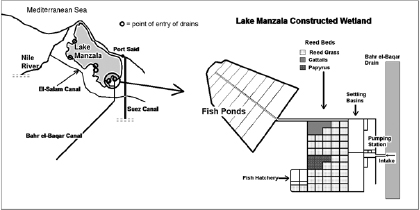

Lake Manzala Constructed Wetlands Program (after El-Din El-Quosy, 2007).

Due to the camera angle, it looked like Prof. Dia El-Quosy was standing on water.1 To the many graduate students and technicians trained by him, this would come as no surprise. He had been with the Lake Manzala Engineered Wetlands Project from its beginning in the ’90s and he was highly regarded as the doyen of engineered wetlands in Egypt. If he could tackle the most polluted site in Egypt, armed only with some native plants, walking on water would be easy.

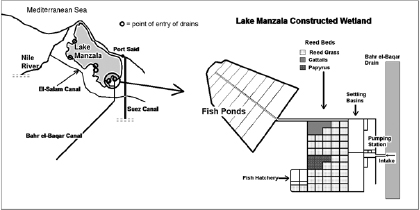

In addition to being project manager, El-Quosy is also Professor Emeritus at the National Water Research Center. He looks a lot like a very serious version of Richard Gere, with his light-gray, wavy hair and clear, windowpane-type eyeglasses. He was explaining to a small audience how the project worked. The wastewater that feeds into the wetland is taken from the infamous Bahr El-Baqar drain near Port Said and pumped into ponds where sediments are allowed to settle. Then the water flows through 60 acres of reed beds. After leaving the reed beds, the water flows into fish ponds and then into Lake Manzala, the largest of the Four Sisters in the northernmost end of the delta.

The project was in full swing by October 2004, and the world of water purification was interested because this was the first major undertaking of this type in Egypt. There had been other engineered wetlands operating in the delta, but nothing like this. People were impressed. Locally, the fishermen had almost given up hope. For thirty years heavy metals have been carried to the delta muds by way of agricultural and industrial drains. They came originally from the effluent of power-based industries that sprang up with the advent of the Aswan High Dam. To make matters worse, a significant portion of the water in the Nile River that used to dilute the incoming wastewater in the lake was diverted in 1997 into the Al-Salam Canal. That canal passes under the Suez Canal and from there goes into the Sinai, where it is used for irrigation.

In addition to the toxic effect of heavy metals, the wastewater entering Lake Manzala contains raw sewage and wastes from agricultural and industrial processing. A 1994 assessment pointed out that many Egyptians could identify fish in the marketplace taken from the lake because of the prevalence of gill diseases, internal parasites, and the unmistakable smell that gave them away. They were afraid to eat them.

In response to these concerns, the idea was broached of a filter swamp in the delta, and a UNDP-funded project was begun under El-Quosy. It eventually cost $12 million but was considered well worth it. The success of the project is due to the cleansing action performed by the reed grass (Phragmites), a plant that is well able to withstand the more concentrated effluents of the Bahr El-Baqar drain, the most notorious source of pollution in Egypt.

Cattail (Typha) and papyrus were also included in the Lake Manzala project, but neither did well because the wastewater from the Bahr El-Baqar is quite saline. All the same, it is amazing the way papyrus keeps showing up in newly constructed wetlands. It has been featured in a small wetland built in Ismailia on the west bank of the Suez Canal, and it is the plant of choice in several filter swamp schemes in Uganda, Tanzania (Zanzibar), Kenya, Ethiopia, Cameroon, and even Thailand. It’s almost as if designers of filter wetlands and the general public want the plant to come back and populate the delta immediately, but it will require more time for papyrus to adapt and propagate itself under these new conditions. It would probably do better in constructed wetlands closer to Cairo, where the wastewater is not as salty. The Bahr El-Baqar Drain, for example, increases in salinity by over 100% over its complete length (71 miles from Cairo to Lake Manzala).

Lake Manzala Constructed Wetlands Program (after El-Din El-Quosy, 2007).

Both the reed grass and cattail are better adapted for saline wastewater, but both are also notorious because of their aggressive and dense growth. They are considered weeds in many places in the world, and it is often recommended by wetland managers that stands of both species be diversified with swamp plants that are more useful as waterfowl food, such as wild millet, smartweeds, rice cutgrass, and wild rice. Outside the delta, in oxidation ponds in the New Valley in the Toshka Project region, Prof. Safwat of the University of Minia is trying out cattail and reed grass species that will bear the brunt of highly saline and toxic wastewater in that region.

Papyrus, on the other hand, although it does not do well in saline waters, is valued for its ability to provide the habitats and niches loved by fish (who will be healthier in this cleaner water) and wading birds. Its capacity to grow in floating mats is also useful in systems where wastewater must pass under the mats and be filtered and cleansed in the process.

After one pass through the reed beds in El-Quosy’s project, the water is more oxygenated, has 80% less suspended solids, fewer coliforms, and lower phosphorus, nitrogen, and heavy metal content. As expected, maintenance costs are low, and local livestock handlers harvest the reeds for feed at no cost. It was initially designed to treat 6 million gallons of wastewater per day but is now capable of twice that. As a result, Egypt has a model of how filter swamps could work and how they could help the nation cope. The project is also an important turning point for the rest of Africa, since this is a mirror image of what could be done in many of the other countries of the Nile Basin.

The sequence is clear. Any increase in agriculture that demands more water means that land must be cleared, wetlands must be drained, and hydroelectric power must be developed to provide the energy for fertilizer and industrial development. The resultant pollution is made worse by an increasingly arid environment and reaches a critical point from whence the population suffers.

In other words, they are digging the hole in which they will be buried. How to get out of it? The ladder is provided by a reformed government, with rungs generated by water and soil conservation, renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and wetlands to cleanse and recycle water.

In a passionate address to the world and especially to his fellow Egyptians, Dr. Hassanein earlier pleaded for the environment to be made a national priority. His immediate goal is to stop the Nile River from becoming a serious hazard to people, and to stop and reverse the present trend of environmental deterioration in Egypt, as well as to help the government enforce the law, and business and industry to minimize the impact on the environment. The goal he had in mind was to save Egypt from the coming environmental tragedy that will materialize if the country stays on its present course. Included in his challenge is the caution to aim for a sustainable future, which would mean turning a receptive ear to the idea that Egypt, as in ancient times, can survive and prosper on the natural resource base that they already have, provided that it is managed in a sustainable way. The water already in the system and that expected from a newly managed Blue Nile will suffice, once it is efficiently recycled and cleansed.

The use of constructed or managed wetlands as filters for wastewater has now caught on in Africa as a practical solution to local sewage problems. Filter swamps come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Cost is a big factor in deciding which type to use. The cheapest is simply a large natural swamp into which wastewater is released. Often the wastewater is spread out to make the cleansing process more efficient. The papyrus swamps on Lake Victoria presently serve in this way.

The next most economical method is to dig out a maze of channels, canals, or ponds to create waste-stabilization ponds or reed fields in which wastewater is allowed to meander. The principle here is to prolong its passage in order to give the pond vegetation or reed beds more time to act. Construction costs are kept to a minimum because mostly hand labor is involved.

The most expensive filter swamps are the constructed wetlands, as in the Lake Manzala case where lined intake canals, pumping stations, and contained gravel beds are laid out and planted with reeds. The system is designed to handle a large regular flow of wastewater. As with solar power, there is an initial capital investment, but operational costs are modest, and the fact that wetland vegetation grows faster and year-round in the tropics makes such a system very attractive.2

The Egyptian working model demonstrated that such an approach can be used in the race to save the delta. As Global Climate Change takes its toll, wetland restoration seems the only feasible economic solution, since conventional sewage infrastructure is expensive and the task is enormous.

There is no question that the 60-acre facility at Lake Manzala is doing a great job, but five major wastewater drains enter the lake; the worst one of the lot, the Bahr el-Baqar, delivers 793 million gallons per day (3 mill m3/day), of which El-Quosy’s project can only handle a scant 2%. The consequence is that reports are still coming in that all four of the delta lakes are health hazards. But at least now the value of managed wetlands is appreciated, and it is heartening to see reports that Dr. Abdel-Shafy from the Egyptian National Research Center, who used papyrus and reed grass in an engineered wetland in Ismailia, will be conducting workshops and master classes in constructed wetlands directed at water technicians.

There are other conservation efforts in the delta where protected areas have been designated. Lake Burullos has been declared a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance, and the Ashtum El Gamil Protected Area has been created by Prime Ministerial Decree in 1988. This encompasses an area of almost 9,000 acres on Lake Manzala along the sandbar at Bughaz El Gamil near Port Said, the most important connection between the lake and the sea.

Expanding engineered wetlands in the delta will demand that the government take back land already designated for industry and housing. Perhaps wetlands in the future could be expanded by making them part of the national parks in Egypt. According to the National Plan for the Conservation of Biological Diversity, prior to 2017 Egypt plans to increase its 27 protected areas to 40, which will take up 17% of the Republic. Somewhere among those parcels of land, 3,000–4,000 acres of constructed wetlands might be found to rehabilitate the delta.

Prof. El-Quosy told me that his goal is to have 2,000–5,000 acres of reed beds or sedimentation ponds set aside along the coast to resolve the immediate needs of Lake Manzala. He would also like to see many small constructed reed beds on the desert side of all villages and towns in Egypt in order to promote sewage treatment and desert reclamation. This would greatly reduce pollution in the Nile and would encourage small-scale local cultivation of deserts in preference to the unwieldy, inefficient megaschemes favored by past governments.

Where does papyrus fit in? It will be a while before it shows up as a major component in managed wetlands along the coast. This is not for want of a ready market; there is already a demand for it in Cairo and Luxor in the souvenir trade, where cultivated papyrus stems are used to make specialty paper products, calendars, notebooks, etc., as well as finished, framed sheets of paper decorated with colorful hieroglyphics. Papyrus plantations are also popular at theme parks such as the Pharaonic Village that opened in Cairo in 1985. The Village was set up on an island in the Nile that is effectively hidden from the modern downtown skyline with screening trees. It quickly became an Egyptian version of Colonial Williamsburg in that it re-creates ancient times and crafts. Once inside the Village, tourists are taken by barge along papyrus-lined canals to see historic scenes and tableaux acted out by people dressed in period costume, and to marvel at the birdlife attracted back into the urban landscape by the new papyrus swamps.

It was originally set up by Hassan Ragab, the man who brought cuttings of papyrus back to Egypt to start up the souvenir paper industry. In addition to making and selling papyrus paper souvenirs, Ragab’s effort had a practical effect—it spawned a host of other papyrus paper factories and institutes that fed into the national effort to keep Egypt among the Top Ten World Travel Destinations. In the recent past, nine million tourists annually generated $7 billion in income, which had enough impact on the government that a plan was advanced to create new job opportunities for many Egyptians.

Tourism, which rose to 14.7 million in 2010, has taken a nosedive after the turmoil of the Arab Spring, but the general feeling is that it will come back, and when it does its future looks as bright and prosperous as ever—and it is a future in which papyrus can pull its weight.

As for the plant itself, it will never again grow as luxuriantly as it did in the swamps of old because the river water has changed. Today the mineral, nutrient, and pollution content are different. This may change with time, but for now papyrus remains a novelty in the land where it once ruled.

Dr. El-Hadidi from Cairo University found a relict population of papyrus growing amongst marsh plants in Wadi Natroum in 1971, and Dr. Serag at Mansoura University discovered a small natural stand in the delta in 2003. Cuttings replanted in a plot in the Nile Delta near Damietta did surprisingly well in Nile water, perhaps because a continuous flow flushed the site, enabling it to survive. But even so, the production of both the cultivated and natural plant is much less than that found in the swamps of Central Africa.

It would help to have papyrus demonstration sites in Cairo, where urban-bound families and the Green Generation would be able to see wetlands in action. Small plots, experimental swamps planted in reed grasses and papyrus, could be featured in places like Al-Azhar Park in Cairo, the Giza Zoo, and private parks such as the Pharaonic Village. Such places would be appreciated by schoolchildren, Cairenes in general, and the new Green Army of the Nile, the ten million Egyptians whom Dr. Hassanein said must be reached through media and educational programs in order to increase environmental awareness and make the environmental vision a reality.

When I read Dr. Hassanein’s plea, I realized that one of his goals may already have been reached, since the number of Internet sites and organizations dealing with green issues and the environment in Egypt has grown that much over the past few years. On the Internet today there are also advocacy groups promoting sustainability and environmental protection throughout the Middle East. Future steps will be needed to develop incentives, awards, and assistance programs to reduce pollution and help the nation become more environmentally friendly. In this it helps to promote programs that would protect biodiversity, and obviously those that include protecting the avifauna en route to and from Sudan and Egypt and ecosystems such as the delta wetlands and the Sudd that provide the habitats that allow birds to survive.

With time and experience, Egypt could become a major player in the field of filter swamps, and a source of hope and encouragement for all of Africa.