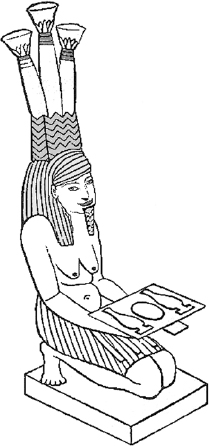

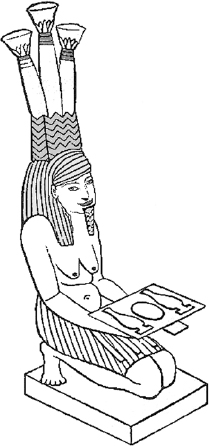

Hapi, the god of the inundation (after Budge).

Ancient Egypt and Papyrus, the Eternal Marriage

Where the Eastern waves strike the shore . . . or where the seven-mouthed Nile colors the waters, . . . whatever the will of the heavens brings, ready now for anything . . .

—Catullus, 61–54 B.C.

A resource treasured by the kings of Egypt, a prince among plants, a giant among sedges, and a gift of the Gods, the papyrus plant has been with us since the dawn of civilization. It allowed Egypt to be papermaker to the world for thousands of years and in doing so ruled the world in the same fashion that King Cotton ruled the South, the demand being met exclusively by the papyrus swamps of Egypt where it grew at a phenomenal rate.

Where did papyrus come from? To an early Egyptian this question was so obvious he need not say a word; he could simply point to a relief or a statue of Hapi, the god of the Nile inundation. This shows a seated, blue-colored, chubby man with pendulous breasts, a Pharaoh’s fake beard, and a belly hanging over his girdle. Bizarre, yes, but in a way not entirely foreign to some of us who are entranced by that most impressive Hindu god, Krishna, who was blue-skinned, said to be the maximum color in nature as in blue skies, oceans, lakes, and rivers, thus an appropriate color for special people.

Hapi, the god of the inundation (after Budge).

What I really find striking about him is his crown, which looks like a large clump of papyrus growing from his head.

The popular notion was that the plant was a sacred gift, much like the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden. In reality, papyrus came to us, as did many flowering plants, after a long stage of evolution from primeval Jurassic ancestors. It had already been established in the Nile Valley and elsewhere in Africa for thousands of years before the early settlers arrived. The important thing was that these settlers (see frontispiece) recognized papyrus as a good thing and fell in love the minute they saw it. They had come to the Valley because of the river, and they stayed on because they wanted no more to do with the Sahelian droughts of 6000–5000 B.C.

In the Nile River Valley they found a permanent sustainable existence, a part of which was the swampy terrain, a water world made up of quiet pockets of water and patches of waterlogged soil scattered throughout Egypt. And there, growing in the flooded areas, was Egypt’s new partner, papyrus, a viable hunting preserve, a source of reed for boats, housing, rope, and crafts, and above all an eye-catching part of the landscape.

After having evolved over millions of years, papyrus could be counted on to produce a swamp community that was in equilibrium with itself and a species that was perhaps more extensive, more useful, more efficient, and more luxuriant than anything seen today, because at that time the air, soil, and water quality were almost untouched, unspoiled. Thousands of years in the future, the ancient Egyptian would disappear and the eternal marriage would be dissolved against all reason, and afterwards, like some brave widow, papyrus would carry on, serving different masters through the years—Persians, Macedonians, Greeks, Romans, and finally Arabs, all of whom would use her in turn. Yet despite everything, she stayed green, lush, fragrant, and self-contained until the very end.

As Herodotus once famously noted, “Egypt is a gift of the Nile,” and so also were the swamps and marshes that formed in the backwaters of the early river, swamps which served as a natural larder with fish thriving in swamp pools year round and birdlife for the taking. These swamps developed in the floodplains (or “upper Nile”), then as soon as the river deposits changed from sand to silt they spread downstream into the delta (or “lower Nile”).

That change in the delta coincided with the migration of people from the Sinai who, like those of the Sahara, were also escaping droughts.

The water of the main river and floodplain averaged about 2 miles in width and was hundreds of miles in length (570 miles from Thebes to the sea) and provided a mighty internal highway to allow the development of Egyptian civilization. This could not have been possible, according to Fekri Hassan, Petrie Professor of Archaeology at the University College, London, without riverine navigation, which requires a boat. Yet forest trees and wood being in short supply, and carpentry skills lacking, they turned to papyrus. As Steve Vinson, an expert on Egyptian boats, pointed out: “It is difficult to believe that there was ever a time when humans failed to take advantage of the ubiquitous papyrus to build rafts or floats.” Thus evolved, in those early days from 6000 B.C. onward, the reed boat, which must have been a godsend to a hunter-fisher-gatherer.

The Egyptian wasn’t alone in this discovery. In those days, throughout several river deltas in the arid world, and the lake cultures in treeless high altitudes, reeds were used to build boats, houses, and everything that made life easier while the early families established themselves in these regions.

With time it became difficult to give up life on the Nile because here they found whatever they needed, and they grew accustomed to the lack of rain and the constant presence of water in the river. They also liked the twelve hours of bright sunshine every day and the regularity of the annual flood.

And soon it was 3100 B.C.—the point, we are told, when civilized history begins. Now improvements in agriculture and irrigation follow, wooden boats under sail are seen on the Nile, bountiful harvests are common, papyrus paper shows up, kings and pharaohs ascend thrones in succession, and immortality is now felt to be a certainty and yours for the asking. If you hankered after enduring fame, civilization was just the thing, and it had arrived to stay. Is it any wonder that the Egyptians looked for ways to live securely and forever in this paradise?

Their largest concern was inundation. To the believer, Pharaoh guaranteed it. After all, wasn’t he a god on earth? The annual flood was as certain as the daily miracle of sunrise that followed his morning invocation. To the more skeptical residents of the valley, heartaches, headaches, and sweaty palms developed each year at springtime when they wondered what was to prevent the inundation from being a bit too much or a bit too little.

If it was too low, a drought developed that hammered them for the rest of the year. If it came in excess, the flooding would wash out dikes, retaining walls, berms, mud-brick houses, and anything not nailed down. Years of back-breaking work would disappear in moments.

“Please, Hapi, just 15 cubits (25ft), that’s all we need” became a most important plea as the years went by, and in that way the overweight, blue-colored, effeminate, easy to laugh at, solo god came into his own.

The Pyramid Texts suggested that his wife, Wadjet, had given birth in the delta to the first papyrus plants and presumably Hapi was the father. This was an appropriate beginning because with time the major papyrus swamps came to be synonymous with the delta. One of several deities associated with that part of Egypt, Wadjet’s name was written using the heraldic plant, which became the hieroglyph for Lower Egypt (so named because it was downstream).

Hapi had a second form that represented southern or Upper Egypt (upstream) and for that reason he had a second wife. The two forms of Hapi commonly used on tomb paintings or on monuments proclaimed the fact that the pharaoh of the moment controlled both parts of the country.

Wadjet means “the papyrus-colored (or green) one,” which was also the general name for the cobra, appropriate for a pre-dynastic snake goddess, though the reference to green is not clear. The only green snake in Egypt would be the asp, a lime-green snake of Cleopatra fame but a snake that was imported; the native cobra is mottled gray-brown or black.

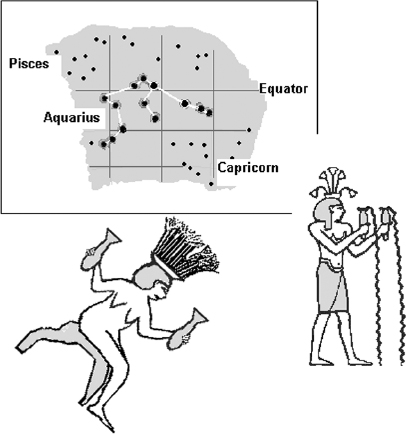

Thus, Hapi was an ancient and powerful deity who drew even more power through wives like Wadjet who in turn was connected to the forces of growth. It was later revealed that Hapi was a son of Horus and therefore a grandson of Osiris. But such lofty connections seem not to have helped much, as he had no temple and was set apart from the other gods. Though worshipped separately, he remained one of the most powerful because he controlled the lifeblood of the country. And you can see him on almost any night in the constellation Aquarius, visible in autumn in the Northern Hemisphere and during spring in the Southern Hemisphere. When the sun passes through Aquarius, or Hapi, or “Waterman,” the wet season begins. He is thus the harbinger of floods and spring rains. In ancient Egypt his constellation was pictured as himself pouring water from two jugs, symbolizing the start of the inundation. In the zodiac of the famous ceiling relief in Dendera, he is shown in two forms: one with a standard crown, and the other with a dense mass of papyrus, almost a small swamp, on his head.

Several forms of Hapi as Aquarius in the zodiac at Dendera.

True to the concept of immortality, Hapi popped up in the international news a few years back when a major exhibit of sunken Egyptian treasure went on the road. The exhibit contained spectacular artifacts unearthed by Franck Goddio, the undersea archaeologist and founder of the Institut Européen d’Archéologie Sous-Marine (IEASM), taken from the waters of Alexandria and other ancient city ports. The exhibit drew a crowd of 450,000 in Berlin.

The show went on to a bigger and better reception at the Grand Palais in Paris and was the subject of several feature stories in the leading French newspapers and Paris Match. Next stop was Bonn for more attention and a feature in Der Spiegel, following which it closed in January 2008, when the pieces were scheduled to be brought back to Egypt to make up a permanent exhibit in Alexandria.

One of the leading items of this collection is a 16.5ft statue of Hapi, the largest free-standing sculpture of an Egyptian god in existence, now the object of attention by millions of people; and on his head, still proclaiming to everyone his magnificent gift to the world, are three stems of papyrus.