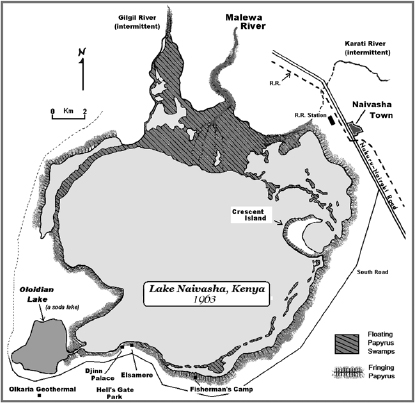

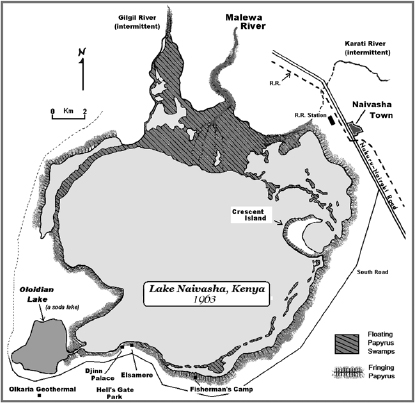

MAP 6: Lake Naivasha 50 years ago.

Blood Roses, Papyrus, and the New Scramble for Africa

Lake Naivasha is unique in Kenya, Africa and indeed the world. It is presently faced with some severe problems which threaten its very existence as a lake and a wetland.

—David Harper, 2005, Lake Naivasha

Riparian Assoc. Newsletter

Two thousand machete-wielding men swarmed onto the main road like colonies of angry African bees roused from their hives, determined to kill in defense of their own. Yelling and screaming insults, armed with the traditional all-purpose farm tool of the Kenyan farmer, the razor-sharp panga, they were ready to show anyone and everyone that they knew how to use it. A handful of policemen fired into the air, hard pressed to control the mob. Now, some of the mob broke away and chased the opposition.

On one side of the road stretched Lake Naivasha (Map 6, p. 192), where at the water’s edge one can see papyrus swamps—the sacred sedge, its umbels rising above the mud and water of the lake where, like the human combatants, it is also fighting for its life. Papyrus is the main component of the wetlands of this lake, and it is dying for lack of water—water that is being drained from the lake to grow roses.

On the land above the road not far from the surging masses are roses in bud, millions of them, red, beautiful, moist, and exotic, grown here by commercial growers who stood to lose a fortune unless the fighting stopped. The resources that feed the roses are also the lifeblood of the wildlife and the papyrus swamps of the lake. Without the lake’s water, the roses will die.

To an outsider, there is no way of telling who is who in this mob. The men who are fighting are not wearing distinctive jerseys; if they were, they would be blue for the waters of Lake Victoria and Kisumu, the principal city in western Kenya, the homeland of the Luo, and green for the corn and coffee trees of the Kikuyu, the opposing side, who claim Nairobi as their enclave.

These ethnic clashes came in the wake of a disputed presidential election. First, the Kikuyu were harassed, burned out of their homes, and murdered in Kisumu; then in January 2008, the Kikuyu turned on the Luo. The place they had chosen to do so is significant: a large slum called Karagita on the shores of Lake Naivasha. Some sixty miles northeast of Nairobi, just south of Naivasha town (Map 7, p. 194), it is a place in which 60,000 or more people live. Most work on the flower farms that have taken over the land around the lake.

Overhead, Kenyan military helicopters firing rubber bullets swoop on the crowd, and the wind from the chopper blades sends waves of turbulence out over the papyrus and rattles and shakes the plastic sheeting that shields the roses from the blazing African sun.

What makes this scene so bizarre is that it is being played out in the vicinity of a Rift Valley lake that was once known in colonial days as the ideal vacation site, a playground of the rich and famous, formerly one of the safest places you could go for a weekend in Kenya. Still a popular place for seminars, meetings, and international conferences, 22 people were killed here during the weekend of the riot. Nineteen of them were Luos whom a gang of Kikuyus chased through Karagita and trapped in a shanty that they set on fire. The others were hacked to death with machetes, according to the Associated Press.

MAP 6: Lake Naivasha 50 years ago.

Like the plant symbols of Upper and Lower Nile, papyrus represents the wildlife conservation interests of Kenya while the rose, in place of the lotus, stands for Kenya’s economic business interests. Both plants wait now on the sidelines for this awful conflict to resolve itself and for the country to become whole again. It will not be easy. As of March 2008, more than 1,500 people had been killed in Kenya and 600,000 forced to flee their homes. Part of the tension that led to this fighting in Naivasha can be traced back to jobs, conditions in the local slums, and a scarcity of natural resources. Water, be it for roses or papyrus or people, is inextricably bound up in the welfare of all living things in this region: human, plant, and animal.

Even now the conflict simmers under the surface; it is far from over.

Not long after my arrival in Kenya, I found the lake to be an ideal research site, a place where papyrus grew in profusion. Located in central Kenya, it is a place that in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s was a feature of “. . . the hunting grounds of the hedonistic Happy Valley set.”

Joy Adamson, the author of Born Free, still lived on the shores of the lake, and it was here that some of the scenes in the Adamson films about Elsa the lion were shot.

In the late ’70s, Kenya was a different world, a world that belonged to President Jomo Kenyatta. Certainly, I thought, it would be easier to get by here on this magical lake than in the corpse-strewn swamps I’d left behind in Idi Amin’s Uganda.

At that time, Lake Naivasha was not a major tourist destination, but it had the potential to become one. Unlike Lake Nakuru, the famous flamingo lake 35 miles to the west, which is a national park, Lake Naivasha was owned by private interests. It had escaped being designated a national park, as many think it should have been, since all the land around the lake was in the hands of white settlers or wealthy Africans or expatriates, all of whom enjoyed the privacy conferred by owning hundreds of acres of exotic landscape. Years later, the lakefront farms began changing hands as the original owners sold to a new crop of buyers: European flower companies and rich African investors, who now had exclusive rights to the lake edge and thus controlled access to the water.

The intensive development of the cut-flower industry followed during the ’90s and into the 2000s, so that today over 1,000 tons of vegetables and cut flowers are flown out of Kenya every day, seven days a week. Almost half of these are roses that come mostly from Lake Naivasha.

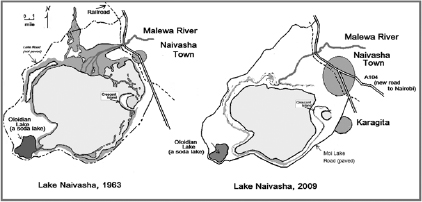

To support this production, the lake’s population of workers shot up from 20,000 to 350,000 within the space of ten years and the town of Naivasha expanded to accommodate them (Map 7). Slums also mushroomed along the road between the town and the main flower farms. A boomtown mentality developed and the crime rate rose, including the tragic murder in 2006 of Joan Root, a conservationist and Oscar-nominated nature filmmaker.

MAP 7: The general reduction of Lake Naivasha and change in wetlands and the towns. Since 2009, the water level has come back up, but the wetlands are gone.

Joan noted in her diary the murders of three friends and neighbors, and a police report that the number of armed robberies had risen to eighteen a month. It is here that Joan and her husband Alan Root established a haven for orphaned animals, but in 2006 she was gunned down with an AK-47 in her bedroom, struck by five bullets. As Mark Seal tells us in his Vanity Fair story,1 blonde, beautiful, and fearless, she had been idolized for the pioneering wildlife films she made with her husband. After their agonizing divorce, she devoted herself to an even more dangerous mission: saving her beloved lake from the ecological ravages of Africa’s lucrative flower-farming industry. Her murder is believed to have been a contract killing, but the questions of both who fired the shots and who paid for the assassins remain unanswered.

I spent five years on this lake carrying out research on the once-plentiful papyrus swamps that ringed the lake, and I can well imagine the feelings that move people who want to act to save the lake. In Joan’s case, her story lives on and has recently attracted worldwide attention. Thanks to Mark Seal’s book Wildflower, Joan’s life will be the subject of a film starring and produced by Julia Roberts. And it will be shot on the lake against a background of the lake and its wildlife, with one exception—the papyrus swamps that were a prominent feature of the lake in Joan’s time have mostly disappeared.

The publicity that comes from the movie will show the world what happens when resources become scarce and tempers flare, but it won’t save the lake. That task can only be accomplished by the people who live there, who at present are at one another’s throats as they scramble for water.

Who are they? The most influential are the flower growers, a consortium of European investors, managers, technicians, rich Kenyan backers, and shareholders. They supply over 33% of the cut flowers in Europe, and the foreign exchange they earn gives them the political power to draw water with few restrictions. They take what they want from the lake and pump what they want from underground, using boreholes that tap into the lake’s aquifer. The permit system under which they are regulated has little meaning in the face of their effect on the national economy. A rough estimate of what the growers take from the lake amounts to three to four times the “safe yield,” the amount that could be taken from the lake without disturbing the lake balance.2

In time, the growers were pitted against the local town of Naivasha that provides domestic water to the burgeoning crowd of workers and service providers. A complicating factor is that the aquifer that recharges the lake is the same one that is contaminated by seepage and runoff from unsewered town houses, slums, and flower gardens.

Water is also demanded in quantity by a local geothermal plant that needs water to cool the very hot water taken from the geothermal zone under the earth. This means more water lost from the lake. Whenever the lake begins to shrink, the geothermal use does not stop. The plant takes its water from the deepest part of the lake and therefore is in the best position to take the very last drop.

Another scrambler is 35 miles distant, the town of Nakuru, the place west of Naivasha that hosts the famous flamingo lake. A major tourist destination, it also supports a local industry that provides vegetables for the capital city, Nairobi. Irrigated agriculture and domestic water requirements make Nakuru a priority user. Consequently, it has permission to draw water out of the Malewa River before it even enters Lake Naivasha.

Lastly are the thousands of newcomers eking out an existence in the slums that have sprung up along the lake edge. By and large, the slum dwellers are bound to be the losers if things continue the way they are going, since they have virtually nothing but their rights. The Kenya Water Act of 2002 requires the government to provide water services to consumers. However, those living in the slum at Karagita have neither the funds nor the technical equipment to tap into the aquifer, or to pump the water of the lake even though it sits a short distance away. When they do acquire the means to exert their rights, they will be a force to be reckoned with.

To make matters worse, a drought set in during the early part of this millennium and the scramble for water coincided with a scramble for land to grow food. Any land not owned by the flower industry was farmed or grazed, so that as the lake retreated so did the destruction of the vegetation. The flower growers cut trenches to reach the receding water of the lake; in the process, the papyrus swamps on the lake were decimated.

In 2010, the rains predicted by long-term weather cycles fell early and the drought was broken. Now the lake is re-flooded along with the former swampland and hopefully papyrus will recover from seed, but the future is far from certain. Perhaps it is prophetic that the town, region, and lake were called “Naivasha,” after the Maasai word Nai’posha, meaning “rough water,” because during any storm the normally placid surface of the lake can change within minutes.

The violence witnessed by Joan Root a few years ago was an indication of the tension that continued to rise as the lake dried and the earlier drought wore on. Her neighbor on the lake, another conservationist, Lord Enniskillen, told Mark Seal: “The tragedy of her death is that she died trying to alleviate that very poverty which creates the insecurity around here.” Some people thought of her as an enemy because she was trying to save the lake and thus keep water from reaching these “blood roses.” The anger spilled over following the election, with levels of violence never before witnessed. Surprisingly, during that time, we are told by former head of Kenya Flower Council (KFC) Erastus Mureithi, the country saw a rise in the production of flowers. This was possible because urgent measures were taken to address the situation, such as flying the flowers directly from farms to Eldoret, a town further west with an international airport. Then they were flown to Nairobi for onward transmission to Europe, as opposed to the normal route using the road. Although some workers were displaced by the violence, especially in Naivasha, Mureithi said new ones were hired immediately “to ensure the labor-intensive business of floriculture was not interrupted. The sector has performed admirably in difficult times, underlining the resilience of the Kenyan people and the economy to survive even at the worst of times.” And the major water users continue to draw water in unreasonable amounts.

The rioting that followed the disputed national election is a foretaste of what could happen if the lakeside economy collapsed. One thing that could trigger this would be the European flower market. If it were to bottom out, or shift to another supplier (Turkey and Ethiopia are good possibilities), chaos would reign in Naivasha and Kenya.

What can be done? Putting a halt to new drilling or new water permits is only a short-term solution. The lake is in desperate need of a long-term plan for water use and conservation that can be implemented—and sustained—locally. That does not happen at present, so the scramble for water in Naivasha continues.

Lake Naivasha has always been a beautiful place. I first came there on a drive back to Uganda from the Kenya coast when I found that it was almost halfway, an ideal stopping point.

The Lake Hotel where I stayed is a very comfortable place that fronts on the lake. When you wake in the morning, hundreds of birds greet you as you look out over a wide expanse of lawn. More birds await as you walk in the shade of the fever trees. One of the prettiest is the Superb Starling (Lamprotornis superbus), a glossy-feathered, iridescent little creature, blue with a white-banded, rusty-red breast. Quite bold, several will land at once on your breakfast tray on the open verandah.

In contrast, strutting around on the lawn is the ugliest bird you’ll ever see, the Marabu Stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus), a frequenter of the hotel garbage pit. It is an amazing sight with its scrofulous, fuzzy head and large dirty-looking beak, still filthy from picking over the trash bits.

At the water’s edge are sacred ibis and goliath heron that move among the coots, ducks, and pelicans in the shallow water. Jacanas, sure-footed, long-toed birds, run quickly across the floating lily pads. Above them in the trees and soaring out over the lake are fish eagles, their cries echoing in soul-piercing calls that carry across the lake, especially eerie in the morning mist. Late in the afternoon, Mt. Longonot, the volcanic hill in the background above the lake, turns purplish blue-red and stays that way until the sun sets. Just off the shore is Crescent Island, the rim of an extinct volcano and a self-contained game park that was used for filming the lions in the Adamson-inspired films, like Living Free. Once the water was high enough to isolate the island, the lions could be let loose to roam since, like many cats, they hate the water.

It is obvious from the start why the Happy Valley crowd loved this place and why settlers and expatriates soon bought up every inch of shoreline, making it a private enclave. The lake was noted for its papyrus swamps, which covered twenty square miles and ringed the fifty-five-square-mile lake. Shortly after I moved to Nairobi from Uganda, I came to the lake almost weekly to take samples and make observations. Tourists from Nairobi would show up on weekends, followed by the occasional expatriate bass fisherman loaded down with sophisticated equipment. Backpackers and campers stayed at Fisherman’s Camp, a lovely place in the south. Not far away was the YMCA camp that hosted busloads of Nairobi school kids every weekend.

In all, it was a great place to get away to.

The first European to arrive on the lake was Gustav Fischer, a German explorer who in 1882 was looking for a route from Mombasa to Lake Victoria. With the advent of the railway in the early 1900s, it became a popular weekend spot for European residents. They came out by train on duck-hunting parties from Nairobi to take advantage of the teeming birdlife associated with the papyrus swamps. The small mansions and spacious bungalows that sprang up around the lake were on plots of land often large enough to support herds of game. Many were working farms with dairy herds, breeding cattle, crops of alfalfa and vegetables destined for a local drying plant. Tourists stuck to the eastern shore and the paved road. The peripheral road on the west side was a wide, dusty, potholed track that discouraged road travel. Once the land was bought up, the lake virtually became private property, and the expatriates wanted it to stay that way. During the week, after the tourists had gone, I often found I had the lake to myself. And what a strange and lonely place it was. I worked in the large swamp that once covered the whole northern part, though I also visited swamps in the south, where a white-painted Moorish-style castle, called the Djinn Palace, towers above the shore. It can still be seen from most places on the lake and acts as a marker for navigation as well as a reminder of history.

“Joss,” Earl of Erroll, the lady-killer of the film and James Fox’s bestselling book White Mischief, lived there from 1930 with a string of exotic visitors, such as his lover Diana (Lady Delamere). He was shot in Nairobi in 1941, presumably by a jealous husband. After his death, the Djinn Palace was rented out to Lord Braughton, the man accused (later acquitted) of killing him. Later still, it was bought by Baron Knapitsch, a famous trophy hunter, and today it is owned by Oserian, one of the major flower-growing companies in the area.

Further to the east lived Alan and Joan Root. Then came Jack Block’s place; Block was a local hotel magnate who owned the Norfolk Hotel in Nairobi and, previously, the New Stanley Hotel and the Lake Hotel (the last was later owned by Michael Cunningham-Reid). On the west side is Joy Adamson’s house, Elsamere, set in a grove of thorn trees with Colobus monkeys scampering about and a spectacular view of the lake. Still further west are the farms of Iain and Oria Douglas-Hamilton, famous for their elephant studies; Mirella Ricciardi, the photographer, and her relatives the Roccos; and the cattle and wildlife ranching family the Hopcrafts.

What did they all have in common? Besides being famous, white, and well-connected, they were ardent conservationists. When they met at the Naivasha Sports Club, they invited people like me to come and talk to them about how the lake could be maintained just as it was, even though forces were already in place to bring about enormous changes. The first indication of this change was the advent of the flower growers, whose farms were already attracting international investors.

And the Africans? Where were they in all this? When Gustav Fischer arrived in 1882, he was met by Maasai warriors in full battle dress, ready to repel him and his party. He promptly turned and fled. After that, the settlers and the British Army arrived, and brought with them their Somali and Swahili house servants. Before long, Maasai, Luo, Kikuyu, Kalengin, and Akamba were working the farms, tending the hotels, and cleaning the houses, while a few rich African businessmen and politicians were buying into the development of the local farms and hotels and, later, the flower business. Some of the African farm workers rose to management level and occasionally some even became landowners. Whenever a settler or expatriate would sell, there was always a willing African buyer, but in general it was a white colonial world and the total number of Africans did not change much. The town of Naivasha remained a sleepy, dusty place for many years.

During all that time, from the ’30s well into the ’80s, the birdlife and swamps that ringed the lake remained its most interesting feature. What attracted me was the large North Swamp that spanned the delta of the Malewa, the only perennial river entering the lake. This swamp, an almost pure stand of 9,000 acres of easily accessible papyrus, was a magnificent sight. To my eye it was a paradise; for bird watchers it was the jewel of the lake. But the same volcanic soil on which these wetlands thrived was also ideal for the cultivation of export-earning cut flowers and special vegetables for the European market. With a virtually free water supply directly available from the lake or easily pumped from nearby boreholes, a year-round growing season, and an unlimited pool of cheap labor, it was a money-spinner from the start.

Enormous numbers of workers settled near the farms along the road to the east of the lake, now called Moi South Road. Into these areas came thousands from all over, lending truth to the idea that this would be the melting pot of Kenya, the place where all tribes would benefit from the economic miracle and settle down together to enjoy the fruits of uhuru, the Swahili word for “freedom.” This was not to be. The Maasai were right: “rough water” describes what could—and did—happen as the lake started to change. Further portent was seen in the local volcanic geology. With the active fumaroles and steam vents in the south not far from an eerie-looking rock formation aptly called Hell’s Gate, the place always seems poised to blow at any minute, either from nature’s fury or man’s.

The road to Lake Naivasha from Nairobi lies on the main route that goes across Kenya from the coastal city of Mombasa to Uganda. For years the road was dangerously potholed and narrow, its edges cracked and broken in many places. The one section most familiar to me was the part that followed the twists and turns alongside the path of the old railroad, which once wound its way up and down the Rift Valley. The modern tracks follow a more direct route.

Arriving at the rim of the escarpment, before descending I would catch my first glimpse of the lake on the valley floor, glinting dark blue in a brownish-green landscape, and overshadowed in the morning light by Mt. Longonot which loomed to the east.

In the late ’70s, this old road was replaced by a new one, a modern highway that went straight along the high ground above the valley rim. Trucks were not allowed on the new road, which made driving easier. My first trip on this clean, dark black surface with its bright white stripes and new route signs was enough to resurrect the joy of driving. And the landscape! After running through a large upland forest reserve, where the foggy, cool, moist air had to be whipped off the windshield by the car’s wipers, the road emerged along the sunlit edge of an 8,000ft-high escarpment. The panoramic views of the Rift Valley were astounding. It was easy to be distracted and before I realized it I had arrived at the new turnoff, a road that took me down into Naivasha town which, at 6,000ft (about a mile high, like Denver), was still high enough to leave me breathless after a brisk walk.

Along the road coming down to the lake, I saw the Kinangop Plateau up-close for the first time. This is a grassy tableland that has been populated by Kikuyu settlers. In the early ’60s, they were given land titles and working plans for their new acres, but because it was a wet area with tussock grasses interspersed with bogs and marshes, the land had to be drained. This process, started in colonial days and carried forward by the new settlers, is now so complete that today there is very little of the original grassland left other than a small park. The farms here include fields of pyrethrum, the daisy ingredient of natural insecticides, and mixed crops of which the potato dominates. I saw few trees but many, many productive small farms. And at every country bus stop, or “matatu” stand (local taxis or minibuses), I saw large sacks or “debbies” (4-gallon capacity tin containers) loaded with potatoes and carrots, and open trucks piled high with produce.

Ultimately, the water supply of the lake comes from these areas—the Aberdare Mountains in the north and the Kinangop Plateau in the east, both regions that sit high above the basin. In the ’80s and ’90s, the foothills of the Aberdares were cleared and cultivated by Kenyans who settled the land and produced food in significant quantities. They also farmed on the plateau where, in 2005, in one district alone farmers produced 1.7 million tons of Irish potatoes.

Rain falling on tussock grasslands, the original natural vegetation, infiltrated the soil and recharged the rivers in a natural fashion. The water seeped into the aquifer that fed the streams, resulting in an even flow distributed over the course of the year. This natural landscape provided water from the land—until the cultivated plots took over. After that, the water was drained away and used for crops in the western highland.

Today these highlands lose a great deal of water through crops and evaporation from exposed soil. As a result, during floods water now comes straight down the denuded slopes. When it enters the streams, hydrologists find, the annual flows are greatly diminished and the water is soil-laden. This is the very soil that will continue to kill the lake now that the swamps have been cleared. The only recourse is to build very expensive sediment traps unless the papyrus swamps are replanted and maintained as filter swamps. As productive as these areas are, they have changed the water cycle for the worse, which is now eroding away the soil and affecting the lake.

When the flower farms arrived in Naivasha, no one was ready for what happened. Neither the town, the settlers, hotel managers, nor flower farms had the services to cope with the phenomenal growth that resulted as the market for Kenya flowers soared. The result was pollution on a massive scale from intensive agriculture, as well as sewage and runoff into the lake. In addition to the problem of pollution, water was being pumped from the aquifer and from the lake faster than it was coming in. It was like inviting a large number of people to a party, then turning off the beer taps. But instead of questioning why the taps were turned off and insisting they be turned on, people scrambled to draw from what was left at last call. Everyone needed water, and everyone had a good argument ready as to why they should be given precedence over others. Even today, years after the deterioration of the lake, few reports or news stories have taken up the question of why the water that was supposed to feed this massive development disappeared. Much of the water that went missing was, and still is, siphoned off before reaching the lake. It is converted into the food that feeds the people in the uplands and supplies the markets in Nairobi and international exports. Thus more and more is consumed in Nairobi and sent to Europe, and less and less is allowed to go on its way into the lake.

In earlier times, there were three rivers—the Malewa, the Gilgil, and the Karati (Map 6, p. 192)—all of which were fed by rainwater flowing down from the Kenya Highlands. With time, irrigated agricultural schemes developed along all these rivers. Lower down in the basin, water was pumped from the aquifers using boreholes, or pumped directly from the rivers. At the same time, the development of farms on the foothills of the Aberdares and the Kinangop went on unabated. The Gilgil and Karati became intermittent, and then stopped, and the flows in the Malewa were diminished. All this was happening well before the flower farms got under way.

Just before heading back to Nairobi, I remember stopping one day at a farm stand in Naivasha where I bought three cabbages and put them on the back seat of my car. Driving off, I happened to look back at them in my rearview mirror and realized they filled the whole back seat. What I was looking at was an example of what the flower growers saw in the great potential of the Naivasha soil, but instead of cabbages they had their eyes on cut flowers, especially roses. The prices were high enough to evoke dollar signs before their eyes. They went to bed at night dreaming of the profits that would come about when they brought together the volcanic soil of the lakeshore, the abundant supply of fresh water, and roses that could be shipped by air to satisfy an enormous market that peaked on St. Valentine’s Day; and while they dreamed, the lake dried.

Popular thinking was that the multi-million-dollar market would change Kenya the way outsourcing has changed Asian countries. Environmentalists both locally and internationally were outraged at the impact that was evident from the start. Unfortunately, their recommendations had only a minor effect, and the government seemed powerless—or unwilling—to stop the onslaught. Perhaps this was because the people working on the farms, the owners and managers of the flower farms, as well as businessmen and workers throughout the country did not think of what was happening as an onslaught. After all, this was no different from the coffee and tea farming that had gone on for a hundred years in Kenya. To most Kenyans, the farming and marketing of flowers was as natural a business as any other agroindustry. Coffee growing had even been romanticized by Karen Blixen in her famous book Out of Africa.

The coffee industry in Kenya uses a wet method that requires a great deal of water, with the growers applying a variety of chemicals, resulting in coffee farming being the number one major polluter of surface water in the country.3 Pollution is not an obvious concern because the coffee farms are located in rural areas where more than 77% of smallholders who produce the crop are located. Coffee and tea growing are part of everyday life. Flower growing on Lake Naivasha was just another industry, though more obvious. It would be hard for Kenyan environmentalists to make a case, but the number of Greens in Kenya has grown steadily over the last forty years. There are now Schools of Environmental Science in the colleges and universities, concepts of conservation and ecology are now taught in the grade schools, and this new generation benefits from the earlier efforts by animal conservationists in Kenya, who showed them how they might succeed. Burning large piles of ivory at public bonfires to show that the illegal trade would not be tolerated, making movies like Born Free and Serengeti Will Not Die, and writing books like Among the Elephants were examples of how to attract attention and promote solutions. Wangari Maathai’s 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for her contribution to sustainable development in Kenya proved to everyone that much could be achieved in this area. It also helped the environmentalists’ cause that Lake Naivasha is the only freshwater lake in Kenya, and thus had a distinct fauna and flora. All the other lakes are soda or saline with a balance of salts and natron that make them unpalatable.

Lake Naivasha was fresh, visible, and vulnerable, and the environmentalists were ready to fight. They retaliated early against those who placed commercial interests first by making the lake a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance in 1995. This is a move that if followed with action allows for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources. But, although elsewhere it is effective as a technique to slow the misuse of wetland resources, in the case of Lake Naivasha it had little effect. Perhaps because Lake Naivasha is not a national park, it cannot be easily legislated or regulated. The Naivasha Ramsar site consists only of the lake and a buffer zone that includes the swamp fringe surrounding the lake; it doesn’t include the land or the flower farms. But this doesn’t absolve the flower farms from their negative impacts. Unlike the Kenyan coffee and tea plantations which affect river water outside of protected areas, the flower farms border on an internationally designated wetland. This made it doubly important that the flower farms take precautions, as their impacts are felt directly by the fauna and flora of the lake.

This arrangement whereby they were allowed to continue farming around the periphery of the lake was made in order to accommodate the fact that the lake is entirely surrounded by private land. It was left to the community to voluntarily look after its lakeside interests, which apparently did not happen.

Tension increased between the different players in the environmental scenario during this period. One person who stepped in and took matters into her own hands was Joan Root, one of the leading lakeside conservationists whose murder signified the end of the expatriates’ splendid isolation. They—and the rule of law—were no longer any match for the Yukon gold-rush atmosphere created by the flower-growing industry.

The next startling event was the disappearance of the papyrus swamps. By 2008, over 90% were gone. Among the swamps lost was the large one of 9,000 acres in the north, shown on Map 6 (p. 192). Its disappearance was clearly evident on satellite photos and the latest maps (Map 7, p. 194). This was shocking news, because this swamp had been the subject of research for over thirty years, five of which included my own work. In recent years it provided a habitat that attracted more and more attention from African biologists. But now all of that is history, and in its place a complication presents itself.

With the papyrus swamps around the lake gone, there are no longer any barriers to the influx of sediment and pollutants. Any rainfall will bring increasing loads of nutrients directly into the lake, which is already at its breaking point.

By the beginning of 2010, after the swamps were gone, the drought ended, the El Nino rains arrived, and instead of the lake snapping back to its normal self, 700 fish died due to lack of oxygen caused by fertilizer runoff and algal blooms.

This fish kill outraged local residents, who believed that the flower farms had dumped some chemical into the lake. Subsequent examination of the fish and dissolved oxygen in the water proved conclusively that eutrophication was the cause of the fish deaths. Dr. Stephen Mbithi, a marine expert, said that the vast majority of fish had died with open mouths, and that the larger fish had died first, followed by smaller fish. This indicates suffocation and a lack of oxygen due to algal growth. It also indicates that sewage had been flushed into the lake and that now the lake was well and truly polluted. Ultimately the culprits were the towns, the irrigated schemes upriver, the flower farms, and agriculture in general.

During the past fifteen years there have been several efforts made to protect the lake and the swamps and to educate the people living within its 1,235-square-mile catchment. This work is coordinated by the Lake Naivasha Riparian Association (LNRA), an association of local landowners who own land abutting the lake. Started in 1925, it was reorganized in recent years to include among its membership hotel owners, tour operators, the Kenya Power Company, ranch owners, flower growers, small farmers, domestic plot owners, cooperatives, and the Naivasha Municipal Council itself.

One of the most important actions of the association was the development of a management plan for the lake. Since all the major lakeside landowners belong to the LNRA, it was the ideal group to guide the plan, which was meant to control human activities in the area and stem any decline of the quality and quantity of the lake’s waters. Adopted in July 1996, the plan was updated in early 1999. It commits members to monitor all activities on the riparian land (land exposed in times of dry weather), to protect the papyrus belt, and to observe a 100-meter “buffer zone.” Shortly thereafter, the plan was declared not legal, and in its place the government turned to self-regulation to conserve the lake. The flower farms were told to execute their own conservation plan through a Water Users Association.4

Would the flower farms ever be able to rise to the occasion and clean up their industry as well as help in restoring the lake? Will there ever be a White Knight who will rescue the situation? Until now this was considered too far-fetched. It would never happen. But it seems there may be some relief in sight—which is fortuitous, because the water level of the lake is currently higher than it has ever been, and perhaps this is the best time to institute changes before the next drying cycle takes the lake down to new lows.

Among the rescuers, Kenya has a model flower farm that can show everyone the way of the future. It is no ordinary farm, but one that is well on its way to becoming an international model of how to run a flower farm in a sustainable way. The farm, called Oserian, is unique. It was formed in 1969 as a family concern producing vegetables; it later evolved into a cut-flower farm in 1982.5 The owner, Mr. Hans Zwager, and his wife and family have devoted themselves to doing things the right way. They rank today among the top flower farms on the lake in terms of production, yet they rank over the top environmentally.

The farm is located on an estate that includes an 18,000-acre wildlife sanctuary and a 3,000-acre wildlife corridor that allows game to safely pass from the lake south to the man-made water holes of Hell’s Gate National Park. The 620-acre flower farm run by Peter Zwager represents less than 5% of the total estate and yet, because it is run so efficiently, it has a smaller carbon footprint than comparable greenhouses producing flowers in Holland. By using a combination of plant nutrition with bio-control agents designed to prevent and combat a range of diseases that affect flowers, Oserian has become one of the world’s largest Integrated Pest Management Flower Farms. With one 2½-acre greenhouse devoted to producing, each week, more than three million Phytoseiulus persimilis—parasitic mites that attack spider mites—it saves millions each year on chemicals alone. They use natural ventilation and steam release to prevent mold buildup and thus also save on fungicides.

By far the most astonishing advance at Oserian was its move to tap into the local geothermal vents, the geological formation that gives Hell’s Gate Park its name. The geothermal turbines make the estate energy self-sufficient, while the carbon dioxide from the same well is used to drive productivity in the greenhouses to higher levels. The steam from their geothermal plant also helps control the relative humidity and temperature in the greenhouses; this in turn reduces and regulates water requirements so the plants receive only what they require from drip systems. The roses are grown hydroponically using an inert substrate made from pumice stone mined and crushed locally on the estate. This same system allows them to control the pH, nutrients, and nutrient strength of the water in which the flowers grow, water which is then collected and recycled, along with any estate waste runoff, through a filter swamp. All of this is supplemented with a rainwater collection system. In sum, they take a minimum amount of water through metered boreholes, the ideal green industry. To top it off, they have planted 300,000 trees to make the area a better place to live!6

And the work force? Oserian is Fair Trade Certified, which means that the farm must continuously improve conditions for the workers—whether it’s their pay or how they live. The 4,800 farm workers plus dependents live near the farm in free or subsidized housing, with health and primary education provided along with nurseries for day care. They pay the highest floricultural wages in Kenya and help with local village water projects and schools.

In the final analysis, it must be said that Oserian and a few other sustainable farms locally are in the minority in the Lake Naivasha area. The majority of growers do not farm sustainably, so although Oserian has shown everyone the way, it’s now up to the government to act.

It would also help if the towns (Naivasha and Karagita) would close ranks with the Riparian Owners Association, the Growers Group, and responsible sustainable development groups like Imarisha in order to help the poor and rural communities to obtain water, sewerage, and garbage recycling services within the lake area.

Another encouraging effort is the plan to construct a filter swamp across the delta of the Gilgil River. Because the Gilgil flow is intermittent, a series of levees, dikes, and barrages can be put in place. The idea is to create a filter swamp and keep it flooded year-round to allow papyrus to grow there. These newly restored papyrus swamps will be confined to flotation devices made of recycled plastic water bottles; this way the swamps will continue to float even as the water levels decrease. The swamps would never again be stranded where they could be subjected to cutting and burning. The restoration program has already begun under the guidance of Ed Morrison and David Harper, researchers who have worked on the lake for many years.7 They also propose that the papyrus restoration program be supplemented by projects that rehabilitate the catchment and restore degraded habitats along the rivers and around the lake edge. The cost of the program would be partly borne by the flower farms.

There is no reason why papyrus filter swamps could not be set up to filter individual farm wastewater. Managed by individual flower growers, the size of the filter swamp would be proportional to the company’s operation. Swamps so created could provide the basis for a sustainable local craft industry, as well as birdwatcher sites and ecotourism. Cultivating, harvesting, and promoting such a system would be an easy task for business interests that handle millions of dollars in export sales, and are capable of surviving and even expanding in the face of civil unrest, droughts, and disasters that would normally level other agribusinesses.

A major effort by the growers in this regard would show the international environmental community that the roses from Kenya are not simply the “blood roses” of the sensationalist press, but the product of an integrated and coordinated system that involves local people and cleans up its own environment.

Thirty years after the fact, as I thought of the damage that came about when the swamps were cleared, I also thought of the thousands of hungry Africans who live there and are always in search of land. I realized then that whatever solution is found must be resolved in favor of these people. It does no good to conserve and restore a natural resource if people starve to death in the process. The current scramble for land in Africa is an example of how big business goes about the kind of development that brushes aside such scruples.

Today the restoration of the Everglades is seen by the World Bank as a paradigm for sustainable development and a worldwide guide for resolving global water conflicts. For others it is also a restoration blueprint for America. One of the objects of this book is to illustrate the importance of papyrus, and to show that papyrus is really worth conserving as a resource for the future. The plant that involved us in one of the oldest human-plant relationships in recorded history now depends on us for its vitality. This is a trust we cannot ignore.

There is a haunting coincidence between the cutting and clearing of swamps today in the rest of Africa and the clearance of papyrus in ancient Egypt. A thousand years ago during the Islamic Era, arable land in Egypt was as much at a premium as it is today. When farmers cleared the swamps, they did so because of the demands of their Arab conquerors. To the people who amassed great wealth from Egyptian agriculture and lived in palaces in the emerging city of Cairo, the swamps were simply distractions. Papyrus lost value with the introduction and substitution of other materials, and then succumbed when agricultural pressure came to bear. The North Swamp of Lake Naivasha in Kenya disappeared for the same reasons—the increasing value of cash crops and the demand for local market commodities. In the case of North Swamp, the water supply was used for agriculture, which was deemed more valuable than the biota of the lake. In Lake Victoria, the swamps are pitted against the value of water needed to generate energy. It obviously comes down to the perceived value of a natural resource and actual value, which is often only apparent in the long term.

In the Huleh Valley, a national investment of $25 million in 1993 made a world of difference in the integration of papyrus swamps with ongoing development and a way of life. In Africa, national economic resources at that level are often not available, and when they are, they are more properly earmarked for general development. In order not to detract from needed general development, or from resources that are scarce already, the cost of stopping and reversing pollution in Lake Naivasha must be borne by the major agricultural and industrial users. That is not likely to happen immediately. Even with a flower export market worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually, it will be difficult to institute a “user pays” attitude. Thus, scarce financial capital combined with the reluctance of those involved leaves the conservation of these common resources, such as the swamps of Lake Victoria and the wetlands in the Okavango, Congo Basin, and Southern Sudan, in the hands of regional environmental initiatives and tourist development agencies. The situation will stay that way until the perceived value of papyrus swamps comes closer to reality, and when the swamps can pay their way once more. Would such a thing ever happen? It did in the Huleh Valley, where papyrus now thrives and does its duty filtering the water. There the water table has risen, alleviating local agricultural concerns, the plant and animal species have blossomed, and birdlife in enormous numbers has returned. Diversion of peat water and local sewage into treatment plants and subsequent use for irrigation are expected to reduce the flow of nitrates by at least 40% annually. The same may yet happen in Cairo, once enough filter swamps are in place. Elsewhere . . . there is hope.