Chapter 11

Developing a pain control program

Many people with chronic pain enjoy active and productive lives. If you aren’t among them, there’s no reason you can’t be. But it’s up to you to make it happen.

In this chapter and those that follow, we discuss various steps you can take to help lessen your pain and make it more manageable. There aren’t any quick fixes for chronic pain. And most often, you’re the key ingredient. If you want your life to improve, you need to lead the way.

You may not like the fact that you have chronic pain. No one does. But clinging to unrealistic hopes or expectations will only prolong your frustration and contribute to your feelings of helplessness. The first and most important step in controlling chronic pain is accepting the fact that you may always have pain. While some people are able to significantly reduce or eliminate their pain, for many people it will always be a part of their lives. Managing chronic pain is about learning how to keep your pain at a tolerable level so that you can enjoy life.

The remainder of this book focuses on specific lifestyle issues and pain management strategies that can help you better understand and manage your pain. The task ahead may seem daunting, but each small step you take in your new role as pain manager will boost your self-confidence and strengthen your faith in your abilities.

The choice is yours to make. You can continue to dwell on your discomfort, or you can do something about it.

Start with SMART goals

Goal setting is an important part of your pain control program and your first step in achieving pain relief. Goals help divert your attention from your pain, and they provide an opportunity to think about your lifestyle and what you can do to better manage your pain. Goals also give you something to strive for.

But goal setting isn’t as easy as it may sound. You simply can’t identify some things that you want to occur and expect them to happen. You’ll only be setting yourself up for disappointment.

In this chapter we talk about setting SMART goals — goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and timely. And in the remaining chapters, we give examples of how you can use the SMART formula in various aspects of your pain program.

Specific

Your goals should be clear and straightforward. State exactly what you want to achieve, how you’re going to do it and when you want to achieve it. To begin with, set goals that you can achieve within a week to a month. It’s easy to give up on goals that take too long to reach. You might even start off with a goal you can achieve the same day. If you have a big goal, break it down into a series of smaller weekly or daily goals. After you achieve one of the smaller goals, move on to the next.

Measurable

A goal doesn’t do you any good if there’s no way of telling whether you’ve achieved it. “I want to feel better” isn’t a good goal because it’s not specific and it’s difficult to measure. “I want to be able to work eight hours a day” is a better goal because it’s specific and measurable.

Attainable

Ask yourself whether the goal is within reasonable reach. Goals that are too far out of your reach you probably won’t commit to doing. For instance, completing a marathon may not be an achievable goal if you’ve never run before. However, short hikes around the neighborhood or completing a 5K run may be attainable.

Realistic

Is the goal realistic for you? The purpose of a goal is to shift your focus from your pain to your future. But you can’t ignore your limitations. Your goals need to be within your capabilities. If you’ve suffered a serious back injury, a goal of returning to work as a bricklayer may not be realistic. Instead, your goal might be to find a sales job in a related field. Or you might decide to go back to school for training in a new field.

Timely

Set a time frame for your goal. When do you want to achieve it? Next week? In six months? Putting an end date on your goal gives you a clear target to work toward. If you don’t set a completion date, there’s less reason to make a commitment.

• • • • •

How to be SMART

Here are examples of goals that follow the SMART formula:

Goal: Reduce my use of over-the-counter pain medications by 25 percent

When I want to achieve it: Two weeks

How I’m going to do it: Use other pain management strategies: exercise daily, pace myself at work and take frequent breaks, use relaxation techniques

How I’m going to measure it: Record in my journal daily the medication I took and how much

Goal: Exercise 20 minutes each day

When I want to achieve it: One week

How I’m going to do it: Stretch and do strengthening exercises five minutes in the morning, walk five minutes during my lunch hour, bicycle 10 minutes in the evening

How I’m going to measure it: Record in my journal when I exercised and for how long

• • • • •

What are your goals?

Think carefully about some short-term or long-term goals that you want to achieve. If you have some in mind, write them down now. Consider setting SMART goals for yourself in the following areas if you feel that they’re aspects of your life that could use some improvement:

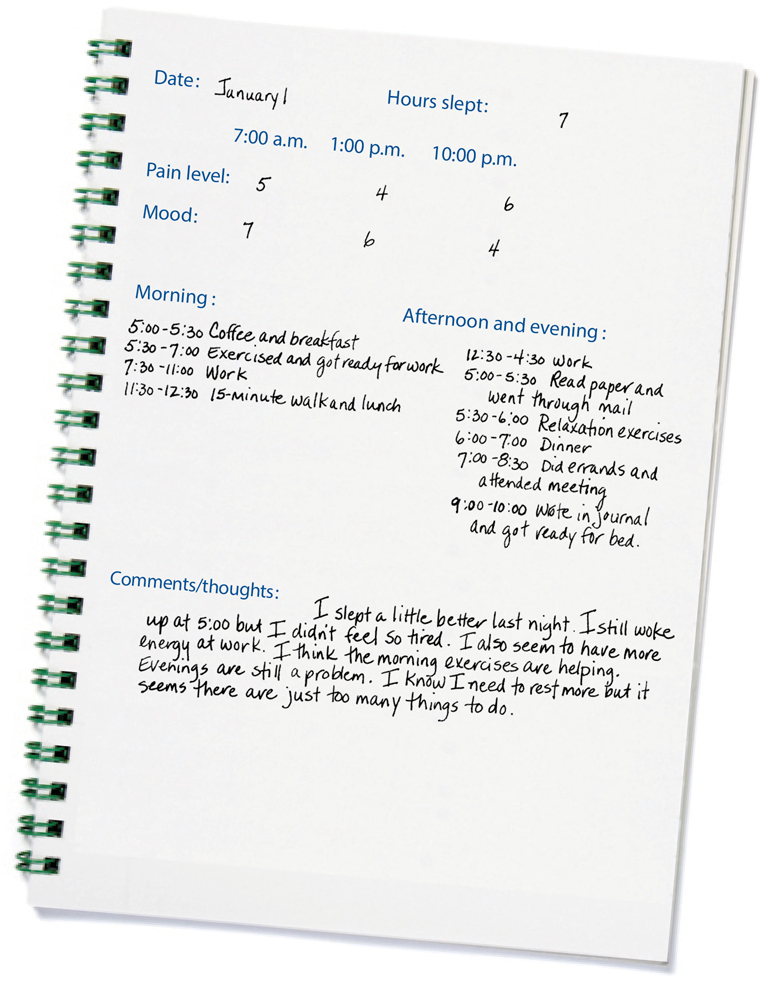

Put it in writing

As you begin to think about and set goals, something that you’ll find helpful in tracking your progress is a daily journal (see the “Sample journal”). In addition, a journal can help you determine those therapies or activities that seem to be helping you the most. As you work on your goals and you learn techniques to manage your pain, you should see a decrease in your pain level.

A journal can also open your eyes to aspects of your daily life that may be contributing to your pain. Many people think that their pain isn’t influenced by factors such as work, stress, sleep or physical activity. But after a few months of tracking their pain levels and their activities, they begin to notice some common patterns. And they begin to see things in their lives that they can modify to improve their pain.

In addition, a journal can be a great way to express your feelings about your pain or other things that are happening in your life. Writing your thoughts and feelings on paper helps you organize and sort through problems and emotions and get them off your chest, similar to the way you feel after a good heart-to-heart visit with a friend or family member.

Here are things to consider keeping track of in your journal. You don’t need to go into a lot of detail if you don’t want to. Your journal can be as basic or as detailed as you want it to be.

Pain level and activities

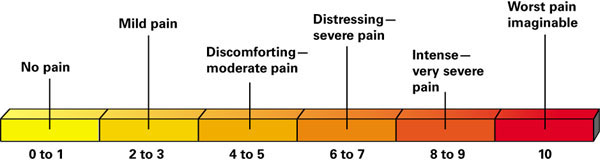

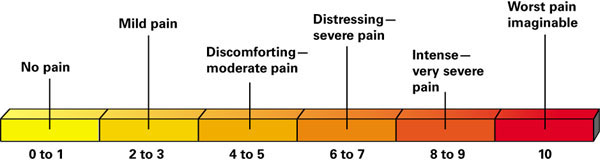

In your journal, begin by recording your pain level. Health care profes-sionals typically measure pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable. Using this scale as your guide, rate your pain level and record it in your journal a couple of times a day.

You can do this whenever it’s convenient, but keep the times consistent. Many people choose to record their pain level in the morning when they wake up, after lunch and then again in the evening before going to bed.

Keeping a log of your pain levels and activities allows you to:

Learn your pain pattern. Most people find the changes in their pain levels are quite consistent. For example, your pain may be at its lowest level in the morning and its highest level in the evening. Recording your pain levels helps you determine and analyze your pain pattern.

Link your pain with your activities. If your pain is the worst in the evening, why? Look to see if certain activities seem to correlate with an increase or a decrease in your pain level. Are you sitting or standing too long? Is your rush to get dinner ready a contributing factor? Are you just tired? Does isolation make your pain worse?

Identify flares. Recording your pain levels helps draw attention to inconsistencies. If your pain level at noon is normally a 3 and one day it’s a 6, seeing the difference may prompt you to think about your morning. Did you do something different? You can also learn from days when your pain seems more tolerable. Was there something you did that may have lessened the pain?

See your progress. If you feel you aren’t making progress, reading your journal may help you realize that your life has improved, even though the process may seem slow.

Pain scale: Use this scale as a guide when determining your level of pain.

• • • • •

Sample journal

There is no right or wrong way when it comes to keeping a journal. Some people simply like to jot down their thoughts, and others prefer a worksheet format. This is just one example of how your journal might look and the information to include.

• • • • •

Mood

On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being poor and 10 being excellent, rate your mood throughout the day. This exercise helps you realize that even though your pain and your mood are closely aligned, they aren’t bound together.

Typically, the worse your pain, the worse your mood, and vice versa. As you begin to feel more in control of your pain, you may find your mood improving at a faster rate than the improvement in your pain levels. You begin to realize that even though you may not be able to eliminate your pain, you can learn to live with it and still be happy.

Sleep

A good night’s sleep is important. It better equips you to handle your day. However, getting enough sleep can be difficult because your pain may keep you up at night. In contrast, some people spend too much time in bed. This can also reduce your tolerance to pain.

To help you get a better idea of how well you are — or aren’t — sleeping, each day record how many hours you slept during the night and how many times you woke up. Eight hours is about average, but the amount of sleep each person needs varies. Your goal should be to feel rested when you wake up. If you’re having trouble sleeping, tips to help you sleep better are discussed in Chapter 14.

• • • • •

Finding the right doctor

Taking charge of your pain doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t seek help from others. Having people who can help you when you have questions or you need assistance is important. A doctor can be especially helpful. But make sure it’s a doctor who understands your condition and believes in what you’re doing.

The right doctor for you could be your family physician or a specialist who’s overseeing your condition. Or you may want to see a doctor or a psychologist who specializes in pain management (see Chapter 9). If you’re not sure where to find a pain specialist, ask your primary care doctor to refer you to one. Before selecting a new doctor, however, check with your health insurance provider to make sure that the care will be covered under your policy.

When selecting a doctor, look for someone who:

In addition to finding the right doctor, make an effort to learn all that you can about your condition and your pain. This will make it easier for the two of you to work together as a team.

• • • • •

Going forward

Up to this point, we’ve given you a lot of information regarding pain and various options for treating it. The chapters that follow are devoted to specific components of a pain management program. They include topics such as staying physically active, controlling your weight, reducing stress, finding a healthy balance of work and leisure activities, treating depression, and dealing with difficult emotions and behaviors.

In these chapters, you’ll learn about specific steps that you can take to help manage your pain and improve your daily functioning. As you read through these chapters, keep in mind how the two key components outlined here — goal setting and daily journaling — can help you be successful in your efforts to enjoy life with less pain.