisoner of war: an encyclopedic knowledge of a topic of vital interest to the Allies and a tendency toward volubility—a keen desire to share what he knew.25 Steininger had been stationed at the GAF aerodrome at Comiso and had visited Catania, Trapani, and Marsala on several occasions. He had “an astonishing memory and powers of observation, and [had] been concerned with much actual construction.” While he had little knowledge of current operational activity, he was well familiar with the location, construction, and purpose of a great many of the buildings and installations. He was able to pinpoint the location of water mains, power-supply systems, flight-control towers, command stations for both Italian and German forces, air-raid shelters, workshops and barracks, mess locations, and repair hangars. He even knew the location of Trapani’s barbershop and shoemaker’s shop.

The increased bombing activity on Sicily would be part of a broad ramping up of bombing activity throughout the Mediterranean Theater. These distributed attacks were designed to maintain enemy uncertainty as to where the next Allied landing would be. Attacks were staged as far as northern Italy by aircraft in the UK, and in Greece by aircraft based in the Middle East.

The 49th Fighter Squadron played its part in the Allied run-up to the Sicily invasion. During the month of May, it had flown eighteen combat missions to precisely the targets that NASAF had identified as critical to the MTO.

|

Mission Summary26 |

||||

|

May 1943 |

||||

|

Date |

Mission Type |

Target |

Target Type |

Target Location |

|

6 |

B-25 escort |

Antishipping |

Naval |

Sealanes off western Sicily |

|

9 |

B-17 escort |

Palermo |

Port |

Sicily |

|

10 |

B-17 escort |

Milo & Bo Rizzo |

Aerodrome |

Sicily |

|

11 |

B-17 escort |

Marsala |

Port |

Sicily |

|

13 |

B-17 escort |

Cagliari |

Port and aerodrome |

Sardinia |

|

14 |

B-25 escort |

Terranova |

Port |

Sardinia |

|

18 |

B-17 escort |

Messina |

Port |

Sicily |

|

19 |

B-17 escort |

Milo |

Aerodrome |

Sicily |

|

21 |

B-17 escort |

Castelvetrano |

Aerodrome |

Sicily |

|

22 |

B-17 escort |

Bo Rizzo |

Aerodrome |

Sicily |

|

24 |

Dive-bomb/strafe |

Alghero |

Port, seaplane base |

Sardinia |

|

24 |

Dive-bomb/strafe |

Arbatax |

Port |

Sardinia |

|

25 |

Dive-bomb/strafe |

Milo |

Aerodrome |

Sicily |

|

25 |

Dive-bomb/strafe |

Porto Scuso |

Port |

Sardinia |

|

26 |

Dive-bomb/strafe |

Golfo Aranci |

Port and RR |

Sardinia |

|

28 |

B-25 escort |

Bo Rizzo |

Aerodrome |

Sicily |

|

30 |

Dive-bomb/strafe |

Chilivani |

RR and power plant |

Sardinia |

|

31 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

Pantelleria |

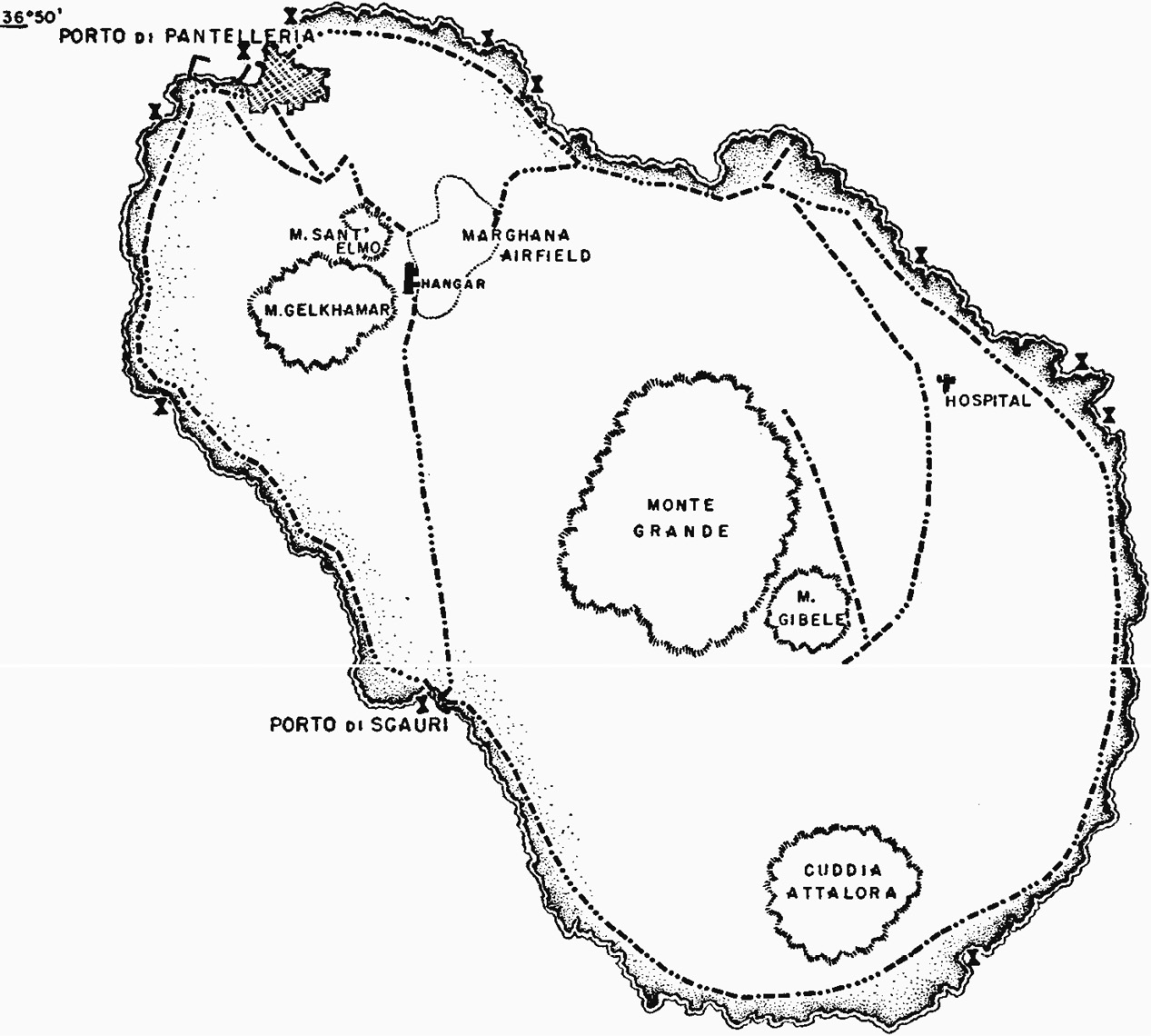

With Sicily decided upon, the next step lay in preparation for the invasion, and an important part of those preparations was the capture of the island of Pantelleria and the lesser nearby islands of Lampedusa, Limone, and Lampione. These islands lay squarely in the path of the invasion, midway between the tip of Tunisia and the southeastern beaches of Sicily. From these islands the Germans operated powerful radio direction finder stations that allowed the German Air Force (GAF) to track the movement of incoming American and British aircraft. At Pantelleria, a small island about 8 miles long and 5 miles wide, fifteen batteries of large guns posed a threat to Allied shipping, and a contingent of roughly eighty single-engine fighters was stationed at Pantelleria’s airfield.27

Great Britain had wanted to occupy Pantelleria since late 1940, but before the Brits could act, the GAF had moved into Sicily, making the risks of assaulting Pantelleria too great. By the spring of 1943, the island appeared as impregnable as Corregidor in the Pacific. In planning for the invasion of Sicily, General Eisenhower had anticipated that the navy would be able to offer eight auxiliary aircraft carriers to provide air cover for the American assault. When in early February of 1942 it was learned that the carriers would not be available, AFHQ began to look hard at other ways to provide the needed air patrols.

Military planners recognized that Pantelleria could provide the bases they needed, and more. Its capture would remove a serious Axis threat to Allied air and naval operations during the Sicilian invasion; it could be used as a navigational aid for Allied aircraft and for bases for air-sea rescue launches, and it would eliminate the enemy radio direction finders and ship-watching stations which would increase the chances for a tactical surprise when the Allies launched their invasion of Sicily.

Eisenhower decided to seize Pantelleria, but without expending heavily in men or materiel. To obviate a full-scale assault, Eisenhower thought of making the operation “a sort of laboratory to determine the effect of concentrated heavy bombing on a defended coastline.” He wished the Allied air forces “to concentrate everything” in blasting the island so that the damage to the garrison, its equipment, and morale, would be “so serious as to make the landing a rather simple affair.” The attack was a further analogy to Corregidor, which had eventually succumbed to intensive Japanese artillery in 1942. Eisenhower wanted “to see whether the air can do the same thing.”28

The island of Pantelleria.

AIR FORCE HISTORICAL RESEARCH AGENCY: W. F. CRAVEN AND J. L. CATE, EDS., THE ARMY AIR FORCES IN WORLD WAR II, VOL. 2

Eisenhower ordered the NAAF into action against Pantelleria, calling for a super-intensive aerial and naval bombardment, “with the idea of so terrorizing and paralyzing its defenders that it could be seized without the use of ground troops.”29

From mid-May until mid-June, the Northwest African Air Forces launched over five thousand sorties against the island. Attacks by Allied medium bombers and fighters—as many as fifty missions per day—quickly neutralized the port. B-17 heavy bombers with fighter escorts began attacks on June 1, focusing on the coastal gun positions. Bomber runs were immediately followed up by antipersonnel and strafing attacks. The sky was saturated with Allied aircraft—so many that planes had to circle the target area until it was their turn to attack.

All squadrons of the 14th Fighter Group flew often in both bomber-escort and dive-bombing missions, sometimes twice daily.

|

Mission Summary—49th Fighter Squadron30 |

|||

|

May 31–June 9, 1943 |

|||

|

Date |

Mission Type |

Target |

Target type |

|

May 31 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

June 1 |

B-25 bomber escort |

Terranova/Sardinia |

Port |

|

2 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

4 |

P-38 bomber escort |

Milo/Sicily |

Aerodrome |

|

5 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

6 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

7 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

8 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

8 |

B-17 bomber escort |

Pantelleria |

Dock and town |

|

9 |

B-17 bomber escort |

Pantelleria |

Dock and town |

|

9 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

10 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

10 |

Dive-bomb |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

11 |

B-26 bomber escort and dive-bombing |

Pantelleria |

Gun positions |

|

11 |

B-26 bomber escort and dive-bombing |

Pantelleria |

White flags seen—no bomb drop |

The Allied assault combined bomber attacks by B-17 Flying Fortresses with offshore naval shelling. American newspapers carried many accounts of the coordinated attack on Pantelleria—code-named “Corkscrew,” and many pilots of the 49th squadron were cited: “Their flak is not accurate, said Lt. Col. Troy Keith of San Jose, Calif., a fighter commander who personally led his twin-tailed fighters in an afternoon smash at the island and came home without meeting a single enemy fighter.” Lt. Mark Hageny added: “It was like watching a battle in a vacuum because the roar of our motors kept us from hearing anything. We couldn’t see what (the Navy warships) were shooting at because the whole end of the island was covered with heavy brown dust clouds raised by the Fortress bombs. You actually could see the earth shake when those bombs hit.” Lt. Robert Riley added: “Everybody practically had his ship over on its back so they could watch the show.”31

Strike photos. Allied combined assault on Pantelleria, May–June 1943.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

On the last mission flown by the 49th against Pantelleria, William Gregory recalls that the pilots were advised during the preflight briefing that if they saw any white flags on the island, they should not drop their bombs. “The weather was bad, but we did see the flags,” he recalled, and the mission returned to base, jettisoning their bombs during the return.32

The British First Infantry Division had prepared for an amphibious assault on June 11, but as the first troops reached shore, enemy resistance ceased. The island was declared secured on June 13—the first strategic position the Allies had captured solely through the use of airpower.

Recognizing the inevitable, the islands of Lampedusa and Limone surrendered on June 13, and Lampione on the 14th. Operation Corkscrew became the first instance showcasing the power of intense air bombardment to induce surrender.33 The action against Pantelleria allowed the 49th Fighter Squadron to gain invaluable experience in the techniques of dive-bombing and bomber escort, experience that would be put to good use in the bombing campaigns to follow.

Knepper and Kocour took no part in the campaign against Pantelleria; they had arrived at the squadron just two days before the island capitulated and hadn’t had enough time to complete their combat flight training with the squadron. They could only watch the P-38s leave and return, and hear the stories of their new squadron mates over mess in the evening. And for the squadron, these eleven days of unimpeded action provided a respite from the heavy bombing escort duties of May and the heavy pilot losses that resulted from those missions.

With the surrender of Pantelleria, the way was clear to begin final preparations for the invasion of Sicily. NASAF again turned their attention to intensified strategic bombing, with Allied forces conducting missions deeper into Axis-held territory over a wide swath that included Sardinia, Sicily, and the Italian mainland. Bombing attacks on German and Italian airfields became particularly intense. After a two-day pause to regroup, rearm, and rest, NASAF conducted a large combined mission on June 15 to the aerodrome complexes in Sicily, targeting the airfields at Trapani/Milo, Bo Rizzo, Castelvetrano, Bocca di Falco, and Sciacca. The intent of these missions was to destroy aircraft on the ground and neutralize the ground assets and landing fields of the German air forces.

The attacks were devastatingly effective. NASAF bombers repeatedly caught large numbers of Axis aircraft on the ground. Hundreds were destroyed by the Allied bombers. NATAF’s tactical bombers were also busy, pounding the airfields on the western and central parts of the island.

Axis airfields on Sicily.

AFHRA

The AAF began reequipping, repairing, and repositioning its bomber and fighter units for the coming invasion. Fighter units were moved farther forward, to bases closer to Sicily. The 49th Fighter Squadron was given notice to expect a move to their next base at El Bathan.

Hopscotching forward was certainly nothing new for the squadrons of the 14th Fighter Group. In the seven months since the group first arrived at Tafaraoui, Algeria in November 1942 in support of Operation Torch, it had already moved six times—roughly once a month. Its tenure at El Bathan was destined to be their shortest—just twenty days.

On July 3 at 0400 the squadron began the move to a newly constructed airfield at El Bathan. The pilots of the squadron were assigned a combat mission, taking off from Telergma at 1140 to escort B-17s to Cagliari and Chilivani. With the mission complete, the pilots landed at their new base. The advanced echelon arrived the next day, and by July 7 the remainder of the squadron had arrived. As a reward for a difficult move, the squadron was taken to Tunis and then Carthage for a swim in the Mediterranean Ocean.34

From that date forward, bombing attacks increasingly focused on Sicilian airfields and Axis communication with Italy, although beach defenses were left alone to preserve surprise as to exactly where the landings were to take place.

About El Bathan

The army had been actively looking for additional forward bases well before the Allies’ defeat of German and Italian forces in North Africa. With each advance by ground forces, tactical bombers and fighters became further removed from the battle line. Air forces planners knew that with the collapse of Axis forces in North Africa, the next battle line would inevitably require overflight of the Mediterranean—further extending the flying time for tactical forces—wherever the next action might occur. Rearward bases resulted in less time-over-target and more difficulty in supporting ground troops. For strategic forces, like the 49th squadron, moving to bases located farther forward meant that more strategic targets could be reached, further degrading the war-making ability of the Axis forces.

In early March a directive was issued by air forces headquarters calling for the establishment of a welter of new air bases for central and eastern Tunisia, including thirteen forward fields for tactical air force units (NATAF) and fifteen fields for strategic units (NASAF) located in the region south and east of Constantine.35 El Bathan was one site in eastern Tunisia under active consideration in May of that year. Unlike other airfields in Tunisia, El Bathan was not a captured German Air Force aerodrome. Rather, it was a “greenfield” location. The clay soil was dusty in dry weather, but muddy in wet weather. A new field destined for short service, its unpaved surface qualified it for “temporary use as a strategic dry-weather base for combat aircraft.”36

The 14th Fighter Group was the first unit to occupy the base and stayed only from July 3, 1943, to July 25, 1943. Upon its departure, the base was used by the 320th Bomber Group (BG) until early November, and was then apparently abandoned.

Construction began on the El Bathan airfield in June by the Air Service Command, one of six concurrent airfield construction projects in the eastern Tunisia region. El Bathan had the most planned runways (three) and the longest runways (at 6,000 feet). It was scheduled for completion on July 5. The airfield was located 3.5 miles south of the village of Tebourba and about 15.5 miles from Tunis, along one of the major paved east-west roads in the region. The field was located just south of this main highway, on the gravel road to Attermine. Following standard army design, El Bathan was constructed to avoid presenting an easy target for enemy aircraft. Aircraft parking spaces (hardstands) were dispersed, as were housing, gasoline, and bomb-storage units, with roads and taxiways connecting the various facilities. Squadrons were sited separately at the base.37

The aircraft hardstands were located around the perimeter of the airstrips. A total of sixty-five hardstands were constructed, each at least 450 feet from the next hardstand, with a minimum of 150 feet from the taxiways, and with aircraft parking sites measuring 100 by 130 feet. The field would occupy a “footprint” of just less than two square miles, and within this site, all three squadrons of P-38 aircraft would operate: the 37th, 48th, and 49th Fighter Squadrons of the 14th Fighter Group—nominally, seventy-five fighter aircraft. Previously at Telergma, the 14th FG had briefly shared the field with the B-26 Marauders of the 17th Bomber Group. El Bathan would be the exclusive base for the P-38s of the 14th Fighter Group.

The bombers would not be far away: The 17th and 319th Bomber Groups were flying B-26 Marauders at this time in Djedeida, just 5 miles to the east; the 320th Bomber Group, also flying B-26s, was operating at Massicault, just 3 miles southeast. With a total of 192 B-26s based in such a small area, on a calm morning, the pilots of the 14th would be able to hear the engines of the B-26s warming up as they received their preflight briefing.38

A small village was located adjacent to the airfield on the west side, and a mosque on the eastern edge of the field. North of the village was an orchard and vineyard. Much of the perimeter was under cultivation in wheat. Army planners seemed to be concerned with local owners of the fields and crops. According to an aerodrome report at the time, “The wheat on this site will be harvested completely by June 25, after which the site would be plowed. A portion of the land is owned by M. Bianco, with residence at Attermine, and the remaining land is owned by the Bishop or Archbishop of Carthage.”39

The army allocated six days for the construction of the airfield. The site included two wells: One 30-foot-deep well was located on a farm on the southern edge of the airfield. Equipped with a small pump, the well yielded clear but salty-tasting water. The second well, located a mile to the east, was also of masonry construction, in excellent condition, and was equipped with a nonfunctioning windmill.40 As an advanced base intended for short-term use, the airfield would include no barracks, hospital buildings, support buildings, hangars, or workshops. There were no special provisions made for ammunition storage, and it was not equipped for night landings.

Leaving Telergma, the men of the fighter group reckoned they had gone from bad to worse. The airfield became known as the “Dust Bowl” by the men stationed there. The hot, dry winds constantly blew airborne dust into the tents, aircraft, and the support facilities.

Moving a twin-engine fighter group, complete with workshops, equipment, supplies, and over 1,000 men was a huge undertaking—one that the group had already performed on several occasions. Men assigned to the Air Echelon had it easy. Forming the advance team, this group flew to the new field in C-47s and readied the new airfield to receive the group’s P-38s that would arrive at the end of the day’s mission. The Ground Echelon was not so lucky—loading everything the group owned in 21 “deuce-and-a-half” (2-1/2 ton) trucks and 4 one-ton trailers.41

Master sergeant Lloyd Guenther, a crew chief with the 48th squadron, recounted his introduction to El Bathan:

It was a long drive [from Telergma to El Bathan], and hotter than Hades in this desert heat. By the time we got to where we were going, everyone had drunk up his canteen of water. The water supply for our new field was a dug well with a stone wall around it and a hand-cranked windless [sic] with a bucket. . . . The well was surrounded by water that missed the trough and was slobbered on the ground by the sheep. A muddy mess, mixed with plenty [of] sheep urine and manure that no doubt was seeping back into the mortared stone wall of the well. MPs stood guard around the well to prevent the thirsty men from drinking the water until it had been chlorinated for 30 minutes.42

Master sergeant Normal Schuller, also of the 48th squadron, recorded:

July 3: We left Telergma 4:00 this morning. Got here at El Bathan about 10:00. Covered a lot of battleground. Never had such a hellish ride—respirator and goggles. Roads torn to hell and a hell of a field here, and hot.

July 4: Never felt such heat. Must be 120 in the shade, and no shade . . . This place will be hell before long.43

The 14th had arrived at El Bathan in that miserable summer of 1943 just in time for the sirocco—a hot wind coming out of the Sahara, blowing at about the same time each day for weeks on end. Fred Wolfe with the 82nd Fighter Group wrote about coping with the strong Sahara winds: “All we could do was dampen a sheet or towel, lie down, and cover ourselves up with it. When the wind was over we’d get up and dust ourselves off.”44

The sun was relentless. Men covered their backs with hydraulic oil as protection against sunburn. Aircraft were too hot to touch, and pilots would be wringing wet before their aircraft got off the ground. Starting their missions with damp clothing, pilots would suffer during high-altitude B-17 escort missions. Climbing as high as 30,000 feet, and losing 3 degrees of temperature for every 1,000 feet of altitude gain, resulted in below-freezing cockpit temperatures. On these missions, the ineffective cockpit heaters of the usually beloved P-38s were in for a round of rough cursing. Lieutenant Gregory reports: “It was just extremely cold, and our hands would get numb. Then when we returned to warmer air, the blood would start to flow again and our hands would just ache. I can remember the excruciating pain when our fingers started to thaw out.”

The sun’s intensity could lead to entirely unexpected consequences, according to Gregory: “Usually when we left in the morning we would have the flaps up on the tents to keep it open. One day, I guess I had been shaving early in the morning. I had this two-sided mirror; it fell on the ground by the side of my cot. During the day when the sun came up, the sun focused the rays on the cot, and it burned up my cot while I was off on the mission. [My tentmates said,] ‘Hey, we had a little fire while you were gone.’ ”

And the heat also caused unexpected problems for the ground crews. “In this heat and humidity we had trouble with the guns freezing up on high-altitude bombing-escort missions . . . Sometimes the planes came home and the guns would be a solid mass of ice and frost from the cold upstairs and the humidity near the ground, condensing on them. We went to a special sperm oil, which kept the guns from freezing.”45

The ground staff’s war required endurance. “They did an extraordinary job under very difficult circumstances, which included having to do all their work outside, in fair weather and foul, because there were no hangars. On the job seven days a week, from early to late, their duties involved a lot of hard, dirty [work]. Unlike the pilots, they were overseas for the duration of the war, and they didn’t have a lot to look forward to in terms of promotions, which were terribly slow for ground crewmen.”46

The 49th would eventually fly twenty-six combat missions from El Bathan before being moved again in late July to a new base at Sainte-Marie du Zit, south of Tunis.

A Look at the Other Sides

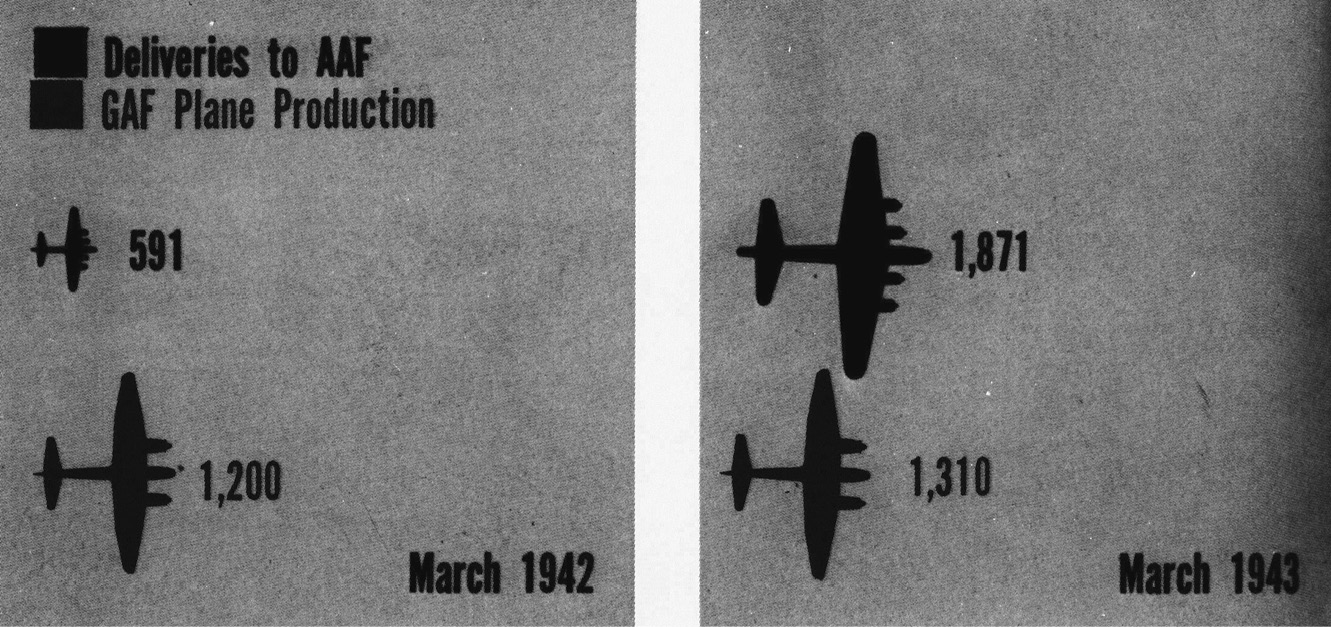

The relative ease with which Pantelleria was taken, and especially noting the almost nonexistent resistance by Italian and German interceptors, prompts the question: What was the status of Axis airpower at this point of the war in the Mediterranean Theater? Historians Samuel W. Mitcham Jr. and Friedrich von Stauffenberg, in their authoritative work, The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory, note: “The Luftwaffe was having more than its share of difficulty in the months preceding the invasion of Sicily. From November 1942 through May 1943 the Luftwaffe had lost more than 2,440 aircraft in the Mediterranean area. This figure represents over 40 percent of the forces on hand in November. During the same period, Allied strength was steadily increasing to a 2.5 to 1 advantage.”47

For the German Air Force in the summer of 1943, three realities had become only too apparent: German industry could not keep up with the increasing demands for aircraft, either in numbers or design. It had not sufficiently ramped up to meet the replacement demands of a war fought on three fronts. And the Me 109 which had so dominated the air over Spain, Poland, and Russia had met its match in Great Britain in the Spitfire, and in North Africa, with the P-38. New, more highly performant German aircraft had been designed, but the manufacturing sector could not stop long enough to retool, and the new designs were late in making their appearance. As Adolf Galland, commandant of the Luftwaffe Fighter Corps, later wrote: “Our fighter production had fallen behind that of the Anglo-Americans in quantity as well as in quality of performance. We needed more powerful engines, longer range, more effective armaments, higher speed, better rate of climb, an adjustment of the ceiling . . . of our planes.”48

Conversely, the American war industry was hitting full stride, outproducing Germany by a factor of two to one. The situation was especially galling for Galland, who wrote: “One of the guiding principles of fighting with an air force is the assembling of weight by numbers, of a numerical concentration at decisive spots. It was impossible to adhere to this principle because of the continuous expansion of the Eastern Front, and because of the urgent demands of the Army.”

Comparative figures on fighter and bomber production of the GAF and AAF, by year.

Impact: the Army Air Forces’ confidential picture history of World War II, Air Force Historical Foundation, 1980

Germany was gradually losing the heart of its fighter corps. By the summer of 1943, German pilots had been flying in combat for four years, and knew they would continue to fly for the duration of the conflict. A prime example is German pilot Hans Joachim Marseille, who over the course of just one year flew in 388 combat sorties and shot down 158 Allied aircraft. Marseille was himself shot down in late September 1942, along with many of his peers who were also lost in combat.

These pilots were simply irreplaceable, given the conditions in Germany at the time. The German pilot training program could not keep up with the demands created by losses in the field. To rush replacement pilots to the field, Germany had made large reductions in the amount of flying time allocated to new students in training—down from seventy-five hours in 1940 to just twenty-five hours in 1943. Any combat veteran from that period would flatly state that pilots with such limited training would be only minimally competent and potentially dangerous for their fellow pilots.

At the same time, American pilots were receiving almost three hundred total hours of flight training, eighty hours of Transition training in the P-38 before leaving the States, and additional combat training hours at bases in North Africa before making their first combat mission.49

The Germans had entered the war with the wrong mix of aircraft. The GAF fought the Battle of Britain with neither an effective strategic bomber, nor a sufficiently long-range fighter. The result was that the GAF lost the Battle of Britain and were not able to conduct an effective strategic-bombing campaign against the Allies in North Africa, particularly after the Allied air forces’ mission had changed to a more aggressive, strategic mode.

Little support could be expected from the GAF headquarters, as Mitcham and von Stauffenberg note:

Goering’s leadership of the Luftwaffe was by now all but nonexistent as he grew increasingly isolated from the top German leadership. He badly misunderstood the Luftwaffe’s situation in Sicily. Rather than recognizing that its problems were due to inferior aircraft, reductions of aircraft deliveries, and inadequate pilot training, he leveled his criticism at the airmen themselves. In a communique to his forces on Sicily, Goering famously wrote: “I can only regard you with contempt. I want an immediate improvement and expect that all pilots will show an improvement in fighting spirit. If . . . not forthcoming, flying personnel from the commander down must expect to be remanded to the ranks and transferred to the Eastern Front to serve on the ground.”50

According to Johannes Steinhoff, the British and American heavy bombardment of Sicilian airfields that began in mid-June had taken a heavy toll on enemy air forces.

The airfields had been ploughed up like arable [land] in autumn. [The Allies had been] laying their bomb carpets everywhere as though intending to destroy the place yard by yard. We were forced to pull out and were having to move our aircraft almost hourly, concealing ourselves in the stubble in between times. Then the whole area started blazing and the flames drove us out. . . . Both the Germans and the Americans learned that the bomb carpet was an extremely effective weapon when used against an airfield, and had a demoralizing effect on airfield personnel. Particularly effective were the smaller bombs that made only shallow bomb craters but released thousands of fragments, projected outwards at high velocity and close to the ground, shredding the outer skins of the German aircraft as though they were made of paper.51

For the German defenders, their archnemesis was the B-17. In later months, an Allied survey learned that a total of 1,100 enemy aircraft had been destroyed on the ground. On the key airfields at Gerbini and Catania were found the wreckages of 189 and 132 aircraft, respectively.

Steinhoff later recounted Galland’s direction: “Up to now we’ve failed in our attacks against the Flying Fortresses [B-17s], the enemy’s most effective weapon by far. The Reich Marshal [Göring] is angry about it, and rightly so. You must all concentrate on one thing and one thing only—shoot down bombers, forget about the fighters. The only thing that counts is the destruction of the bombers and the ten crew that each of them carries.” The Reich Marshal also recognized the impossibility of operating an effective air defense above Sicily, but pressed Steinhoff and others to adopt fresh tactics, create new forms of combat.

Steinhoff shared Galland’s awe over the B-17: “They flew in defensive boxes, a heavy defensive formation, and with all of their heavy .50 caliber machine guns they were dangerous to approach. We finally adopted the head-on attack . . . but only a few experts could do this successfully, and it took nerves of steel. Then you also had the long-range fighter escorts, which made life difficult.”52

Sicily’s air defense was assigned to two Luftwaffe Jagdgeschwader, equivalent to an American fighter wing. JG 77—known as the Herz As Fighter Wing—was nominally assigned to the western region of Sicily, and JG 53—Pik As (“Ace of Spades”)—to the east. Like their American counterparts, each JG was made up of Gruppen (Fighter Groups) and Jagdstaffel (Fighter Squadrons) and was equipped with 120 to 125 fighter aircraft.53

NASAF’s bombing campaign had reduced the normally strong Jagdgeschwaders to a level of minimal efficiency. Area responsibilities were no longer observed, and the commander of air forces on Sicily was forced to shuttle aircraft around Sicily in order to provide some level of protection against the Allied “heavies.”

On July 10, 1943, D-Day for the invasion of Sicily, Allied forces had an inventory of roughly 5,000 first-line aircraft of all types, operated by trained and experienced crews. Even the most generous count of the opposition’s assets credited the Germans and Italians with no more than 1,250 aircraft, few of which were operational. The GAF based in Sicily and Sardinia had suffered such attrition through Allied bombing that it could launch just 128 Me 109 and Fw 190 [Focke-Wulf] fighters.54

It was Steinhoff’s great lament that the nature of air battles had changed. The duel in the air—the classic dogfight—was becoming rare. “Nothing was left of the strange attraction that drew us almost compulsively to aerial combat, first over the English Channel and then in Russia. The chivalry associated with the duel in the air, the readiness to accept challenge again and again, had given way to a sense of vulnerability, and the pleasure we had once taken in fighting a sporting battle against equal odds had long since become a thing of the past. . . . . The strategic bombers, with their frightful capacity of self-defense, came increasingly to dictate the nature of air battles.”55

Steinhoff and others pled their cases to superiors, with no good result. His commander, when confronted by Steinhoff with the reality of the overwhelming Allied airpower, retorted with a croak of laughter: “For heaven’s sake, who in fighters today still bothers about relative strengths? When I tell you that the Allies have about five thousand aircraft against our three hundred and fifty, you’ll be able to calculate the enormous number of chances you have of shooting them down.”

While greatly overmatched, the GAF was far from toothless. The 49th’s frequent opposition in western Sicily, JG 77, was led by German pilots of exceptional experience and ability. Oberstlt. Steinhoff, the JG 77 commander, would be credited with 176 aerial victories, including 6 bomber kills, in nearly 1,000 combat sorties, while being shot down himself 12 times in combat. Steinhoff’s friend Siegfried Freytag was credited with 102 aerial victories, including 2 solo victories over four-engine bombers. And by midsummer 1943, Maximillian Volke already had 35 aerial victories to his credit.56

Steinhoff later wrote: “Admittedly our opponents had succeeded in (smashing our airfields), but we were still flying and still inflicting losses on them, which in turn compelled them to carry out further attacks against our airfields. However the British and the Americans possess such ample resources that they had no need to husband them; they would be unlikely to rest until they had either destroyed us or driven us out.”57