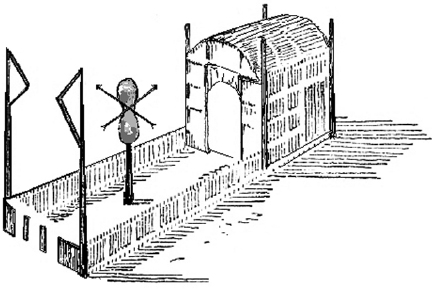

Archaic temple to Neith with a shield and arrow emblem of that god, built of light materials ca. 3000 B.C. (after Badawy).

Sacred Swamps and Temples of Immortality

In September 1911, Count Eric von Rosen rowed out to the floating edge of a papyrus swamp on Lake Bangweulu. This lake lies inside the basin of the Zambezi River in south central Africa, close to the place where Dr. Livingstone died 40 years earlier. A landing place had been cleared and cut stems laid down in a crisscross pattern to make a platform. In the near distance were a few simple huts made of papyrus. It was clear that the swamp people who lived there, the Batwa, had disappeared just moments before his arrival. The count stepped out of his boat and walked forward cautiously. At the moment the Batwa were in hiding, but he assumed they were watching him, a typical reaction of those who live in swamps worldwide. They are notoriously suspicious. The problem he faced was that if the Batwa didn’t like what they saw, they had a reputation for swift and final retribution.

He had trouble keeping his balance walking on this floating, swaying mat. It was like walking on a waterbed, and he had little time to think because he was worried about the kind of reception that might be in store for him. He tells us that “. . . at every step the ground shakes and water and mire often rise above the ankles.” It required all his attention to keep his balance. In this environment everything was in motion. He and his caravan staff complained of dizziness and the feeling that they no longer had control.

He managed to get as far as the cluster of papyrus huts when the Batwa appeared. They reluctantly welcomed him and he stayed on, living with them and studying them for some time. But once he had described their strange and watery world in his reports, he put them out of his mind.

Years later, in the spring of 1927 while he and his wife Mary, Countess von Rosen, were visiting Egypt, they were given a guided tour of the Step Pyramids in Saqqara. The site was being excavated by Cecil Firth, Chief Inspector of Antiquities. As von Rosen toured the place, he saw what many tourists have seen over the years: an extraordinary temple complex dating from 2630–2611 B.C. that is said to be the first major architectural enterprise executed in dressed stone, and the first formal architectural representations in the Western world.

Located on a wall in the House of the North are three columns, thin graceful papyrus stems made of stone, referred to as “engaged” because they are in relief, not free-standing. Nearby are other columns, also engaged, but these are fluted to resemble bundles of reeds.

Later in the tour, the count was shown a blue-glazed wall covered with faience tiles. He was astonished. The wall looked identical to the papyrus reed panels used by the Batwa to seal the front entrances of their huts. Firth then showed him a display of faience djed columns along the upper part of the wall, that mysterious Egyptian cult symbol said to represent a tree, or a god’s backbone, or a complex column, or a pole around which were tied sheaves of grain. Later on they saw a façade in the House of the South, a khaker frieze that resembled the djed decorations.

To von Rosen, all of these looked like papyrus reeds lashed into bundles of one sort or another. When he turned to Firth for an explanation, Firth confirmed what he already suspected, that papyrus reeds tied into bundles must have been used in the past for all sorts of construction, including what could be construed as the first arches, balustrades, and curtain walls, as well as the first paneled doors!

The count was beginning to see papyrus reflected in almost everything that he looked at, and in his mind he saw the Batwa building their houses using techniques for bundling or weaving papyrus stems similar to that of the ancient Egyptians.

If he had known about them, he would have been further intrigued by swamp dwellers from other parts of the world, especially the Marsh Arabs, who live along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and build houses and mosques using bundles of reeds on floating islands in the same fashion as the Batwa. A major difference is that Marsh Arabs use the grass reed, phragmites, and their buildings are larger, sturdier, and more decorative than the Batwa’s papyrus huts, but the concept is the same.

In modern times, because of the war in Iraq, the lifestyle of the Marsh Arabs has changed and the area of the Iraqi marshes has been considerably reduced, but they still practice the same techniques of house and mosque construction with reeds as their forebears did thousands of years ago.

The count happened to be one of the few anthropologists of his day who had ever been inside a papyrus swamp, and the experience impressed him so greatly that a year after his visit to Egypt, he wrote a paper called “Did prehistoric Egyptian culture spring from a marsh-dwelling people?” His thesis was that one branch of the prehistoric culture of Egypt “germinated” from among a primitive people of hunters and fishermen who dwelt in the swamps of Lower Egypt. “Early Egyptian life was guided by swamp people. . . .”

As he wrote that, von Rosen could have had no idea that his theory of the origin of early ancient Egyptian life from swamp people, a culture represented by the world of the Batwa, would be dear to the hearts of many of today’s Afrocentrists, those who hold a view that emphasizes the importance of African people in the evolution of world history and civilization.

Though he never specifically says so, von Rosen’s paper suggests that he wouldn’t be at all surprised if someday someone found progenitors in Egypt who had come originally from Africa via papyrus rafts.

That there may be some basis for this theory comes from a story released in 2009 by a BBC news team. After examining the remains of Cleopatra’s sister Princess Arsinoe, found in Ephesus, Turkey, Hilke Thuer of the Austrian Academy of Sciences concluded that the evidence indicated that the mother of the two women had African facial features.1

The count was overwhelmed by the idea that ancient Egyptians, like the Batwa in modern times, made use of local materials to create a basic architecture that was carried forward into the annals of history. But in a way, it was just common sense. Papyrus played a large part in the construction of the early buildings in the Egyptian water-world because it was available everywhere, easy to work, and sacred.

Later, as settlements grew into towns, these archaic reed houses and rustic temples were replaced by mud-brick structures and stone constructions. The exceptions were in the small villages, where reed shrines probably persisted as the one and only choice.2

Archaic temple to Neith with a shield and arrow emblem of that god, built of light materials ca. 3000 B.C. (after Badawy).

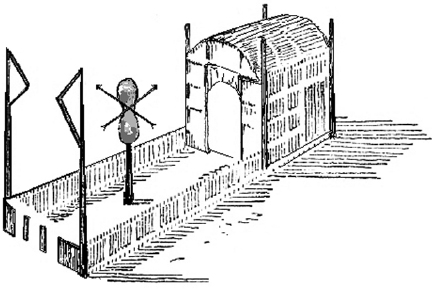

It is worthwhile to note that the temple builders of later times preserved the simple floor plan of the reed temple with a forecourt and main rectangular building, inside of which was the sanctuary. The two sacred flag-like structures at the entrance of the early reed temples were later replaced by pylons, often massive structures with flags on top, while the forecourts displayed elaborately painted masonry and spectacular columns that were incorporated into hypostyles, peristyles, etc. But the essence remained that of a reed or papyrus hut on a mound—an environment which from then on evoked the concept of the peace, quiet, and reverential space found inside a papyrus swamp. In these early buildings, bundles of reeds, a carryover from the days of the papyrus house, became a major feature, eventually morphing into the columns and open capitals of later years.

Outline of the floor plan of New Kingdom temples (1575–1085 B.C.).

In Egypt the temple was the cosmos in microcosm. Enclosed as it was by the outer walls and accompanied by a temple lake, it resembled the sacred primeval lake of Nun, the god of the waters of chaos and the father of Ra. The hypostyle hall in front of the sanctuary and its papyriform columns recalled a papyrus swamp not only because of their form but also because they were often provided in excess (that is, there were more columns than needed to support the roof).3

Further proof that these sophisticated temples emulated a natural setting were: the ceilings of the halls decorated to represent the sky; basal walls fashioned to represent the swamp that surrounded the whole; and the mound on which the sanctuary stood representing the place of First Creation. “Situated in sacred space and time, the temple was a divine domain on earth.”4

Reed temples built on mounds above high water had allowances made in order to have access to the river during the inundation. We see this feature in the later temples where an avenue was made, flanked by sphinxes, or a canal was dug to provide a connection to the water. It was assumed that the temple gods would need access to the river, as did everyone else, so a papyriform temple boat was provided. This was a boat fashioned after a papyrus skiff, or more often it was a replica of one that could be carried by the priests during festival processions as they transported sacred images to the water’s edge. In drier regions the boat or replica was even mounted on wheels.

The transition from reed or papyrus huts to some of the most impressive monuments ever built among temple architecture, and the role played by papyrus in this transition, is striking. In many ways, world architecture begins at Saqqara and Luxor, where the sacred towering plant was a major symbol and inspiration.

Traveling to Luxor, as with all sailing on the Nile, was at most times an easy task because little effort was involved either way. The prevailing wind is from the north, thus boats can sail upstream and then drift down with the river current on their return journey. Easy to remember when you think of the hieroglyph for the expression “travel up the river, or south” which is a papyriform boat with sail set. The same glyph with sail furled is used to mean “travel down the river, or north.”

On arrival at the modern town of Luxor, which is the southern part of what was once Thebes (the northern part on the river’s eastern bank is known as Karnak), we find many religious buildings that include some of the largest temples ever built. Especially interesting is the Temple of Amon-Re, which despite thousands of years of architectural evolution still has the familiar rectangular ground plan. Passing through the temple, we see papyrus reflected in the motifs and symbolic carvings, even in the pylons, of which there are no fewer than ten. These large rectangular towers with slightly sloping faces are separated by courts and halls, but along their edges we see an edge molding carved to represent bundles of reeds, a concept that takes us back once again to the original reed temple huts and their gated enclosures.

Similarly, the overhanging fringe, or cornice, that runs along the upper edge of the pylons is said to represent the drooping heads of the plants.

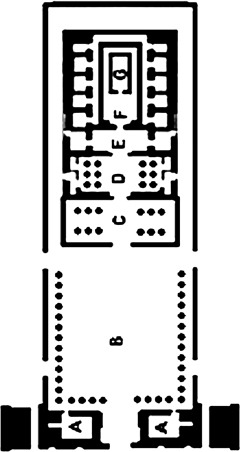

Once inside the temple compound, the most striking feature is the vast Hypostyle Hall commissioned by Seti I and finished by his son, Rameses II. Within an area of some 54,000 sq. ft. we find twelve enormous columns, some 80ft high, that once supported the roofing slabs of the central aisle to produce a clerestory. Today they are clearly seen as symbols of papyrus and are referred to as “papyriform,” with open capitals resembling the umbels of the sacred plant. At night the columns are illuminated, glorifying papyrus as never before. These columns are certainly large enough to make a lasting impression on even the most jaded of all ancient or modern tourists, and this fluted papyrus column form has influenced architecture throughout history, from classical Greek and Roman architecture even to the columns in the Washington, DC Metro system.

Progressing through this temple compound, we come upon one of the most common forms in Egyptian temple architecture: the bundled column. It resembles a bundle of reeds bound together to provide strength. These bundled columns in later years were refined and simplified, and appear again in a more streamlined form in the fluted columns of Greek and Roman times. Other plants were also models for columns and other structures in the Egyptian temples, especially the lotus, acanthus, and palm tree, but there is a primacy to the role of papyrus, in that the swamps dominated by this plant were the settings for some of the most important of the ancient religious legends of the Egyptians.

Tall, open papyriform column, 1400 B.C. Insert shows a bundled papyriform column, 2600 B.C.

Horus, falcon-headed god of all Egypt, patron lord of the kings and son of Osiris, King of the Blessed Dead, was born and lived his early life in the papyrus swamp at Chemmis in the Nile Delta. And Anubis, jackal-headed god of the dead, stood guard over the entrance to papyrus swamps at the northern part of the underworld, through which no soul could pass until judged. But above all else, papyrus played an elemental part in the lives of Osiris and Isis.

Osiris reigned as king of the earth and not without reason; he had civilized the archaic inhabitants of the Nile Valley by giving them laws, teaching them what to eat and how to grow and cultivate crops, as well as how to worship the gods. His jealous brother, Seth, killed him, then, blinded by rage, ripped him into fourteen pieces and scattered them throughout Egypt. For many years Osiris’s wife, the goddess Isis, sailed up and down the Nile swamps in a papyrus skiff, looking for the pieces; and that is why when people sail in boats made of papyrus, it is said that crocodiles do not hurt them for fear and respect of the goddess. And that is the reason, too, why there are so many graves of Osiris in Egypt, for she buried each limb or portion as she found it, where she found it.

In a larger sense, the swamps have an additional importance in that when the dead arrived at their final resting place, the followers of Osiris believed they would live forever in a celestial marsh similar to the papyrus swamps here on Earth.

Sekhet-Aanru, or Field of the Reeds, was a name originally given to the islands in the Delta, or to the Oases, where the souls of the dead were supposed to live. Here was the abode of the god Osiris, who bestowed estates in it upon those who had been his followers, and here the beatified dead led a new existence and regaled themselves upon food of every kind, which was given to them in abundance. According to . . . the Book of the Dead, the Sekhet-Aanru is the third division of the Sekhet-hetepu, or “Fields of Peace,” which have been compared with the Elysian Fields of the Greeks. (E. A. Wallis Budge, The Book of the Dead, 1895)

The temples then were representations of the sacred papyrus swamps, houses of the immortals, and also the universe at the moment of creation; above all, they were timeless havens under the protection of the spreading umbels. Like the mounds first built by Egyptians to provide escape from the inundation of the river, the temples became in the Egyptian mind a mound of survival, and each day at dawn the doors of the sanctuary were opened by the priests, and the world was recreated as they brought forth a new day out of the waters of chaos. It was the focus of cosmic order, “the radiant place.”

Standing inside the Amun-Re Temple is akin to standing in any other large columned space. You could as well be in one of the large cathedrals of the west or the major temples of the east. What sound there is diminishes quickly from an echo to a whispering sound as the tourist crowd passes through and the space takes over your mind. Deep into a natural swamp the only noise will be the umbels above you waving gently as a breeze passes overhead. That creates the whispering, soft sighing that is as unworldly as any sound in nature, but very much like the sound that you hear inside the temple in Luxor.

Von Rosen, unusual in that he could appreciate what it meant to be a swamp dweller, was amazed at the fact that so few scholars before him had commented on the importance of papyrus swamps to the ancient Egyptians. His enchantment with the notion of the swamp as a place to live joined him philosophically with another radical, the 19th-century thinker and naturalist Henry Thoreau.

Dr. Rod Giblett, a writer, lecturer, and conservationist at the Edith Cowan University in Australia, called Thoreau the “Patron Saint of Swamps” because he enjoyed being in them and writing about them. For Thoreau, “my temple is the swamp. . . . When I would recreate myself, I seek the darkest wood, the thickest and most impenetrable and to the citizen, most dismal, swamp. I enter a swamp as a sacred place, a sanctum sanctorum . . . I seemed to have reached a new world, so wild a place . . . far away from human society. What’s the need of visiting far-off mountains and bogs, if a half-hour’s walk will carry me into such wildness and novelty.”5

Who would have thought a New England Yankee could have put the case so well? This sums up not only Count von Rosen’s feelings—but that of the ancient Egyptians.

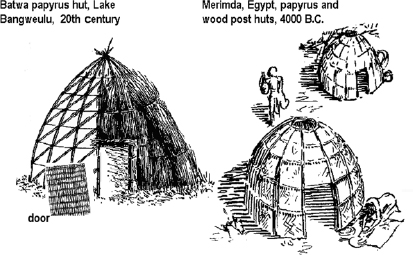

No permanent housing structures have survived from pre-pharaonic times in Egypt, but some evidence exists suggesting that, in addition to mud-brick buildings, reed huts were also in use in the Faiyum and Merimda region. Postholes dated ca. 4700 B.C. suggest that if such structures existed, they were oval in shape with poles overlain with mats or reeds.6 In the early days, also, small reed houses and reed temples built on mounds probably came to be as much of what Lewis calls “the Egyptian style of architecture” as the monumental constructions of pharaohs and cities of innumerable mud-brick buildings. Badawy’s reconstruction of these ancient huts looked a great deal like those of the Batwa.

Batwa papyrus hut under construction compared to ancient Egyptian papyrus huts (after von Rosen and Badawy).

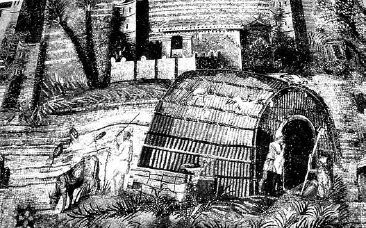

One view of what an early Egyptian papyrus hut on a floating mat might look like is shown in a famous mosaic that dates from 100 B.C. A vestige of Sulla’s sanctuary in Palestrina, Italy—a sacred place dedicated to Fortune that was at the time the largest sanctuary in Italy—the mosaic depicts the inundation of the Nile in Roman times. It may have no basis in fact, since it was fashioned from the impressions of ancient travelers, but the house in the mosaic looks very much like the houses of the Marsh Arabs. This leaves open a number of interesting possibilities, especially when we look at ancient reed structures that were reconstructed by the architect Badawy from very old clay tablets, seals, implements, and temple drawings.

A reed house in ancient Egypt during inundation in Roman times (Palestrina mosaic, Italy).

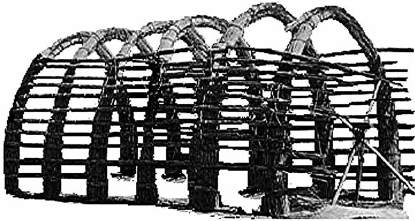

Some of his drawings are uncanny in their resemblance to the reed houses and mosques of the modern-day Marsh Arabs in Iraq. Their distinctive type of construction is still in use after 3,000 years, though it may be older still, as the same communal buildings seen in contemporary marsh culture were found on Sumerian seals from 5,000 years ago. The anthropologist Paula Nielson points out that the agricultural and irrigation practices were similar between the ancient Sumerians and the Marsh Arab. Like Marsh Arabs still do today, the Sumerians traveled in slender reed boats, caught fish and birds with long spears, lived on marsh islands in reed houses, and herded water buffalo, sheep, and cattle.7

The type of construction used involves the bundling and binding of reeds to form “posts.” The butt ends of these posts are sunk into the substratum, where they can then be left upright to support a standing wall or bent over to be interwoven and joined with opposing members to form an arch. Once covered with reed mats, the result is an astonishingly strong vaulted building similar to a Quonset hut. This kind of house is much more versatile than mud brick, as it can be built on dry land or inside a marsh or swamp or on a mound of reeds. In Iraq today, the whole mound on which the houses are built rises and falls with local water levels. It is doubtful that the whole mass of a papyrus swamp would so react, as it is much too heavy to easily raise or lower with sudden changes in water level. A more fascinating possibility is that suggested by Badawy, that huts woven from papyrus were simply mounted directly on boats, which would be very light in comparison to the whole swamp. In the early days, he says, “It may be surmised that settlers on both sides of the Nile erected their shelters and huts in the style of the (boat) cabins. . . .”

Building a Marsh Arab house (after Ochsenschlager).

Herodotus is silent about any housing used by these people; we have to assume that if they were using a particularly distinctive type of housing by then (440 B.C.), we would have heard about it or seen traces in paintings or reliefs. If the ancient Egyptian marsh men did build houses inside papyrus swamps, they would have had an advantage over the Marsh Arab since, as Thor Heyerdahl found, the Marsh Arabs’ floating mounds on which they build their houses—simple platforms made of reeds laid down over many years—are soft, almost unsteady. In a papyrus swamp the interlocking matrix of the rhizomes, though it also undulates, provides a much stronger foundation than that of the floating reed islands in Iraq.

Without papyrus, hundreds of thousands of settlers in prehistoric and pre-dynastic Egypt would have had to survive the inundation with houses built of alternate materials, a process that would require thousands of years to evolve. Such housing would also have to wait until mounds were built above the flood. All indications are that, as with boats on the early Nile, a shortage of housing during the period 7000 B.C. to 3500 B.C. would mean a slower rate of development, less production, and a slower advance of civilization. A world without papyrus could only have been seen as a great setback.

In addition to the habitations of marsh men in ancient Egypt, it is also interesting to speculate on what the Egyptian terrain would have looked like during inundation. Herodotus tells us that, in the time of the first human king of Egypt, “. . . all of Egypt except the Thebaic district was a marsh: all the country that we now see was then covered by water, north of Lake Moeris, which is seven days’ journey up the river from the sea. . . . And I think that their account of the country was true. For even if a man has not heard it before, he can readily see, if he has sense, that that Egypt to which the Greeks sail is land deposited for the Egyptians, the river’s gift—not only the lower country, but even the land as far as three days’ voyage above the lake. . . . Inland from the sea as far as Heliopolis, Egypt is a wide land, all flat and watery and marshy.”

The agricultural year did not begin until the inundation subsided in autumn, leaving the earth of the floodplain soaked and overlaid with a fresh layer of black silt. The impression one gets is that the floodplain was emptied of vegetation, domestic animals, and people during the floods of summer and early autumn.

“When the Nile overflows the land, only the towns are seen high and dry above the water, very like the islands in the Aegean sea. These alone stand out, the rest of Egypt being a sheet of water. . . .”

In later times, mud-brick houses predominated in and around Egyptian cities and towns, and also in agricultural settlements on dry land; but a substantial number of people, fishermen, boat builders, papermakers, craftsmen, and their families still lived closer to their work in or near swamps. The Floating World in ancient Egypt thus provided an opportunity for early architects and craftspeople to create what Prof. Badawy called “prototypes,” compact bundles of papyrus reeds that served as corner posts and arch supports. First made by simply tying dried papyrus stems together with rope and twine (also made from papyrus), the bundles could then be shaped and fashioned into all sorts of designs. These were the forerunners of the fluted columns and scalloped parapets, as well as vaults and domes that were later copied in brick and stone to become the architecture of the Western world.