Silkscreen by Vera Bock [between 1939 and 1941] as WPA federal art project

Often, debate over the appropriateness of the comparison seems to displace suffering and fear in the present. But some of our most fundamental concepts—of change, progress, agency, economy, democracy—do seem to be in play. It is worth recalling that at the beginning of the twenty-first century, received opinion held that the future belonged to liberal democracy and that monetary policy had forever tamed the business cycle—both variants of a linear, progressive telling of history that has arguably been the predominant temporal consciousness of capitalist modernity. Against this, the suggestion that the past has in some sense returned (or that we have returned to the past) is inherently unsettling—yet possibly also galvanizing, as Walter Benjamin (1968, 253–264) claimed, writing at the brink of death at the end of the cataclysmic 1930s. A sudden curve in what seemed a straight road brings promise as well as danger.

The essays in this volume take on the question of what we might learn by holding the interwar period and the contemporary moment up to each other, while remaining attentive to the complexities and nuances of both. This approach sets the contributions of this book apart from the increasingly commonplace comparisons between these periods. In line with the standard division of intellectual labor and habits of thought, most approaches isolate economics from politics, taking up either the comparison of the Great Recession and the Great Depression or that of contemporary right-wing populism and interwar fascism. No secret that such a separation of politics from economics, whether analytical artifice or ideological maneuver, renders the economy politically neutral and the political process innocent of class and money power. Indeed, thinking through crises of economics and politics separately facilitates their tractability within reigning liberal capitalist histories, epistemologies, and policy frameworks. Reduced to two-dimensional caricatures or presented as abstract logics that can be extracted from their respective moments, financial crisis and fascist politics can seemingly be avoided through sensible policies and a recommitment to liberal ideals and institutions. As if the political system can be expected to act in the general interest to contain economic disaster, while the crisis of liberal democracy can be addressed without confronting capitalism’s systemic inequalities.

The contributors to this volume are attentive to the lessons to be gained from seeing crises of capitalism and liberalism as aspects of a common historical process. “If you don’t want to talk about capitalism,” Horkheimer famously wrote in 1939, “then you had better keep quiet about fascism” (cited by Gandesha, this volume). Importantly, as a group, they also consider the economic and the political together with the social and the cultural, including the dynamics of social reproduction—of race, gender, and generation—at the heart of both the micropolitics of everyday interaction and the systemic contours of domination. The particular approaches taken, and problems emphasized, are diverse and varied. The chapters that follow offer up histories of ideas, structural analysis and critique, and national and regional case studies. They feature topics that do not often appear in predominant discourse on the two periods, from prostitution to poetry , as well as geographical areas that are often left out of the comparative frame, such as Latin America and East Asia. They are also flexible in terms of periodization. The “1930s” in our title can be taken literally or as a convenient synecdoche for the interwar period, or even for a longer period of “systemic chaos” (e.g., Arrighi 2010), depending on the national and regional context, empirical focus, and analytical approach. The contemporary moment is similarly open to distinct temporal interpretations. The effort is, not to put too fine a point on it, a “timely” one, for the goal is less the parsing of years than the simultaneous mobilization and interrogation of timeliness as it manifests in historical comparison.

Comparative Structures: Homogeneity, Continuity, Repetition

In fact, the question of the relationship of the 1930s to our contemporary moment again raises fundamental questions of how we understand the structure of temporal comparison, indeed the very relationship of “structure” to “event” (see, e.g., Koselleck 1985; Roitman 2013). The presentism that predominates in social science (and in capitalist modernity generally) arguably assumes the question away; the present is either entirely distinct or all time is “homogeneous and empty,” as Benjamin famously put it (1968, 261). Many discussions of the contemporary moment in light of the 1930s follow this temporal framework: The past may be an explanatory resource, a source of lessons that can be imported into the present, but there is no organic relationship between these moments. As if financial crises, authoritarian populisms, and genocidal xenophobia, were simply things that happen from time to time.

The essays in this volume move in different analytical directions. One of these directions—a second approach to comparison—is to outline a temporal structure of historical regimes or institutional configurations that knit together a panoply of political, economic, social, and cultural processes across time. Some of the structures considered go back much further than the 1930s: capitalism, colonialism, racism, patriarchy. Nevertheless, for most of our authors, the 1930s (or the interwar period) was a pivotal moment in the unfolding of the longue durée, as well as for the emergence of regimes and institutions, even if these expressed enduring relations and imperatives. This includes, of course, historical fascism, which, despite being essentially destroyed as a regime by the end of the Second World War, nevertheless left important residues behind (see, e.g., Finchelstein 2017). It also includes that form of capitalist regulation known as “Fordism” or “embedded liberalism” that emerged out of the crisis (Aglietta 2001; McDonough et al. 2010). Much of that institutional order is still with us, despite the transition to a neoliberal regime after the 1970s. There are of course other forms of periodization possible: for now, it is enough to note that many of our authors deploy a temporal structure of systemic continuities, albeit with points of inflection, transition, or mutation.

A third temporal structure that appears here is the cycle, a repeated sequence of events that occur as part of an ongoing processes: for example, “long waves” that pass from a surge of development to financial expansion and crisis (Arrighi 2010; Perez 2003; Roberts 2016; Shaikh 2016). Here, the interwar period and the contemporary moment are typically presented as homologous moments of economic stagnation and chaos. This cyclical temporal structure arguably provides some of the most provocative, far-reaching, and internally coherent explanations for the similarities between these two periods, and is utilized to effect by several of the authors collected here. However, this approach is also sometimes prone to sliding into a rigid, overly mechanical view of history as repetition. (It is also worth noting that for the most part, this cyclical temporality has been applied to the economic processes of capital accumulation and crisis, and much less to the resurgence of illiberal nationalisms.)2

In the rest of this introductory chapter, we will briefly consider how comparison between the 1930s and the present often appears, and the work done by that comparison. As we have suggested, these comparisons typically take up either the economic or the political, and we will follow that general division in the following discussion, setting the stage for the more synthetic analyses carried out by the chapters that follow.

The Great Depression and the Great Recession

The Great Recession was from early on recognized as an event similar in kind to the Great Depression, most notably by the central bankers and others tasked with responding to the crisis (Eichengreen 2016; Tooze 2018). Both involved an initial recessionary movement followed by a rapidly unfolding financial crisis, which included precipitous falls in asset prices, a wave of defaults and the collapse of financial institutions. Both were global in scale, although unevenly so (even this unevenness, however, showed striking similarities, with epicenters in the United States and Europe, and more attenuated impacts on Asia, Latin America, and Africa). And both crises were characterized by dramatic declines in output and increases in unemployment, which led to a long period of stagnation or slow recovery beset by additional crises. This sustained reduction of world output suggests that the “Great Recession” was really the first global depression of the twenty-first century, even if it was not as deep as the Great Depression of the 1930s (see Krugman 2013; Roberts 2016; Shaikh 2016).

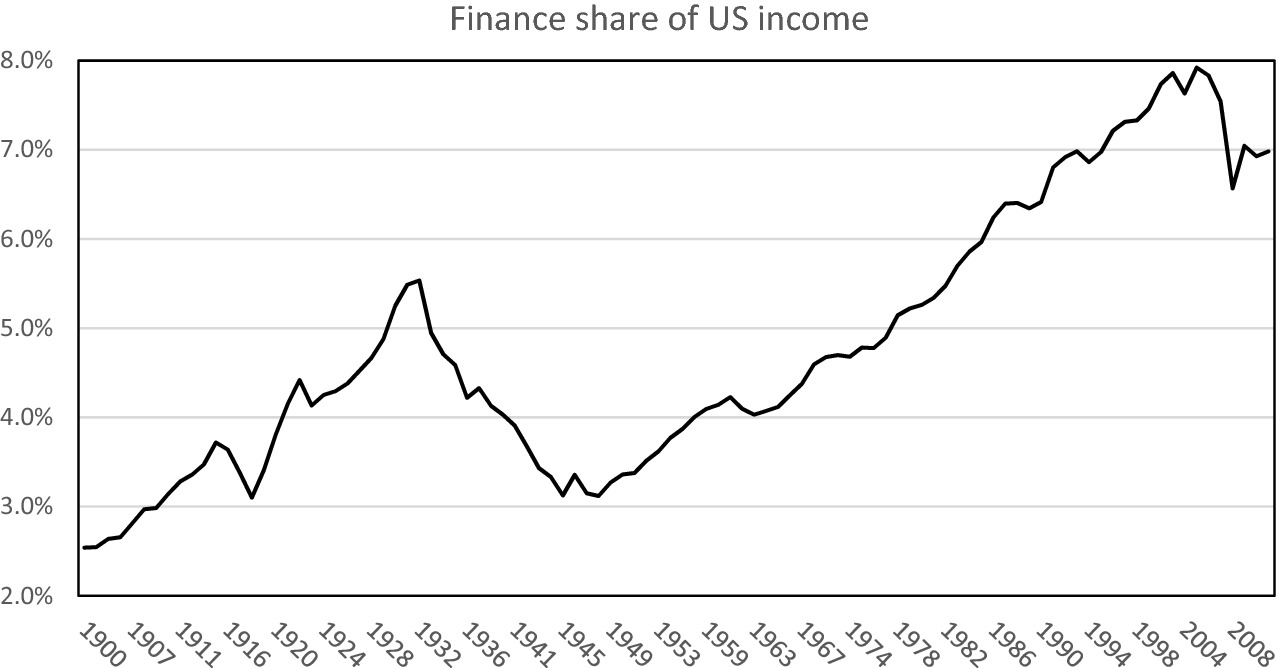

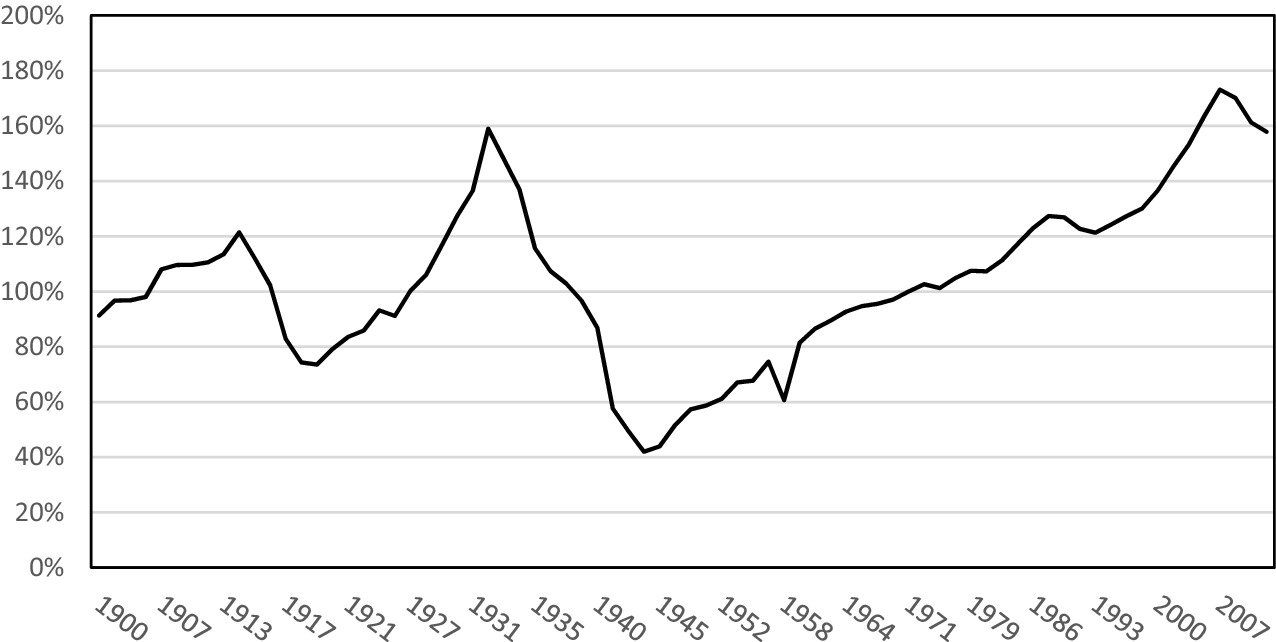

Less obviously, both crises were preceded by similar processes of financialization and rising inequality. The turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were both periods of financialization at a global scale—the emergence of new forms of finance, expansion of the role of finance in capitalist accumulation, increased indebtedness by firms, households, and states, and the formation of a series of speculative bubbles in housing, stocks, and other assets (see Eichengreen 2016; Fasianos et al. 2018; Lapavitsas 2013). The increase in inequality is also notable, particularly in the United States—epicenter of both crises—where measures of inequality, on a steep ascent from the 1980s, had reached levels not seen since the 1920s by the beginning of the twenty-first century (Kumhof et al. 2015; Stockhammer 2013).

Responding to the Great Recession: Historical Memory and Political Economy

At the outset, all indicators suggested that the Great Recession was on track to rival or outdo the Great Depression (Almunia et al. 2010). The financial system of the early twenty-first century was deeply integrated and dependent on short-term credit, which made it vulnerable to rapid contagion and collapse (Tooze 2018). If the Great Recession did not produce a collapse of the magnitude of the Great Depression, it was largely because of institutions and lessons inherited from the 1930s. This time, dramatic measures were taken—at great public expense—to prevent the collapse of the banking system. Money creation was no longer bound by the “golden thread” that hampered central banks at the beginning of the 1930s (Eichengreen 2016; Polanyi 2001), although the Euro played a similarly pernicious role of blocking effective monetary response to national conditions. In some places, social safety nets established after the 1930s also provided “automatic stabilizers” to sustain demand and livelihoods, although ultimately, the tendency was to undermine these institutions (through austerity regimes) rather than to bolster them.

In short, the lessons learned from the 1930s and applied to the first depression of the twenty-first century ended up being deeply one-sided. While the banks were rescued and interest rates cut, public investment and direct contributions to workers’ livelihoods were sidelined. Stimulus spending was weak and limited to only a few years and a few cases (the United States, China, and some others). Most glaringly, banks were bailed out at enormous public expense, while little or nothing was done for indebted households. The most affected Eurozone countries were saddled with debts from the bank bailout and, unable to employ monetary policy, were forced to endure years of austerity and “internal devaluation” (above all, wage decreases).3

While the example of the Great Depression certainly informed responses to the crisis, organized class interests articulated within a geography of uneven development were decisive. A heavily financialized capitalist class could agree on the necessity of rescuing itself from collapse. But finance capital fears inflation, which reduces the value of debts, while capitalist interests in general feared an expansion of the welfare state, public employment, and the bargaining power of workers. These interests militated successfully against the employment of the fiscal and often even the monetary lessons of the Great Depression.

They were aided in that there was little popular narrative around depressions and how to deal with them. The Fordist common sense that emerged from the Great Depression—for example, that workers had to earn enough to buy the fruits of industry—had been eroded by a generation of neoliberalism and globalization. Advocates of austerity were able to appeal to a different common sense of household economics, where there is no paradox of thrift in hard times, in contrast to macroeconomic reasoning after Keynes. They also mobilized the guilt and ethics of obligation that glom onto debt—fueled by strong doses of racism and nationalism—to create compelling austerity narratives, attributing the crisis to allegedly irresponsible spendthrift nation-states (such as Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, or Spain—the so-called PIIGS) or, for the US right, government profligacy in the service of supposedly irresponsible, financially illiterate homebuyers. The role of neoliberal policies in generating the crisis was obscured, and widespread outrage at the bankers and bailouts was deflected (see, e.g., Mylonas 2019).

The lessons and institutions of the 1930s were, then, applied just enough to maintain the coherence of the financial system, and the financialized system of accumulation that had prevailed before the crisis. This brings us to a major point of difference between these two historical moments. The Great Depression led, at least momentarily, to a reduction in the financialization that preceded it. By the end of the Second World War, a distinct regime of “embedded liberalism” (or Fordist accumulation) would be established. In contrast, no such changes have yet emerged from the first depression of the twenty-first century. The very effectiveness in staving off a full financial collapse this time around has also arguably prevented a fuller reckoning with the financialized, neoliberal regime that produced it. Among other things, this raises the specter of a repeat performance.

Explaining the Recurrence of Crisis: Finance and Debt, Innovation and Inequality

Within mainstream economics, there was some serious reckoning with the limitations of the neoliberal monetarist paradigm that prevailed before the crisis, given the inability of monetary policy to stimulate investment even at zero (or negative) interest rates. This rethinking involved another look at the Great Depression, and, in particular, the role of indebtedness by households and firms in setting the stage for both crises, based in the largely neglected works of Irving Fischer and Hyman Minsky. (Notably, one of the major figures in this historical reassessment was Ben Bernanke, the chair of the US Federal Reserve, who was also responsible for the innovative response of “quantitative easing.”) In this analysis, both crises were caused by processes of “debt-deflation” and deleveraging in the wake of speculative bubbles: a decrease in asset prices (or deflation) increases the burden of debts, constraining the debtors and leading to retrenchment by banks, while lending, investment, and consumption grind to a halt. Although the mechanism of the crisis is somewhat distinct, many of the conclusions are essentially Keynesian: Lower interest rates will not induce investment, so that either aggressive monetary policy (e.g., “quantitative easing”) or public spending is needed to reflate asset prices and create demand (Eggertsson and Krugman 2012).

Beyond the question of effective regulation, however, Minsky saw the creation of increasingly unsustainable debts as a regular cyclical feature of capitalism, as the memory of prior collapses fades and both borrowers and lenders adopt increasingly irrational expectations of future growth. Palley (2011) has developed this process into a kind of meta-Minsky cycle, in which regulations on speculative finance are steadily reduced and increasingly evaded, setting the stage for larger and deeper crises over time. The discourse that monetary policy had tamed capitalism’s crisis tendencies therefore becomes part of a cultural process enabling the return of crisis.

What’s more, both crises were preceded not only by an increase in debt, but also by a series of speculative bubbles in assets of all kinds, from stocks to real estate, and, in the recent period, futures, derivatives, and other more exotic assets. Both crises were thus preceded by the accumulation of large pools of wealth seeking outlets for investment, outside of the simple reinvestment in existing firms and lines of production, what Bernanke referred to in 2005 as a “global savings glut.” A fundamental question that emerges here is this: Why was there so much money available to finance the growth of consumer indebtedness and investment in speculative assets? Several sources have been indicated for this “glut”: The low interest rates maintained by the US Federal Reserve and other core central banks; the growth of savings in Asia; China’s attempts to avoid currency appreciation; the need to hold hard currency reserves as hedges against speculative capital flows; and more. While many of these may be particular to the monetary and regulatory order of the late twentieth century, a comparison to conditions of the early twentieth century suggests that the accumulation of surplus capital might be a perennial or cyclical aspect of capitalism.

Writing the History of Capitalism : Waves, Cycles, and Stages

A class of thinkers, influenced in various degrees by Schumpeter and by the classical economists, from Smith to Marx, sees both crises as outcomes of longer cycles, waves, or stages in the capitalist economy. These are generally understood to be rooted in more fundamental processes of innovation, investment, and profitability, and related to broader processes of institutional, political and social or cultural change. For precisely this reason, they constitute potentially more productive, albeit more challenging, bases for interpretation of the relationship between contemporary events and those of the 1930s.

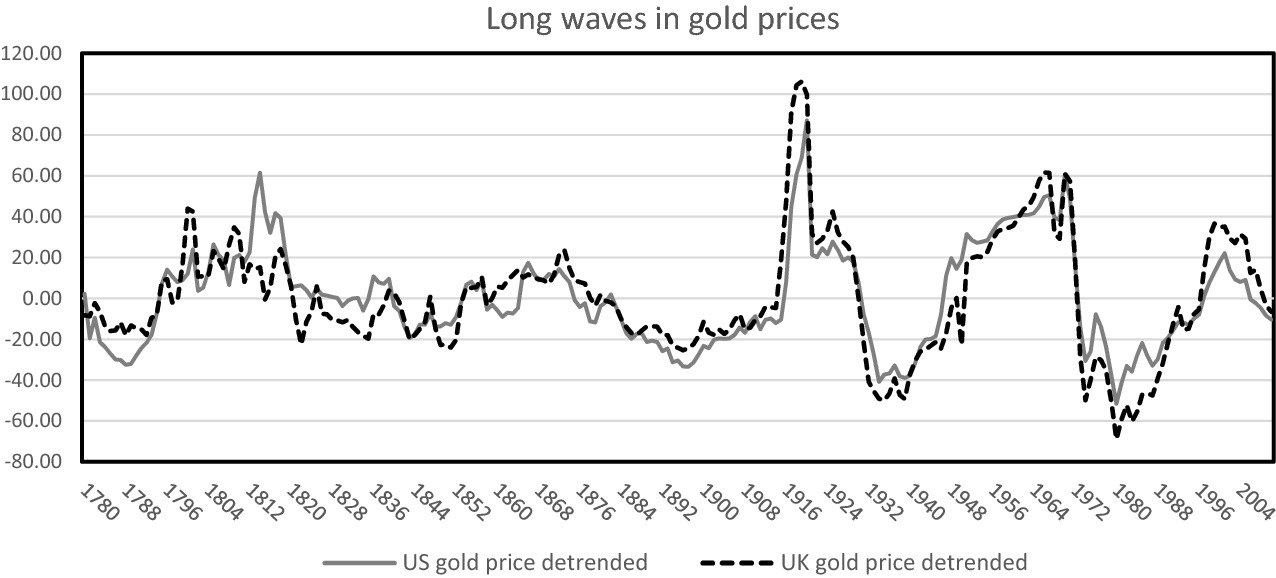

Long waves as fluctuations in gold prices (1780–2010), with trend line removed

(Source Data and analysis from Shaikh [2016, 726–728, database at http://realecon.org/data/])

One basic feature of all wave theories is that capitalist accumulation is discontinuous and to some degree self-limiting by nature: the very dynamics of expansion lead to a subsequent period of decline, usually rooted in a declining rate of profit. Perez (2003) and Arrighi (2010), for example, argue for a conceptualization in terms of s-shaped curves rather than waves; “great surges of development” (Perez 2003) followed by a period of stagnation. In these and most other recent accounts, this second moment, the low part of the wave or the flat top of the s-curve, is also understood to produce a process of financialization, as capital withdraws from production (where profits are declining) to pursue profits through some combination of financial mediation, speculation, and debt-extraction. One analytical strength of these perspectives is that they provide explanations for the recurring phenomena of financialization and crises in capitalism.

The more specific accounts of cycles of accumulation vary according to the analyst’s understanding of how capitalist accumulation works and why it is that profits tend to decrease following a wave of development. Some “orthodox” Marxists point to a “rising organic composition of capital,” or a declining proportion of living labor in production (e.g., Roberts 2016), while Anwar Shaikh (2016) presents a sophisticated alternative based in “real competition.” A simpler argument is that profits are higher in new branches of commerce or industry and are subsequently reduced as more competitors enter existing lines of production. This argument, originally advanced by Adam Smith, is important to the Schumpeterian tradition as well as various Marxian schools (Arrighi 2010, 228; e.g., Brenner 2006). In these accounts, technological or organizational innovations have an important role opening up new lines of development.

Carlota Perez (2003) has proposed a Schumpeterian theory of cycles created by the interaction between technological inventions, finance capital, and the transformation of economic institutions, which is employed in Rayner’s chapter in this volume. In brief, major new technologies provide the basis for a “surge of development,” but this potential can only be realized through widespread changes in business organization, finance, regulation, and the creation of new infrastructures, which together make up a “techno-economic paradigm.” The creation of a new techno-economic paradigm is a disruptive process that passes through “eruption,” financial speculation, dislocation of existing industries, uncertainty and crisis, against the backdrop of exhaustion of opportunities for investment in the industries of the prior wave.

The Great Depression and the Great Recession are therefore understood in terms of the emergence of two techno-economic paradigms: mass production and the automobile, after 1900, and information and communications technologies (ICTs), after 1971. The financialization that preceded both the Great Depression and the Great Recession was, then, an analogous stage of “frenzy,” as finance speculated on the potential of these new technologies—a thesis which does help to make sense of the irrational exuberance of investors leading up to the “Minksy moments” of the 1920s and 2000s. The crises that follow the frenzy express the inability of the existing system to assimilate these new technologies, but are also “turning points” that clear the way for the consolidation of the emergent techno-economic paradigm; in the case of the Great Depression, the mass production and automobilization that sustained the postwar boom. The Great Recession, Perez suggests, should be another such turning point, that would make way for the full exploitation of the potential of ICTs. By her own account, however, this development would seem to require significant institutional changes and infrastructural investments, a kind of global Green New Deal (see, e.g., 2013).

For Giovanni Arrighi (2010), the “systemic cycles of accumulation” are more profoundly political processes, intimately linked to the rise and fall of hegemonic world powers. For Arrighi, “financial expansions” also occur as a result of the exhaustion of possibilities for profitable investment in existing lines of production, but they are fundamentally characterized by the exploitation of rivalries between states—rivalries driven by the same intensification of competition that caused capital to flee production in the first place—through the cultivation of public debts and military spending. Financialization is therefore closely linked to “systemic chaos,” characterized by conflict between capitalist states, financial expansion and speculation, stagnation and crises. Out of crisis and war, a new hegemonic power eventually emerges to organize a new systemic cycle of accumulation, based on the employment of new forms of organization of finance and production. Rayner, Buscema, and Jung each employ this paradigm in their respective chapters.

The Great Depression and the Great Recession in three cyclical theories

Kondratieff waves; “standard” version | Perez’s great surges of development | Arrighi’s systemic cycles of accumulation (SCA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

1910–1929 | Downswing | Maturity of steel and heavy engineering; irruption and frenzy of mass production | Financial expansion and systemic chaos (beginning 1870) |

1930s | Trough | Transition from heavy engineering to mass production paradigm | Terminal crisis of British-led SCA |

1945–1970 | Upswing | Synergy (expansion) of mass production | Material expansion of US SCA |

1970–2007 | Downswing | Maturity of mass production; irruption and frenzy of ICT | Financial expansion and systemic chaos |

2008– | Trough | Transition to full development of ICT? | Terminal crisis of US SCA? |

Other understandings of cycles begin from the broader political and institutional or cultural matrix in which capitalist accumulation occurs, rather than locating cycles in dynamics internal to the accumulation process. Karl Polanyi (2001) famously argued that capitalism was driven by a contradictory “double movement”: on the one hand, a push to treat everything as a commodity, and on the other, a counter-movement to protect “society” from the crises which inevitably follows commodification of land, labor, and money. Polanyi considered the crisis of the 1930s in these terms, as a global movement toward social protection in response to the crisis provoked by excessive commodification (even if it often came in the “suicidal” form of fascism). The neoliberal era, which he did not live to see, has often been understood as a move back to dis-embedding of markets, which was, predictably from this point of view, followed by crisis. Although a counter-movement to re-embed the market is at best incipient, contemporary “populist” movements can be interpreted in this framework, as Polanyi interpreted fascism in his day (see below). There would also seem to be potential for a synthesis between this Polanyian cyclical account and the meta-Minksy cycle proposed by Palley: put simply, there is a tendency toward collective forgetting of the dangers of liberalization, abetting the drive toward dis-embedding.

Polanyi’s argument shares much in common with the subsequent “regulation” and “socialstructure of accumulation” schools (e.g., Aglietta 2001; McDonough et al. 2010), which also present theories of capitalist crises and transitions that do not depend on a single mechanism internal to the accumulation process: Rather, capitalism is understood to be characterized by multiple contradictions whose relative weight changes over time (see also Harvey 2007, 2014), and which are only partially and temporarily resolved by a given institutional and regulatory order. For these theories, too, crises play a central role, by demanding the creation of new institutional orders: crises in the 1930s and the 1970s led to the creation of Fordism and neoliberalism, respectively, and many expected the crisis of the 2010s to have a similar transformative impact, although again, it is not clear that it has. While these theories are appealingly open to transformation and contingency, they may be less equipped to deal with the regular features, sequences (or even periodicity) of capitalist crises.

Looking Ahead: Another Surge on the Horizon?

Albeit in distinct ways, most cyclical theories suggest that the Great Depression somehow set the stage for the postwar “golden age” of capitalism. The intriguing—albeit still unanswerable—question that follows is if the Great Recession will also lead to a “great surge of development.” While cyclical theories often seem to imply that development follows depression as a matter of course, the repetition of past sequences cannot be assumed. More convincingly, they may indicate the necessary conditions for a new round of sustained accumulation—and in that respect, most of the analyses presented here suggest that conditions for a new surge of development have not been met. If massive devaluation is necessary to clear out the overhang of underperforming investments, as some Marxian and Schumpeterian theories suggest, then the relative effectiveness of interventions to limit the crisis may have prevented a needed renewal. There are also few signs of the kinds of widespread institutional changes and infrastructural investments that would auger a new regime of accumulation or techno-economic paradigm: we are still limping along on the back of a zombie neoliberalism.

The conclusions offered by cyclical theories of capitalism may therefore coincide with noncyclical arguments for “secular stagnation.” Interestingly, secular stagnation theories were widespread in the 1930s, and their renewed popularity today—including among solidly mainstream economists such as Larry Summers and Robert Gordon—is another point of historical convergence, although many fewer today consider that a future of stagnation means the end of capitalism.

The reasons provided for secular stagnation are diverse. There are technological arguments: in comparison with the automobile, suburbanization, and mass production industries of the capitalist golden age, the current technological mix does not seem to provide as many opportunities for complementary investments in an expansive frontier of consumer goods, nor does it promise an expansion of mass employment that would help to guarantee dynamic demand: in fact, there are fears that it will displace more jobs than it creates (see, e.g., Frey and Osborne 2017).

Others point to slowing population growth and aging populations (Gordon 2016); monopoly capital and its surplus disposable problem (Baran and Sweezy 1966; Foster and McChesney 2017), a secular (rather than cyclical) trend toward a rising organic composition of capital, or simply the ever-increasing difficulty of maintaining infinite compound growth (Harvey 2014). Piketty (2014) argues that it was the postwar period that was exceptional (partly because of the massive destruction of wealth between 1914 and 1945); the historical standard is much slower growth and a tendency toward the concentration of wealth.

Finally, of course, there are the manifest ecological and planetary limits, which, if they have not already contributed to stagnation, must at some point (soon) place limits on continued accumulation (Jackson 2019; Moore 2015). Profit demands consumption, and yet the limits of extractivism demand not increased consumption to amp growth, but less to sustain the planet.

Empirically, there are many signs of stagnation and few signs of the resumption of a strong growth trajectory. Despite a general “recovery” from the Great Recession, global growth rates, and especially those of the core capitalist economies, continue a declining trend that began in the 1970s. There are also many signs that the fundamental conditions that led to the crisis of 2008 remain unaddressed; accumulated capital hesitant to invest in production, high levels of indebtedness and inequality. Perhaps most importantly, signs of overaccumulation have increasingly appeared in China, whose growth had maintained global demand through the recession. This all suggests that we might be in for a resumption of crisis conditions and a long period of depression, with its associated social, political, and cultural consequences. However those are understood, it is undeniable that capitalism is a system that depends on growth, as a motive for continued investment and as a basis for its legitimacy as a progressive social order.

The Rise of “Populism” and Authoritarian Nationalism

The emergence of right-wing nativist authoritarian “populism” is the second major inspiration for comparisons to the interwar period. The 1920s and 1930s saw a shift from liberal democracy to authoritarian regimes; many of them characterized by violent racist and nationalist politics. Although contemporary movements have not reached the extremes of the interwar, the 2010s has also seen the erosion of liberal democracy , in many cases accompanied by an intensification of national chauvinism and racism in rhetoric and policy. While organized paramilitaries of Blackshirts and Brownshirts have yet to appear, there has been a documented increase in racist violence in the United States and Europe (Levin and Nakashima 2019).

Much of the literature comparing these two periods looks to the rise of historical fascism, often among other kinds of authoritarian episodes, in order to derive more general lessons for “how democracies die” (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018), and, accordingly, how to shore up liberal democracy in the present. A parallel and more complex discussion of “populism” also often invokes the experiences of the interwar period in order to understand contemporary political phenomena, again generally from the perspective of safeguarding liberal democracy. Both analytical moves depend on a significant degree of homology between contemporary illiberal movements and those of the 1930s, that is that (some of) what is called “populism” today shares similarities with what was called fascism then. There are a variety of views, of course, on what it is they may have in common and to what degree. Certainly, there is enough common ground between the discourse of contemporary nationalist right-wing movements and those of the 1930s to make the comparison tractable, although there is a general agreement that fascism is distinguished by its much greater commitment to the celebration of militarism and violence and more total abnegation of liberal democracy (see, e.g., Finchelstein 2017), as well as variants of “corporatist” ideology. Less often appreciated is that fascism was also much more highly organized than contemporary “populisms,” reflecting its emergence in a densely organized interwar Europe (Riley 2019).

Politics and Economy in the Emergence of Right-Wing Authoritarianism

In much of this analysis, there is an emphasis on identifying how fascism or populism “work,” that is, as distinct kinds of political practices or techniques, which are contrasted with a normative liberal democracy. This technique is usually identified as the cultivation of a polarizing “us-versus-them” discourse, together with a disdain for legitimate opposition and of virtues of “tolerance and forbearance” (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018; Stanley 2018). The global trend toward authoritarian populism is often represented by liberal critics as a metastasizing, autonomous logic, rather than as a product of the liberal capitalist “democracies” from which they tend to emerge.

However, there is usually at least some recognition of broader social processes, which are important for accounting for why authoritarian nationalism has occurred in waves at these two moments. “Economic hardship” is often indicated as one of the conditions of public support for illiberal political movements (Eichengreen 2018; Mounk 2018; Stanley 2018), which provides the most obvious means of explaining the surge in right-wing authoritarianism in the wake of these two moments of global crisis and depression (noting that historical fascism was gestated by a much longer period of crisis—going back to the First World War at least—even if the depression encouraged its further diffusion). At the same time, however, right-wing movements have not generally had their base of support in those most directly affected by these economic dislocations; the translation from economics to politics is culturally and socially mediated, not least by racism, nationalism, and patriarchy. In particular, the “commodity fetishism” that systematically obscures the social relations of production contributes to a racialized interpretation of economic processes, so that financial crises and the scarcity of employment or public services can be attributed to Jews, migrants, African Americans, or others (see, e.g., Hochschild 2018; Postone 1980; Stanley 2018).

Some argue that new communications technologies in both periods (radio and film in the 1930s, Twitter and Facebook in the 2010s) allowed for the rise of political movements that bypassed the established “gatekeepers” of mass communication (Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018; Mounk 2018); the implication of this argument, of course, is that right-wing authoritarianism is only held in check by elites committed to liberalism, hardly a democratic thesis. To this might be added that insofar as technocratic liberalism depends on the prestige accorded to elites, especially those in charge of finance, it is vulnerable to crises that make evident the limits of their own abilities as well as their willingness to submit the state to their own interests.

This raises the question of how the rise of populist politics reflects the contradictions and limits of capitalist liberal democracy, a theme that characterizes writing in Marxian and radical democracy traditions. This critical stance toward liberal democracy and capitalism often means a more nuanced view of its alternatives; all “populisms” are not created equal, and political antagonism may be by turns necessary or inevitable.

An influential interpretation of populism in relation to broader social processes, and even the logic of democracy itself, has been advanced by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. Laclau and Mouffe have argued that populism expresses real antagonisms and that it is the fundamental process whereby political and social change is effected in modern societies. For Laclau (2007), populism articulates the unrealized demands of diverse social actors into a common political identity. Populist movements create the conditions for this articulation by deploying “empty” or “floating” signifiers, including words such as “the people” and the persona of a leader—which the discontented then fill with their unrealized expectations. This popular identity must, furthermore, always be anchored in opposition to some external other—the oligarchy, capitalists, Jews, foreigners, etc. While it can be either progressive or pernicious, this operation is, they claim, the basis for any politically induced social transformation. These same mechanisms that articulate identity around empty signifiers and in opposition to others would then provide a common logic shared by both the interwar fascists and today’s “populists” on the right and the left, many of whom were directly influenced by Laclau’s writings (Anderson 2016).4 At the same time, Laclau and Mouffe have long argued against any essential relationship between the economic and the political (2001 [1985]), which limits the ability of their theory to address the relationship between the emergence of populism and phenomena such as economic depressions.

Mouffe (2009) adds to this framework, however, an important emphasis on the affective content of politics: in particular, that any social order generates antagonisms that need to be channeled. If antagonism is not taken up by the Left and channeled toward progressive aims, it will be channeled by the Right in racist, xenophobic, or patriarchal programs. Here, liberal “forebearance and tolerance” can only be maintained insofar as antagonism is transformed into a less totalizing “agonism,” but conflict cannot be wished away.

This opens the important question of the affective basis of right-wing authoritarianism and responses to it. If contemporary right-wing movements have not (yet) reached the levels of glorification of violence of their interwar predecessors, the mobilization of spectacular forms of symbolic and material violence against targeted groups is a predominant feature of these movements, as is the apparently transgressive pleasure (jouissance) with which they are carried out. This joyful violence against targeted groups sets these movements apart from the staider violence of establishment postwar liberalism, which usually at least pretended to regard violence as a tool to be used with regrets in the interest of a universal humanity. This makes for a qualitative relationship with interwar fascism and its celebration of violence against minorities and dissidents, which is certainly one of the principal reasons for the popular culture of comparison of these movements. It also complicates the explanation of these movements in class terms as reactions to capitalist crisis (as Gramsci found [Adamson 1980]), just as much as it leads to a series of unresolved questions about how to combat these movements, through what combination of affective or programmatic strategies. Sharpe, in his essay for this volume, highlights the potential of internationalist love—which is a distinct starting point from Mouffe’s argument for a left embrace of antagonism (see also West and Ritz 2009). Rather than opposition to a “constitutive outside” providing the grounds for unity, for Sharpe “the ability to envision what is held in common is the psychic corollary of the broad coalition.” Lawler’s chapter complements this argument, exploring the mobile solidarity of the hobo as an alternative to the nation-state commitments that animate much contemporary left-populist thinking.

Dylan Riley (2019) provides an alternative framework more grounded in political economy, which is in turn employed by several of our contributors, including Souvlis and Lalaki. Riley argues that fascism arose in the context of an increasingly organized civil society, which articulated demands, especially working-class demands, that could not be satisfied by the liberal democratic order. Fascism arose therefore in a scenario of class conflict in which ostensibly democratic parliamentary politics was unable to effectively represent democratic demands. That democratic deficit also characterizes the elite-dominated liberal democracies of the neoliberal period and became especially evident as European polities in crisis encountered serious barriers to any kind of democratic politics in the directives from the EU. The major difference between the two moments for Riley is precisely the weakness of popular and civic organization in the contemporary period: the lack of a party base makes Trump more of a “Bonapartist,” seeking the particular interests of his family patrimony, than a fascist. This low level of organization is also, of course, complemented by the absence of any real anti-capitalist popular organization, one of the factors that contributed to the violence of the interwar period and of interwar fascism. If authoritarian right-wing movements again serve capitalist interests, it is now in a context where capitalist rule is much less actively contested.

Gandesha (this volume) argues that the terms of class conflict have also changed, as contemporary modes of accumulation no longer depend to the same degree on the exploitation of labor in production. Political conflict in capitalism, to be sure, now centers much more on ecological questions than it did in the 1930s. Many of the contemporary right-wing authoritarian movements (notably in the United States, the Philippines, and Brazil) have featured a rollback of environmental regulations in the service of extractive industries. Another dominant issue today is the exclusion of migrants from relatively privileged regions of the global capitalist system, which often features more centrally than the class relations in production.

Barriers to migration are often portrayed as the protection of national labor markets and social welfare systems. These initiatives can be understood, in fact, as illusory forms of social protection of workers in the capitalist core, relating contemporary right-wing movements to Polanyi’s diagnosis of fascism as a (suicidal) attempt to re-embed labor, land, and money in society. In this sense, right-wing and populist movements in both moments can be understood as reactions to the chaos brought on by financial expansion, the burdens of debt, increasingly precarious work and the cultivation of anxiety-ridden, risk-managing subjects (Martin 2002), together with the evacuation of a sense of a progressive capitalist future as the system endures its either periodic or secular stagnation.

Finally, there is a clear tendency toward gender and sexual oppression in the right-wing movements of both periods, although they have sometimes also created openings for certain kinds of protagonism by women, as Peto’s chapter demonstrates. The tendency toward a more oppressive gender politics may have more to do with continuities in the politics of the Right than with the historical conjuncture; as Nancy Fraser has argued, the politics of “emancipation” is a third moment that cannot be subsumed in Polanyi’s double movement (2013, chap. 10). At the same time, however, as Tzanaki’s chapter shows, a continuity in the policing of women’s sexuality also opens up opportunities for the use of sexual politics as a tool of control in the context of economic crisis.

Debating the Appeal of Authoritarianism: The Psychological Dynamics of Right-Wing Authoritarianism

The related concepts of the “authoritarian personality” and “right wing authoritarianism” provide another explanation for the emergence, in both periods, of movements that advocate gender and sexual oppression, nativist and racist persecution, and restrictions on civil and political rights. Proponents have used extensive survey research to demonstrate that there is a population of persons with an “authoritarian” psychological profile, which combines a disposition to order, stability, and hierarchy on the one hand (“authoritarian submission” and “conventionalism”), with a particular enthusiasm for punitive measures against “others” that are understood to threaten social stability and cohesion (“authoritarian aggression”), on the other (Adorno et al. 1950). Some influential contemporary interpretations emphasize how these tendencies are “activated” by the perception of threats (rising crime, terrorism, unemployment, pandemics), or even by evidence of social changes in sexual norms, racial and gender hierarchies, or increased diversity (see, e.g., Stenner 2005). Of course, they are also enabled by the politicians that craft the messages that appeal to, encourage and authorize these impulses, both by stimulating fear and by presenting authoritarian solutions to the constructed “threats.”5

This framework provides explanations for the subjectivity of mass support for authoritarian politics, including some aspects that are otherwise difficult to account for: why seemingly unrelated causes (e.g., racism, anti-gay politics) tend to go together in right-wing movements, why the targets of right-wing politics are often fungible (see Briskey, this volume), or why these movements direct so much vicious cruelty toward relatively powerless minorities. Furthermore, the concept of “activation” might explain why we see a resurgence of such authoritarian sensibilities now as in the 30s, insofar as the “systemic chaos,” rapid social changes, and political and economic uncertainties that characterized both periods (albeit in distinct degrees), could serve either as triggers for an authoritarian psychological profile, or as motivating contexts for political leaders to make authoritarian appeals, especially given the difficulty of articulating more progressive hegemonies in moments of capitalist stagnation.

The debate over the psychological origins of the authoritarian profile is beyond the scope of this essay. However, a note of caution is warranted by the emphasis on the putatively enduring psychological dispositions (such as overly strict fathers or susceptibility to disgust), rather than on critical exploration of the social, cultural, and historical production of authoritarian dispositions, and, especially, their affinities and targets (see Gordon 2018). As we know, race, ethnicity, nation, gender, and the state are social and historical constructs, whose relation to affective states must also be historically produced. A framework attentive to the social construction of these categories in the context of capitalist liberal democratic states—as well as to the internal and external contradictions of each category—would help to advance understanding of how psychological dispositions are converted into the recurring form of right-wing authoritarianism. Gandesha’s chapter in this volume (as well as his ongoing work elsewhere) advances toward such an integral conception of authoritarianism.

Identifying the Limits of Liberalism: Capitalist Liberal Democracy’s Internal Contradictions

Capitalist, liberal democracy seems to imply skating a series of contradictions. We are asked to defer to and honor national leaders, who are often regarded as extraordinary if not nearly superhuman in their capacities, and as who we should trust to look out for our collective interests—but only up to a point, after which we slip from normal to authoritarian obedience. We are asked to prioritize a national community, to which we owe our primary allegiance, and should even be willing to sacrifice our lives, but also to accept that we are part of a global division of labor, with free movements of goods and capital, but of people whenever and only insofar as it is authorized by the state. We are told that the people are the authors and agents of democracy, but that this is limited by constitution, convention, technical expertise, and the independence of the central bank. Authoritarianism, populism, and other illiberalisms are therefore implicit in the precarious structure of liberal democracy itself. And this is not to mention the contradictions of capitalism, or between its systemically inflated promises and its realities.

One way of framing these movements is as movements for social protection and constituent power in the context of a crisis of global capitalism. As Riley (2019) argues, historical fascism was a kind of authoritarian democracy, insofar as it promised to channel the popular will (and even sponsored means for mass participation)—it just claimed that liberalism and elections were not the means to do so. Insofar as they were “revolutionary” regimes, they appealed to the people’s constituent power, the democratic right of the people to remake the foundations of its political system, which always lingers as a potential destabilizing contradiction in any constituted order that claims to run democracy according to established rules (Kalyvas 2009). Contemporary populists also appeal to constituent power, even if they are less explicitly revolutionary: they consistently challenge the institutions of liberalism as fetters on a popular will which they uniquely represent. Here, much of the responsibility for current movements rests in the limits of neoliberalism as an antipolitical formation that denied any possibility for collective agency over and against the rule of “market forces” (Brown 2015), as demonstrated in this volume’s chapters by Wilkinson, on authoritarian liberalism, and Gökariksel on “militant democracy.”

The appeal, however indirect, to constituent power helps to explain the temporal structure which Griffin (2008), describing “generic fascism,” has characterized as palingenesis, or “the myth of rebirth”: on the one hand, the evocation of constituent power is an appeal to make a new future, and on the other hand, as racist or nationalist movements, they appeal to a (usually vaguely defined) collective past to ground essentialist identities. This temporal structure is equally evident in Mussolini’s combination of futurism with the valorization of ancient heroism—common in one way or another to most European fascisms—and Trump’s famous slogan, Make America Great Again. If today’s populist right lacks the futurist imagination of their predecessors, then that lack might reflect the generalized inability to conceive of a future beyond capitalism, even despite the less than shining future that capitalism seems to promise now.

Seen as movements that articulate illusory versions of social protection and constituent power in the context of a crisis of global capitalism, the rise of right-wing authoritarianism can be seen less as an external threat to liberal capitalist democracy than as the expression of its unresolved contradictions. Something of the same could be said for the contradictions between the national state and the globalizing and universalizing drive of capitalism and liberalism. The extreme violence of the interwar had everything to do with war, which has itself often been explained as a result of intensified competition between national states for territory, resources, and markets, in a world divided into increasingly closed territorial systems which excluded the newly industrializing, and territorially poor, states such as Germany, Japan, and Italy. Arrighi (2010) in turn attributes this competition between national states to the increasingly zero-sum competition between capitals in existing lines of production and the consequentially increased availability of surplus capital for investment in war-making. While, again, the contemporary period does not demonstrate the same degree of confrontation between capitalist states, there have clearly been movements in this direction, including the “new imperialism” initiated by the younger Bush administration (Harvey 2003), and, more recently, the specter of a “trade war” between the United States and China. And again, this increase in intercapitalist rivalry seems to follow an extended period of overaccumulation and saturation of investment opportunities in existing lines of production; notably, China has ceased to be only an assembly platform for foreign transnationals and has developed its own firms competing in established industries (autos) as well as on the technological frontier (solar energy, 5G, artificial intelligence). What’s more, this more aggressive assertion of “national interests” in commerce has gone hand in hand with a more general assertion of nationalist nativism, including the exclusion and persecution of migrants and the targeting of Muslim minorities as an internal enemy: which confirms the relevance of Arendt’s (1951) argument that fascism represented imperialism “brought home” (an argument developed by Buscema and Taek-Gwang Lee, in this volume).

While it may have seemed at the end of the twentieth century (as at the end of nineteenth) that a liberal, globalizing capitalism was transcending nationalism, it has become increasingly clear that the nation-state remained the seat of popular identification and legitimate political authority, capable of being remobilized. Although it is certainly likely that the force of any return to nationalist imperialism will be blunted by the economic integration and cosmopolitanism promoted (in part) by the globalization of liberal capitalism—as well as by the unimaginable destruction that would be brought by warfare between major capitalist states today—the contradictory foundation of liberalism in the national state means that ugly, racist, and xenophobic illiberalism will continue to plague the liberal capitalist project.

The Organization of the Book

In Part I of this volume, “Crises of Capital and Hegemonic Transitions,” contributors examine one of the most common comparisons drawn between the 1930s and the present in both popular and academic discourse: the financial crises and economic downturns that characterized both eras. These authors ask whether and to what extent these parallels reflect a capitalism in crisis—whether that crisis is figured as financial collapse, secular stagnation, or systemic transition—and how might we hone or enrich those understandings in and through comparison with the 1930s. Drawing on the work of Adorno, Arendt, Arrighi, Benjamin, Césaire, Gramsci, and Polanyi, among others, these chapters push us to rewrite the narrative of economic transition: three middle chapters take the standpoint of national and regional frames outside the North Atlantic—Latin America (Rayner), Greece (Souvlis and Lalaki), Hungary (Pogátsa)—and they are bookended by theoretically expansive arguments (Gandesha, Buscema) about capitalist accumulation and the temporality of transition. Together, these chapters provide a series of perspectives on the organization of capitalism and the juxtaposition of cyclical repetition and secular transformation.

In Part II, “Authoritarianism, Populism, and the Limits of Liberal Democracy,” contributors pick at a different seam in the stitching often used to tie together the 1930s and the present, a thread that winds through both eras to connect liberalism and democracy to the rise of ostensibly illiberal, often explicitly nationalist or nativist, populism, and authoritarianism. These chapters do not assume that liberalism is a natural, ideal, or even historically uniform political order—the telos of political evolution—in comparison with which other forms of politics can only appear as aberrations. Instead, they assume a critical stance to liberalism and its relationship, empirical and ideological, to capitalism and democracy. Indeed, they seek to reveal the authoritarianism inside of liberalism, the ways that the state is mobilized in defense and in support of economic liberalism, while constraining and repressing democratic forces from below. At the same time, these chapters maintain an equally critical focus on the populist, nationalist/nativist, and authoritarian movements that have emerged throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as liberalism’s loudest challengers—asking, for example, how the “people” are imagined in different moments and by different forms of left- and right-populism, and what kinds of solidarities—of race and class, grievance and resentment, power and privilege—they rely upon. A range of regional and national cases—on Western Europe (Wilkinson), Turkey (Burc and Tokatli), Hungary (Taylor), Brazil (Fogel), and Eastern Europe (Gökariksel)—is anchored by a shared orientation to the contradictions within liberal capitalism.

In Part III, “People in Movement: Practices, Subjects and Narratives of Political Mobilization,” contributors focus on the work of protest and political mobilization in the 1930s and today. Drawing on cases from both “right” and “left” movements in both periods, these chapters explore how political subjectivities are formed, and how people are moved to action, whether in revanchist governance or in popular struggle. Together, they reveal how movements are linked together, often transnationally, by their aims (e.g., antisystemic struggles against exclusion and exploitation) and by cultural resources and affective identification. The opening chapter (Jung) mobilizes the news to map a global landscape of protest movements; the four chapters that follow—on radical poets on the global scene (Sharpe) and radical countercultural left writers in the United States (Lawler), Hungarian Far Right women’s movements (Peto) and Italian post- and neofascists (Broder)—dig into the affective, often literary motivations and manifestations of bodies politic-in-formation. The latter two chapters describe how neofascism and authoritarianism can appropriate modes of representation from the Left, even claiming as their own the struggle to defend workers, women, the socially marginalized, and economically downtrodden—those who feel they have lost something. In the process, they adopt a cultural politics (indeed, an “identity” politics) of their own. Meanwhile, the former two chapters also consider the possibilities for the creation of new solidarities in the face of violent and exclusionary authoritarianisms, that might prove capable of interrupting the legitimization of white nationalism and autocracy.

In Part IV, “Body Politics/Political Bodies: Race, Gender, and the Human,” contributors consider discourses and practices that govern the body in relation to political economy. The rise of racist and ethnonationalist biopolitics is among the most prominent features of both periods. (Indeed, as Taek-Gwang Lee argues in his contribution, fascism is “colonial biopolitics.”) Turning to the person, the family, and the nation, our authors ask how parallels between the 1930s and today make visible and/or obscure a longue durée of racial capitalism and state violence, limning the borders of personhood and delimiting the boundaries of citizenship—and in the process, redrawing the lines of social and political conflict. Two chapters address the rise of racism and ethnonationalism using cases from Asia (Taek-Gwang Lee) and Australia (Briskey), while a third chapter examines the regulation of sexuality in Greece (Tzanaki). The last reading reflects on the present by way of history, while also looking to the future by exploring imaginaries of the human provoked by new technologies and regimes of production (Falls). Across these chapters, contributors are attentive to persistent logics of racialized extraction, exploitation, and disenfranchisement, even as they ferret out their novel forms and effects. In this, they remind us that capitalism necessarily rests on non-capitalist foundations, is constituted and sustained through noncapitalist, even nonmarket practices: domestic work, imperialism, feudalism, slavery.

Each chapter in the book has been paired with an image; these images were not necessarily chosen as literal illustrations, but offered as provocations to help us to think about the content of each chapter, to meditate on presentations of history and crisis, to scrutinize counterhegemonic initiatives, and to encourage readers to place each work into conversation with other materials in the collection and elsewhere. Taken together, these chapters take the 1930s and 2010s as mirrors that reflect one another, as lenses through which to inspect one another, and as archives from which to pull object lessons. When we turn, or return, to the 1930s, we do so not simply to confirm emergent common sense, but to reframe, reshape, and re-engage contemporary struggles.