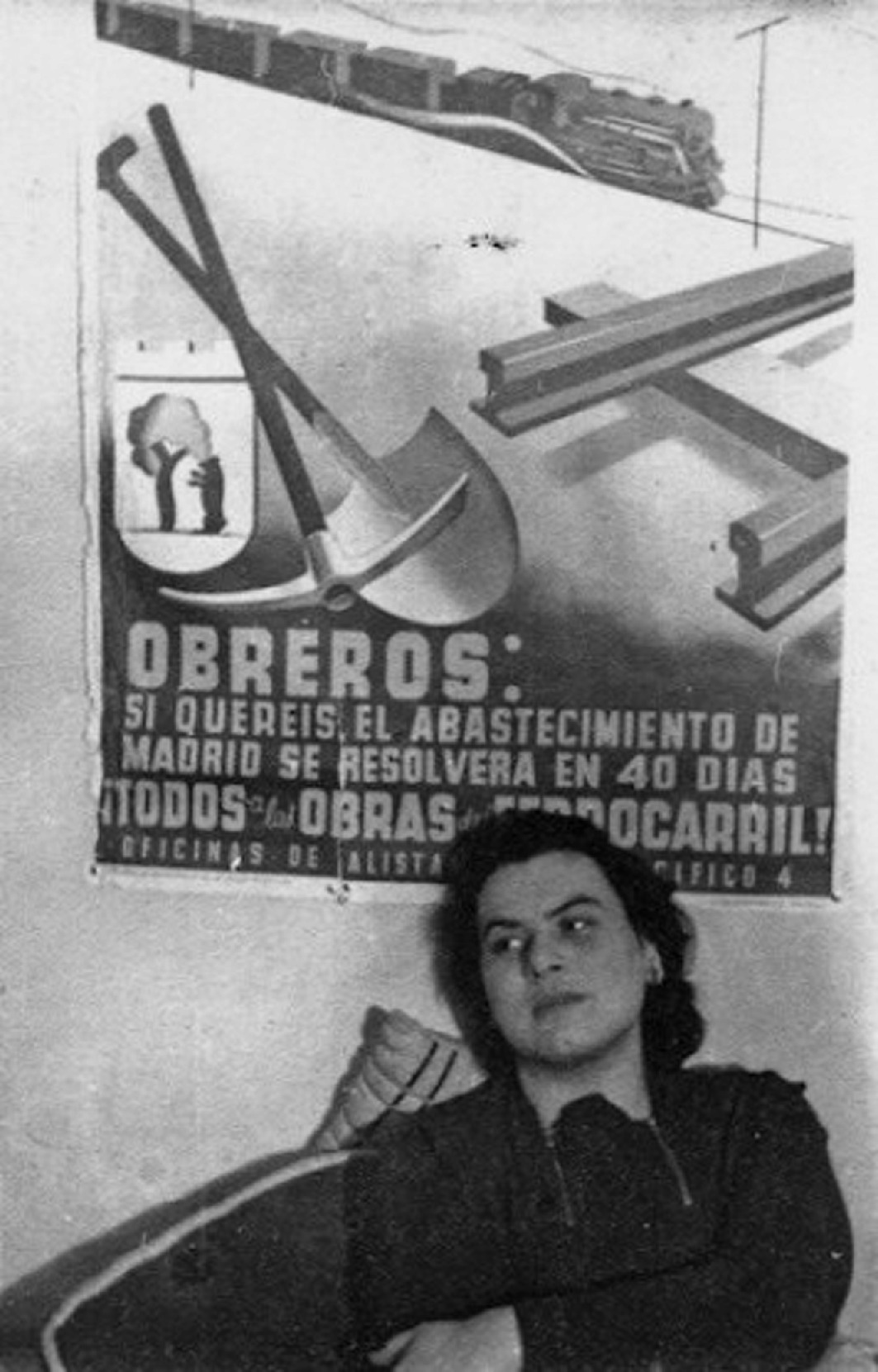

The poet Muriel Rukesayer

His is not a medical condition but an affective one. Even from the stasis and isolation of prison, Nâzım is so wrapped up in the people and events of the outside world that his heart is worn down with excessive use. The ability to identify with the struggles of strangers and to celebrate or mourn along with them, even the ability to feel into the suprahistorical vast distances of the cosmos—this is the cause of his battered organ. He carries this bad heart in his chest like a badge of honor.

This chapter focuses on a generation of communist poets that spent the long 1930s “changing our country more frequently than our shoes,” as Bertolt Brecht once quipped. Nâzım Hikmet (Turkey), Yannis Ritsos (Greece), and Langston Hughes and Muriel Rukeyser (USA) responded to the rise of fascism and global economic crisis with communist internationalism. Whether able to physically cross borders, or else identifying with parallel struggles from the confinement of their prison cells, these radical writers developed aesthetic techniques and poetic modes consonant with the danger and the promise of the 1930s. Madrid, Harlem, Shanghai, Addis Ababa, Rome, Salonica, and Istanbul all appear as subjects and settings in their poetry. The words of these poets were just as mobile as their bodies or hearts. Their writings were rapidly translated into other languages and published through cultural networks supported by the world communist movement. Their poetry addressed not just national or elite audiences but, potentially, all of humanity. Closer to reaching this goal than we might imagine, their poems were put to immediate use, often in ephemeral forms like in pamphlets and broadsides that crisscrossed the globe.

Nâzım, Ritsos, Hughes, and Rukeyser are just a few representatives of a larger grouping that Aijaz Ahmad has named “Poetry International” (2000). The term describes poets “from Latin America, the Arab world, the Caribbean, Europe, Central America and South Asia” who, as Marxists, lived and wrote “as part of a global fabric.” They formed a generational cadre that Michael Denning has dubbed “radical moderns” (1998, 39). These committed cultural producers were born in the first few years of the twentieth century; lived through World War I; were politically and artistically radicalized in the 1920s, aligning themselves with the international labor movement and the artistic avant-garde; experienced the global economic crisis and Great Depression; and participated in the Popular Front and antifascist struggles of the 1930s. Denning’s use of the term “radical modern” is focused on the USA. However, if we combine these two concepts, then our four poets—with their globe-trotting biographies and links to other writers—are both radical moderns and participants in Poetry International.

Other thinkers have also observed that the 1930s created a rare moment of international convergence for art and culture, just as it did for the politics of solidarity. In “Poetry and Communism,” Alain Badiou notes the remarkable fact that “last century, some truly great poets, in almost all languages on earth, have been communists” (2014, 93). What were the literary/institutional/personal networks that made this truly international convergence possible? The Soviet Union played an essential role for the work of radical moderns. Katerina Clark reminds us that “around 1935 Soviet cultural leadership was a distinct possibility throughout the transatlantic world” (2011, 27). With Moscow vying with Paris (and Berlin or Mexico City) as a cultural capital of the world, artists and intellectuals across the globe found themselves “enticed by the possibility of a transnational cultural space, an intellectual fraternity of leftists” (31). Marxism was a source of exhilaration for writers—and not only in the transatlantic world. Soviet support for anti-imperialism increased this attraction, bringing in many intellectuals in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, as well as African Americans. The Comintern was “the only European political organization to declare the equality of the races and to officially embrace anti-imperialism” (Kent and Matera 2017, 9). As Robert Young remarks, communist parties were attractive across the three continents precisely because they provided tools for articulating the links between international and national struggles (2001, 169). Culturally, this movement was one of the few ways peripheral writers could gain a worldwide readership.

A tense, paradoxical, violent love of life in common …. The poetic desire that the things of life would be like the sky and the earth, like the water of the oceans and the brush fires on a summer night—that is to say, would belong by right to the whole world. (93–94)

These politically committed poets are tied together by an emphasis on the rather unexpected theme of love. Love and commitment, poetry and communism: These pairs seem to correspond to that old literary-historical binary of lyric (the genre of love and subjective experience) and epic (a historical, public genre). These two poles are not opposed in Poetry International. One can compose a love poem for masses of strangers, just as one can write about the most private, subjective dimensions of an historical event. Their epistolary poems, for example, effortlessly shuttle between erotic longing addressed to a single individual and political musings that hail a collectivity. This love most often takes the form of internationalism (a love for the common struggles of strangers) and a calling into being of “the people” (shared bonds of love within a national collectivity). Radical moderns use the same poetic-political technique for expressing both internationalist commitment and a focus on one’s own “people”: identification, or the poetic ability to imagine oneself into the experience of others.

One last note is needed to define the basis of the comparison undertaken here. Many of the poets from this mostly male milieu3 met face to face (Nâzım and Ritsos, for example), often becoming close friends. They sometimes fought for the same causes (Hughes and Rukeyser for the Scottsboro Nine; Nâzım Hikmet and Hughes against the Italian invasion of Ethiopia), and all supported the Republicans in Spain (Rukeyser visited Spain; Hughes came to Spain on Pablo Neruda’s urging; both Rukeyser and Hughes contributed to an anthology of Spanish Civil War poetry). Some translated each other’s work (Ritsos published Greek versions of Nâzım’s poetry). Some dedicated poems to each other (Ritsos for Nâzım, Rukeyser for Neruda). Mutual influence and direct contact partially explain their thematic and formal similarities, but most significant is how these poets share a common historical situation as the ground of their common aesthetic and thematic preoccupations.

No matter what his country or what his language, a writer, to be a good writer, cannot remain unaware of Spain and China, of India and Africa, of Rome and Berlin. Not only do the near places and the far places influence, even without his knowledge, the very subjects and material of his books, but they affect their physical life as well … (2002, 199)

World events and a Marxist-ish orientation toward them—these cannot but have consequences for the poet’s work. It is not surprising therefore that the members of the Poetry International wrote on similar topics in poems appearing in the same venues. What is remarkable, rather, is that these poets utilized the same forms and exhibited parallel attitudes even before they were aware of each other’s poetry.

It was the Popular Front that set the historical groundwork for these common aesthetic approaches and attitudes. The policy of the People’s Front Against Fascism and War, formalized by the Comintern in 1935 and technically abandoned in 1947, made new political alliances possible. First developed to counter the threat of Nazi Germany, the Popular Front became a wider strategy of “capitalist-communist alliance against fascism” (Hobsbawm 1996, 7.) The Popular Front also gave rise to new artistic genres, attitudes, and modes of identification—in short, a whole structure of feeling. It led to a search for what united people across (and within) linguistic, cultural, religious, national, and factional borders.

In describing a “Popular Front structure of feeling” I am drawing on Raymond Williams, who developed the concept to describe the “particular quality of social experience and relationship, historically distinct from other particular qualities, which gives the sense of a generation or of a period” (1977, 131). Structure of feeling describes the style an era. A feeling is in the air, so to speak, but it must be tracked through its various concrete expressions, often appearing in far-flung places. A structure of feeling is “a structure in the sense that you could perceive it operating in one work after another which weren’t otherwise connected—people weren’t learning it from each other; yet it was one of feeling much more than thought—a pattern of impulses, restraints, tones” (1981, 159). The concept is particularly apt for cultural periodization because it links political developments and economic modes with styles, aesthetic trends, affects, and psychic experience. Looking at how geographically distant poets produced similar work in the same period provides a helpful laboratory case for tracking the 1930s structure of feeling. The omnivorous, ecumenical, promiscuous, combinatory sensibility of the Popular Front can be best glimpsed in the poetry of the period. Lyric poets, if we follow Badiou, are inclined to search for what is common across difference. In this way, radical moderns were well suited to internalize and subjectivize the Popular Front.

After reanimating the 1930s style through brief readings of our poets, this chapter will address the relevance of Poetry International today. Many sense in the air of our own historical present a similar feeling of danger (with the rise of nativist, right-wing authoritarianism and a new crisis for liberal democracy) and promise (the reentry of socialism into popular discourse, the growth of left-wing art and culture) as the 1930s. While the writings of Poetry International can provide affective and aesthetic resources to readers today—and poems by radical moderns do reappear at certain key moments4—aspects of Popular Front culture inevitably come across as dated and even cloying under contemporary conditions of what Lauren Berlant describes as twenty-first-century “post-Fordist affect”: the human “sensorium making its way through a postindustrial present, the shrinkage of the welfare state, the expansion of grey (semi-formal economies) and the escalation of transnational migration, with its attendant rise in racism and political cynicism” (2011, 19). As inchoate as today’s structure of feeling might be, one thing is certain: our own cultural dominant is highly allergic to sentimentality and over-earnestness. If love or populism no longer feel as readily accessible to us, what affective modes can a contemporary communist art draw upon? We cannot simply apply strategies or approaches from the 1930s to our own moment. However, exploring that incredible moment of convergence might help us better delineate what our own present is, and from there what our future might be.

Internationalism and Love

In 1948, the same year Nâzım wrote “Angina Pectoris” but unknown to him, Yannis Ritsos was composing a similar poem. Not far across the Aegean Sea, in a concentration camp for political prisoners on the Greek island of Lemnos, the hearts of Ritsos and his fellow inmates were aflutter with the good news coming in from China:

The language of politics mingles with the language of love as these prisoners track the precise movements of the Red Army from their own position of immobility:

The Greek antifascist partisans may have been defeated in the Civil War (1946–1949), but if the comrades across the world can capture Beijing, then all is not lost. Ritsos calls this act of imaginative substitution “lov[ing] each other.” The radical moderns who articulated this poetic practice of identification through love continued elaborating it after the war. Yet the 1930s was the high point of this global turn in how politics and aesthetics were imagined.

The catalog or list was a central technique for the expression of bonds of solidarity in Poetry International. Langston Hughes begins one of his first explicitly communist poems, “Merry Christmas” (1930) with a catalog of world locations and events. He starts with China, still early on in its civil war:

Hughes goes on to list India (“Gandhi in his cell”), England (“righteous … Christian”), Africa (“From Cairo to the Cape! … For murder and for rape”), as well as the USA (“Yankee domination”). The oppressed and colonized of the world are called into collectivity through their shared naming, creating what Michael Thurston calls a “roll call” of identifications (2001, 91). Such lists not only name alliances, they are calculated to stir a certain awe in the reader regarding the breadth of this love and the length of its connections: Hughes discovers friends and enemies “[i]n the docks at Sierra Leone,/In the cotton fields of Alabama, … /And the cities of Morocco and Tripoli” (165). These list-poems suggest that to not only imagine but physically feel the pain and joy of others is the psychic complement of revolution. These lists bring intersectional alliances into being: “the Red Armies of the International Proletariat/Their faces black, white, olive, yellow, brown” (166). To love is to know that others will call your name just as you call theirs.

In the poetry of radical moderns, specific place names become signifiers for events with global implications. The most charged proper noun in the litany of the turbulent 1930s was “Spain.” For many on the Left, the Spanish Civil War was the defining struggle of the age. Spain was the object of numerous poetic tributes. Nâzım’s contribution to this micro-genre of the Spain-poem is “It Is Snowing in the Night” (1937). The description of an unknown sentry protecting Spain’s Republican-held capital pinpoints how love functions for Poetry International:

The speaker addresses the unknown sentry with great tenderness. He loves him and regrets his geographical distance:

Here the discourse of politics folds into the language of love. This is partly a function of genre. Lyric poetry, and the wider Romantic mode in the arts, has at its ideological core the claim to imagine and portray the experience of others, to form identifications across distance. Nâzım practices an extravagance of identification. The ability to envision what is common is the psychic corollary of the broad coalition. For radical modern poets, the Popular Front was not just a political strategy for defeating fascism; it had a corresponding aesthetic practice and even affective disposition. Referring to the massive global outpouring of solidarity with the Spanish Republican cause, Hobsbawm notes that “intellectuals and those concerned with the arts were particularly open to [the Popular Front’s] appeal” (149). The brutal murder of even a non-militant poet like Lorca confirmed the suspicion of many artists in the 1930s that fascism and art were mortal enemies.

Muriel Rukeyser also saw a connection among art, love, and revolution in Spain. In “Letter to the Front” (1944) she recalls her experience in 1936, “Coming to Spain on the first day of the fighting/Flame in the mountains, and the exotic soldiers,/I gave up ideas of strangeness” (2006, 241). Witnessing the war break out near Barcelona she saw volunteers join the conflict. This act of international solidarity caused her to reflect on the wider meaning of the Spanish war: “Free Catalonia offered that day our changing/Age’s hope and resistance, held in its keeping/The war this age must win in love and fighting” (241). Love and fighting are intimately connected in Spain, which became a struggle to redeem the age. In her 1937 poem “Mediterranean,” printed in a booklet requesting medical donations in exchange for “the heartfelt thanks of a heroic people,” Rukeyser described a less abstract form of love (608). While traveling by ship to cover the antifascist People’s Olympiad in Barcelona, she met an athlete: “the brave man Otto Boch, the German exile” (145). The poem describes his “gazing Breughel face,/square forehead and eyes, strong square breast fading,/the narrow runner’s hips.” When the Civil War broke out five days into Rukeyser’s stay, she was evacuated with other civilians while Boch stayed on to join: “Otto is fighting now … /No highlight hero. Love’s not a trick of light” (150). Boch died in battle in 1938. He reappeared in Rukeyser’s poems and prose writings throughout her career as a nexus point of erotic love, love of struggle, and sacrifice. His beauty is a placeholder for the life that would have been—had Spain been victorious.

the nostalgia for a grandeur and a beauty that have not yet been created. Communism here works in the future anterior: we experience a kind of poetic regret for what we imagine the world will have been when communism has come. (2014, 104)

This communist tense expresses “nostalgia for that which the world would be if this possible creation had already taken place.” Whatever happens, the city of Madrid—like an object of great beauty lost to time, or else a beautiful person now martyred for a cause—once existed. Or the example of the lone sentry standing in the snow: even if just a figment of the poet’s imagination, he continues to inspire a nostalgia for the future. Through identification, love holds open possible futures. In 1938’s The Book of the Dead, Rukeyser was aware that the conflict held significance far exceeding just Spain or her own historical moment. Back in the USA, she sees: “flashing new signals from the hero hills/near Barcelona, monuments and powers” (2006, 108). Linked together, parallel struggles are compressed into “seeds of unending love” that may sprout in the future (111).

Badiou’s reading confirms what the poetry shows: the communist poetics-politics of the 1930s is focused on a “changing of subjectivity” (2014, 101). The love expressed in radical modern poems is centered on a practice of collective feeling. A coalition grounded in love despite distance and difference: this is what will have been established in human hearts when the brave volunteer is victorious. The poet too is like a sentry, keeping alive a vision of the world, however oblique, “from the standpoint of redemption” (Adorno 2005, 247).

Loving “The People”

Radical moderns were not only concerned with international identifications and the communist future but also national space and its historical past. One product of the Popular Front emphasis on the national-popular was new aesthetic approaches incorporating folk forms and even formerly taboo subjects like religion. In attempting to reach greater audiences, radical moderns not only produced poems about the people, they produced poetry for them. Poetry International used popular forms and tropes in order to stake new claims for love’s power to unite a national collectivity.

Salonica. May 1936. In the middle of the road a mother sings a dirge over her slain son. Waves of demonstration—the striking tobacco workers—roars and break around her. She continues her lament. (1986)

Ritsos composed the poem after seeing a newspaper photograph of this mourning mother. Her lament spans twenty sections of eight couplets containing elaborate images designed to elicit maximum pathos in the reader.

Her political awakening begins when she questions why he was killed: “You asked for a bit of bread and they gave you a knife” (43). Moved by the piteous sight, the youth in the crowd comfort her. She begins to understand her son’s struggle: “I see thousands of songs … They speak to me the way you used to … / and they have your cap, they are wearing your clothes” (45). Through this new class-consciousness, she joins the workers, who unite with other sections of society:

The son is resurrected in the mother. She rises from the ground and declares: “My son, I’m going to your brothers and sisters and adding my rage. / I’ve taken your rifle. You, go to sleep my bird” (51). Love and rage are one.

Like the dirge on which “Epitaphios” is based, the poem moves from death to the promise of resurrection. Just as Mary and her companions mourn Christ, so the mother mourns her son with his fellow workers. The use of the familiar metrical form of decapentasyllabic rhyming couplets is no accident, as the poem’s translator remarks: “the ‘Epitaphios Thrinos’ is known to all speakers of the language: men and women, young and old, rich and poor, educated and uneducated, of all political persuasions” (5). By mimicking the form and themes of a familiar cultural object, Ritsos showed that love was also about knowing one’s audience. In adopting church liturgy, Ritsos offered a new vision of what it meant to be Greek. The authorities registered the danger of this alternative: Dictator Metaxas had Ritsos’ poem ritually burned at the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens in 1938.

With its impassioned call for antifascist solidarity across the divisions of the body politic, Nâzım’s “Epic of Sheikh Bedreddin” (1936) is also a locus classicus of the Popular Front aesthetic. The poem describes a fifteenth-century uprising in the Ottoman Empire led by the heretical proto-communist Sheikh Bedreddin. The story comes to its climax with the clash of the Sultan’s forces with the ragtag army of the sheikh’s followers. The army fighting to be “everywhere/all together/in everything” is composed of the whole range of Anatolian cultures: “Turkish peasants from Aydın,/Greek sailors from Chios,/Jewish tradesmen.” All fight under the same “green-and-red flags” (Blasing 58). Ten thousand people band together because they share the same vision:

By emphasizing the multi-ethnic, multi-confessional character of the uprising, Nâzım presents a fresh vision for intersectional alliances in the 1930s. In a postscript to the poem, he expressed pride that Anatolia “gave rise to a movement that considered the Greek sailors of Rhodes and Jewish merchants as brothers” (Ertürk 2011, 175). This left-populist vision is “national” without being chauvinistic. In “Bedreddin,” Nâzım elaborates an event ostensibly within national historiography, but challenges official Turkish nationalism (built on the ethnic cleansing and genocide of non-Muslim minorities) by articulating an alternative understanding of who “the people” might be.

Radical moderns invested the Popular Front strategy of national alliances with an affective charge through overlapping identifications. For example, in Hughes’s “Let America Be America Again” the speaker declares:

This expansive first person invests American populist platitudes with new meaning. It draws on a key figure from the US usable past: Walt Whitman. In “Song of Myself,” Whitman identified with a “boatmen and clam-diggers,” “a red girl,” and “a runaway slave,” whom he protects. This poetic persona possesses an indefatigable ability for identification. In Hughes’ hands, identification is not mere humanistic fellow-feeling but the active forging of solidarity. Whereas Whitman idealized the USA as a radical democratic project, it is impossible to confuse Hughes’ poem with patriotic nostalgia (or with the Trumpian slogan that it superficially resembles). “Let America Be America Again” is punctuated with the chorus: “America never was America for me” (189). The country is described not in terms of an ideal past but as a future-oriented project: “And yet I swear this oath—/American will be!” The poem’s “I” will be part of a “land that’s mine—the poor man’s Indian’s, Negro’s, ME” (191). Hughes imagines a provisional form of interracial solidarity or “politically necessary coalitions” (Thurston 87) that create not sameness in the present but set the groundwork for a kind of working-class love in the future.

Denning argues that in the USA, the growth of a “Popular Front public culture sought to forge ethnic and racial alliances … by reclaiming the figure of ‘America’ itself” (1998, 9). A new “antifascist common sense in American culture” uncovered heroes and events that could be reinterpreted in terms of the present. For example, Rukeyser draws on the life of abolitionist John Brown (who raided the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in 1859 with a cross-racial band of comrades) to articulate a usable past and potential future for the USA within a larger internationalist framework. In 1935’s “The Lynching of Jesus,” remembering is a form of love. At nineteen, Rukeyser left Columbia University to travel down to Alabama in support of the Scottsboro Nine. (This famous case of nine African American children falsely accused of raping a white woman became a central campaign of the USA 1930s.) Rukeyser’s poem connects the “red brick courthouse” in Alabama to the trials of other revolutionary martyrs:

She uses religious imagery for these famous deaths, seeing both resistance and repression as part of an eternal cycle going back to Christ: “this latest effort to revolution stabbed/against a bitter crucificial tree” (25). She offers an international roll call of the “[m]any murdered in war, crucified, starved,” including “Shelley, Karl Marx” (26) and “the lynched five thousand of America” (30). This sweeping historical vision creates a genealogy out of a national and international history of struggle that will end, like the religious narrative, in resurrection: “eternal return, until/the thoughtful rebel may triumph everywhere” (25). Out of defeat, victory.

Conclusion

While many of the threats of our contemporary moment (right-wing nationalism, economic crisis) and the responses to them (solidarity, intersectional alliances) resemble the 1930s, in terms of style and affect the cultural expressions emerging from oppositional movements today could not be more different. For example, today, it is the right that is most invested in mobilizing national signifiers. Yet perhaps this past should not be abandoned too soon. The appearance of the John Brown Gun Club (in Kansas, Arizona, and elsewhere in the USA) under the auspices of the antifa network Redneck Revolt shows that radical history can still be usefully mined for contemporary struggles. If clearly combined with internationalism, a 1930s-style strategic nationalism might still provide a helpful model.

Another important difference between today and the 1930s is formal. Poetry has lost its privileged position as a popular, oppositional form. It is difficult to imagine a Neruda-like figure commanding the attention of thousands of miners at a rally today, as he could in Chile up until the 1970s. While we should not discount the continuing (though beleaguered) popularity of verse in parts of the world,5 the age of the poets is no more because the age of poetry is no more. Radical poets still exist of course (those associated with Commune Editions in Oakland are one example), but at least in the USA, today, the poetry produced by left-wing poets tends to be more academic, more milieu-based, and less portable beyond national borders than in the 1930s.

If poetry as a medium is no longer dominant, what else exists? Film and television, both industrial art forms requiring massive production teams and global distribution networks, cannot travel as cheaply or easily as poems. A quasi-leftist film like Black Panther (2018) can be screened all over the world (at the cost of entertaining a CIA-vision of internationalism), but a more hard-hitting and class-conscious film like Sorry To Bother You (2018) had difficulty gaining international distribution because its concerns, partially focused on racial politics in the USA, are thought to be too “specific.” If there are internationalist cultural forms today, they are even more ephemeral than in the 1930s. Memes, poster designs, slogans, images, and sometimes songs all crisscross the earth at record speed. Recent calls of solidarity—between Sudan and Algeria, Lebanon and Hong Kong, for example, or before that Palestine and Ferguson, or São Paulo and Gezi Park in Istanbul—show that the conjunction of certain place names that we saw in the listing/catalog technique of 1930s poetry can still have an affective charge. While cultural objects were produced out of these viral protest movements, they are surprisingly more nationally based. Hip-hop appears to have traveled most easily, but non-Anglophone examples (whether by the late Venezuelan musician Canserbero, Greek-Cypriot crew Social Waste, or French-Algerian rapper Médine) do not have the global reach one might expect. There are exceptions, like US rapper Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” (2018). The music video for this incisive critique of violence and racism in the USA gave rise to immediate responses from rappers abroad, who uploaded copycat videos with new lyrics onto YouTube with titles like “This Is Iraq” and “This Is Nigeria.” The Chilean feminist collective Las Tesis’ performance/intervention “Un violador en tu camino” enjoyed a similar viral internationalism.

Black writers can seek to unite blacks and whites in our country, not on the nebulous basis of an interracial meeting … but on the solid ground of the daily working class struggle to wipe out, now and forever, all the old inequalities of the past. (2002, 89)

This more practical approach to the issue of “love” is one way to get past the censors of a cultural dominant that is highly allergic to sentimentality and over-earnestness. Identificatory approaches to the suffering of others can have an affirmative role, as Lauren Berlant remarks: “Popular culture relies on keeping sacrosanct this aspect of sentimentality—that ‘underneath’ we are all alike” (2008, 100). While radical moderns were aware that search for what is common was predicated on not shying away from one’s enemies, today it is difficult not to read poetry centered on love—even if love as solidarity—as mawkish. “Our aesthetic categories,” as Sianne Ngai’s work demonstrates, are too precarious, ambivalent, and performance-based to rely on the centered subjective position of the 1930s radical modern (2015). The communist poetry of tomorrow—if there is to be such a thing—will have to be more collective, more steeped in negation, more feminist, and less amenable to narrow nationalist or multiculturalist recuperation, or it will not be at all.

Lest we treat our predecessors too unfairly, however, it is helpful to heed these admonishing words of Ritsos and remember that revolutionary culture is always produced within the limits of its own period: