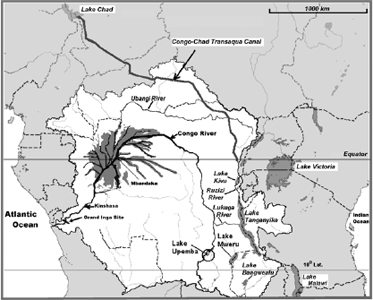

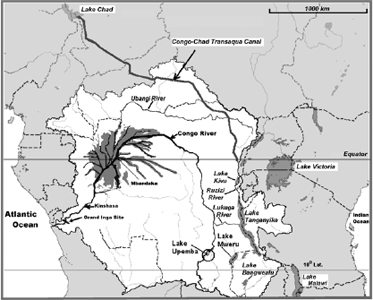

MAP 5: The Congo River catchment, central wetlands, and sites of the Grand Inga Dam and Transaqua Canal.

The Congo, Economic Miracle or Pit of Despair

The migration of millions of birds in the winter was one of the most well-kept secrets of nature until the 20th century. Prior to that, according to Frederick Lincoln, the pioneer bird bander who spent 26 years banding birds with the Department of the Interior, people thought birds simply went into a torpid state and hid in hollow trees or burrowed into marsh mud for half of the year. This despite the clue offered by the Bible in the Book of Job (39:26), where we find a leading question that gives it all away: “Doth the hawk fly by Thy wisdom and stretch her wings toward the south?”

Still, the answer to the puzzle had to wait until another, more vivid clue was dropped, one worthy of Agatha Christie—the appearance of several storks in Germany with African arrows embedded in them. The oldest of these Pfeilstorche (German for “arrow stork”) was a white stork shot on an estate near Mecklenburg in 1822 that had its neck pierced with a 32-inch African arrow. More were to follow. To date, around 25 have been documented.

African arrows are distinctive. I have one that I bought off a tribesman in Botswana. I was tempted to bargain for it until he told me that it still had dried poison on it. At that point I knew I had to have it at all costs. It is made from a dark, tough, springy wood carved and polished and fitted with a razor-sharp metal point. It has a cluster of five feather fletches on the notched end and looks positively deadly.

How a bird pierced with such a thing would have survived is a wonder, especially one that had to fly thousands of miles back to Europe with it hanging from its neck, but the plight of the Pfeilstorche was not in vain. By 1900, migratory patterns had been worked out showing that some birds, like the Eurasian crane, and the white stork that we followed earlier, come to Africa along the eastern flyway, which takes them to the Jordan Valley, then south toward Lake Victoria. Other birds, like the great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus), head southwest coming from Europe and fly on a direct line overland to the Congo region, where they join a large resident population that lives in the wetlands there.

Flying as they do on thermals at great altitudes (9–12,000ft), their view of the Congo River would be much like that of most people who see the river on a map for the first time (Map 5, p. 141). That long, lazy loop, the classic “bend in the river,” jumps out at you as it cuts right across the middle of the continent and passes through the heart of the land mass.

“An immense snake uncoiled,” thought Conrad’s narrator, Marlow, looking at a map of it in the window of a bookshop, “its head in the sea . . . and its tail lost in the depths of the land. . . .” He went along Fleet Street but could not shake off the idea; “the snake had charmed him.”1

A closer look at the same river on a detailed topographic map reveals myriad tributaries, thousands of them bending toward the main stream. As impressive as maps are, the enormity of the Congo River doesn’t come home until you fly over it in a light plane. From the same height as our great white pelican you will see one of the last untamed rivers, with a torrent of water in its lower section that widens into a broad moving sheet ranging in width from 0.5 to 10 miles.

MAP 5: The Congo River catchment, central wetlands, and sites of the Grand Inga Dam and Transaqua Canal.

The Congo has recently been found to be the deepest river in the world—750ft in some places. The Mississippi is 200ft deep at its deepest point, while the Nile averages only 33ft. Constantly moving, the Congo swells in May and December, but still flows during all seasons because the basin is so large that there is rain falling someplace within the system every day of the year. An annual rainfall of 6–8ft in the basin results in over one million cubic feet of water that flows into the South Atlantic every second.

Another unusual feature of the river is the constant parade of plant material that travels downstream. Whole trees, logs, huge rafts of floating aquatic weeds, water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), and water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes) and other plant matter goes drifting by unhindered. On the lower Nile, or on the Zambezi, there is no similar parade because both are well dammed. Watching from the banks of the Congo, the most conspicuous plant in the flotsam is papyrus. Small clumps as well as immense islands weighing several tons pass by. The stems in every case are topped by umbels that stand out and identify this unique plant that generates a constant stream of floating biomass.

Below Kinshasa, before it reaches the sea the river passes through a constriction, a series of rapids and cataracts that will tear apart and break up any large mass of plant matter. The floating bits that survive are washed out of the mouth onto the beaches along the north coast.

Walking along that strand one sunny day, I was amazed to see thousands of old papyrus rhizomes drying in windrows in the sun.

Offshore I could see a few islands of papyrus floating out to sea. Papyrus is sensitive to salinity and wouldn’t survive in the ocean, but tons of riverine vegetation must be discharged from the river every day. So much papyrus passes down the main stream that Dr. Melanie Stiassny, an ichthyologist and curator with the American Museum of Natural History in New York and leader of a recent fish-collecting expedition on the Congo, was prompted to ask me, “Where is it all coming from?”

The answer is easy if you fly upstream along the river. Along the way you pass over an amazing vista of swamp forests, marshes, and swamps, among which papyrus is easily distinguished. It grows along the edges of bays or places in the floodplain wherever water is slow-moving. From the air the form of the plant makes an impression, as it appears to be an even carpet of light green that covers the valleys and smaller bodies of standing water.

As you go further south, deeper into the basin, along the shores of Lakes Upemba and Bangweulu you come to the source of the Congo, where papyrus grows unhindered among the lakes, ponds, and riverbanks, and in the valleys of the tributaries. It is here that the headwaters of the Nile, Congo, and Zambezi come close to meeting. This watery region constitutes only a small part of the 1.4 million square mile catchment of the river, but within the Congo Basin, during times of drought, it is vital. Papyrus swamps are so plentiful in this region that it is hard to escape the conclusion that the swamps are the long-sought Holy Grail of the Victorian explorers: the cradle of African waters.

In the 1960s, during the early days of African independence, the key word in swamp preservation was “isolation.” The low density of people in the Central Congo Basin, and the large expanses of flooded terrain, meant that there would be few people to even begin clearing these areas; and if they did begin clearing, the effects would be insignificant.

Things change. Civil disturbance in Africa drives local people into desperate circumstances, forcing them to become refugees. Rebel troops, the mai-mai, roaming the borders of the Congo rape, kill, and plunder. In an effort to escape, the refugees seek out national parks where game is available for food. Beyond the havoc caused among humans, rebels equipped with automatic weapons also slaughter game to feed their troops or else sell the carcasses on the black market, and in doing so further disrupt any effort at conservation.

To the east of the Congo, in Rwanda, on the Kagera River and in the Akagera National Park, land was taken over by refugees who had been driven out of Tanzania. They flocked there because the land was unoccupied, they were hungry, and they needed soil to raise crops to survive. This park contained some of the few untouched papyrus swamps left in Rwanda, preserved until then by isolation and park supervision. Today, much of the savanna region within the park is settled by the refugees, and at a national level the government has begun the process of repairing damage done by civil disturbance. The papyrus swamps survived; though the armed struggle is not over, the mai-mai have shifted operations to the eastern Congo region where they are still operating to this day.

It comes as a grim surprise to hear that in order to get away from the mai-mai, 8,000 refugees—mostly young people—voluntarily moved onto papyrus islands in Lake Upemba in the upper reaches of the river (Map 5, p. 141). According to a report by NPR journalist Jason Beaubien on All Things Considered (Feb. 2006), they felt safer on the islands despite the difficult conditions there. “The islands are almost like swamps,” Beaubien said, “the ground sinks under your feet.” This is similar to the papyrus swamp hiding places seen by Dr. Livingstone on the Shiré River and is physically not far from the Lake Bangweulu swamps of the Batwa who were visited by Count von Rosen.

On Lake Upemba, the largest concern of the relief agency Doctors Without Borders (Médecins sans Frontières) is that the swampy conditions are ideal for water-borne diseases. Outbreaks of cholera and malaria are rampant and made worse by the rains, which fall from October through May.

The only good news is that small gardens can be fashioned on the islands by importing soil and heaping it into mounds to grow onions, tomatoes, and squash. But manioc, their staple food, cannot be grown here; instead, they have fish, which are plentiful, and they have papyrus, ndago mwitu, the “people’s sedge,” which is one of the dominant plants in the Upemba wetlands. And the people who live there know that in an emergency the base of the green stems can be chewed like sugarcane and the rhizomes can be baked. Also it is useful to know, as did the ancient Egyptians, that the stems of papyrus can be used for thatching and weaving mats, baskets, and other household products. And the dry stems, once spread out, act as a substrate to walk on as well as providing floors inside papyrus huts. Dry stems also provide kindling to ignite dry rhizomes, which can be used as a wood-like fuel.

Many of the refugees will presumably move back to their villages if peaceful conditions ever come about, but that may not be for some time. In an interview with Beaubien, I was told that during the past ten years more people have lost their lives in this region than in all of World War II. Over four million have died so far, and a quick end to hostilities is not in sight. The swamps turn out to be useful in emergencies, but it’s best to look elsewhere for a place to live—unless one is of a rare breed like Mr. Onyango on Lake Kyoga and makes the floating papyrus swamp his permanent home.

Regardless of what one’s Cajun friends may say about living in a swamp, it is not something that people should undertake lightly. The largest problem is the mosquito. Though not common deep inside natural papyrus swamps, where abundant wildlife prevents eggs from ever hatching in the swamp waters, mosquitoes are devastating along the edges of papyrus swamps. The early inhabitants of the swamps in Egypt used oil from castor beans (Ricinus communis L, called kiki, according to Herodotus) to ward off the abundant flies and mosquitoes. “They sow this plant . . . on the banks of the rivers and lakes . . . it produces abundant fruit, though malodorous; when they gather this, some bruise and press it, others boil after roasting it, and collect the liquid that comes from it. This is thick and useful as oil for lamps, and gives off a strong smell.” In India years ago, castor oil was said to be among the best of the lamp oils, giving a white light far superior to most others. It is used in modern herbal insect repellents, such as that produced by Burt’s Bees, which also contains just about every essential oil known to man. Caution must be exerted, especially around food, since some people are very allergic to the castor plant and its products.

It happens, then, that in refugee camps or huts on the edges of papyrus swamps malaria is the number one cause of death. And it is a secret killer, because although adults suffer from infection, the population at first seems hardly affected, since infants and young children are the first to succumb and so the toll is not easily seen. In her book Lake Chad, Sylvia Sikes tells us that many of the Yedina who used to live in the papyrus swamps on Lake Chad used bed nets, but still infant mortality was high, so high that an infant was not named, nor its sex disclosed, for several days—a custom that insulated the mother from repeated disappointment and disgrace.

In Africa, the largest danger to marsh and swamp dwellers is the anopheles mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, one of the most common transmitters of the dangerous form of malaria, Plasmodium falciparum. Fortunately, many cures and preventatives exist today so that one need not die of malaria. The only problem is one of cost.

Fiammetta Rocco’s fascinating book Quinine tells the story of the natural drug that was first used to treat and prevent malaria and how it was obtained from the bark of cinchona, the “fever tree” found in the jungles of Peru: “The tree that was as crucial to the art of medicine as gunpowder had been to the art of war.”

She also makes the point that, after many years of development of synthetic alternatives, there is still a great need for quinine in Africa, since new formulations, though cheap in local drugstores in the West, are priced out of the reach of rural Africans. This leaves quinine, because it can be manufactured and distributed locally, as the most cost-effective treatment.

Cinchona ledgeriana, from which it is produced, is grown in Africa in the eastern Congo, and the bark is processed in the town of Bukavu by the company Pharmakina. Pharmakina persisted in growing and producing quinine in the face of the Rwanda-Congo war, which was in itself something of a miracle. How the company survived is a story told by Rocco that reads like a scene out of the movie Hotel Rwanda. Whereas thousands were affected by the intercession of Paul Rusesabagina in his well-known hotel in Kigali, Pharmakina saved the lives of millions. This is because so many in Africa are dependent on the production of the company, which is still very much in business and active in the development of the region.

Quinine interferes with the parasite’s ability to break down and digest hemoglobin. It literally starves the parasite. Of interest are the discoveries of several other natural compounds, including Artemisinin, which is extracted from a common weed, wormwood, Artemisia annua. Native to temperate Asia and naturalized throughout the world, it has been known for 2,000 years for its curative effects on fever, hemorrhoids, and skin diseases. The latest research has shown that it also has strong effects on malaria. The active ingredient Artemisinin effectively treats malaria in human subjects with no apparent adverse reactions or side effects.

Another natural drug, Tazopsine, comes from a tropical forest tree that grows in Madagascar. Unlike quinine, which acts at the level of the blood, Tazopsine is active at the early stage of infection in the liver, and therefore may lead to a cheap effective malaria prophylactic—a godsend to those at risk.

In places where malaria is prevalent, it is possible to develop a limited immunity to the disease. This does not prevent one from developing malaria again, but does protect against the most serious effects. One could develop a mild form of the disease that does not last very long and is unlikely to be fatal. Early in my career in Africa, I came down with a mild dose that persuaded me to take chloroquine on a regular basis, as I would be spending so much of my time in the swamps. After a while I came to realize that I was, paradoxically, in more danger outside the swamp than inside, where there were few mosquitoes. The malarial carrier Anopheles gambiae doesn’t breed in the interior of papyrus swamps because the mosquito larvae are preyed on by dragonfly larvae and predacious water beetles (Dytiscidae).2 Mostly the larvae breed on the periphery, in hoofprints at cattle drinking places and other disturbed areas or in open natural pools. Rocco’s book describes her family’s battle with the disease during the years when she was growing up on the shores of Lake Naivasha, along the edges of papyrus swamps where the most dangerous places are.

Anti-malarial programs during the years just after World War II included aerial spraying of papyrus swamps as a precaution against the disease. Now the experts say that the spraying of the swamps was a waste of time and money, and may even have made it worse because the chemicals that kill the mosquito larvae are the same that kill off the natural predators of the mosquito, such as beetle and dragonfly larvae. It is best then to limit the spraying to the swamp margins, where the incidence is highest. Humans who move into the edges of papyrus swamps do so because they are attracted by the safety that the swamps provide, but within a short period of time they realize that in many ways, it is its own sort of death trap.