Chapter 16

As mentioned previously, the combat pilots of the 49th Fighter Squadron continued their hard duty through the months of July and August, 1943, returning home at the conclusion of their fifty-mission combat tours.

Of the ten surviving members of the mission in which Lieutenants Bland and Knepper were killed, all survived their combat tour in North Africa. The next chapters in their own personal stories are filled with honor, achievement, and, in too many instances, tragedy. Brief biographies of those ten pilots, and of the squadron commander, are included below.

Red Flight

Lt. William “Greg” Gregory

Greg’s fifty-mission combat tour ended as it had begun—escorting bombers. But in the 105 intervening days, he had grown from a novice to an experienced combat pilot and a leader within the squadron. In that time, he had flown every sort of mission possible with the P-38, had made many friends in the squadron, and had quietly endured the losses as they came. In recognition of his service, he had been awarded the Air Medal, a decoration awarded to pilots upon completion of five combat missions in recognition of meritorious achievement in flight. Following each subsequent five combat missions, pilots’ Air Medals were appended with an “oak leaf cluster” in further recognition of combat service. At the time Captain Gregory completed his combat tour in North Africa, he had accumulated a total of eight oak leaf clusters. In addition, he had been recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross.

His combat missions completed, Greg returned to the States and was reassigned as an instructor pilot. Together with his close friend Lloyd DeMoss he also ferried P-38s around the country, and on one of these flights the two passed through Barksdale AFB in Shreveport, Louisiana. It was there that Greg first met Helen, and they were married about a year later. In time, they were blessed with two daughters, Gretchen Dwire Gregory (husband, Gene) and “Cookie” Gregory Ruiz (husband, Phil), and grandchildren J. R., Boo, and Greg.

Greg would eventually fulfill his early teaching ambitions by earning his undergraduate degree in education from Centenary College, and later a master’s degee in international affairs from George Washington University.

Greg remained in the air force briefly following the end of the war, and in 1947 left the active service and remained in the Air Force Reserve. He and his wife moved back to Shreveport, and at nearby Barksdale AFB, Greg continued to fly—without pay—on weekends. Barksdale was a bomber base, and Greg switched from fighters first to the B-29 bomber, and then to the B-47. His reserve duty continued to involve occasional overseas postings, and it was after returning from a three-month assignment to Morocco that he was interviewed for a highly classified assignment with the high-altitude “Black Knight” Program. The interview was held at Turner AFB in Albany, and Greg was introduced to the aircraft that was at the center of the program—the Martin RB-57D Canberra, a specialized high-altitude strategic reconnaissance aircraft.

Black Knight was the U.S. military’s early efforts at developing a capability for overflight and surveillance of the Soviet Union. In brief, the program would use the RB-57 as the basis for a new, more performant aircraft. The new plane would use the fuselage of the RB-57 with longer wings, a honeycombed construction, and a larger engine. The B57-D2 version was used for an interim intelligence program from 1956 to 1960. In a later evolution of the program, the aircraft used would be designated the U-2.

Just twenty of the B57-D2 aircraft were built. As is cited in the literature, “Little is known about their use.”1 Thirteen of the aircraft were equipped with cameras and six with the automatic ELINT system for collecting radar data, and one was equipped with the very first (experimental) infrared system.

Lt. Col. William J. Gregory, commander, 4025th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, 4080th SR Wing (SAC), Laughlin AFB, Del Rio, Texas, 1959.

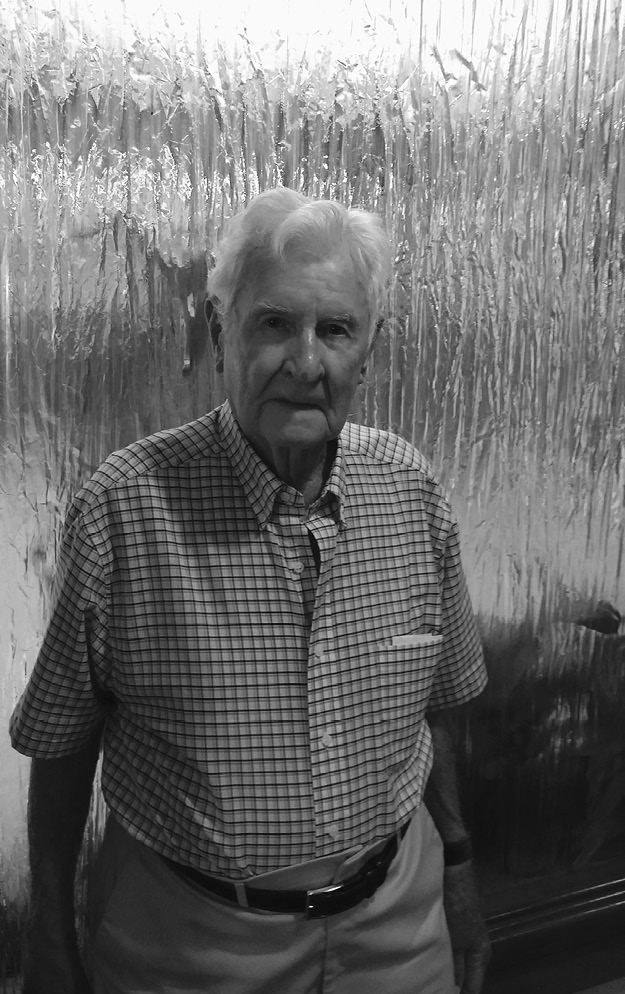

COL. WILLIAM J. GREGORY (RET.)

Black Knight squadron commander Lt. Col. William J. Gregory.

COL. WILLIAM J. GREGORY (RET.)

After four years as commander of this squadron, in April of 1960 Greg was selected for the CIA’s U-2 Program, and was named as operations officer for the U-2 squadron located in Atsugi, Japan. Almost concurrently, Gary Powers’s U-2 was shot down over Russia. With chaos in Washington, Greg’s orders were on hold for three months before he was assigned to Edwards AFB, where he took charge of a squadron of ten U-2 aircraft.

Greg’s unit began to overfly Cuba on intelligence-gathering missions in October of 1960. In early 1961 his group began overflights of Vietnam—four years before the large buildup there.

In late August of 1961, one of Greg’s pilots, Bob Erickson, found the first surface-to-air missiles in Cuba. Identifying the SA-2s was important because they were normally deployed by the Soviet Union in a defensive circle around intercontinental ballistic missiles. Locating twenty of these SAM missiles on the western end of Cuba, it was evident what was coming next from the USSR. At this point, the intelligence missions were turned over to the U.S. Air Force, and on the basis of their confirmatory findings, the United States implemented a blockade leading to what is now known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In 1964 Greg was offered the position of operations officer for the new SR-71 spy plane. The position represented a phenomenal career opportunity for Gregory, but would take him away from his family almost entirely for two years, followed by three more years after that with scant contact. With his daughters in high school, and his wife dreading another long period of separations, Greg declined the position, and instead accepted a placement in the National War College.

After one year at the college—one of the most prestigious assignments in the air force—Greg accepted a position at the Pentagon, working on research and development for reconnaissance systems, including groundbreaking work on the early air force drone systems, and on systems that would later become “smart bombs.” After five years at the Pentagon, Greg accepted a position as vice commandant of the Air Force Institute of Technology. At that time AFIT operated a graduate program at Wright Patterson in aeronautical engineering, and in management, and placed several thousand officers in colleges and universities around the country.

Over the course of his career, Greg piloted fifty-five different airplanes, including naval aircraft. He is one of a select few air force pilots to have attained the Aircraft Carrier Qualification, earned from the decks of the USS Lexington.

In addition to the combat decorations earned in World War II, Greg was awarded the CIA’s Medal of Merit, together with a personal letter of commendation from President John F. Kennedy. For security reasons, the awards were retained at CIA Headquarters until his involvement in the Cuban Missile Crisis was de-classified in 1975.

Greg retired from what can only be described as an awe-inspiring career in the Air Force in 1975, but continued working as assistant director of Workers’ Compensation for the Office of the Attorney General of the state of Texas for an additional 15 years. He and his wife Helen enjoyed fifteen years together after his retirement, before her death in 1990. “She was such a loyal person—she was a great wife,” says Greg. “And she did a really great job with the girls. I am really proud of both my girls.”

With time on his hands, Greg turned to cycling at the age of seventy-five. His passion for cycling grew, and he made extensive cycling tours in France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, and England. He cycles to this day, and is, by any standard that may be applied, a remarkable man.

Lt. Frederick James Bitter

Lt. Frederick James Bitter, known to his squadron mates as “Jim,” was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in recognition of his valiant actions in what would be his final combat mission—a B-17 bomber escort over Orte, Italy in late August 1943. His commendation includes: “On many combat sorties his leadership, gallantry and selfless devotion to duty have reflected great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United Stated (by command of Maj. Gen. James Doolittle).”

Lieutenant Bitter came very close to not surviving this final mission. Operating at 26,000 feet while escorting the B-17s, Bitter’s wingman peeled out of formation when one of his motors failed. With three enemy fighters closing in on the crippled aircraft, Bitter went on the attack and shot down two of the German aircraft. At that point, he came into the sights of two other German fighters. His aircraft was hit with cannon shell, and he was only able to escape by throwing his P-38 into a steep, two-mile spinning descent.

On being interviewed later by his local newspaper, Bitter commented that he did not take much stock in prayers while taking his training in the United States, but after he went into his first battle he had all the faith in the world in a prayer when the going got rough. “At least my prayers were answered on my last mission; it was the only way that I could have gotten out of the mess.”

In addition to the DFC, Lieutenant Bitter earned the Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters during his tour in North Africa.

Mary Jane and Fred Bitter. Photo dated Sept. 19, 1942, just prior to Lieutenant Bitter’s posting abroad.

RICK BITTER

Lieutenant Bitter returned to his wife May Jane following his combat tour, and was reassigned as an instructor in the 443rd Training unit. Together they raised four children: Rick, Greg, Rebecca, and Amy. His son was named after William “Greg” Gregory, Lieutenant Bitter’s close friend and frequent wingman in the Mediterranean Theater.

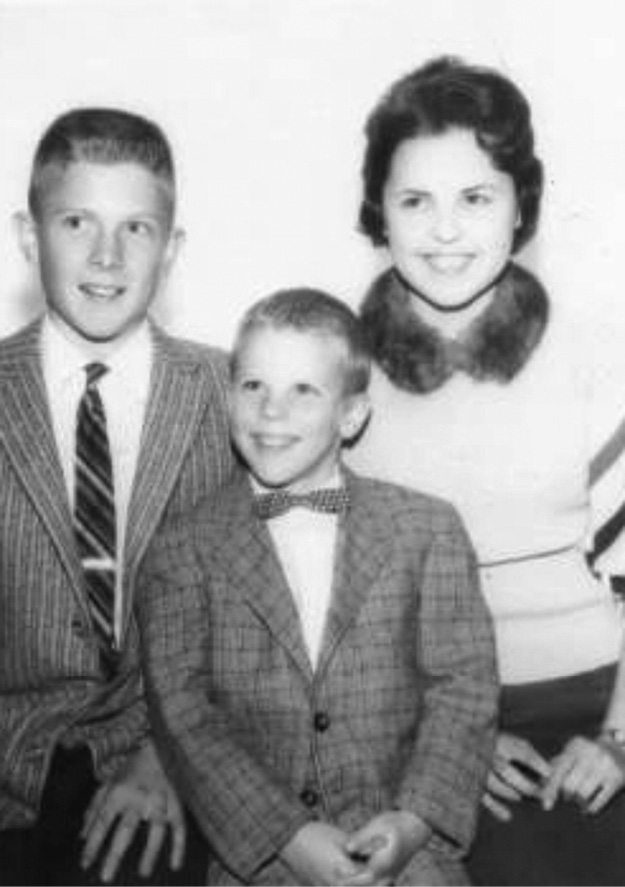

Fred and Mary Jane Bitter with children Rick, Greg, and Rebecca. Daughter Amy still to come.

RICK BITTER

Bitter continued his military career in the U.S. Air Force Reserves, retiring with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Fred Bitter returned to the family business after the war, managing Bitter’s Grocery Store with his brother Herman until 1965. He then worked as supervisor in the railroad and steel yard at Pullman Standard for fifteen years until his retirement in 1979. Not content to be idle, he then worked in the maintenance department at Friedman’s market for five more years.

Fred Bitter died on February 10, 1994 at the age of 77.

Lt. Art Lovera

1st Lt. Art Lovera returned to the United States in mid-September, 1943. He was assigned to the 440th Base Unit as a flight instructor, along with Harold Harper and other returning combat veterans.

Lieutenant Lovera’s life back home was troubled and unsettled. His son, Dusty, recalls:

As a kid coming up, my Dad never really spoke about the war anytime. Never told us anything about it. I never knew if that was right or wrong at the time. We never pushed him on it because he wasn’t one that you could readily sit down and talk about it. He pretty well clammed up.

By 1945 Art’s family consisted of a wife, a stepson, a son. Two months later a third son was born, and at that point Art’s wife deserted the family. He remarried twice more. Of his father’s second wife, Dusty has nothing good to say. But Dusty fondly recalls Art’s third wife, Norma, a kind and generous woman who was good for Art.

Dusty also has this to say: “If you relate it to guys in my time that went to Vietnam, they’ve been fighting it since they got back. A lot of the guys I golf with are Vietnam vets, and our getting together has done more for our vets here than going to any doctor has, to be honest with you. We went through that, and we heckle each other as we play. And after we play we’ll sit down and shoot the breeze for an hour or an hour and a half. But it helps, and I don’t think my Dad had anything like that when he got home. When you look at when our Dad grew up, and what he came through, they had it so much tougher than what we had.”

First Lieutenant Lovera was discharged from the army on January 16, 1946 at the AAF Regional & Convalescent Hospital at Fort George Wright, Spokane, Washington. His service medals included the Air Medal, with eight oak leaf clusters—a testament to the many combat missions he flew from North Africa.

Art Lovera died on January 17, 1982. His Certificate of Service includes the notation: “Wounds Received in Action. . . None”—A categorization that is tragically inaccurate.2

Beryl Boatman with John Harris.

MICHELE BRANCH

Lt. John Harris

Lt. John Harris completed his fifty combat missions with a fighter bombing sweep over Avellino, Italy.

On his return he commented that he “has failed to note any indication that German soldiers are weakening or that they have lost faith in their fuehrer and his blatant promises.”3

He returned to the States in November 1943, and was assigned as flight instructor in Washington and California with the 443rd Base Unit. On May 20, 1944, having just received orders for a second combat assignment overseas, Lieutenant Harris’s aircraft’s engine failed during a routine training flight. He was able to control his plane just long enough to heroically guide it to a local park away from the businesses and residential areas of heavily populated Ontario, California, and was killed in the crash.

Lieutenant Harris had been awarded the Air Medal with ten oak leaf clusters and the Distinguished Flying Cross in recognition of his overseas combat duty.

Lt. Martin Foster

Lieutenant Foster arrived in North Africa in March 1943, having journeyed first to England with the other pilots who would “restart” the 14th Fighter Group. His combat service nearly ended on his fourth mission, on May 21, escorting B-17s on a raid to Castelvetrano aerodrome on Sicily. Joined by twelve aircraft each from the 37th and 48th Fighter Squadrons, the twelve P-38s from the 49th took off from Telergma at 0730. Lieutenant Little was leading the Blue Flight, with Lieutenant Foster as his wingman. The bombers made their drop amidst heavy but inaccurate flak over the target, and the combined bomber-fighter formation encountered and engaged enemy aircraft almost continuously on the return leg. At 1015, Lieutenant Foster and his leader, Lt. Albert Little, were last seen diving on an enemy Me109.

In Lieutenant Foster’s words:

Another pilot (Lt. Little) and I made the beginner’s error of going after what seemed to be a couple of easy ones. It turned out to be a Jerry trap and a couple of ME-109s proceeded to show us their fire power.

Lt. William Gregory, in Blue flight, recalls:

We got into a really big scrap. There were 12 of us, and . . . there must have been 20-30 enemy aircraft and we were back and forth and all of a sudden I was all by myself. I looked down and saw a P-38 with four 109s in a circle. I dove down through them, and made one pass, and got two of them on me. I did not know at the time, but it was Little. I got two of them on me, and one of them followed me all the way to the coast, to North Africa.

In the frantic aerial combat, Lieutenant Foster’s left engine was shot out, and he lost use of his left aileron and left inboard flap. He limped his way back to the African coastline, and crash landed on a beach near Bizerte.

The plan was wrecked, but I wasn’t hurt—not until two hours later. I had landed near a British camp. I went swimming with some English soldiers and then they took me for a ride in a captured Nazi reconnaissance car. We hit a bump and I sprained by wrists.

Lieutenant Little was never recovered.

Lieutenant Foster continued to fly combat missions, and in early September 1943 succeeded Captain Decker as Operations Officer of the 49th Fighter Squadron. His service tour ended with fifty-one combat missions, his last coming on October 11, 1943, also escorting B-17s, on a raid to Sardinia.

On his return to the States in January 1944, and his reunion with his wife Faye, Lieutenant Foster was reassigned as a flight instructor with the 4th Air Force at Santa Maria Army Air Base in California, teaching new flight cadets how to fly the P-38 and P-51 fighters. His squadron mate Harold Harper and his wife occupied the other half of the duplex Martin and Faye lived in while assigned to Santa Maria.

Col. Martin A. Foster.

NATIONAL PERSONEL RECORD CENTER

He remained in the service following the end of the war, and in August 1946 was named executive officer of the 39th Fighter Squadron (35th Fighter Group), and later would become the Group Operations Officer.

He was twice assigned to the Air University at Maxwell Air Force Base, served at air bases in Japan, England, and the United States, and completed one tour at Ton Son Nhut Air Base in Vietnam, serving as assistant deputy chief of staff.

In early 1970 he was named commander of the Niagara Falls Air Base. He retired with the rank of colonel on January 21, 1972, having been awarded the Bronze Star and numerous other campaign and service medals.

Martin and his wife Faye had five children: Marion Lee, Carolyn, Elizabeth, Dennis, and Michael.

Martin Foster died on April 9, 2003 at the age of 84.4

White Flight

Capt. Richard Decker

After completing his combat tour, Richard Decker returned to the United States in late 1943 and was assigned as director of operations and training at Abilene Air Base in Texas.

When the war ended he was assigned to Headquarters XII Tactical Air Command in Bad Kissingen, Germany. He returned to the States in 1947 to serve as squadron commander of the 307th Pursuit Squadron (31st Pursuit Group), based at Turner AFB in Albany, Georgia. In 1949, Colonel Decker was sent overseas for the third time, assigned to the 51st Fighter Wing as deputy for materiel. At the outbreak of the Korean conflict he was sent to Japan as tactical inspector for Far East Air Forces. He returned to the United States in 1951, assigned to the 4706th Interceptor Wing in Chicago, Illinois. In 1953 he was appointed air defense liaison officer to the U.S. Navy’s Eastern Sea Frontier headquarters in New York City.

Colonel Decker was assigned next to Roslyn Air Force Station, Long Island, New York, as inspector general for the 26th Air Division. He left Roslyn in 1957 to attend the Jet All Weather Fighter School at Perrin Air Force Base in Texas, flying F-86 aircraft. Upon completion of the course, he was assigned to postings in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and St. John’s, Newfoundland. He retired from the air force at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver, Colorado, in 1961, a command pilot having been awarded decorations in both World War II and Korea, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Bronze Star, and the Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters.

Richard and Louise split their time between their Colorado ranch near Anton and a home in Naples, Florida. For many years he owned and flew his own plane between Florida and Colorado.

Louise Decker passed away on February 23, 1998. Richard followed fifteen years later, on October 10, 2013.

Flight Officer Charles Richard

F/O Charles Richard returned to the United States after earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters. He began instructing P-38 pilots at Salinas and Santa Maria. After one year, he was again posted overseas, transiting India over the Himalayas, en route to China.

He flew twenty-six missions out of Mengzi, China, into French Indochina. On one mission his plane was hit, knocking out one engine and shattering the gun sight in front of his face, sending shrapnel into his right hand, arm, and leg. For this action he was awarded the Purple Heart.

After the war, he returned to complete his education at McNeese College, and then earned a law degree from Louisiana State University. After graduation, he worked briefly as a corporate credit manager, and began his own law practice. He later joined the district attorney’s office, and worked there for twenty-four years, retiring in 1984.

True to his roots, Charles was an avid hunter of deer, rabbits, ducks, and squirrel. And his culinary skills with wild game were widely praised: deer jerky, smoked ducks, smothered rabbit or squirrel, and his specialty—shrimp and okra gumbo.

Charles married Mary Margaret “Mimi” Stine and they raised three children: Charlane, Charles W. Jr., and Velarie. After Mimi passed, he married Jeanette Burge and became stepfather to her three children.

In a testimony to his service, in 2013 he received the Louisiana Medal of Honor.

Jeanette would later write of him: “I would describe my husband as a man’s man, an honest man, highly intelligent, elegant, and as one who knew and practiced all social graces. He was truly a southern gentleman, but one who could and would stand his ground when necessary!”

Lt. Harold Harper

Lt. Harold Harper flew his last combat mission on August 28, 1943, leading the 14th FG’s three squadrons on a B-17 escort mission to Terni, Italy. This mission was the farthest north that the group had ever flown, and when he returned, he had logged a total of 215 hours of combat flying in his fifty missions.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for action just a few days before his final mission. On August 19, 1943, while escorting B-17s on a mission over Foggia, the formation was hit by enemy fighters. When fifteen of the enemy fighters attacked his formation, Lieutenant Harper saw an Me 109 directly pressing in to attack a crippled P-38. Realizing his fellow pilot was in danger, Harper “unhesitatingly turned his plane directly into the path of the hostile fighter, and by drawing the enemy fire to his own aircraft, enabled his comrade to parachute to safety. He then outfought the Me 109 and shot it down in flames.”5

Capt. Harold Harper.

LT. COL. HAROLD HARPER (RET.)

With several other pilots from the 49th squadron who had also completed their combat tour, Harper transited Rabat, Morocco, en route to England. There they boarded a C-54 transport for the long flight to Iceland, then Presque Island, Maine, and finally to Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio. Lieutenants Harper, Knott, and Homer boarded the “Super Chief” to the West Coast and were treated to a heroes’ welcome on their arrival at Bakersfield, where the local press dubbed them the “Three Musketeers.” The three friends were assigned to the 371st Fighter Squadron (366th FG), first posted to Salinas, California, then to Santa Maria, where they remained for the duration of the war as instructors in P-38 fighter tactics.

Lts. Knott, Harper, and Homer.

Bakersfield Californian, 21 Oct 1943

Harper was especially pleased to complete his combat tour and return to the United States with his fellow flight school students, good friends, tentmates, and squadron pilots, Carroll Knott and Monroe Homer. He was also pleased that their other tentmates, Lieutenants Manlove and Evans, were able to complete their combat tour safely and return to the United States.

Harper was separated from the service in September of 1945, at Salinas, California. He returned to college and graduated from Oregon State University in 1947, with a BS degree in biology, and began a career as a research biologist with the California Department of Fish and Game.

He was called back to active duty when the Korean War erupted, flying P-51s at Tyndall AFB in Florida. He trained as an aviation physiologist at Gunter AFB in Alabama and was then assigned for the duration of the Korean conflict to Mather AFB in California, as commanding officer of the Physiological Training Section.

Harold was discharged from active duty in September 1953, returning to work with the State of California. He remained in the Air Force Reserves until retiring in 1968 with the rank of lieutenant colonel. In 1984 he retired from the California Department of Fish and Game.

Harold Harper, August 15, 2014.

RICHARDSON

Lt. Beryl Boatman

Following his combat tour in North Africa, 1st Lt. Beryl Boatman returned home in the fall of 1943 to be reunited with his wife and to see his five-month old son for the first time. At the age of 21, Boatman was a hardened combat pilot, credited with having shot down two—and possibly as many as five—enemy aircraft, and logging more than 200 hours of aerial combat flying.

After a brief posting stateside, Beryl Boatman served a second combat tour with his old unit—the 49th Fighter Squadron—where he was promoted to squadron commander. Before ending this second tour, he completed 32 more combat missions, with a total of 361 combat hours, a remarkable achievement considering the great dangers associated with flying the P-38 in combat.

Boatman completed his baccalaureate degree in physics at the University of Oklahoma in 1950, and was soon teaching at the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

In July 1952 he was assigned to Air Command and Staff School at Maxwell AFB, administering the Project RAND contract, a program designed by air force general “Hap” Arnold as a way of connecting military planning with research and development decisions.

In August 1953 the world learned that the Soviet Union had detonated a hydrogen bomb, resulting in an emergency program to develop America’s first intercontinental ballistic missile with the primary planning and policy work for the program assigned to the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division, Headquarters Air Research and Development Command.

From 1954 to 1959, Beryl Boatman served with the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division. The resultant missile system, the Atlas ICBM, became operational in 1959. In addition to ICBM development, the research conducted through the ARDC led to scientific and engineering breakthroughs that allowed satellites to be launched into space, a capability spurred on by the launching of the Soviet Union’s Sputnik 1 in October 1957.

Recognizing the immense potential of ballistic rocketry, Boatman’s vision extended well beyond military applications. In 1955 he posed a curious question to his brother Karl, a cardiac surgeon, about the half-life of red blood cells. When asked what prompted the question, Boatman replied: “Because when I get this ballistic missile thing going I want to put a man on Mars and bring him back and I don’t know how long it’s going to take.”

Following his successful contributions to this program, Boatman returned to the University of Oklahoma to complete his master’s degree in nuclear physics in 1959.

From 1959 to 1961 Beryl Boatman was executive officer of the Air Force Systems Command. In 1961, at the age of 39, he was named military assistant to the assistant secretary of defense.

According to his daughter Michelle Branch, “He loved flying—that was his bliss.” By the fall of 1961, realizing that his flying days with the air force were coming to an end, Beryl retired. At the time of his retirement, Beryl Boatman held the rank of colonel in the Regular Air Force and was a command pilot with over 2,000 hours in all types of aircraft.

His decorations included the Distinguished Flying Cross with one oak leaf cluster, the Air Medal with fourteen oak leaf clusters, the Legion of Merit, and many awards and commendations.

After a distinguished career which saw fundamental changes in air force capabilities and doctrines, Beryl Boatman died of natural causes in 1983 at the age of 62.

Beryl Boatman receiving the Legion of Merit from General Schreiber, 1961.

MICHELE BRANCH

Blue Flight

Lt. Herman Kocour

Lt. Herman “Koc” Kocour completed his fifty combat missions with a B-25 escort mission to Grosseto, Italy, on October 22, 1943. His combat hours totaled 218, and he received the Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters. During his time with the squadron, he saw thirteen of his fellow pilots lost in action.

Herman received orders home on October 26, 1943, and almost immediately upon his return married his sweetheart, Agnes Josephine Finn, on Thanksgiving Day, 1943. He was assigned as an aircraft maintenance officer, and separated from the service on March 17, 1946. According to his family, he never flew a plane again.

Herman earned his degree from Wichita State University, putting himself through college working as a butcher. He became an accountant, first with the firm Coffman, Kocour and Taylor, which merged in 1961 with Fox & Co. to become one of the nation’s largest accounting companies at the time. He became a leader in natural resource accounting.

He kept a few head of livestock on his 80-acre farm, and according to his family, he was most at ease wearing jeans and boots on the farm. Herman Kocour died in Kansas at the age of sixty-five.

Lt. Anthony Evans

Almost nothing is known of Lt. Anthony Evans. He completed his fiftieth combat mission on August 28, 1943, a B-17 bomber-escort mission to Terni, Italy. He completed his tour with a bang, destroying an Me 109 on his final flight. Tony Evans was a very effective fighter pilot. He has been credited with four confirmed kills during his service in North Africa.

Lieutenant Evans’s orders sending him home to the States were received on September 26, 1943, and he joined many of his fellow pilots on the long homeward trek. From that point forward, no record is found.

The Bland Family

In the course of time, Bea and Grady Bland would later add two sons to their family, John and Bob. And in due course, Carolyn coped with the loss of her young husband, and like many young war widows, remarried. She settled with Jessica in Houston, and with her husband Joe added two more daughters to the family, Winifred and Janice. She and Joe were married until his death in 1995, and she died in May 2005.

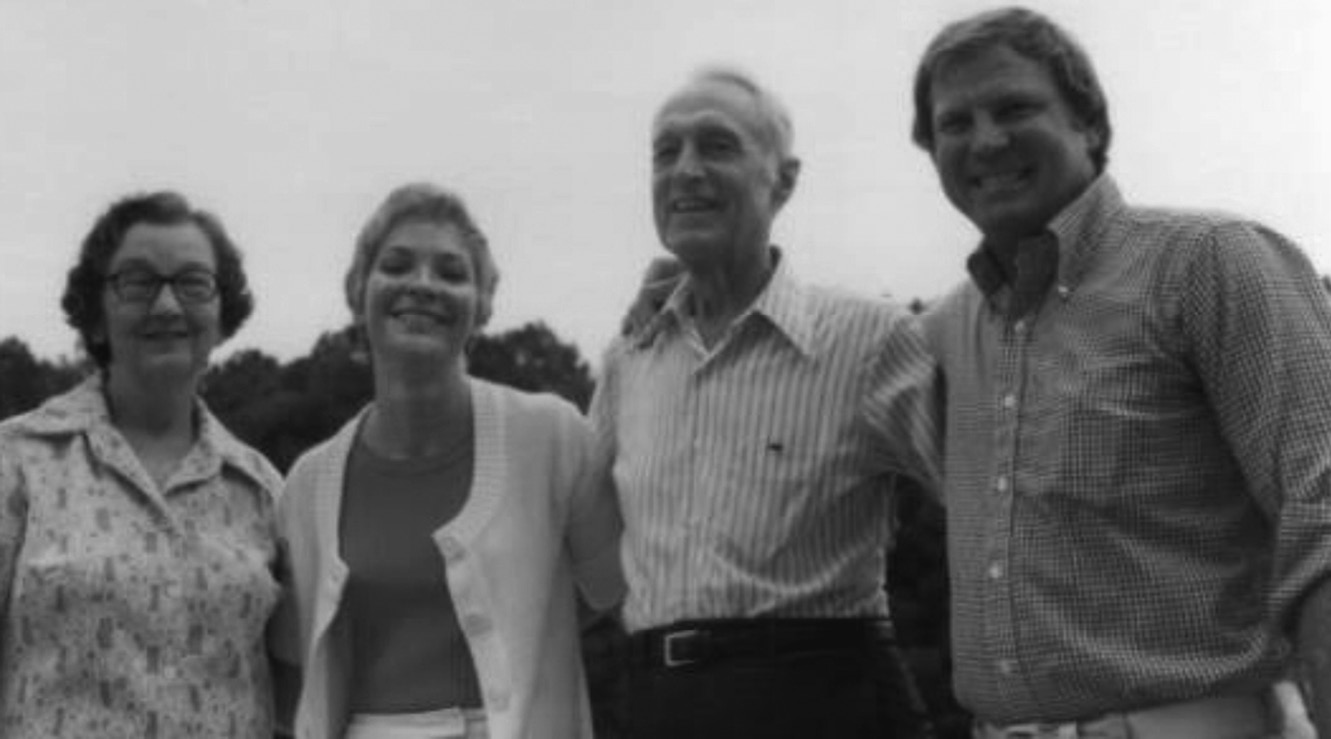

Wallace Bland’s parents, Bea and Grady Bland, with Carolyn (Bland) Clark and Joe Clark.

Art Taphorn

Lt. Louis Ogle

Lieutenants Louis Ogle and Martin Foster were assigned as spares to the mission of July 10, 1943, when Allan Knepper and Wallace Bland were killed. When Lieutenant Richard’s aircraft developed a mechanical problem, he peeled off the formation and Lieutenant Foster took his position as Lieutenant Decker’s wingman. Richard and Ogle escorted each other back to base.

Lieutenant Ogle got a lot of flying in during the month of July, assigned to eight more missions between July 10 and 30. He was absent from the squadron for the month of August, for reasons that are not known. He returned to action on September 6, just in time for the next major American offensive of the war—Operation Avalanche.

The invasion of Italy began on September 3 with Operation Baytown, in which the British Eighth Army jumped across the Messina Strait to occupy the toe of Italy. A second invasion force, code-named Operation Slapstick, landed at Taranto on September 9. The main invasion force, consisting of the American 5th Army, landed at Salerno on that day.

As with the landings on Sicily during Operation Husky, the Allied air forces were assigned the task of attaining air superiority and supporting the ground offensive. Accordingly, the pilots of the 49th squadron flew at a pace that was little noted during the months of June, July, and August.

Lieutenant Ogle was assigned to twelve missions in the nine days from September 6 to 15. On four of those days he flew two missions each, a heavy load of combat assignments shared by other members of the squadron.

On September 15 Ogle was assigned to a dive-bombing mission on the road between Baiano and Monteforte, Italy, having already flown a dive-bombing mission earlier in the day to Montecorvino. According to his fellow pilots: “As we were approaching Salerno after leaving the target area we encountered flak. While weaving to avoid this flak I saw a puff of black smoke come out of Lieutenant Ogle’s left engine. I looked away, watching the ground for a very short time, and when I next looked up I saw Ogle, apparently out of control, pull straight up and then over and hit the ground . . . in the town of Fisciana.”6

Incredibly, Lieutenant Ogle was the only casualty sustained by all three squadrons of the 14th Fighter Group during the Allied invasion of Italy. An experienced combat pilot at the time of his death, Ogle was killed on his eighteenth mission, and was buried at the U.S. Military Cemetery at Mount Soprano, Italy. In 1948 his remains were repatriated, at his father’s request, to his hometown of Pierce City, Missouri.

Capt. Lester L. Blount

Captain Blount remained with the squadron for nearly the entire war, and upon his return to the United States was assigned as psychiatrist at the El Toro Air Force Base. He narrowly avoided being reassigned to a combat unit in the Pacific Theater, and credited a compassionate clerk with “misfiling” his documents.

Maj. Lester Blount, probably photographed at Foggia, Italy.

BLOUNT FAMILY COLLECTION

After the war, Lester Blount restarted his medical practice at Santa Ana, California. That area was to experience unprecedented growth, and his practice grew along with it. He later returned to school to study surgery, and his wife, Barbara, returned to teaching.

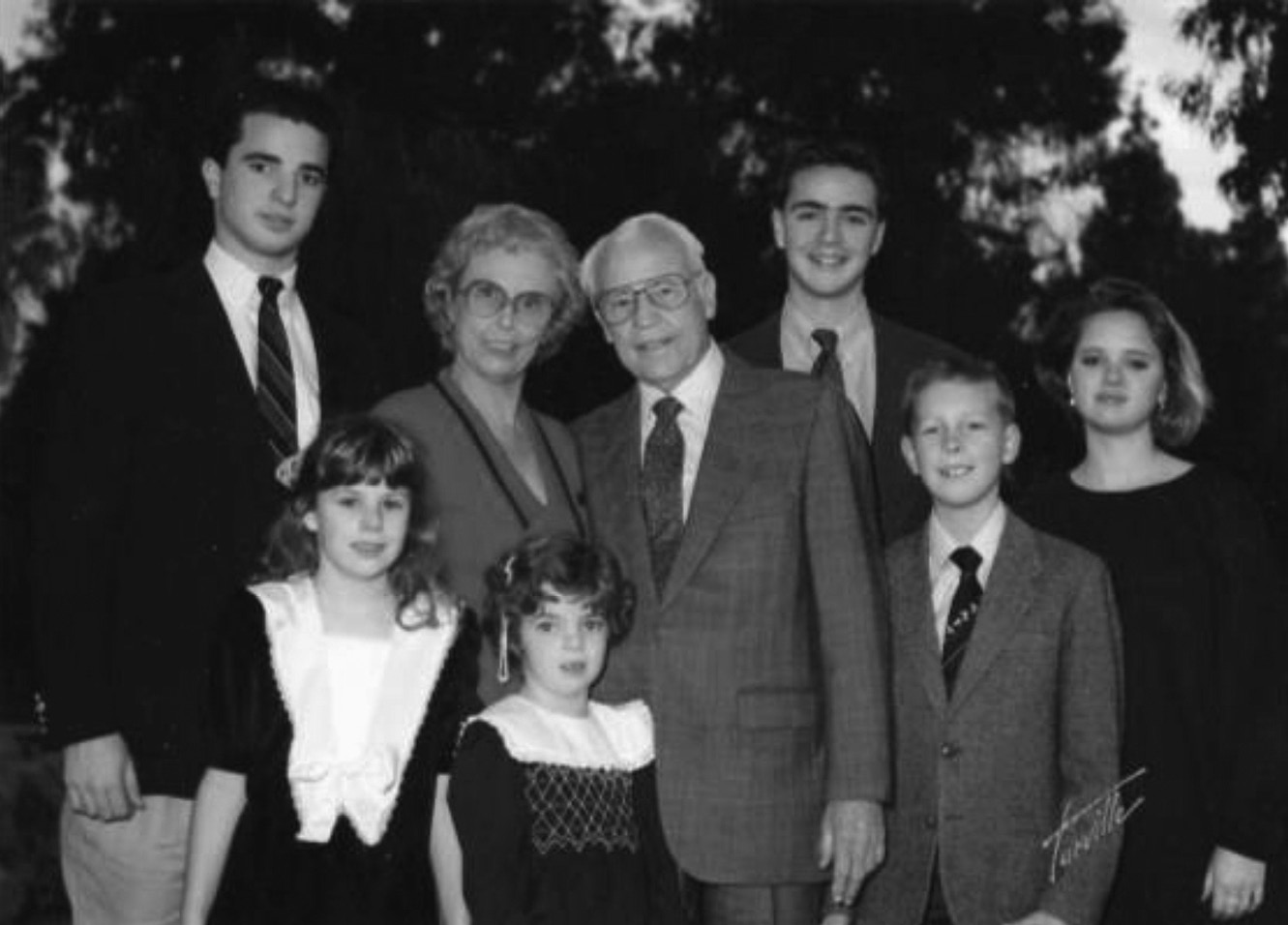

The three children of Lester and Barbara Blount: Gary, John, and Barbara Lynn.

BLOUT FAMILY COLLECTION

After the war, Dr. Blount continued his predilection for invention and pioneered the use of disposable plastic components for hospital use. Working out of his garage, and occasionally using his children as models for his pediatric prototypes, he developed the Blount Oxygen Mask, a pliant polyethene design that provided a closer and more comfortable patient fit.

Later, Dr. Blount became committed to not just limiting smoking in America, but to stamping it out. He developed the “Smoker’s Kit,” a smoking cessation system for which he received a patent and later commercialized.

Blount Oxygen Mask.

BLOUNT FAMILY COLLECTION

For several years, Dr. Blount and his son Gary would board a military surplus C-47 operated by Southwest Airlines and fly up the California coast, hopscotching airfields until they arrived at the grandparents’ home in Salina.

Lester and Barbara Blount, and family.

BLOUNT FAMILY COLLECTION

Lester was the sort of person who did not know how to slow down. On the day he was scheduled for his own cardiac surgery, he first completed hospital rounds to check on his patients. Dr. Blount did not recover from his own surgery, and died on March 3, 1988, at Santa Ana, California.

Maj. Henry “Hugh” Trollope

Maj. Henry Trollope, the commander of the 49th Fighter Squadron during the summer of 1943, a time of intense combat and high losses, flew his last mission with the squadron on September 19, 1943. Along with many of his fellow pilots, he received orders to return home on September 26. His service in North Africa resulted in his being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with eight oak leaf clusters. His travels home took him from North Africa through Rio de Janeiro to Miami, and by rail back to his wife Margaret in Casper. He arrived home on October 20.

On September 9, 1946 Hugh Trollope’s P-80 went down shortly after takeoff from his base, and he was killed in the crash. According to his family, a mechanical failure caused his “bucket wheel” to come off, destroying the aircraft’s stabilizer.

Major Trollope’s accident was one of many that occurred during the introduction of the P-80. America’s leading ace in World War II, Maj. Richard Bong, was killed during an acceptance flight of the P-80 in August 1945. In 1946 alone, eighty accidents were reported at home and abroad, with eight pilot fatalities.

Hugh’s twin brother Harry married, and christened his son “Hugh” in honor of his lost brother.