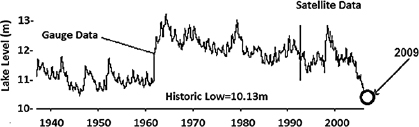

Water levels in Lake Victoria were unusually high from the mid-1960s until December 2005. Since then, water levels have dropped significantly (Simmon and USDA).

The Papyrus Yellow Warbler (Chloropeta gracilirostris), White-winged Warbler (Bradypterus carpalis), Carruthers’s Cisticola (Cisticola carruthersi), Papyrus Gonolek (Laniarius mufumbiri) and Papyrus Canary (Serinus koliensis) are all five confined to swamps in the western arm of the Rift Valley and around Lake Victoria, spending most, if not all of their time in papyrus swamps.

—A. Owino and P. Ryan, 2006,

African Jour. of Ecology

One day while waiting at JFK airport in New York for an onward connection, I turned to the best seller Passages, by Gail Sheehy, to while away a few hours. This was the original narrative about predictable crises in life. Not usually my kind of book, but I was at a stage where I had to make decisions about my career, and someone had told me to read Sheehy’s book: “It might help.”

In a way, it did, as it reminded me of how many phenomena in nature are geared to cycles. Even the “seven-year itch” in marriages could be due to external forces, much like the effect that sunspots have on the weather. This was an idea that definitely rang a bell. I’d always been curious about the extremes that are so obvious in Africa, where once a drought sets in it lasts for about five or more years; then comes rain unlike anything you can imagine, causing floods that set everything awash for another half dozen years. It’s truly feast or famine, and it takes about eleven years for these cycles to complete themselves.

This is the basis for the theory that the weather in Africa and elsewhere is correlated with sunspot eruptions, which happen about every eleven years. The first indication is an increase in magnetic activity in the atmosphere, followed by rain, then a rise in lake levels. The theory has still to be proved, and any mechanism behind it, if it does exist, is still uncertain,1 but recent research found that all nine of the past century’s sunspot maxima coincided with maximum water levels in Lake Victoria.2 When I began writing this book, the next peak in the sunspot cycle was predicted for 2011, when heavy rains were expected to pummel East Africa—which they did. Prior to that time, drought had set in and lakes had been drying up. Lake Chad, the papyrus-fringed lake in the arid zone of North Africa, had shrunken until it was only a shadow of its former self. The Kenyan lake, Lake Naivasha, followed suit. Also of note was the decrease in Lake Victoria. At 26,563 square miles, it is the largest freshwater lake in Africa. In 2006 it dropped by over seven feet, reaching its lowest level in eighty years!

Where was the water going? The only way in which such an enormous drop in level could happen would be if water were lost through the Victoria Nile at Jinja, which is the only exit for the lake. But when asked about such things, the authorities in Uganda who control the flow through the dam at Jinja turned a deaf ear. Even as the Ugandan weekly, Sunday Vision, reported that the water level at Entebbe had dropped by over 3ft and the shoreline had retreated by more than 120ft, the Uganda Electricity Board in 2006 continued to blame the loss on drought, global warming, and excessive evaporation from the lake itself.

“Until it stops I don’t know how we could stop the water levels from falling,” said Dr. Frank Sebbowa of the Uganda Electricity Regulation Authority.

Water levels in Lake Victoria were unusually high from the mid-1960s until December 2005. Since then, water levels have dropped significantly (Simmon and USDA).

The East Africa Business Week (January 2006) disagreed. They accused the water authority board in Uganda of simply disregarding the rules and spilling water through the Nalubaale Dam, the only exit from the lake. This is a hydroelectric facility located at a place formerly called Owens Falls. Nalubaale, together with the smaller Kiira station downstream, is operated by a private firm that is supposed to release water in accordance with what is known as the “Agreed Curve.” The Agreed Curve is the adopted policy ensuring that the water released through the dam corresponds to the natural flow of the Nile River. It was adopted by the British and Egyptian governments to ensure that the water released from Lake Victoria for downstream users is released at a rate based on the flow before the dam was constructed in 1954. In this way, Egypt would be guaranteed a water supply while the lake level would be maintained at some reasonable level.

In June 2006 Daniel Kull, a hydrologist with the UN’s International Strategy for Disaster Reduction in Nairobi, in an online newsletter dealing with current water issues, reported that it was clear that “The Agreed Curve is no longer being adhered to, and the resultant over-release of water from Nalubaale and Kiira is contributing to the severe drop in water level in Lake Victoria.”

By now, papyrus swamps on the edge of the lake had begun to dry out. Since 30 million people, one way or another, depend on the lake for water, concern was soon voiced and photos appeared in the local press showing lakeside villages high and dry and fishermen with boats abandoned in the middle of mud flats far from the water’s edge. It was clear that the reason the lake was drying was the fact that Uganda was ignoring its responsibility of maintaining the natural lake balance. The result was a great deal of ill feeling in a country with years of hostility from Amin’s reign of terror still bubbling beneath the surface.

Since the lake is a shared resource, and Kenya and Tanzania intend to use the waters for their own development projects, it came as a shock to discover that from now on the level would simply go down, inexorably dropping every year. While resource managers in Tanzania and Kenya were being bombarded by questions from fishermen and tour companies, the media were firing off a continuous round of crisis messages about the death of the lake along with headlines blasting Uganda for stealing the livelihoods of thousands. Worse, politicians in Tanzania and Kenya found there was nothing they could do about it. As lakeside residents in all three countries stood by and watched the level drop, no explanations, no excuses were forthcoming, though activists even in Uganda were not slow in pointing the finger. “This dam complex is pulling the plug on Lake Victoria,” said Frank Muramuzi of Uganda’s National Association of Professional Environmentalists.

As the crisis deepened, the message came home to the world that papyrus swamps made up an important part of the wetlands that surround the lake. An estimated 2,300 square miles (1.5 million acres) of papyrus swamps (about half the total of 4,000 square miles of wetlands in the basin3) extend along the lake shore and up local rivers into nearby valleys. Because environmental education is now well established in East African schools, and the general public is nature-conscious, there was never any argument locally about the value of swamps to conservation. On the Ugandan side, two papyrus swamps have even been designated Ramsar sites. Ramsar sites (named after the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty) are internationally recognized wetlands. One site, the Mabamba Bay Wetland System, is located along the lake shore west of Entebbe International Airport (5,990 acres) and the other, the Lutembe Bay Wetland System, a shallow swamp area (242 acres), is at the mouth of Lake Victoria’s Murchison Bay.

Conservation of these swamps has become critical because of new evidence regarding the ability of papyrus to act as a nutrient “sieve” and a physical barrier to sediment. The concept is based on the use of vegetation to filter effluents as a step in naturally purifying outflows from sewage plants. Known as water “polishing” by water engineers, it is a widely accepted technique, similar to the concept of filter marshes used in the Everglades.

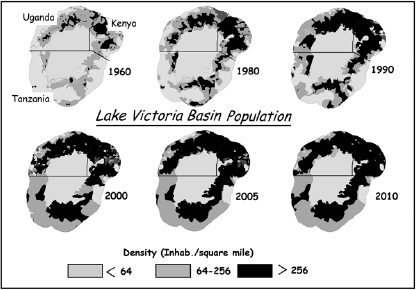

In the Lake Victoria region, urbanization is going forward in a big way and towns along the shore have experienced significant growth in urban population. It is predicted that the growth rate around the lake will not let up, which means that more and more people in the future will depend on the lake’s water level being held close to normal.

Population density in the lake region (UNEP/GRID).

Not only is this necessary in order to provide access to fisheries and tourism, but there is a need to provide dilution of the many forms of pollution from runoff and urban sewage that go directly into the lake. Even in urban centers such as Entebbe, Kampala, Mwanza, and Kisumu, the swamps are the only backup when municipal sewage systems cease working because of power outages, flooding, or overloading, which happen frequently.

Under such conditions, the benefits from the filtration by papyrus swamps—and their protection from drying out due to dropping water levels—could be the most significant thing happening to the lake over the next decade.

Filter Swamps—Harvesting and Management

The role of papyrus in filtering sewage is illustrated by the work of several teams studying the effect of wastewater discharge on local flora. Papyrus was selected as one of several plants studied because it is considered to form one of the most productive plant communities on earth, no mean feat considering the millions of plants that exist on this planet. The studies were also of interest to me because Nakivubu Swamp in Kampala was included.4 This is the same swamp I visited on my arrival in Uganda in the early ’70s, and it is the same swamp where I noticed the sewage canal and the smell. The outflow from the Kampala city municipal sewage-treatment plant is passed by way of this canal into the swamp. From there it flows on into the lake. At present this amounts to an input of five million gallons per day of highly nitrogenous wastewater.

The team found that the plants in the papyrus swamps through which the sewage passes react as would any plant to nutrient-rich fertilizer: they grew bigger and heavier. They also took up more than the average nitrogen and phosphorus and retained higher levels of these nutrients in their tissues. All of which indicates that papyrus swamps would act as a filter.

In much of inland Africa, natural wetlands act as physical catchments to trap mud and silt, but it is their ability to act as filters to control pollution and especially to release nitrogen as gas to the atmosphere (“denitrify”) that encourages people to use wetlands in the first place. As much as 1.32 tons of nitrate-nitrogen can be denitrified for every acre of wetland each year.5 This is an amazing level of no-cost water treatment.

The removal of phosphorus by the same wetlands is more difficult. Some phosphorus is combined with iron, aluminum, and calcium compounds. It is in this way sequestered and trapped in the microbial layer surrounding the roots (the “biofilm”) as well as in the oxygen-poor peat, silt, and mud.

A small amount of phosphorus is also taken up directly into the stems and rhizomes of the plants and other living organisms in the wetland ecosystem, where it is used for growth. But as a rough guide in planning, the more total phosphorus that needs to be removed from the wastewater, the larger the vegetative component will need to be.

As mentioned before, natural wetland filters can be made more effective if they are harvested. This is equivalent to changing the paper or cartridge in any sort of filter. Harvesting in this case means cutting and removing, not just burning, because burning the stems within the swamp would just speed up the recycling. The best-case scenario is for the cut stems to be removed to a place on land some distance from the lake, where they can then be mulched or safely burned to provide ash as a fertilizer for cultivated plots. Another option is to chop them up and incorporate them in building material or pelleted fuel.

But even if a wetland is not harvested, it still does a good job since the older parts of the plant deposited as peat and the biofilm that sloughs off can lock in enormous amounts of nutrients over the years.

All of this is true of man-made filter swamps as well. Some constructed wetlands, for example, have operated as N and P filters for over 20 years before having to be renewed.6

Filter Swamps—Gone but Not Forgotten

During the recent well-publicized drought on the lake from 2000 to 2009 that left the papyrus swamps high and dry, the fear persisted that come 2011, at the end of the 11-year long-range weather cycle, when the rains finally did come there would be a great erosional flush of nutrients off the land directly into the lake. Nutrients would also be released from the dead swamp vegetation, and that would be washed in along with sewage—all of which happened.

The sad thing is that it could have been prevented by a more rigorous energy and water conservation effort along with a lake-wide action plan carried out in a truly multilateral way. As a result of this neglect, today the lake is considered “eutrophic,” the polite word that means “over-rich in nutrients,” or polluted.

One effect of such enrichment is the upsurge in growth of algae, or “blooms,” which results in an excess of organic matter and a strong depletion of oxygen in the water (which was discussed earlier). This is the same effect seen in a fish tank when a fish hobbyist overloads the tank with fish food. The fish die of suffocation in the tank as in nature. In Lake Victoria, the flush from the land in 2011 produced an increase in algae and aquatic weeds (water hyacinth), which thrived on the new nutrient inflow. This is the same effect seen in the Sea of Galilee when the Huleh Swamps were cleared years ago, but now it is a change that can be followed from space. Thus, several years ago during a period of unusually heavy rains, the influx of runoff and nutrient-rich sediment into Lake Victoria was spotted by a NASA satellite equipped with an MRI spectroradiometer.7 The satellite detected a change in color of the water in one bay of the lake, which changed initially from its normal blue to brown, followed by a dramatic increase in green from algae and water weeds. The NASA report was interpreted as a flush of nutrients that was confirmed on the ground by a fresh outbreak of water hyacinth and algae.

Over the last five years a general decline in fisheries on the lake by more than 50% has been ascribed to overfishing, but after the rains in 2011, reports appeared in newspapers, on TV and radio of a further decrease in fishing due to a large increase in the growth of water weeds.8 This comes as bad news for the 60,000 fishermen who depend on the lake for their livelihoods. The problem is made worse because the water in this lake is also a major drinking water supply for millions of people. In 2004, algal blooms on the eastern (Kenyan) side of the lake resulted in a temporary shutdown of the drinking water supply to Kisumu, a town of one million inhabitants.9

Until proper sewage treatment is installed lake-wide on Lake Victoria, the low-cost solution to this massive problem is to encourage the growth and well-being of papyrus swamps. This can be done by maintaining high water levels and harvesting papyrus stems and water weeds for use as soil amendments and green fertilizer at a distance from the lake. This will also help curb the algal blooms and bring nutrient levels down. It has been estimated that if the wastewater entering Lake Victoria was more equitably distributed over a larger portion of the swamps, and harvesting and removal were carried out, up to 70% of the nitrogen and 76% of the phosphorus coming into the lake from effluents could be removed.10

Tourism and Multiuse—a Lesson from the Ancient Egyptians

Despite their positive role as virtually cost-free filters, the papyrus swamps of the lake are not well conserved. A recent aerial photographic survey along the shores of Lake Victoria by Owino and Ryan showed losses in the swamp cover in some areas of 34–50% between 1969 and 2000. This is due to the attractiveness of swampland to farmers. Because of its rich organic content and its closeness to water, the land is often deemed available for farming and settlement whether or not it is protected by law. Once cleared of papyrus, the land is immediately put under cultivation by farmers who know how to deal with peat, and they put it to good use. However, they could also be conservation-minded by helping to replant a certain portion of the lakeside in papyrus once the water again rises, but this doesn’t happen and the loss continues.

Owino and Ryan predicted that at the current rate of loss, the swamps immediately bordering Lake Victoria will disappear by 2020. In that case, people in East Africa will begin suffering from the same fate Egyptians suffer today. What’s the solution? One way to conserve the swamps is to manage them as part of a multiuse program. In that way, users become stakeholders and manage them much like the owners of papyrus plantations did in ancient times in Egypt.

Ilya Maclean of the University of Exeter in England, with a team of colleagues from the University of East Anglia, carried out an in-depth study of the value of papyrus swamps in East Africa in the region around the lake. Using satellite imagery and fieldwork, they looked at over 30,000 small and large papyrus swamps in Uganda alone. Maclean concluded that the most profitable solution to swamp conservation in the region, and probably many other places in Africa, lay in the traditional multiuse system already practiced by many rural households in Uganda.

This involves the harvest of papyrus stems for thatching, wall and ceiling screens, fences and floor mats, and for making handicrafts such as baskets, hats, fish traps, winnowing trays, and table mats. The multiuse of a neighborhood swamp is not restricted to crafts, but includes clearing small patches for subsistence farming, small-scale brickmaking, and fishing in and near the swamp. Maclean’s work provides further guidelines. He calculated that the average household could harvest about 1,500 papyrus culms per year from local swamps, and as long as the density of people did not exceed one to two households per acre, the swamp would survive.

He also found that the average direct return would usually be in excess of $4,200 per acre of swamp, which is enough to support a Ugandan household on a sustainable basis (where the per capita income in 2003 averaged $1,440). Typically, a family lives on higher ground nearby, shares the swamp with other families, and the swamp income is not the only source of household income. In any case, it far exceeds the value derived from wholesale swamp clearance by local or national developers, since the income from that kind of development usually goes elsewhere and very little of it comes back to local rural people. Maclean’s work supports the impression about wetlands that is gaining ground around the world—that they are valuable resources in more ways than one.

In discussions with African developers, government officials, and aid agencies, the idea often pops up that swamp conservation can be achieved by promoting ecotourism—tourism that brings responsible people to natural areas. This is tourism that not only conserves the environment but improves the welfare of the local people. Ecotourism has great appeal to planners because it holds out the promise of money made, ecosystems conserved, and everyone gaining in a win-win situation. But in practice this successful scenario is only true in cases where a national program is already in place to coordinate the effort and guarantee that the benefits will come down to local levels.

A good example of that is in Botswana, where tourism is a significant income producer and directly benefits people living in the Okavango Swamp. In areas around Lake Victoria, however, tourism has little or no local effect. Lakeside households receive little, if any, of the money spent by tourists on services and handicrafts. In order to be successful, it also helps to have programs in place that provide infrastructure, such as that used in the estuarine swamps in the Sunderbans National Park in India, where nature walkways and a network of bird-watching towers have been provided.

In the case of Lake Victoria, one productive effort is the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Plan that treats the lake as a common natural resource between Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya, and a valuable one at that. The World Bank invested $80 million in the original plan. A second phase of the plan has been announced that will amount to $135 million, with 50% of the funds to be spent through the national governments on socio-economic development.

With infrastructure and promotional plans in place, ecotourism activities might succeed if the featured programs encourage villagers to participate in sustainable-use activities such as mat-making and handicrafts for sale by cooperatives. Papyrus papermaking, as is done in Cairo, might be one of the activities taken up in this way. But all this is for the future. Right now, encouraging traditional multiuse by rural households in a sustainable fashion seems to be the best path toward papyrus conservation in this part of Africa.

Protection and Conservation

Another way of protecting wetlands is to declare them internationally recognized wetlands, or Ramsar sites, as was done in Uganda. This allows volunteer agencies to become involved in conducting conservation education activities and helping local people develop community-based management plans, as well as empowering local fisheries associations to promote sustainable fisheries and tourism. All of which would probably fit well within the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Plan.

One of the Ramsar sites on Lake Victoria is at Mabamba Bay, an extensive swamp in which the globally threatened shoebill (Balaeniceps rex) can be found. The site also supports an average of close to 190,000 birds of many species and is part of the wetland system that hosts approximately 38% of the global population of the blue swallow (Hirundo atrocaerulea), as well as the Papyrus Gonolek (the mnana), the globally threatened Papyrus Yellow Warbler, and other birds of global conservation concern.

Any conservation effort, whether village-based or national-level, would be helped if the lake level were not allowed to drop as much as it does. High water levels help isolate and protect the swamps. Thus, whatever power generation is installed in Uganda should be of the type that requires the most efficient re-use of water. A good start will be the Bujagali hydropower project in Uganda on the Victoria Nile, a power plant that has been installed seven kilometers downstream that reuses the water passing through the two upstream plants. This may well serve as a model. It is expected to generate an additional 250 MW that will allow Uganda to substantially retire expensive thermal generation equipment. Because it is a run-of-the-river facility, it will not require any large storage basin or extensive flooding of surrounding regions.

In the beginning of 2010, one year earlier than predicted, torrential rains fell in the Lake Victoria Basin; suddenly the level started rising and the swamps and fisheries recovered to some degree. The battle for control of the lake’s resources was over—for now. If anything, it showed that Tanzania and Kenya have little or no recourse and virtually no control over a common resource. Any pressure they did bring to bear politically fell on deaf ears. The national interest for electricity in Uganda superseded regional and environmental interests.

And what of the future, when a general drying of the climate is expected? In years to come, the lake will probably go through cycles that will perhaps be even more drastic. Hopefully by then new sources of energy in Uganda will preclude the disastrous recent past, and the swamps surrounding the lake will be sustained to strong enough levels to prevent the extreme runoff into the lake when the flood comes and prevent the nearly equally disastrous water hyacinths and algal blooms.

The time seems ripe to put into practice a long-term conservation effort to protect the aquatic ecosystems of the lake while all three countries are once again in a cooperative frame of mind. And it’s just as well that they are ready to put the bitter past behind them, because a far more serious war threatens as the upstream countries of the Nile Basin pit themselves against Egypt and Northern Sudan over the use of water on the Nile.

In the East African marketplaces, the shopper can often find a light cloth wrap, a khanga, useful for many things and typically emblazoned with Swahili proverbs. One says “Wapiganapo tembo manyasi huumia,” or “When elephants fight, the reeds get hurt,” which is appropriate to the times and the coming war along the Nile.