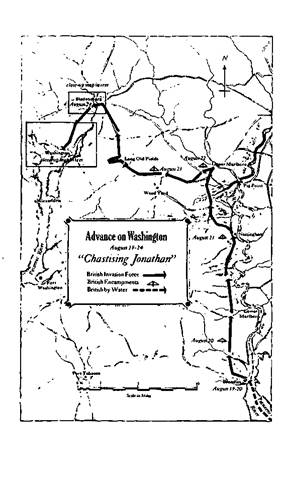

TWENTY MILES WEST OF Washington, the Reverend John A. Dagg—rushing with his militia company on August 25 to relieve the captured capital—began meeting frightened soldiers hurrying the other way. They assured him the British were right behind them.

Twenty miles north of Washington that same afternoon a man named Milligan burst into Brookeville, Maryland, with the news that the British had just burned nearby Montgomery Court House and were on their way to Frederick. At Montgomery Court House General Winder could see no sign of them, but he too felt he knew just where they were. “There remains no doubt but that the enemy are on the advance to Baltimore,” he wrote General Strieker of that city, “and will be tonight full half-way. . ..”

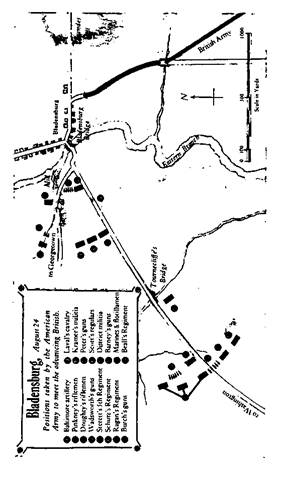

For his intelligence, Winder was still depending largely on Colonel McLane, the Collector of the Port of Wilmington, who during the past two days had consistently managed to place the enemy between himself and the American Army. McLane’s latest contribution was a flash that the British had brought their ships up to Washington and were landing 2,000 reinforcements at Greenleafs Point. Together with the “6 to 7,000” Winder felt they had at Bladensburg, the force bound for Baltimore was “overwhelming.” The General apparently missed or never got a copy of the new, concise report sent by Captain Henry Thompson, stationed on the road to Baltimore: “There is not an Englishman this side of Bladensburg.”

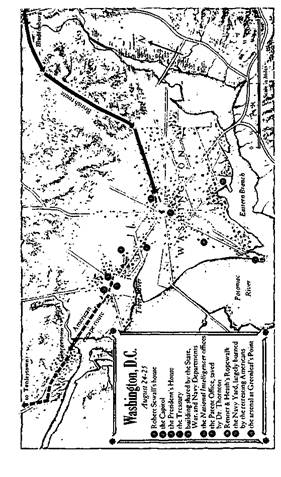

It was not surprising. The situation at headquarters verged on chaos. After reaching Tenleytown on the night of the 24th, Winder had paused, hoping to collect his shattered army. But the men melted away as fast as they came in, and by midnight the three miles separating himself from Georgetown, and maybe the British, began to seem very thin. By the light of the fires raging in the capital, he retired five miles farther west … then at dawn moved still farther back to Montgomery Court House, some 12 miles from the city. Here maybe he could make a respectable showing.

No such luck. Colonel Beall could muster only 100 of his 800 men from Annapolis … Sailing Master John A. Webster, only 50 of the 400 flotillamen. General Stansbury’s 1,400 militia from Baltimore County had all but vanished: there were only 15 or 20 left under the faithful Captain Edward Aisquith. Colonel McLane scoured the countryside in a fruitless search for others: “I find the road full of straggling militia looking toward Baltimore. I have prayed, I have begged, I have threatened, all to no purpose. Those drones on the public persist in running away…. From a disorganized militia, Good Lord deliver us.”

The Colonel might also have prayed for a quartermaster. The army’s baggage train had strayed off to Virginia; there was no bread, no meat, no tents, no supplies of any kind. Turning up at Montgomery Court House during the afternoon, Jacob Barker and Robert de Peyster were appalled by the situation. Worse, nobody seemed to be doing anything about it. Hurrying to Baltimore, they sent back five or six wagons loaded with all the hard bread they could find—paid for completely out of their own pockets. Meanwhile Winder dashed off a frantic plea to Secretary Armstrong in Frederick to send flour and salt beef … making sure, he added, to pick a route safe from the ubiquitous British.

Armstrong did his best, but he was “somewhat indisposed” and thoroughly disgusted. Through his aide Major Daniel Parker, he sent a caustic message to Major General Samuel Smith of the Maryland Militia, hoping a better defense would be made at Baltimore than at Bladensburg—”that story will not tell well.” More bitter than ever at the course of events, the Secretary now had a new cause for complaint. He and Secretary of the Treasury Campbell had gone to Frederick, specifically designated by Madison as the place where the government would reconvene, and now nobody else was coming.

Certainly it was the last thing on the President’s mind. He and Dolley Madison spent most of the 25th still floundering around the Virginia countryside looking for each other. During the morning Madison had ridden from Salona back to Falls Church, hoping to find his wife at Wren’s Tavern. She meanwhile had left Rokeby and visited Salona in hopes of catching him. Neither, of course, had any luck. Mrs. Madison then continued west to Wiley’s Tavern on Difficult Run, while the President returned to Salona to learn she had just left. He immediately set out after her but was held up along the way by the great storm that swept the area that afternoon. Madison finally reached Wiley’s toward the end of the day, and here at last he found the First Lady.

Both were still traveling with their respective parties, but there was little time for reunion. Midnight, Madison set out again—now with Rush, Jones, Mason and the State Department chief clerk John Graham—planning to cross the Potomac at Conn’s Ferry and rejoin Winder in Maryland. When it proved impossible to cross at night, Jones went back to look after the ladies, while Madison and the others waited till dawn of the 26th. It was 6:00 P.M. by the time they wearily rode into Montgomery Court House, only to find that Winder was no longer there. Taking such men as he could, the General had started for Baltimore around noon.

The Presidential party, now escorted by a troop of dragoons, picked up the trail. But it proved impossible to catch up with Winder that night. Around 9:00 P.M. they finally halted at Brookeville, eight miles farther on. This was a small Quaker community—normally a quiet, idyllic retreat—but for the past week it had swarmed with refugees and troops. Yet somehow the town never lost its composure. As Mrs. Caleb Bentley told one of her unexpected guests while spreading the table for a fourth or fifth time in a single evening, “It is against our principles to have anything to do with war, but we receive and relieve all who come to us.”

Nor was it any different when the nation’s Commander-in-Chief asked to spend the night. All hands went to work in the Bentley kitchen; beds were spread in the parlor; campfires were kindled in the yard outside. The villagers filed in to pay their respects, and the President received them gravely.

At 10:00 P.M. he found a moment to dash off a quick letter to James Monroe, who was now with Winder’s force, camped at Snelt’s Bridge several miles closer to Baltimore. Madison always felt safer in matters of war when Monroe was around, and this time was no exception: “I will either wait here for you to join me, or follow and join you, as you may think best.… If you decide on coming hither, the sooner the better.”

Monroe was thinking along the same lines. He too felt military matters were handled better when he himself was around. And on top of that, nothing seemed more dangerous than this fragmented government—the President and the Secretaries of State, War and Navy in four different places. His love of action had carried him along during the day. Winder had been so sure the British were marching on Baltimore … had even gone ahead to get everything ready for the troops. But new reports were coming in suggesting that the General was off on another false scent.

The latest dispatches said that the enemy were definitely heading back to their ships … that serious disorders were breaking out in the abandoned capital. Worst of all, there were rumors of that perennial nightmare in times of crisis—a slave rebellion. General Robert Young, bringing reinforcements from Fairfax County, was already holding up his men on the south side of the Potomac. General Walter Smith’s District Militia and Major Peter’s Georgetown artillery were clamoring to get back to protect their homes in Washington.

Everything seemed to call for strong central authority. Early on the morning of August 27—even before Madison’s letter reached him—Monroe wrote the President, urging they return to Washington at once. Then he turned up himself at Brookeville to drive home the point, but Madison needed no prodding. On receiving Monroe’s letter, he had immediately written Jones, Armstrong and Campbell to hurry back. Then a special note to Dolley—“my dearest”—assuring the group at Wiley’s Tavern that Washington was safe again. “We shall accordingly set out thither immediately; you will all of course take the same resolution.”

At noon they started out: the President; the faithful Richard Rush; the self-assured Monroe; and the guard of 20 dragoons, jangling in martial splendor—an almost ludicrous touch in the light of the past week’s shambles. Behind lay the smiling Bentleys and the tranquillity of Quaker Brookeville. Ahead lay the chaos and uncertainty of the ravaged capital. Nobody knew what to expect. “I know not where we are in the first instance to hide our heads,” Madison confessed in his note to Dolley, “but shall look for a place on my arrival.”

An almost eerie quiet hung over Washington; it had been that way ever since the British left. Pennsylvania Avenue stood broad and empty, with Joe Gales’s type still scattered over the 7th Street intersection. General Ross’s horse still lay, legs stiff in death, outside the ruins of Robert Sewall’s house. The rubble of the Capitol still smoldered quietly in the sun. Contrary to all the wild rumors, there was no slave rebellion—the blacks still wanted no part of either side—but here and there occasional figures did dart in and out of the deserted buildings.

Looters. The capital’s poor had always been a problem. Largely drifters and unskilled hands brought in to work on the public buildings, they had been left high and dry when the projects were finished or the money ran out. Even in good times they seemed to “live like fishes, by eating each other,” to quote one shrewd observer, and these were anything but good times. The empty buildings … the disappearance of all authority … a sense of the waste of war in the air … all brought out the worst in them regardless of race. Once it was clear the British were gone and the American government not yet returned, they quickly went to work.

Alexander McCormack’s groceries … a case of domestic striped shawls left at Long’s Hotel … the contents of Congressman Abijah Bigelow’s desk at his boarding-house—anything was fair game. The files in the War Department’s fireproof vault survived the British Army, but not the town’s own looters. They continued to run wild at the Navy Yard, where they not only broke open Captain Tingey’s locked door but took the lock itself.

This wholesale plundering was in full swing on the morning of August 26, when Dr. William Thornton returned to the city. The colorful Superintendent of Patents had saved his building the day before; now he was back to make sure it was still standing. It was; but a quick look around convinced the doctor that there were plenty of other problems to tackle.

Thornton was not a shy man. Realizing he was the only functionary in town, he quickly appointed himself a sort of unofficial mayor. (For his authority he later recalled that he had once been named a justice of the peace.) Plunging into his new role, he appointed guards at the ruins of the various government buildings. He shut the gates of the Navy Yard. He visited the British wounded at Carroll Row. He established useful relations with Sergeant Robert Sinclair of the 21st Foot, who had been left in charge of them. He waited on Dr. James Ewell, “to thank him in the name of the city for his goodness toward the distressed, who, being in our power, and especially in misery, were no longer enemies.” He appointed a commissary to look after the injured’s needs. He appointed citizen guards to patrol the streets at night. He made an odd arrangement with Sergeant Sinclair to include British soldiers in these patrols.

About 3:00 P.M. Dr. James Blake, Washington’s official Mayor, returned to the city. Embarrassed at getting back so late, he failed to appreciate the ceremonial flourish with which Dr. Thornton handed over his borrowed authority. Nor did he like Thornton’s idea of using captured enemy soldiers to help guard the capital. Backed by a citizens’ meeting, Blake rejected the plan and set up his own system of patrols. The individualistic Thornton retired in a huff and thereafter contented himself with taunting letters to the editor about mayors who disappeared in times of crisis.

But once again Thornton had risen to the occasion. Now the job was done. The looting stopped. Order restored. Around dusk Captain Caldwell’s cavalry turned up, adding the reassuring sight of American uniforms; and Mayor Blake himself walked the streets all night, his musket at the ready. By 5:00 P.M. on August 27, when the Presidential party re-entered Washington, all was quiet in the city.

Not so down the Potomac. The rumble of distant gunfire came drifting up the river. It was clearly that British naval squadron, so often reported, yet all but forgotten in the recent excitement. Was the city now in for a new set of horrors? The rumble ominously continued for about two hours. Then, around 8:30, came a deep, teeth-rattling explosion. It shook the ruins of the Navy Yard, where Captain Tingey was toting up a list of losses. It rattled the windows at the Thorntons, where they were excitedly exchanging experiences with the Cuttses and other neighbors. It broke in on the quiet, serious conversation at Secretary Rush’s house, where he, Madison and Monroe were assessing the military and political situation. The whole city seemed to pause … and listen for what would come next. But there was nothing—just silence.

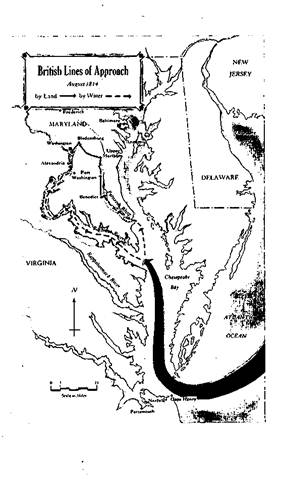

On the quarterdeck of the frigate Euryalus Captain Charles Napier studied Fort Washington and tried to figure what the explosion meant. The British diversionary squadron under Captain James Gordon had been inching up the Potomac for ten days now, fighting shoals, current and contrary winds. Far behind schedule, the men watched the glow in the sky on the 24th and guessed correctly that Washington had already fallen. They kept on anyhow. They might come in handy if the army ran into trouble on the way back. But it was hard work, and now this big fort, looming high on the Maryland side, looked like the biggest obstacle of all.

They had been bombarding it for two hours when Captain Napier saw to his surprise that the garrison was retiring—and then this appalling, earth-shaking explosion. The British guns fell silent as the crews watched a great mushroom of smoke rise over the equally silent fort. It was too late in the evening to investigate, but it looked as though the defenders had blown the place up.

To Napier, it seemed incredible. The position was good; its capture would have cost at least 50 men. Moreover, the winds were so much against the British that a serious check could have upset the whole expedition.

Yet the incredible had happened. Captain Sam Dyson, commanding the 60-man garrison, had orders from Winder to blow up his fort and retire, if attacked by land. Of course he wasn’t being attacked by land, but he heard rumors of troop reinforcements coming ashore on the Patuxent, and he feared he might be caught between them and this squadron on the river. It wasn’t a very convincing story—and didn’t sit at all well with the court-martial that later convened—but that was the way he told it. In any event, Dyson spiked his guns without firing a shot, led out his men, and set off the 3,346 pounds of powder in the fort’s magazine.

Coming ashore early the following morning, the British toted up their good fortune: 27 guns, 564 cannon balls, countless small arms and ammunition. Best of all, the way was now completely open to the rich port of Alexandria, only six miles farther upstream.

Others realized this too. As the squadron got under way again, down the river from Alexandria came a small boat flying a flag of truce. Around 10:00 A.M. it eased alongside the frigate Seahorse, flagship of the expedition, and three of the town’s leading citizens climbed aboard the warship. They were led to Captain Gordon’s cabin, where the Captain asked politely what he could do for them.

Jonathan Swift, spokesman for the group, began by saying that when the British reached Alexandria, he hoped that Gordon would show as much respect for private property as Admiral Cockburn and General Ross had displayed in Washington. They had “immortalized their names” and here was a fine opportunity to emulate their splendid example.

Captain Gordon said dryly that he didn’t need any prompting to do what was right. Pressed for details, he said he would respect shops and houses but planned to seize all ships and cargoes waiting for export. Most unfair to Alexandria, Swift pleaded. The citizens were “all Federalists,” yet they were being made to suffer far more than those people in Washington.

Gordon remained unmoved. Nor would he say exactly what his surrender terms were. Everyone would find out once he arrived.

The disappointed delegation went back to Alexandria, where the Committee of Vigilance was already doing its best to soften the town’s fate. The biggest danger seemed to be that someone might try to rescue them. This could easily lead to shooting and incur the wrath of the British commander. The man to watch was clearly Brigadier General John P. Hungerford, whose 1,400 Virginia Militia were hurrying toward them, only 24 miles away.

The committee whipped up a resolution, urging Hungerford to lay off. It explained that Alexandria had no military force to protect it, that the committee intended to surrender at discretion, “and therefore think it injurious to the interests of the town for any troops to enter at this time.”

The upside-down logic of urging the relief force to stay away for fear of spoiling the surrender seemed lost on the committee, but it overwhelmed Lieutenant Colonel R. E. Parker, the officer in Hungerford’s command who first got the message. Passing it on to the General, Parker added his own postscript: “I send you a copy of an instrument just received and make no comment on it—my heart is broke.”

Meanwhile Captain Gordon’s squadron crept closer. At 7:00 P.M. most of the ships anchored about two miles south of Alexandria, but the bomb vessel Aetna continued up, standing ominously off the town at dusk.

At 8:30 P.M. the Committee of Vigilance decided to try their luck with Captain Gordon again. This time they chose a local businessman named William Wilson as their spokesman. His firm had close commercial ties with England and perhaps that might do some good. Wilson went aboard the Seahorse at 9:30, pleaded the town’s cause for three hours, but Gordon remained unimpressed.

Monday morning, August 29, the British squadron drew opposite the waterfront, turned its guns on the town, and this time Captain Gordon delivered his terms in the most specific manner possible: all naval stores, public or private, to be delivered up; all scuttled vessels to be raised and handed over; all goods intended for export to be surrendered; all goods sent out of town since August 19 to be retrieved and given up; all necessary provisions to be supplied the fleet, but at current prices. The crisp English officer who brought the terms told Mayor Charles Simms that he had exactly one hour to accept them.

The Committee of Vigilance briefly wrangled over a couple of points. They couldn’t make the citizens raise their own scuttled ships; they couldn’t retrieve the goods already sent out of town. Very well, the officer said, he would make those concessions—but nothing else.

The committee quickly capitulated. Gordon’s ships eased alongside the wharves, and for the next three days the sailors scurried back and forth, salvaging the scuttled boats and loading the rest with the flour, beef and tobacco that filled Alexandria’s warehouses. There was no friction: the town’s merchants watched sadly from a distance, while the English tars conducted themselves perfectly. “It is impossible that men could behave better than the British behaved while the town was in their hands,” Mayor Simms wrote his wife a few days later with just a little too much enthusiasm.

Alexandria wanted only to keep things pleasant, and for that reason it was all the more disturbing when the city fathers learned on the 29th that General Hungerford was hurrying to save them in spite of their resolution. His force was now only ten miles away. Once more the Committee of Vigilance sent out a messenger to him—this time not with a mere resolution, but with an order not to come any closer and interrupt their arrangements with the enemy. Hungerford answered coldly that he acted only under the authority of the federal government … and kept marching. No one knows what might have happened had he reached the town, but when only three miles away, he received new orders from Washington to halt where he was and detach some of his men for other duties.

So that hurdle was past, but a new crisis arose on September 1—due, strangely enough, to a joke. That afternoon two of the U.S. Navy’s real fire-eaters—Commodore David Porter and Captain John O. Creighton—were lurking not far from Alexandria when they heard that some British officers were dining there at Tripplett’s Hotel. Hoping to seize them by surprise, Porter and Creighton came galloping into town on horseback, but some Tory warned the officers and they escaped in time.

Still hoping to stir a little mischief, the two American captains now rode to the waterfront. Here they spied a young British midshipman, John West Fraser, who was supervising a work detail loading one of the captured ships. Roaring up from nowhere, Creighton seized Fraser by his cravat and tried to carry him off. It was an unequal struggle—the Captain was a remarkably burly man and Fraser “perhaps 14 years old—but as luck would have it, the midshipman’s cravat broke, and he scrambled to safety aboard the ship.

Instantly the alarm gun sounded … the Seahorse hoisted a signal to prepare for battle … the sailors hurried to their action stations … and the squadron’s guns were once again trained on Alexandria. Women and children fled through the streets, and Mayor Simms frantically scribbled out an apology while a British officer stood at his elbow with the buffeted midshipman in tow.

A delegation soon made its way to the Seahorse conveying official regrets: the town had no control over the perpetrators of the outrage … it shouldn’t be held responsible … it would take steps to see such a thing didn’t happen again … guards would be posted at the head of each street leading to the waterfront. Finally mollified, Captain Gordon annulled his signal for battle stations, and Alexandria heaved a huge, collective sigh of relief.

“Alexandria has surrendered its town and all their flour and merchandize,” Margaret Bayard Smith wrote her sister from Washington on August 30. “What will be our fate I know not. The citizens who remained are now moving out, and all seem more alarmed than before.”

The capital trembled at the thought of another enemy visit, and indeed there seemed no reason why the British couldn’t bring their boats and barges six more miles and complete the job Ross and Cockburn had begun. To French Minister Serurier the threat posed a delicate diplomatic problem. “Your Highness will understand,” he wrote Talleyrand in Paris, “that I do not wish them to find me a second time in this residence, and find myself having to give dinners to their generals or squadron leaders. To avoid this possibility, I am thus determined, my Lord, to leave tomorrow for Philadelphia….”

And how would he explain this runaway to the Americans? It would be easy: “Upon leaving, I shall say to the people of Washington that I stayed with them as long as they were in danger, but now that danger is past, I am going to travel for a while….”

Such deviousness wasn’t necessary. Most of Washington not only expected the British again but wanted to surrender in advance. “The people are violently irritated at the thought of our attempting to make any more futile resistance,” Mrs. William Thornton noted in her diary on the 28th.

That same morning the irrepressible Dr. Thornton buttonholed Mayor Blake. The time had come, he urged, to send a deputation to the British fleet at Alexandria and ask for terms. There was nothing wrong with Thornton’s courage—he had proved that—but as a practical man, he wanted to save the rest of the city, and as a good Federalist, he saw no salvation in Madison’s hands.

The Mayor brushed him aside, and Thornton next went to the President himself, who was returning from an inspection of the Navy Yard with James Monroe and Richard Rush. The people, Thornton began, wanted to capitulate. Madison rejected the idea, but Thornton pressed on. The citizens had a right to surrender, he said, notwithstanding the presence of the government.

That was enough for Monroe. With Armstrong and Winder both miles away, the President had put him in charge of the whole defense effort. Turning to Thornton, he declared he had the military command, and if he saw any delegations proceeding to the enemy, he would bayonet them.

This put an end to it. Since the government was determined to resist, Thornton would do his best. The next time his wife saw him, she was distressed to find him buckling on his sword to go out and fight.

Monroe was the catalyst. Full of energy, he seemed to be everywhere at once. He had a battery planted on Greenleaf’s Point, another near the half-burned Potomac Bridge, a third at Windmill Point—all aimed down the river. He soon had the demoralized Georgetown volunteers posted on the heights above the town, and backed them with 300 to 400 Alexandria militia, who never had the opportunity to defend their own homes.

He sent orders to a colonel across the river to shift his guns to some better positions for engaging the enemy. When the colonel questioned his authority, Monroe rode over and gave the order in person. The colonel remained adamant, and Monroe told him to obey or leave the field. The colonel left, but the guns were moved.

A new spirit filled the capital. Monroe was firm, confident, respected, well known, and above all trusted. In this last respect, ironically enough, he was guilty of one significant lapse. He carefully concealed his role in forming the disastrous battle lines at Bladensburg. Writing his friend George Hay at this time, he confided that this was. something “which I mention in particular confidence, for I wish nothing to be said about me in the affair.”

But good men too occasionally stumble, and at the moment it was perhaps just as well that James Monroe’s deception went undetected. What the capital needed more than anything else was faith, and this he supplied in generous measure.

Washington got another lift with the return of Navy Secretary William Jones on the afternoon of the 28th. He had left Mrs. Madison, and his own family in Virginia, crossed into Maryland in a vain effort to catch up with the President, and finally arrived alone from Montgomery Court House. Now he was full of optimistic ideas on using the navy. Seeing an opportunity to trap the British up the Potomac—or even capture their ships if they tried for Washington—he ordered Commodore John Rodgers, marking time in Baltimore, to hurry down with “650 picked men.”

But for Madison personally, the best lift of all came with the unexpected return of “my dearest” Dolley on the afternoon of the 28th. She had started right out on receiving his message from Brookeville, attended by Navy Department clerk Edward Duvall. She never got a second note, warning her to hold off, and now came riding into town in a carriage belonging to Richard Parrott, the Georgetown ropewalk owner. Rolling past the ruins of the President’s House, she went straight to the Cutts home on F Street. It must have been a strange feeling—this was where she and Madison lived when they first came to Washington in 1801.

The President met her there, and they decided to stay with the Cuttses until more permanent arrangements could be made. The news quickly spread that the First Lady was back, and the Thorntons and Smiths dropped by to pay their respects. It was a different Dolley Madison they found. For once her sunny warmth was missing. She was depressed—could hardly speak without tears—and almost violent on the subject of the English. A few troopers passed by, and she exclaimed how she wished for 10,000 such men “to sink our enemy to the bottomless pit.”

August 29, and two more familiar figures appeared—Secretaries Campbell and Armstrong, back from their futile trip to Frederick. Campbell was seriously sick and soon resigned his post. Armstrong, active and ready for business, discovered that the whole capital was against him. Always detested by the Federalists, for months he had barely been suffered by the Virginia-oriented Democrats. Now both factions declared him the architect of the “ disaster.

He was blamed for everything. Forgetting the President’s uninspired leadership, Winder’s appalling generalship and all the other contributing causes, most people saw only John Armstrong’s misassessments—and in these they even saw treason. A torrent of false charges poured on him. He was said to have lost Washington deliberately in a plot to move the capital north. He was said to have ordered Captain Dyson to blow up Fort Washington without firing a shot. He was said to have been in touch with a relative in the advancing British Army. He was said to have drawn a million dollars from the Treasury the day before Bladensburg, planning to join the army on the Canadian front and seize the reins of government. “The movements of this fiend should be narrowly watched,” warned the Georgetown Federal Republican.

In his proud way, Armstrong tried to ignore it. On the afternoon of his return, he rode down to Windmill Point, intending to inspect the District Militia. His appearance set off an uproar. Apart from politics, the officers were mostly men of property with heavy investments in Washington. They shuddered at the thought of Armstrong trying to move the capital. Charles Carroll of Bellevue, one of the largest landholders, refused to shake hands; various officers laid down their swords rather than serve under him; and as their version of this chivalric gesture, the enlisted men working on the ditches threw down their shovels.

Either at this time—or even earlier—General Walter Smith’s 1st Brigade held a meeting at which the men passed a formal and unanimous resolution: they would no longer serve under Armstrong, that “willing cause” of the city’s capture. Smith hastily sent his aide Thomas McKenney and his brigade inspector Major John S. Williams to alert Madison, adding his assurance that “under the orders of any other member of the cabinet, what can be done, will be done.”

The President sent back word that he would give the matter his “immediate, deliberate, and earnest consideration.”

That evening Madison dropped by the Seven Buildings for a quiet talk with his Secretary of War. Feeling was running high against them both, the President began, but especially against Armstrong. It would be best if he didn’t go near the local troops. In fact, a message from General Smith indicated that “every officer would tear off his epaulets” if he had anything more to do with them. Monroe got along with them nicely, Madison added tactlessly; the Secretary of State had been doubling as Secretary of War, but with Armstrong’s return, that expedient was out. They must think of something else.

Armstrong took all this to mean that the President was proposing some other person—undoubtedly Monroe—to handle the situation in the District, while he continued as Secretary of War for everywhere else. Remarking that the feeling against him was all based on lies, he went on to say he obviously couldn’t remain in the capital with part of his functions exercised by someone else. He must exercise his whole authority or none at all. If he couldn’t do the job effectively, he’d resign … or perhaps retire from the scene and visit his family in New York.

The President felt resignation was going too far—it might have a bad effect—but he rather took to a “temporary retirement.” Then, after a long but dignified argument over Armstrong’s share in the recent disasters, Madison closed the conversation by going back to the Secretary’s offer to visit his family for a while. Tomorrow morning, nudged the Chief Executive.

Next morning, as anticipated, John Armstrong was off … but it would still be some time before he got to New York. For most of four days he smoldered in Baltimore, spilling out his anger to friends. The more he thought about it, the more outrageous the charade seemed. Finally on September 3 he announced his resignation in a long, stinging letter to the Baltimore Patriot and Evening Advertiser. Perhaps as a deliberate slight, he confirmed it on the 4th in a curt, two-sentence note to Madison.

With Armstrong gone, the President immediately named James Monroe as Acting Secretary of War, and the change was noticeable at once. Monroe’s first move was to try and trap the British at Alexandria. To accomplish this, he had some Virginia Militia, several District units anxious to redeem themselves, and Commodore Rodgers’s “650 picked men,” just summoned from Baltimore. More important than the men themselves, he had three highly enterprising naval officers to manage the effort: Rodgers, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and Commodore David Porter. All were established national heroes and proven gunnery experts.

The plan was simple: place batteries along the Potomac below Alexandria and pound the British as they returned down the river. But it took time to haul the guns to the selected positions—and even more time to plant them. Long before the Americans were ready, the British at Alexandria smelled danger. At 5:00 A.M., September 2,Captain Gordon’s flagship Seahorse slipped her moorings and began working downstream. The rest of the squadron followed, and with them went no less than 21 prize vessels. Their decks bulged with 13,786 barrels of flour, 757 hogsheads of tobacco, and countless tons of cotton, tar, beef and sugar.

The following morning, the 3rd, Commodore Rodgers left Washington in hot pursuit. Boiling down the Potomac with a small flotilla of cutters, he hoped to send three fire vessels against the tail end of the British squadron. There was a brief pause opposite Alexandria when he noticed that the town fathers of that docile community hadn’t yet put back the American flag. This fixed, he hurried on and caught up with the enemy around noon. He seemed to be in luck: the bomb ship Devastation had run aground and looked like an easy mark.

But then luck failed. The wind died, and Captain Thomas Alexander of the Devastation turned out to be a most resourceful opponent. He pushed off his own cutters and barges, breaking up Rodgers’s attack and scattering the American boats. John Moore a young midshipman from the Seahorse, towed the nearest fire vessel ashore, and the others were easily turned aside. Rodgers later tried again with two more fire vessels, but had no greater success. Such a weapon was child’s play for men who had spent 20 years battling Napoleon.

The British ships up front had more serious trouble. They soon came up against Commodore Porter’s batteries posted at the White House, a bluff on the Virginia shore. By September 3 he had ten guns in place, a furnace for heating shot, entrenchments for his supporting infantry, and a huge white banner proclaiming in bold letters, “FREE TRADE AND SAILOR’S RIGHTS.”

Taking no chances, Gordon sent several of his ships ahead to soften Porter up, while the rest hung back, collecting under the guns of his two frigates for an all-out dash. All the 4th and the morning of the 5th the two sides traded hundreds of cannon balls with remarkably little effect. The log of the Erebus recorded one of the few dark moments: “Found one cask of rum shot through … lost 50 gallons.”

Noon, September 5, and Gordon was at last ready. Noting that the British trajectory was usually too low to reach the Americans high on their bluff, he added an almost Nelsonian touch: he weighted his ships to port so his starboard guns would fire higher. Then the Seahorse and Euryalus advanced, with the prizes and smaller vessels trailing behind. Soon all the British warships were pounding the bluff, and now their shots began to tell. Porter’s men hung on for an hour and a quarter, but it was a hopeless mismatch—13 effective guns against a combined naval broadside of 63 pieces. Knowing he couldn’t stop the enemy and seeing his own men starting to fall, Porter withdrew as Gordon sailed triumphantly by.

But the British commander’s troubles weren’t over. A little farther down the river on the Maryland side, Commodore Perry was waiting for him with some more guns planted at Indian Head. Gordon expected another long duel, but it turned out to be short and easy. The Americans had only one gun heavy enough to do any damage, and it soon ran out of ammunition. Early on the morning of the 6th Gordon sailed by unmolested and continued on his way.

For a badly shaken Washington there was only one consolation. The second British diversion—Sir Peter Parker’s foray up the Chesapeake in the frigate Menelaus—suffered an unexpected setback. The dashing Captain had an easy time of it the first two weeks, but then overreached himself. On the night of August 30 he landed near the village of Moorfields on Maryland’s Eastern Shore and led a party of marines and seamen against a strong force of local militia. Parker hoped to take them by surprise, but they were more than ready for him. The British attack collapsed under a withering fire.

Next morning a young American soldier exploring the battlefield came across an exquisitely made leather shoe neatly marked by a London booter: “No. 20169, Parker, Capt., Sir Peter, Bt.” Returning it during a truce that day, a militia officer remarked, “We guess that your captain was not a man to run away without his shoes.”

The hunch was right. Sir Peter Parker—reckless sailor, ruthless disciplinarian, spoiled child of patronage, but no less a hero to his men—had been mortally wounded during the attack.

Victory-starved Americans treated this single death as a major military stroke. The British cooperated with wildly exaggerated lamentations. In these golden days of aristocracy, the nobleman who fell in battle could generate an almost ritualistic outpouring of national grief. An authorized biographer depicted Parker, smiling as he fell, urging his men onward; actually, he only managed to gasp a rare piece of wise advice: “Pearce, you had better retreat, for the boats are a long way off.” Parker’s first cousin, Lord Byron, wrote a touching eulogy grieving for his departed comrade—while privately confessing that he hardly knew the man and “should not have wept melodiously except at the request of friends.”

Yet in the last analysis, Sir Peter Parker’s misfortune was a small affair for both British and Americans. The overwhelming fact was the capture of Washington … and now, the surrender of Alexandria. For Madison and his advisers this latest disaster was especially humiliating—in some respects even worse than Bladensburg. This time they knew what the enemy was doing; they had a Secretary of War they trusted; they had three of their most exciting commanders in the field; they far outnumbered the foe—and still they couldn’t win.

But at least the British were no longer breathing down their necks. Washington could start picking up the pieces. Captain Tingey set about recovering the hardware looted from the Navy Yard. The National Intelligencer advised its readers that Admiral Cockburn had not succeeded in destroying the paper’s account books, and subscribers were expected to pay up. The city’s hard-working doctors turned to the task of healing the wounded—both friend and foe. Some of the British casualties, in fact, became pampered favorites, Colonel Thornton received a bedpan from his namesake Dr. Thornton, and when the English surgeon Dr. Monteath died, Dr. Ewell asked for the Marine band to play at the funeral.

Some 120 British prisoners posed a more difficult problem. Many claimed to be deserters, and it was hard to say for sure. To be on the safe side, General Mason sent them all to Frederick, where those who made a convincing case were parceled out in pairs to interior towns like Leesburg, Winchester and York.

Meanwhile the hunt began for spies and traitors who might have helped the British achieve their lightning coup. To the stunned administration leaders, there had to be some better explanation than their own ineptitude. The Washington jail soon housed suspects like Richard H. Lee, charged with supplying the enemy with melons and useful intelligence … Peter Ramsay, said to have guided the invaders around the city … William Wilson of Alexandria, who showed too much interest in Commodore Porter’s fortifications down the Potomac … L. A. Clark, an enterprising purveyor of refreshments to thirsty American soldiers. “It is a most horrid thing,” Clark wrote General Winder on August 28, “that I should be kept under guard, supposing I piloted the enemy into Marlboro on Monday last, when it is known by Capt. Buck, Capt. Carberry, Lt. Rodgers, and a number of the officers of the 36th Regt. that I was at the Wood Yard on that day selling liquors.”

Presumably Mr. Clark’s loyal customers rallied to his side, for all the suspects were soon released. In the excitement of the chase, the hunters missed some genuine if rather small game—Ross’s informants Calder and a shadowy figure named Brown … Thomas Barclay’s clerk George Barton, whom chance placed so fortuitously at Bladensburg.

Along with the mopping up, Washington turned to the challenge of resuming normal government functions. Obviously, those cracked and blackened walls that studded the city would no longer do, yet it seemed all-important to get going again. To Madison and the administration leaders, it was a matter of re-establishing confidence, of getting on with the war. To the local inhabitants, it was all that and their pocketbooks too. Already the old cry was going up again to move the capital. Heavy investors like John P. Van Ness shuddered at the thought, and even the clerks and grocers knew that government was the town’s only industry. Things had to happen fast.

The President and Mrs. Madison moved into the Cutts house for a month … then to John Tayloe’s far more imposing Octagon House, now vacated by French Minister Serurier. The government departments were established in various private homes, and Congress in Blodgett’s Hotel, displacing the Post Office and Patent Office. But any hope that a truly useful role had finally been found for this white elephant of a building quickly vanished. The Representatives and Senators couldn’t stand the hot, cramped quarters and again began talking about moving the capital. Daniel Carroll, Thomas Law and other leading landowners hastily put up a Targe brick hall near the ruined Capitol, and here in the so-called “Brick Capitol” the legislators were happy again. An important crisis was past.

Gradually, the various departmental valuables and papers were brought back from their hiding places in the country. The “Gilbert Stuart” was retrieved by Jacob Barker. The navy’s trophies were unloaded from Benjamin Homans’s canal boat. The Library of Congress books were gone forever, but Thomas Jefferson sold his personal library to the government to form the nucleus of a new collection.

Buried among the salvaged War Department files was a single letter that might have changed everything. Dated July 27, 1814, it was addressed to “the Honourable James Madison” and came from an anonymous seaman, apparently impressed on one of Admiral Cockburn’s ships. Obviously sent at the risk of the writer’s life, it warned the President that

Your enemy have in agitation an attack on the capital of the United States. The manner in which they intend doing it is to take the advantage of a fair wind in ascending the Patuxent; and after having ascended it a certain distance, to land their men at once, and to make all possible dispatch to the capital: batter it down, and then return to their vessels immediately. In doing this there is calculated to be employed upwards of seven thousand men. The time of this designed attack I do not know….

(Signed) FRIEND

Somehow it was smuggled ashore and sent on its way. Postmarked “New York, August 1,” it must have reached the President’s House two or three days later. Here, the harried Madison (or some equally harried aide) bucked it to Winder … who filed it. Once again, as so often happens, a vital piece of intelligence was lost. Once again the truth was passed over—perhaps because the circumstances seemed so preposterous—while a dozen false leads were eagerly snapped up, because they seemed so plausible. And once again, what might have been anticipated came as a total surprise.

And surprise it was—not just in Washington but throughout the country. Even after word spread of the British landings, the capital seemed perfectly safe. “We have full confidence in the officer to whom, for six weeks past, the protection of the District has been entrusted,” declared the New York Gazette and General Advertiser on August 23, the day before the roof fell in. “All look with confidence to the capacity and vigilance of the Commanding General,” echoed the Baltimore Federal Gazette and Daily Advertiser, “and we feel not a doubt that his foresight and activity will leave nothing undone that our security requires.”

The paper was no less confident the following morning. Unlike Winder, it correctly predicted that the British would head for the “pass” at Bladensburg, but there was nothing to fear. “Thermopylae” would be held, declared the editors, borrowing a not entirely happy analogy. “We of this town know our Leonidas well, and his fearless band.”

Even the experts agreed. Commodore Rodgers, hurrying down from Philadelphia with his seamen, paused at the Susquehanna to drop an encouraging line to his wife Minerva. Dated 4 P.M. on the 24th—the very moment of disaster—his letter reassured her: “Everybody in high spirits and no fears are entertained regarding the safety of Baltimore or Washington.”

Then the shattering truth, spreading slowly from town to town, carried along by the cumbersome mail stages that linked the country together. Philadelphia got its first inkling when the Baltimore Pilot Stage rumbled up to the City Hotel during the evening of the 25th. The first details were sketchy—just the army mauled at Bladensburg, Winder falling back. But at 11:00 P.M. an express rider pounded up with the dreadful news that Washington was lost.

By 1:00 A.M. on August 26 the Pilot Stage was rolling on north, now carrying proof sheets of the first Philadelphia extras. They were printed too soon to mention the capital’s fall, but the dispatcher managed to scribble on the wrapping, “The enemy has entered Washington after a severe battle.” Around 5:00 P.M., after the standard 16-hour journey, the stage arrived in New York, and by seven o’clock the whole city knew.

“DISASTROUS INTELLIGENCE,” proclaimed the Commercial Advertiser’s Extra, first on the street. “PAINFULLY IMPORTANT,” declared the more conservative Gazette and General Advertiser the following morning.

As sometimes happens, the national mood went from one extreme to the other. Complacency gave way to panic; confidence to despair. The wildest rumors swept the land: Barney dead … Georgetown wrapped in flames … Armstrong lynched at Frederick … Baltimore’s fashionable 5th Regiment wiped out … 15,000 British troops led by Lord Hill in person … the dreadful Admiral Cockburn driven in triumph through the capital “with a miss at his side.”

“I have just heard that Washington is in ashes,” Minerva Rodgers frantically wrote the Commodore on August 25, “I am bewildered and know not what to believe but am afraid to ask for news.” She was sure of only one thing: that the enemy was at hand and that Rodgers was in deadly peril: “Oh my husband! Dearest of men! All other evils seem light when compared to the danger which threatens your precious safety. When I think of the perils to which your courage will expose you, I am half-distracted, yet I would not have you different from what you are….”

Along with alarm went a sudden surge of anger, indignation and shame. “In what words shall we break the tidings to the ear?” asked the Richmond Enquirer on August 27. “The blush of shame, and of rage, tinges the cheek while we say that Washington has been in the hands of the enemy.” The Winchester, Virginia, Gazette didn’t bother with rhetorical questions as it tore into the administration leaders: “Poor, contemptible, pitiful, dastardly wretches! Their heads would be but a poor price for the degradation into which they have plunged our bleeding country.” Philadelphia’s United States Gazette demanded these men resign, and failing that, “they must be constitutionally impeached and driven with scorn and execration from the seats which they have dishonored and polluted.”

The scorched walls of the Capitol itself blossomed with accusing graffiti: “John Armstrong is a traitor” … “Fruits of war without preparation” … “This is the city of Madison” … “George Washington founded this city after a seven years’ war with England—James Madison lost it after a two years’ war.”

It was hard to stand up against this sort of battering. The small, frail President seemed more shriveled than ever. Visiting him during these dark days, the lawyer-essayist William Wirt wrote his wife: “He looks shaken and woebegone. In short, he looked as if his heart was broken.”

One night four other visitors turned up. Led by Alexander C. Hanson, editor of the Georgetown Federal Republican and archfoe of the administration, they had come not to add to Madison’s miseries but to warn him of a plot on his life. Nothing definite was ever smoked out, but a corporal and six privates were hastily assigned to guard the President.

They were never needed. The first wave of anger soon gave way to new sympathy for the man. Steaming down the Hudson from Albany, Washington Irving felt it deeply when news reached the boat at Poughkeepsie that the capital had been taken. A fellow passenger snorted in derision and said he wondered what “Jimmie Madison” would say now.

“Sir, do you seize on such a disaster only for a sneer?” Irving stormed at the man. “Let me tell you, sir, it is not now a question about Jimmy Madison or Johnny Armstrong. The pride and honor of the nation are wounded. The country is insulted and disgraced by this barbarous success, and every loyal citizen would feel the ignominy and be earnest to avenge it.”

The press quickly caught the change in mood. “The spirit of the nation is roused,” proclaimed the influential Niles’ Weekly Register. “War is a new business to us, but we must ‘teach our fingers to fight.’—and Wellington’s invincibles shall be beaten by the sons of those who fought at Saratoga and Yorktown.”

Opposing factions drew together in the crisis. The very depths of the disgrace seemed to call for a new unity that would demonstrate to Britain in particular, and the world in general, that the American experiment could work. “Believe us, fellow citizens,” pleaded the anti-administration Albany Register, “This is no moment for crimination and recrimination, which necessarily follows…. Let one voice and one spirit animate us all—the voice of our bleeding country and the spirit of our immortal ancestors.”

Even Alexander C. Hanson’s venomous Federal Republican joined in the call for solidarity, showing that it was not just a passing impulse that prompted his concern for the President’s safety. “The fight will now be for our country, not for a party,” declared Hanson, who nevertheless couldn’t resist adding that old scores would be settled later: “When the enemy is expelled, we will then call to account, in the mode prescribed by the paramount law of the land, the traitors who may appear to be guilty….”

One after another the disaffected rallied to the cause. Former Governor Thomas McKean of Pennsylvania urged a huge rally in Philadelphia to stop looking at the past; look only to the present and the future. In Cincinnati General William Henry Harrison forgot his differences with the administration and appealed to the governors of Ohio and Kentucky to send help at once. New York’s Rufus King, darling of the Federalists, called for all-out defense. When the question of money arose, King had a ready answer: “Let a loan be immediately opened. I will subscribe to the amount of my whole fortune.”

Even New England, hotbed of the antiwar movement, rose to the occasion. Governor Martin Chittenden of Vermont, who in 1813 had tried to keep his militia from serving outside the state, declared that the war had assumed a whole new character: “The time has now arrived when all degrading party distinctions and animosities, however we may have differed respecting the policy of declaring, or the mode of prosecuting the war, ought to be laid aside; that every heart may be stimulated and every arm nerved for the protection of our common country, our liberty, our altars, and our firesides.”

The people needed no prompting. They were already on the way. “Our county is all alive and will be down soon to the relief of our friends,” Colonel Sam Ringgold of Boonsborough, Maryland, wrote General Winder on August 26. “Sir, believe me, this country is all on fire and raising [troops] of their own free will and at their own expense,” Captain John Sterrett, the U.S. Army barrack master at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, wrote the War Department on the 30th. He added that he had turned the barracks over to the quartermaster and was coming himself.

“To stand with folded arms and look on the scene as a mere spectator is not to be borne,” Colonel J. A. Coles wrote James Monroe. Coles was awaiting court-martial as a result of the defeat at Chrysler’s Farm on the Canadian front, but now he begged Monroe to suspend his arrest and let him serve at least as a private.

Corporal Robert Thompson was only a disabled veteran with an honorable discharge, but the loss of the nation’s capital was too much for him too. “It makes me again resort to arms,” he wrote the government on September 3, “though I feel rather unable, owing to my wound, which plagues me in damp weather, but in spite of it, I’ll go.”

They came from near and far. At Frederick, Maryland, Captain John Brengle’s company of 84 men was raised August 25 on the impulse of the moment; in four hours they were on their way to Washington. In the remote Richland District of South Carolina the citizens raised 100 men and $3,000 to buy their supplies. “Conflagration and rapine will never bow the spirit of the American people,” the Richland Citizens’ Committee wrote the War Department. “Our enemy, we hope, will find that they have miscalculated our resources and our spirit.” They added that they did need a bugle.

In the big coastal cities the outpouring was enormous. On August 30 alone the Philadelphia General Advertiser ran 23 notices calling on various groups to report for duty, or announcing the formation of new volunteer units. The paper’s advertisements reflected a new concern for military affairs: the Washington Rifle Co. needed a bugler … “Gentlemen wishing uniforms embroidered in a prompt and neat manner will please apply to No. 2 Carter’s Alley” … John Gathen offered the latest in pompoms, noting that “pom-poms have been adopted by the United States in place of feathers.” A strong editorial argued the value of the pike as a military weapon; it was, the writer assured any skeptics, known as “the queen of arms.”

While Philadelphia’s raw recruits explored the art of war, thousands of their fellow citizens began digging entrenchments. They came from every walk of life—62 carpenters … 200 printers … 30 teachers … 140 crewmen from the frigate Wasp … 400 watchmakers, silversmiths and jewelers … some 15,000 men altogether.

Early every morning the groups working that day got their assignments and began to dig. At 10:00 A.M. the drum beat for grog. At noon it beat for dinner and more grog. At 3:00 P.M., and again at 5:00, there were breaks for still more grog. At 6:00 the drum finally beat retreat, at which point the General Orders suggested tactfully: “For the honor of the cause in which we are engaged in, freemen to live or die, it is hoped that every man will retire sober.”

The women did their bit too. Meeting on August 30, 100 of Philadelphia’s fairest turned out 120 riflemen’s uniforms in two days. At nearby Frankford the young ladies sewed a standard of “elegant colors” for the local artillery company. Miss Mary Dover made the presentation, promising a blushing Captain Thomas Duffield that the girls would “fly to meet you on your return.”

The scene was repeated up and down the seaboard. In these hectic days it almost seemed as if John Jacob Astor were the only person still carrying on a normal life. The rich New Yorker hoped to operate the next flag-of-truce vessel for Europe—highly desirable since the ship would enjoy free passage through the British blockade. On August 22, he wrote Monroe asking the government’s approval, but if the letter reached Washington at all, it went up in the flames that engulfed the State Department. Naturally there was no reply. August 27, Astor fired off another letter. Although by now he well knew of the capital’s fate, he was so absorbed in his project that he ignored recent events completely. Not a word of worry or regret; just a touch of petulance:

Perhaps my letter of the 22nd has not been received or you had not time to write. I hope no other arrangement has been made and that the ship which I have prepared will receive the Flag, as otherwise it will expose me to unpleasant circumstances, if not some discredit, as I have long since advertised her.

He urged Monroe to write; sent along his own man to wait for an answer; and threw in a paragraph that couldn’t help but catch the eye of a hard-pressed administration leader: “Myself with a number of other wealthy citizens are much engaged to form a system for a national bank to relieve the country from its present pressure as respects finance.”

Perhaps that was what did it. The economy was in chaos … recent events would make it harder than ever to raise money … Astor’s help could be a lifesaver. Monroe hastily scribbled a note to the State Department clerk: “Mr. Graham to inform Mr. Astor that his vessel will be employed, but owing to present state of affairs, must be delay.”

There was so much to do. Washington was deluged these days not only with offers of assistance but with demands of every sort. New York’s Robert Fulton was in town lobbying for funds to finish his “floating steam battery”—said to be the answer to that city’s defenses. Major General Barker of the Virginia Militia was demanding reinforcements, additional artillery, better equipage and more provisions for his state’s northern counties. Governor Joseph Alston of South Carolina was demanding better protection for Charleston. The Philadelphia Committee of Safety seemed to want the moon—even the transfer of General George Izard’s army from the Great Lakes to the Schuylkill.

Monroe and William Jones desperately fenced them off. Fulton got $40,000, but most of the demands were out of the question. The government, the harassed Secretaries explained, couldn’t be everywhere at once. The limited forces available had to be used where the danger was greatest.

That was just the trouble. Every local official thought his danger was the greatest. By September 6 Cochrane was in the Bay again, and Gordon had passed the last obstacle down the Potomac. Soon they would be reunited—ready to strike somewhere—yet the available intelligence was hopelessly contradictory.

Baltimore or Norfolk would be next, declared some people at Benedict who had overheard the British talking. “Nothing was said about going to Baltimore, but a great deal about taking New London or Long Island and making winter quarters there,” reported Major William Barney after interrogating three British deserters at Annapolis. “There cannot be a doubt that Richmond will be their next object,” announced the Virginia Patriot, citing sources “which may be depended on.”

“As soon as the army is all reembarked, I mean to proceed to the northward and try to surprise Rhode Island,” Admiral Cochrane privately wrote Lord Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty, on September 3, as the British fleet worked its way back down the Patuxent. Once there, he went on to explain, he would land and rest the troops till the end of October. Then, bolstered by reinforcements from England, he would move southward again, take Baltimore, and head on down the coast. “As the season advances, I propose going to the Carolinas, Georgia, etc., and ending at New Orleans, which I have not a doubt of being able to subdue and thereby hold the key to the Mississippi.”

The plan had much to recommend it. A shift to Rhode Island would divert the Americans. Their newspapers were already filled with rumors of Lord Hill coming over with a huge army to attack New York. This would look like the opening move. It would draw thousands of troops from the Baltimore area and, just as important, keep Madison from reinforcing his army in Canada.

Above all, it would get Cochrane’s men out of the Chesapeake during what was known as “the sickly season.” Nothing weighed more on British minds. In August 1813 Admiral Warren’s force had been swept by a mysterious fever that struck down 500 of his 2,000 men. Vaguely attributed to noxious vapors rising from the swamps, it was thought to be a seasonal phenomenon that the Americans could perhaps survive but certainly not a civilized people. “The sickly season here is about at its height,” the Fleet Captain Edward Codrington wrote his wife, “and from the uncommonly cadaverous appearance of the natives who are in health, the country with all its beauty of scenery is not fit for the habitation of social man.”

So they would head north for a while, but they would be back, and then it would be Baltimore’s turn. This lively, brawling seaport up the Bay sat at the top of the list of British hates. It had supplied 126 of the privateers that ravaged British commerce. It was generally considered a “nest of pirates.” It was, in Admiral Cochrane’s mind, “the most democratic town and I believe the richest in the union.”

A special fate awaited this most special target. There might be some excuse for respecting private property in Washington, but not here. “Baltimore may be destroyed or laid under, a severe contribution,” Cochrane wrote Earl Bathurst on August 28. Writing Melville six days later, he no longer talked of ransom; instead, he was worried about a delicate problem that might spoil his plans for total destruction:

As this town ought to be laid in ashes, if the same opinion holds with H. Maj.’s Ministers, some hint ought to be given to Gen’l Ross, as he does not seem inclined to visit the sins committed upon H. Maj.’s Canadian subjects upon the inhabitants of this state.

It was not that Ross lacked zeal, Cochrane hastened to add. It was just that he was soft. “When he is better acquainted with the American character,” the Admiral observed, trotting out his favorite simile, “he will possibly see as I do that like Spaniels they must be treated with great severity before you even make them tractable.”

Admiral Cockburn thought Ross was soft too, but with that went pliability, and this could be turned to advantage. Time and again on the road to Washington he had won the General over to his own schemes; now he went to work again. Like everybody else, Cockburn wanted to get at Baltimore; but unlike Cochrane, he wanted to do it right away—while the British were still in the Chesapeake … while the Americans were still demoralized … before they had time to organize the city’s defenses, build fortifications, bring in new troops, arouse the nation. As for the “sickly season,” the dangers were vastly exaggerated. He had been here last year, and he knew.

Ross leaned the other way. For Cockburn it wasn’t as easy as those days when they were in the field together. Now he was back on the Albion; while the General was on the Tonnant, where Cochrane could see him all the time.

But Cockburn did have a powerful ally on the Tonnant. This was Lieutenant George de Lacy Evans, Ross’s Deputy Quartermaster General. Although nominally a junior staff officer, Evans had the General’s ear. He had always sided with Cockburn in those discussions on the road to Washington. It was no different this time.

Ross still leaned the other way. But he was doubtful enough to ask his Deputy Adjutant, Captain Harry Smith, for his opinion. Smith was all against an attack just now: rumors planted by the British themselves had already drawn too many American troops to Baltimore; a brilliant stroke like the capture of Washington could rarely be repeated; the approach up the Patapsco River could be easily blocked; too many of the men had dysentery; and most important of all, there was so little to gain and so much to lose. Washington was a tour de force; Baltimore would be at best an anticlimax and could be a disaster.

“I agree with you,” Ross nodded. “Such is my decided opinion.”

Smith had been appointed to carry Ross’s dispatches back to England, and with this in mind, he now asked if he could tell Lord Bathurst that there would be no immediate attack on Baltimore. Yes, said the General, he certainly could.

On September 3 Smith left. As he headed for the gangway to catch the launch to the frigate Iphigenia, the General walked beside him. Reaching the rail, they shook hands, and on an impulse Smith asked once again, “May I assure Lord Bathurst you will not attempt Baltimore?”

“You may,” said Ross, not a doubt in his voice.

Certainly it looked that way. On September 4-5 a flurry of orders went out to the various commanders, dispersing the fleet on new assignments: Admiral Malcolm to take most of the warships and all the transports to a point south of Block Island … Captain Sir Thomas Hardy to take 13 of the ships and relieve Admiral Cockburn in the Chesapeake … Cockburn to take the Albion, now loaded with prize tobacco, dispose of it in Bermuda, and rejoin Cochrane at a secret rendezvous apparently south of Block Island.

As the ships started on their separate ways, Admiral Cochrane sent a hearty “well done” to all hands:

The Commander-in-Chief cannot permit the fleet to separate without congratulating the Flag Officers, Captains, Commanders, officers, seamen, and marines, upon the brilliant success which has attended the combined exertions of the Army and Navy employed within the Chesapeake….

And so, with the felicitations of their grateful chief, the captors of Washington moved down the Bay convinced that their mission, for the present anyhow, was completed in these waters.