Chapter 7

June 20, 1943

With no missions scheduled for the squadron on the day after what should have been their first combat sortie, Knepper and Kocour had the day to think about the loss of two fellow pilots. Though they had been carefully trained for precisely the type of action that would now face them almost daily, the events of the previous day would have added a starkness to the camp, and a sharpness to their perceptions.

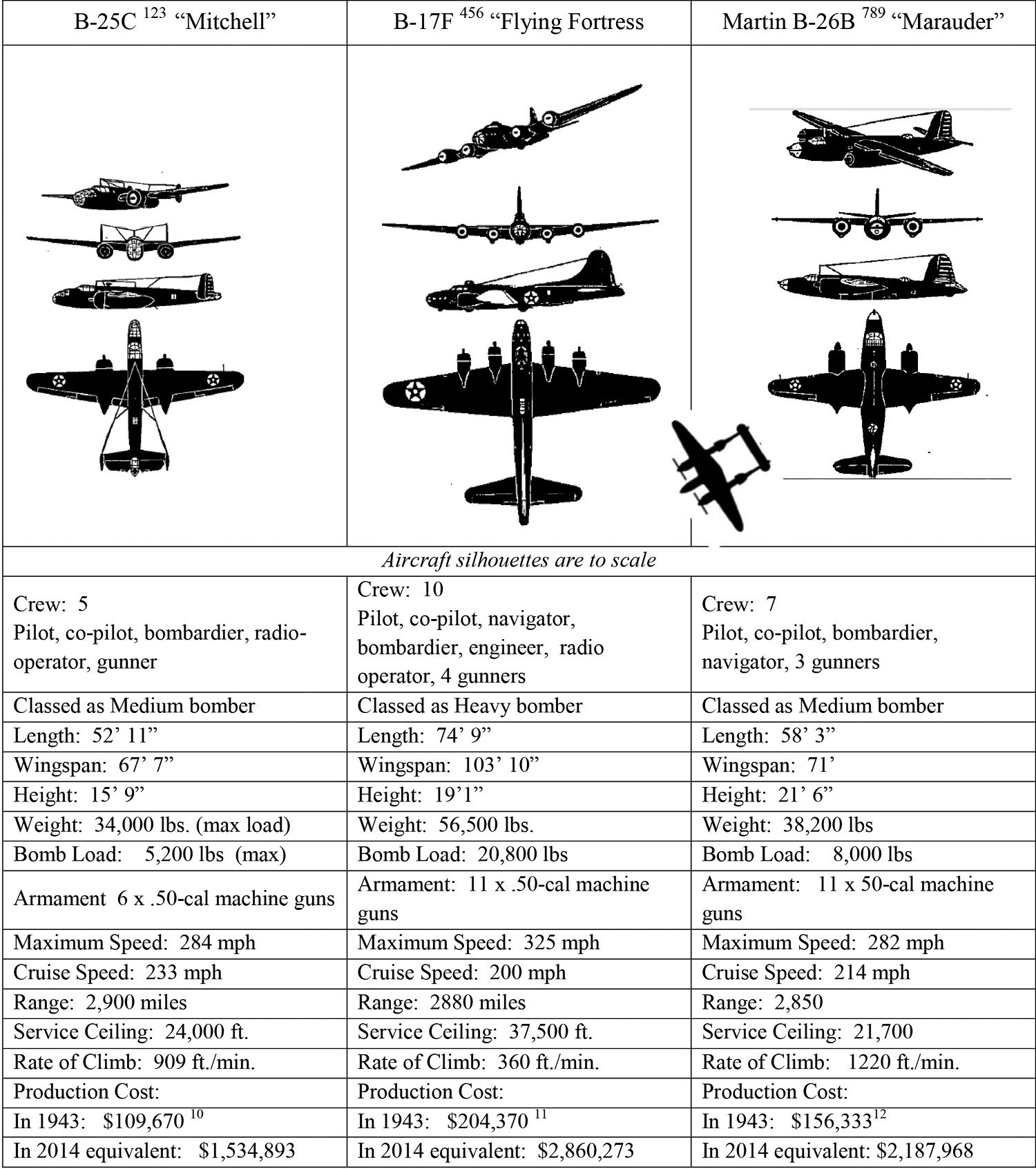

Stopping by the operations tent after evening mess, Knepper and Kocour learned that they were scheduled for the next day’s mission. Details of the mission would come the next morning at the preflight briefing. What they knew was that it would be large mission—all of the squadron’s pilots were assigned—including the newly installed squadron commander, Captain Trollope, and Captain Decker, the operations officer. An all-squadron mission could only mean bomber escort. The new pilots would have reflected on what type of bomber they would be escorting, since the tactics used varied depending on the bomber type.

It would all be new to them; although they had seen many bombers in the air throughout their training, they had had no live practice with any of the three bombers that the squadron would be escorting routinely: the B-25 Mitchell, the B-26 Marauder, and the B-17 Flying Fortress.

B-25

The North American B-25 Mitchell was an American-built, twin-engine medium bomber manufactured by North American Aviation at its plants in Kansas and California. In addition to equipping many American groups, it was flown by Dutch, British, Chinese, Russian, and Australian bomb groups in every theater of World War II. Named in honor of Gen. Billy Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation, nearly ten thousand B-25s were built during the war.

B-25s in formation.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

B-25s in low-level formation flight over North Africa. Note the low-level flight typical of the B-25 in its approach to target.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

High-angle view of B-25s of the 12th AAF.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

North Africa, B-25s in flight.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

B-26

The Martin B-26 Marauder was a World War II twin-engine medium bomber built by the Glenn L. Martin Company in Baltimore. The aircraft received a harsh welcome by pilots, who termed it the “Widowmaker” due to the early model’s high incidence of accidents during takeoffs and landings. It had a number of other colorful nicknames, including “Flying Coffin,” “B-Dash-Crash,” and the “Flying Prostitute,” the latter earned because the aircraft’s short wings provided “no visible means of support.”

Operational safety improved with aircraft design modifications and crew retraining. By the end of the war, over five thousand aircraft had been delivered to the air forces, and the Marauder had achieved the lowest loss rate of any USAAF bomber.

B-26 Marauder on a bombing mission over Rome.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

9th Air Force B-26s over Belgium.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

B-17

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was a four-engine heavy bomber aircraft developed in the 1930s in order to operationalize the army’s philosophy that a daylight precision bomber would be essential for future strategic air warfare. In all theaters of the war, it was a potent, high-altitude, long-range bomber. Bristling with thirteen .50 caliber machine guns, the B-17 could defend itself against fighter attack and was capable of staying aloft even with extensive battle damage. First flown in 1935, production reached nearly thirteen thousand by the war’s end.

Boeing B-17 from the 381st Bomb Group in flight over Europe.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

B-17s under attack during a bomb run over Europe.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

B-17 in attack formation, encountering heavy flak.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Escorting Bombers

As the war continued beyond the Mediterranean, and into 1944 and 1945, strategic bombing missions became of such long duration that escorts—even the long-range P-38s—could not accompany the bombers for the entire mission. Handoffs were arranged, with one formation of escorts taking the bombers partway to the target, another taking over for the escort in the target vicinity, and a third formation to protect the bombers as they returned to their bases.

But in combat operations in the Mediterranean Theater in midsummer 1943, strategic bombing missions planned by AAF headquarters created the perfect match of escort and bombers. P-38s had sufficient range, with extra fuel drop tanks, to accompany bombers for their entire mission throughout the theater.

Bomber-escort tactics were very much influenced by the type of bomber being escorted, and Army Air Corps field manuals attempted to provide some direction regarding fighter escort. In April 1942 the War Department issued FM 1-15, “Tactics and Technique of Air Fighting,” in which the authors primarily addressed fighter tactics for the performance of defensive operations.

In the direct defense of other aviation forces, pursuit provides security by escort. . . . Single-seater pursuit forces . . . normally operate above and to the rear of the defended formation from positions that guard vulnerable sectors and that facilitate immediate counterattack against any enemy force endeavoring to launch a direct attack on the defended formation. Distance from the supported force will be influenced by relative speeds, escort strength, and visibility conditions. Forces in special support counterattack immediately when hostile fighters make direct attacks on the defended formation.13

Although the field manual went to considerable lengths to describe what should be done in a variety of combat situations, it did not say how these tactics should be undertaken. For this reason, much responsibility in refining bomber-escort tactics fell to group and squadron commanders. “The squadrons of the group should be so trained that in the normal methods of air attack the squadrons automatically take proper position to furnish appropriate assault, support, and reserve forces. Radio and visual signals are kept at a minimum. Indoctrination (i.e., pilot training) is the only dependable method of control in the heat of combat.”14

In fairness to the authors of FM 1-15, it should be noted that this important field manual was released in April of 1942, at the very onset of American involvement in World War II. At that time, and during the preceding months when the manual was being researched and written, little direct combat information from the field was available on which to base recommendations for tactics and techniques for the technologically advanced fighters and bombers in its arsenal. The manual contains, therefore, the best theoretical practices for combat tactics as envisioned in mid-1942.

Within six months of the release of FM 1-15, the AAF had received substantial combat experience as a result of operations against the Axis forces from bases in England, and in the course of Operation Torch and the succeeding Tunisian Campaign, and this new experience was reflected in the tactics and formations adopted by bomb and fighter groups.

As seen above, the escort aircraft engaged enemy aircraft only after an assault had been made on the bombers being escorted. This policy did not espouse aggressive initiation of combat by the escorting forces—a policy that would change substantially as the air war moved north.

Dick Catledge, a pilot with the 1st Fighter Group, was unenthusiastic about the defensive posture of the fighter escorts:

[I]t was frustrating to have enemy fighters make a firing pass at us, or the bombers, and then dive away safely, and we couldn’t give chase! The P-38 had four machine guns, and a 20mm cannon, all were in the nose of the gondola, and all fired straight ahead. The enemy fighters were very much afraid to see the nose of a P-38 coming in their direction because of the awesome firepower, and in many cases, this was our salvation. Often, all a P-38 pilot had to do was start a turn toward an incoming fighter, and he would break off the attack.15

Bob Vrilakas, another combat pilot with the 1st Fighter Group, had similar thoughts:

It was often not only nerve-wracking but frustration to see enemy fighters loitering at a safe distance hoping for an opportunity to attack the bombers uncontested. So, while enemy fighters flew at a safe distance and searched for a specific position of our fighter defense that would give them the opportunity to make a quick pass at a bomber without facing our fire, we responded with our own tactical maneuvering. It required our constant weaving over the bombers, with flights crossing in opposite direction to each other. The enemy fighters always had altitude and in-the-sun advantage, which aided them in making a quick pass at high speed and then a return to a safe position at minimum risk. If there was a straggler among the fighters or if we were in a vulnerable position their attack would be directed at one of us.16

Catledge and Vrilakas also felt strongly that keeping the four-ship flight together at all times was unproductive and cumbersome.

Vrilakas wrote: “Both Dick Catledge and I felt that we could more effectively provide bomber protection by breaking the flights into two elements over the target area—a Flight leader and his wingman, and an Element leader and his wingman. This provided much more fighter maneuverability, more effective individual firepower, and more continual coverage of the bombers. The flight of 4 was unwieldy when attacked and in any melee of size ended up in flights of 2 anyway.”

Catledge continued to press his case with the squadron, and even took his argument to the Group Headquarters. That is as far as he got with his tactical suggestions: he was told that the four-ship formation was the way the Army Air Corps had set it up and there wouldn’t’ be any changes.17

During combat in the Spanish Civil War, Luftwaffe tactician Werner Mölders had developed a “finger-four” formation to compensate for cockpit view limitations of fighter aircraft. This formation was based on two mutually supporting pairs of aircraft, with the positions of the number-two and number-four aircraft providing good fields of vision for their four-ship flight. The formation was subsequently adopted by both the RAF and the USAAF, and remains the standard basic flight formation to this day.

.jpg)

Standard configuration for a P-38 combat squadron consisting of 12 aircraft arranged in three “flights,” four aircraft per flight. Each flight consists of two “elements,” and each element consisting of two aircraft. The Flight Commander and Element Leaders were always chosen from the more experienced pilots in the squadron.

Standardization Board, Ontario Army Air Field, SOP, 3 March 1945

The element leaders in fighter formations were the “shooters,” primarily responsible for engaging enemy aircraft. Their wingmen acted as “spotters,” and protected their element leader from rear attack. And despite the cardinal tactical rule for airmen flying in number-two or four position—never to leave their element leader—that rule was sometimes broken, and sometimes for fair reason. The flight leader’s aerobatic maneuvers might be more abrupt than his wingman could follow, or the wingman might be presented with a target he could not ignore.

Replacement pilots were always positioned as wingman on a flight leader. After a few missions, he would transition to the number-four position, and after a few more solid missions, he might be chosen as element leader. Only the most experienced pilots were made flight leader, a position that included promotion to captain’s rank.

With few exceptions, the 14th Fighter Group assigned aircraft from two squadrons on bomber-escort missions, each squadron typically providing twelve aircraft. One squadron would be assigned to lead the escort mission, and one individual within that squadron would serve as overall mission leader. In radio communications, pilots would first identify their squadron by call sign, then their position within the squadron by flight and aircraft number. For example, “Hangman Blue Leader” or “Fried Fish Red 3.”

Unlike the long-range missions that characterized strategic bombing attacks later in the war, the flight time of bombing missions in the Mediterranean Theater permitted the escort fighters to accompany the bombers for the entire mission, with each squadron assigned to a specific defensive zone in the overall formation.

5th Wing Doctrine

The B-17 heavy bombers employed in long-range strategic missions operated within NASAF’s 5th Bomb Wing, which also included three P-38 fighter groups, the 1st, 14th and 82nd, and one group of P-40 fighter aircraft, the 325th, to provide defensive cover for the B-17s against attack by enemy aircraft. Coordinating operations involving vastly different types of aircraft was a priority for the wing, which provided much more specific and certainly more succinct instructions to both the fighter and bomber groups than was offered in FM 1-15.

With regard to P-38 escort procedures, the wing instructed:

In escorting high-altitude bombardment, the P-38 fighters of this Wing have adopted a formation of elements of two airplanes, flights of two elements, and squadrons of three flights each, flying in line abreast. The fighters maintain what might be classed as a medium-close cover flying above the bombers at from 1,500 feet to 3,000 feet. Minimum cruising speed . . . is used, and whenever there is danger of over-running the bombers, a 360-degree in-place turn is made (each flight making its turn in-place, either to right or left as the leader decides).

About ten minutes from the target area the fighters [increase their speed], necessitating a greater number of in-place turns, making the fighters at all times a moving target and yet keeping them over the bomber formation.

When the target is reached, the fighters [increase speed further]. As the bombers turn on to their bombing run, the fighters assume an up-sun position (keeping the sun behind their aircraft and making it more difficult to be seen by attacking enemy aircraft), [retaining this position] as the bombers emerge from the flak area, and are alert for any stragglers which may have been crippled by flak, whom they will proceed to defend against enemy fighter attack.18

Field manuals aside, the main combat tactics used by fighters of both sides were the same: Keep airspeed high by attacking from a higher altitude, dive out of the sun to prevent detection by enemy aircraft, move into a position behind the target, fire, then split away in a diving roll to escape other enemy aircraft that might be trailing.

B-17 bombers in formation, with P-38 escorts flying cover.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

When escorting bombers, “bogeys” (unidentified aircraft, presumably hostile) were called in by the “clock” system and relative altitude using the bomber formation as the point of reference. For instance: “This is Hangman Red Leader. Bogeys at one o’clock high.” The first sentence identifies the escort squadron (“Hangman” was the 49th squadron call sign) and element (Red Flight). The second sentence advises that the bogeys are at one o’clock from the bomber formation and at a higher altitude.

Even with throttles retarded, fighter aircraft operated at higher speeds than most of the bombers they escorted. In order to maintain combat airspeeds while keeping in contact with the bombers, it was often necessary for the escorting fighters to orbit or weave over and around the bombers. And spotting incoming aircraft early, before an attack was launched, was critically important. Since early in flight training, pilots were admonished to “keep your heads out of the cockpit” and to constantly scan the air for bogeys.

Harold Harper relates: “I am convinced that most guys who got shot down never saw the airplane that shot them down. They did not look around. We always used a silk scarf. That was from World War I, but we had silk scarfs because if we wore shirts and looked around, you’d wear your skin off. I still have my silk scarf.”19

Fellow 48th squadron pilot Maurice Nickle related: “My first mission was a high-level escort mission. I believe there were thirty-two P-38s escorting about forty-eight B-17s into Austria. It was quite a sight to see; the P-38s were scissoring back and forth over and above the B-17s. . . . As they entered their approach to the target area there was a solid alley of black puffs of antiaircraft explosions. The P-38s stayed outside of this “alley,” and then we came back over the B-17s that came through after the bombing run. Several blew up in the alley and several were damaged. The main body of P-38s escorted the main body of B-17s that went through intact and still in formation. Then some of the P-38s in two’s or four’s were separated off to escort damaged B-17s back to Italy.”20

The optimum tactical formation for bombers was developed by Gen. Curtis LeMay: a staggered three-element combat box formation, with eighteen bombers in the “box.” This arrangement was compact, but still maneuverable, and was based on a three-aircraft element. In the early months of the war, each flight carried a bombsight in the lead ship, and all planes made their bomb drop when the leader dropped. Later, as bombers began to concentrate on pinpoint targets, a bombsight was carried in every element, and three aircraft dropped off one bombsight.21

Types of Cover

There were several types of escort cover for a formation of bombers, including close cover, medium cover, top cover, area cover, and roving cover. Not all types of cover were included on each mission. The type of cover, and the number of fighters required, depended on the number of bombers, the type of bombers, the target, and the anticipated enemy interception. The fighter’s mandate was to remain with the bombers and to conserve fuel. Unnecessary maneuvering and excessive fuel consumption during the approach to the target were to be avoided, because the first action taken by fighters in responding to enemy aircraft was to jettison external fuel tanks. While the fighter’s performance increased without these tanks, their range was decreased, making it less likely that they would be able to complete the escort mission and possibly jeopardizing their ability to reach base before exhausting their fuel supply.

Dropped tanks also sent a clear signal to the bombers being escorted. Bomber pilot Robert Davila records: “What frightened me every time so that the hair stood [on end] was if our fighter escort suddenly threw off [their tanks]. . . . I then knew that German fighters were nearby.”22

Close cover for heavy bombers usually meant that one squadron was assigned to each of the flanks, one squadron ahead, and one squadron astern.23 Top cover fighters flew 4,000 to 8,000 feet above the bomber force, weaving as necessary to maintain position over the bombers and escorting close cover, and 10 miles into the sun in anticipation of the normal fighter strategy of diving out of the sun’s glare. Maj. Thomas McGuire, writing in 1944, provides extensive details on flying cover:

German aircraft did not always have sufficient numbers to attempt a real interception—breaking the bomber formation. Most often the GAF would make attacks on the bomber formation singly or in pairs, from altitude. In a typical attack, an enemy aircraft at altitude would do a half-roll and make an overhead pass, diving through the bomber formation, clearing away to the side, and then returning to altitude. The only possible counter-tactic is to break up the P-38 top cover into flights and drive off the attacks as they are begun; there can be no general movement of the squadron, for the scattered distribution of the enemy fighters and the impossibility of anticipation leave no alternative but to check each pass as soon as possible after the enemy pilot has committed himself.

The above also holds true to some extent for the close cover. While a number of the enemy will attack from above, there will be others attacking from beneath, particularly against B-24s. At such times the close cover will move down somewhat and will break up into flights to ward off the single passes.

A favorite target for enemy fighters is the “target of opportunity.” Leaving the target area, damaged bombers or escorting fighters may begin to struggle and lag. A crippled aircraft is no match for five or six eager E/A [enemy aircraft], and the best way to forestall such attacks is for the squadron leader to assign flights to each of the stragglers within range of his cover.

B-17s versus B-25/B-26 Escort Missions

The B-17 could carry a tremendous bomb load—up to 8,000 pounds. But it had a low cruising speed—just 160 mph in level flight, and 130 to 140 mph while climbing with a full bomb load. And its rate of climb was the slowest of all the strategic bombers—just 360 feet per minute. This meant that a climb to its normal bombing altitude, 24,000 feet, would require just over an hour. In practice, this meant that the bombers were in climb mode almost the entire flight in to the target, which also required the fighter escort to stay with them. This long, slow climb rendered the bomber formation and its escort more visible to enemy radar sightings, more obvious for enemy fighter sweeps, and extended the time when the formation was within range of the flak batteries that would be overflown during the mission.

Lt. Harold Harper did not like B-17 escort missions. “Slow. You had to weave. You pick them up right off their base, after they had formed up. You’d pick them up and climb all the way to the IP [initial point], up to 24,000, 24,500 feet. Slow—140 mph. And the same way coming back.” Harper was much happier with B-25 and B-26 escort missions. “They would take off and fly on the deck, till they got to their IP, and then they would pour the coal to them, and you had to pour the coal to yours to keep up with them, they’d get up to 12,000 and drop their bombs and down they’d go again.”24 Harper’s preference for escorting B-25s and B-26s was shared by his fellow pilot, Lt. William Gregory: “The B-17s would do a slow climb all the way to the target. They were trying to get altitude all the way.”25

From the Perspective of the Bomber Pilots

Much has been written about the gratitude bomber crews felt toward their fighter escorts. Excerpts from the history of the 321st Bombardment Group—a group often escorted by fighters of the 14th Fighter Group—are illustrative:

It might be [helpful] to note here the feeling we have for the peashooters [fighters], and the boys who fly them. We lean slightly toward the P-38s. On a mission we seldom see them in the vicinity of the target. They are off in parts unknown, raising hell. And although we seldom see our fighters, we also rarely see any enemy planes. The boys tie into them before they get to us . . . so they do their job well and we can’t complain. On a recent raid I saw two P-38s in the immediate vicinity of the target. They were hot after an Me 109 that had come in a little too close to us. He never got quite close enough. They got him. And some of my crew saw him crash and blow up.

Bradley, the boy who hit the water off the coast of Sicily on the same raid, is now back here. It seems that a couple of P-38 boys stayed with him, circling over him until help came from Malta. It’s boys who do things like that who, I believe, deserve the DFC [Distinguished Flying Cross].26

Changing Tactics

The tactics employed by the Allied air forces in escorting bombers were initially much different than those espoused by their German counterparts. As expressed previously by General Galland, commandant of the Luftwaffe, the GAF’s preferred method of defense was a strong offense. Keeping fighters tied to the bomber formation was anathema to the German way of operations. Naturally, the ability to adopt this philosophy is greatly determined by the extent to which an air force enjoys air superiority. While conditions may have permitted this approach for the German Air Force in Spain and in the earlier days of their combat in North Africa, the attrition caused by superior numbers of Allied fighters forced the Luftwaffe to adopt other tactics by mid-1943.

By the time the invasion of Italy was well under way, and General Doolittle had been put in charge of the 8th Air Force Fighter Command in England, the Allied air force supremacy had become a tidal wave. Galland felt that the Allied advantage in aircraft approached two hundred to one. This overwhelming numerical advantage, coupled with the newer, more performant P-38 and P-51 aircraft, permitted a change in bomber-escort tactics in the European Theater of Operations.

During the North African Campaign, the door to General Doolittle’s office held a sign asserting “The mission of the fighters is to protect the bombers.” As the Air Force approached air supremacy, the sign was changed to “The mission of the fighters is to destroy the Luftwaffe.”27

In the words of a fighter pilot:

But we all know what to do: attack on sight, per Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle’s welcome directive when he took over the Eighth Air Force Fighter Command. Before that, fighters had been required to stay with the bombers they were escorting until they were attacked, which gave the Luftwaffe the initiative. Now we were more effective. Our number of victories had increased and, more important, fewer bombers were lost. Nobody is worried about enemy fighters, just the anti-aircraft batteries. I want—all fighter pilots want—to engage enemy fighters.28

Mission to Bo Rizzo

On the morning of June 20, the sun had just crested the low foothills 4 miles to the east when the squadron clerk woke the men at 0500. After a quick and uninspiring breakfast, the squadron pilots began to form up at the Operations tent for the morning briefing, sharing a bit of quiet conversation while waiting for the administrative team to begin the briefing. It looked to be a good day to fly.

The briefing got started with Group Intelligence Officer Howard Wilson referring to a large easel-mounted photograph. Bo Rizzo, also referred to as “Chinisia” by the local Sicilians, was easily identified by all the pilots who had flown missions to it previously, but it was all new for the recent replacement pilots, Knepper and Kocour included. Captain Wilson advised that the 49th Fighter Squadron would be escorting a formation of twenty-three B-26s from the 320th Bomb Group. He confirmed that the B-26s would be taking off from their base at Montesquieu Airfield, 125 miles to the southwest, beginning at 0652. The 49th’s P-38s would be wheels-up from their base at Telergma at 0635, and would rendezvous with the bomber formation at Montesquieu at 0720. The combined formation would then fly on an east-northeast heading for the 270-mile flight to the Sicilian coast, with the P-38s providing top cover. Captain Wilson concluded with an assessment of fighter opposition that the escorting P-38s should expect on the mission and what type and intensity of flak was likely.

The pilots listened nonchalantly, but each was thinking about the mission—fuel supply versus target distance. Estimated time in the air. Who’s on my wing, target flak. And the one constant—enemy aircraft.

Typical Telergma briefing for the 14th Fighter Group at the Operations tent. Maj. Bernard Muldoon of the 48th Fighter Squadron is leading the mission pilots in synchronizing their watches. Aircraft #10, rear, is from the 48th squadron. The mission being briefed in this photograph was to Pantelleria in early June 1943.

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

Following the intelligence briefing, Captain Decker, operations officer, went over all the tactical issues involved in the mission, including how high the top cover would operate, timing points, and compass headings. Meteorology was next, and the briefing officer advised that the conditions were expected to be “CAVU”—ceilings and visibility unlimited.

The mission leader, Lieutenant Leikness, would confirm engine start time, flight positions, and call numbers. Last thing: watch sync. “Check your watches. It is exactly 5 . . . and . . . 45 . . . now! Good luck.” New pilots were sometimes surprised at the informality of the briefings. At this point in the war, there was no “squadron office”; briefings were stand-up and brief—quite different from the more formal briefings the folks at home were seeing on film.

With the briefing concluded, the pilots returned to the supply tent to pick up their mission gear: pistol, life jacket, helmet, oxygen mask, and parachute. Lieutenant Gregory carried a canteen of water, and on two occasions dropped the canteen to bomber crews who had ditched in the Mediterranean.

In later months, pilots would be issued a survival vest that included emergency rations, flares, a first-aid kit, and other equipment, but in the summer of ’43, pilots were pretty much on their own if they were downed. Each carried a .45 and had been given a silk escape map and a small gold coin that might help them barter their freedom from the locals if they were shot down over enemy-held territory. (Harper’s and Gregory’s coins had already been stolen—Gregory’s while he was in the shower.)

Forty pounds heavier, the pilots now made their way to the waiting jeeps for the short trip to the flight line. This combined bomber/fighter mission was carefully timed to coincide with two similar missions being done concurrently by the 319th and the 17th Bomb Groups—all B-26 missions, and all targeting airfields in the northwest sector of Sicily.29 The 319th, under escort by P-38s from the 37th and 48th Fighter Squadrons, would take off at 0700 from their base at Sedrata to bomb the aerodrome at Trapani/Milo, just 10 miles north of Bo Rizzo. The 17th Bomb Group, also based at Sedrata, would send thirty-six B-26s under the escort of fifty P-38s from the 1st Fighter Group on a bombing mission to the Castelvetrano aerodrome, 20 miles to the south. In all, there would be 82 medium and heavy bombers in the stream, with 101 fighter escorts.

Despite the large combined formation, the mission was minuscule compared to raids being conducted by the 8th Air Force in northern Europe as part of the Combined Bomber Offensive. A few days earlier, Cologne, Germany, was targeted by more than 1,000 bombers. The next night, Essen was hit with a similar force. A few days after this day’s mission, Bremen would be hit by 960 bombers. The scope and tonnage of these missions was astonishing and reflects the huge number of strategic targets in Germany for the Allied bomber forces.

Since all pilots from the 49th squadron were included in the mission, it would be organized as two separate squadrons of twelve aircraft each. Five of the pilots assigned to this mission were brand-new replacements: Kocour, Knepper, Cobb, Hyland, and Ogle. And three—Cobb, Hyland, and Ogle—had only reported to the squadron the day before.

Knepper flew in the first squadron of twelve aircraft, flying number-two position to Trollope in the Red flight. Kocour flew in the second squadron of twelve planes, flying number-two position to Bland in the White flight. Reaching his airplane and seeing the crew chief readying the aircraft for the mission, Knepper slid into the cockpit and began the preflight routine that was becoming more familiar to him. Only slightly less anxious than two days prior when his mission was aborted, Knepper again had the same thought: “Please, let everything go right today.”

Takeoff and rendezvous with the bombers went to plan, and the combined formation of forty-seven aircraft set a heading for the Sicilian coast. En route, three bombers developed problems and returned to base. Lieutenant Homer’s P-38 developed a mechanical problem, and his place in the mission was taken by Lieutenant Hyland. Homer, along with Lt. Ogle, a spare not required for the mission, returned to base.

The bombers escorted by the 49th Fighter Squadron “jumped up” to their bombing altitude of 16,000 feet as they approached the target. The bombers made their drop at 0855—22 tons of fragmentation bombs, designed to destroy or damage any aircraft or equipment on the ground at the Bo Rizzo aerodrome. The bombs landed on the north end and on the dispersal area on the west side of the aerodrome, destroying eleven enemy aircraft parked in protective revetments.

The Axis threw up “barrage-type” flak—medium in caliber, but intense. It created a flak envelope, 2,000 to 3,000 feet in depth, centered right on the bombers’ altitude. Yet despite the intensity of the flak, none of the B-26s were hit.

Ten miles to the north, and at exactly the same time, the 319th Bomb Group with its escort of P-38s from the 37th and 48th Fighter Squadrons also made its attack. That mission also reported moderate to intense flak; twelve bombers were hit by flak, and one crewman was killed. Two of the escorting P-38s were also hit by flak but were able to return to base. Enemy aircraft also jumped the bomber formation, both on the approach and while over the target. The P-38s fought them off, with no losses.

Twenty miles to the south, the 17th Bomb Group with P-38 escorts met very determined resistance, both on the approach to the target and after withdrawing, with the German interceptors seeming to be eager for combat. Twelve German fighters jumped the formation before it even reached the Sicilian coast, and another fifteen attacked shortly after the bombers had completed their drop. In the swirling dogfights that ensued in both of these encounters, three American P-38 pilots went missing, and nine GAF Me 109s were shot down.

The B-26s veered left after the bomb drop and headed for the coast. As they exited the target area, in the vicinity of Marettimo Island, the formation was jumped by twenty-five German Me 109 and Fw 190 aircraft, attacking out of the sun from altitude, and eager to take on the “Injuns” of the American Air Force.30 The mission report for the 320th noted: “Last plane this formation reports that escort accompanied formation over target above and to the rear, and was seen to be heavily engaged with enemy aircraft as this formation left coast of Sicily.”31

Gregory remembers: “On this day the enemy aircraft seemed fairly eager and came quite a ways out to meet us and managed to make one pass at the bombers, with very little results. We noticed quite a few stooging around as we hit the enemy coast, but no one bothered with them until they got pretty close or started for the bombers. We were not attacked until we started leaving the enemy coast, but at this time a great number started to make simultaneous attacks. Lieutenant Bland saw the first attack coming and started the break, but was unable to call it, as he had no radio.”

Flying on Bland’s right hand, Gregory called the break, and all twelve fighters in his formation broke around to face the German interceptors, and then broke again as the GAF planes pressed their attack.

The German fighters managed to get in very close on one or two of their passes. Captain Decker later reported: “My wingman, Lt. Manlove, and I went after the 109s. (In going after one) I put everything to the firewall and was in a steep climb when the turbo charger blew out on my right engine. I shut down the engine, feathered the prop and expected to return to base on a single engine. It wasn’t long before the coolant light come on for the left engine.” He feathered that prop and prepared to ditch. “On the glide down I rolled down both side windows and released the canopy. Luck was with me for I landed in the trough and touched down so smooth I actually skipped on the water. Just before the nose started digging in, a swell caught my right wing tip and I did a ground loop on the water.” Not having had any training in either ditching or sea survival, and a bit woozy from a blow to the head he received in the ditching, he had a fair degree of difficulty in jettisoning his ‘chute and deploying his inflatable dinghy before his damaged P-38 slipped away beneath him.

Capt. Richard Decker, upon receipt of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

National Archives

The melee above Decker continued, with the P-38s continuing to engage the enemy interceptors and protecting the bomber formation. Pilots Manlove and Evans each shot down an Me 109, and Gregory, Boatman, and Bland each had a probable kill. Kocour, flying as Bland’s wingman, would have been in on the chase to confirm the “probable.”

The bombers continued their escape, with the 49th’s P-38s continuing to fight off the enemy attackers. Decker’s four-plane flight included pilots Richard, Manlove, and Boatman. As Decker’s plane hit the water, these three pilots circled his location, recorded the coordinates, and provided cover against the superior numbers of German aircraft that were still pressing their attack. Finally, thirty minutes after his downing, the cover pilots were running low on fuel and were forced to return to their base in Tunisia. Captain Trollope, with Lieutenant Knepper on his wing, heard of Decker’s loss and attempted to locate him, but was not successful. Gregory reported that the radios were not operating well that day, and the rest of the squadron was unable to give any close support to Captain Decker because they had lost sight of him.

The 49th’s P-38s returned to base at 1050, and four hours later, a new mission formed up to recommence the search. Eight P-38s, piloted by Trollope, Richard, Bland, Manlove, Gregory, Grant, Lovera, and Hoke, took off from Telergma at 1415. The pilots relocated Decker, just to the west of Egadi Island, waving a distress flag. He appeared to be uninjured, and Trollope contacted the air-sea rescue service to request a pickup. But due to the lateness of the hour, the rescue could not be effected.

The next day, June 21, a second rescue mission was launched by the 49th at 0550. Led by Lieutenant Gregory, it included pilots Foster, Leikness, and DeMoss in the first flight, with Lovera, Homer, Neely, and Boatman in the second. Decker was again sighted in his dinghy at 0745, having spent the night in open water. Food and water were tied to a life vest and dropped to Decker. One of the P-38s was sent back to secure aid from the air-sea rescue service, while the remaining seven aircraft maintained patrol over Decker. Fuel again became an issue for the patrol, and planes were relayed back to friendly bases to refuel. A single-engine floatplane, a British “Walrus,” was led back to Decker’s location, landed, and brought Decker aboard. He was taken to the 97th General Hospital in Tunis, in good condition. Decker’s rescuers returned to base at 1510—a ten-and-a-half-hour mission, and the end of a grueling two days.

On his return, Decker took some ribbing from his friends in the squadron. Harper remembers: “Goddammit, Decker, if I’da been with you, I wouldn’t have let you do that. Lieutenant Knott saw Decker get shot down, and this was Decker’s story: We were in this flight, and my turbo blew up. And Knott said, Yeah, that guy who was right on your tail is the one who blew it up.”32

Leaving their aircraft, the pilots returned to their squadron area to drop off their parachutes, revolvers, and life jackets. Debriefings were conducted by the S-2 (squadron Intelligence) officer who made notations and compiled reports. The debriefings were even more casual than the mission briefings. They were not mandatory, and a return pilot with little to add, or one who was naturally reticent, could give them a skip. William Gregory remembers: “We were debriefed by the Intelligence officer. It was sort of an individual thing—the guys that wanted to say a lot sought out the Intelligence officer. I seldom ever did.”33 Doubtless on this day, with as much activity as there had been surrounding the squadron’s operations officer, the debriefing was robust. In fact, Captain Decker had most likely been shot down by one of the “yellow-nosed kids” from the JG 77 based at Trapani.

According to Gregory, “This [the rescue] was quite an achievement, in that a pilot was rescued from right under the nose of the enemy.”34 Lieutenant Boatman and Flight Officer Richard earned the Distinguished Flying Cross as a result of their valor and extraordinary achievement in the mission to Bo Rizzo, and the subsequent rescue of Decker. Col. Troy Keith, commander of the 14th Fighter Group, also recommended Gregory for the Distinguished Flying Cross for this mission, citing:

As the squadron was leaving the target area it was aggressively attacked by over twenty-five Me 109s and Fw 190s. In the violent combat that followed Captain Decker was shot up and an Me 109 was closing in on his crippled P-38. Captain Gregory immediately saw this 109 and broke into the enemy aircraft head-on, closing to a range of 50 yards, and giving him a burst of machine-gun and cannon fire which set the engine on fire and probably destroyed it. By this action, Captain Gregory undoubtedly saved his fellow officer’s life, because Captain Decker was later able to crash-land his plane safely and was rescued by a plane escorted by P-38s, which Captain Gregory was leading. The flying skill, devotion to a crippled comrade, and fighting spirit of Captain Gregory as a combat pilot have reflected great credit to himself and the Armed Forces of the United States.35

The new replacement pilots—Kocour, Knepper, Ogle, Cobb, and Hyland—had run straight into a steep learning curve on their first combat sortie. Within two days, their squadron had lost two pilots and seen their operations officer shot down and subsequently rescued. Apart from what they learned in the air, these new pilots had learned that pilots will not quickly abandon a downed comrade so long as any hope persists. Duty and loyalty—annealed in combat—became inseparable realities for the pilots of the 49th.