Ten

PAPA CRENN

There is a photo of my dad as a young man, taken in Marseilles shortly after the war. He is standing alongside Charles de Gaulle at the First Congress of the RPF—the Rassemblement du Peuple Français—the political party de Gaulle founded in 1947 and that for a while drew my father’s support. Later, my dad would disagree with much of what de Gaulle stood for politically—he was far too right wing for my dad’s politics—and would even participate in the demonstrations against him in Paris in 1968. But he always revered him for his bravery during the war and I think they recognized that trait in each other. When, after the war, de Gaulle rewarded heroes of the Resistance with the title Compagnons de la Liberation, one of them was my dad.

I often think of that photo. A copy of it is held, along with forty-odd other photos of him, in the archives of the Resistance in France. It’s all there in black and white: records of my dad’s sabotage operations when he was still a teenager, his military training with the American Ninth Air Force and subsequent service as a paratrooper, his contribution to the rebuilding efforts after the war. When he told us the stories, his tone was matter-of-fact and the moral unchanging. Heroism, he said, wasn’t a question of movie-like daring. More often than not, it was simply a case of going on.

It was my mother who rang me to tell me that after a period of feeling unwell, my dad had been rediagnosed with prostate cancer. The first diagnosis had been made three years earlier, and now it had come back and spread to his bones. I was gearing up for the move to Indonesia, and my mother’s instinct, I realized later, was to downplay things to protect me from worry. I got my dad on the phone, and he also reassured me there was no immediate emergency. He sounded the same as he always had. He and I even talked about death, as we had talked about everything all of my life. He said he wasn’t afraid.

I wasn’t afraid, either. My dad was invincible, everyone knew that. And the fact that he was able to talk about death somehow made the possibility of it seem more remote. As I managed the difficulties of my job in Jakarta and then set about establishing a new life in LA, I had no real sense of what was happening. But throughout 1998 and into the beginning of 1999, my dad’s health steeply declined.

It’s a natural parental instinct to protect one’s children from harm, and my mother thought she was doing the right thing. The disease was progressing, but I had just started my new job at the Manhattan Country Club, and in her eyes I was horrendously busy and didn’t need the added worry of wondering whether I should be bolting back to France. But I wasn’t a child; I was a woman in my thirties and I needed the information. It was later that year, on a hot summer day, that I spoke to my dad on the phone without fully realizing we were so close to the end. He told me that he loved me.

My two men, 1998.

The next time I spoke to anyone from my family, it was my brother, calling with the news. I couldn’t understand what he was saying. I simply couldn’t process the information. My father was dead, he said, but how could that be? Outside my window, everything looked just the same. But here was this person on the line telling me the entire world had been turned on its head.

I remember nothing beyond the numbness of that day, and in the days that followed, my mind circled around irrelevant details. It was July and, absurdly, what I remember about flying from LA to Paris is that on such short notice the flights were hideously expensive. I changed planes in Paris, taking a small regional flight to Brest, in Brittany, where my brother picked me up. I was wearing summery shorts and a shirt and my brother took one look at me and said you need to change. “Change for what?” I said. He stared at me. “There are people at the house,” he replied.

Traffic. I remember that. So many cars parked outside. They went all the way up the street. I entered the house, hugged my maman and other members of the family, then walked slowly up the stairs. In my parents’ bedroom my dad was laid out on the bed. I stared at his face, trying to catch a moment of movement. The Catholics believe in the afterlife and I found myself thinking, So where is he now? I wondered if I needed to start believing in God, just so I could believe that my dad wasn’t gone. As I stared at his face, the size of my want was so huge that for a split second I was convinced I saw him smile. I lay down next to him and started to cry.

My dad was seventy-four when he died and I was not a child. I had had him for over thirty years, much longer than many people have their parents. And he and I had had the best possible relationship. There was nothing I wished I had told him, no conversations un-had, no I love you’s unsaid. But at the end of the day, none of that matters. When you lose someone you love to the extent I loved my dad, no amount of time will ever be enough. I still wanted more.

Eventually, after lying next to my dad for I don’t know how long, I forced myself up and returned downstairs. My maman was hosting the mourners, organizing and holding everyone together. She was so strong and I wanted to be strong, too, but at that point I felt completely obliterated. I hadn’t eaten since receiving the phone call from my brother almost forty-eight hours earlier. That afternoon, at the funeral, I fainted during the church service.

It would be many, many years before I could process my father’s death. In the meantime I worked like crazy.

This sounds like a textbook case of denial, but it wasn’t quite that. People in denial live their lives in a clenched, troubled way. But while I worked very hard after my dad’s death, setting up the Country Club kitchen and settling into life in LA, I let myself feel the pain of his absence. It was incomprehensible to me, but I still knew he was gone. It was coming to terms with it that took so much time.

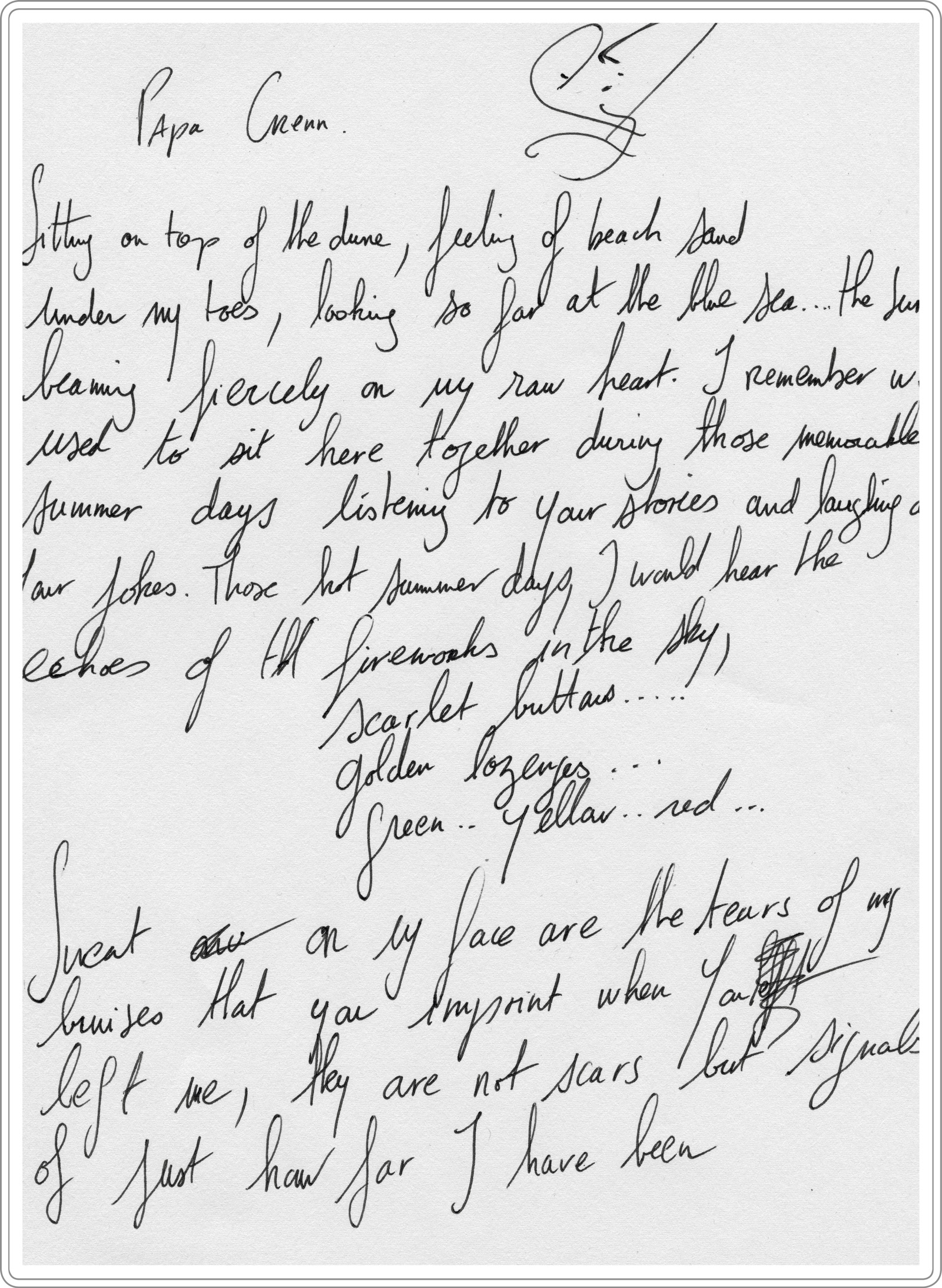

When I create something, I oscillate between celebrating the transitory nature of time and trying to figure out how to hold on to it—how to make something fleeting so forceful it stays in one’s mind. Mostly I do this through food, but occasionally I try other types of expression. Over time, I would find larger ways to pay tribute to my dad, culminating in the opening of a restaurant that bore his name. Immediately after his death, however, the only way I could find to express my love for him was to write it in a poem.

Papa Crenn,

Sitting on top of the dune, feeling of beach sand under my toes,

Looking so far at the blue sea . . . the sun beaming fiercely on my

Raw heart. I remember we used to sit here together during those

Memorable summer days, listening to your stories and laughing at

Your jokes. Those hot summer days I would hear the echoes of

The fireworks in the sky,

Scarlet buttons . . .

Golden lozenges . . .

Green . . . yellow . . . red . . .

Sweat on my face are the tears of my bruises that you imprint

When you left me. They are not scars but signals of just how far I

Have been and how far I will go . . . with you at my side.

I miss you.

Your daughter

A copy of this poem hangs on the wall of the dining room at Atelier Crenn. I pass it every time I walk from the kitchen to the bar. My life changed when my dad died, and one small effect that persists is that whenever I see a number from France on my phone, my heart freezes. I will never forget the experience of my brother calling me that day. I’m painfully aware that, given my mother is eighty-five, at some point it will happen again.

My dad’s death made me reexamine my priorities. It reminded me of how lucky I’d been with my adoption and also made me reconsider what I wanted to do with that luck. I was thirty-four and had already spent years cooking food that didn’t really matter to me, and so in those years after my dad’s death, I became more resolved than ever that one day I would work for myself. It was my father, after all, who had taught me to always keep going.

My dad died in 1999. Almost twenty years later, I was the subject of a profile on the Netflix show Chef’s Table, during the course of which cameras followed me back to Locronon. I knocked on the door of my parents’ old house in the village, from which they had long since moved on. I walked along the shore where, as a child, I had spent so many happy hours with my family. And I walked around the graveyard where my dad is buried.

It was a strange pilgrimage, not least because I was being followed everywhere by cameras. But as an exercise, it was useful to look back on my life and realize, for what felt like the first time, that I was really at peace with his death. As I spoke of my dad to the interviewer, I understood that I had tried to absorb as much of his life into my own, and that after almost two decades without him, I had arrived at a place where I could let go and embrace who he was.

My dad loved soup. He loved jazz music. He loved his kids and he loved my maman. He taught me how to look at the world in a rare and courageous way and he enabled my adventures, even when they took me away from him. Every year, he loved to wake us at 4:00 a.m. on the first day of the summer and embark on the long drive to Brittany, the place he loved more than anywhere else.

Before I was born, my dad was the deputy mayor of a little village called Pont-Aven in Brittany. It would never have been heard of outside the region were it not for its illustrious association with artists. Paul Gauguin spent his summers in Pont-Aven in the 1880s and set up an artists’ colony called the Pont-Aven School, to which such postimpressionist luminaries as Émile Bernard and Armand Séguin belonged. It was here, as a young man, that my father first picked up a brush.

I have an image of him in my head, sitting still for hours in the atelier behind our summer house, intently focusing on his painting. “It was all a question of perspective,” he said, “in art as in life.” When he took me to a gallery, he would stand me before a particular painting and ask me what I felt. At first, I thought this was a test and I would stand in silence, staring at the painting while desperately searching for the right answer.

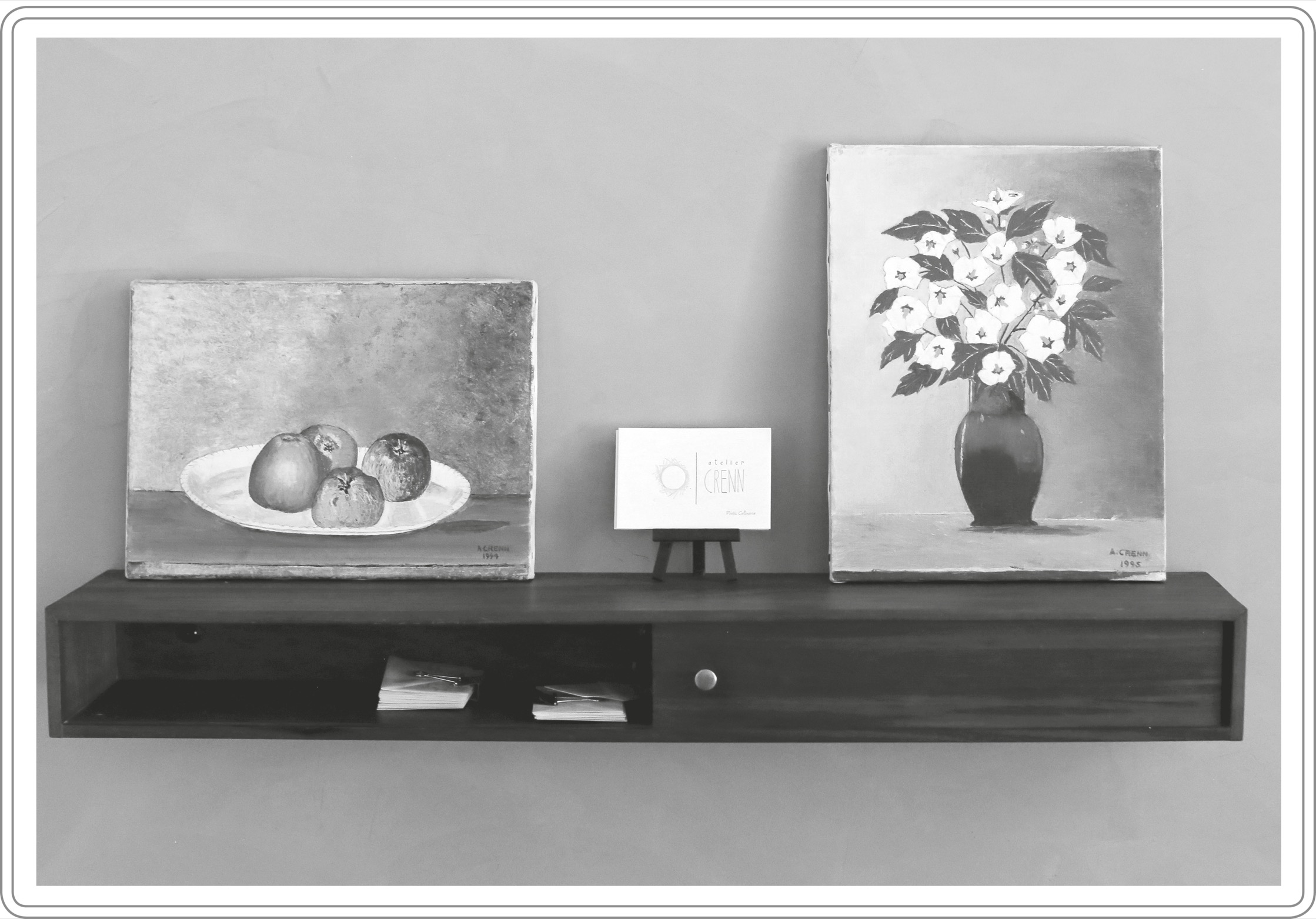

Art by Papa Crenn, hanging in Atelier Crenn’s dining room.

Eventually, my father told me there was no right answer. “I can’t tell you what to think about this painting,” he would say. “Because there’s no way for any two people to look at a painting the same way. All the artist can do is to create in a way in which we are made to feel something. What we feel, what we take away from it, is up to us.”

It was the same principle he applied to looking at the world; one could choose how one wanted to see it. For my father, the world was bountiful with gifts, and this is how I came to see it, too. On our annual trip to the coast, we would take long walks on the beach, looking at the birds and gulping sea air. Now and then, my dad would pause to point out some detail of the coastline, where the salt water had carved crescents into the rock. I followed his gaze, and what I saw, of course, had a different perspective. I saw not only what he saw—the sea and the sky—but I saw my dad, too.

Now, when I walk along the shoreline in San Francisco or return home to Brittany, all I have to do to find my dad is look out to sea or up at the sky. He died on the night of Bastille Day, the French national day, when fireworks light up the dark. That night, as my maman came into his room to check on him and kiss him goodnight, he told her, “Soon, there will be another firework in the sky.” When she looked in on him in the morning, he was gone.

For Papa Crenn.