9

The Golden Bear Market

Large presences dominated American golf during the 1970s. First among these, of course, was Jack Nicklaus, who emerged from a modest late-1960s pause in his brilliance to dominate the men’s tour even more decisively than he had done in wresting attention from Arnold Palmer. He was not, however, alone.

The marvelously entertaining and skilled Lee Trevino chased—and often caught—Nicklaus through the period. In mid-decade Tom Watson rose from his Midwest roots by way of Stanford to stage a series of memorable battles. The most memorable: their classic performance at the 1977 British Open when the two men surged jointly away from the rest of the field.

The women’s tour, meanwhile, grew its own personalities and for the first time matured into a stable sports enterprise. The smallest winner’s pure on the women’s tour virtually doubled—from $11,200 to $22,200—during the 1980s. The largest grew from $37,500 (to the winner of the Dinah Shore) in 1979 to $80,000 in 1989. At the same time, two media darlings with starkly contrasting approaches vied for attention on the tour. Longtime amateur champion JoAnne Gunderson Carner turned pro and took advantage of her power. Then from out of the New Mexican desert, young Nancy Lopez arrived in 1978, smilingly playing her way to nine victories that season alone, five of them in succession.

The intensity of the Nicklaus-Trevino rivalry surfaced during their memorable duel at Merion for the 1971 U.S. Open title. “Jack is the greatest golfer who ever picked up a club,” Trevino said of Nicklaus.”1 Theirs was a mutual-admiration society. His one wish going into the tournament, Nicklaus famously said, was that “Trevino never finds out how good he is.”2 Word evidently got to Trevino, who shot a final-round 69 to post a score of even par 280, tying Nicklaus for first. Jack missed a fourteen-foot birdie putt on his final hole, setting up an eighteen-hole playoff on Monday.

Jack Nicklaus

Number 3 Peak, Number 1 Career

What separates the great players from the golfing pack is often a four- or five-year window of dominance. The history of modern professional golf is laced with talented players—Scott Simpson, Larry Nelson, and Ken Venturi—who capped solid careers with one or even two major titles. But they were frequently in-and-outers. Simpson followed his 1987 U.S. Open title by tying for sixty-second at the British Open a month later. Two months before winning the 1983 U.S. Open, Nelson missed the cut at the Masters. Between that Open victory and 1987, Nelson would add one PGA Championship—but he would also miss seven more cuts. In the five seasons following his fabled 1964 Open victory at Congressional, Venturi made the top five in just one more major.

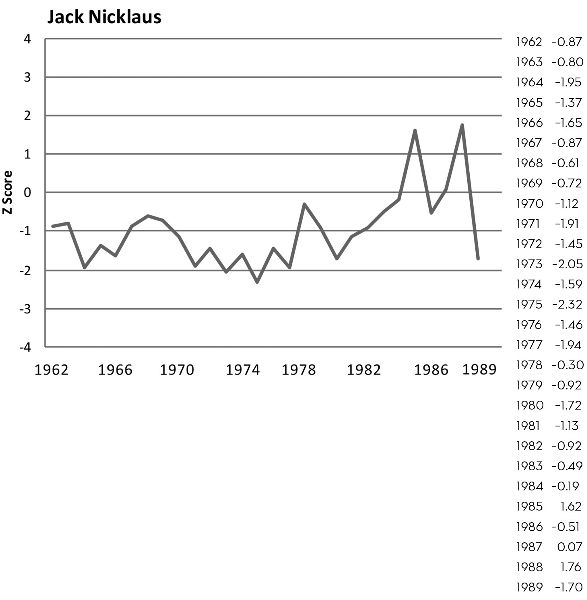

The great players not only win but dominate over a sustained period. What distinguishes Jack Nicklaus’s record from the stellar pack is not merely that he dominated over a sustained period but that he did it twice.

Between 1962 and 1966, Nicklaus was nearly the equal of Arnold Palmer. Arnie won six majors, but so did Jack. Palmer won more tour titles over that 1960–66 period, but the bulk of those came prior to 1963, when Nicklaus was just beginning to burnish his reputation. “It is frightening to think what this boy may do in the years to come,” Byron Nelson told reporters following Nicklaus’s 1965 Masters victory.3 Nicklaus’s peak rating for 1962–66—the average standard deviation of his ten most dominant performances in major tournaments for that period—is –2.27. If in 1966 anybody had thought to calculate a Z score for golfers, Nicklaus would have stood second on the all-time list for peak performance, barely trailing Palmer’s 1960–64 peak of –2.30.

It would be an overstatement to suggest that Nicklaus’s performance slackened dramatically between 1966 and 1970. He did, after all, win both the 1967 U.S. Open and the 1970 British Open, and he consistently beat the field averages in those seasons’ majors. But in comparison with the standards he had set, there was a slowdown. Between 1962 and 1966, Nicklaus won six majors with four runners-up and thirteen top fives; between 1967 and 1970, he won two, finished second three times, and made seven top fives. This relative retreat sparked speculation that the man known as the Golden Bear for his physique and blond hair had lost his edge.

Nicklaus may have sensed the same thing, for in capturing the 1970 Open at St. Andrews—surviving a playoff with Doug Sanders—he sounded simultaneously energized and refocused. “There is no place in the world I would rather win an Open championship than here,” he told the playoff spectators. Then he added, in what turned out to be a portent, “It is some while since I won a championship . . . and I have never been so excited in my life.”4

Excited and energized. Between 1971 and 1975, Nicklaus compiled a performance résumé even steadier and stronger than what he had done a decade earlier. He added six more major titles and twenty more tour championships, improving his 1962–66 Z score. “Nicklaus has now reached a pinnacle of achievement comparable only to those of Bobby Jones and Ben Hogan,” remarked Pat Ward-Thomas, adding, in a concession to the obvious, “In every sense of the term Nicklaus is the world’s greatest golfer.”5

So dominant was Nicklaus that if you considered only his ten worst performances in majors between 1971 and 1975, his Z score would still be a very respectable –1.33, roughly the equal of Tony Jacklin’s best.

Jack Nicklaus had done something that is rarely accomplished in athletics. He had set a full, mature, lofty, and functionally complete standard of performance . . . then starting from scratch he had bettered it. This was the kind of determination that by the mid-1970s led many golf experts to refer to Nicklaus as the greatest player who ever lived. “He plays a game with which I am not familiar,” Bobby Jones famously observed following Nicklaus’s romp at the 1965 Masters. Jones was referring both to the immensity of Nicklaus’s power and to the immensity of his competitive determination. His could be a crushing presence.

Mathematicians estimate that in any set of data—say, tournament golf scores—only about 3 percent of scores will fall more than two standard deviations below the tournament’s average performance level. In a field of fifty players, that means maybe one or two players might shoot such a strikingly low score. For the twenty majors played between 1962 and 1966, Nicklaus reached the 2-standard-deviation indicator of dominance eight times, his best being a –3.48 during that 1965 Masters that awed Mr. Jones. Then between 1971 and 1975, he topped even that, with ten such exceptional performances . . . three of them in 1975 alone. For his career, Nicklaus recorded twenty-seven such performances in the majors.

Born January 21, 1940, in Columbus, Ohio, Nicklaus was introduced to golf early. The relationship took. He won the 1956 Ohio State Open at age sixteen and then won the U.S. Amateur in both 1959 and 1961. In between, he tied for second behind Palmer at the 1960 U.S. Open.

Nicklaus came to the pro tour as a stout dynamo with a mighty upright swing that allowed him to hit the ball high, long, and straight. But the game had seen bombers before. Nicklaus could also hit devastatingly precise long irons, such as his clinching one-iron to the final hole of the 1967 U.S. Open at Baltusrol. His putting touch was considered unusually consistent.

Playing Nicklaus, tour players sometimes felt as if they had no chance. Why should they feel otherwise? Between 1962 and 1986, he won seventy official events, a total that remains second all time behind only Sam Snead. He won twenty majors—two U.S. Amateurs, a record six Masters, a record-tying four U.S. Opens, three British Opens, and a record-tying five PGAs. That’s a triple Grand Slam, plus change.

What many consider Nicklaus’s best season unfolded in 1972. He won the Masters in April and the U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, both by three strokes over Bruce Crampton, then finished just one stroke back of Trevino at the British Open. Statistically, however, his best was yet to come. In 1973 he won the PGA, finished no worse than fourth in the majors, and averaged a –2.05 Z score, the best of his career. But it was not by much: he opened 1975 with a one-stroke victory over Johnny Miller and Tom Weiskopf at Augusta, followed with seventh- and third-place finishes at the Opens, and then won the PGA by two over Crampton, averaging –2.04.

Nor did he retreat much as age reduced his physical skills. For twenty-two consecutive seasons well into the 1980s, Nicklaus unfailingly beat the field scoring average in major events. He did so without exception in the British Open annually between 1963 and 1982, a twenty-year window of performance. During the same twenty-year window, he beat the field average eighteen times at the Masters, seventeen times at the U.S. Open, and sixteen times at the PGA. Merely to equal Nicklaus’s run, a player starting out today would have to beat the field average performance in the majors every season through 2037. It is a daunting thought, indeed.

Nicklaus only scored worse than the field average in 22 of his 111 majors between 1962 and 1989, 12 of those coming after 1982. You won’t find many players who can string together ten consecutive seasons with Z scores better than –1.14. Between 1972 and 1981, Jack Nicklaus did.

Nicklaus in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1971 U.S. Open |

2nd |

280 |

–2.00 |

|

1971 PGA |

1st |

281 |

–2.40 |

|

1972 U.S. Open |

1st |

290 |

–2.72 |

|

1972 British Open |

2nd |

279 |

–2.31 |

|

1973 Masters |

T-3 |

285 |

–1.98 |

|

1973 British Open |

4th |

280 |

–2.21 |

|

1973 PGA |

1st |

277 |

–2.27 |

|

1974 British Open |

3rd |

287 |

–2.08 |

|

1975 Masters |

1st |

276 |

–2.47 |

|

1975 PGA |

1st |

276 |

–2.57 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.30. Effective stroke average: 68.59.

Nicklaus’s Career Record (1962–89)

- Masters: 27 starts, 6 wins (1963, 1965, 1966, 1972, 1975, 1986), –31.56

- U.S. Open: 28 starts, 4 wins (1962, 1967, 1972, 1980), –19.62

- British Open: 28 starts, 3 wins (1966, 1970, 1978), –31.39

- PGA: 28 starts, 5 wins (1963, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1980), –21.98

- Total (111 starts): –104.55

Lee Trevino

Of the men who arose at various times to challenge Nicklaus’s superiority, the most colorful was Lee Trevino. “The Merry Mex” emerged from the obscurity of South Texas municipal courses to place fifth at the 1967 U.S. Open won by Nicklaus and ratified that newfound fame by winning the following year’s Open at Oak Hill. In the process, he defeated Nicklaus by four shots.

Trevino fitted nobody’s formula for a golf genius. Born in 1939, he was raised in a three-room Dallas shack, not a suburban development, and spent his time working the cotton fields, not the country club. “I thought hard work was just how life was,” he said. His biggest break was geographic: as modest as the family’s home was, it happened to be just a hundred yards from the seventh fairway of the Dallas Athletic Club. By the time Trevino was eight, he had wangled a job caddying. “That’s where I learned my killer instinct, playing games with the caddies and betting everything I had earned that day,” he wrote. It also toughened him to tournament pressure. “Pressure,” he once famously remarked, “is when you play for $5 and you’ve got $2 in your pocket.”6 He quit school in eighth grade to work at a driving range, where he would hit hundreds of balls a day. Lessons? Trevino taught himself, manufacturing balls and clubs out of whatever material could be brought to the task.

The experiences Trevino acquired came in handy when he joined the Marines and was assigned to what in effect was the golf team. A natural hustler, he took his discharge papers and set out to find money games around Dallas and El Paso, one of which included his hitting the ball around a par-three course with a Dr. Pepper bottle.

Trevino’s signature move was a controlled fade. It gave him a distinctive swing, dominated by a strong grip, a body alignment well left of his target, and a consistent blocking action of his left side. It was a case of three wrongs somehow making a right. “Who knows, maybe my method is best,” Trevino said.

Trevino was a virtual overnight success. By 1971, just five years after winning tour privileges, he held two U.S. Open titles, one British Open championship, and eight more tour championships. He added a second British Open in 1972, chipping in from off the green at the seventy-first hole of what had evolved into a head-to-head showdown to beat Tony Jacklin at Muirfield. His tour résumé included five Vardon trophies: 1970, 1971, 1972, 1974, and 1980.

Where Trevino’s fade bias frequently caught up with him was Augusta National, a place noted as favoring the right-to-left player. Between 1970 and 1977, he skipped the Masters four times and on the occasions when he did play only once did well. That was in 1975, when he shot 286 to tie for tenth. In 1971, following a second consecutive no-show, Jack Nicklaus took Trevino aside for something between a pep talk and a lecture. “You can win anywhere,” Nicklaus told him. It turned out to be one of the few times in his professional life that Nicklaus was wrong. Trevino returned to the Masters and finished in a tie for thirty-third, 14 strokes behind Nicklaus.

Perhaps oddly, considering how far removed the roots of his game were from the classical British model, Trevino often saved his best showings for the British Open. In addition to winning in 1971 and 1972, he finished third in 1970 and second in 1980. In twenty-three British Opens played during his prime—between 1969 and 1992—Trevino missed just one cut.

Trevino in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1968 U.S. Open |

1st |

275 |

–2.62 |

|

1968 PGA |

T-23 |

288 |

–0.64 |

|

1969 Masters |

T-19 |

290 |

–0.18 |

|

1970 U.S. Open |

T-8 |

294 |

–0.97 |

|

1970 British Open |

T-3 |

285 |

–1.87 |

|

1971 U.S. Open |

1st |

280 |

–2.00 |

|

1971 British Open |

1st |

278 |

–2.37 |

|

1972 U.S. Open |

T-4 |

295 |

–1.82 |

|

1972 British Open |

1st |

278 |

–2.49 |

|

1972 PGA |

T-11 |

286 |

–1.22 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.62. Effective stroke average: 69.59.

Trevino’s Career Record (1966–92)

- Masters: 20 starts, 0 wins, +13.31

- U.S. Open: 23 starts, 2 wins (1968, 1971), +11.63

- British Open: 23 starts, 2 wins (1971, 1972), –11.60

- PGA: 20 starts, 2 wins (1974, 1984), –1.95

- Total (86 starts): +4.26

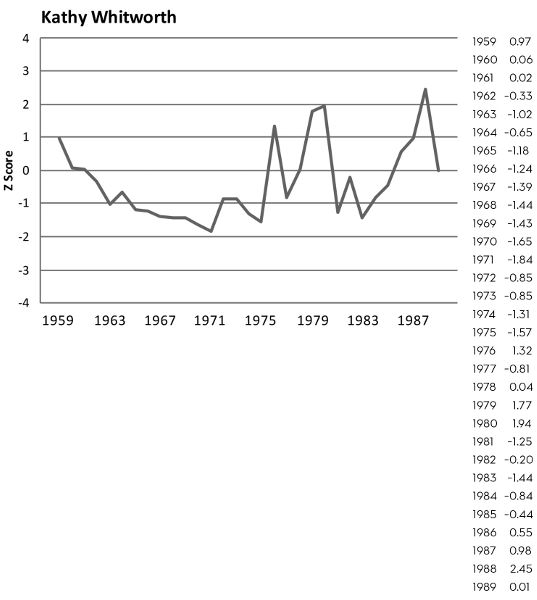

Kathy Whitworth

Number 24 Career

As of the end of 2017, Tiger Woods still needed three tournament titles to equal Sam Snead’s PGA tour record of eighty-two. But if or when he does pass Snead, Woods will still be a half-dozen wins short of the all-time professional record, Kathy Whitworth’s remarkable eighty-eight LPGA tour victories between 1963 and 1985.

Whitworth’s secret was consistency. “I never had a golf swing,” she said, incorrectly, for she was a competent technician.7 In the eleven seasons from 1963 to 1973, she led the money list eight times and stood second twice and third the other year. During that stretch, she won the Vare Trophy and Player of the Year honors seven times each.

A native of the Southwest, Whitworth started playing golf at fifteen. Two years later, she won the first of two consecutive New Mexico State Amateur titles. But she initially struggled on the LPGA tour, winning less than $1,300 in her rookie season. Whitworth’s big break may have been the sisterly attitude that pervaded the tour at the time. She credited Mickey Wright, Betsy Rawls, Gloria Armstrong, and Jackie Pung all with boosting her flagging confidence, and with offering useful tips. By 1963 Wright and Rawls may have come to regret their beneficence. Previously winless, Whitworth won eight times that year and counted the Titleholders among eight more championship trophies in 1965. In 1968 she topped even that with eleven tournament titles. By then she’d already claimed a second Titleholders as well as the 1967 LPGA and Western Open.

Confidence? Momentum? Whitworth suddenly had it. “When I won eight tournaments in 1963, I was living on a high,” she said. “I got in a winning syndrome. Nothing bothers you.”8

Whitworth was only just entering her competitive prime. Following her LPGA triumph in 1967, she lost in a playoff to Sandra Post in 1968, lost to Shirley Englehorn in another playoff in 1970, and got her second victory by four strokes over Kathy Ahern in 1971. Although she did not win any of the three Opens between 1969 and 1971, Whitworth compiled an unmatched record. She finished third by two strokes to Donna Caponi in 1969, lost again to Caponi by two in 1970, and was runner-up to JoAnne Carner in 1971.

What Whitworth never showed was weakness. During her professional prime, roughly 1963 to 1977, she competed in forty-seven LPGA majors. In addition to winning six of them—the last being the 1975 LPGA—she beat the field average in forty-four of those tournaments, thirty-two in succession. She missed just one cut.

By then Whitworth was focused on passing Wright, holder of the women’s championship record, and Snead, both of whom had eighty-two titles. She matched them at the 1981 Kemper Open and passed them with a victory at the 1982 Lady Michelob. “Winning got harder as I got older and there were more players,” she said. Yet despite her record victory total, Whitworth is not persuaded those eighty-eight victories put here among the game’s elite. “I still say that if Mickey Wright hadn’t quit playing so early, there’s no telling how many tournaments that woman would have won,” she said.9

Her final victory came at the 1985 United Virginia Bank Classic. In retirement Whitworth stayed active in golf as vice president, and eventually president, of the LPGA.

Whitworth in the Clubhouse

Note: Average Z score: –1.73. Effective stroke average: 69.43.

Whitworth’s Career Record (1959–89)

- Titleholders: 7 starts, 2 wins (1965, 1966), –6.90

- U.S. Open: 28 starts, 0 wins, –8.15

- LPGA: 22 starts, 2 wins (1967, 1971), –13.19

- Western Open: 7 starts. 1 win (1967), –5.46

- Dinah Shore: 7 starts, 0 wins (Whitworth won in 1977 before the tournament was considered a major), –2.01

- du Maurier: 10 starts, 0 wins, +1.03

- Total (81 starts): –34.68

Tom Weiskopf

There was a time when the young Tom Weiskopf looked like he might be the next Jack Nicklaus. Both were tall sluggers from Ohio State, Weiskopf arriving in Columbus just as Nicklaus was starring there. Weiskopf came to the pro tour in 1964, just as Nicklaus’s star was poised to supersede Arnold Palmer’s, and the legitimate prospect loomed that the two Buckeyes might soon challenge one another for the top of the money chart.

For various reasons—some ascribed it to inexperience, others to Weiskopf’s occasionally volcanic temper—that challenge never truly took hold. Weiskopf started more than seventy tournaments before finally winning—at the 1968 San Diego Open—in the process finishing no higher than fifteenth at any of the handful of majors for which he actually qualified. That San Diego win kick-started a 1968 campaign that was lucrative by comparison: he tied for sixteenth in his first appearance at the Masters, tied for twenty-fourth at the U.S. Open, and in July won a second event, the Buick. At the following spring’s Masters, Weiskopf came to the seventy-first hole in a tie for the lead with George Archer, only to bogey and fall back into a tie for second. In the years to come, he would conduct a flirtatious romance with the Masters, finishing second four times but never winning.

Weiskopf’s stride may have been delayed in coming, but when it arrived—in 1972—it was impressive. He again tied for second at Augusta—although this time three strokes behind Nicklaus—finished eighth at the U.S. Open and tying for seventh at the British Open. Third behind Johnny Miler’s remarkable closing 63 at the 1973 U.S. Open, he flew to Troon for that summer’s British Open as one of the favorites. Weiskopf shot an opening 68, led start to finish, and posted a record-tying total of 276. It was exactly how everybody had always envisioned he would play.

“The game was easy, fun. I was relaxed,” Weiskopf said. “I had unbelievable confidence, and I kept working, pushing.” The champion also drew inspiration from the death of his father the previous March. “I felt like I’d let him down [with my play].”10

The Troon win was Weiskopf’s only major trophy but hardly his only moment in the spotlight. Coming off a bout with tendinitis that hampered his swing during the winter tour in 1974, he tied for second a third time at Augusta, this time 2 strokes behind Gary Player. One spring later, Weiskopf led the Masters after three rounds, only to be overtaken by Nicklaus’s final-round 66. Weiskopf came to the eighteenth hole needing birdie to force an eighteen-hole playoff and watched an eight-foot downhill putt slide by on the right side.

Weiskopf was fast becoming Mr. Near Miss. His fifth runner-up finish in a major unfolded at the 1976 U.S. Open at the Atlanta Athletic Club when he finished 2 strokes behind Jerry Pate. He was third at the 1977 Open, and fourth in both 1978 and 1979. That gave him a dozen finishes of fourth or better in PGA Tour majors, yet only one victory. “I had a great run, with four consecutive top-4 finishes (in the Open) from 1976 through 1979,” he would say later. “But I couldn’t get it done.” Why not? Weiskopf could only speculate. “I had trouble dealing with the fame,” he acknowledged.11

His tour résumé still showed sixteen career victories and sixty-eight finishes in the top three. But Weiskopf began reducing his playing schedule after 1980 and essentially quit the tour in 1984 to focus on what was becoming a burgeoning golf course design business. Assessing his career, Golf magazine saw “a golf swing to die for, a mixture of grace and power” that was occasionally derailed by a bad temper and a knack for becoming flustered. It described him as “a linear perfectionist who somehow didn’t attain the greatness expected of him.”

Weiskopf never disagreed. Asked by the magazine whether he had maximized his potential, Weiskopf replied, “Emphatically, no.” Taking no exception with that self-critique, a lot of PGA Tour regulars would love to put together a résumé that includes one major championship, five runner-up finishes, a dozen placings in the top five, and twenty-one in the top ten, all accompanied by sixteen career tour victories and more than $2.2 million in winnings.

Weiskopf in the Clubhouse

Note: Average Z score: –1.80. Effective stroke average: 69.32.

Weiskopf’s Career Record (1965–92)

- Masters: 16 starts, 0 wins, –5.20

- U.S. Open: 17 starts, 0 wins, –8.23

- British Open: 17 starts, 1 win (1973), +9.66

- PGA: 17 starts, 0 wins, +9.94

- Total (67 starts): +6.17

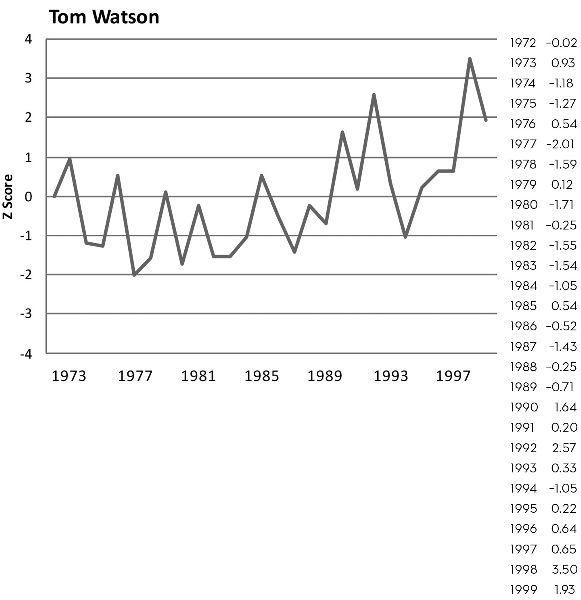

Tom Watson

Number 8 Peak

There was an aw-shucks quality to Tom Watson, a fair-haired kid from Kansas City who came out of Stanford to compete with, and eventually supplant, Nicklaus as the tour’s most predictable winner. Even more than his alter ego, Trevino, Watson was especially deadly in Britain, winning the British Open five times, a total exceeded only by Harry Vardon. They were among his eight major championships and thirty-nine tour titles.

Watson was a made golfer. At Stanford, he established a decent but not especially noteworthy reputation on the links, actually doing better in the classroom, where professors predicted a fine career for him in psychology. Watson, however, had other ideas. He took his college golfing experience to the tour, working and working to hone his game. “Tom would never tolerate a weakness,” said Lanny Wadkins. “He’d go to the practice tee and beat at it until the darn thing went away.”12

The “darn thing” didn’t go away easily. At the 1974 U.S. Open at Winged Foot, Watson, trying for his first professional victory, took a 1-stroke lead into the final round. A 79 dropped him to fifth. Victory a week later at the Western Open may have been some consolation. At the 1975 U.S. Open, Watson held the thirty-six-hole lead but finished 78-77 to fall into a tie for ninth. “I learned how to win by losing and not liking it,” he said later in his career.13

His solution was more effort. Making his debut at the British Open that summer at Carnoustie, Watson stood over a twenty-foot birdie putt on the seventy-second hole to get into a playoff with Jack Newton. He made the putt and then beat Newton by a stroke the next day.

From that point on, England and Scotland were virtual second homes to Watson . . . especially if he was battling Nicklaus.

Their personal duel reached its first of several high points in 1977. Watson had already taken Nicklaus’s measure at that spring’s Masters, birdieing four of the final six holes to defeat Jack by two strokes. In the British Open at Turnberry that July, the two renewed the Augusta showdown, engaging in what some have called the most intense and highest-caliber sustained battle in the history of major championship golf.

Jointly tied for second with Lee Trevino at 68 after the opening round, and with Hubert Green and Trevino after two rounds, they flew from the field on Saturday with matching 65s. It was the third successive day on which they had tied each other.

As Sunday dawned, 10 strokes separated them from third place. Nicklaus got the first edge with a birdie at the second and moved 3-up with a birdie at the third, while Watson bogeyed. Watson birdied the fifth, seventh, and eighth to draw even, and then Nicklaus regained the lead at the ninth when Watson bogeyed. By the turn on that final day, they were 8 and 7 shots ahead of their nearest challenger. A long putt boosted Nicklaus’s lead to two shots at the twelfth. But Watson drew even again with birdies of his own at the thirteenth and fifteenth, the latter on a 60-footer.

The break came at seventeen when Nicklaus failed to birdie the 500-yard par 5. Watson did and led by 1. At eighteen, Nicklaus drove into the gorse, then improbably thrashed out of it and onto the green leaving a 20-foot putt. Watson, meanwhile, played straight down the middle and knocked an iron just a few feet from the hole. Nicklaus, needing his long putt for an unlikely birdie to retain any prospect of tying, holed out to the delight of a roaring throng for a 66. But Watson tapped in his as well for a 65 and a 1-shot win in a head-to-head duel for the ages. Watson would repeat as British Open champion in 1980, 1982, and 1983.

Watson added the 1981 Masters to his laurels, and then his personal wrestling match with Nicklaus resumed at the 1982 U.S. Open at Pebble Beach. There Jack aimed for a record fifth title. Nicklaus led until Watson chipped in from the fringe on the seventeenth hole for an improbable birdie to take the lead. His follow-up birdie at eighteen made the margin of victory 2 strokes.

By the time he retired from regular tour competition in the late 1990s, Watson had won thirty-nine events and six Player of the Year awards and had led the money list five times.

Watson in the Clubhouse

Note: Average Z score: –2.17. Effective stroke average: 68.78.

Watson’s Career Record (1973–99)

- Masters: 25 starts, 2 wins (1977, 1981), –12.94

- U.S. Open: 28 starts, 1 win (1982), +2.63

- British Open: 24 starts, 5 wins (1975, 1977, 1980, 1982, 1983), –4.59

- PGA: 27 starts, 0 wins, –1.91

- Total (104 starts): –16.81

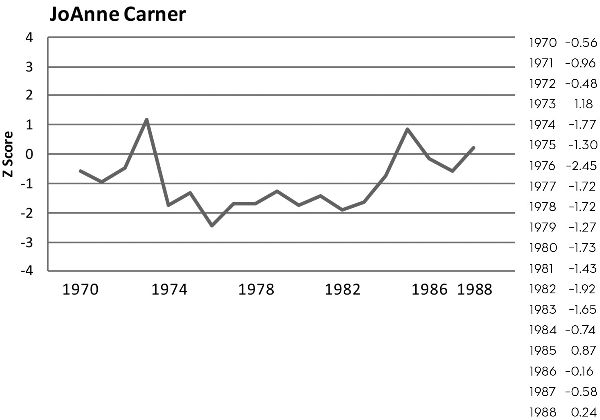

JoAnne Carner

Number 15 Career

Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, fans of women’s golf might have debated who—Whitworth, Nancy Lopez, Sandra Haynie—was the best player. But the choice, whoever it might have been, always ended up being compared to the oversize, overenergetic, and overtalented Carner.

A precocious teen amateur with a soaring reputation when she initially rose to fame in 1959, the girl known at the time as JoAnne Gunderson (or more simply “the Great Gundy”) offered a first demonstration of her talent at the 1959 Western Open. There, while still a teenager, Gunderson battled the tour’s best on equal terms, finishing in a tie with Patty Berg for second place, behind only Betsy Rawls and ahead of such established stars as Louise Suggs and Marlene Hagge.

For years following that debut, Gunderson contented herself with dominating the amateur ranks. Between 1956, when she lost to Marlene Stewart, and 1968, Gunderson—Carner after her 1963 marriage to her coach and business manager—won the Women’s Amateur title five times and was runner-up in seven more. The match-play format seemed to especially suit Carner’s gallery-pleasing personality.

Both in her dominance and in her crowd-friendly nature, Carner drew comparisons to legends of the stripe of Babe Ruth and Walter Hagen. Away from the course, though, Garner exhibited far simpler tastes than Hagen or the Babe. No fancy suites for her; she often traveled to events in a Gulfstream driven by her husband, who used it to catch fish for dinner while she was on the course. “I play better golf living in our trailer,” Carner explained.14

Finally, in 1969, Carner forsook the amateur life for that of a professional, where she was the immediate hit everybody predicted she would be. She dominated the field at the 1971 U.S. Open, defeating Whitworth by 7 strokes and posting a score of 288 that was 21 strokes below the field average for the week. In classic Ruthian form, power was her trademark. “The ground shakes when she hits it,” Sandra Palmer said of Carner.15

She was on her way to forty-one championships—including an encore victory at the 1976 U.S. Open, this time in a playoff over Palmer. Three times she was Player of the Year and five times the Vare Trophy winner, and she consistently led in body language and crowd reaction. In the process, the kid once known as “the Great Gundy” acquired a new nickname: Big Momma. Carner wallowed in the interaction.

“Concentration and getting involved with the shot are important,” she said, “but if I get too serious I can’t play.” Unlike many players who tend to cocoon themselves from galleries, Carner seemed at times almost to be her own gallery. “If the ball is going for the pin or in the cup, I am the first one to yell,” she conceded.16

Perhaps befitting a stage personality, Carner was at her best in the big events. In her thirty-eight U.S. Open or LPGA appearances between 1970 and 1989, “Big Momma” made every cut but one and beat the field average twenty-seven times. Carner’s first appearance in the LPGA’s year-old major, the 1980 du Maurier (then called the Peter Jackson Classic), saw her wage a marvelous duel with Pat Bradley, eventually losing by a stroke.

Carner in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1980 LPGA |

T-3 |

289 |

–1.60 |

|

1980 du Maurier |

2nd |

278 |

–2.63 |

|

1981 LPGA |

T-5 |

284 |

–1.63 |

|

1982 LPGA |

2nd |

281 |

–1.98 |

|

1982 du Maurier |

T-3 |

283 |

–2.18 |

|

1982 U.S. Open |

T-2 |

289 |

–1.61 |

|

1983 du Maurier |

T-2 |

279 |

–1.94 |

|

1983 U.S. Open |

T-2 |

291 |

–1.77 |

|

1984 Nabisco |

T-5 |

284 |

–1.65 |

|

1984 du Maurier |

5th |

284 |

–1.60 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.86. Effective stroke average: 69.23.

Carner’s Career Record (1970–88)

- Titleholders: 1 start, 0 wins, –0.79

- U.S. Open: 18 starts, 2 wins (1971, 1976), –18.95

- LPGA: 18 starts, 0 wins, –10.96

- Nabisco Dinah Shore: 6 starts, 0 wins, –3.89

- du Maurier: 8 starts, 0 wins, –8.45

- Total (51 starts): –43.04

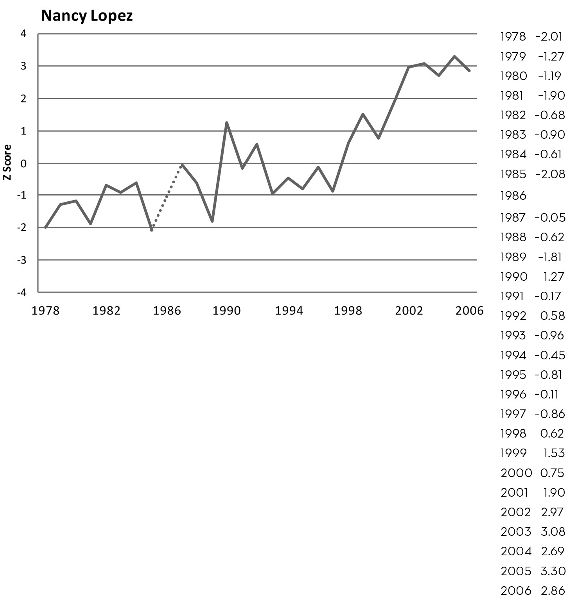

Nancy Lopez

Nancy Lopez’ explosion on tour in 1978 could not have been better timed. A wave of LPGA stars had either retired (Wright, Rawls, Suggs, Haynie) or were past their prime (Berg, Hagge). Whitworth, although a superb shot maker, was perceived as largely colorless. Jan Stephenson had plenty of personality but had not yet established the consistent game. That left only JoAnne Carner as a figure around whom women’s golf could mobilize interest.

Then sprang Lopez with a background almost as unlikely as Lee Trevino’s to snare all the attention the tour could have hoped for. The daughter of a Roswell, New Mexico, shop owner, Lopez was a prodigy. In 1970, at age twelve, she won the New Mexico Women’s Amateur. Because her high school did not have girls’ golf, she joined the boys’ team and led it to two state championships. At Tulsa she became an All-American, and in 1975 she won the Mexican Amateur. That same year she came to the tour as a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) champion, qualified for the U.S. Open, and tied Carner for second behind Sandra Post.

By 1977 Lopez’s successes persuaded her to leave Tulsa and try the women’s tour. In her first event, the Women’s International, she tied for fortieth. Her second start, the 1977 Open, went a bit better; she finished second again, two shots behind Hollis Stacy. In her third start, two weeks later, she posted another runner-up finish. In February 1978, Lopez, who had just turned twenty, won for the first time, edging JoAnn Washam by a single shot at Bent Tree.

That was the start of one of the most remarkable runs in the history of women’s golf. A week later Lopez won a second time, defeating Debbie Austin by a stroke at the Sun Star Classic. A week after that at the Kathryn Crosby, she lost a playoff to Sally Little. In May and June, she added five more titles, including the LPGA Championship by a stifling 6 shots over Amy Alcott. Lopez played the four rounds in 13 under par, including a second-round 65 that was 2 strokes better than anybody else managed all week. Her total was a full 20 shots below the field average of 295 strokes. Seemingly, LPGA events had suddenly become flighted competitions, with Lopez in the first flight and everybody else in the second.

Before the year was out, Lopez added two more championships to her résumé along with another playoff loss. Her card for the year showed nine victories. Eight more tour wins followed in 1979. So did an unprecedented amount of endorsement money and publicity for a successful young girl with a natural and infectious smile and an evident love of the game. She had plainly overcome her biggest fear—of failure. “After my first year I thought, ‘I could be a flash in the pan,’ and I was also determined to prove I was not,” Lopez has said. “I was determined not to fall on my face, though it is easy enough to choke yourself to death trying to win.”17

The amazing thing was that looking strictly at her performance in the majors, Lopez could have been even better. Aside from the 1978 LPGA victory, she largely had to content herself with close calls in the tour’s biggest events. Lopez did win two more LPGA Championships, in 1985 and 1989. But she never got closer to a U.S. Open title than those two early runner-up finishes, and her second place to Stephenson at the 1981 du Maurier was her best showing in that major. She was runner-up there three times.

Overall, Lopez finished second seven times in recognized LPGA majors, the last at the 1997 U.S. Open when the thirty-nine-year-old’s last-gasp effort at the event that most frustrated her included shooting four rounds in the 60s. Lopez was the first women to do that, yet she still lost by 1 stroke to Alison Nicholas.

The golf nation hung on every shot of that drama, pulling for the popular veteran, a three-time Vare Trophy winner. “I’d love to have won the Open,” Lopez once said. “But I’ve had enough good things in life that I won’t be shattered because I don’t.”18

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1985 Nabisco |

T-11 |

285 |

–1.13 |

|

1985 LPGA |

1st |

273 |

–3.58 |

|

1985 U.S. Open |

T-4 |

288 |

–1.51 |

|

1988 Nabisco |

T-5 |

282 |

–1.61 |

|

1988 LPGA |

T-24 |

291 |

–0.45 |

|

1988 U.S. Open |

T-12 |

288 |

–0.82 |

|

1989 Nabisco |

T-18 |

291 |

–0.73 |

|

1989 LPGA |

1st |

274 |

–3.30 |

|

1989 U.S. Open |

2nd |

282 |

–1.75 |

|

1989 du Maurier |

9th |

283 |

–1.46 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.63. Effective stroke average: 69.57.

Lopez’s Career Record (1977–2006)

- Nabisco Dinah Shore: 21 starts, 0 wins (Lopez won the Shore in 1981, before it was classified as a major), +5.03

- U.S. Open: 21 starts, 0 wins, –2.01

- LPGA: 25 starts, 3 wins (1978, 1985, 1989), –1.50

- du Maurier: 11 starts, 0 wins, –9.51

- Total (78 starts): –7.99

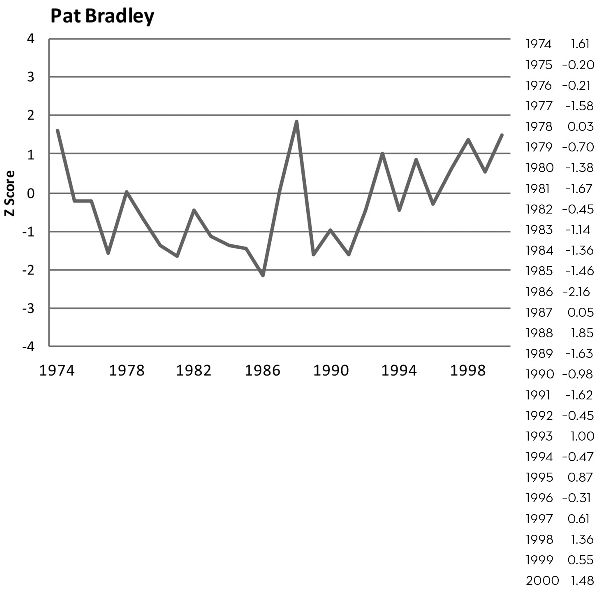

Pat Bradley

Number 22 Peak

Pat Bradley was not a long hitter, a great putter, or a crowd favorite. But she was consistent and determined, and she rarely hurt herself. Beyond that, Bradley savored the challenge of teeing it up. The combination brought her riches beyond any previous women’s golfer. It also brought her as close to completing the single-season professional Grand Slam as any other player has come.

Workaholic? Between 1974 and 2000—essentially her golfing prime—Bradley competed in 627 tournaments and finished in the top ten 312 times and in the top five 208 times, with thirty-one victories. On the way, she became the first woman golfer to surpass the $2 million (1986), $3 million (1990), and $4 million (1991) marks in career earnings. When she won three of the women’s majors in 1986, Bradley became the first modern woman to complete the career Grand Slam.

Although Bradley came to the tour virtually at the same time as Lopez and Beth Daniel, she did not share their quick success. For her, it was a building process. Her potential surfaced in 1977, when the twenty-six-year-old in her fourth season on tour tied veteran Judy Rankin and Jane Blalock for fifth at the Colgate Dinah Shore. She made a serious run at two majors, shooting 282 at the LPGA to tie Rankin and Sandra Post for second and a few weeks later at the U.S. Open tying Jan Stephenson and Amy Alcott for fourth.

Bradley made a second run at the Shore in 1979, tying Donna White for third. The close misses proved to be dress rehearsals for the 1980 Peter Jackson Classic, when Bradley withstood Carner’s final-round charge to win by 1 stroke to win at 277, 15 under par. It was a case of honesty paying off; at the seventh hole, Bradley—seeing her ball move imperceptibly as she addressed it—had imposed a 1-stroke penalty on herself. A five-foot birdie putt at the sixteenth gave her the lead she barely held onto when Carner missed her own thirty-foot birdie putt on the final hole. An Open title followed in 1980, Bradley beating Daniel by a stroke.

In 1986 Bradley entered the first major, the Shore, off a winter run that included two runner-up finishes, a fourth, and a third the previous week at Tucson. She won by two over Val Skinner, following that with another runner-up and then a victory at the S&H Golf Classic in late April.

Bradley claimed her fourth second place at the Corning Classic, a prelude to the LPGA Championship in June. Again she won, this time with an imposing score of 277, 11 under par and 1 better than Patty Sheehan. With the Nabisco and LPGA titles, Bradley could lay claim to the career slam, having captured the Open in 1981 and the du Maurier in 1985. Four behind Sally Little entering the final round of the U.S. Open, she was among a tight group of nine players with a chance to win on Sunday afternoon. Bradley pieced together a closing 69, but Jane Geddes’s own 69 and Little’s 71 left her in a tie for third, 3 strokes away from her third major of the year. Geddes won a playoff with Little the next day.

Two weeks later, Bradley defeated Ayako Okamoto in a playoff at the du Maurier, giving her four of the last five Grand Slam events. Her average Z score for that season’s majors was –2.16. “I honestly wish everyone could experience what I did in that dream-come-true year,” she would say later. “I was invincible.”19

The 1988 death of her father, and her own medical problems, cut into Bradley’s success in 1987 and 1988, although she still managed a third place at the 1987 Nabisco. But she returned in 1989 with a season rivaling 1986 in consistency, if not in hardware. Virtually written off when the season began, she finished sixth in the Shore, fourth in the LPGA, third in the Open, and second in the du Maurier.

Three more victories followed in 1990 and then four more in 1991, enough to ensure her entrance into the LPGA Hall of Fame. After 1991 Bradley was only an occasional threat on tour, although she maintained a full schedule through 2000.

Bradley in the Clubhouse

Note: Average Z score: –1.98. Effective stroke average: 69.06.

Bradley’s Career Record (1974–2000)

- Nabisco Dinah Shore: 18 starts, 1 win (1986), –12.38

- U.S. Open: 26 starts, 1 win (1981), –3.64

- LPGA: 26 starts, 1 win (1986), –14.28

- du Maurier: 21 starts, 3 wins (1980, 1985, 1986), –1.81

- Total (91 starts): –32.11

The top-ten golfers of all time for peak rating as of the end of the 1980 season.

The ten golfers of all time for career rating as of the end of the 1980 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Jack Nicklaus |

1962–80 |

–101.71 |

|

2. |

Walter Hagen |

1913–40 |

–73.94 |

|

3. |

Patty Berg |

1935–68 |

–73.21 |

|

4. |

Sam Snead |

1937–62 |

–68.69 |

|

5. |

Mickey Wright |

1954–80 |

–62.22 |

|

6. |

Louise Suggs |

1948–72 |

–60.31 |

|

7. |

Gene Sarazen |

1920–51 |

–58.09 |

|

8. |

Ben Hogan |

1938–62 |

–53.09 |

|

9. |

Byron Nelson |

1933–60 |

–44.88 |

|

10. |

Jim Barnes |

1913–31 |

–44.58 |