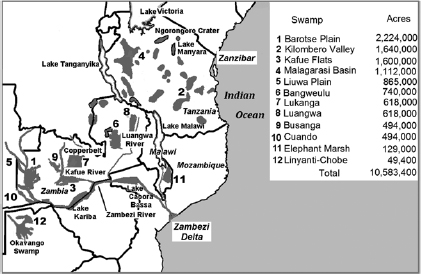

MAP 8: Major swamps of the Zambezi region.

The Zambezi, the Victorians, and Papyrus

Initially the Victorian explorers were searching for the source of the Nile, a task taken on by John Speke first with Richard Burton, later with James Grant. By the time Samuel and Florence Baker made their trip to the upper reaches of the Rift Valley, West and East Africa were already considered “done.”

Attention shifted to the area east of the Congo and south of Lake Victoria, a region that today comprises Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique, and parts of Tanzania (Map 8, p. 213), the cradle of the Congo, Nile, and Zambezi Rivers.

Typically, this area was reached by caravan from the island of Zanzibar on the coast, going due west along paths established by slave traders, who were still active in the region. Tales of exotic mountains, tribes that defied imagination, savannas with unending herds of game, river valleys and water in profusion, including a cluster of large and small lakes still unknown to the outside world, drew the explorers here. By far the greatest attraction was the fact that somewhere among these lakes or rivers was the ultimate source of three major rivers. Could it be that there was a common source? That possibility added heat to the already fevered Victorian imaginations.

MAP 8: Major swamps of the Zambezi region.

The arrival of Livingstone in the region caused much interest and excitement back in England. A scientist and bush doctor, he was also a man born of the working class and an explorer who discovered a waterfall and named it after his queen, yet who, on the other hand, advocated the reform of Empire. A cherished example of the missionary activist, he advocated the expansion of commercial interests yet crusaded against slavery. To the Victorians he was Everyman’s hero, and his motto summed up everything he and they stood for: “Christianity, Commerce, and Civilization.”

When he landed in Zanzibar in 1866, he was getting on in years. It was already thought that he would not have many more African treks to follow. From Zanzibar he traveled west and north, exploring and sending back reports. Just to be on the move was a bracing experience for him. His party was smaller than most expeditions, and by necessity he sought out and relied on the help of Arabs at every turn, people who were obviously connected to the slave trade. Though criticized for this association, it allowed him to report in full on the actions of the slavers while simultaneously providing details of geography and natural science.

He sent his letters and reports back to the coast by runner, thence by boat to Zanzibar for onward transmission to London and the world. The reports made exciting reading and provided facts and eyewitness accounts of cruelty that supported the ideals and fueled the arguments of a growing anti-slave lobby. And so, for five years he explored.

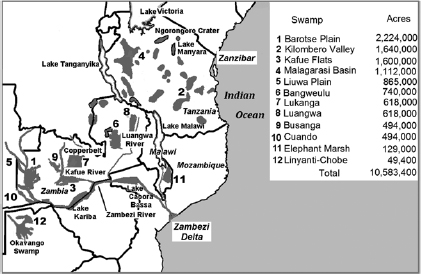

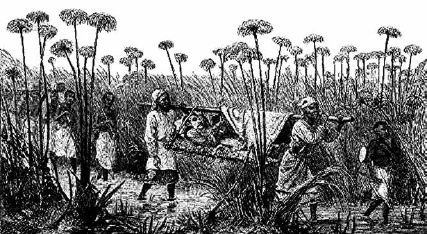

Dr. Livingstone and porters crossing a papyrus swamp.

His goal was to examine the drainage of a chain of lakes that included Lakes Malawi, Mweru, and Bangweulu (Maps 5 and 8, pp. 141 and 213), all three of which he described for the first time. They were considered important pieces in the puzzle. Unluckily, the southern ends of the last two lakes are located in excessively swampy places, places where papyrus swamps abound. In the case of Lake Bangweulu, the papyrus swamp is even larger than the lake itself. Livingstone’s worst moments seem to be his passage through these swamps, which like many things in Africa by his reckoning were always “inviting mischief.” Also, he never seems to have mastered the art of walking in a papyrus swamp. As he records on 26 September, 1867, “Two and a half hours brought us to the large river we saw yesterday; it is more than a mile wide and full of papyrus and other aquatic plants and very difficult to ford, as the papyrus roots are hard to the bare feet, and we often plunged into holes up to the waist.”

Then suddenly his reports stopped arriving in London and it was feared he had taken ill or worse. An American newspaper, the New York Herald, offered the services of Henry Stanley, by then a well-known explorer with firsthand knowledge of Africa. He rose to the challenge and found Livingstone alive, but grown old and weakened by fever, dysentery, and poor diet.

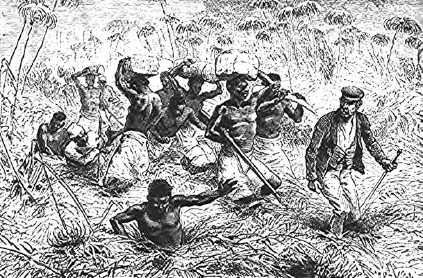

After their momentous meeting in Ujiji in 1871, Stanley stayed on for four months while Livingstone recovered, and together they explored the rivers and lakes of the region. They were especially interested in the Ruzizi, a papyrus-lined river that connects Lake Kivu to Lake Tanganyika (Map 5, p. 141). Several explorers before them had said or suggested that Lake Tanganyika drained into Lake Kivu by way of this river. The assumption was that Lake Kivu then drained into Lakes Edward and Albert, and from there into the Albert Nile. If true, it meant that Lake Tanganyika (the longest lake in the world and one of the deepest, second only to Lake Baikal in Siberia) was merely an extension of the Nile! All that was needed to confirm this was to witness the northerly direction of flow of the Ruzizi. But the minute Livingstone and Stanley arrived on the river, it was obvious to them that it flowed south, indicating that Lakes Kivu and Tanganyika were part of the Congo drainage system (Map 5, p. 141). This incident accounted for the famous picture of Stanley and Livingstone leaning together over the gunwale of their boat as they closely examined the water of the Ruzizi (p. 216), a scene that in one form or another made the front pages in many of the world’s newspapers in the 1870s. Coincidentally, it provided the world with its first great view of what papyrus swamps really look like. The tall stems, graceful umbels, abundant birdlife—it was all there, and it showed this illustrious pair as if they were drifting through a swamp in ancient times. All that was lacking was a set of royal throw-sticks and a pharaoh or some other noble to show them how to really take advantage of a papyrus swamp.

In his diary, Livingstone chafed at the way other explorers made hasty decisions, too often based on little information. He singled out as an example a statement by Samuel Baker—our Sam—who said that “Every drop from the passing shower to the roaring mountain torrent must fall into Albert Lake, a giant at its birth.” This attitude of Baker and his smug certainty that Lake Albert was so important as a catch basin brought from the good doctor the comment: “How soothing to be positive.” Yet until his death Livingstone himself was convinced that the Lualaba River was the ultimate headwater of the Nile. In fact, it was subsequently shown to be the source of the Congo (Map 5, p. 141), but by then it mattered little as Livingstone was resting peacefully in Westminster Cathedral.

Livingstone and Stanley in a papyrus swamp at the mouth of the Ruzizi River, 1871.

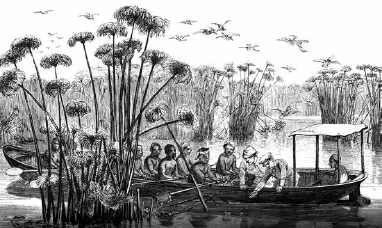

Once replenished by supplies from Stanley, Livingstone went on his way and Stanley returned to the coast. Livingstone’s last trek took him in the direction of the swamps of Lake Bangweulu, a course that some say led to his death. Deeper and deeper he waded into this world of water.

March 1873—It is impossible to describe the amount of water near the Lake. Rivulets without number. They are so deep as to damp all ardour. . . . The water on the plain is four, five, and seven feet deep. There are rushes, ferns, papyrus, and two lotuses, in abundance. . . . The water in the country is prodigiously large: plains extending further than the eye can reach have four or five feet of clear water, and the Lake and adjacent lands for twenty or thirty miles are level. . . . The amount of water spread out over the country constantly excites my wonder; it is prodigious. . . . (Dr. David Livingstone, 1874, The Last Journals.)

Horace Waller, the compiler of Livingstone’s journals, commented in 1874: “As we have said, a man of less endurance in all probability would have perished in the first week of the terrible approach to the Lake. . . . It tried every constitution, saturated every man with fever poison. . . .” Soon enough it caught up with this frail, gray-haired, emaciated old hero. Exhausted, unsteady on his feet, litter-bound and fever-stricken, he died in May 1873 at Chitambo. His heart was buried in Africa and his mummified body sent home for a state funeral. He died as he lived, constantly moving on to new and exciting adventures. The Ancient Egyptians would perhaps say that he had already reached Heaven, as he had died inside a papyrus swamp—a Field of Reeds.

Livingstone close to death inside a papyrus swamp.