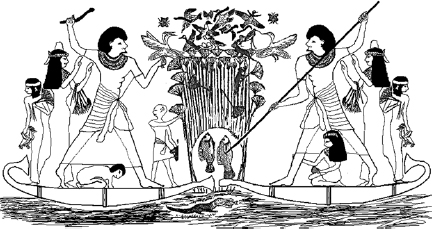

Hunting in a papyrus swamp (Egyptian tomb painting).

On the wall of a tomb in Egypt, I saw a painting which I remember thinking at the time was unusual. I had seen others similar to it in the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and in books on Egyptian art, but none were quite like this. The painting shows an Egyptian man drawn twice as large as the papyrus skiff in which he is standing. The hunter is tall, confident, and balanced in a way that says he knows exactly what he is doing. There are others with him: his wife, children, and perhaps other household members, drawn much smaller and looking quite vulnerable. A small girl clutches at his manly legs while he appears twice in the painting, simultaneously on both sides of the swamp, ready for anything.

This was several years after my introduction to papyrus swamps, and I could now appreciate the detail and accuracy of the ancient artist who had captured this scene. As someone in the crowd of tourists clustered around the painting remarked, “It looks almost like it’s frozen.”

Hunting in a papyrus swamp (Egyptian tomb painting).

In the air above the hunter are throw-sticks caught at the moment when everything is happening. A dense flock of birds has just been flushed out of the papyrus umbels by beaters; some are still hesitantly perched, trying to decide whether to take flight or not. A few butterflies flit about as the undecided birds stare at their fallen colleagues, whacked by the throw-sticks. In the water are all manner of fish. A wily crocodile clamps its jaws tightly around one, while the mirror image of the hunter spears a world-class tilapia on the other side of the swamp.

Everyone in the picture has something to show for this man’s effort. Ducks, cranes, and other stunned birds are being taken up, while the women gather papyrus umbels and water lilies, perhaps for decoration at home or for wreaths or temple offerings. Papyrus was a favorite for all of that. If you look closely you can even see bird eggs ready to be plucked from nests perched on the papyrus umbels. But the hunter better be quick, because there is also a wild cat and a large rodent with eyes focused on those same eggs.

The tall stems of papyrus lean out toward this lithe, graceful hunter as if bowing in adoration, a reflection perhaps of the intimate knowledge that ancient Egyptians had of the habits and properties of plants and animals, the same organisms to which they paid homage in the temples, yet took their lives without regard in the swamps.

The ancient hunter reminded me of a young Louisiana swamp ecologist I’d met at a seminar on wetlands in the southern USA. He said he loved paddling his pirogue into a backwater region not far from home, where he never went without a light rifle, some tackle, and his dog. I imagine his boat was not all that different from the papyrus skiff shown. He would only have to slip on a fancy Egyptian necklace and a wig and he’d be a dead ringer for that 4,000-year-old high-born swamp crawler.

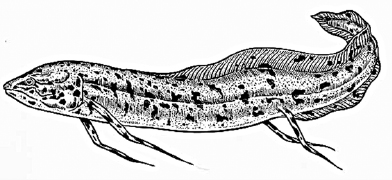

In all this, I saw again how papyrus creates its own unique and interesting habitat. In ancient days in the Nile Valley, aquatic birds swam or waded along the edges in search of the plentiful aquatic life, water insects, amphibians, aquatic weeds, plankton, and small fish that thrived there. Land birds perched in the umbels while others settled on stems gracefully leaning out over the water; some even wove nests there. Papyrus swamps, in ancient days as well as today, provide refuge for twenty-two species of Palaearctic and Afro-tropical migrant birds. They are also the preferred breeding grounds and habitat for the Papyrus Gonolek and Papyrus Yellow Warbler, and the feeding grounds for wading birds, including the globally vulnerable shoebill known in scientific circles as Balaeniceps rex.

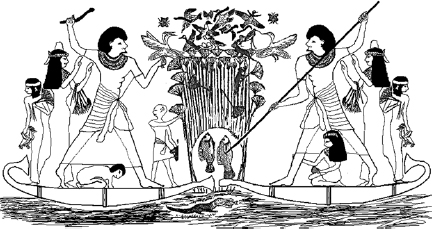

The shoebill is an extraordinary bird; it is above all things a throwback in history. A massive creature about 3–4ft tall with bluish-gray plumage, it is a shock to see one for the first time. Watching one wading at the edge of a papyrus swamp gives the impression that nothing has changed in the intervening millennia. In fact, the shoebill has been with us for the last 30 million years. When the bird guidebooks say “it looks prehistoric,” they are certainly telling the truth.

The most obvious feature of this bird, which lives almost exclusively in papyrus swamps, is of course its distinctive broad bill which does resemble a shoe, in particular a greenish-brown size-ten slogger, of which I own a pair. Those now sit in my study, reminding me of the first time I ever saw one of these birds. Its bill ends in a formidable hook, which it uses to pull apart the unlucky lungfish on which it feeds. Once seen, the shoebill is never to be forgotten, and it continues to baffle. Although it was formerly called a “whale-headed stork” (hence the Latin name), taxonomists are still undecided if it is a stork, pelican, or heron. Unfortunately this bird is now rare. Like papyrus, it has survived only by inhabiting regions that were left behind by history but are now being developed, and it is running out of places to hide.

The shoebill, formerly the whale-headed stork (after Brehm).

Of the few mammals found in a papyrus swamp, the most unusual, outside of man, is the sitatunga, a small, shy antelope (Tragelaphus spekii). It has an obvious adaptation to papyrus swamps in that its splayed hooves are extremely narrow and long, up to four inches in length, with extended false hooves. It is well and truly adapted to this environment because with its mini-ski type feet it can walk from rhizome to rhizome, just as I did. Perhaps they were the means by which early African people happened onto this trick. Another useful habit of the sitatunga is that it is an excellent swimmer, even in deep water where they have been known to submerge themselves completely, and occasionally even sleep, with only their nostrils above the waterline.

The sitatunga, African swamp antelope with splayed hooves (after Haeckel).

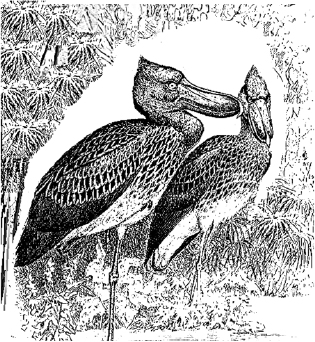

Along the edges of the ancient and modern papyrus swamp, and also in the small ponds inside, we find fish that are attracted to the swamps because of the refuge provided from predators. Nowadays that would be the Nile Perch, which has driven many fish species to extinction in lakes such as Lake Victoria. Among these fish are the snake-like lungfish (Protopterus annectens), which is the most unusual of the lot as it is a faculative air breather that can live out of water for many months. It does this by using a pocket in its gut that is lined with thin-walled blood vessels which serves as a lung. The lungfish also possesses gill arches with gills; thus it can breathe in either air or water, which is a useful adaptation for marshes and swamps (which dry occasionally) and illustrates a transition in the evolution of creatures breathing water to creatures breathing air.

The lungfish is normally preyed upon by the shoebill and other wading birds that spot it swimming in the water just above the mud. It is vulnerable even when it is at rest inside its mud burrow, as Africans on occasion dig up the fish, along with the whole burrow. They store it intact in a corner of their hut until they feel the need for fresh fish—a useful practice in remote areas where refrigerators are still rare.

Air-breathing African lungfish (after Govt. Queensland).

The ancient Egyptians knew all about these strange creatures and the unique qualities of the papyrus ecosystem. They were enchanted by it, and they worshipped many of the animals and plants that were found there, unlike the Greeks and Romans who conquered Egypt in the last days of its majesty, when it had grown weak and tired of its own inept dynasties. The new rulers were interlopers on the world stage of ancient civilizations and not familiar with the exotic ecosystems they found in Africa. They thought the beatified organisms of the Egyptians peculiar, or most strange to say the least. Plato swore by “the Egyptian dog” or “the barker” (Anubis, the jackal-headed Egyptian god of the afterlife) in place of proper Greek gods. The Greeks were more circumspect than the Romans, who were outright scornful and thought the Egyptian practice of mummification of thousands of ibises, crocodiles, cats, bulls, and dogs was bizarre. Imagine the repugnance of the cultured men of Rome when they saw the paintings and statues of the crocodile-headed Sobek, patron god of the army, and Ta-Urt, the goddess of fertility with her crocodile tail, pregnant-looking hippopotamus body, and hippo head.

Who does not know, Volusius, what monsters are revered by demented Egyptians? One lot worships the crocodile; another goes in awe of the ibis that feeds on serpents. Elsewhere there shines the golden effigy of the sacred long-tailed monkey. (Juvenal. 100–127 A.D. Satires XV)

As for the sacredness of papyrus, that was a concept beyond the pale of the conquerors. They hardly thought of papyrus in any way other than as a commercial enterprise: the plant used to make paper. To them Egypt was a granary, a plantation with little to offer the civilization they knew. They left records of their disdain on bits of papyrus paper in the personal correspondence collections found at Oxyrhynchos in the 1800s.

Botanists today are no strangers to tropical vegetation; little surprises them among the exotic plant types found in tropical locales. But newly arrived visitors in the tropics are often dismayed to find the local plant life vaguely familiar. They are dismayed because on closer inspection they see that many are simply overgrown houseplants! The potted plants they took for granted back home—the philodendron, dieffenbachia, croton, oleander, and euphorbia—are all here, growing unfettered, almost scary in their untamed luxuriance.

And papyrus? Well, it’s no different. In the ’70s, as I looked out over swamps that extended for miles and miles across meandering valleys and covering whole sections of lakes and banks of rivers, I had to remind myself and others that it was a sedge. What does that mean? To most gardeners, sedges are lawn weeds. Every time you cut your lawn, depending on its condition, you could be mowing down hundreds of sedges! But in Africa, papyrus is a tall, robust, overpowering sedge, a 15–20ft giant that is almost as absurd to Western eyes as the other overgrown houseplants.

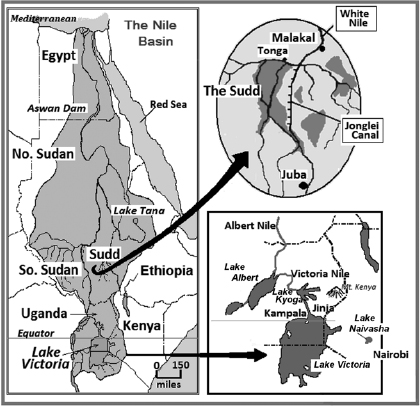

Papyrus reaches its maximum growth potential in the equatorial regions of the Great Lakes of Central and Eastern Africa. It grows in standing water over vast expanses of the Southern Sudan and along the rivers of this region (Map 1, p. 17). Riverine papyrus swamps are found on the Victoria Nile, the Nile that flows from Lake Victoria through the Lake Kyoga swamps and into Lake Albert in northwestern Uganda. All along this part of the Nile one can see lush growths of papyrus on both banks of the river, with tall plants producing enormous umbels that wave gently in the breeze like small green clouds. An impressive sight when seen from a small boat, and familiar perhaps to viewers of the movie The African Queen, part of which was filmed in this region.

MAP 1: Nile catchment, Sudd area, and Lake Victoria.

My favorite line in that movie is spoken to Hepburn by Bogart from the top of the mast: “Nothing but grass and papyrus as far as you can see!”

These riverine papyrus swamps lie for the most part inside national parks and are therefore protected. As the river traffic is light and the population dispersed in these regions, the swamps will probably not change much in the future. From the air they resemble light green bands that run along both banks of the river for miles. Inside such swamps we find that the leading edge is a floating matrix or mat of papyrus that grows out onto the river. It is anchored to the shore by plants growing on wet mud along the flooded shoreline, and the rhizomes are interconnected in the matrix. If the river were to slow down or become silted up, papyrus would in fact grow right over it from bank to bank, as it does in river valleys and swampy ravines in many places in Uganda. Under those conditions it is capable of extending over a large region, since papyrus is capable of growing up to two inches a day. It reaches an annual growth rate of thirty to fifty tons dry weight per acre per year, a rate that puts papyrus in the same class as bamboo and other fast-growing grasses and ecosystems, such as the tropical rainforest. The secret behind its impressive growth is its C4 plant status which, in botanical terms, means that it falls among the elite in terms of its photosynthetic pathway. Only about 7,600 species of plants—about 3% of the 250,000 known species of plants—use C4 carbon fixation, the pathway allowing the fastest growth rate among vascular plants.1

In addition to fast growth, it does not seem to be much affected by disease, and it is seldom eaten by animals, other than the sitatunga or starving cattle or goats. Its protection from disease and the parasites that carry it derives from the fact that the upright stems have a tough green skin, a skin that as we will see serves admirably for making rope.

The morphology of papyrus is straightforward and typical for a sedge; each upright stem, or culm, appears and grows upward from the tip of a horizontal stem, or rhizome. The upright stem expands at its top and spreads out into a large tuft of slim, flowering branches, or umbel. The base of the stem is closely sheathed in scale leaves, and the umbel at the top of the stem is enclosed in scale-like bracts prior to opening. The stem is triangular in cross-section, a distinctive feature that sets the sedges apart from grasses. Collectively, swamp grasses, grass-like plants, sedges, and rushes are all called “reeds.”

Papyrus grows on wet mud at the water’s edge, where young rhizomes tend to grow over older ones; the whole mass so created, along with a layer of peat, then spreads out over the water as a floating mat. This is possible because the plant is equipped with many air spaces in the stems that provide the necessary buoyancy. On large African lakes or deep rivers, it will form a substantial floating swamp, with stems so tall that it is difficult to look over them unless you are on the deck of a steamer. That was the only way that Harold Hurst, a British scientist, could see elephants moving about in the shallow end of a swamp on the White Nile in 1952.

With such amazing growth potential, the question arises: Why then hasn’t it covered the globe? The fact is that it is susceptible to changes in water level, salinity, or rough wave action. Thus on wide rivers, such as the Congo, and lakes, such as Lake Victoria, large segments break off and float away from the swamp. Such islands can be a hazard to inland water shipping and the fishing industry. Papyrus also does not do well if the water level drops during drought conditions. The swamps are then stranded on dry land, at which point they dry out and die, making them very susceptible to burning and clear-cutting, a factor that has led to the demise of papyrus in farmed areas throughout Africa.

In the time of the Victorian explorers like Sir Samuel Baker, who passed through Cairo and Luxor on his way to Uganda in search of the source of the White Nile, the papyrus swamps of Egypt had been cleared for agriculture, and much of the original vegetation on the river had been replaced by a cultivated landscape. But the Nubian swamps, or “Sudd” (Map 1, p. 17), well south of Egypt, had escaped a similar fate because of their isolation. It was here that the same explorers found papyrus growing luxuriantly, and, unluckily, it was through this part of Sudan that they had to hack a path for their steamer.

The Sudd is an enormous complex of wetlands and aquatic ecosystems, ponds, rivers, lakes, swamps, and seasonally inundated grasslands on black soils. Recently surveyed with remote sensing, the Sudd was found to cover 2.3 million acres during the dry season. That would be a good measure of the extent of permanent swamp and would include ca. 1 million acres of papyrus swamp, which dominates the permanent wetlands. When flooded, the Sudd expands to a whopping 10 million acres—the size of the Netherlands.2

It is in this terrain that we find the ideal habitat of the Nile Lechwe (Kobus megaceros), an antelope with elongated splayed hooves as in the case of the sitatunga, but less extreme. This adaptation distributes the weight of the animal and allows it to spring from tussock to tussock and easily race through shallow water. But the lechwe doesn’t do so well on dry land. The total population has been recently estimated at only 30,000. That low a population number, and its restricted distribution, suggests it could easily be threatened by extinction if the swamps were to be drained.

The Nile Lechwe, along with two other antelope, the Tiang (Damaliscus korrigum lunatus) and White-eared Kob (Kobus kob lucotis), were featured in the Sierra Club video film Mysterious Herds of the Sudan: Migration of the White-eared Kob, and in the November 2010 edition of National Geographic that featured “Great Migrations.” This collection of antelopes forms the second largest group of free-ranging large mammals in Africa, second only to the wildebeest of the East African plains.3

The swamps are not easy places for large animals to get in and out of. The most common large animals in African swamps are the amphibians, such as crocodiles and hippos, but even they are relegated to the swamp edges. They are seldom seen inside the actual swamps because hippos are too large, and crocs, being cold-blooded reptiles, prefer rocky outcroppings or mud banks out in the open sun, where they can prowl the mucky shallows in search of fish among the aquatic weeds and still stay warm.

Elephants occasionally take refuge in swamps, especially in the dry season when they are attracted to the water found in the swamps of the White Nile and the Okavango in Botswana. These were the animals seen by Hurst from the top deck of a steamer, with white egrets perched upon their backs. This fondness for swamps may run in the family, as the Moeritherium, a prehistoric elephant with a flexible upper lip and snout, spent most of its time half-submerged in the primeval swamps. Modern elephants use the swamps as a refuge while they feed on seasonal grasslands nearby. The remoteness of the Sudd swamps provided protection for thousands of elephants during the last Civil War in the Sudan.

From its present pattern of growth, and considering local topography and hydrography, it is possible to paint a general picture of what papyrus swamps must have looked like in ancient days. The Nile Valley in both ancient and modern times was a free-draining region, unlike the weed-choked swampy southern region, the Sudd. The ancient Nile River channel allowed an amazing quantity of water to pass through; under such conditions it would be difficult for permanent swamps to become established except in the backwaters.

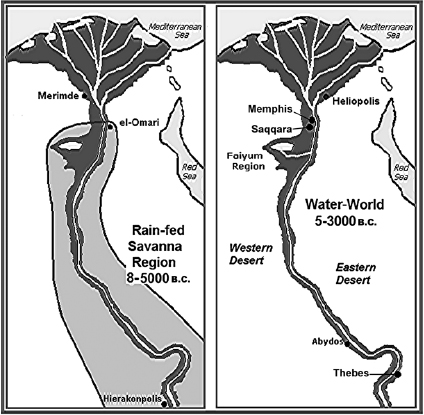

During this time, savannas were a feature of the valley. Grass-dominated, they greened up with the spring rains to provide a pasture and grain-growing soil (Map 2). Widely dispersed farming and ranching communities sprang up with lifestyles tuned to the annual savanna cycle. Towns like Hierakonpolis in the south and el-Omari in the north became regional centers where grain was harvested and traded in quantity.

MAP 2: Rain-fed savanna of archaic Egypt and the water-world.

Closer to the river, a water-based culture or “water-world” developed within the Nile floodplain. This part of the floodplain was at least half-covered by vegetation and thickets, interspersed with 3,000 sq. miles of agricultural land irrigated by the flood from annual inundations.4 And so it continued for centuries, until the summer rains began to fail. By then the rain-fed areas had begun to contract and the savannas disappeared. Now the eastern and western deserts came into being, and seemingly the good days of free range and waving fields of grain were over. During all this, the water-world acted as a natural buffer. It became a sustainable reserve as the savannas died out and aquatic resources were increasingly exploited. During the climate change toward the end of the Palaeolithic (25,000–7000 B.C.), large mammals were still part of the diet, but fish, especially catfish (Clarias), clearly became one of the main staples, along with wetland tubers.5

With time, the water-world itself was cleared, developed, and used to provide the basis for the irrigated world of pharaonic times, a period that blossomed with the arrival of water-lifting techniques.

At its height, the water-world was united during the flood by the river overflow, which spread out among the 130 natural basins of the floodplain, reaching well into the waterways of the delta.6 Unlike the brackish wadis and marshes of the rain-fed sector, which were overgrown with grass, reeds, and rushes, the water-world supported many freshwater plants and animals. It was here that tall papyrus stems were produced in quantity. This lush bucolic region was used for food collection, seasonal grazing (cattle, sheep, and goats), and craft production (boats, mats, paper, and rope), and it also yielded a year-round supply of water fowl and fish. Its center was probably Memphis, the capital established by Menes in 3000 B.C. That town, located at the juncture of the Nile and at the apex of the delta, was in a strategic position. It was a place of feverish activity, with a port, workshops, factories, and warehouses. Memphis thrived as a center of commerce, trade, and religion, and in later years also became one of the centers of papyrus paper production.

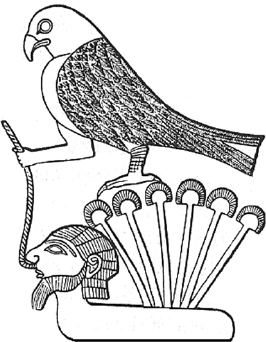

Outside the valley proper, swamps flourished in the delta and in parts of the Faiyum region. At that time, papyrus swampland ranked below irrigated agricultural land as a major feature of the landscape, but still the swamps were considered prime property and were well protected because they increasingly provided the paper and rope needed as export money-spinners that helped Egypt rule the East. On one of the few historical records of that time, the Narmer Palette, papyrus was featured over a dozen times.7 The palette, thought to be the first document in the history of the world, dates from around 3000 B.C. and commemorates Narmer (also called Menes). The earliest Egyptian king known to rule the swampy region of the delta was closely associated with Horus, who is often depicted as a falcon. On the palette, Horus is shown with a rope in his claw. He has tied up and contained the enemies of the land, typified by the head of a bearded Assyrian, ready to be delivered to the victorious ruler. Significantly, Horus is perched on a clump of papyrus umbels that represents the extensive delta swamps, which were later placed under royal mandate and considered the property of Pharaoh. Like other valuable commodities in Egypt, they became jewels in the royal crown.

Pictogram of falcon perched on top of six papyrus plants (Narmer Palette).

How extensive were the swamps of ancient Egypt? Early writers, knowing the importance the ancients attached to papyrus swamps, thought of the prehistoric Nile as just a large swamp, perhaps something like the large papyrus swamplands of the Sudan. They wanted the Egyptian Nile to match their idea of a wall-to-wall wetland. But as Dr. Karl Butzer, Professor of Geography and Environment at the University of Texas and author of the famous book Early Hydraulic Civilization in Egypt, has pointed out, unlike the Sudd, which is a permanently flooded flatland, the Nile in Egypt was only seasonally flooded; otherwise it had a deep main channel with a strong flow. Any permanent swamp would have to be located off the main channel in the areas he called “papyrus land” or expanses “. . . amid the papyrus, reeds, and lotus pads of the cutoff meanders, backswamps, or deltaic lagoons.”

Danielle Bonneau, an Egyptologist and specialist in water use in ancient times, reckoned that there were at least 49 sq. miles of papyrus swamps in the Faiyum basin, the region in which Crocodilopolis stood, one of the most fertile areas in Egypt. Bonneau based her estimate on information from ancient legal cases that were set out in old papyrus documents. She used estimates of damages and settlements made because of breaches in dikes to estimate the size of the swamps or croplands. According to another authority, Prof. Naphtali Lewis, the Faiyum region was the site of the “Great Swamp.” Lewis also noted that hardly any village in Egypt could exist without a neighborhood swamp—the plant was that important.8

Within the main river valley, two large swamp regions were located on the western bank by the Egyptologist Michael Herb. The water in these swamps must have been replenished each year when the Nile overflowed. Both regions are now filled with silt, but can be roughly estimated on maps of the floodplain. They comprised about 636 sq. miles.9

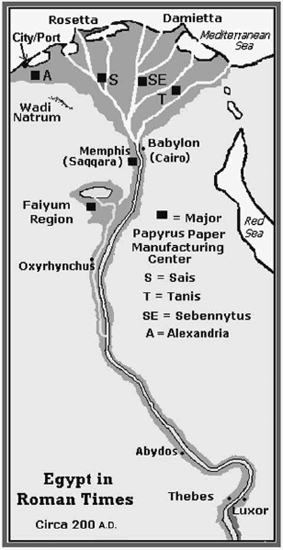

Papyrus also grew extensively within the delta, where several major centers of papermaking were located. Prof. Lewis indicated one center at Sais, and another on a spit or “tongue” of land not far from Alexandria and referred to as taenea. Throughout the eastern delta, other centers were located at Mendes, Tanis, and the ancient city of Memphis just south of the apex of the delta (Map 3, p. 25).

MAP 3: Major papyrus paper centers in ancient Egypt.

In the early days, according to Butzer, the delta region including Alexandria was sparsely populated. Swamps located there would have been very little disturbed. If papyrus swamps made up 22% of the area (the same proportion of papyrus swamps in the Faiyum region), a conservative guess within the delta would mean 1,855 sq. miles were taken up by papyrus. This suggests that the total area of papyrus from before the Ptolemys until late into the Roman Empire would be roughly 2,500 sq. miles, an area slightly larger than the state of Delaware, and an area that was the sole source of paper for the entire world for four thousand years.

Unlike food, papyrus paper was a non-agricultural product that could be exported year in and year out without regard to famine conditions. Political disturbances did take their toll and there were times of disruption in paper exports because of riots in Egypt, but the increased production in paper in the heyday of ancient Egyptian civilization was mostly due to the overseas market.

To the average Egyptian all this would be of little interest, as few in the general population could read or write. Reading and writing was the sole job and skill of scribes, who were high up in the social hierarchy. The most useful thing about the plant was not the making of paper or the importance of papyrus paper to the world, but the multitude of things that could be made from it at no cost for use around the house. Though halfa grass and palm leaf were used extensively for basketry, these had to be bought or traded for in some fashion. For the swamp dweller and people living on or near the water in need of a quickly built boat, a mat, a length of cheap rope, or even a house, it must have been a comfort to have papyrus close by, which could be used to fashion all of those things simply by harvesting the reed. It was indispensable. Truly a gift of the gods, and a plant on which an entire civilization arguably rested.