Construction works for the new complex to replace the Atatürk Cultural Center (AKM, Atatürk Kültür Merkezi), located right on İstanbul’s Taksim Square, began on February 10, 2019 with a ceremony opened by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan himself. During his opening speech, he described protesters against the new building as “ideologically driven” and not different from those “who reject the country’s war on terror” (TRT Haber 2019). He was specifically referring to the thousands of academics who signed a 2016 petition calling for an end to siege politics in the country’s Kurdish-majority southeast after the June 2015 elections and countless public figures, activists, and journalists, who criticized government measures taken under the state of emergency declared after the controlled 2016 coup d’état.

As part of AKP’s (Party for Justice and Development) so-called Urban Renewal Project for İstanbul, in which many historic buildings and traditional neighborhoods were replaced by high-end housings and/or shopping malls, the demolition of the AKM carried significant symbolic value. The construction of the building was initiated in 1946 but not completed until 1969. It was not only considered an architectural icon of the young and modern Turkish republic, but also indexed Western aspirations of the Kemalist elites, who were devoted to the founding principles of the republic. It was during the Gezi resistance in summer 2013 that the AKM again attracted attention, although it had been out of operation since 2008. Protesters reclaimed the building as a symbol of early republican paradigms such as secular Kemalism and struggled for its preservation by resisting AKP’s neoliberal policies combined with Islamist conservativism since its election to government in 2002 (Karaman 2013; Lelandais 2014). The case of İstanbul’s AKM exemplifies how the AKP government has consolidated power by destroying, rebuilding, and pacifying the remnants of the old order, as well as responding to counter-hegemonic alternatives.

This chapter departs from the aftermath of the June 2015 elections and the controlled coup attempt in 2016, to shed light on measures taken by the AKP government to deepen authoritarianism by transforming state institutions via constitutional amendments that aim at significantly remodeling the constitutional fabric of the country. We argue that these two critical junctures have empowered the Erdoğan government to put Turkey on the course of consolidated autocracy1; it recalls the Schmittian definition of dictatorship as the best form of democracy, where for him the dictator—elected by acclamation—can most accurately portray the presumed (single) will of the people. Both parliament and public debates would only undermine the supposedly united will of the people. Therefore, he concludes that the rule of the people can best be practiced in a dictatorship (Schmitt 2010, 42).

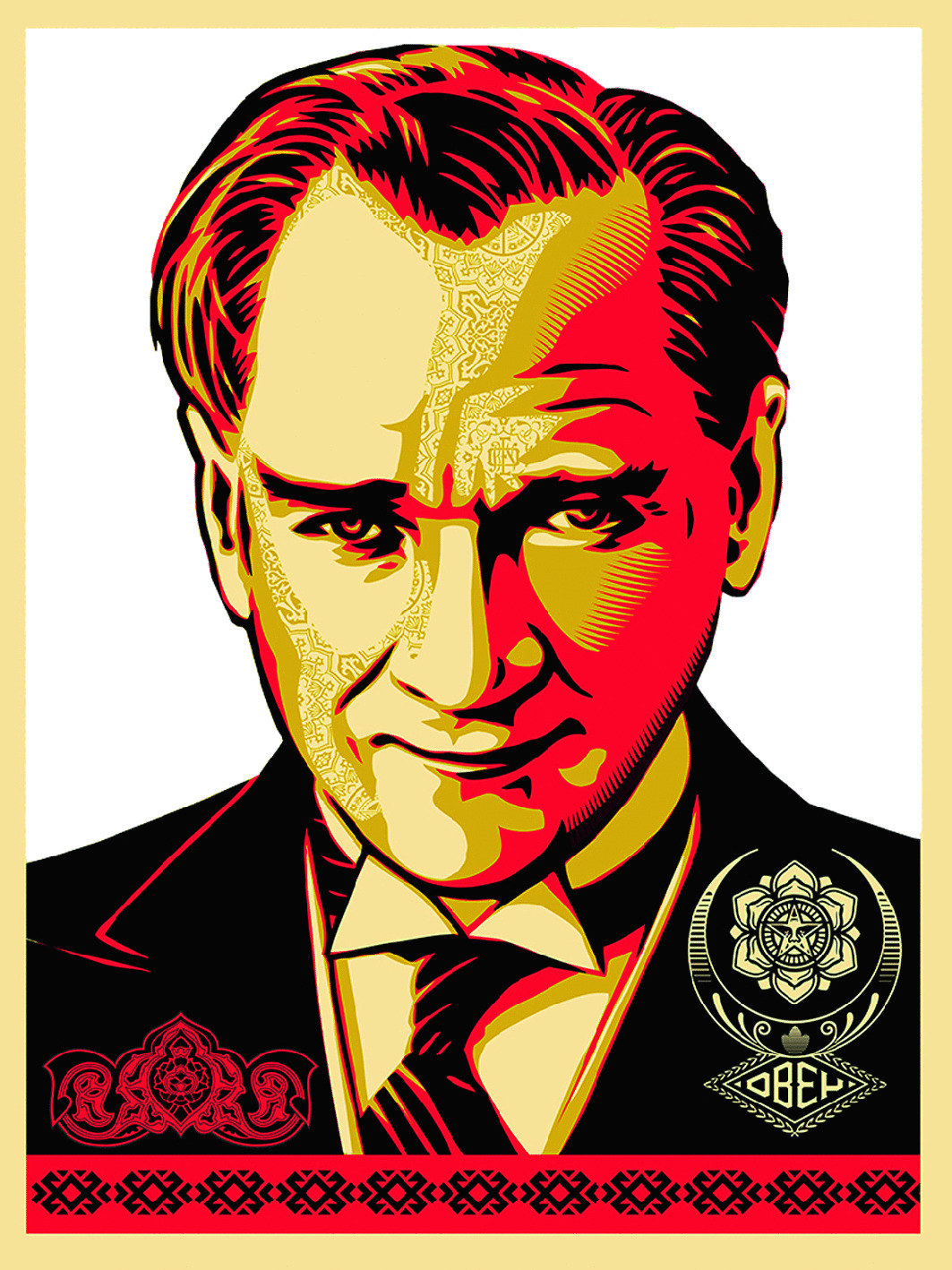

Kemal Print by Shephard Fairey (2008). Image provided by courtesy of the artist

Old-New Turkey?

A first “New Turkey” was announced with the foundation of the Turkish republic on October 30, 1923. It took almost a century until another “New Turkey” was proclaimed in 2018. Building upon the rhetoric of making the state anew nearly 100 years after Turkey’s establishment—epitomized in the “Vision 2023”—campaign launched by the then Prime Minister Erdoğan (Hussein 2018), the presidential and parliamentary elections in June 2018 put a modified constitution in power. This constitution had been adopted in spring 2017 by a narrow margin in an unfree and unfair referendum held under looming suspicion of election fraud (Esen and Gümüşçü 2017; Klimek et al. 2017) and whose foundation was laid in a two-year state of emergency (between 2016 and 2018). The declared state of emergency, advanced as necessary to embodying the Turkish nation in a “strong state” to protect it from internal and external enemies, helped the ruling government to persuade the right-wing radical MHP (Nationalist Action Party), previously opposed the proposal for a “presidential system,” to become a permanent ally in transforming the political system (Burç and Tokatlı 2019).

This “work of persuasion” was largely successful due to the resurrection of a kurdophobe political practice, a cornerstone of the ideological orientation of the MHP, with roots in the early 1930s republican period and in steps taken by the sovereign in a state of emergency. The sovereign here, in a Schmittian sense, is the president, empowered to issue decrees that bypass parliament and that cannot be judicially challenged; in short: the elimination of the separation of powers. Under the premise of restoring order, the last remaining liberal elements in Turkey’s already defective democracy were completely destroyed. Any attempt to evade this repression was framed as rebellion and answered violently, as the case of the imposed siege politics in the Kurdish-majority southeast, as well as severe political oppression against the HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party) will illustrate. As Carl Schmitt put it: “unlimited power was exercised under the pretext of restoring order, and what, in the past, had been called ‘freedom’ was now called ‘uproar’ and ‘disorder’” (2014, 88).

According to the ruling party AKP, the so-called presidential system indicates the beginning of a “New Turkey.” It is the second time that a transformation of the institutional order has been described as the establishment of a “New Turkey.” Especially in the context of the interwar period, the “new” was an integral part in the palingenetic rhetoric of nationalisms underpinning fascist states of the time. As Roger Griffin argues the “new” order was not new per se, since it was based on a reactionary and conservative force, but rather narrated as a revolutionary change that constituted an element of the core myth defined as the “fascist minimum” (1994, 13). In his “great speech” to parliament 1927, Mustafa Kemal spoke frequently of establishing a “New Turkey;” with this terminology he expressed a radical turning away from the old order identified with the Ottoman Empire.

While it remains open for debate as to whether or not Turkey constituted or became a fascist state during this interwar period, we assert that the newly founded nation-state under Mustafa Kemal legitimized the deepening of authoritarianism through the narration of a revolutionary new order, which after the demise of the Ottoman Empire would reposition Turkey in the geopolitical arena and protect it against the colonial interests of Western powers. The rise of authoritarianism in Turkey during the interwar period therefore, as well as elsewhere in Europe, was associated with a transition to modernity, hence with the creation of a “new order” embodied in the violent making of the modern nation-state system.

The “new” under the AKP, however, claimed to break with the “old” order under Kemalism, which ultimately meant a change in hegemony within the state. In both cases we see that the “new order,” be it the republican claim under Mustafa Kemal or the change of constitution under Erdoğan, did not mean the establishment of a democratic order, but rather the deepening of authoritarianism. In both cases, mechanisms of autocratic governance were simply transferred into the new order. The narrative of a “New Turkey” thus served to consolidate power and give further legitimacy to rulers.

Two Foundations and Their Constitutions

From the perspective of comparative politics, we analyze the similarities and differences between the current so-called second foundation and the first proclamation in 1923 based on continuities and ruptures within the respective constitutions. One peculiarity, however, is that the first non-Ottoman, but Kemalist constitution of 1921 exemplified a provisional solution for the following three years and was already modified by a simple majority in 1923 and replaced by a completely new constitution just one year later. Thus, elements of both constitutions (1921 and 1924) will be taken into account.

Constitutions must always be read within their context of creation and we must consider that they index both negative and positive aspects of their predecessors. One aspect both have in common, however, is a claim of breaking with the old order symbolically and factually. In the very first constitution this was explicitly expressed to the extent that, in contrast to the Sultan as the absolutist ruler, the government was relocated to parliament as a whole. Initially, an explicit executive was deliberately dispensed with; instead, all powers were concentrated in the legislature. The absolutist monarchy was in antagonism with popular sovereignty, which was to be carried solely by parliament. Despite a constitutional amendment of 1923, which introduced an elected president and also a prime minister, this pro-parliament spirit was transferred to the new constitution of 1924 and gave the president de jure hardly any powers. At least in the constitutional text, a clear break with the old institutional order can be observed; the genuinely “new” can thus be seen in the locating of sovereignty.

However, there is a significant discrepancy between constitutional writing and its practice. Admittedly, other rules of the game were applied in Turkey where its foundation was tightly led by the president and the presumably strong parliament became just a place where President Mustafa Kemal announced his orders (Solmaz 2016). Thus, the first years were oddly determined by a president who, according to the constitution, did not even exist as an independent organ and after installation in 1923 was quite weak. The subsequent constitution retained the newly created presidential office, and although the constitutional process was strongly influenced by Mustafa Kemal and his supporters, the parliament had to accept the prepared draft beforehand. Instead of mechanically approving the proposal, the deputies deliberated and rigorously restricted the president politically, resulting in another extremely weak president. An example of the parliament’s high degree of self-confidence was when during negotiations in parliament, deputy Reşat Bey said that he would not even grant the president the power to dissolve parliament if Allah were the president, arguing that the parliament is the highest and only organ, which was elected by the people as sovereign (Gözübüyük and Sezgin 1957, 188).

Ultimately, the constitution was adopted with a weak president and many changes were enforced by parliament in this regard. Nevertheless, this reality blatantly diverged from the constitution, with two extremely strong presidents, Mustafa Kemal, and after Kemal’s death in 1938, İsmet İnönü. Basically, both temporal phases of the “foundation” go hand in hand with a strict centralization of state power into the hands of one person and a violent homogenization of society.

It can be argued that aspirations of homogenizing society into a single cultural-ethnic stream as part of a transition to modernity and nation-building of a nation during the interwar period succeeded the Armenian genocide of 1915 that can be seen as its first expression.

With the demise of the Ottoman Empire, however, comparable practices were utilized not “only” to build a nation but to further consolidate the newly established state with nationalist force. Alongside violent actions against the country’s Kurdish population, discussed below, minorities such as Jews during the 1930s and Greeks during the 1950s were subjected to oppressive top-down homogenization policies and nationalism.2

Although this was not initially evident in the constitutional text of the 1920s, political actions and the fundamental antidemocratic conditions of political life such as bans against religious and traditional attire in public and a ban against the passive and active use of the Kurdish language stand against the incorporation of party principles into the constitution, hence a merger of party and state.3 For example, even though women’s suffrage was introduced, elites continued to maintain the electoral system from the Ottoman Empire, which provided rather undemocratic indirect election of deputies (Olgun 2011). Hence, ultimately the party chair decided who was allowed to represent the interests in the capital of Ankara. Again, there was no democratic state in mind, but rather a merger between state and party. This was completed with a ban on oppositional parties and a de facto one-party regime emerged shortly after the establishment of the new state, which contradicted the universalist claims of the Western Kemalist elites. Eventually, a sort of post-Ottoman particularism was established in the guise of universalism (Tokatlı 2019a).

Having the recent controversial Turkish debates on decentralization in mind, it sounds astonishing, but in 1921 a large part of the constitutional text dealt with the provisions of a decentralized order (Tanör 2015, 263) and thus stands in stark contrast to its successors, all of which established a massive centralization of power. While this may initially have been due to the turmoil of the “Turkish war of independence,” it certainly helped the mobilization of local militias on the periphery, as they supposedly would not have to fear a loss of power to the central state once the war was considered won.

Initially, the AKP pursued a similar strategy in 2012, when it forged concrete plans for an obvious change in the government system for the first time, trying to convince enough MPs from HDP’s Kurdish predecessor BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) to adopt their envisaged constitutional amendments. After all, establishing local powers in the provinces, municipalities, and cities would achieve what stands as the essential demand of Kurdish parties throughout the history of the Turkish Republic: decentralization. This is why the AKP decided to “buy” approval for their version of a “presidential system” with such concessions. Accordingly, prominent party members tried to counter the Turkish primal fear of separation through decentralized tendencies.

However, neither during the interwar period in 1924 nor today has power been divided vertically in the state apparatus; instead, there has been a successively more and more rigid centralization. In both cases, military operations against the periphery followed, especially in Kurdish populated areas, to violently enforce national homogenization (Aslan 2007; Küçük 2019; Üngör 2008). This in turn made the initial “efforts” to balance or reconcile peaceful coexistence seem obsolete.

On the contrary, it would appear that both state elites acted according to strategic criteria and were insincere. Additionally, there are apparent similarities in the contexts in which they were created and developed. A common basis was the emergence of a war that ultimately suggested a necessity for something “new.” While the first foundation marked a “war of independence” out of the demise of the Ottoman Empire designed to prevent the premeditated downsizing of the territory to a “rump state” by international powers, the AKP’s war was directed against alleged domestic enemies of the state. Perhaps, at least at the beginning of the twentieth century, one may acknowledge a contextual self-perceived progressive idea, but it is impossible to assert this claim for the war staged under post-2015 AKP rule. Conservative elements were purposively re-enforced to preserve the existing state, rather than in creating a new political order.

Following this thought, the primary motives for action of both actors differ. While the Kemalists always rhetorically emphasized national sovereignty and claimed for it a prominent role in constitutional processes, the AKP’s leitmotif was the establishment of a strong state capable of action. Evidently, this can be seen in the constitutional provisions of the government system, i.e., the relationship between legislative and executive branches. There are further grave discontinuities here. For the first time, the modified constitution of 2018 weakens significantly the legislature qua scriptura, while the executive branch takes on an unbridled role and clearly dominates the rest. It would take significant imaginative power to certify a separation of powers in this scenario.

Rather, this order corresponds to the antiliberal conception of Carl Schmitt’s centralist, authoritative state based on the decisions of a virtuous leader. The recent introduction of constitutionally unusual constructions such as presidential decree rights, which will come into force immediately, actually establishes unchecked rule by a single person. In this way, both Schmitt and the AKP believe that necessary decisions should not be watered down by the often-cumbersome parliamentary processes based on compromises, and that the population—understood as a homogenous mass—can be better represented and governed by a strong executive.

Of course, a prerequisite for this is the destruction of plural elements, which in turn is a conceivable interpretation of the constitutional amendments. Destruction is frequently accompanied by antiliberalism and antiparliamentarianism. For an example of the latter, the legislature is completely deprived of its systemically relevant functions. Not only has its eponymous role been snatched and the president granted the right to legislate bypassing parliament, but the loss of budgetary sovereignty also shows how little power the parliament has left. Parliament can no longer adopt a budget; this is in the hands of the president. The parliament can only approve or reject his proposal. If there is no agreement twice, the previous year’s budget is automatically enacted and the president loses not an iota of his ability to operate.

These two constitutional provisions alone show the decimated position of the legislative branch, and actually represent something new in the “New Turkey.” Not even the neo-Kemalist 1982 coup constitution, despite its authoritarian, antiliberal, and antipluralist spirit, invalidated the parliament in such a massive way.

The architects of the constitutional amendments call the governmental system a “rationalized presidentialism” and believe they have improved the much-criticized presidential system in general by eliminating its supposed weaknesses (Atar 2017). They have failed to notice that instead they have abolished the defective democracy and turned Turkey into a semi-competitive autocracy. In their primitive understanding of democracy, however, they perceive the current system as a “true” democracy because the president embodies both the nation and the state. Everything he decides is for the good of the people and is legitimized by “elections.”

Once more this can be read with Schmitt, who did not regard dictatorship as a contradiction to democracy, but rather assessed it as the best form of democracy, because it directly reflects the will of the people (2010, 42). This is precisely the state of mind in Turkey after 17 years of AKP rule and it strongly resembles the authoritarian and fascist regimes of interwar Europe.

During both the interwar period and under AKP rule, therefore, a “New Turkey” was promised to symbolize a break with the old institutional order, but there is a disparity between promises and reality. While the Kemalists primarily propagated modernization, the AKP clearly called for a stronger and more capable state, promising to solve the problems of individuals more effectively through presidential decisions. However, a look at constitutional practice—ignoring all special circumstances given the two different historical contexts—reveals the establishment of an authoritarian regime in both phases. Although the new order under AKP was often narrated as an antithesis to the old Kemalist order, it re-enforced authoritarian elements that had been installed during the early years of the republic as a tool to establish itself as a single ruler. This is reminiscent of Schmitt’s above-mentioned concept of an authoritarian centralist and homogeneous nation-state.

These two fundamental characteristics (homogenization and centralization), we argue, are recurring tools for establishing an authoritarian state, both in the “new” Turkish nation-state founded in the interwar period and in Erdoğan’s proclaimed “New Turkey.” As this chapter illustrates using the example of the war against the country’s Kurdish population during the 1930s and post-2015, the establishment of a “new” Turkey in both cases came hand in hand with necropolitical violence against the state’s declared enemies, in which their identification and systematic elimination was rendered an existential necessity. Hence, in both cases, the main means of establishing a new order and holding on to power have been the securitization of the Kurdish issue. By no means did normal circumstances lead to the establishment of institutional orders, but rather a state of emergency in the Schmittian sense: exceptional situations in which violence against perceived enemies of the nation and state was a central ingredient (Schmitt 2015).

The Creation of an Old-New Enemy of the State After the June 2015 Elections

The surprising 2015 electoral success of HDP, a left alliance that emerged out of the Kurdish political movement in Turkey, caused a crucial setback to the government’s plans to put in place constitutional amendments introducing the authoritarian so-called presidential system (Burç and Tokatlı 2019). In response, techniques to normalize emergency rule by routinizing executive decrees and eliminating the role of the parliament as an arena for deliberation, restructuring state apparatuses, re-securitizing the Kurdish issue, as well as using body politics as a tool for power preservation (Bargu 2016, 2018), were enhanced as methods to deepen the authoritarian state and to reiterate the nation as ethnically Turkish.

While during the interwar period, a homogenous and superior nation was invented to consolidate the newly established state, after the June 2015 elections, the return to a regressive definition of the nation came as a reaction to HDP’s novel vision for Turkish politics. The party’s democratic strategy was to circumvent the authoritarian character of the state with grassroots structures built by a pro-peace, pro-women, pro-worker, and pro-minority alliance of systematically marginalized groups, such as Kurds, women, leftists, Alevis, Ezidis, Armenians, and LGBTQ+ individuals (Burç 2019b). HDP, coming from a long tradition of Kurdish parties banned shortly after their foundation, successfully reached out to a non-Kurdish electorate and advocated the counter-hegemonic model of “democratic nation” to replace the hegemonic paradigm of an ethno-religious nation-state (Burç 2018, 2019a; Güneş 2017).

The party’s strategy directly challenged the Turkish state’s status quo in general and the hegemonic physiognomy of AKP rule in particular. The counter-hegemonic project proved successful during the general elections in June 2015, where the AKP failed to gain at least 330 seats, hence a constitution-changing majority (Tokatlı 2016).

Restoring its hegemony therefore became the main political objective of the ruling AKP in the post-2015 period, which resulted in a reemphasis on the politics of exclusion, racialization, and securitization (Burç 2018; Tokatlı 2019b; Yılmaz and Turner 2019). Under the conditions of ideological challenge and electoral loss, the AKP government narrated a scenario of emergency, in which the HDP was portrayed as the main threat to the sacrosanct Turkish nation-state in order to realize the autocratic vision for a “New Turkey.” Active attempts to criminalize the party and collectively punish its supporters became integral to the regime-changing ambitions of the government, which culminated in the declaration of the state of emergency after the controlled coup d’état in 2016. While the AKP government has been steadily replacing Kemalist hegemony in fostering religious identity and cutting the power of the secularist branch within the military, the extent to which methods of building a “New Turkey” resembles Kemalist rule needs delineating.

The Politics of Turkishness and Necropower

The rise of a nationalist state in Turkey, as in other nationalist movements in interwar Europe, was closely linked to the emergence of ethnicist Turkish nationalism as a political and nation-building force. Scholars argue however that despite the rise of Turkish nationalism, the legacy of the Ottoman Empire’s millet system of ethno-religious identities, effectively shaped Turkey’s understanding of citizenship (Çağaptay 2003). Some scholars even claim that this ethno-religious signifier of who belongs to the nation and who does not has been recurrent throughout the country’s history (Yeğen 2004).

Mesut Yeğen argues that citizens in Turkey were divided into three realms of citizenship: those who inherent Turkishness by birth, those who can be assimilated into being Turkish, hence prospective-citizens, and those who, even if they wanted to, shall remain outsiders. The possibility of assimilating into Turkishness therefore was only granted to members of the Muslim community, as Turkishness was based on a shared religious identity. The legal establishment of minority rights only for non-Muslim yet indigenous populations, such as Armenians, Greeks, and Jews, as well as the national exchange with Greece in 1923, exemplify how, despite the official doctrine of secularism and universal citizenship, in practice citizenship was shaped according to ethno-religious determinants.

Legislation passed after the establishment of the Turkish nation-state demonstrates a blend of both jus soli and jus sanguinis approaches to citizenship (Çağaptay 2003, 605). This caused a situation in which the non-Turkish yet majority-Muslim community of the Kurds were subjected to top-down assimilation, neither considered inherently part of the Turkish—ethnic—nation, nor complete outsiders, hence in Yegen’s (2009) words were “prospective Turks.” As a consequence, Turkification policies became the main driving force of the nation-building process, which culminated in violent and necropolitical oppression, particularly in Kurdish-majority areas that resisted the state’s assimilationist agenda.

Necropolitics has been widely conceptualized as biopolitical forms of violence within the context of colonial rule, wars, and massacres as deployed by state power to preserve and perform sovereignty (Bargu 2016; Butler 2004; Foucault 1997; Giroux 2006; Mbembe 2003; Puar 2017). While this approach focuses mainly on the physical elimination of human life or the reduction of lives into “living deads,” we argue that necropolitical violence against the Kurdish population has been an inherent tool of power consolidation in both interwar and post-2015 Turkey.

Power consolidation under Mustafa Kemal as well as Erdoğan was achieved through the (re)creation of the imagery of a homogenous and uncontested Turkish nation, in which certain populations that resisted were defined as a threat to the integrity of the nation-state and rendered disposable. Recalling what Mbembe calls the creation of “death worlds” as a consequence of modern sovereignty, we argue that in both interwar and post-2015 Turkey the politics of (social) death were put into practice in order to effectively limit democratic potential and reinforce the authoritarian trend of Turkish politics, leading the latter always closer to a form of dictatorship that by virtue of its ability to establish the rules to its pleasure and interest has been reinstating the long-standing tendency of driving necropolitics against the Kurdish population. The deepening of the authoritarian state during both the first foundation of the Turkish republic and the so-called second foundation under AKP was therefore justified through performed necropolitical violence. The violent re-securitization of the “Kurdish Question” after a non-violent period of peace building measures between 2013 and 2015 needs to be highlighted under this premise as the existence of an unsolved “Kurdish problem” facilitated the power grab after the electoral defeat of the ruling AKP in 2015. Similar patterns are observable during the interwar period, when a newly born nation was consolidated by the performance of necropower against resisting rural areas mainly populated by Kurds.

Kurds in Old-New Turkey: Discriminated, Displaced, Dispossessed

Sur is a district in Turkey’s southeast, a UNESCO world heritage site and part of the Kurdish-majority city Diyarbakır, which was among the first areas exposed to round-the-clock military curfews after the June 2015 elections.4 When, in December 2015, the first photos of Sur broke through the news embargo imposed by the government, the extent of destruction was partly revealed as demolished buildings, houses riddled with bullet holes, raided shops, dead bodies on the streets, destroyed churches and mosques in the city’s historic center.5

Shortly after the June 2015 general elections, on August 11, President Erdoğan declared the end of the precarious, yet promising peace talks with the PKK (Kurdistan Worker’s Party). The breakdown of the peace negotiations was followed by a state-orchestrated political lynching campaign against Kurds, oppositional voices, critical media outlets and most of all against the left alliance HDP that had become a popular advocate of a democratic solution to the Kurdish Question (Çalışkan 2018, 22). HDP’s soaring societal support and electoral success were considered an immediate threat to the constitution-changing plans of Erdoğan and challenged the core principles of Turkish nationalism.

The government launched so-called cleansing operations against supposed PKK members after the June 2015 elections; however, since these military operations were carried out in all Kurdish-majority cities where the HDP came out as the strongest party, it can be argued that the re-securitization of the Kurdish Question effectively targeted Kurdish civilians in an act of collective punishment for deviant electoral behavior. The imposed politics of war after the June elections in 2015 amounted to a total of 4551 deaths counted since the 20th of July 2015, of which 478 were civilians and 223 individuals of unknown affiliation between 16 and 35 years old (International Crisis Group 2019), entire districts destroyed, and a significant displacement of the local population.6

State violence against predominantly Kurdish-populated areas has been a regular feature of the modern Turkish state; the developments in the HDP strongholds, in particular the historic city center of Sur in Diyarbakir, draw many parallels to how Kurdish-majority areas were subjected to similar policies during the interwar period. Turkey during the 1930s became a strong case of Joel Migdal’s definition of a “cohesive state.” He asserts that those states with a high degree of integrated domination, hence a power balance between state and society, as well as within the state, are guaranteed to be successful. Integrated domination therefore is when the state manages to uphold full decision-making autonomy, which stands in contrast to “dispersed domination,” when neither state nor society have the ability to implement (Migdal 2001, 126ff.). Integrated domination in interwar Turkey resulted in all kinds of measures for Turkification, without any significant pushback from within the state nor from majority society.

While still a state-in-formation in the early 1920s, the 1930s showed how different parts of the state and society already worked in congruence and therefore were able to exercise effective power collectively, which ultimately expressed itself in the amplification of oppression against all perceived threats to building the imagined nation-state. Scholars like Nicole Watts (2000, 9) even argue that Turkey possessed the highest degree of “integrated domination” in the twentieth century during the 1930s up until the late 1940s, when slowly parts of the state were pulled in different directions, becoming “dispersed.”

Assimilationist policies in the early republican years demonstrated how an ethno-religious category of Turkishness was considered national identity and deemed a significant aspect of state security. Turkification, assimilation, and forced relocation from the Kurdish-majority region, therefore, were perceived as security measures for territorial and national integrity. The case of Dersim, a Kurdish and Alevi region that rose up in 1937 against state oppression and was violently crushed in 1938 (Bozarslan 1988),7 illustrates how necropower against the Kurdish-majority population was already a tool in interwar Turkey, used to consolidate state authority in nation-making . Borrowing from the methods of the interwar period, the AKP government followed a similar strategy to narrate its electoral and political nemesis as a threat to national integrity and state security by re-emphasizing the monocultural core values of the Turkish state during the 1930s.

Resettlement laws were at the heart of assimilationist policies during the 1920s and 1930s (Ülker 2008). While the AKP government did not issue any such resettlement law, it did reveal a 10-step “anti-terror action plan” aimed at repairing cities destroyed under siege, which involved compensation payments, government consultations with village guards that function as pro-government Kurdish militia, as well as the construction of bulletproof security towers in urban districts. The government’s concept of war, which included a post-operation master plan, can be considered as an attempt to tear apart residents from their historically inhabited spaces, enforce economic dependency, and create obedient citizens crushed into submission. Then-Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu stated when presenting the action plan on the 5th of February 2016: “We will unite the nation’s conscience and wisdom with the state’s reason. All differences between the nation and the state will be entirely eliminated and we will have an understanding of uniting and integrating the nation” (Cumhuriyet 2016).

About the same time, pro-government media outlets headlined “Terror needs to be responded by TOKI” or “Back to work TOKI” (Siyasi Haber 2015). TOKI is the abbreviation of the “Mass Housing Administration,” which is the state housing body that has been operating directly under the prime minister since 2003. Despite being an active public enterprise officially, TOKI has become essentially a large privatization agency that administers the sale of public properties and buildings to private commercial parties; hence, public lands are being used as the main source of capital for mostly luxury housing projects that are being developed by selected contractors (Işıkkaya 2016).

The demolition of Sur had already begun in 2011 after Erdoğan declared new projects for Diyarbakır to be implemented by TOKI to make it more attractive for tourism. However, in 2013, construction works were stopped by local resistance, mainly mobilized by HDP-run municipalities. The AKP government is well known for neoliberal policies driven by profit-based construction. In the case of cities like Sur, the novelty in comparison with necropolitical violence was to build new mass residencies in city outskirts, to offer loans at a reduced rate to displaced residents, and to offer employment opportunities, hence creating a new relationship based on economic and political dependency between impoverished Kurdish citizens and the Turkish state.

The AKP government thus intertwined economic objectives and profiteering with necropolitics and assimilation. Practices of social, economic, and demographic engineering to achieve political gains, however, go back to the founding years of the republic. Integrating and homogenizing dissident regions into a common cultural stream by invading traditional spaces, deconstructing them, and creating new, controlled ones has deepened the authoritarian state through necropower against Kurdish people. After the Dersim massacre of 1938, the remaining Kurdish population was redistributed to other cities by the state.8 Resettlement policies in the form of laws passed during the 1930s, in the making of a new nation-state, or forced relocations as in the case of post-2015 Sur, exemplify state policies to domesticate those who resist homogenization . If we assume that landscapes are transformations of ideologies into a concrete form, where identities are created and reproduced through spaces, the Dersim massacre and contemporary siege politics in Sur illustrate the state targeting spaces known for dissent and resistance. After the military operation in Dersim in 1938, the Kurdish-Zaza populated city was renamed under Turkification policies into Tunceli, which translates as “iron first” (Bruinessen 1994).

Almost one hundred years later, the Turkish military shelled public squares, monuments, street walls, residential areas, and historic buildings such as churches and mosques in the historical center of Sur, which had previously been restored by the then-HDP municipality as part of their political campaign to create a counter-hegemonic space of peaceful interfaith and interethnic existence. While during the interwar period, resettlement laws, and thus systematic depopulation, were enacted to pacify regions disobeying violent assimilation, under the AKP in the post-2015 period, de facto depopulation caused by a staged war in the inhabited city center followed by promises of cheap housing provided by the state in the city’s outskirts seem to be contemporary attempts at the violent pacification of resisting populations within the authoritarian state.

Conclusion

With the centennial anniversary of the Turkish state approaching, the question to what extent constitutional changes under AKP rule comprise a new founding of the state or demonstrate a return to the long 1930s has become increasingly pressing. Despite a strong narrative of “breaking with the old,” this chapter shows the continuity of necropolitical violence as a tool to consolidate the nation and the state’s authority in times of contested power. From a comparative perspective, this means that although the AKP presented itself for a long time as an antithesis to the “old” Kemalist order—and was also presented as such by others—they adopted relevant Kemalist practices from the early years of the foundation, especially the 1930s, such as the (re)emphasis of the republic’s default settings one state, one nation, one flag, one language. We showed that this had two major consequences in both periods: (1) the homogenization of society, and (2) the centralization of state power. This required the use of extensive state power that, according to Schmitt, is legitimate when the state is in danger. Ultimately, there is a major difference between the two phases. While an exceptional situation after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire was obvious back then, the AKP had to invent such a threat as it is only on the basis of a concrete danger that the Schmittian state of emergency can be proclaimed. In addition to the supposed putschists, Erdoğan has identified the Kurds in general and the HDP in particular as a domestic threat to the state and has been taking violent action against them since the June 2015 elections. Again, the instrumentalization of an “enemy of the state” does not break with the old Kemalist order, but rather demonstrates a return.

Deepening the authoritarian state through homogenization and centralization, as we have shown, have been the main characteristics in both interwar Turkey and in the period after 2015, despite ideological differences between the Kemalist and Islamic political traditions. In both cases, the securitization of the Kurdish issue in the form of creating (social) death worlds, the criminalization of political aspirations, military siege politics, forced resettlements, pacification of resistant regions, economic dependencies on the state have facilitated the deepening of authoritarianism embedded in the narrative that rendered the establishment of a new order necessary to protect national integrity.