7

Bantam Ben and Slammin’ Sam

During the final decade of the nineteenth century, Charles Blair Macdonald fancied himself a pretty good golfer. Although an American by birth, Macdonald had learned the game while studying in Scotland, going so far as to play matches against Young Tom Morris.

Since no golf courses existed in the United States in the 1880s, Macdonald was forced to set his sticks aside. But as the game began to take hold, Macdonald mobilized some buddies and constructed what came to be known as the Chicago Golf Club, the first actual course west of the Alleghenies. In the process, Macdonald established a new American profession, golf course architect, with himself as the guru.

He was, to an extent, stealing from across the sea. Old Tom Morris had been designing golf courses in Scotland and England for decades, and Morris wasn’t alone. In the United States, however, the nascent activity was far more rudimentary and haphazard. What Macdonald did was formalize the process, introducing deliberate planning to the design of holes. That “planned” concept saw its first full flower in the United States in 1909 when Macdonald opened the National Golf Links of America on eastern Long Island.

At National, Macdonald’s architectural hand could be seen in many of the eighteen holes, which he manipulated around and through sandy coastal land. He designed the par-five seventh and par-three thirteenth holes as replicas and homages to the famed seventeenth and eleventh, respectively, at St. Andrews in Scotland, where he had faced Young Tom. Other holes at National mimicked memorable holes at Royal St. George’s, Prestwick, and other popular British-Scottish courses of the day.

Probably more than any other American course, Macdonald’s success at National spurred an industry. His collaboration with Seth Raynor led to the Old White at the Greenbrier, the Yale University course, and Mid-Ocean on the island of Bermuda. It also spurred competition. At Pinehurst in North Carolina, club pro Donald Ross, whose competitive efforts rarely won him more than a fifth-place finish (and a check for eighty dollars) at the 1903 U.S. Open moved into architecture. Ross designed four new courses for his home complex, the reception prompting him to take up the task full-time. He designed Oak Hill in Rochester, Seminole in Florida, and Inverness in Toledo, all of which remain respected today. In the early 1920s, Ross produced Oakland Hills outside Detroit, a layout that gained notoriety when it hosted the 1924 Open at a length of 6,880 yards, more than 300 yards longer than the previous record.

Over the ensuing two decades, golf course planning and design developed into an art. Macdonald died in 1939 and Ross in 1948, but by then A. W. Tillinghast had made his own name at Winged Foot and Alister Mackenzie had opened Cypress Point. In 1934 Mackenzie’s collaboration with Bobby Jones produced Augusta National.

The outbreak of World War II stunted course design, as it did other facets of the game, but only temporarily. With its end, Robert Trent Jones emerged to succeed Ross and Mackenzie as the game’s foremost designer. Trent Jones opened Peachtree with Bobby Jones in 1948 and the Dunes a year later.

The war had a similar “generational change” effect on the ranks of competitive players. With the exceptions of Sam Snead and Lloyd Mangrum, careers that had flourished before the war ended abruptly. Ralph Guldahl and Byron Nelson both effectively retired. Craig Wood and Lawson Little dabbled seriously in a few of the major postwar events but found that they were no longer factors.

The tour ground along at a halfhearted pace during the war. Rationing of goods and services was one impediment; the loss of some top players to the service was another. Bobby Jones conducted the Masters in 1942 before suspending it, but the U.S. Open was not resumed until 1946.

With the war’s conclusion, players whose positions at the cusp of greatness had been slowed or derailed entirely by its arrival—notably Ben Hogan and Jimmy Demaret—marched to the game’s forefront. The postwar era also saw the advancement of the professional game across wider reaches of the globe, including Asia, Australia, and Africa. In short order, one man brought those regions into contact.

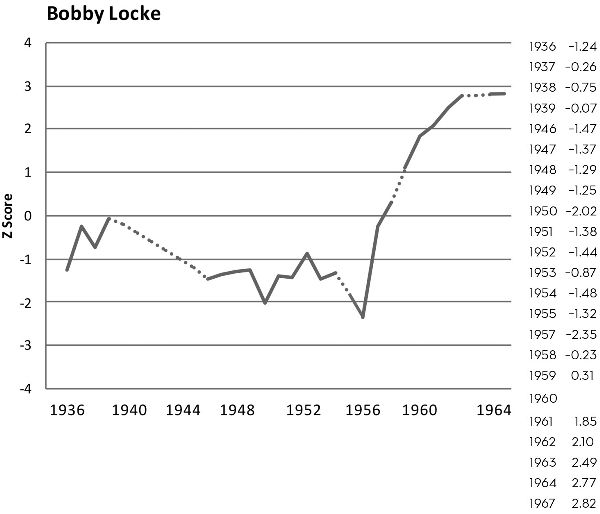

Bobby Locke

The first true world golfing figure traveled by the rather ungainly name of Arthur D’Arcy Locke. The awkward label proved fitting, for Bobby Locke was an awkward man. He emerged from the South African gold mines to become a player of note in prewar Britain, after the war taking his game to America and then the world. At various times, Locke held the national championships of nine countries on four continents.

On course, Locke was prickly to the point of being annoying. Fellow competitors disliked his personality almost as much as they admired his game, particularly his putting stroke. His professional churlishness may have stemmed from the fact that—as a native South African—he never played in a major competition anyplace near his home. Few appreciated his pace, which was glacial. The odd thing about Locke was that his on-course demeanor was a 180-degree departure from the ukulele-playing, devil-may-care off-course habitué of after-hours spots.

It was said that Locke honed his game as a boy in South Africa by reading Bobby Jones’s instructional books. His swing looked like something slapped together across paragraphs: it was wristy, forced, and strikingly inside out, not at all reminiscent of Jones’s own. But it worked in South Africa, enabling Locke at the tender age of thirteen to walk away with his homeland’s boy’s championship. By 1935, still just seventeen, he held the championships of both South Africa and Natal, along with each area’s amateur crowns. He reprised the Natal title in 1936 and the South African victory in 1937.

So great was the young Locke’s reputation that his employer, the Rand Mining House, shipped him off to its London office, where his light workload gave him time to mingle with an aging Harry Vardon. Locke debuted in the British Open in 1936, catching everybody’s attention with an eighth-place finish. Not yet twenty, he turned pro and tried again in the 1937 Open, tying for seventeenth. An established figure in Britain by the war’s onset, he played a few tournaments back home in 1940 before enlisting in his nation’s air force.

When the war ended, Locke moved to America to give the more lucrative U.S. tour a try. Due in part to his slow pace, he became less than a fully welcome figure. The hook produced by his severe inside-out swing plane—so consistent he was said to line up as much as 45 degrees off target just to account for the natural ball flight—also drew criticism. But the big problem was probably Locke’s performance: he was threateningly good. When the British Open resumed in 1946, Locke tied for second behind Sam Snead. In 1947 he tied for third at the U.S. Open. He finished fourth in that event in 1948 and again in 1949 and then returned to Britain to win a playoff with Irishman Harry Bradshaw for the 1949 Open title. This was the famous “battle with the bottle.” On the fifth hole of the second round, Bradshaw drove into the rough, the ball coming to rest amid shards of a broken beer bottle. Rather than seek free relief from the outside agency—which the rules would have allowed—Bradshaw chose to play the ball as it lay in the glass. He failed to move it very far, losing a stroke that would eventually prove decisive.

In one thirty-two-month span, Locke played in fifty-nine tournaments, winning eleven, finishing second ten times, third eight times, and fourth five times. He quickly gained a reputation as the sport’s best on the greens.

Spurred by his first major win, Locke remained in Britain to play most of the 1950 season, prompting the PGA to suspend him, allegedly for breaking appearance commitments. Locke thumbed his nose at the Americans by repeating his British Open victory that summer, this time by three strokes over Argentinean Roberto De Vicenzo. When the PGA relented in 1951, the South African deigned to come back on a pick-and-choose basis. He finished third to Hogan at the U.S. Open at Oakland Hills in 1951 but otherwise spent most of his time chasing trophies on the European and South African tours. In 1952 he returned for the first time in three years to the Masters, finishing twenty-first. Locke fared decidedly better in Scotland, winning his third British Open championship by a shot over Peter Thomson.

Locke stood out in his appearance and dress as well as in his play. At a time when brilliant golf attire was coming into vogue, Locke dressed almost exclusively in gray flannel knickers, white buckskin shoes, linen dress shirts with neckties, and white Hogan caps. His jowly features and changeless expression earned him the decidedly unflattering nickname of “Muffin Face.”

Locke used an old rusty-headed putter with a hickory shaft, addressing the ball at the toe and striking out at it. The result, as bizarre as it looked, was the same “hook” on the greens that had become his trademark off the tee. “Very early in my career I realized that putting was half the game of golf,” Locke said. “No matter how well I might play the long shots, if I couldn’t putt, I would never win.” It is to Locke that the aphorism “Drive for show and putt for dough” is ascribed. The putter rarely failed him, one of those occasions occurring in 1954. Locke came to the final hole of the British Open at Royal Birkdale needing to hole a birdie putt to tie Thomson. He left it just short and had to settle for second place.

After 1954 Locke largely confined his major appearances to the British Open, which he won for a fourth time in 1957. Although Locke’s play that week at St. Andrews was as solid as ever, fortune and a kindly rules official had something to do with the victory. Locke came to the final hole holding a three-shot lead, his second shot having stopped just a few feet from the cup. It lay, however, in the direct line of competitor Bruce Crampton’s putt. Locke marked his ball, moving the mark over the length of a putter head in order not to interfere with Crampton. But when he putted out, Locke failed to replace his mark in the proper spot. By rule that violation should have resulted in a penalty, which in turn should have resulted in Locke’s disqualification once he signed for the lower score. But tournament officials decided to waive the disqualification, finding in essence that no harm had been done.

This triumph, a few months before his fortieth birthday, combined with a serious 1959 car accident to mark the end of the most competitive portion of Locke’s career. Locke made largely ceremonial appearances at the British Open on and off through 1971, none of them noteworthy.

Locke in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1948 Masters |

T-10 |

291 |

–0.87 |

|

1948 U.S. Open |

4th |

282 |

–1.61 |

|

1948 Western Open |

3rd |

283 |

–1.40 |

|

T-4 |

289 |

–1.44 |

|

|

1949 British Open |

1st |

283 |

–1.69 |

|

1950 British Open |

1st |

279 |

–2.02 |

|

1951 U.S. Open |

3rd |

291 |

–1.69 |

|

1951 British Open |

T-6 |

293 |

–1.06 |

|

1952 Western Open |

2nd |

282 |

–1.45 |

|

1952 British Open |

1st |

287 |

–2.36 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.56. Effective stroke average: 69.68.

Locke’s Career Record (1936–67)

- Masters: 4 starts, 0 wins, –2.79

- U.S. Open: 6 starts, 0 wins, –8.43

- British Open: 15 starts, 4 wins (1949, 1950, 1952, 1957), –5.28

- PGA: 1 start, 0 wins, +0.71

- Western Open: 3 starts, 0 wins, –4.37

- Total (29 starts): –20.16

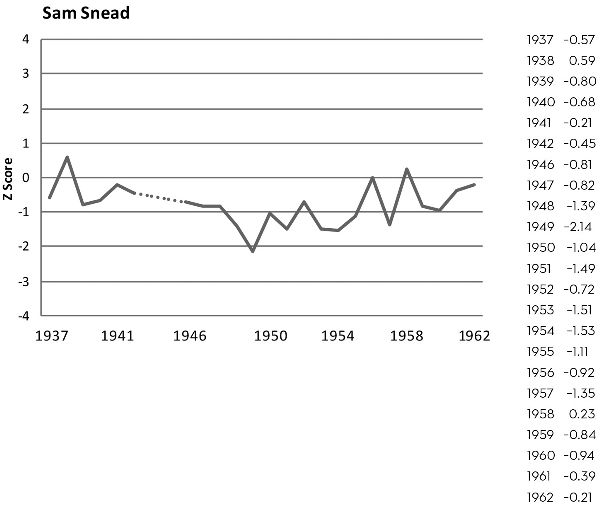

Sam Snead

Number 12 Peak, Number 4 Career

With Byron Nelson effectively retired, Lloyd Mangrum at war, and Ben Hogan yet to emerge as a front-rank player, Sam Snead was the face of the U.S. tour as peace resumed. Alone among the great prewar U.S. pros, Snead nurtured and enhanced his reputation into the latter part of the 1940s . . . and well beyond. The result was one of the most lengthy and productive careers in the history of American sport.

Snead emerged as a young pro out of Virginia in 1937 and made an immediate impact. The youngest of five children and a natural athlete, he ran a ten-flat one-hundred-yard dash in high school. He picked up golf watching his older brothers knocking balls around a cow pasture and took a liking to it. A job caddying at the nearby Homestead resort led to an assistant pro’s position at the equally tony Greenbrier across the state line in West Virginia. Snead studied golf mechanics hard but never allowed himself to get wrapped up in them. He was a “feel” player. “I try to feel oily,” he explained of his swing. At another time he said he knew he was hitting the ball well when “my mind is blank and my body is loose as a goose.”

Just twenty-four when he left Greenbrier to try his hand on the tour, Snead was an almost immediate success. In his first full season, 1937, he won the Oakland Open, the Bing Crosby Pro-Am, the St. Paul Open, the Nassau Open, and the Miami Open. Invited to play at the Masters, he turned in a score of 298 that put him in the top twenty. At the U.S. Open at Oakland Hills, the rookie posted a 283 that looked good enough to win and waited to see whether anybody could beat it. Ralph Guldahl did, playing the final eleven holes in 3 under par to consign Snead to runner-up honors.

Still, fans gravitated to Snead in the way they had gravitated to Bobby Jones nearly two decades earlier. “Watching him . . . provided an aesthetic delight,” said Herbert Warren Wind. “Here was that rarity, the long hitter who combined power with the delicate manners of shot-making, this slow-speaking, somewhat timid, somewhat cocky young man from the mountains.”1

He traveled to Britain with the Ryder Cup team and joined the American delegation at the 1937 British Open, tying for eleventh. Snead won eight more tour events in 1938, although he performed miserably in the majors. But following a second-place finish to Guldahl at the 1939 Masters, Snead entered that summer’s U.S. Open as a favorite and held the lead through seventy-one holes. He came to the final one needing just a par for the victory . . . but Snead did not know that. Thinking he needed a birdie, he gambled, made a triple bogey, and shot himself out of a three-way playoff.

Snead won six more times in 1941, and in 1942 he claimed the PGA Championship at match play. A handful of victories on the war-shortened tour followed, and then in 1946 Sam defeated Locke by four strokes in the British Open.

Snead did not return to that event for sixteen years, but the 1946 victory inaugurated what would prove to be his most extended stretch of golf superiority. Even that, however, could not bring him an Open victory. In 1947 he lost in a playoff to Lew Worsham.

Snead opened 1949 by winning the Masters by three strokes over Johnny Bulla and Lloyd Mangrum. In 1949 and 1950 Snead won sixteen tour events, including both Western Opens and the 1949 PGA. It is tempting to argue that more than any other player he benefited from the absence of Hogan, who had been sidelined by a near-fatal car crash in the spring of 1949. But the intimation that Snead could not hold his own against Hogan is plainly invalid. With Hogan’s return in 1950, the rivalry resumed, Snead winning the 1951 PGA and both the 1952 and the 1954 Masters. He defeated Hogan in the latter event by one stroke in a playoff.

In more than fifty years as an active competitor, Snead won a record eighty-two official tour events. He led the money list three times, won the Vardon Trophy four times, and played on seven Ryder Cup teams. His final tour victory came in 1965 when, at age fifty-three years and ten months, he beat the field at Greensboro. He was fourth in the PGA Championship at age sixty in 1972 and third in 1974 at age sixty-two.

For a player whose name will be forever attached to the phrase “didn’t win the Open,” Snead did remarkably well at that event, finishing as runner-up four times. Having said that, Snead’s true playground was Augusta National. Not only did he win the Masters three times, but he was also in the top five on four other occasions and beat the field average there seventeen consecutive times between 1939 and 1958. A three-time winner of the PGA at match play, Snead plainly excelled at the one-on-one game.

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1947 U.S. Open |

2nd |

282 |

–2.26 |

|

1948 PGA |

quarterfinals |

match play |

–2.16 |

|

1949 Masters |

1st |

282 |

–2.15 |

|

1949 U.S. Open |

T-2 |

287 |

–1.85 |

|

1949 PGA |

1st |

match play |

–2.08 |

|

1949 Western Open |

1st |

268 |

–2.47 |

|

1950 Masters |

3rd |

286 |

–1.85 |

|

1950 Western Open |

1st |

282 |

–1.95 |

|

1951 PGA |

1st |

match play |

–2.34 |

|

1951 Western Open |

3rd |

273 |

–1.62 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.07. Effective stroke average: 68.93.

Snead’s Career Record (1937–62)

- Masters: 23 starts, 3 wins (1949, 1952, 1954), –22.28

- U.S. Open: 22 starts, 0 wins, –17.92

- British Open: 3 starts, 1 win (1946), –3.56

- PGA: 22 starts, 3 wins (1942, 1949, 1951), –21.57

- Western Open: 12 starts, 2 wins (1949, 1950), –3.37

- Total (82 starts): –68.69

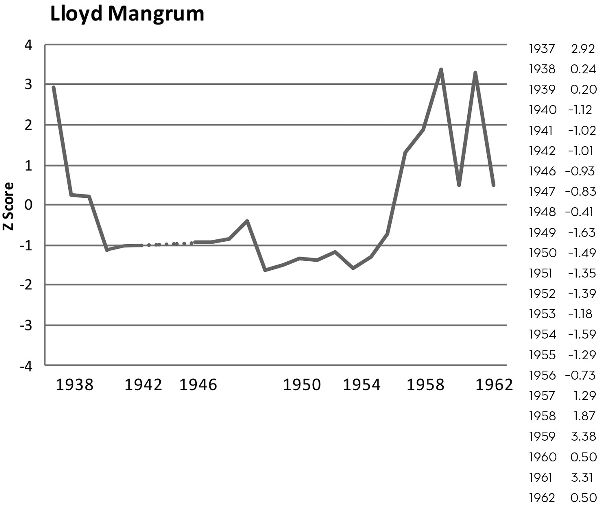

Lloyd Mangrum

Number 25 Career

Until Hogan’s postwar emergence, the most plausible figure to challenge Snead for supremacy on tour was a dapper, mustachioed man with a steady game. Another in a lengthy line of stars who came out of Texas—think Guldahl, Hogan, and Nelson—Lloyd Mangrum looked more like a leading man than an athlete. But he knew one and only one career path, starting as an assistant to his club pro brother at the age of fifteen and joining the tour at twenty-three.

Following a disheartening debut at the 1936 U.S. Open—he missed the cut—Mangrum picked up experience at minor events. He pushed Hogan to the limit at the 1939 Western Open, eventually losing by a stroke. Invited to the Masters in 1940, he finished second, four strokes behind Jimmy Demaret. He was fifth at the 1940 Open and a consistent top-ten figure from that point until the war intervened.

Mangrum felt its intervention more than most other first-rate athletes. An army sergeant, he saw action in Europe, including the Normandy invasion and the Battle of the Bulge. He acquired a broken arm during the former, shrapnel wounds in the latter. He returned home from the war in 1945 with four battle stars, two Purple Hearts, and no fear whatsoever of facing the tour’s biggest names. “I don’t suppose that any of the pro and amateur golfers who were combat soldiers, Marines or sailors will soon be able to think of a three-putt green as one of the really bad troubles in life,” Mangrum said.2

At thirty-two, Mangrum was entering a delayed but rich golfing prime. The 1946 U.S. Open, played at Canterbury Golf Club, east of Cleveland, loomed as a stage for Nelson or Hogan, the co–betting favorites. But when both stumbled down the final stretch, Nelson fell into a playoff with Mangrum and Vic Ghezzi, and Hogan fell out of it. That playoff turned into one of the most laborious and closely contested in major golf history, all three men shooting identical 72s to remain deadlocked after eighteen holes. Under the rules of the time, that forced them into a second eighteen-hole round the same afternoon. On the par-5 553-yard ninth hole—the twenty-seventh playoff hole—Mangrum drove out-of-bounds. But he recovered with a 60-foot putt for a bogey and then followed with three birdies in a four-hole stretch. Mangrum played the final two holes in bogey-bogey as rain and lightning poured from the sky, yet the three back-nine birdies provided just enough cushion. Mangrum won with a 72 to the 73s carded by Nelson and Ghezzi.

Between 1948 and 1950, Mangrum added sixteen tour victories, among them the 1948 Bing Crosby Pro-Am, All-American Open and World Championship of Golf, and the 1949 Los Angeles Open and All-American Open. He was the overlooked playoff loser in Hogan’s glorious return from his car-bus accident at the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion.

Mangrum finished third behind Hogan at the 1951 Masters, fourth behind Hogan at that summer’s Open, and fourth again at the Western Open. In the top ten at the Masters and Open in 1952, he routed the field at the 1952 Western Open, winning by eight strokes. In 1953 he was third at Augusta, third again at the U.S. Open, and second at the Western Open. The only trip of his career to the British Open that summer yielded his worst performance, a tie for twenty-fourth. In 1954 he was fourth at the Masters, third at the Open, and first at the Western. That gave him four thirds, two fourths, a sixth, and no finish outside the top ten in the Masters and Open alone between 1951 and 1954. Mangrum was the tour’s leading money winner and Vardon Trophy winner in 1951, repeating the Vardon award in 1953.

His health eventually did him in. A chain-smoker, Mangrum suffered the first of a series of heart attacks in the mid-1950s. Those attacks reduced his play to occasional appearances after his final victory, at the 1956 Los Angeles Open, and to none at all after 1962. The twelfth attack killed him in 1973. He was not yet sixty.

A grinder who built his reputation on playing in a lot of events and contending in most, Mangrum’s results are best illustrated by his performance in the Western Open. He entered all but one between 1938 and 1957, winning twice and finishing second three more times. Only the great Walter Hagen put together a better record at the Western.

Mangrum in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1949 Masters |

T-2 |

285 |

–1.77 |

|

1949 PGA |

T-3 |

match play |

–2.57 |

|

T-3 |

273 |

–1.79 |

|

|

1950 U.S. Open |

2nd |

287 |

–1.66 |

|

1950 PGA |

quarterfinals |

match play |

–2.07 |

|

1951 Masters |

T-3 |

286 |

–1.53 |

|

1952 Western Open |

1st |

274 |

–2.44 |

|

1953 Masters |

3rd |

282 |

–1.71 |

|

1953 U.S. Open |

3rd |

292 |

–1.57 |

|

1953 British Open |

T-24 |

301 |

+0.05 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.71. Effective stroke average: 69.46.

Mangrum’s Career Record (1937–62)

- Masters: 19 starts, 0 wins, –4.86

- U.S. Open: 16 starts, 1 win (1946), –3.14

- British Open: 1 start, 0 wins, +0.05

- PGA: 9 starts, 0 wins, –8.98

- Western Open: 16 starts, 2 wins (1952, 1954), –17.56

- Total (61 starts): –34.49

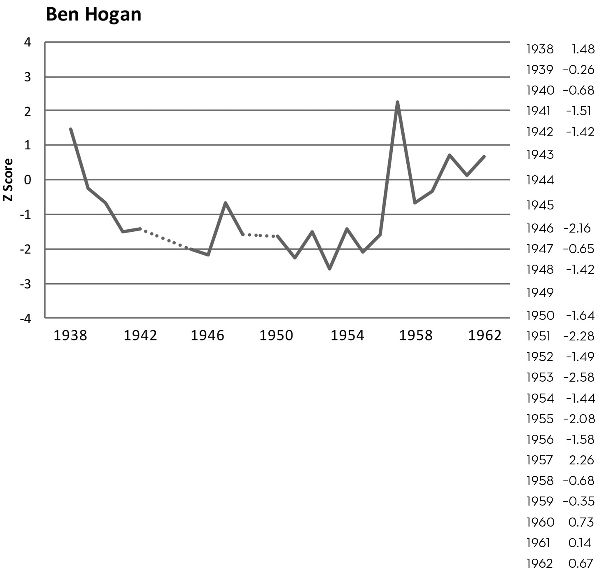

Ben Hogan

Number 9 Peak, Number 10 Career

Certain years take on a magical aspect, and that is certainly true of 1912 in golf. The strange coincidence by which a foursome of golf immortality arrived almost simultaneously actually began on November 22, 1911, when Ralph Guldahl was born in Dallas. Less than three months later, on February 4, 1912, Byron Nelson came to be in Fort Worth. On May 27, Sam Snead arrived in Ashwood, Virginia. That same year produced Ben Hogan, born August 13 in Dublin, Texas. In time the foursome would produce twenty-four major championships, and one can scour calendars from now till the Masters without finding any twelve-month period equaling that total.

Of the four, Hogan was the most prolific, with nine major titles to his credit: four U.S. Opens, two Masters, two PGAs, and a British Open the only time he played in it. This is especially noteworthy because among the four, Hogan was decidedly the latest bloomer and the one initially displaying the least promise.

Moving to Fort Worth at age nine when his father died, Hogan’s interest in golf developed out of his experience as a caddie, where he shared the shed with Nelson. He was twenty when he first tested himself professionally in 1932, and the experience nearly ruined him. A long hitter despite his small size, Hogan fought unsuccessfully to control a hook. He missed the cut at the 1934 U.S. Open, went broke, missed the cut at the 1936 Open, and went broke again. By this time, his old caddie tournament foe, Nelson, was the defending Masters champion, while Guldahl held the Open title and Snead was runner-up. A final-round 69 at an obscure tournament in Oakland garnered Hogan $380—badly needed capital—and a shot of confidence. “I played harder that day than I ever played before or ever will again,” he said later. His developing practice regimen with tour star Henry Picard also took hold. If there was one thing Hogan could do, it was practice. “Work never bothered me like it bothers some people,” he said.

While the results were not instantaneous, they were measurable. Invited to the 1938 Masters, he cobbled together four passable rounds to finish in a tie for twenty-fifth place at 301. The U.S. Open at Cherry Hills, a repeat victory for Guldahl, was another setback. For the third time in three tries, Hogan missed the cut. He did win the Hershey Four-Ball—the first of sixty-four championships he would eventually accumulate—and landed a top-ten finish at the 1939 Masters. His showing at the 1939 Open was unremarkable—a score of 308 and a sixty-second-place standing, 24 strokes behind Nelson—but at least he lasted all four rounds.

The war’s intervention obscured Hogan’s slow, steady progress, which included top-ten finishes in the final three Masters and two Opens before those events were halted. He missed thirteen major tournaments during the war, most of which were canceled entirely. Based on his prewar performance, projections suggest he might have dominated those events, compiling Z scores in excess of –2.00. That’s contender level. Those watching closely could see the signs: between 1940 and 1942, Hogan won thirteen tour titles, although almost all of them were at minor events.

With the war’s end, Hogan emerged with a game viewed by many as machinelike. Some ascribed the improvement to a weakened left hand that turned his unpredictable hook into a controlled fade. Hogan was more mysterious, asserting merely that his interminable practice sessions had uncovered “a secret.”

The record verified that something was afoot. He won ten times in 1946 alone, including the PGA, Colonial Invitational, and the Western Open, the latter by 4 strokes over Mangrum. Equally impressively, he was second at the Masters and third at the U.S. Open. More of the same followed in 1947, with wins at Los Angeles, Phoenix, Colonial, the World Championship of Golf, and Miami. He was again top five at both Augusta and the U.S. Open and in the fall captained the victorious Ryder Cup team. In 1948 Hogan underscored his breakthrough with an opening 67 at the Open at Riviera, using that as a springboard to a record four-run total of 276 and a 2-stroke victory. Nine more tour victories, including the U.S. Open at Riviera, the PGA, and the Western, strongly suggested that Hogan had supplanted Snead as the game’s premier figure.

What such a dominant player entering such a late and full prime might have done in 1949 will forever remain unknown. On February 2, Hogan and his wife, Valerie, were severely injured when a Greyhound bus crashed head-on into their car. He was sidelined for fourteen months, not returning until the 1950 Masters, where he trailed Jim Ferrier by just 2 strokes after three rounds. But a Sunday 76—perhaps attributable to the physical grind—dropped him into a tie for fourth place. It also solidified the suspicion among many that Hogan might never fully return to championship form.

At the U.S. Open that June at Merion, he entered the final thirty-six-hole Saturday in fourth place, 2 shots behind Dutch Harrison. His morning 72 placed him third, 2 shots behind Mangrum, and 1 behind Harrison. Fighting into the lead at the turn of the afternoon session, he felt his knees buckle on number 12, and he wobbled with three straight back-nine bogeys. Hogan came to the final hole, a 454-yard par 4, needing par to force a playoff with Mangrum and George Fazio. He drove the center of the fairway and then struck one of the game’s iconic shots—a perfect one-iron to the center of the green—to force the playoff. The next day Hogan shot 69 to win that playoff by 4 shots.

Either befitting his age or as a concession to his injuries, Hogan reduced his playing schedule after 1950. He never again played at the Western Open, and three of his five subsequent victories on the nonmajor portion of the tour came at his home club, Colonial. Yet as Hogan played less, he played better. In 1951 he finally won the Masters and followed that by taming the Oakland Hills “monster” to win his third U.S. Open, this time by 2 strokes. His 1953 season is the equal of any. A 5-stroke victory at Augusta, he humiliated the field at the U.S. Open at Oakmont, recording a 283 that was 6 shots superior to Snead, the runner-up, and 19 below the field average of 302. Then Hogan, who had never played in the British Open before, gave Carnoustie a try. The result was a 4-stroke triumph. For the three majors cumulatively, Hogan recorded a dominance score of 93.2. In 2000, when Tiger Woods won three of the four major events, his dominance score was 94.4. It is at least an arguable proposition that nobody has ever been better in the majors than Hogan was in 1953.

The British Open title was Hogan’s ninth and final major victory, but it was not his last shot at contention. Now forty-two, he lost to Snead in a playoff at the 1954 Masters, ran second to Cary Middlecoff at the 1955 Masters, and lost a playoff to club pro Jack Fleck at the 1955 U.S. Open. He lost to Middlecoff by a stroke again in the 1956 Open.

Hogan’s career record trails Nicklaus so substantially at least in part due to events out of Hogan’s control. The crash cost him a full season and probably reduced the number of his subsequent appearances. The war knocked out most of four more years, and the exigencies of cross-ocean travel and scheduling discouraged him from playing in more than a single British Open. Nicklaus played in 28 British Opens by age fifty and 112 majors overall, twice as many as Hogan. To the extent one chooses to believe projections, they speculate that the combined impact of the war and the 1949 crash cost Hogan the opportunity to participate in 17 major events, at which he might have improved his career Z score by close to 40 points. Hogan presently stands tenth on the career chart; give him those 40 points, and he leaps to second, behind only Nicklaus.

Hogan in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1950 Masters |

T-4 |

288 |

–1.62 |

|

1950 U.S. Open |

1st |

287 |

–1.66 |

|

1951 Masters |

1st |

280 |

–2.17 |

|

1951 U.S. Open |

1st |

287 |

–2.39 |

|

1952 Masters |

T-7 |

293 |

–1.29 |

|

1952 U.S. Open |

3rd |

286 |

–1.70 |

|

1953 Masters |

1st |

274 |

–2.60 |

|

1953 U.S. Open |

1st |

283 |

–2.98 |

|

1953 British Open |

1st |

282 |

–2.15 |

|

1954 Masters |

2nd |

289 |

–1.76 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.13. Effective stroke average: 68.84.

Hogan’s Career Record (1938–62)

- Masters: 21 starts, 2 wins (1951, 1953), –18.47

- U.S. Open: 18 starts, 4 wins (1948, 1950, 1951, 1953), –22.38

- British Open: 1 start, 1 win (1953), –2.15

- PGA: 8 starts, 1 win (1948), –5.11

- Western Open: 7 starts, 2 wins (1946, 1948), –4.98

- Total (55 starts): –53.09

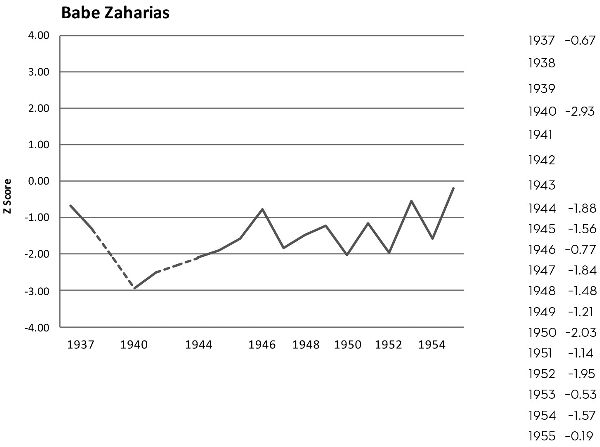

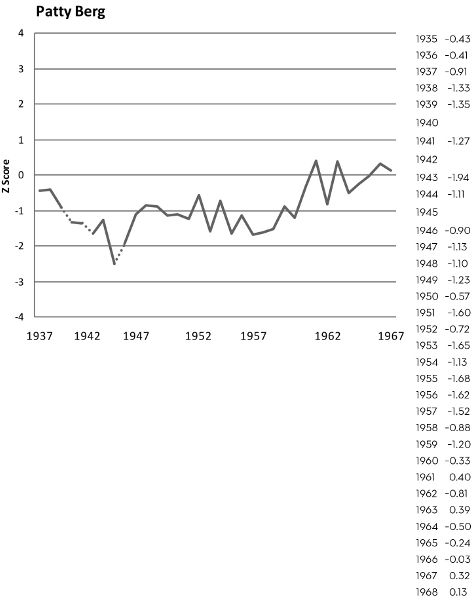

Babe Zaharias and Patty Berg

Number 23 Career and Number 3 Career, Respectively

The accomplishments of these two founding figures from the Ladies Professional Golf Association certainly justify separate consideration. Yet their careers were so inextricably overlapping, their competitions so headline grabbing, that the temptation for a joint assessment is overwhelming.

Zaharias was the older of the two by seven years, having been born in 1911 in Port Arthur, Texas. Yet the Babe’s international success at her first career—Olympic track and field star—meant they arrived at the attention of the golfing public virtually simultaneously. Following her victories at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, Zaharias dabbled in various efforts to translate her fame into some sort of paying proposition before finding that she was a natural at golf. She entered the inaugural Titleholders Championship in Augusta, Georgia, where the field included the nineteen-year-old Berg, an amateur from the University of Minnesota making her own debut on the game’s stage. Born February 13, 1918, to a grain merchant who belonged to the Interlachen Country Club, Berg turned her own focus to golf at thirteen and never stopped. She won the Minneapolis City Championship as a sixteen-year-old in 1934, later calling it “my proudest victory ever.”

With that as a spur, she placed second to Glenna Collett Vare in the women’s amateur in 1935. The veteran was duly impressed. Asked to rank the upcoming cohort of female players, Vare said, “By all means, Patty Berg first . . . in fact quite a distance ahead of the rest.”

Berg played the three rounds at Augusta in 1937 in 240 strokes, three ahead of the field and 21 better than the better-known Babe. Suddenly, the hitherto invisible women’s game had two dominant personalities, not one.

The Babe, who married wrestler George Zaharias in 1938, soon signed a contract with the Wilson Sporting Goods Company to endorse golf equipment—making her one of the few women pros at the time. In the amateur-driven game that was women’s golf, it also made her ineligible for most every tournament in existence at the time . . . including, for a few years, the Titleholders. That, coupled with the intervention of war and injuries, meant the Zaharias-Berg story line idled through several seasons. Berg returned to successfully defend her Titleholders championship in 1938, this time winning by 16 strokes against a field absent the Babe, and won for a third time in 1939, Zaharias again barred by her professional status from participating. The Babe traded on her name by playing exhibitions and occasionally challenging on the men’s tour, making one or two cuts. In June 1940 she teed it up in the Women’s Western Open—the most prestigious tournament open to women pros at the time—and scorched through five victorious matches without ever being taken to the eighteenth hole. Berg, having left the University of Minnesota to capitalize on her own burgeoning golf reputation, won the same tournament in 1941. Seriously injured in an automobile crash that December, she missed the 1942 season altogether but returned to repeat in 1943, this time as Lieutenant Berg, whose military assignment consisted of raising morale on the golf course. In neither of her wins did she face Zaharias, also idled by injuries and by her eventually successful fight to recoup her amateur status.

That meant their meeting at the 1944 Women’s Western was their first since that 1937 introduction at the Titleholders. It also marked the true start of their head-to-head rivalry. Between then and 1953, when Zaharias was sidelined by cancer, the two would collide at eighteen major events, seven at match play and eleven at stroke play, one or the other of them winning twelve of those eighteen. At the 1944 Women’s Western, Zaharias exacted a measure of revenge for her defeat by Berg at the 1937 Titleholders, cruising to the title again without ever playing the eighteenth hole. Berg was ousted in the quarterfinals. Zaharias added a third Women’s Western title in 1945, despite waking up on the morning of the semifinals to the news that her mother had died the previous night. She was reported to have tried to make emergency plane reservations home, but finding that impossible on the weekend committed to finishing the event. “I knew mother would have wanted me to win this championship,” she told reporters following her 4 and 2 finals win over Dorothy Germain.

Responding to interest generated primarily by Berg and Zaharias, the USGA created the Women’s Open in 1946, and Berg won it. At the 1947 Titleholders, the Babe—by then an acknowledged professional competing in a more tolerant atmosphere—bested Patty and the full field, winning by five strokes with Berg seven back in fourth. “The great distance she gets with her shots is just too much for the rest of us to contend with, and I don’t mind admitting it,” Dorothy Kirby, a two-time Titleholders champion, wrote in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution following her runner-up finish, five shots behind Zaharias. The two stars jointly dominated the women’s tour in 1948, Patty beating the Babe by a stroke at the Titleholders and Zaharias exacting revenge with an eight-stroke win at the Open—by now contested at medal play. Berg finished fourth, 13 back. That season’s Western constituted a fitting and epic conclusion, both players marching through the field to a final showdown, which Berg won on the thirty-seventh hole of the scheduled thirty-six-hole distance. The year 1948 was also the year that Zaharias filed papers to enter the men’s U.S. Open at Riviera, but tournament officials squelched that effort, citing a “men’s only” provision.

Though enthusiastic competitors, Berg and Zaharias also knew when to team up for maximum impact. So it was that in the late 1940s they provided the impetus behind creation of the Ladies Professional Golf Association, an effort to expand professional opportunities for the game’s best women players. Both players were at the zenith of their reputations, especially the Babe, whose boisterous personality was a natural promotional tool. “I’m here girls! Who’s going to finish second?” she was said to have made a habit of bellowing as she entered the locker room prior to tournaments. In 1950 Zaharias swept all three of the events that would come to be considered women’s majors, taking the Titleholders by eight strokes, the Open by nine, and winning the Western after ousting Berg 1-up in the semifinals. It was the Babe’s eighth of an eventual ten major championships; Berg by then had nine of her eventual fifteen. Patty added a tenth in 1951, capturing the Western after famously taking out Zaharias 1-up in a pulsating second-round battle punctuated by the Babe’s very verbal run-in with photographers. On the second hole, Zaharias drove into a bunker, blasted out, and missed the green with her third. “Okay, I suppose now you’ll want another picture,” she snapped at a photog she believed had distracted her on her swing. Striking an indifferent approach to the green, she angrily picked up her ball, telling Berg, “You can have this one, Patty; I can’t do anything with all this clicking.”

Zaharias evened that score at the 1952 Titleholders, beating Betsy Rawls by seven with Berg tied for third, eight back. Berg got her own revenge at the 1953 Augusta event, winning by nine with Zaharias tied for sixth, 18 strokes distant. It was the Babe’s final appearance before her cancer diagnosis. Her return in 1954 was triumphant—a third-place finish at the Titleholders, two behind Berg and nine in back of Louise Suggs—followed by an inspirational third U.S. Open victory. Wearing a colostomy bag, the Babe completed 72 holes in 291 strokes, 12 better than the field. “It will show a lot of people that they need not be afraid of an operation and can go on and live a normal life,” she said of her comeback. Noted sports columnist Jim Murray later termed it “probably the most incredible athlete feat of all time, given her condition.” The enthusiasm, however, proved transitory; the cancer returned, and by 1956 Zaharias was dead. On that day, President Dwight Eisenhower opened his press briefing by heralding her courage.

Berg by then was thirty-eight, still in her prime, a fact she proved by winning the 1955 Titleholders and Western, claiming both again in 1957 and adding a seventh Women’s Western in 1958. It was her fifteenth and final major win. She was the LPGA’s leading money winner in 1954, 1955, and 1957; won the Vare Trophy for lowest scoring average in 1953, 1955, and 1956; and was three times voted outstanding woman athlete of the year by the Associated Press. She was also the first woman to win $100,000 in career earnings. “The perfect golfer for a woman,” Mickey Wright called her.

The performances of Berg and Zaharias between the mid-1930s and the mid-1950s marked the most sustained era of joint dominance since the days of the British Triumvirate. Across the arc of their careers, Zaharias and Berg competed in the same field twenty-two times, fittingly each finishing ahead of the other in eleven. Babe won eight of those twenty-two events, and Patty won seven, leaving just seven others for the field. Between 1946 and 1955, Berg or Zaharias won at least one major championship nine times, the sole exception being 1949.

Zaharias in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1946 Women’s Western |

quarterfinals |

match play |

–1.66 |

|

1947 Titleholders |

1st |

304 |

–1.84 |

|

1948 U.S. Open |

1st |

300 |

–1.58 |

|

1948 Women’s Western |

2nd |

match play |

–1.74 |

|

1949 Titleholders |

4th |

304 |

–1.20 |

|

1949 U.S. Open |

2nd |

305 |

–1.26 |

|

1949 Women’s Western |

quarterfinals |

match play |

–1.17 |

|

1950 Titleholders |

1st |

291 |

–2.91 |

|

1950 U.S. Open |

1st |

291 |

–1.83 |

|

1950 Women’s Western |

1st |

match play |

–1.35 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.65. Effective stroke average: 69.54.

Zaharias’s Career Record (1940–55)

- Titleholders: 10 starts, 3 wins (1947, 1950, 1952), –11.48

- U.S. Open: 6 starts, 3 wins (1948, 1950, 1954), –7.78

- Women’s Western Open: 11 starts, 4 wins (1940, 1944, 1945, 1950), –16.51.

- Total (27 starts): –35.77

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1953 Titleholders |

1st |

294 |

–2.62 |

|

1953 U.S. Open |

3rd |

303 |

–1.72 |

|

1954 Titleholders |

2nd |

300 |

–1.49 |

|

1955 Titleholders |

1st |

291 |

–2.29 |

|

1955 Western Open |

5th |

307 |

–1.59 |

|

1956 LPGA |

2nd |

291 |

–1.91 |

|

1956 Titleholders |

2nd |

303 |

–1.90 |

|

1957 Western Open |

1st |

291 |

–1.92 |

|

1957 Titleholders |

1st |

296 |

–2.23 |

|

1957 U.S. Open |

2nd |

305 |

–1.49 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.92. Effective stroke average: 69.15.

Berg’s Career Record (1935–68)

- U.S. Amateur: 4 starts, 1 win (1938), –2.39

- Titleholders: 23 starts, 7 wins (1937, 1938, 1939, 1948, 1953, 1955, 1957.) –25.27

- U.S. Open: 23 starts, 1 win (1946). –13.32.

- LPGA: 11 starts, 0 wins, –4.93

- Western Open: 23 starts. 7 wins (1941, 1943, 1948, 1951, 1955, 1957, 1958). –27.30.

- Total (84 starts): –73.21

The top-ten golfers of all time for peak rating as of the end of the 1950 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score | Effective stroke average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

James Braid |

1901–10 |

–2.18 |

68.76 |

|

2. |

Bobby Jones |

1926-30 |

–2.11 |

68.87 |

|

3. |

Walter Hagen |

1923–27 |

–2.10 |

68.88 |

|

4. |

Harry Vardon |

1896–1904 |

–2.03 |

68.98 |

|

5. |

Ralph Guldahl |

1936–40 |

–2.02 |

69.00 |

|

6. |

Sam Snead |

1946–50 |

–2.01 |

69.01 |

|

7. |

Byron Nelson |

1937–41 |

–1.984 |

69.06 |

|

8. |

Gene Sarazen |

1929–33 |

–1.976 |

69.06 |

|

Ben Hogan |

1946–50 |

–1.86 |

69.23 |

|

|

10. |

Jim Barnes |

1919–23 |

–1.81 |

69.31 |

The top-ten golfers of all time for career rating as of the end of the 1950 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Walter Hagen |

1913–40 |

–73.94 |

|

2. |

Gene Sarazen |

1920–50 |

–57.54 |

|

3. |

Byron Nelson |

1933–50 |

–46.28 |

|

4. |

Jim Barnes |

1913–31 |

–44.58 |

|

5. |

Macdonald Smith |

1910–37 |

–43.15 |

|

6. |

Bobby Jones |

1916–30 |

–39.62 |

|

7. |

J. H. Taylor |

1893–1920 |

–38.70 |

|

8. |

Harry Vardon |

1893–1914 |

–37.88 |

|

9. |

Sam Snead |

1937–50 |

–34.69 |

|

10. |

Jock Hutchison |

1908–30 |

–34.43 |

The top-ten golfers of all time for peak rating as of the end of the 1960 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score | Effective stroke average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

James Braid |

1901–10 |

–2.18 |

68.76 |

|

2. |

Ben Hogan |

1950–54 |

–2.13 |

68.84 |

|

3. |

Bobby Jones |

1926–30 |

–2.11 |

68.87 |

|

4. |

Walter Hagen |

1923–27 |

–2.10 |

68.88 |

|

5. |

Sam Snead |

1947–51 |

–2.06 |

68.94 |

|

6. |

Ralph Guldahl |

1936–40 |

–2.02 |

69.00 |

|

7. |

Harry Vardon |

1896–1904 |

–2.03 |

68.98 |

|

8. |

Byron Nelson |

1937–41 |

–1.984 |

69.06 |

|

9. |

Gene Sarazen |

1929–33 |

–1.976 |

69.06 |

|

10. |

Patty Berg |

1953–57 |

–1.92 |

69.15 |