A protestor responds to image of Jair Bolsanaro

Such cyclical worldwide outbreaks and resurgences of popular protest suggest that a common set of social processes link social movements across national contexts and international borders. From theoretical and empirical work on social movements in the world-historical perspective,1 we find that protests located in different countries and regions are linked, in both incidence and intensity, through several global historical structures: world-scale structures of governance; global political processes; the hierarchy and networks of the world-economy; and cycles of global economic hegemony and rivalry. However, due to methodological and perceptual limitations, only a small number of studies have analyzed worldwide patterns and processes behind protest waves (for notable works, see Martin 2008; Silver 2003).

This chapter offers an account of the world-historical patterns for two protest waves in the global South: the 1930s and the early 2010s. In the process of analyzing these two protest waves, several questions emerged: (1) where to locate these protests in the changing trajectory of geopolitics and the world-economy; (2) how much the protests can be defined by a shared similarity of theme in their struggles; and (3) how such an analysis can contribute to understanding protest waves in the global South. Based on empirical findings, I will examine in particular a key premise of world-systems studies. The semiperiphery is a key spatial region for initiating transformative actions and protest waves against the dominant hegemonic structure of the capitalist world-economy (see Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2006; Chase-Dunn 1989, 1990).2 Based on my research findings, I argue that while this was true of the protest wave of the 1930s, that of the 2010s was in fact concentrated in the global South. Furthermore, I assert that popular protests in the global South are characterized by one of two themes, each of which contests dominant hegemonic constraints and contributes to the protests’ successive growth and expansion: the struggle against exclusion and the struggle against exploitation.

Data and Method

To map out the world-historical patterns that structured the two protest waves, I have used The New York Times from 1870 to 2015 as my historical source. The New York Times has been widely acknowledged as one of the best single newspaper sources for social movement event data, as it has reported more events and provided more detail than any other singular newspaper source.3 Located in a hegemonic country, the United States, this source has had a significant interest in covering disputed areas of the global South in the era of US hegemony . Using the newspaper database , ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times, I identified protest events by searching the following keywords from article titles (headlines): protest, rally, revolt, rebel, riot, demonstration, uprising, unrest, and strike. I selected for forty-three countries/regions located in the global South with the highest number of protest events because of data reliability.4 I hand-coded a total of 20,000 protest events into a database.5 Thus, the database provides a unique source for data on major revolutions, rebellions, revolts, civil strife, insurrections, insurgencies, uprisings, and turmoil (riots, demonstrations, protests, etc.) in the global South.

Protest Waves in the Global South: 1930s and 2010s

Identification of Two Protest Waves: Long 1930s and Short 2010s

Protest waves in the global South‚ 1870–2015

Protest waves of the 1930s and the early 2010s

1930s | Early 2010s | |

|---|---|---|

Duration (year) | 11 years (1927–1937) | 4 years (2011–2014) |

Total number of protest events | 3377 | 729 |

Annual average | 307.0 | 182.3 |

Peak year (frequency) | 1931 (449) | 2011 (278) |

While each protest event has its unique national context, history, and development, there are some common trajectories which should be considered in order to advance empirical understanding of the 1930s and early 2010s protest waves. The starting point for such considerations is the nature of the world-economy, which is defined by a seamless, deterritorialized process of capitalist globalization. According to Silver and Arrighi (2011, 54), “in both periods, finance capital rose to a dominant position in the global economy relative to capital invested in production. In both periods, moreover, the financialization of economic activities proved destabilizing and culminated in major crises, notably in 1929 and 2008.” They also argue that these “financial expansions historically have been periods of hegemonic transition ... setting the stage for a new material expansion on a world scale” (Silver and Arrighi 2011, 59; about the process of hegemonic transition, see Arrighi and Silver 2001).

The period of transition from British to US hegemony was a period defined by widespread warfare and repeated economic crises. In the early twentieth century, the expansion of colonialism meant that the rest of the global South had been incorporated into the world-economy. The world-economy of capitalism penetrated all parts of the globe, which is why the Great Depression would represent such a landmark in the history of anti-imperialism and national liberation movements in the global South (Hobsbawm 1995, 204). During the long 1930s, capitalist strategies of relocating certain production processes to peripheral zones led to the rise of nationalism and national liberation struggles for decolonization in Asia and Latin America. The increasing peripheralization of Latin America brought on a massive political mobilization of peasants who had come to be heavily involved in the global market economy and shifted the locus of conflict to the struggle between the masses of the global South and ruling classes within their zones.

Over the period of capitalism in crisis at the end of the long twentieth century, the financialization of global capital has led to growing levels of poverty, inequality, and precarity. In particular, the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009, which saw the implosion of the US financial system, and the subsequent sovereign debt “euro crisis,” created conditions in both the global North and the global South in which massive austerity programs displaced workers, raised the cost of living, and spurred the growth of the precariat (Benski et al. 2013, 544). Although the Arab Spring has been portrayed as a primarily political mobilization, as Tejerina et al. (2013, 380) argue, its “antecedent conditions ... are to be found in the increasing levels of social inequality that accompanied global capitalism as it became globalized, financialized, and legitimated by neoliberalism.” In sum, the early 2010 global South protest wave, despite its shorter duration, had been reflected by a world-historical dynamics of capitalism—namely the current period of capitalism-in-crisis.

Regional Composition/Diversity

Distribution of protest events by region‚ the 1930s and the early 2010s

Top countries for annual average of protest events in protest waves, the 1930s and early 2010s

1927–1937 | 2011–2014 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Country | Rate (%) | Region | Position in the World-Economy | Country | Rate (%) | Region | Position in the World-Economy |

China | 18.3 | Asia | Semiperiphery | Syria | 19.8 | MENA | Periphery |

Mexico | 16.7 | Latin America | Semiperiphery | Libya | 13.2 | MENA | Periphery |

Cuba | 9.3 | Latin America | Semiperiphery | Egypt | 12.4 | MENA | Periphery |

Brazil | 6.7 | Latin America | Semiperiphery | Ukraine | 6.5 | Europe | Periphery |

India | 6.1 | Asia | Semiperiphery | China | 5.5 | Asia | Semiperiphery |

Poland | 5.2 | Europe | Semiperiphery | Russia | 4.4 | Europe | Semiperiphery |

Nicaragua | 4.9 | Latin America | Periphery | Iraq | 3.3 | MENA | Periphery |

Argentina | 4.3 | Latin America | Semiperiphery | Hong Kong | 3.3 | Asia | Semiperiphery |

Peru | 2.5 | Latin America | Periphery | Palestine | 3 | MENA | Periphery |

Hungary | 2 | Europe | Semiperiphery | Turkey | 2.5 | MENA | Semiperiphery |

Unlike the protest wave of the 1930s, the early 2010s wave shows a limited regional distribution of protest events: 58% occurred in the Middle East and North Africa (see Fig. 12.3). In particular, a majority of events were concentrated in only a few countries in the Middle East and North Africa such as Syria (20%), Libya (13%), and Egypt (12%) (see Table 12.2). According to the dataset, the 2010s wave encompasses the following major protest episodes: the Sudanese nomadic conflicts from 2010 to 2014; the Egyptian Revolution from 2010 to 2014; the 2011 Tunisian Revolution; the 2011 Libyan Civil War; the nationalist mobilizations in China, including the 2011 Shanghai truckers strikes and the 2012 anti-Japanese demonstrations; the 2011–2013 Russian protests; the Syrian Civil War from 2011 to 2015; the Gezi Park Protest in Turkey in 2013; the 2013–2014 Thai political crisis; the Ukrainian Revolution in 2014; and the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement in 2014.

Comparative studies in social movements have increasingly highlighted the existence of striking similarities between kindred movements in different locations (see della Porta and Rucht 1995). These similarities can be explained by both internal variables and by external factors. It is likelier that diffusion takes place between locations that are closer together geopolitically and culturally, as well as between countries/regions with a history of past interaction (Strang and Meyer 1993, 490). The protest wave of the early 2010s—in particular, the Arab Spring—is a clear example of this idea, as the Arab Spring reflected regional factors.7

Position of the World-Economy: From Semiperiphery to Periphery

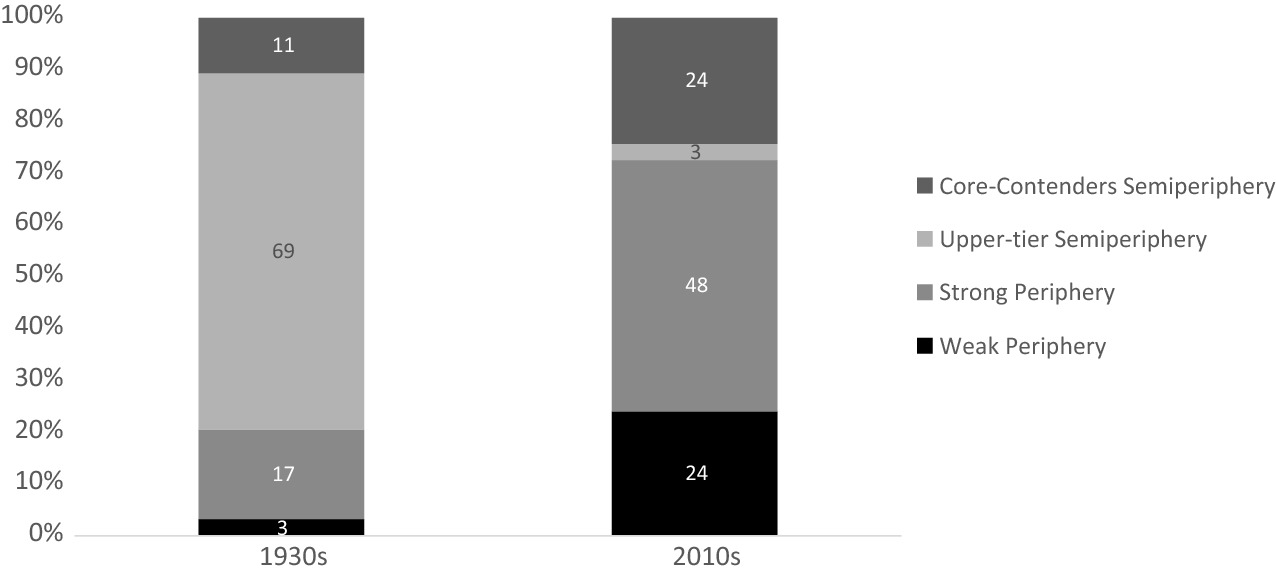

Distribution of protest events by position in the world-economy‚ the 1930s and the early 2010s

Countries/regions in the semiperiphery and periphery of the world-economy, the 1930s and 2010s

1930s | 2010s | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Semiperiphery | Core-contenders | Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic), Hong Kong, Hungary, Poland, USSR (Russia ), Yugoslavia (Serbia) | Argentina, Brazil, China, Czech Republic, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, South Korea , Mexico, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Turkey, Thailand |

Upper-tier semiperiphery | Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Cuba, India, Mexico, Pakistan, Romania, South Africa, Turkey, Ukraine | Bulgaria, Chile, Colombia, Indonesia, Philippines, Romania, Serbia, Vietnam | |

Periphery | Strong periphery | Algeria, Colombia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Korea, Lebanon, Morocco, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, Syria, Thailand, Tunisia, Venezuela | Algeria, Cuba, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Myanmar, Pakistan, Peru, Sudan, Tunisia, Ukraine, Venezuela |

Weak periphery | DR Congo, Kenya, Libya, Myanmar, Palestine, Sudan Vietnam | DR Congo, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Palestine, Syria |

Struggles Against Exclusion Over Struggles Against Exploitation

Antisystemic movements are categorized around two main ideas: labor-socialist movements and nationalist movements. According to Arrighi et al. (1989, 30–31), “the social movement defined the oppression as that of employers over wage earners, the bourgeois over the proletariat .... The national movement, on the other hand, defined the oppression as that of one ethno-nationalist group over another.” However, the distinction between the two varieties of antisystemic movements has become blurred (Wallerstein 1995, 71). Indeed, as Amin (1990, 116) asserted, most antisystemic movements in the global South have overlapped these two dimensions “in the expression of their revolt” with “a national dimension and a social dimension whose content was more or less radical depending on the circumstances,” or could not be organized in these two categories because some societies in the global South had already achieved a full nation-building process or the class contradiction in their social formations was still underdeveloped. Hence, we need to develop a more inclusive concept focusing on the primary themes of movements, struggles against exploitation and struggles against exclusion, to examine the nature of antisystemic movements such as diverging types of organization, articulated goals and claims, and method of struggles in the global South.

Struggles against exploitation are social movements that challenge the processes of exploitation. The struggles against exploitation in the global South have mobilized people to demand an end to their absolute or relative poverty, austerities, and economic grievances and to resist local economic elites, who would have them participate in the world-historical division of labor for marginal rewards. On the other hand, struggles against exclusion are social movements that contest processes of exclusion from local/domestic/international communities and polities. In particular, two predominant historical processes of exclusion in the global South are “incorporation” and “nation-building” (see Dunaway 2003). These dual processes of incorporation and nation-building have been structured mainly by racism and ethnic discrimination, and this has proved one of the prime causes of national liberation conflicts in the global South. Furthermore, the idea of struggles against exclusion could extend to the issues of displacement and resistance. These struggles encompass political and cultural struggles over sovereignty, limited autonomy, sociopolitical inequality, ecological issues, and minority status and rights in the global South (for a more detailed exploration of this idea, see Jung 2015).

The theme most widely shared by popular protests in both protest waves was the “struggle against exclusion.” Between the two protest waves, the absolute numbers for protest events characterized as struggles against exclusion and struggles against exploitation decreased, from 2595 to 689 and from 784 to 43, respectively. However, struggles against exclusion represented the primary claim in 77% of total protest events from 1927 to 1937 and 94% of total protest events from 2011 to 2014. This finding shows that struggles against exclusion have remained a primary issue of popular protests in the global South at the beginning and end of the long twentieth century.

Struggles against exploitation and exclusion by countries/regions, the protest wave of the 1930s (42 countries/regions)

Struggles against exploitation and exclusion by countries/regions‚ the protest wave of the early 2010s (38 countries/regions)

Conclusion

For the global South, the 1930s and 2010s were two of the most revolutionary periods in the long twentieth century. By mapping out the world-historical pattern of protest events using The New York Times, I distinguish several key juxtapositions between the two protest waves. First, the compiled data identified two global protest waves, from 1927 to 1937 and from 2011 to 2014, that had occurred in periods of world hegemonic transition and capitalism in crisis. During the rise of US hegemony and the period of the Great Depression, many protest events happened in the global semiperiphery, while during the decline of US hegemony after the Great Recession, most protest events emerged within the global periphery. This empirical finding could challenge the long-established notion that the semiperiphery constitutes the key region for making transformative actions and protest waves. It also suggests that while popular protests are associated with economic and geopolitical crises, the locus of revolutionary activity in the global South is changing along with the world-historical context. Moreover, the most widely shared theme of popular protests—struggles against exclusion—was consistent in both protest waves across regions in the global South. This finding implies that struggles against exclusion remain a central issue of popular protests in the global South over the long twentieth century.

But a key question remains: did the global South protest wave of the early 2010s have a counter hegemonic capacity, that is, the ability to break down the dominant hegemony of the capitalist world-economy? Crisis in capitalism has grown as a global scale, not only in the global semiperiphery but also in the global periphery. However, counter hegemonic activities have paradoxically dispersed in the global semiperiphery. As the crisis increases and deepens, a centripetal force and convergence of antisystemic movements resisting this crisis have weakened more than ever before in the global semiperiphery. Compared to the 1930s, the early 2010s protest wave was clustered in a relatively limited number of regions and countries. Its frequency was relatively lower and its duration relatively shorter when compared to past protest waves. Finally, unlike the 1930s, which led to systemic transformations to the world capitalist economy—the “revolutionary thirties” as Karl Polanyi put it ([1957] 2001, 21), the recent protest wave seems to have lacked substantive programs and strategies capable of challenging the hegemony of the capitalist world-economy, and the outcome of the protest wave at a world scale remains uncertain.