‘I’M GOING TO RACE

THAT ONE DAY’

By the beginning of 1972 Peter had vindicated Harry Firth’s faith in him and he was well-ensconced in the HDT. More importantly, Holden was about to provide him with a weapon with which he could better take on the big bad Falcons and his arch enemy Alan Moffat.

The new LJ model Torana XU1 was a little rocket ship containing everything the HDT had learned in the Torana’s development over the previous two years. It was now upgraded with a 202 cubic-inch motor instead of the 186, and this gave a useful increase in power from approximately 170 bhp at the flywheel to just over 190 bhp. While it was some way short of the GTHO’s V8 power, the Holden product was lighter and, consequently, the power-to-weight ratio was almost as good. It also stopped better, handled better and was kinder to its tyres. The stage was set for an interesting year.

The first race of the year was at Surfers Paradise, where the XU1s kept up easily with the Fords, especially when it rained. Although Bond blew an engine and Peter suffered a flat tyre, an XU1 driven by a young Dick Johnson won the race. Peter was still able to finish fourth.

Fast though the new cars were, they experienced a degree of teething problems and were not able to defeat the Falcons. After Surfers there were three indifferent races for the team. In the first, at Warwick Farm, Peter’s XU1 suffered tyre problems and, although he finished the race, he was unplaced. At Sandown he finished fifth, and at Adelaide third. For Peter, though, there was some consolation as in both cases Colin Bond was one place behind him.

Calder, May 1972.

Peter out front, Calder, August 1972.

New paint job LJ XU1, Calder, August 1972.

Sandown, September 1972.

On 12 March, Winton Raceway in central Victoria was the scene for a memorable race because Peter defeated his boyhood idol Norm Beechey, who had forsaken his Monaro and was racing a GTHO Falcon. At thirty laps, it was a relatively short race. For Beechey it was particularly difficult because the tight two-kilometre track meant the GTHO could not stretch its legs while the superior braking and handling of the Torana were a huge benefit to them. Nevertheless, it was a close contest and Peter was justifiably proud of his achievement.

There followed a brace of race meetings. At Calder and Adelaide International Raceway the longer straights were expected to benefit the Falcons. There were three short races at both circuits and Peter finished well up – two second places and a third at Calder, while at Adelaide he won three seconds, plus a lap record for the ‘Improved Production Class’.

Around this time Firth split the racing and from then on Peter and Colin Bond rarely raced against each other in the shorter races. Bond, who was based in Sydney, contested all the New South Wales and Queensland races, while Peter covered those in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. This meant that once again Peter undertook most of the development and test driving since the team was still based in Melbourne. Firth says he began to adopt the European options of setting up a car – making it stiffer with changes to springs and shock absorbers – and this was beginning to pay off.

Winton in early May showed how the shorter tight tracks favoured the Toranas, with Peter greeting the chequered flag in first place three times and taking a well-deserved lap record. A Calder meeting followed, with one podium and a fourth. While the HDT’s racing was going from strength-to-strength, the team was still behind the Ford’s in the promotional area. Firth was notoriously tight with money and while he was willing to spend money on the mechanical side he scarcely looked at the presentation of the cars. ‘We were called “Harry’s Gypsies” by the other teams,’ remembers Tate. ‘The team was also desperately short of such things as tow cars and trailers, which we usually had to borrow.’

Back in 1969 Holden had stepped in and forced Harry to have the Monaro’s appearance improved after complaints from some of the dealers, and the same thing happened in 1972. In the middle of the year Holden’s Director of Sales, John Bagshaw, approached Peter Lewis-Williams to say Holden’s management and the dealers did not like the rather haphazard approach to signage and the overall look of the cars. (Lewis-Williams had left Holden late the previous year, moving to the advertising agency George Patterson to head the GMH account. Joe Felice took over his role with the HDT.) He says, with a smile, ‘Together with the ad agency’s Creative Director, Ian Blain, a new and very distinctive colour scheme was created and approved by Bagshaw. Harry had nothing to do with the decision and he did not pay for it either. By this time the team had plenty of sponsorship money, as well as the funds from Holden, and I controlled the bank account.’

The annual precursor to Bathurst, the Sandown Enduro, was not a good result for the team. Conversely, it gave some optimism. Brock was leading near the end of the race when his engine broke a piston. Bond also suffered the same problem. To the team’s relief the cause was traced to faulty heat treatment of the pistons and not something inherently wrong with the engine. With rebuilt engines the team entered two cars at Oran Park two days later and the result was a one two for the HDT, with Bond winning the race.

‘Pressure’ – Peter chases John Goss, Sandown, September 1972.

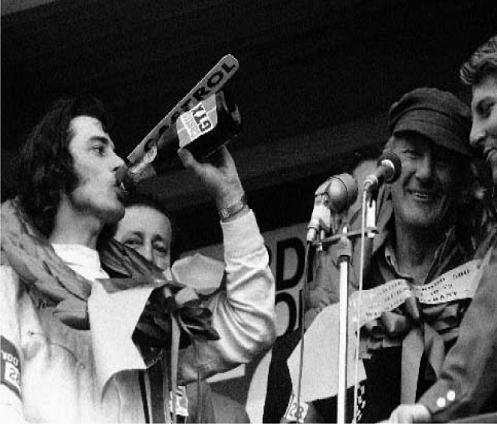

‘Winners are grinners’, Bathurst, October 1972. (Autopix)

The focus then changed to the mountain. Ian Tate says unequivocally that the Peter Brock who faced The Great Race in 1972 was a completely different person to the one who had raced there the previous year: ‘He was a changed man. As well as being very focused, he became a great help around the works, turning up early in the morning and beginning to bond with the mechanics – the Peter Brock of old was gone.’ Tate’s admiration of his friend also increased when he witnessed an act of courage, and it was nothing to do with his race driving. He describes an incident he witnessed, something which he still much admires:

We were driving back from Adelaide International Raceway that year when we came upon an accident involving a Valiant sedan, which had caught fire. Everybody was just standing about helplessly. Peter was still wearing his Nomex racing suit. He calmly reached into his bag, extracted his racing gloves and put them on. Striding to the blazing car he wrenched open the damaged door and, reaching inside, dragged the driver out before returning to the passenger side and repeating the act. They were both farmers and he definitely saved their lives. At the next Calder meeting they came to the track with boxes of fresh produce to thank him.

Peter and Moffat, Bathurst, October 1972. (Autopix)

Even though the team was one of the best in the country, it still did not have a transporter and the cars were either put on a trailer or sometimes driven to a circuit. Bathurst was no different. Tate remembers the road trip to the mountain being nearly as exciting as the race itself. ‘The engines of the car needed to be properly run in, although they had done some miles on the dyno. So, after a few hundred Ks we were able to stretch them a bit and we really pushed it,’ laughs Tate as he remembers the incident-packed drive. ‘We travelled north at a steady 100 miles per hour and then Peter insisted on practicing slipstreaming techniques. We hit 130 miles per hour and Peter would sit close on my tail and then pull out to pass, then drop back again and repeat the manoeuvre. He wanted to know what the Torana would do when it pulled out of the slip stream.’

‘Glory Day’ – Peter and Harry Firth, Bathurst, October 1972. (Autopix)

Peter then changed cars with Tate and drove Colin Bond’s car to ascertain whether the car was different in any way – it wasn’t. There was no open speed limit in those days – the police had to prove that the person was driving dangerously – but in their case it could be argued it was a moot point. Tate says, ‘At one stage I lost sight of him, so I continued, only to discover when I stopped for petrol that we had been travelling so close stones had smashed both his headlights and his windscreen, and he had slipstreamed me for a long time with no lights and no windscreen – and I never saw him; incredible!’

The team was very confident at the mountain. Both Bond and Peter were driving solo and even though the new Torana LJ XU1s were still slower than the GTHO Phase 3s, they were much closer in lap times. Tate says as well as having a significant increase in power, they were a better handling car. There was also a choice of tyres and diff ratios.

Qualifying went without a hitch; Peter was fifth and Bond seventh. Peter qualified only two point four seconds behind the pole sitting GTHO of Moffat, but four-tenths of a second quicker than Bond. Importantly, Peter’s time was set on full tanks.

Race day brought a big advantage for the nimble Toranas – it rained! As the cars lined up on the grid every team manager and driver was wondering whether they had chosen the correct tyres. Firth was seen wandering around the grid checking the tyres of the Fords and then reporting back to his drivers. To this day there is still argument among those who took part over the issue of tyre choice. Firth says Bond chose the tyres he was to race and Bond argues strongly that this was not the case. In this he is backed up by Ian Tate, who says tyres decided the race and the decision was made by Firth.

‘We had a choice of tyres – Goodyear wets, or an intermediate hand-grooved Dunlop tyre,’ remembers Bond. ‘I asked for the wets, but when I lined up on the grid I saw my car was fitted with the intermediates. When I tackled Harry, he argued that the intermediates were the tyres to have since the rain would not last. Unfortunately, I never lasted long enough to prove this because the car was difficult to drive in the conditions.’

The race began in a wall of spray as the cars scrabbled for grip up the mountain. Bond’s run was cut short. At Reid Park he understeered off the road, mounted the bank and rolled his car. Although it landed back on its wheels it was too badly damaged to continue.

On lap 28 Moffat also ran off the road and spun at Castrol Curve, finishing on the grass verge. The car was undamaged and he returned to the track but had lost just over half a minute, allowing Peter Brock to take the lead. Race commentators of the day say the remainder of the race was a game of cat-and-mouse between the lone HDT Torana and the big Fords, plus one of two of the quicker Valiant Chargers, especially the one driven by Leo Geoghegan. Then John French in his GTHO managed to pass Peter, relegating him to second place.

By lap 72 Peter was back in the lead, only to lose it again when he was passed by Moffat. Yet, Peter was not concerned. He knew the Ford driver was carrying two one-minute time penalties and he reasoned Moffat was pushing the car too hard for the conditions. That proved to be the case. A blown tyre necessitated a pit stop for Moffat and with the time penalties he was right out of contention.

A pit stop for the HDT car saw Peter return to the track with a handy lead, but he had incurred a penalty for firing up his engine in the pits before the petrol cap had been replaced. Luckily, this penalty had no effect on the result and he finished the race one lap in front of John French’s GTHO. Not only had he won the race but he had buried his arch rival, Alan Moffat, and, in the words of Harry Firth, ‘stuck it up the Fords.’

Prophetic Words

Eight years previously, in 1964, Peter and some of his friends went to Bathurst for the first time. They were spectators and any thought of driving a racing car there in the future was just a young man’s crazy dream – something almost impossible. Peter’s old friend Al Hamley remembers it well:

Peter saw the track for the first time and wanted to walk it. We all told him we were not interested, it was too far. So, he set off on his own. Two and a half hours later he returned, tired and a little footsore. He had not only walked the course he had examined every corner, every dip and every nuance of the place. All he said in a very determined way was:

‘I‘m going to race that one day!’

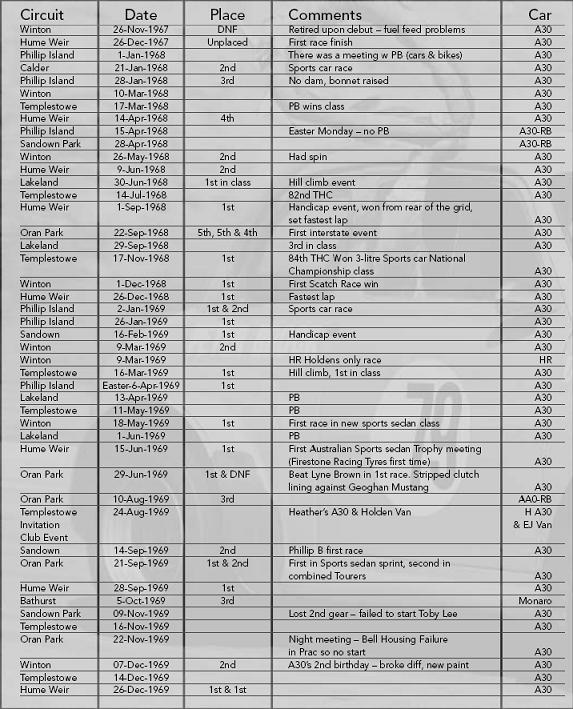

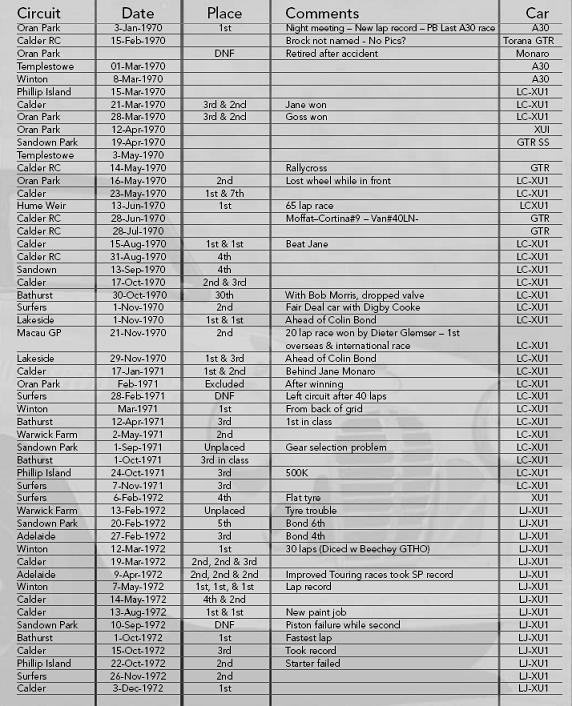

PETER BROCK – RACE HISTORY 1967–1972