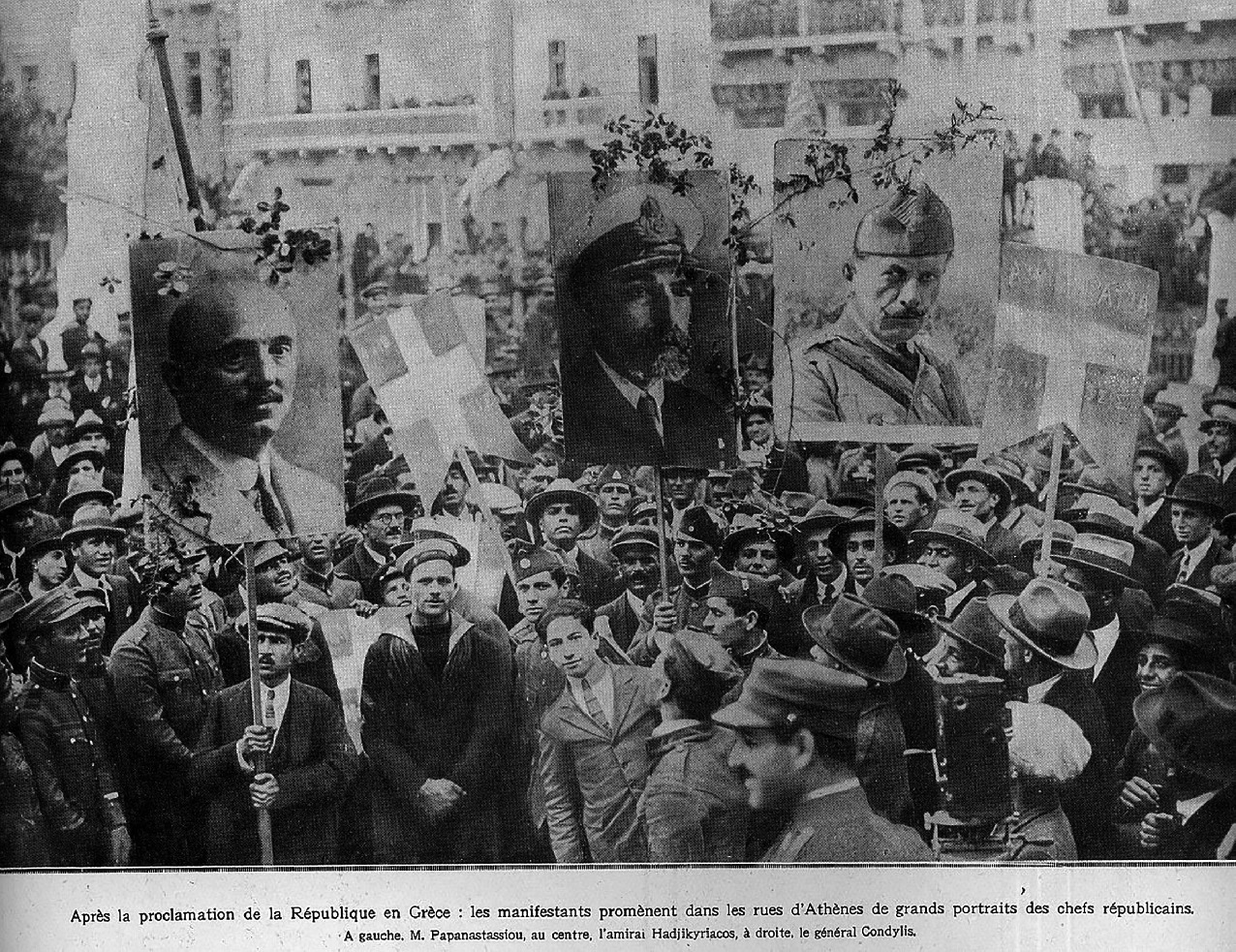

Declaration of the Second Hellenic Republic (1924–1935)

Golden Dawn Trial/Kalariti’s Apology by Molly Crabapple. Image provided by courtesy of the artist

Similarities at the causal level (e.g., economic crises), but not at the empirical level, (i.e., political impacts during both periods), give form to what we call a “contrast explanation.” This approach identifies how a set of similar causal mechanisms produce different events. In trying to understand why x rather than y appeared in circumstances where y was expected, we take as a starting point Dylan Riley’s (2019) explanation of fascist regimes according to which the development of civil society may happen in the absence of a hegemonic politics. Organic crises, as Gramsci describes, are situations in which civil society’s democratic demands cannot be sufficiently addressed through the existing political institutions, may lead to a crisis of representation in which “the traditional parties, in that particular organizational form, with the particular men who constitute, represent, and lead them, are no longer recognized by their class (or fractions of a class) as its expression” (Gramsci 1971, 210). The fascism of interwar Europe, as Riley explains, did not arise out of a pathological form of civil society, but as a form of associational politics expressing a desire to “make the modern state more representative of the nation than was possible with liberal parliamentary institutions” (Riley 2019, 11). Having conflated liberalism with democracy and authoritarianism with antidemocratic movements and regimes, critical literature on civil society has largely missed this point.

A crisis constitutes a turning point in time, but also disruption and discontinuity. In history and historical sociology, a crisis is understood as an “event”—these “relatively rare subclasses of happenings that significantly transform structures. An eventful conception of temporality, therefore, is one that takes into account the transformation of structures by events” (Sewell 1996, 262). Yet an event—often listed as a synonym of crisis—is a mechanism linking past and future, and its importance is primarily established in terms of its location in time and space as well as in relation to a series of other events. There is little one can understand about the current crisis, the meteoric rise of Syriza and its electoral victory, or Golden Dawn’s inroads into parliamentary politics, unless they are placed within a historical perspective and explained as a constellation of factors and contingencies, as a series of social interactions impinging on each other in space and time. Thus, we offer a synopsis and analysis of the hegemonic and counter-hegemonic politics following the collapse of the Greek Junta, during the era known as metapolitefsi, meaning polity and regime change, up until the eruption of the 2008 world crisis. Similarly, we trace the links between the Metaxas dictatorship and the series of events that preceded it.

Intra-Bourgeois Struggles and the Metaxas Dictatorship

The Archimedean point of interwar Greek politics was the Goudi coup of August, 1909. Organized by the officers of the Military League, the coup aimed at putting an end to the previous, “corrupted” political order. Its main outcome, however, was to introduce Eleftherios Venizelos into the political scene; a Cretan liberal politician who would remain the central political figure of Greece until his death in 1936 (Maroniti 2010). Socially, the consequences of this event were decisive for the fate of modern Greece: Scholars of the Greek interwar period define it as a “bourgeois revolution,” since the Venizelist project was backed by, and consciously foregrounded the interests of, the “commercial, shipping and industrial bourgeoisie” (Mavrogordatos 1983, 123). More precisely, as the historical sociologist Kostas Tsoukalas (1976) has argued, the Goudi coup resulted in the dethronement of a specific section of the bourgeoisie, which aligned socially with landowners and found political expression in the old political establishment, the same fraction that endorsed Royalism.

In political terms, the project of bourgeois modernization crystallized in the formation of two broad political coalitions, Venizelism and Royalism. The former based its political identity on the Greek Republic, the latter on the institution of Monarchy. Τhe respective political epicenters of these two coalitions were the Liberal Party, with Eleftherios Venizelos as its leader, and the People’s Party, led by Dimitrios Gounaris and then Panagis Tsaldaris. The precise composition of the coalitions changed according to the conjuncture, in which the two aforementioned parties were joined by smaller parties ideologically affiliated with them (Hering 2008).

These political coalitions gained legitimacy by deploying a traditional patron-client dualism, with the former being constituted either by individuals or by wider groups and institutions. Parliament members in this system were notables who, with the aid of intermediaries entrenched in the constituency of the patron-politician, traded favors for political support from below (Charalampis 1996). This relationship derived from a society in which the peasantry was a central social category. It had a vertical and contingent character. This feature of Greek parliamentary democracy between 1918 and 1936 accounts to a great extent for its later dissolution, as we shall see. More narrowly, we argue that the continuation of the pre-modern clientelistic political system as the key mediator of demands from below, within the conditions of post-1931 financial and social crises, could not offer necessary solutions to a society obtaining an explicit class character and in need of modern universal state institutions that could intervene and regulate the relationship between labor and capital. In other words, the state’s inability to offer class-oriented solutions to a proletarianized populace, while insisting on a traditional laissez-faire mentality at the level of the economy and advancing clientelism as a form of political mediation, transformed the hegemonic crisis that the political system was confronting into an “organic crisis”, ultimately leading to its dissolution and to the establishment of Metaxas regime in August, 1936.

A possible solution to this impasse would have been for the two key political coalitions to establish impersonal local political organizations in their constituencies to create stable relationships with the groups they were aiming to represent, and to put forward and press for state policies that would address their demands. Neither coalition implemented these possible solutions in the 1920s, or even in the 1930s, when the sociopolitical crisis was more than apparent. The responsibility for the persistence of a traditional party structure lay with notable MP’s in each coalition who were afraid that a change in the Liberal and People’s Parties toward a modern mass party structure would reduce their political influence (Mavrogordatos 1983, 86, 114).

The only exception to this reasoning was the Communist Party of Greece that, since its founding, followed the organizational logic of the socialist and communist parties of the period in building local branches and having the working class as its point of reference. The Communist Party’s influence throughout the interwar period would be limited because of its position on the Macedonian Question, and because of its targeting of the urban working classes, which were a minority compared to the rest of the laboring populace (Sfikas 2004, 45; Mavrogordatos 1983, 148). This would change only in the mid-1930s when the party changed its approach to both issues, significantly widening its audience. It was this structural feature, a potential mass party with local branches, together with the conjunctural change of its political direction through the adoption of the popular-front policy, which accounts for the fear that the political establishment developed toward the Communist Party in the mid-1930s. In fact this was a time when the party’s structures had almost collapsed and the possibility for an immediate takeover of political power by the communist forces was rather remote.

Antivenizelism essentially represented a survival or even a resurrection of the class alliance which had characterized the ‘historical bloc’ of 19th century Greece (i.e., Old Greece). Bourgeois landowners, rentiers, and financiers around the National Bank, artisans and other precapitalist petty bourgeois strata, and the yeomanry had been integral parts of this alliance, constituted under the hegemony of the state bourgeoisie and the auspices of monarchy….In contrast Venizelism represented an effort to establish and consolidate the new hegemony of the entrepreneurial bourgeoisie at the head of ‘several classes joined together in some general direction,’ that is, in a “national” party inspired by a comprehensive program. This program originally combined pragmatic irredentism with drastic internal reform and seems to have initially attracted widespread popular support among all petty bourgeois, worker, and peasant strata. (Mavrogordatos 1983, 180–181)

Both hegemonic blocs were under bourgeois rule; they privileged different specific class fractions even as they shared a sacrosanct value: the reproduction of capitalist property relations.

Returning to our narrative of events of the interwar period, the first crucial radical move in Venizelism was the distribution of the big landed estates to peasants without land property with the objective of gaining social legitimacy from below. The urgency of responding to this social demand became clear after the bloody Kileler rising of 1910 when the peasants revolted against land owners (Kontogiorgi 2006, 122). From this point on, a historical bond between the peasants and Venizelism was created. This political decision had long-term consequences for the country, since the peasants and the agrarian movement remained under the hegemonic rule of bourgeois politics, which prevented the kinds of developments that took place in other parts of Europe, such as the creation of systematic agrarian organizations from below and the consequent revolts that elsewhere contributed to the emergence of fascism (see Riley 2019). Venizelos made a conscious decision to bond the party to the peasant population in order to guarantee, on the one hand, its electoral support throughout the interwar period, and on other, to stabilize the bourgeois status quo.

The next event to define the character of Greek interwar politics, and society in general, was the political divide that emerged in 1916–1917 between the supporters of Venizelos and the supporters of King Constantine over the issue of whether or not Greece should participate in World War I. The debate provoked intense political polarization, the “National Schism,” which lasted until the establishment of the Metaxas regime in 1936 (Tassiopoulos 2006, 260). This division reflected two different world-perspectives: Venizelism had an extroverted imperialist vision, aiming to use alliance with the Entente to gain access to new markets that would benefit the Greek and British economic elites who endorsed its hegemonic project, while the Royalists adopted an introverted, defensive political outlook to protect the existing order of things and the social classes that would be affected by the capitalist expansion (Varnava 2012).

The victory of the Entente in World War I allowed for the continuation of the imperialist expansion in Turkey by securing an expansion of the Greek domain in Smyrna, and the political domination of Venizelos with the exile of King Constantine on June 15, 1917 (Clogg 1992, 264). The “victory” of the Greek army on the side of Entente worked as an additional factor preventing a fascist movement from emerging in the post-World War I conjuncture in Greece. But socially, the continuation of the war for over a decade alienated many of Venizelos’s supporters, making for an even more fragile hegemonic project (Mavrogordatos 1983, 143).

Despite the gains of Venizelos’s diplomatic negotiations in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, his party was unexpectedly defeated in the national elections of 1920, leading him to leave the country (Vatikiotis 1998, 110). The Royalists, against their electoral campaign promises, continued the war with Turkey that Venizelos had started in May, 1919. An overestimation of the capabilities of the divided Greek army, along with its abandonment by the other big powers, would lead to its defeat in September 1922. After this experience, the Greek state would not be the same (Pentzopoulos 1962, 46).

The defeat of the Greek army in Turkey in the summer of 1922 led to the expulsion of 1.2 million ethnic Greeks from Turkey, their resettlement in Greece, and the delimiting of Greek and Turkish borders by the Treaty of Lausanne the following year (Chatty 2012, 86). These events had significant implications for the geographical, political, and social structure of Greek society during the following decades. On the one hand, delimiting the Greek state put an end to the country’s imperialist aspirations in Asia Minor. This created conditions for the formation of a robust economic elite within the borders of the Greek state, substantially contributing to the economic development of the country (Mavrogordatos 1983, 181). On the other hand, the resettlement of refugees in Greece was a key precondition for the development of a sizable working class, sections of which aligned politically with the Communist Party (Leontidou 1990, 70). In other words, the end of the war, the new borders, and population exchanges between the two countries fostered new social stratifications: two key classes of political modernity, working class and bourgeoisie, which barely existed up until this point.

The next crucial event of the interwar period was the election of August 19, 1928 when the Venizelist camp won and made Venizelos the leader of a five-party coalition (Gallant 2016, 213). In the new conjuncture, Venizelos was aware of the need to diversify his constituency in order to forge a new hegemonic project. Among the subaltern classes, he directed his energy to the peasants of the country. The urban workers could not be integrated in the Venizelist hegemonic block through access to private property as had been achieved with the peasants through the distribution of land. The Liberal Party considered the urban workers a potential danger, and they were left without any provisions. But the peasants, with the state’s help, received access to loans through the Agricultural Bank. In this conjuncture, the upper classes could not expect an expansion of the Greek state and a concomitant opening of new markets through imperialist interventions. But Venizelism did secure loans from foreign banks that were destined, among other things, for public investments (Stefanidis 2006).

The measures provided to the lower classes did not guarantee economic stability, either for peasants who mainly had access to small plots and accumulated debts, or to the urban working class who were low-paid and for whom there were no welfare provisions. In the absence of measures capable of securing consent, Venizelos’s new hegemonic project was unavoidably combined with extensive repression of unrest from below. Indicative of the Venizelist strategy, was the Idionymon, the anticommunist bill submitted to the parliament on behalf of the Liberal Party a few months after the 1928 elections (Ghikas 2004, 68). This was an institutional tool that Venizelos considered necessary to prevent further radicalization of the labor and agrarian social and political forces, especially in light of the radical change of social stratification brought by the advent of 1.2 million refugees. With the passage of this bill into law, anticommunism became an official, integral aspect of the Greek political establishment, filling an ideological gap created by the collapse of the Venizelist imperialist project. Moreover, the unwillingness of Venizelos to adopt consensual measures to integrate the working masses peacefully within the dominant political order was further clarified.

Reactions from below consequently emerged. More precisely, the emergence of the global financial crisis of 1929 ignited the social rage of farmers, many of whom were refugees, whose products were oriented to export markets that were significantly reduced with the collapse of the free market economy (Seferiades 1999, 315–316). Economic hardship, along with the 1930 Ankara Treaty between Greece and Turkey (which stipulated that refugees’ assets in both countries would be considered assets of the departed country) proved crucial for shifting a critical number of the refugees’ votes from the Liberal Party to the parties of the Left. This change was crystallized in elections on September 25, 1932: almost twenty percent of the votes of refugees moved from Venizelos’ Party to the Agrarian and the Communist parties. In the following elections in March, 1933, Tsaldaris’ Party was the largest party within the Greek parliament, conquering 118 out of 248 seats, thus securing victory over the Venizelists after years of successive electoral defeats (Kritikos 2013, 365–366).

The wider context of this shift was the destabilization of the Greek economy—and consequently the Greek political scene—as an effect of the global financial crisis. The devaluation of the British pound on September 21, 1931 had significant economic consequences for Greece that eventually led to Greece’s exit from the gold standard. The increase in interest rates, a significant compression of the real economy, and the decrease of reserves from foreign investors, were some of those consequences. Obligatory protectionist measures adopted by the following governments boosted both industrial development and agriculture. In terms of social impact, these measures slightly improved peasants’ living standards by raising the prices of their products, though it had the opposite effects for the rest of the working people: the urban working class, civil servants, and artisans (Mazower 1991). A worsening of subaltern classes’ living conditions did not come as a direct outcome of the global financial crisis, but rather as a consequence of the Greek political establishment’s failure to adopt welfare provisions. Interventionism to boost the economy was not enough in a historical period during which the crucial issue was the regulation of the relation between capital and labor.

On the surface, this period was characterized by (1) the removal of the Venizelists from the centers of political and military power, (2) the displacement of the moderates by the extremists as leaders of the anti-Venizelist bloc, (3) the further intensification of the National Schism, (4) the restoration of the Monarchy, (5) the growing appeal of authoritarian ideologies among right-wing forces, (6) increased social tension resulting from the social inequalities engendered by Greece’s economic recovery, and (7) continuing state repression of social and labour protest. On a more fundamental level, this period of crisis can be seen as a process in which the intensification of the intra-bourgeois struggle for dominance within the hegemonic bloc (encompassing both Venizelists and anti-Venizelists) developed into a crisis of the traditional political structures and instruments of bourgeois hegemony itself. (Zink 2000, 230)

More precisely, in this new conjuncture, where the Royalists dominated the political game, the role of the King was upgraded to decisively intervening in the world of politics. On March 5, Metaxas was appointed by King George II as Minister of Defense and then Vice-President of the government. This decision revealed the King’s political orientation toward the far-right royalist fractions, since Metaxas had made his antiparliamentarian reasoning public since the end of 1933 (Clogg 1987, 12).

Metaxas became one of the two key figures of the Greek political scene, alongside the monarchy. Considering that neither of them was convinced that political liberalism was the best method of governing in this period of intense social conflict, they decided to abolish the parliamentary regime on August, 4, 1936. The Communist Party of Greece, with its new strategy of popular frontism, and a political system that was in crisis and unable to deal with the intensification of labor strikes and demands, posed a real challenge to the Metaxas regime: its reply was repression, since concessions were out of question. The Metaxas regime followed the political paradigm of the other authoritarian experiments of the period, most notably of fascist Italy and Corporatist Portugal. One of his first political initiatives was to abolish the parliamentary mode of governance, establishing himself in the head of the state along with a council of ministers. Parliamentarism was blamed for the succession or national disasters since the founding of the Modern Greek state, while communism was also considered a threat to national unity. In order to make up for the lack of popular support that a mass party would have provided him with—the National Organization of Youth (EON) was the only mass organization of the regime—Metaxas followed a social policy with some substantial concessions in favor of workers and public servants. Following the example of Fascist Italy, he also established institutions such as the National Labor Service and the Social Insurance Institute. Though his power rested almost entirely upon the army and the monarchy, Metaxas posed as antiestablishment, staffing his ministries with representatives of various corporate interest groups rather than the traditional political elites. Metaxas’ efforts at large should be approached as another fascist attempt of the European interwar period, which did not cancel the march of the country to the path of modernity but rather established an authoritarian version of it.

In sum, the triggers for the establishment of the Metaxas dictatorship are located in the post-1931 conjuncture, in which the political system proved unable to articulate effective hegemonic politics within conditions of political and economic instability. The ongoing crisis made political protagonists turn to authoritarian solutions to overcome a political impasse that resulted from the long-term failures of traditional politics.

Greece in the 2010s: Hegemonic Instability, Emergent Fascism, and the Rise of the Left

Post-civil war (1946–1949) Greece scarcely constituted a model democracy. The term itself, a rather empty signifier at the time, became a rallying cry against communism and the Left more broadly. The fall of the Junta in 1974, however, marked the beginning of a new era. That same year a referendum abolished the monarchy—a source of friction and political contestation since its establishment—and a new constitution declared Greece a presidential parliamentary democracy, ushering in the longest period of political stability in its history. In less than a decade, Greece would become the tenth member of the European Community and, in twenty years, a member of the European Economic and Monetary Union as well.

In the 1980s, while other European states entered the neoliberal era, Greece, under the leadership of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), would get a strong taste of social democracy with the expansion of the welfare state, the creation of a national health system, an expansion of the public educational system, large salary and pension increases, and so forth. Before mutating into yet another European neoliberal party, PASOK largely encapsulated the hopes, but also the fears and reservations, of this small country joining the EU and globalization at large.

PASOK’s early, strong anti-American and anticapitalist rhetoric would quickly fade away. By 1985, PASOK would fully adopt what has been designated as capitalist restructuring (Sakellaropoulos 2018, 203–228): austerity, privatizations, flexible labor relations, credit-based private consumption. On the social level, an oscillation between Europeanist attitudes, identified as outward-looking and modernization-oriented, and anti-Europeanism, namely reluctance toward political and economic union with Europe, understood as introversion, was largely painted as a dichotomy between forward-looking and socially dynamic groups, most often identified with intellectuals, diaspora business, and export capital, and a culture identified with the “underdog” rural and lower middle classes (Mouzelis 1995, 20–21). Yet, if that was the case during the nineteen-eighties, by the end of the century, identification with the European project—at least by the bourgeoisie and the new petit-bourgeois class—was almost complete.

The divide between an “introverted” underdog culture and a modernist culture oriented toward the Eurozone would be explicitly employed by both PASOK and New Democracy, the self-fashioned center-left and center-right, respectively, that dominated the Greek political scene during the metapolitefsi, in order to legitimize technocracy, depoliticization, economic liberalization, and liberal individualism. Europeanism was elevated into a unifying national dogma and a hegemonic ideology designed to achieve an effective political alliance across classes. During the subsequent economic crisis, this same ideological device would be employed again to delegitimize any expressions of social and political discontent as “populist” and even unpatriotic.

In fact, a breach in the centrist neoliberal consensus across the sociopolitical landscape would soon take place. The neoliberal turn that was almost completed in preparation for the country’s membership in the Eurozone in 2002 had led to great social deficits and to a series of large-scale mobilizations, including two general strikes in the spring of 2001 against the government’s plans to reform the pension system. The establishment had serious reasons to fear mass politics and collective action (Papadatos-Anagnostopoulos 2018; Vradis and Dalakoglou 2011).

At this point, it was no accident that civil society took center stage as a pacifying mechanism in hegemonic Europeanist discourse. In a speech to the Greek parliament on the 2001 budget, Costas Simitis—the leader of the PASOK “modernizers” and Prime Minister for two consecutive terms between 1996 and 2004—echoed Margaret Thatcher’s famous statement that “there is no such thing as society,” by suggesting that politics is not shaped by collective social subjects but rather by the individual citizens who compose civil society (Spourdalakis and Tassis 2009, 503). Conceived in Tocqueville’s terms as a specific type of intermediate structure of voluntary organizations and associations located between primary relations, like the family and the state, civil society was primarily viewed as a mechanism that could insulate the state from mass politics, to “discourage thoughts of revolution” (de Tocqueville 1988, 523).

Revolution was in the air, however, as the 2008 insurrection following the murder of Alexis Grigoropoulos suggested. A precursor of the Aganaktismenoi movement and the mass mobilizations that followed, the protests, riots, and university occupations that spread across the country, targeted much more than the police who had been held responsible for Grigoropoulos’s death. A statement in the Greek anarchist magazine Flesh Machine evaluated the situation as follows: “This revolt was, in fact, a rebellion against property and alienation. A revolt of the gift against the sovereignty of money. An insurrection of anarchy, of use value against the democracy of exchange value. A spontaneous rising of collective freedom against the rationality of individual discipline” (Holloway 2015). The uprising was led by anarchist and leftist groups, but it drew people from all walks of life into the streets. A widespread feeling of frustration stemming from rising unemployment, state securitization and repression, and the prospect of an altogether bleak future, especially among the younger generations, was pervasive. The balance between neoliberalism and democracy was further tilted during the subsequent memorandum era when the state took up a new hegemonic role: it devalued the cost of labor and tightened control over it, redistributed wealth in the interests of big capital, and increasingly developed into a police state where protests were effectively suppressed before they could evolve into insurrections and revolts like the one that shook the country in 2008.

The Economic Adjustment Program for Greece, the first in a series of three bailout packages or “memoranda of understanding,” as they are also known, was signed in May 2010, inaugurating a two-year period of insurrectional politics and social unrest including mass protests, organized civil disobedience actions, public sit-ins, and nationwide strikes. In the process—from residents months-long clash with the police in the spring of 2011 over the government’s decision to build a landfill in a small town south of Keratea, to the establishment of Athens’ central Syntagma Square as emblematic of the Indignados-inspired Αγανακτισμένοι movement during the summer of the same year, to the publishing of bootleg news proclaiming that “the revolution will not be televised” during the summer of 2013 in defiance of the shutdown of the state broadcaster, ERT—the resistance movement was reshaping old political identities and giving rise to new ones. While unions, the extra-parliamentary and, to some extent, the parliamentary Left and anarchist groups had important roles to play, this movement—like other movements around the world in the past decade or so—defied conventional understandings of political organization and collective action.

The uprising of 2008 constituted a turning point for Syriza, the Coalition of the Radical Left; it was catapulted from 4.6% of the vote in the 2009 legislative election to just under 27% in the second general elections of May 2012, and then to control of the government with 36.3% of the vote in January 2015. Breaking with the Eurocommunist tradition of Synaspismos, the largest party of the coalition and its “Modernizing Wing,” Syriza largely stood with revolutionary youth in condemning police brutality and the neoliberal agenda of the government. The bulk of far-left organizations in the midst the coalition appeared to undergo a certain radicalization with anti-Europeanist and socialist voices being more clearly heard. The generation of Syriza, formed through the alter-globalization movement and the mass demonstrations in Genova, but also at the World and European Social Forums, supported the “Squares Movement,” despite not taking a leading role. The popular assemblies and self-organized initiatives remained at the core of the movement’s organization, whose members experimented with direct democracy, promoted collective efficacy, and engaged people of diverse political backgrounds and experiences (Papadatos-Anagnostopoulos 2018).

Striking a delicate balance between street and parliamentary politics, Syriza rode the wave of popular discontent (Sheehan 2016). Its polling numbers soared as soon as Syriza articulated an “anti-austerity government of the Left” narrative while reaching out to all the left parties and the dissident elements of PASOK (Kouvelakis 2015). Following the 2012 elections, however, the coalition adopted a centralized form of organization and assumed the traditional structures of old political parties while abandoning democratic processes internally. Built into a “parti d’adherents rather than a parti de militants” (Kouvelakis 2015), Syriza, upon its rise in the government, did not develop organizational links with networks or associations of social agents who could integrally shape and support the government’s actions. The party was reduced to “a speech making device that supports the government” and “people’s mobilization [was transformed] from a generator of real popular power and leverage against the elites’ hostility into traditional forms of demonstration” (Karitzis 2017), changes upon which the government would rely to push its program forward.

The political crisis and the hegemonic instability of the old bourgeois regime created a favorable conjuncture of political circumstances for the rise of the Left but also for the emergence of fascism. Closely associated with the crisis of party representation, as Poulantzas (1979) explains, fascism arises in correspondence to a radicalization of bourgeois parties, in which an effort to continue or restore political leadership results in hardening their grip on the state and movement in the direction of the exceptional state. The almost meteoric rise of Golden Dawn, the neo-Nazi party which received 440,000 votes in the parliamentary elections of 2012—up from only 23,000 votes four years earlier—should be understood in this context. A climate of xenophobia built in response to a surge of immigration, nationalism, and securitization that was systematically cultivated by the government and the media gave rise to extreme-right tendencies which Golden Dawn managed to consolidate.

Not a pariah party, Golden Dawn had, at the early stages of its existence, become acquainted with the structures of the deep state and cultivated close relations with the police and the military as well as the judiciary and other elements of the Greek state (Psarras 2010). In addition to occupying positions within the state, the group engaged in grassroots politics and organization. They established, for example, a “Youth Front” in the 1990s (an echo of Metaxas’ National Youth organization [EON]) and Antepithessi (Counterattack), a magazine directed at a wider youth audience. Later, in the midst of the economic crisis and within a framework of militant direct action, Golden Dawn would attempt to create strongholds in various neighborhoods in the center of Athens, for example, Agios Panteleimonas, and to establish “people’s committees” that would directly take up the issue of “immigrant criminality”. Pogroms and violent attacks, mostly targeting foreigners, became a staple of Golden Dawn’s “direct action.”

Food and clothes distribution events, and a blood donation campaign for Greeks only, were highly publicized by the media and instrumentally employed to show that the party was actively working to fill the social void created by previous governments. Posing as anti-establishment, Golden Dawn would eventually escalate its violent tactics to take on what they considered to be the ultimate enemies of the nation: communism and antifascism. After murdering Shehzad Luqman, a young Pakistani immigrant, in January of 2013, the following September fifty black-shirted Golden Dawn thugs armed with crowbars and bats lashed out at Communist Party members, seriously injuring nine of them. Later that month, the antifascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas was ambushed and stabbed to death.

Conclusion

In his comparative analysis of interwar Italy, Spain, and Romania, Dylan Riley (2019) argues that associational politics—most often understood as a sign of robust democracy—facilitated the emergence of fascism in the absence of strong political organizations and hegemonic politics. Similarly, the Metaxas authoritarian regime, while largely relying on the traditional institutions of family, church, and monarchy, attempted to build mass organizations in place of representative politics in an effort to connect the nation with the state. At the same time, anticommunism was offered as a unifying ideological narrative at a time when the trade union movement, alongside a growing Communist party threatened the establishment with another counter-hegemonic project. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, eight decades later, new political actors strive to establish themselves and offer a counter-hegemonic project to the conjunctural crisis of hegemony that has emerged following two global financial crises.

The collapse of the parliament and the rise of Ioannis Metaxas in the interwar period resulted from the inability of the two bourgeois parties to develop a hegemonic policy that would effectively integrate the other classes. In the memoranda era, the imminent collapse of the political system led to the emergence of Syriza as a central political player in the country’s affairs. At the heart of these two different political events is the different political background of the actors contesting the status quo of the two periods, which should be interpreted both in terms of the development of civil society and its effects on political elites. Metaxas was the elites’ option to manage the political crisis. Prior to abolishing the parliament, he was appointed Prime Minister by the ruling parties, having also the backing of the king. Since he did not have the support of a mass movement, Metaxas attempted to manufacture popular support with the help of authoritarian institutions of mass participation. The emergence of a new competitive, albeit limited, communist movement that challenged the hegemony of the bourgeois political system called for counter mass politics. On the other side, Syriza emerged in the context of a two-year period, between 2010 and 2012, of mass mobilizations which gave rise to movements such as that of the Indignants, Αγανακτισμένοι, which crystalized at the central political level and led to the electoral advances of Syriza.

It is the case that we might be on the verge of new forms of political consciousness, the result of a new revival of civil society, in Greece and beyond. Less optimistic views merely detect a “general political impotence” in the European resistance movement which “looks more like a delaying tactic than the bearer of a genuine political alternative” (Badiou 2013, 44). It is unclear whether these emergent forms of political consciousness will be able to take more concrete shape and structure or provide genuine political alternatives. The meteoric rise, and equally swift fall, of parties like Podemos and Syriza may serve as an alarm about the possibilities of yet another civil society revival, with authoritarian characteristics this time.