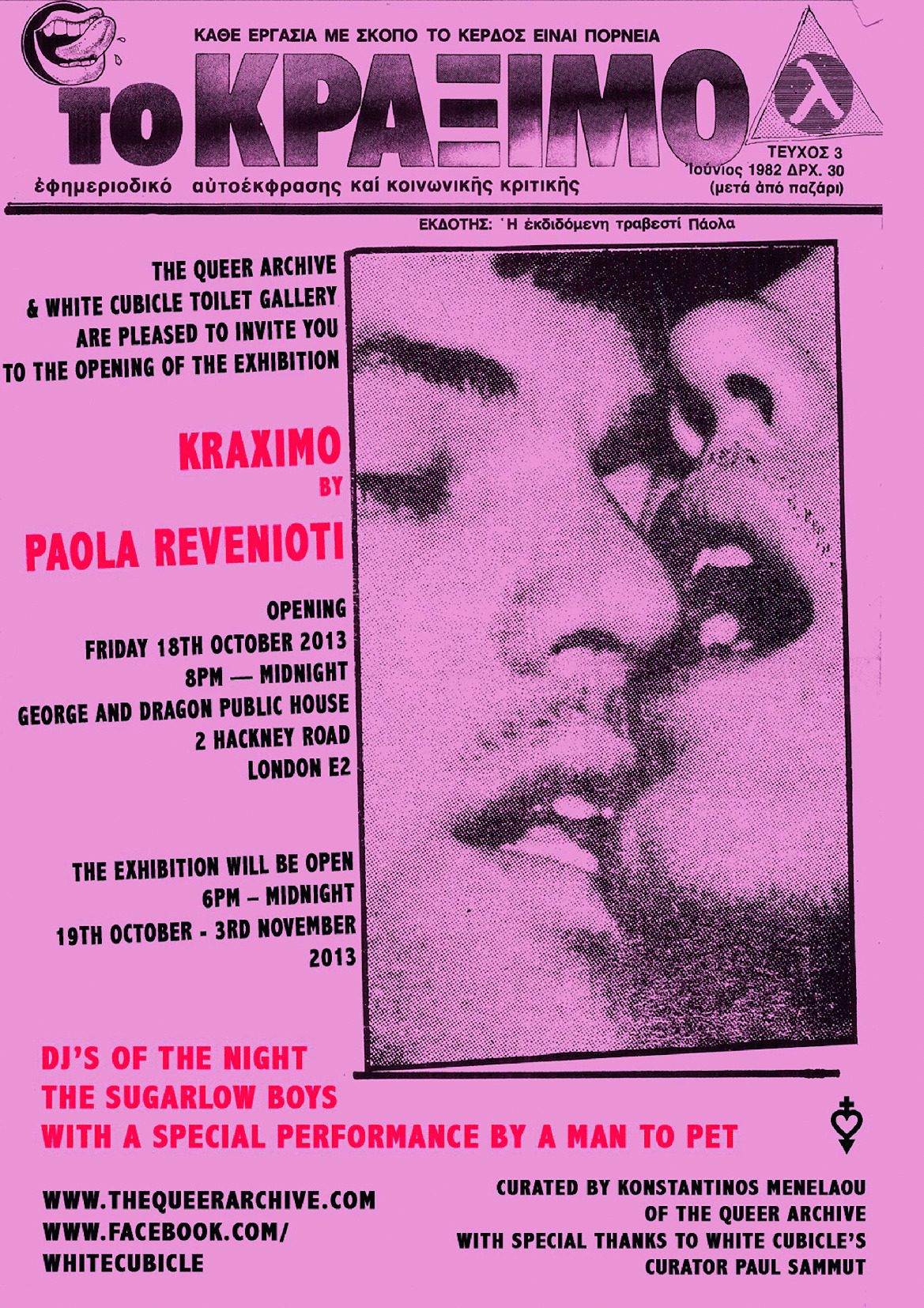

Poster for exhibition on Kraximo/Κράξιμο, Greek fanzine (2013). Image provided by courtesy of Paola Revenioti

The GSGE’s position is based on the belief that “offering the body for intercourse in exchange for financial remuneration […] should not be considered work, but instead, a form of violence degrading the female nature and dignity ‘as service’” (GSGE 2017). Prostitution, in other words, is characterized as inevitably causing harm to a woman’s very nature. Then, on February 27, 2018, the GSGE issued a second press release which equated prostitution with trafficking, stigmatizing prostitution by associating it with criminality and violence. This formulation resulted in the mobilization of the Greek Transgender Support Association. The Association, dedicated to protecting the rights of trans people in the sex industry, called attention to this sexist, misogynist narrative (GTSA 2018); treating sex workers not as citizens, but instead equating them with criminals, puts their lives in danger.

The issue of prostitution has become a common point of reference in feminist and democratic political action both inside and outside of Greece, and—in direct opposition to the stance taken by the GSGE—this action typically focuses on the client rather than the sex worker. Similarly, the contemporary Swedish model criminalizes prostitution by prosecuting the customer, and this model is recognized as an ideal European solution, including by the GSGE. But this model does not directly address violence against women. What motivates the connection drawn by the GSGE between the denial of sex work as work and the assertion that prostitution constitutions violence against women?

One can lose sight of how liberalism and neoliberalism are tied to gender and to prostitution specifically. In this chapter, I start from the laughable notion that (neo)liberalism is shocked by this vision of human exploitation. I suggest that even seemingly progressive policies, such as the Swedish model’s focus on prosecuting clients of sex workers, still reproduce a liberal myth about the uncontrollability of the dangerous human libido. Indeed, for the last four centuries at least, this myth has been at the core of a set of beliefs, which have in turn helped make possible bourgeois hegemonic control over the populace. That set of beliefs center on a scientific discourse that concluded that some people turn from sovereign to subordinate under the control of their libido, and, as a result, they live a (supposedly) sinful life and become dangerous for the rest of the society. Prostitution is part of the reproduction of this myth. The idea that there is an ethical/paranoid/dangerous libido is made into scientific truth.

Giorgio Agamben, through work by Karl Binding and Alfred Hoche, reminds us how the act of suicide was separated from the discourse of ethics and instead became an act within a legal discourse of rights. Thus, since “the law has no other option than to consider a living man as sovereign over his own existence” (Agamben 1998, 136), suicide became no longer a human rights issue. Neni Panourgia (2009, 111) explains how in the Greek context suicide was banned as a right for tortured exiles by the torturers in 1948. At stake, of course, is not just suicide, but exactly who has the right to “consider a living man as sovereign over his own existence”: the man or a “representative” of science and/or the state.

I draw inspiration from Panourgia and Agamben in my approach to prostitution. The regulation of the uncontrolled libido was a key site for defining a bourgeois understanding of human nature and the sources of social problems. At stake in debates over prostitution is thus much more than sex, violence, or work, but the legitimization of hegemony. The policies may change, but what persists is the fact that prostitution is about the regulation of sexuality and, through that, the distribution of power.

In the Greek government’s recent approach to prostitution, sex work is not recognized as work. But this is not due to some humanitarian perception that sex work is inhumane and thus cannot be work—capitalism operates in inhumane conditions. Moreover, prostitution emerged under the supervision of authorities in the early centuries of modernity, becoming a biopolitics of female subordination. Women were forced to turn to prostitution in response to a culture of rape in the fifteenth century (Federici 2004, 46–50). Historically, prostitution had three significant positive effects on capitalism. First, it naturalized male sexual violence, and it discredited lower-class women as a potential working population, following their public humiliation. Second, at a time when the bourgeoisie seemed to have lost control over the working populace after the black death (Federici 2004, 44), rape and prostitution broke the solidarity among the lower classes. Male violence, introduced in part via a legal regime that allowed rape and a biomedical discourse concerning a supposedly devilish female nature, broke down any potential class consciousness among the lower classes. Finally, it reinforced an understanding of human nature as driven by unreliable animal instincts.

Through this scientific interpretation of human instincts, the bourgeoisie accomplished something unique: it interpreted human poverty, prostitution, violence, and inequality as a consequence of a supposedly human criminal predisposition. That predisposition belonged to a conscious being, but one with a will that was subordinated to an unimaginably dangerous instinct. Ιt is telling that psychiatric and forensic texts after the Paris Commune explained that the upheaval started with prostitutes (Marinou 2015, 292), revealing the allegedly perverted character of the movement.

A quick review of the Great Confinement at the end of the seventeenth century also reveals the importance of this understanding of humanity’s dangerous instincts. As Foucault has demonstrated, the creation of the General Hospital in Paris—and then its replication in every major city in Europe—is central to the creation of a biopolitics of madness. What Foucault did not recognize is that, according to the scientific discourse of the era, insanity existed in vulnerable immoral beings such as women (Tzanaki 2018). It is with this backdrop that Salpêtrière, France’s largest hospital, was built in 1603 and converted in 1656 into an almshouse for elderly indigent women (Carrez 2008). As Carrez points out, by 1666, the Salpêtrière housed 2322 souls. In 1684, a new category of population was enclosed: lecherous women. In 1560, prisons were founded exclusively for courtesans in France, and finally, in 1684, this group was solely directed to Salpêtrière. In 1687, the King established a new edict: All women “living in sin” are to be enclosed in Salpêtrière as morally ill because of their acts: masturbation, cholera, eroticism, alcoholism, rape, and prostitution. This is the asylum, exclusively for women, and the largest of the three General Hospital’s asylums in population size, from which emerged the (supposedly) greatest discovery of psychiatry: the theory of psychic degeneration.

An entire literature unfolds from this moment about moral insanity and individual “fallacy.” Moral insanity (a psychiatric term indicating moral degeneration, which was introduced in 1801 and officially established in 1835) referred to people whose will was controlled by their libido and who were therefore dangerous to society and to themselves. This is how the liberal myth was constructed: Moral degenerates were those who failed to develop and remained at a stage of moral hermaphroditism and moral insanity, as the female part of human nature dominated the male. These people became subordinates to their libido; they were identified by reference to the circulation of sexually transmitted or venereal (αφροδίσια/aphrodisia) diseases. An allegedly abnormal population was therefore created.

This population comes to confirm in modernity what “aphrodisiac” morality has established since classical and Christian times. The ethics of aphrodisiac pleasures, as Foucault demonstrated, signified a code through which free Athenian males could guarantee their hegemony by their absolute right to truth/knowledge and power over the lower classes (women, slaves, children, and “effeminate men”). This code, which in reality was the truth/power of the hegemonic subject diffused through the aphrodisia/ethos to the entirety of society, emerged in European societies through the figure of the Forensic Aphrodite. It emerged as a subfield of Forensic Medicine in 1602, with a view to consolidate a regime of truth under the pretext of which juridical justice would conceal the illusion of a morally insane life. There is an obvious metonymic connection between the Forensic Aphrodite of the 1600s and the ethics of aphrodisiac pleasures from classical and Christian times. But this was the first time in human history that scientific expertise emerged as the source of absolute truth on the issues of pleasure (Kallikovas 1888, 12): the recognition of gender identity, sexual norms, moral paranoia; marriage, and whether a relationship is normal or abnormal; conditions of divorce; recognition of rape; and more. For the first time in human history, pleasures are defined as normal or abnormal by the scientific specialist.

In this context, what bothers capitalism with regard to workers and sex is, I argue, not the exchange of money for sex. What bothers the bourgeoisie is that “common women/men/intersex/intergender” adult beings dare to sell something that does not belong to the bourgeoisie: self-ownership of their lives. According to the discourse outlined above, sovereignty over their bodies, their sexuality, their will, their libido, their truth, and their consciousness belongs not to themselves, but to science and the modern state.

My argument is that European states are not really interested in protecting human life when they talk about and act on prostitution. The state has been intimately involved with facilitating prostitution from its inception. Brothels were created by states in the nineteenth century. Take an example from the Greek Kingdom at that time. After the Paris Commune, the Greek Kingdom was confronted with strikes and anarchist and communist publications circulated widely (Moskoff 1978, 162). Under the auspices of the Greek state, the public bordello of Vourla was built in the area of Drapetsona (on the north side of the inlet to the Port of Piraeus) (Lazos 2002, 97–99). Vourla, a building constructed according to Bentham’s Panopticon (Lazos 2002, 99), became the “topos” in which the Greek state was supposed to reform (and re-form) men’s libido. Vourla emerged as a “camp” designed to protect normal women from the animalistic nature of men’s libido. Apparently, in this camp, men were learning to control their sexual instincts toward women. Yet disobedient women were also driven to Vourla by force. Prostitution has never been apart from the force and violence of the state.

In that sense, the biopolitics of prostitution in liberal societies since 1602 presents a more complex picture than the contemporary governance of the sex industry suggests. Particularly, the question of what prostitution is finally all about demands to be rearticulated and re-addressed. It is from within this context that I present a twofold argument.

First, I provide a general description of the measures taken by the Greek state to combat prostitution during the interwar period, a pivotal point of the biopolitics of prostitution. Here, I present the “common woman” as having emerged as a source of liberal justification for patriarchal rule on the basis of an imaginary degenerate human psyche, instead of resulting from the relations of class struggle. This material reveals a link between the persecution of the prostitute and that of the communist: both are said to follow their libido. The interwar period in particular was thus a time for the consolidation of a discourse of sexuality in response to the “new woman” and the Marxist challenge, together.

Second, I explore how contemporary liberalism and neoliberalism claim sovereign power by fingering human nature/libido as the cause of crises, thereby obviating, politically as well as socially, the possibility of resistance to and revolution against capitalist injustice. The critical point is that this move places personal relations rather than capital relations at the center of the interpretation of social inequality and violence. There was continuity in this project afterward—as there was before, going back to the nineteenth century or earlier. But these discourses reappeared with particular force in the crisis of the 2010s, again as a response to crisis and left mobilization. Through this parallel, we can see how prostitution is made again an ideological tool for the consolidation of capitalist hegemony.

The Electra Complex

In 1922, the Greek state introduced Law 3032, “On measures against venereal disease and immoral women,” followed by the Royal Decree of 19/30-4-1923, which established “local committees and measures” to implement the law. This was not the first time that the Greek state attempted to take prostitution seriously. Earlier laws all centered on the authority of the municipal police to put an end to sexually transmitted diseases through the control of the κοινές γυναίκες (common women/prostitutes). But in 1922, for the first time, the law provided for state regulation of prostitution, and in particular the institutional recognition of the profession of prostitution, but in combination with their rigorous, regular, and systematic medical and criminal control. The 1922 Law also emerged during the same period when women, children, and nomadic populations in general were driven by force, by police and the bourgeoisie, to work for industry.

In reality, the state was called upon to control the masses, partly by applying the ideas of Cesare Lombroso, which permeated forensic and psychiatric texts of the time (Tzanaki 2018). Lombroso, an Italian criminologist and psychiatrist, and his son-in-law Guglielmo Ferrero, a historian and journalist, published La donna delinquente, la prostituta e la donna normale in the late 1800s (Lombroso and Ferrero 1896). The book was released in English under the title The Female Offender (1895) and in French as La femme criminelle et la prostituée (1896). The book recapitulated a core theory that Lombroso had developed in his previous book, The Human Criminal (1876, translated into Greek in 1925). There, Lombroso attempts to provide an explanation for human criminality by linking the insanity of the degenerate directly with the theory of atavism, “which claimed that women were on a lower rung of the evolutionary ladder than men” (Beccalossi 2012, 42). Although his work is less well known today, it constituted a milestone for the interpretation of criminality in its era, and although Lombroso’s first book was never translated into Greek, it had a major influence on the interpretation of the insanity and criminality of female homosexuality and prostitution (Vafas 1903, 339; Vlavianos 1906, 3–8; Tzanaki 2019). The book stood out as a fundamental guide to approaching criminality in manuals of the time.

In Greece, linking prostitution with criminality engendered a series of legislative measures intended to fight prostitution as a carrier of criminality and immorality. This was not, however, the first time that prostitution represented an imaginative barrier between the normal and the dangerous. Thanasis Lagios reminds us that in 1838, the French Academy of Sciences awarded the prize for best thesis to Honoré Antoine Frégier (1789–1860), chief of police at the Seine district. In his thesis, entitled Des classes dangereuses dans le population dans les grandes villes, Frégier marked as dangerous “the gamblers, the street-walkers, their lovers and their pimps, the madammes, the tramps, the mischief-makers, the scumbags, the petty thieves and the dealers,” and he suggested that work and the raising of salaries be plied as tools in the moral disciplining of this population. According to Lagios, this thesis is recognized as a pivotal moment in the Crime Classification Manual, the 1992 FBI Handbook that replaced the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in the “systematization and classification of offenders’ behavior” (Lagios 2013).

If prostitution was the primary feature of the criminal degenerate during the nineteenth century, for the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, the interpretation of prostitution at the beginning of the twentieth century was defined by the syndrome of Electra, as he proposed in his Theory of Psychoanalysis (Jung 1915, 69). According to Jung’s interpretation, the source of prostitution was located in the antagonistic relationship between the mother and the daughter over the love of the father. Similar to the Oedipal complex, the Electra complex reproduced the same problem according to which the “immoral woman,” the woman who is unable to mature, is fixated on this antagonism and consequently remains in a continuous infantilism-primitivism in constant pursuit of the father figure (Scott 2005, 8). What matters for our purposes is that, as elsewhere, in Jung’s theory, the “common woman” is conceptualized as embodying an abnormal femininity and furthermore, that she is understood as resulting from an imaginative “vulnerable” and “criminal” female self, from an unnatural perception of reality.

This construction echoes the liberal view identifying an innate, criminal human nature as the source of prostitution, violence, and insanity. The basic psychiatric and forensic worldviews of the time held that sloth, lust, and an excessive sexual drive motivated “common women” to participate in prostitution rather than remaining in poverty (Lombroso and Fererro 1896, 576). After all, degeneracy was, according to Lombroso, more than obvious in the supposed fact that “common women” could not procreate because they were morally degenerate, therefore infertile, and for that reason, free to work as prostitutes (Lombroso and Ferrero 1896, 525–535).

These ideas became widely accepted by Greek forensic medical experts such as Achilleas Georgrandas (1889), Georgios Vafas (1903), and Simonidis Vlavianos (1906) and the Greek psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Aggelos Doxas (who went by the pen name of Nikolaos Drakoulidis) (Tzanaki 2019). Drakoulidis, citing theories on prostitution by Lombroso, Havelock Ellis (1929), Pauline Tarnowski (1892), and Parent-Duchâtelet (1857), explained that “immoral women” turn to prostitution due to idleness and “a degenerative urge procured by a genetic perversion towards prostitution” present in the lower classes (Drakoulidis 1929, 11). By consequence, the “common woman” not only emerges as an immoral woman/populace but the idea is also linked to a scientific discourse that called for state involvement to control a disorderly and morally degenerate working-class subject. It was in this context that liberal intellectuals and bourgeois feminists concluded that prostitution was nothing but a psychological syndrome of an immoral paranoid being.

At this time, liberal feminists and intellectuals were systematically asking for the banning of prostitution, the closing down of all brothels, and the introduction of a commonly accepted code of “moral social conduct” for both sexes. From then on, the war against prostitution was presented as a moral duty of the democratic community of psychologically normal individuals, who were expected to fight against sexual passions, i.e., the sexually transmitted social, moral, and psychological diseases of abject subjects. Within this framework, the Greek state took a series of measures to tackle prostitution through the persecution of the “immoral woman.”

It was also during this period that the figure of the “New Woman” emerged in the public, demanding a place in society. These “new women” included female artists, writers, servants, workers, and actresses. They were placed at the center of violent persecution (Korasidou 2002, 81–90). It was a persecution that had as a point of departure a biomedical discourse that sustained the theory of this supposedly morally gynandrous/androgynous “New Woman” as a real danger of the social ethos (Nordau 1895, 1–34; Vlavianos 1903, 226–227). Likewise, experts in Greece concluded that prostitution arose among women of the theater and among those working in cafés and breweries (Vafas 1903, 369), but also those working as servants and maids and in general, those doing any work, without expert (i.e., bourgeois) moral guidance (Tzanaki 2019).

By the time Drakoulidis published his study, Gustave Le Bon’s Crowd Psychology (1896) had been published in Europe. This text, introduced in Greece mainly by Vlavianos, depicted a civilization that was coming closer and closer to hysteria, alcoholism, and suicide, due to the degenerate primitivism of the morally “effeminate” crowd (Tzanaki 2019). At the same time, scientific discourse by experts in forensic medicine, such as Vafas, and in psychiatry, such as Simon Apostolides, was formulating a moral normality of the bourgeois class centered around the non- or ab-normality of the lower classes as the source of violence, insanity, prostitution, criminality, disease, and death (Foucault 1987), especially in Greece.

As a direct result of psychiatric and forensic medical discourses, the language in the Greek law of 1836 refers to the κοινή γυναίκα (“common woman”) while that of 1922 refers to the ανήθικη γυναίκα (“immoral woman”). Furthermore, the decree of 1922 referred for the first time not only to ανήθικες (immoral) but also to ελευθέριες (free) women as prostitutes. The ελευθέριες was interpreted as the woman practicing prostitution occasionally, while the ανήθικη practiced it as a steady job. We must not forget that ελευθέριες in Greek refers to “freedoms” while the singular ελευθερία means freedom generally. The law here does not simply seek “a better approach and a more precise definition of the concept of prostitution, the role of the house of detention, and the categorization of immoral women,” as it is mentioned in the Greek literature (Mpelis 2018).

Instead, this decree comes precisely to stigmatize women’s claims to public space by declaring them prostitutes, particularly those of the lower classes. This division automatically made it much more difficult for women of the lower classes to move freely in specific parts of the city at specific times if they were not in the company of a male. This decree also shows the extent to which psychiatric and criminological theories and international conferences on this topic shaped juridical and legal processes that moved toward framing persecution around immorality and convinced the public about the danger of this internal other. This change in labeling was brought about in an effort to underline the psychic immorality that this type of woman hides deep inside. Immorality broke her will and drove her to sexual debauchery and criminality, thus exposing an entire society to the risk of sexual passions (Tzanaki 2018, 111).

This explains why the state convened a three-member committee called the “Committee for the Control of Venereal Diseases” (CCVD), staffed by the prefect, the police director, and a senior health officer. The committee aimed to control “immoral women,” but not men and to tackle sexually transmitted disease (Τzanaki 2018, 113–149). Indeed, through these committees, the state sought to secure the obedience of disobedient women. The ultimate purpose was obedience to a code of morality, which in fact underlined the sovereignty of the bourgeois and not the disease itself.

What remained distinctive were the numbers of its victims: when the Sygros Hospital allowed access for a census, out of the 1156 patients who were examined, only 49.2% (namely 559 patients) were actually treated for sexually transmitted diseases, specifically syphilis (Tsiamis et al. 2013, 32). During the International Conference on Prostitution in Rome in 1923, the League for the Rights of Women (the principal feminist coalition of the time) participated via Aura Theodoropoulou (its leading figure). While voting on the measures against syphilis, the Conference rejected as immoral the proposal to use condoms as a preventive measure. According to Theodoropoulou, “[t]he conference [of Rome] denounces the principle of sanitization [from venereal disease] with the use of condoms as it considers the method morally abject” (Tzanaki 2018, 133).

From the “Immoral Woman” to the “Immoral Communist”

The “immoral woman” emerged as a result of such forced relations, particularly after 1922, when Greek troops were badly defeated in war with Turkey, which was followed by an inflow of 1.25 million refugees, forcing the state to undertake immigration and population control. The catastrophe and refugee crisis brought Greece to the brink of a humanitarian disaster, and the aftermath showed the inhumane face of capitalism and imperialism. It is no coincidence that during the Interwar period, the bourgeoisie tried to interpret this crisis using libido as an interpretive tool.

In Greece, this process took place shortly after Freud’s publications on human psychoses and neuroses under the influence of the libido, which nests within the entire population during childhood; it later was settled through various publications into scientific certitude (Tzanaki 2019). It was via libido that the human will was put under the microscope of science and came under the jurisdiction of the civic state. Under these circumstances, common women, masturbators, anarchists, and so on would constitute the hazardous, degenerate Other. Particularly during the interwar period, with the Socialist Labour Party under Bolshevik influence in 1918 and its consequent renaming as the Greek Communist Party (KKE) in 1924, communist men and women were depicted by the bourgeois biomedical discourse, in particular sexologists such as Anna Katsigra, the first female lecturer at the medical school at the University of Athens, as a movement organized by “sexual paranoids.”

In this way, communism was narrowed down to a movement of beings who obeyed, as a result of their drives, their libido, the Party, and Russia. In other words, they obeyed a foreign commander, following their political/sentimental desire while ignoring and disputing national mandates. Additionally, the positioning of the Party itself that adopted the political slogan “for an independent Macedonia and Thrace” further justified the allegations of the liberal sovereign ideology of the time that these people actually suffered from moral paranoia under the influence of psychopathia sexualis (libido, instinct, or desire).

From the moment that any other idea outside the national imaginary and the claims of a manly/valiant patriotism was perceived as psychologically abnormal, the stigmatization of the communist man and woman as psychologically and mentally abnormal—and consequently dangerous to people and society—would gain more and more ground. This was particularly so when experts such as Katsigra argued that the communist ideology, defending self-sovereignty in sexuality, was the major cause of the spread of sexually transmitted disease among the population (Katsigra 1935; Tzanaki 2019). The meaning of the state of emergency was equal to the equation of the communist man or woman with the immoral, degenerate life of the prostitute that claimed self-determination and the right to have control over her work.

The communist was portrayed as immoral, psychologically ill, and a series of publications would underline the supposed debauchery and sexual orgies among communists, especially after 1924 and up to 1929. Law 4229/24 July with the new practice “idionymon” [ιδιώνυμο], introduced by the Venizelos administration, aimed to establish a new order centered around a well-disciplined society for its regulation against the “moral threat” of communism. These measures against the “social enemy” ultimately resulted in 3614 people being abducted, 232 imprisoned, and 334 exiled from 1921 to 1927 (Tsea 2017), while 16,500 communists were arrested between 1929 and 1936 (Kefallinou 2017). This new order would be adopted by the dictatorship of Metaxas through the Metaxas Emergency Law 117/September 1936, “regarding measures for protection against communism,” which called for imprisonment of at least three months and exile of up to six. This control was retained through the passage of the “health centers” that replaced the CCVD (Katsapis 2018, 154) under the Metaxas regime and with the aim, through the supposed control of sexually transmitted disease, to have a continuous access to the ethos of the lower classes. Finally, Law 1075 introduced the use of the infamous “certificates of proper social conduct” (πιστοποιητικών κοινωνικών φρονημάτων), a certificate of a social morality that was necessary for one’s life and mobility in Greece up until the post-dictatorship era.

This era is supposedly the period of a battle against immorality, but it is in fact marked by measures of biopolitics aimed at forcing human obedience. It is no coincidence that at this time institutions were emptied of prostitutes and replaced by communists. The history of the Empeirikeion Institution is indicative of this trajectory of persecution directed at both prostitutes and communists. The Empeirikeion, founded in 1917 (Korasidou 2002, 214), admitted girls who had been arrested for prostitution. The institution also served as a prison for male and female communists during World War II and throughout the Greek Civil War. During the 1950s and the 1970s, this institution was turned into the Female Penitentiary Institution of Athens. In a parallel and telling trajectory, Vourla, the public brothel opened in 1875, as I mentioned earlier, was closed right after World War II and was also turned into a prison for criminals and communists (Tzanaki 2019).

In this conflict between the liberal and the Marxist approach, it becomes clear why the “immoral woman,” disease, and prostitution itself suddenly became so important for bourgeois governmentality—not only during the interwar years but also today. If we ignore the historicity of this process, it is difficult to understand how liberal discourse achieved the societal consent necessary for the confinement of the prostitute and the communist, and how it camouflaged its moral reparatory pretenses even, as we will see in the following pages, in the persecution of a contemporary seropositive immigrant prostitute.

The Social Enemy Today: The “Immoral Effeminate Other”

With the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, the “immoral woman”—a free, even libertine woman—was described as thoughtless, absent-minded, corrupt, and dangerous (Petropoulos 1980, 33). A series of films sounded the alarm for society to take the necessary precautions against subjects who preferred to lead a rebellious and idle life and who practiced uncontrolled sexuality. In the legal arena, in 1960, Law 4095/1960 was implemented “for the protection from venereal disease and regulation of relevant cases,” once more promoting the persecution of supposedly dangerous “immoral women” and transgender sex workers; the legislation designated blacklisting, imprisonment, and/or exile for both categories (Ioannidis 2018; Papanikolaou 2015). Once again, under the pretext of controlling the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and the “immoral woman,” the persecution of persons allied with the communist philosophy and those who protested against the conditions of capitalism was intensified during the Cold War (Mpartziotas 1978).

In this context, the psychological profiling of the “immoral woman” as idle, non-reproductive, and disobedient, and at the same time excessively sexual, was projected as symptomatic of her criminal inclinations. Katsapis, who examined the archives of the “Ethics Commission and the General Archives of the State” from 1940 to 1971, revealed that in numerous prosecutions of women, it was not the act itself but rather “the ‘corrupt nature of her personality’ that had been under scrutiny” (2018, 152). Over the next few decades, the preoccupation with sexually transmitted disease returned to the scene with the AIDS epidemic becoming the paradigmatic space where illness was said to rule over the lives of those who fell victim to their libido/desires. Moreover, the “immoral other” that spread illnesses such as AIDS (Giannakopoulos 1998) was seen as wielding a power which threatened the entire society (Maki 2015).

In 1981, the Social Democratic Panhellenic Socialist Party (PASOK) came to power. Despite implementing a series of measures regarding the democratization of family law toward more equal gender relations, the socialist party orchestrated a fierce campaign against prostitution by introducing Law 1193/1981, “on the protection from venereal disease and the regulation of related issues,” which targeted spaces of homosexual sociality. In the following years, the growing crisis of capitalism, combined with the aggravation of social problems and poverty in Greece, gave rise to projects that aimed to restructure the neoliberal image, giving way to the emergence of racist, sexist, and homophobic discourses, of the extermination of the imaginary internal immoral enemy.

Among the developments of the contemporary era, the most publicized was the police raid orchestrated by the Minister for Health and Social Solidarity Andreas Loverdos in 2012. Faced with the “terrifying possibility of an electoral victory for the Left” (Athanasiou 2012) during the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, an entire state mechanism turned against the “criminal” migrant female sex worker. Shortly before the 2012 elections, in an effort to reverse the outcome, Loverdos and the Minister of Citizen Protection Michalis Chrisochoidis, at that time, implemented Health Regulation 39a/2012 “to restrict the spread of infectious diseases.” Loverdos and Chrisochoidis implicitly attacked (supposedly) undocumented migrant women who mainly came from Africa and practiced sex work. The main argument was that they were aware of their seropositivity and thus consciously risked the transmission of HIV to “decent family men” (Athanasiou 2012).

In reality, those women who were HIV-positive were mainly of Greek origin (with one exception). Nevertheless, the supposed danger of HIV served as reason for their photos to be publicly posted. Given that seropositivity was equated with immorality, sex work, homosexuality, illness, and death, they were represented as a threat to the nation, imprisoned and publicly humiliated. Despite their acquittal, they remained in police custody for up to eight months. Subsequent suicides by some of them following their release show clearly the outlines and effects of a neoliberal regime bent on manipulating the myth of the imaginary immoral dangerous other, for the sake of alleviating capitalism’s instabilities, particularly during times of crisis. Those women were depicted as not only being aware of their “illness,” although most of them were actually not ill, but having the selfish intention to destroy the Greek family through prostitution. Here, as in the 1920s, the nation was called to unite against a social/immoral/contagious threat.

The pivotal point that we are witnessing today in a period characterized by a political, social, and economic human crisis, just as we glimpsed during the interwar years, is the expanded sexist and increasingly racist involvement of the neoliberal state in all sectors of human life. That was the point that Paola Revenioti, a Greek transgender activist, had already made clear in the 1980s from within the pages of Kraximo/Κράξιμο, the fanzine she published from 1981 until 1993. The publication’s expenses were covered almost exclusively from her savings from clients for twelve consecutive years, as she has repeatedly emphasized. Echoing clearly Marx’s phrase “Prostitution is only a specific expression of the general prostitution of the laborer” (Marx 1964, 100), the fanzine repeated in almost each issue the sentence “any form of work aimed at profit is prostitution” (Revenioti 1981). In this way, Revenioti places the value of labor and the concept of the exploitation of life and sexuality by capitalism itself at the center of the discussion (Marx 1964, 19; 2006; Milios et al. 2005).

This was also underlined by the anarchist Emma Goldman in 1910, when, in her essay “The Traffic in Women,” she argued that all resistance and protest actions should address not individuals but the exploitation of human life and sexuality by capitalism (Goldman 1910 [2002], 3). The essay was written in response to the actions and legislative measures against white slavery of that era.

Thus, to return to the beginning of this chapter, rather than seeing the Greek GSGE’s 2017 committee as a form of power that produces protection, I read it as an exclusionary form of governmentality that reproduces the norms of power, knowledge, and government (Foucault 2007, 30). Here I think, it helps us to see how prostitution served the state, from the interwar period until today, to apply the rules of sovereignty over brains and psyches, by policing a supposedly scientific libido, producing and managing life, and ultimately deciding on its value. That is what exterminates the right of human life to sovereignty over one’s own life.

This shaped the ideology of the final composition of the GSGE’s committee. The team largely consisted of lawyers, prosecutors, specialist ministry counselors, a police officer, a forensic psychologist, and a judicial psychologist (GSGE 2017), without a representative for the workers in the sex industry. This exclusion of sex workers from that project management team is not only unnecessary and demeaning but is indicative of a certain logic. It illustrates how prostitution continues to be understood by officials as causing severe harm to human nature, jeopardizing psychological integrity, and transforming sex workers into morally degenerate beings incapable of deciding for themselves. This continuity is what links the interwar years with the contemporary flourishing of new forms of power. Τhe only way to combat this discourse (Merteuil 2019) is to dare to negotiate its conditions by placing the critique of capitalism itself at the center of our analysis, rather than blaming human beings and impeding their right to self-determination.