Three

AN EDUCATION

When I was six years old, my dad’s job changed and we moved from Garches to the neighboring town of Meudon, where we were given an elegant house that bordered the town hall on one side and an orphanage on the other. Meudon is an interesting little city presided over by a royal chateau once favored by the son of Louis XIV. The artist Auguste Rodin came from Meudon, as did Rabelais, the sixteenth-century satirist who wrote a line I have always been fond of: “A child is a fire to be lit, not a vase to be filled.” After a few years, my dad changed jobs again and my parents bought a condo in Meudon with wonderful views toward Paris. Since starting school, I had become very busy. I played handball, eventually becoming the captain of my school team. I competed in judo, soccer, and tennis, as well as other sports. I was good at sprints, mainly the 100 and 200 meters, and discovered that long-distance running wasn’t for me. The fast and the furious suited me better. I realized that I was very competitive and I liked to win.

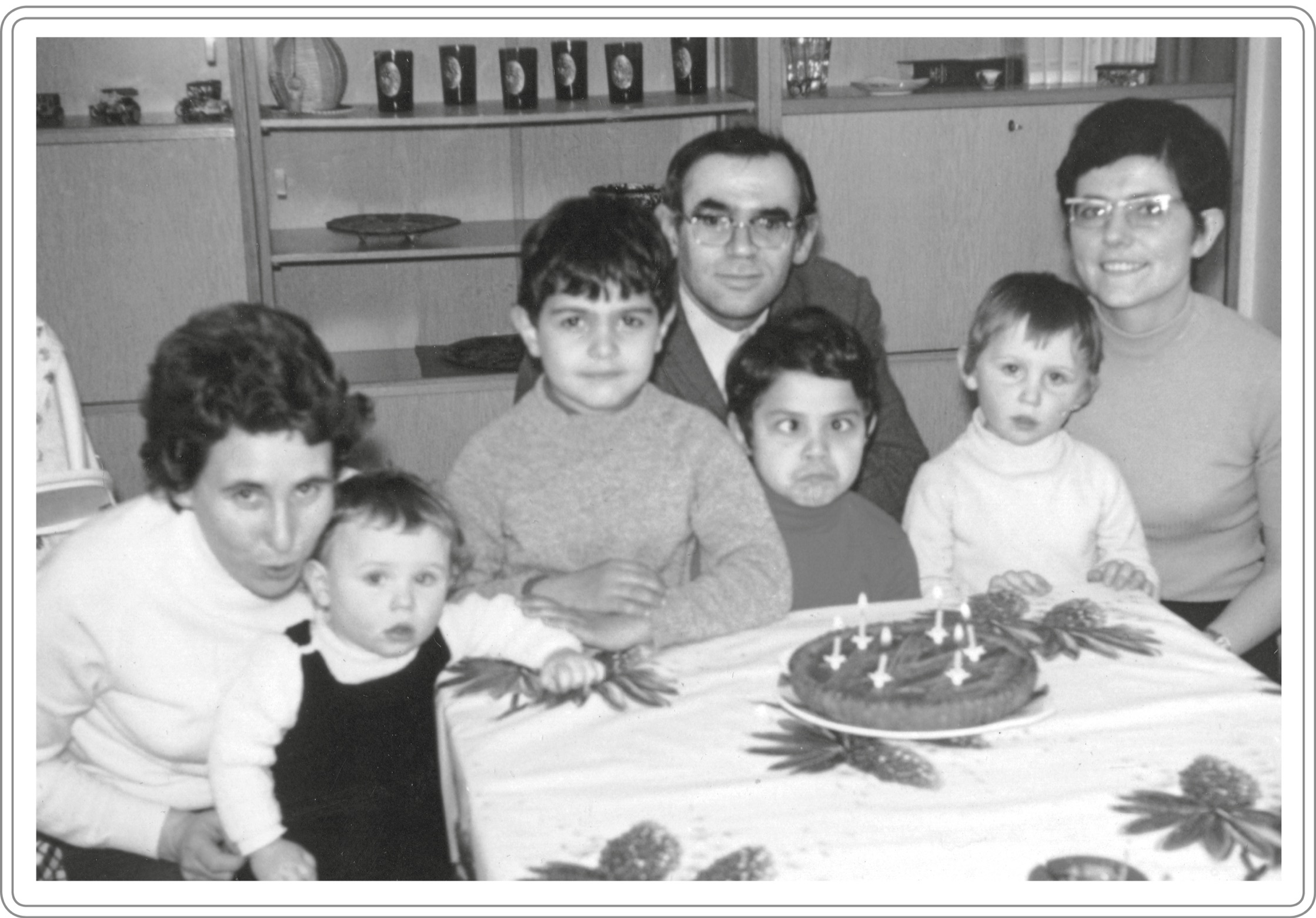

June 1970, five years old.

The only athletic pursuit to which I didn’t take was ballet. Oh god, I tried. My parents sent me to classes from the age of about six and I kept going for almost three years. It was partly that I had very short hair and glasses and felt out of place among the other ballerinas. But even without that, the dance didn’t interest me. I could enjoy the music, but ballet was way too proper for me, and instead of doing the steps I would mess around until the teacher grew furious. Eventually, I dropped out.

By and large I was a well-behaved kid. I wasn’t the best student, but I had a good memory and was diligent in class, partly out of a natural desire to please, and partly out of calculation: the better my grades and behavior, the greater license I had to do what I wanted to do. The only time I got into any real trouble was when I was protecting my brother. Jean-Christophe is older than me, but of the two of us, I have always been the more assertive. He is very kind, generous, and loving, and much softer than I am. If I ever saw him being bullied at school I would jump right in and start fighting. “You can’t do that,” the principal would say after I’d been sent to his office. But when I got home, my dad was usually on my side.

One day, out of the blue, my mother started bleeding. When she went to the doctor, she was told she had an internal abscess and would have to be admitted to the hospital for treatment. She would end up staying for almost three weeks, and after being discharged was incapacitated at home for a further two months. My father, brother, and I had to fend for ourselves.

Of my parents, my mother might have been the quieter of the two, but she was the engine of our house. If I idolized my dad as someone who knew more than anyone else in the world, I recognized my mother as the one who got things done. She was no-nonsense, practical, efficient, and kind, and we all knew she held everything together. When she got sick, we were completely at sea.

The face of a serious chef.

Part of the problem was my dad. He was interested in food and had a good palate, but I have to be honest: he was a terrible cook. He would do vaguely culinary things like bring a whole leg of Jambon de Bayonne back from holiday in Spain and hang it in our basement to cure, disappearing before dinner every evening and returning a moment later with a plate piled with slices of ham. But when it came to actually cooking, he was hopeless. In the days after my mother was admitted to hospital, he struggled to feed my brother and me. One night, he served us raw beets with the skin still on.

For years I had been watching my mother in the kitchen, just as she had learned to cook at her mother’s side. I knew how to shop at the market—that the main thing was to keep things simple and focus on good, fresh ingredients. And I knew what my dad liked. And so, at nine years old, I took charge of the kitchen. One afternoon I got back from school and tentatively started devising some menus. A little soup; some vegetables and grilled meats; a little salad and a cheese platter with charcuterie. It didn’t need to be much—my dad and my brother’s needs were very plain—but it had to be better than a TV dinner. At the end of the night, before he went to bed, I would make my dad a pot of chamomile tea.

It was a difficult time. My dad was working very hard and would often come home right before dinner, eat, and be wiped out for the rest of the evening. He was, I knew, tremendously worried about my mother, and going to visit her in the hospital was stressful. At home, although the rest of the family rallied round and gave us support, the house felt small and dark in my mother’s absence. The most painful thing, however, wasn’t worrying for myself, or even missing my maman, but watching my parents’ worry for each other. There is nothing more unsettling to a young child than the collapse of parental infallibility.

I asked my mother about this period recently and the first thing she said was, “Yes, that’s when you took over the household so well.” Perhaps in some families, a nine-year-old cooking for the family would have been considered odd. What I did in the kitchen during those weeks barely qualified as cooking—it was assembly more than anything else—but through a trying time, making food for my family kept me going. It felt to me like the simplest and most tangible way to show care, in a language I, at the age of nine, couldn’t have articulated any other way. When after three months my mother returned to good health and the kitchen, I felt tremendous relief and also a sense of accomplishment. More than that, I felt something I had never felt so clearly before: purpose.

As I got older, I started to travel more widely. As a family, we went on holiday to Spain and Martinique. I loved the Basque country, the fatty taste of the ham we ate there, the sense of Spanish history. We went on hiking trails through the Pyrenees, wrapped up against the cold, where I would take great gulps of clean mountain air and thrill to how different it was from the sea. Back at Locronon, we spent long days on the beach, returning to the house where my dad would retire to his atelier, a small workshop in the garden where he did all his painting. My dad’s day job was challenging and interesting, but I sometimes think he truly came into himself only when he was at his easel. He had no formal training as an artist, but he was good and his paintings were very personal. One day, he painted a canvas with beautiful white flowers. He said that as he’d worked on it he’d been thinking of me.

Four years old, hiking in Lourdes.

Some of the trips I went on were better than others. One summer, my brother and I were sent to La Colonie de Vacances, a kind of summer camp in the Vendée on the west coast of France. After a week, I wanted to get out. I didn’t like the director of the place, although I couldn’t put my finger on why. I have always trusted my instincts, however, and when I don’t like something, I tend to speak up. When my parents came to visit, I told them there was something about this guy that gave me the creeps. That’s all it took. They pulled my brother and me out and drove us straight home.

Another summer, when I was eleven, my brother and I went on a student exchange trip with our school, to a school in the south of England. The school was in Farnborough, Hampshire, and each of us was put up by a different host family. A few days into the trip, one of my brother’s friends was caught stealing from his hosts, and although Jean-Christophe was not implicated, I was informed by the teacher that, because of his association with the thief, he was to be sent home, too.

This seemed to me a monstrous injustice. The next day, when the perpetrator and my brother were due at the school early, I was waiting for them in the courtyard at 7:00 a.m. Without thinking, I ran up to the boy who had caused all the trouble and started to beat him up. The teachers could hardly get me off him. Eventually, Mme Gremier, our English teacher, pulled me off the boy, and I was taken to the head teacher’s office. When they got my dad on the phone, I could barely get the words out. “Dad, Jean-Christophe—” I said.

“I know,” he said. “I know the story. Are you okay?”

“Yes,” I said. “Are you mad at me?”

“No,” he said. My dad always approved when I stood up for my brother. “You did the right thing.”

Freezing cold water at the beach in Brittany.

Growing up, overall, I was happy at home. I was happy at school. I loved my parents and was secure and had friends. I was doing well in every area of my life. And yet, as I entered my teens, I started to see myself as someone who didn’t really fit in.

It is hard to pin down where a feeling of not belonging originates when it doesn’t correspond to the obvious things. It’s true that I had some unresolved feelings about my adoption, and how I couldn’t find a reflection of myself, anywhere. I was always looking at faces, interested in the physical traits that they had and wondering if I might have them, too. At the same time, if anyone ever tried to claim me, I would shrink in horror. Strangers would occasionally stop me in the store to speak Arabic, assuming I was of North African or Middle Eastern descent, and I would be filled with indignation. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be those ethnicities, but rather that it felt like a negation of my life. “I’m not you!” I would rage in my head, in that moment claiming my parents and my right to be from Brittany.

And, as I approached my teens, it’s also possible that my balance was upset as my sexuality started to come into question. I had always looked slightly different than the other girls, favoring short, boyish haircuts, and as early adolescence drew closer, my tastes started to feel at odds with those of the people around me.

In the late 1970s, few people in French public life were openly gay; it wasn’t spoken of on TV or referred to in newspapers, except in the context of a sex scandal. And while my parents were liberal in some ways, our social milieu was overwhelmingly straight, white, and Catholic. I had no idea that a wife might be in my future; all I had was the vague sense that my style, interests, and enthusiasms weren’t quite right for a girl my age. I also had a feeling that it was something my parents wouldn’t understand.

There were other things that set me apart, too. Looking back, it seems to me that if I felt different from my peers, it wasn’t only because I didn’t know who my birth parents were or because I had a crush on Olivia Newton-John. It was also because I had unusual interests for someone of my age. I preferred talking to adults rather than other children. In spite of my friends, I was a bit of a loner. I sometimes looked at the other kids—particularly those who boasted about going on ski trips or other expensive holidays—and thought they didn’t think for themselves. I couldn’t find myself in those groups, where the girls in particular always seemed a bit vacant. And I was a political junkie, which no other eleven-year-old I knew was.

Every night at the dinner table, my dad talked to me about politics. He knew I was interested in political history and would tell me about the figures he admired, such as Simone Veil, the French health minister and survivor of Auschwitz who in the mid-1970s passed the first abortion laws in France. He told me about Simone de Beauvoir and sketched an outline for me of French feminist history. He talked about Coco Chanel, who’d once had a house not far from our old place in Garches.

When we talked, it was never like he was trying to impose his views on me. The point of our conversations was to wake up my curiosity, and after he talked, it was my turn. I sometimes think there is no greater gift a parent can give to their child than to listen—to really listen.

After a few years of absorbing my dad’s talk about politics, I found it wasn’t enough for me to simply listen. I was ravenous for more information about the world and I wanted to get out there and see it. My dad had some good friends in Warsaw whom he had met through his political connections, and when I was twelve, I did something truly eccentric: I begged my parents to let me travel to see them.

It is extraordinary, looking back, that I was permitted to take this trip. This was in the late 1970s, when Poland was still under Communist rule and often on the TV news owing to its cycles of unrest and authoritarian crackdown. Generally in life I like to be in the middle, where I can get ideas from both sides. But political extremism fascinates me and I was obsessed with learning what life was like behind the crumbling Iron Curtain. Please, please, please, I asked my dad, can I go to Warsaw? Astonishingly, after enough pestering, he said yes, as long as my brother went with me. And so a twelve-year-old and a fourteen-year-old boarded a train in Paris bound for Communist Poland.

I don’t know what I expected. And my mind still boggles at the idea that my dream vacation, at that age, was to spend almost twenty-four hours on a train while it chugged toward a totalitarian state. At the time, however, I just threw myself into it and let the adventure unfold. The train was a sleeper. My brother took the bottom bunk and I took the top. That first afternoon, we sat playing cards and looking through the window as the flat, European farmland sped by, before retiring to our bunks for the night. The idea of sleeping on a train was impossibly exciting.

Very early the next morning, we were woken by sharp noises. The train had reached the border between West and East Germany, and as I pulled back the curtains, I saw a line of soldiers with rifles and German shepherds. They were shouting as they boarded the train: “Passports! Passports! Passports!” My brother and I fumbled with our paperwork, hearts pounding, but nobody raised the slightest objection to the passage of two unaccompanied minors. Eventually, the train resumed its journey.

I found the experience of seeing the world anew, stripped of every certainty, completely and utterly mind-blowing. Our dad’s friend was there to meet us on the platform in Warsaw, and the first thing I asked him about was the wagons we had seen from the train with USSR stenciled on the side. He explained that in spite of severe food shortages in Poland, the country was obliged to send a great deal of its farms’ produce to Russia. “How do you guys live?” I asked, and when we returned to his house, he opened a trap door and showed his family’s stash of black market food. It was like something out of a movie.

It was also an early lesson in something I would come to better understand years later: food is politics. When a government wants to suppress its people, the first thing it does is go after the food—just look at the famine in France before the Revolution. If you control the food, you control the people, and this can be as true of Western democracies as of repressive regimes. Industrial farming and the might of the sugar and fast-food lobbies don’t exert the same control as a totalitarian government, but they are still hugely powerful. Nutrition informs behavior, and a badly nourished populace, like a badly educated one, is compromised in its political will.

After that first trip to Warsaw, I revisited Poland many times, right up to the 1989 elections, when the Communist order started to crumble and Lech Walesa and his Solidarity movement entered the government. By then, I had totally fallen in love with the place and the Polish people. One of my first boyfriends was Polish. I went to a Polish wedding, where the food was terrible. Like German food, Polish food is all sausage and potato, and not my kind of thing at all. But I loved the country and went back every time I had the chance.

I am still amazed by the bravado of that first trip. If Poland fascinated me, it was because of something I wouldn’t have been able to articulate at the time, but that I can now identify as an interest in the dynamics of freedom. On that student exchange trip to England, before my brother was sent home, some English boys playing soccer in the street invited me to join them. I was completely flat-chested, and with my short, dark hair it was obvious to me that they thought I was a boy. For a moment, I hesitated, wondering if I should point out their error. Then I ripped off my shirt, ran out into the street, and for the space of an hour, ran around playing soccer in the sun, as free as anything in the world, as free as the boys.