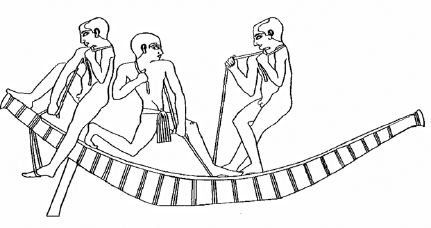

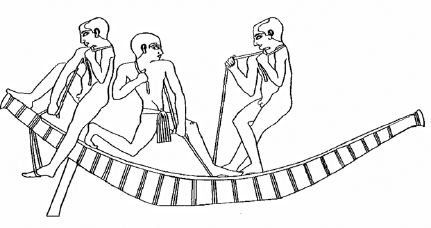

Papyrus skiff being built by tying papyrus bundles together tightly. Relief in the tomb of Ti 3360 B.C. (after Jones).

Rope, the Workhorse of Ancient Egypt

In 482 B.C., just two years after the Persian king Xerxes had put down a rebellion and appointed his brother ruler of Egypt, he assembled the largest army ever: almost a half million men on the southern side of the Hellespont. The Persian Empire controlled Egypt, northern India, Asia Minor, and southern Europe, but Greece had yet to be subjugated. To achieve this and begin his invasion of Greece, Xerxes called on his generals to build two bridges across the Hellespont.

Herodotus tells us that in carrying out his order the Phoenicians made one bridge using flaxen cables, while the Egyptians made a second from cables of papyrus. Essentially, each of the two bridges would require the use of three hundred wooden ships acting as pontoons that would be anchored and kept in line by the cables—an enormous undertaking as the strait is 0.75–4 miles wide and at times can be quite turbulent.

The famous Ancient Greece scholar Nicholas Hammond demonstrated that in modern engineering terms the bridges could be reconstructed in theory and would work in practice.

Imagine then the competition as the two bridgemasters, Phoenician and Egyptian, vied for a place in history and the heart of this vengeful king. The cables would have to be almost a mile long and each would weigh hundreds of tons! Some authors suggest that the cables were made on site, in which case the Egyptian engineers would have to ship large quantities of papyrus rope to Abydos, the Persian town on the Hellespont where the bridges would begin, and here it would be twisted into cable form. The rope used for the Egyptian cables would be of the standard three-strand variety of papyrus rope, which was then still in fashion among shipbuilders on the Nile. But the quantities required by Xerxes stretch the imagination.

A modern natural-fiber hawser cable would be two feet in diameter; for the Egyptian engineers to deliver enough rope to twist into four papyrus cables of that size would mean that about 675 miles of three-strand papyrus rope would be needed, and would have to be produced under pain of being beheaded.

Could they do it? Thousands of years before this, the typical wooden ship of the Nile required about 1,000 feet of papyrus rope in her rigging. A papyrus reed ship would need even more because the reed bundles had to be bound up. Xerxes’ order would amount to rope enough to rig about 2,000 ships, a tall order but not impossible because the ropemakers of Egypt had been in the business a long time, and they were the first in history to come up with the techniques to make rope on a mass-production basis. One good example of them at work is shown on the wall of a tomb in Saqqara on the west side of the river close to Memphis, the ancient capital (both were south of Cairo, the modern capital).

It is no ordinary tomb; it belonged to Khaemwaset, son of Rameses III, and dates from around 1100 B.C. It clearly shows ropemakers hard at work in—of all places—a papyrus swamp.

The puzzle to some people is: Why make rope from papyrus, let alone in a swamp? Also, what’s so special about papyrus with regard to rope-making in particular? There were many other fibers that could be used to make rope in those days. High-quality rope was made from the fibers of flax, leather, animal hair, or the fibrous leaf base and leaflets of palm leaves. In fact, palm leaves are still used today to make traditional rope in Egypt and elsewhere by shredding the leaflets into strips of about an eighth of an inch wide, soaking them in water, and twisting them by rolling between the palms of the hands. These are then twisted into a cord and further into a two- or three-strand rope of about half to three-quarters-inch thickness.

Although antique hemp rope has never been found in Egypt, there were other excellent fibers available from grasses found in semi-arid areas, such as halfa grasses (Desmostachya bipinnata and Imperata cylindrica). Ropes made from such material were much in demand, but often the rope that came to hand was the cheapest available: that made of papyrus. It was even used to move large blocks of stone. Dramatic proof of this came in 1942 when British soldiers digging in a quarry not far from Cairo found a block of identical size and shape to those used in the building of the pyramids. “Around this block was a length of rope, the free end of which was evidently handled by a team of men whose skeletons were also found. Under the block were traces of wooden rollers used to ease its movement to the mouth of the cave. It is thought the Nile was wider in those days, so that rafts could be brought up to the entrances of some of the caves and the stones were then loaded and floated downstream, for landing on the West bank near the pyramid building sites. In this instance, however, the cave must have fallen in, burying the occupants alive before their task was completed.”1

The rope wrapped around the block was 168ft long and made from papyrus twisted into three strands. It dates from 300–50 B.C., and a small piece taken as a souvenir by the soldiers was recently sold at auction by Bonhams for $1,000.

It came as no surprise to me to hear that the oldest intact coils of rope and the largest, longest ropes from ancient days were made of papyrus—a finding made recently by Dr. Ksenija Borojevic, Professor of Archeology at Boston University, during her study of a large cache of rope found in caves in the ancient Egyptian harbor on the Red Sea, the pharaonic port of Mersa Gawasis that dates from 1800 B.C.2

She agreed with me that in ancient Egypt, papyrus was likely the plant of choice for making thick rope in large quantity. The question remains as to whether the rope found in the cache was used by the shipwrights or whether it was awaiting export.

Although papyrus rope is not a slim, high-tensile performer, it is still quite strong and it had its uses, and because it was so cheap to make, it could be doubled up to make it as strong as linen or grass rope. That there was a market for it is illustrated by mention of it on account sheets of the day, and it had great advertisement. Theophrastus, for example, reported that Antigonus Gonatas (c. 320–239 B.C.) during the Second Syrian War won a great naval victory against Ptolemy II, and it happened that Antigonus had recently equipped his fleet with papyrus rope. Papyrus was still being used in Sicily to make rope as reported in 972 A.D., during the Muslim occupation. Ibn Hawqal, a merchant from Baghdad on a visit to the island, described a marshy area near Palermo where “. . . there are swamps full of papyrus. . . . Most . . . is twisted into ropes for ships . . .”3 and it is still used today to make rope on the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya by Luo fishermen.

It was made close to the swamp for several reasons, one being that the swamps provided fresh raw material for free. Papyrus rope can be made from crushed stems twisted together or from the skin. Each stem has a thin tough rind, or skin, that is easily peeled from the triangular stem. These green strips of skin can be further split lengthwise into even thinner strips while they are still fresh, so they can be twisted into twine, cord, rope, or even lamp wicks.4

Stems or skins of papyrus have a big advantage over the smaller segments of grass and palm because they can be up to 15–20ft long, ideal for making a fast, cheap rope. Often the green skins were available from the papermakers who were working in the same swamp.5 Since papermakers were only interested in the inner white pith that is revealed once the stems are peeled, the green skins went begging. And since millions of sheets and rolls of papyrus paper were produced every year, and every stem produced three strips of skin, it was natural for the Egyptians to use these for something. Why not rope?

With one blow they would solve two problems: how to make money off a waste by-product of papermaking, and how to produce cordage that allowed small craft and larger vessels to be built, since the rope produced in the swamp could be used directly in making the boats as well as rigging larger boats.

So all along the edges of the extensive swamps in the floodplain and the delta of the Nile, workers were hard at it. When the Egyptian engineers stood there on the shores of the Hellespont, they could be confident that they could produce, and they were certain that their product would stand up.

Papyrus skiff being built by tying papyrus bundles together tightly. Relief in the tomb of Ti 3360 B.C. (after Jones).

But not long after the bridges had been put in place, a great storm blew up and the pontoons pulled loose from their anchorage. When the bridges came apart, Herodotus tells us that Xerxes became very angry. He flew into a rage and decided to punish the culprits. He perceived these as being both the bridge builders and the sea. The former were beheaded and the latter, the Hellespont, for its role in thwarting the king, received three hundred strokes of the whip administered by royal whippers. They literally waded into the miscreant, fulfilled the king’s orders, and for good measure threw a pair of foot-chains into the sea.

Herodotus commented that this was a highly presumptuous way to address the noble Hellespont, but it was typical of the king’s attitude. A new set of engineers set about repairing the bridges. They put the cables back in place, which allowed Xerxes’ army to cross from Persia into Greece. Though their advance was famously blocked at Thermopylae, all of Boeotia and Attica fell as the Persian army laid waste to the region. In the process, Athens and the temples and buildings of the Acropolis were plundered and burned.

Who ever thought rope could be so important?

Rope was to evolve also as a factor in building the first houses in early Egypt, where it was used to bind papyrus reeds to the light frames even as it had been used to create the early boats on the Nile.

For the pharaoh, only the best quality rope was used, since the royal boats were the height of sophistication. In the Cheops Solar Boat discovered near the pyramids in 1954, halfa grass rope was used to tie the planks.6 Likewise, when rope was presented to a temple such as that of Amun-Re in Karnak, it had to be the best rope made of grass or palm fiber. But the workhorse of the nation was the everyday production from the papyrus swamps, which found uses throughout the history of ancient Egypt. Papyrus rope, twine, and cord were handy, cheap, and made money. So it is no wonder that some of the first pictures of ropemaking in the history of the world were set in papyrus swamps.