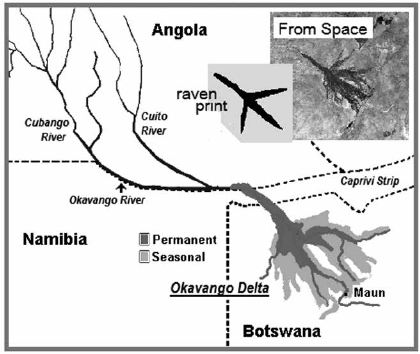

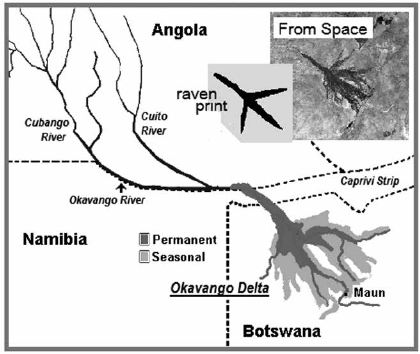

MAP 9: The Okavango Delta (based on NASA, FAO Aquastat 2005, and OKACOM).

The Okavango, Miracle of the Kalahari

What does a papyrus swamp look like from space? We know of one—the Okavango Swamp in Botswana—that looks like a giant print of a bird’s foot. Papyrus grows along the major channels that cut through the swamp; these channels lined with papyrus are distinctly seen in satellite images in contrast to the arid terrain of the Kalahari Desert, which surrounds the swamp. Gradually the watercourses peter out at the “toenails” as they grade into the reed-choked wetlands that make up much of the Okavango seasonal swamps. Since the watercourses radiate out from an apex, the effect is that of looking at a green footprint left by an enormous six-toed bird (Map 9, p. 231).

Why such an unusual topography? Is there any significance in the outline, like the lines the Nazca Indians in South America cut into the face of rock formations, which depict earthly and mystic shapes, designs difficult to see unless you are a great distance above the earth, presumably because this is the way the gods see them? Or is it an extraterrestrial reaffirmation of the international symbol for peace—a sign made up of the semaphores for N and D (possibly standing for nuclear disarmament?) and coincidently the Celtic symbol for peace, which happens to be a circle with the imprint of a chicken or raven’s foot inside?1

MAP 9: The Okavango Delta (based on NASA, FAO Aquastat 2005, and OKACOM).

Mystical musings aside, in the case of the Okavango there is no mystery. The toes are splayed out along two fault lines, geologic features common to the rift system that extends from the eastern Rift Valley into this part of Botswana. As in the case of the northern geological rift where the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden join the Great Rift Valley, many millions of years from now this part of Botswana that lies between the faults will be split apart as the continent divides. Meanwhile it is geologically a very active area that is slowly sinking.

The Okavango River originates in the tropical highlands of Angola. From there it flows southward through parts of Namibia on its way into the Kalahari, where it ends in a large alluvial fan referred to as the Okavango Delta. Water flows into the region because of the gently sloped, slowly sinking terrain, but as it flows across the delta it disappears because it evaporates or is soaked up by the substrate. Since little or no water leaves the system, it is referred to as an “inland” delta. Kennedy Warne, co-founder and editor of New Zealand Geographic magazine, described the flood as a miracle that “. . . happens in slow motion . . . this part of southern Africa is so flat that the floodwaters take three months to reach the delta and four more to traverse its 150-mile length. Yet by the time its force is spent, the flood has increased the Okavango’s wetland area by two or three times, creating an oasis up to half the size of Lake Erie at the edge of the Kalahari Desert.”

Almost 6,100 square miles in size and covered by seasonally flooded grassland and permanent papyrus swamps, the Okavango Delta is about as large as the Everglades, and similar to other deltas in that the river disgorges onto a delta plain that is roughly triangular in outline, but there the similarity ends. The Okavango Delta is unusual in many ways; not only does the water not flow into the sea and evaporates into thin air, but when the floodwater arrives it noticeably lacks suspended mud, the one quality common to so many tropical rivers. As a result there is no layer of alluvium as in other deltas, such as the Nile before the Aswan Dam. Since there is no mud deposited, there are also no levees or bars built up, as on the Mississippi, and the soils are not the fabled black fertile stuff that made Egypt a world power in ancient times—instead, they are a weak slurry of sand and organic matter. In the Okavango Delta there are hundreds of islands composed of this sand and organic material that support shrubs and trees.

Land subsidence within this delta happens more rapidly in some places than others, and it is to such places that the water flows and helps produce a soil with the aid of tree roots. Thus we have dust and sand from the Kalahari mixed with deposits induced by the aquatic vegetation as a basic soil generated within the system. This is mixed with organic matter derived from termite mounds, which rise above the level of the floodplain. As a result, the delta somehow keeps pace with the sinking terrain. The soils produced, however, are not very fertile, and throughout much of the delta there are few areas suitable for large-scale commercial irrigation.

Prof. Terence McCarthy, from the School of Geosciences at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, has carried out numerous studies of the Okavango Delta that describe this process of salt-trapping by trees and the soil-building activity of the termites. The combined effort of trees and termites keeps the water in the swamps fresh and helps expand the islands. In addition, papyrus grows aggressively across the channels and in the process produces peat that is recycled by the local fauna and flora. According to Prof. McCarthy, this compensates for the subsidence so that the delta remains an alluvial fan of remarkably uniform gradient.

This also means that there was never a scramble to stake out claims on fertile land. Nature was left in control. Niles Eldredge, the famed paleontologist and curator and chairman of the Department of Invertebrates at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, points out that the Okavango is today the closest thing remaining on earth to a true Eden, the place where the story of mankind began, a place of primordial settled existence where the game was as thick then as it is today.

In his book Life in the Balance, Dr. Eldredge gives us a great description of what it feels like on first entering the Okavango swamps. “For one thing, in the eastern reaches at least, the main watercourses are lined with tall reeds, peppered with small stands of papyrus. Even standing in the boat, you cannot see beyond the thick wall of grasses and papyrus, except in places where the watercourse widens, or where there has been a recent fire. As you go northward, the papyrus increases in frequency, until it is the dominant and, ultimately, the only plant lining the waterways. This plant, with its long, tough green stem and frizzy top knot, has given us the very word ‘paper’.”

A host of indigenous and migratory birds make the delta their home. More than 500 species live there, including the African fish eagle, flamingoes, sacred ibis, and the slatey egret, a threatened species that breeds here. Many species of fish thrive in the water, like tiger fish, sharp-toothed catfish, barbel, and bream.

The Okavango is also a place where salt taken out by trees is left behind in brine pools and salt crusts. The combination of fresh water and salt acts as a powerful magnet during the dry season as large herds of elephant, buffalo, and thousands of antelope looking for forage arrive in the swamps, and they in turn attract predators such as the unusual lions here that have learned to swim from island to island.

The marsh-dwelling antelopes found here include the lechwe (Kobus leche), an animal similar to but larger than the sitatunga. Like the sitatunga, they do not do well on dry land, and so keep on the move following seasonal changes in the swamps. Their legs are covered in a water-repelling substance that allows them to run quite fast in knee-deep water. Unlike the sitatunga, the lechwe have smaller hooves and are not confined to papyrus swamps; they can take advantage of other types of swamps, where they are regularly seen grazing shoulder-deep in the water.

The fauna and flora of the Okavango have become a prime tourist attraction. The result, as pointed out by Warne in his 2004 article in National Geographic, is that “Botswana has strong economic as well as political reasons for wanting to keep the delta pristine: Okavango tourism is second only to diamond mining as a foreign-exchange earner. The delta is a golden egg, but Botswana neither feeds nor owns the goose.”

He is referring to the fact that the Okavango River originates in Angola and passes through Namibia before arriving in the delta. In Botswana the river feeds the swamp habitat and supports the abundant and exotic bird life along with elephants, lions, hippos, and crocodiles. Botswana sees it as an important asset to biodiversity; Namibia and Angola see it as water. Since water can be equated with development and progress, it is hard for Namibia and Angola to resist using that water to irrigate fields and provide for domestic needs, no matter what happens to the animals and plants downstream.

The Okavango wetlands, like those of so many other areas in Africa, now stand in danger because of water diversion. Apparently they must suffer, but the questions are by how much and in what ways. Immediately threatened is the basis of a large tourist industry. In 1997 it was declared one of the world’s two largest Ramsar sites (the other is the Sudd in Southern Sudan). Also about that time, Namibia announced plans to pipe water from the incoming Okavango River to its capital city, Windhoek, and other central regions. Plans were also forthcoming from Angola and Botswana.

River inflow during the November–April rainy season brings to the delta 353 billion cubic feet of water that disappears into the sand or is lost to evaporation. All three countries have needs that depend on the same water from the same river. Of these, Botswana itself has the most ambitious plans, including dredging and building levees to increase and regularize flows and create reservoirs, as well as various canals and pipelines. All are intended to improve livestock management, provide for water supplies, and commercial irrigation, along with supplying water for a nearby diamond mine.

The potentially adverse effects of such plans are under consideration by the tripartite Okavango River Basin Commission (OKACOM), established in the mid-1990s with Angola, Botswana, and Namibia as members. Officially, they meet once a year and affirm that government officials have an interest and a willingness to collaborate with district and village councils on a range of small-scale projects. This allows the water users in the basin to move away from a model of strict water rights to one of basin-wide “benefit-sharing.” Most recently the group discussed creating a trans-frontier wildlife park for tourists, along with other methods of sharing tourist-related revenue. The discussion on the Okavango encourages conventional water projects as well as alternative projects that use surface and groundwater for sustainable development, such as communal ranching, wildlife management, and ecotourism.

Does all this sound like a water war? Not really. The discussions are, thankfully, not full of the angry statements so common to the Nile Basin talks. In an interview with Anthony Turton, a specialist consultant on water, energy, and socio-economic development in southern Africa, on the subject of a pipeline that Namibia hopes to build to divert water from the Okavango River, Turton said that Namibia needs the water to promote development and give its country greater water security. He also reiterated that the pattern of water flow through the Okavango is well understood. “The river experiences two infusions, or pulses, every year and the engineers know that water cannot be taken from the river before these pulses have been allowed to progress through the length of the water course.

“The Okavango is misquoted,” he continued, “as being a river in conflict. . . . There is a river basin commission that is functioning extremely well, but for the uninformed person, they tend to misinterpret the posturing of the different commissioners who make certain statements, without understanding the underlying dynamics. There is a high level of cooperation in that river basin.”

It is uncanny how like Egypt Botswana is. Lying as it does inside a desert, it depends on 94% of its water coming from outside, compared to Egypt’s dependency of 97%. Both have large deltas, both import a great deal of their food, and both depend on industry (diamond mines in Botswana and oil and gas in Egypt) and tourism for their foreign exchange. The largest difference is the lack of silt that in ancient times made Egypt a world power with standing armies supported by the food production that came from the silt. In the Okavango Basin, according to a 2006 benchmark paper by Prof. Donald Kgathi et al. from the Okavango Research Institute, there is not much erosion from the Angolan Highlands; the natural vegetation composed of shrubs, grass, and trees has been preserved. This happens because of the low population density in the region, in turn due to the widespread occurrence of tsetse fly (Glossina spp). Also, the basin is situated far from heavily populated areas. The water in the river is thus relatively pristine, though phosphates are beginning to rise as more farmers turn to chemical fertilizers to help the impoverished soil.

Without nutrients or silt coming in, how then does the wetland vegetation survive? Keith Thompson, my former colleague in Uganda whom you met in the beginning of this book, felt that the Okavango Swamp already contains the chemical elements that the swamp needs to survive. Nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus largely contained within the plants themselves are recycled into the peat. In fact, the papyrus that thrives at the apex of the Okavango Delta enjoys a high growth rate because the microbes associated with it can fix more than enough nitrogen for its needs. The same plants also trap what little nutrients or silt might come along. In the future, when land in the Angolan Highlands comes under cultivation and the silt in the river rises along with higher phosphorus content, the Okavango papyrus mats will act as a buffer.

Up to a point this is good, but as Warne points out, the managers, safari guides, and boatmen who work the swamps every day are appalled at the way papyrus responds to the increases in phosphorus. What they see is the unbelievable expansion of growth that we saw in the Lake Victoria swamps when sewage is passed into the papyrus swamps. This increase in phosphorus allows papyrus to spread out over channels at the head of the swamp, thus blocking paths previously cleared and making it more difficult to get around in the swamp. In the past, hippos cleared these channels, but with the increase in tourist traffic and decline in hippo numbers, channel clearance now becomes an ongoing problem.

Unlike the delta in Egypt, the wetlands of the Okavango were never cleared, although the margins were farmed for thousands of years. The farmers confined themselves to the seasonally flooded grasslands called “molapo” along the edges of the delta. The molapo were cultivated and cattle grazed on them using methods of traditional subsistence farming that are still common along the western and southeastern fringes of the delta. This kind of farming is risky, since the extent of the flood varies considerably each year and the farming effort must be coordinated to coincide with the start of flood recession and the start of the rainy season. If the fields are not flooded and kept watered, only meager yields can be expected.

Still, this is the kind of low-impact, low-investment farming system that should be encouraged and improved on, perhaps with the aid of small-scale irrigation using modern water-saving methods. As Prof. Kgathi says, “While conservation of the natural environment is critical, the pressing development needs must be recognized. The reduction of poverty within the basin should be addressed in order to alleviate adverse effects on the environment.”

Improved molapo-type farming could help, but is instead in decline because of the attractions of urban life and the quick money to be made from the tourism sector. For example, Prof. Kgathi noted that 60% of the people in the delta are engaged in some form of services or work that relates to tourism, but it is often conventional high-end tourism: big-game hunting, fishing excursions, and up-market photographic safaris—the kind of tourism that pulls in millions in foreign exchange but generally fails to promote rural development because it marginalizes the poor. The best kind of eco-tourism that would conserve wetlands must be the kind tied to programs and projects like the Green Zone Cooperatives in Mozambique or the Campfire Program in Zimbabwe. The Campfire Program ensures local participation in decision making and sharing of all revenues earned through the program by producer communities. It fully subscribes to the axiom that no development program can succeed in rural or communal areas if it disregards the beliefs and attitudes held by the people it is intended to benefit.2

Of the 125,000 or so people affected, about half live in the Maun region, the urban center in the southeast. The others live on the margins of the seasonal wetlands, where they make use of the wildlife, fish, papyrus, reeds, thatching grass, trees, veldt products (tubers, etc.), small-scale cattle ranching, and molapo cultivation. They sound very much like modern-day counterparts of the ancient marsh men of Egypt.

The Okavango sits a continent apart from the Nile, yet the impression is inescapable that here is what the Nile Delta might have looked like 6,000 years ago. As Dr. Eldredge noted, it is an Eden preserved with its multitude of game animals and birds. It is also a place where marsh men pole boatloads of tourists along channels that are lined with walls of green, like the royal bird hunters of old plying the papyrus swamps in which the sacred sedge towered over all.

In ancient times, the 1,100,000 acres of papyrus swamps of the Nile Delta provided a vast natural resource that generated millions of dollars; today the 300,000 acres of papyrus in the Okavango adds a fascinating twist to the other famous attractions in Botswana, all of which have created a tourist haven. The income from tourism in 2010, according to the government of Botswana, was estimated to be $1.3 billion and to generate 54,000 jobs—small in comparison to the income from diamonds, but important for diversification. Botswana now ranks 42nd in the world in terms of long-term growth expected in the tourism sector, much of it due to the Okavango River and the swamps.

Through the years, thousands of studies have been conducted of the Okavango, and numerous seminars and conferences have been held. The Okavango Research Institute (ORI), located in Maun, a constituent part of the University of Botswana, is a marvel at coordinating this research. One of their undertakings is a joint project with the Kalahari Conservation Society and the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN)—the Biokavango Project, which will build local capacity for sustainable use and help the tourism sector to directly contribute to sustainable small-scale, multi-use rural development (including fisheries, agriculture, and hunting). This interest in community-based natural resource management and ecotourism—that is, “tourism that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people”—is more in line with what is needed.

If Botswana succeeds in involving the entire community in sustaining their own lives as well as the biodiversity of the Okavango Swamp, and does this in the context of shared resources with neighboring countries, it will set a great example by providing a much-needed model for the development of the Sudd as well as for the Nile Delta, and perhaps other river basins in Africa like the Zambezi and the Congo.