11

Millennials

Since the PGA and LPGA Tours began keeping records of such things, only three men and four women have compiled season-long scoring averages that were at least one stroke lower than all of his or her competitors. The three men who did that were: Tiger Woods in 2000, Tiger Woods in 2007, and Tiger Woods in 2009. The four women were Annika Sorenstam annually from 2002 through 2005.

As a practical matter, the question of whether Tiger Woods is the best golfer in history ultimately comes down to whether he was better than Annika Sorenstam at her peak or Jack Nicklaus over the course of his career.

The Tiger Woods story is well-enough known that its details need only be touched upon here. How he was raised as the only child of an American military man and an Asian woman. How his golf skills first went on display on The Mike Douglas Show at the age of three. How relentless training, both physical and mental, gave him the skill and will to dominate junior golf. How he became the youngest winner in the history of the U.S. Amateur and then won it twice more in succession. How he focused, from the effective start of his life, on becoming a golf champion. How he dominated. Finally, how it all somehow came apart just at the moment when it appeared Woods would become generally recognized as the greatest ever at his sport.

Woods was not alone in his exceptionality. Sorenstam dominated the women’s tour almost in parallel fashion. She won 72 of her 307 career starts—that’s 23 percent—competitive with Woods’s 24.5 percent. Jack Nicklaus, by comparison, won 12 percent of his events, Sam Snead won 14 percent, and Lorena Ochoa won 16 percent. In 2004 Sorenstam started eighteen LPGA tournaments and won eight of them—by an average of three strokes. Sorenstam’s worst finishes that season were a pair of ties for thirteenth place in fields of 99 and 124. More than 160 LPGA Tour members played for $42.075 million in purses in 2004; Sorenstam won $2,544,707, or 6 percent, of the total purse.

Tiger Woods and Annika Sorenstam

Woods: Number 1 Peak, Number 5 Career Sorenstam: Number 2 Peak, Number 8 Career

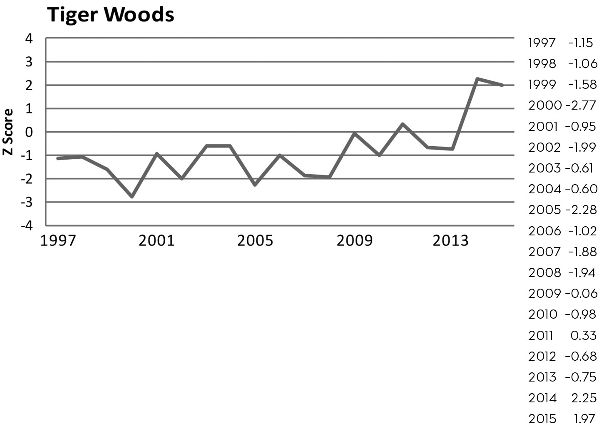

Let’s begin with Woods. The first of his three Amateur victories earned him a spot in the 1995 Masters. By the standards of amateur rookies, he didn’t embarrass himself, making the cut and shooting a four-round score of 293 to finish in a tie for forty-first. At the 1996 British Open, Woods began a streak of twenty-eight consecutive majors—extending seven years—in which he always outshot the field average.

Woods’s pro debut in the fall of 1996 nearly coincided with the beginning of the period of his greatest dominance. His first major as a professional was an overpowering statement, victory at the 1997 Masters by a dozen strokes over Tom Kite. Tiger got the same production out of fewer than 93 shots that it took Kite 96 to accomplish and that it took the average player 100 to achieve. The rest of 1997 would have been considered satisfactory for any pro—certainly for any tour rookie—except Woods. He placed nineteenth in the U.S. Open, twenty-fourth in the British Open, and twenty-ninth at the PGA.

It was a solid base from which to build, and Tiger did. In 1998 he was eighth at the Masters, eighteenth at the U.S. Open, third at the British Open, and tenth at the PGA. Woods climbed to number 1 in the Official World Golf Ranking, a perch he would retain every year but one through 2009. He followed a so-so performance at the 1999 Masters by placing fourth behind Payne Stewart at the Pinehurst U.S. Open, claimed seventh place at the British Open at Carnoustie, and then defeated Sergio Garcia by 1 shot at the PGA at Medinah. His 277 four-round total that week translated to a Z score of –2.53, a performance level that ought to be reached less than 1 percent of the time. Tiger would exceed it four more times in majors before the end of 2002.

The PGA victory also set the stage for the phenomenal 2000 season. It opened pedantically by Tiger’s standards and his alone, in fifth place behind Vijay Singh at Augusta. Two months later at the Pebble Beach U.S. Open, he mounted his memorable one-man show against the wind, sea, and nature, winning by 15 shots at 272. Against the field average of 296, this amounted to a Z score of –4.12, making it the best performance in the history of major tournament golf to that date. When he added the British Open a month later by 8 shots, it came as that rarest of things on tour, a foregone conclusion. His 269 score translated to a Z score of –3.33. The PGA fell in another month with a –2.27 Z score that seemed almost unexceptional by comparison with his recent efforts. Woods’s average Z score in majors during the 2000 season was –2.77, the best one-season Z score in major tournament history. Here’s how it compares to the best years of some other fellows:

|

Tiger Woods |

2000 |

–2.77 |

|

Ben Hogan |

1953 |

–2.58 |

|

Bobby Jones |

1930 |

–2.23 |

|

Arnold Palmer |

1964 |

–2.22 |

|

Sam Snead |

1949 |

–2.14 |

|

Jack Nicklaus |

1973 |

–2.05 |

Woods’s 2001 Masters victory—climaxing the “Tiger Slam”—highlighted what for him was a disappointing season. His –0.95 average Z score for that year’s majors failed to exceed –1.00 for the first time since he turned pro. In other words, his average effort was only about 1.67 times as good as his fellow pros rather than twice as good. Victories in the 2002 Masters and U.S. Open—both with Z scores better than –2.50—restated his continued dominance.

In 2003 and again in 2004, Woods’s numbers moderated, although hardly pushing into the realm of “worrisome.” He won both the 2005 Masters and the British, making that year his best since 2000. He hit age thirty in December and after a frustrating 2006 put together his fourth exceptional season in 2007. Entering 2008, so high were expectations that even Woods talked openly about completing a calendar Slam. It didn’t happen, as we all know. He placed second in the Masters, three strokes behind Trevor Immelman, and then won that astonishing playoff victory over Rocco Mediate in the U.S. Open at Torrey Pines. Treatment followed for the fractured leg that sidelined him during the rest of 2008. He returned in 2009, placed sixth in the Masters and U.S. Open, and then came in second at the PGA. Although he had failed to win a Masters, it was a good year for Woods, his only flub coming at the British Open, where he had failed to make the cut. In the other three majors, all top-ten finishes, his Z score ranged from –1.1 (at Augusta) to –2.0 in the PGA. He appeared to be fully recovered . . . until that Thanksgiving weekend.

Since the infidelities surfaced and the injuries followed, Woods’s performance has been decidedly more sporadic and less impressive.

There was a point not so long ago when Woods was on pace to overtake Jack Nicklaus on the career list. But the years since his 2008 U.S. Open victory have not been kind to that goal. Beginning in the spring of 2010, his record in twenty contested majors shows a best finish of third (in the 2012 Brit), four fourths, one sixth, nine placings outside the top ten, and five missed cuts. He also failed to get to the post a dozen times through 2017. A word about those nine placings outside the top ten: between his professional debut in the majors in 1997 and 2009, Tiger had just eighteen placings outside the top ten. He also had fourteen victories.

Were one to run a peak rating for Tiger Woods from 2011 through 2015, his decline is obvious. The average Z score of his ten best majors during that period is –0.65—in short, on the good side of mediocre. His place on the career chart has also eroded. At the end of the 2013 season, he ranked second, behind only Jack Nicklaus, for career value. Entering his 2018 comeback attempt he had fallen to fifth, and the only thing that kept him from falling further appeared to be his inability to play. His performance in the 2018 season’s first major, the Masters, resulted in a tie for thirty-second, damaging his career Z score by another 0.40.

Woods has always been viewed as an exceptional driver of the golf ball. Certainly, that aspect was rarely if ever a weakness. The Strokes Gained data conclude that in 2005 and 2006, Woods picked up 0.8 and 0.9 of a stroke per round respectively off the tee. But it also suggests that, at least beginning in 2004, the true strength of his game lay in the breadth of his skills. Here are Woods’s annual Strokes Gained slash lines for 2004 through 2007:

| Skill | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Off the tee |

0.32 |

0.90 |

0.80 |

0.62 |

0.66 |

|

Approaching the green |

0.87 |

0.86 |

2.07 |

1.65 |

1.36 |

|

0.34 |

–0.02 |

0.11 |

0.10 |

0.13 |

|

|

Putting |

0.85 |

0.66 |

0.46 |

0.71 |

0.67 |

|

Net |

2.38 |

2.40 |

3.43 |

3.08 |

2.82 |

This relatively orgasmic profile shows a player generally deriving nearly half of his prodigious 2.82 stroke advantage over the field via his accuracy from the fairway, not his abilities off the tee or on the green. Not that those represent weaknesses. In fact, if Woods near his peak—there aren’t actually Strokes Gained data for Woods at his peak—had any weakness, it lay in his play around the green, where his margin against the field generally was minimal.

To a degree, one can also use the Strokes Gained data to analyze the reasons behind Woods’s decline. Those data exist for only two of his postdominant seasons, 2012 and 2013. They show a player whose abilities off the tee had declined into the average to low-average range but whose approach skills remained strong. His pitching and chipping skills, never strong, remained midpack. By 2012 and 2013, Woods was a less dominant but still slightly above-average putter, generally retaining about half his previous advantage in that aspect of play.

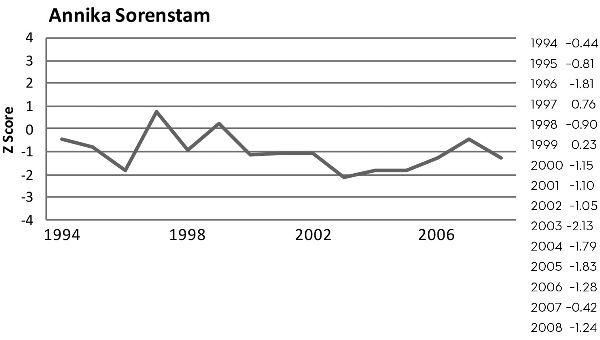

On to Sorenstam. Like, it seems, three-quarters of successful golfers past and present, she credits her parents for spurring her interest in the sport. Certainly, it’s a family trait, as evidenced by the fact that her sister, Charlotta, was also an LPGA Tour member. At sixteen Sorenstam qualified for the Swedish National Team. Even then she had leading-lady ability.

What she did not have—or at least she wasn’t sure she had—was championship desire. That changed with the 1988 victory of fellow Swede Lisolette Neumann at the U.S. Open. However much Neumann’s victory did for Neumann, it gave Sorenstam a role model and motivation. A participant in the World Amateur Golf Team Championships in both 1990 and 1992, she won the championship in that second effort.

By then Sorenstam had come to America and immersed herself in the profound experience that is college golf. At the University of Arizona, she became the first foreigner and first freshman to win the NCAA individual championship. She came close to dominating the amateur headlines in 1992, winning the Pac-10 Championship, being named to the All-American team, finishing second in the voting for National Player of the Year, and also finishing second at the Women’s Amateur, to Vicki Goetze. She qualified for the U.S. Open but found the competition a bit stout, finishing in a tie for sixty-third.

Following graduation in 1993, Sorenstam operated mostly on the European tour, getting a limited taste of U.S. tour play via sponsors’ exemptions. Her first full season here was 1994, and she lived up to expectations, winning the Rookie of the Year Award, although failing to win any of her eighteen starts. She remained winless entering the 1995 Women’s Open in mid-July, but she wasn’t winless leaving it. Five strokes behind veteran Meg Mallon entering Sunday play, Sorenstam recorded a final round of 68 to take the $175,000 first prize by a single shot.

If the golf world was surprised by this young foreigner’s success, Sorenstam forced a quick attitude adjustment. In 1996 she repeated her Open victory, this time by a persuasive 6 strokes. That came atop a runner-up finish at the Nabisco Dinah Shore. By the time of her Open encore, the twenty-five-year-old Sorenstam was already working on her second golf fortune, having passed the $1 million mark in career earnings a month earlier when she finished fourteenth at the McDonald’s event. During the season, Sorenstam won three times and won her second straight Vare Trophy for lowest season scoring average. Six wins followed in 1997, and then four more in 1998, when she became the first woman in LPGA history to record a stroke average below 70. Meanwhile, the official money poured in. By 1999 she had topped $6 million in career earnings. Nor had Sorenstam peaked yet. In 2000 Annika began a streak of six seasons in which she posted at least five tournament victories a year. That streak included the 2001 Nabisco, seven more victories, and probably Sorenstam’s most famous round, a 59 she recorded in the Standard Register Ping.

Statistically, Sorenstam’s peak performances in the LPGA majors didn’t even begin until 2002, a season in which she made twenty-five starts and won thirteen times. Sorenstam was fully capable of hijacking the biggest events. Between 2002 and 2006, she posted a score more than 2 standard deviations below the field average in nine of the twenty majors that were played. She won six of those twenty, and the intimidating factoid is how many more she might have won with garden-variety fortune. At the 2002 U.S. Women’s Open at Prairie Dunes, a course that yielded a field average of 291, Sorenstam posted a 278, a total nearly 3 standard deviations below the norm. Shoot 3 standard deviations below the field average, and you almost always win. But Juli Inkster went Sorenstam 2 strokes better, reaching 3.4 standard deviations below the field average, the eighth most dominant showing in the history of the LPGA Tour. Sorenstam was stuck with second place.

The same thing happened at the 2003 Kraft Nabisco. Sorenstam shot a four-round total of 282, a score that was 2.26 standard deviations below the field average of 296. Of the 276 women who completed four rounds of major tournament competition in 2003, only one posted a score that was more than 2.26 standard deviations below the field average. That golfer was Patrice Meunier-LeBlanc, whose 281 beat Sorenstam by a stroke.

Again in the 2004 Women’s Open, Sorenstam went inordinately low. Her 276 was 2.28 standard deviations outside the field average of 290. Of the 291 golfers completing four rounds of major competition that year, only 3 beat Sorenstam’s 2.28. The best was Sorenstam herself, with a score 2.99 standard deviations below the field average at the LPGA. One of the others was Meg Mallon, whose 274 consigned Sorenstam to second place in that Open.

Generally speaking, though, Sorenstam made the women’s tour boring. In 2006 she won the U.S. Women’s Open again, her tenth major title, tying her for the third most wins of all time. That victory pushed her over the $19 million mark in career earnings, a record.

Based on correlatable data, Sorenstam’s profound edge lay in her exceptional ability to hit greens in regulation. Sorenstam was the poster child for the value of this skill. During her peak seasons, between 2002 and 2006, the average margin by which Sorenstam’s performance in GIR exceeded the field average was 2.68 standard deviations, never falling below 2.02. In fact, during the eleven-season period between 1996 and 2006, Sorenstam’s average GIR margin of excellence was 2.59, an extraordinary period of extended execution at the game’s most sensitive skill. Across those eleven seasons, Sorenstam reached 76 percent of her greens in regulation; her competitors averaged 63 percent. No contest.

Sorenstam retired in 2008 with a career Z score of –59.16. Whether she ranks as the greatest golfer—or at least the greatest female golfer—of all time can be reasonably debated. But based on her record, Annika’s name has to be in the discussion.

Woods in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1998 British Open |

3rd |

281 |

–1.95 |

|

1999 U.S. Open |

T-3 |

281 |

–2.07 |

|

1999 PGA |

1st |

277 |

–2.53 |

|

2000 U.S. Open |

1st |

272 |

–4.12 |

|

2000 British Open |

1st |

269 |

–3.33 |

|

2000 PGA |

1st |

270 |

–2.27 |

|

2001 Masters |

1st |

272 |

–2.21 |

|

2002 Masters |

1st |

276 |

–2.55 |

|

2002 U.S. Open |

1st |

277 |

–2.71 |

|

2002 PGA |

2nd |

278 |

–2.30 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.60. Effective stroke average: 68.15.

Woods’s Career Record (1997–2016)

- Masters: 18 starts, 4 wins (1997, 2001, 2002, 2005), –24.40

- U.S. Open: 17 starts, 2 wins (2000, 2002), –16.38

- British Open: 17 starts, 3 wins (2000, 2005, 2006), –12.84

- PGA: 18 starts, 4 wins (1999, 2000, 2006, 2007), –11.00

- Total (70 starts): –64.62

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2002 LPGA |

3rd |

284 |

–1.95 |

|

2002 U.S. Open |

2nd |

278 |

–2.94 |

|

2003 Kraft Nabisco |

2nd |

282 |

–2.26 |

|

2003 LPGA |

1st |

278 |

–2.14 |

|

2003 British Open |

1st |

278 |

–2.33 |

|

2004 LPGA |

1st |

271 |

–2.91 |

|

2004 U.S. Open |

2nd |

276 |

–2.28 |

|

2005 Kraft Nabisco |

1st |

273 |

–2.99 |

|

2005 LPGA |

1st |

277 |

–2.68 |

|

2006 U.S. Open |

1st |

284 |

–2.37 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.49. Effective stroke average: 68.31.

Sorenstam’s Career Record (1994–2008)

- Kraft Nabisco: 14 starts, 3 wins (2001, 2002, 2005), –19.87

- U.S. Open: 15 starts, 3 wins (1995, 1996, 2006), –11.80

- LPGA: 14 starts, 3 wins (2003, 2004, 2005), –21.66

- du Maurier: 6 starts, 0 wins, –2.33

- British Open: 8 starts, 1 win (2003), –3.50

- Total (57 starts): –59.16

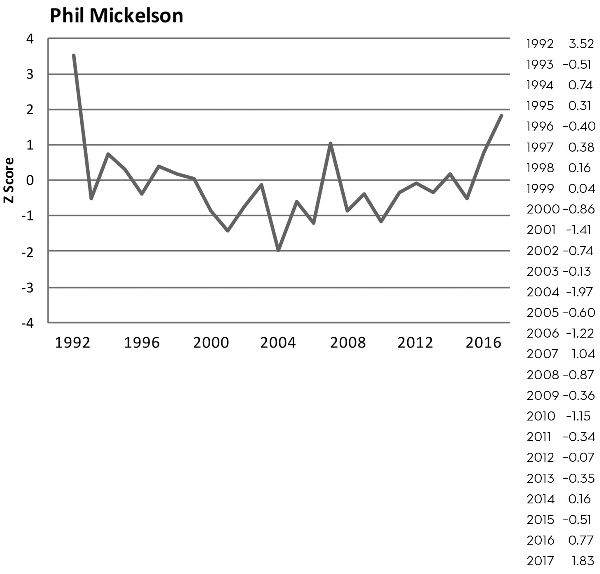

Phil Mickelson

Number 17 Peak

Through the 1990s and several years into the twenty-first century, Phil Mickelson piece by piece constructed a reputation as a great player—except when it really mattered. In regular tour events, his was a record to envy. As a college student in 1991, he won the Tucson Invitational. Turning pro the following season, he needed only four starts in 1993 to win again, this time the Buick Invitational. In 1994 he beat the tour’s best at the Mercedes. Through 1998 Mickelson never failed to reach the winner’s circle at least once.

By the spring of 2004, Mickelson had won twenty times on tour and finished in the top five on more than forty other occasions. Yet none of those aspects of his career identified Mickelson in the public mind. This one did: no majors.

It hadn’t been for lack of contending. In a dozen years as a pro, Mickelson was often perceived as a major contender and not just because his left-handed game, length off the tee, flowing curls, and college-hero (at Arizona State) background made him stand out. In the 1994 PGA, the twenty-four-year-old came home third, although 7 strokes behind champion Nick Price. At Shinnecock in 1995, he stood just a stroke off the pace after three rounds but succumbed to the pressure applied by a hard-charging Corey Pavin on Sunday. Mickelson shot 74 and Pavin posted 68 and won by 3, Mickelson consigned to a tie for fourth.

That round marked Mickelson as a guy who made the big one a tribulation. In 1996 he won four times and was positioned to take advantage of Greg Norman’s epic collapse at the Masters. Instead, he posted a pedestrian 72 for third place, while Nick Faldo shot the winning 67.

At the 1999 U.S. Open at Pinehurst, Mickelson added real-life melodrama to his usual golfing version. He arrived at the course packing a cell phone so his wife—expecting their first child literally any day—could summon him off the course in the event she went into labor. Mickelson shot an opening 67 to tie for the lead. He followed with rounds of 70 and 73 to stand one stroke behind Payne Stewart and one ahead of Tiger Woods as the final Sunday began. For one of the game’s frontline figures, positioned to capture his first major, there was a story line: Which Mickelson would deliver first? When Stewart holed a fifteen-foot putt on the final hole to beat him by a stroke—and with Mickelson watching him do it—skill averted fate. The next morning, Mickelson became a papa. Had a playoff been necessary, he said he would have forfeited it.

The 2001 majors were Mickelson’s most consistently successful but also in many ways his most frustrating. He finished third to Woods and David Duval at the Masters and tied for seventh at the Open at Southern Hills. As at Shinnecock in 1995 and Pinehurst in 1999, it wasn’t that simple. His first three rounds had consistently improved: a 70, then a 69, then a 68. He stood fifth but just 2 shots behind an unimposing leader board that nowhere included Tiger Woods, Vijay Singh, or Ernie Els. Then on Sunday Mickelson ballooned to a 75 and fell to a tie for seventh. As it turned out, a 69—his average round for the week to that point—would have put him in a playoff with Retief Goosen and Mark Brooks. Two months later at the PGA, Mickelson fired three consecutive rounds of 66, followed by a 68. Nice, but not nice enough. David Toms beat him by a stroke. He was third at the Masters in 2002, second to Woods at the 2002 Open at Bethpage Black, and second again at the 2003 Masters. Mickelson had become a self-parody: Mr. Close.

He put that identity to rest at the 2004 Masters, holding off Ernie Els’s final-round charge to win by a stroke. Freed from his goblins, Mickelson did not exactly run off on a long-delayed tear, but he did follow up. He turned in statistically his best performance at the 2004 Open, although finishing runner-up to Goosen. At the British Open, a Sunday 68 barely missed getting him into a playoff in which Todd Hamilton upset Els. Mickelson finished sixth at the PGA but won the event the following year. He added a third major, his second Masters, in 2005.

Mickelson turned forty-seven midway through the 2017 season, but that has not slowed him down. He added a third Masters in 2010, won the 2013 British Open, and has landed seven top fives. None were more dramatic than his July 2016 battle with Henrik Stenson for what would have been Mickelson’s second British Open. He opened with a record-tying 63 and finished 17 under par. Although losing to Stenson by 3 strokes, Micklelson at least had this. His –3.07 Z score was the third best in major tournament history by a nonwinner, trailing only 1966 U.S. Open playoff loser Arnold Palmer (–3.42) and Jack Nicklaus (–3.23) in his 1977 loss to Tom Watson at Turnberry.

Mickelson’s reputation as a long driver is well earned. During seventeen of his twenty-four pro seasons between 1993 and 2016, the standard deviation of his performance off the tee exceeded +1.0; never in that time did it go negative. Since turning forty-two in 2012, however, his average Strokes Gained score has turned slightly negative. Since we’ve already affirmed that age is hell, this may not come as a surprise. Most of Mickelson’s average 1.11 Strokes Gained advantage since 2012 has come on the green (0.44) or in his approach shots (0.43).

Mickelson in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2001 Masters |

3rd |

275 |

–1.69 |

|

2001 U.S. Open |

T-7 |

282 |

–1.28 |

|

2001 PGA |

2nd |

266 |

–2.64 |

|

2002 Masters |

3rd |

280 |

–1.76 |

|

2002 U.S. Open |

2nd |

280 |

–2.21 |

|

2003 Masters |

3rd |

283 |

–1.81 |

|

2004 Masters |

1st |

279 |

–2.10 |

|

2004 U.S. Open |

2nd |

278 |

–2.36 |

|

2004 British Open |

3rd |

275 |

–2.14 |

|

2005 PGA |

1st |

276 |

–1.98 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.00. Effective stroke average: 69.03.

Mickelson’s Career Record (1993–Present)

- Masters: 24 starts, 3 wins (2004, 2006, 2010), –14.22

- U.S. Open: 22 starts, 0 wins, –6.80

- British Open: 21 starts, 1 win (2013), +4.40

- PGA: 24 starts, 1 win (2005), –7.14

- Total (91 starts): –23.76

Se Ri Pak

Almost without exception, Asian players at the top of modern LPGA leader boards cite Pak as the role model spurring them to greatness.

It couldn’t have been easy for Pak, the only Korean on tour when she arrived as a twenty-year-old rookie who spoke little English in 1998. She had one thing going for her: a work ethic. Growing up in Korea, her routine had consisted of rising every day at five thirty and then running up and down the fifteen flights of stairs in her apartment building, forward and backward. That was followed by winter and summer daylong sessions at the driving range.1 The discipline soon helped her fashion an impressive résumé that included six victories on the LPGA of Korea tour.

Her initial efforts on the U.S. tour were undistinguished: a tie for thirteenth in her first competition, a missed cut, and a few finishes in the mid-40s. Pak arrived at the McDonald’s LPGA Championship that May having won about $40,000 in nine starts, putting her on nobody’s radar screen as a contender.

Yet an opening-round 65, followed with two more rounds in the 60s, led to an 11-under-par finish, 3 shots clear of the field.

That victory was initially looked upon as a fluke, in part because Pak followed it with finishes no higher than twenty-sixth in the next four tournaments. For the fifty-third edition of the U.S. Women’s Open July 2 at Blackwolf Run in Wisconsin, Pak was in the familiar position of nameless, faceless part of the pack expected to futilely chase tournament favorites Annika Sorenstam, Laura Davies, and Karrie Webb.

Instead, Pak shot an opening 69 to tie for the first-round lead, followed with a 70, and then held on as Blackwolf Run chewed up the field. Surprisingly, Pak’s toughest challenge came from none of the favorites but from amateur Jenny Chuasiriporn, another twenty-year-old making her first public splash. Playing one group ahead of Pak, Chuasiriporn holed a forty-foot birdie putt on the final hole to tie Pak for the lead and force an eighteen-hole Monday playoff. The two unknowns battled through all eighteen of those holes and more before Pak sank an eighteen-foot birdie putt on the twentieth hole to claim the trophy. She became the youngest woman ever to win the U.S. Open, the youngest ever to win two majors, and an idol in Korea.

Her stunning debut—victories in the first two majors in which she competed—made Pak the obvious choice as Tour Rookie of the Year, and with more than $870,000 in official winnings she finished second on the money list behind only Sorenstam. Pak followed up with a victory in the 2001 Women’s British Open and added a second LPGA title in 2002 and a third in 2006, defeating Webb in a playoff. By 2007 she had qualified for induction into the World Golf Hall of fame; she was just twenty-nine, the youngest honoree in the hall’s history.

Pak’s most profound legacy—the hordes of young Asian players who modeled their games after her—was just starting to show itself. Those players included Inbee Park and Na Yeon Choi, both of whom cited Pak as their inspiration. At the 2007 U.S. Open, when Pak and Park tied for fourth place, her Asian-born prodigies claimed thirteen of the top-twenty-one placings. By then the tour had a generic name for them: Se Ri’s Kids.

In her prime, Pak’s game was a template for success on the LPGA Tour. Between 1998 and 2002—her peak seasons—Pak averaged 255 yards off the tee, 1.45 standard deviations (14 yards) longer than her competitors. She also hit greens at a 71 percent rate, 1.7 standard deviations (9 percentage points) better than the LPGA field. As she aged, Pak’s advantages in those two areas shrank to about half their peak sizes, although they never evaporated entirely. What did evaporate was Pak’s ability to find the fairway. Between 1998 and 2003, the standard deviation of Pak’s accuracy with the driver was +0.11; from 2004 onward it was –0.76.

Pak largely scaled back her competitive schedule after 2014. Yet by inspiring her fellow Koreans to LPGA success, Pak’s contribution extended far beyond the course. In a 2008 review of her career to that date, Eric Adelson said Pak “changed the face of golf even more than . . . Woods.”2

Pak in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1998 LPGA |

1st |

273 |

–1.79 |

|

1998 U.S. Open |

1st |

290 |

–2.44 |

|

2000 U.S. Open |

T-15 |

293 |

–1.53 |

|

2000 du Maurier |

T-7 |

289 |

–1.26 |

|

2001 Nabisco |

T-11 |

287 |

–1.15 |

|

2001 U.S. Open |

2nd |

281 |

–1.74 |

|

2001 British Open |

1st |

277 |

–2.05 |

|

2002 U.S. Open |

5th |

285 |

–1.37 |

|

2002 LPGA |

1st |

279 |

–2.77 |

|

2002 British Open |

T-11 |

279 |

–1.22 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.73. Effective stroke average: 69.43.

Pak’s Career Record (1997–Present)

- Kraft Nabisco/ANA: 17 starts, 0 wins, –10.07

- U.S. Open: 19 starts, 1 win (1998), +3.64

- LPGA: 16 starts, 3 wins (1998, 2002, 2007), –0.41

- du Maurier: 3 starts, 0 wins, –2.08

- British Open: 9 starts, 1 win (2001), –5.86

- Evian Masters: 2 starts, 0 wins, –1.23

- Total (66 starts): –14.78

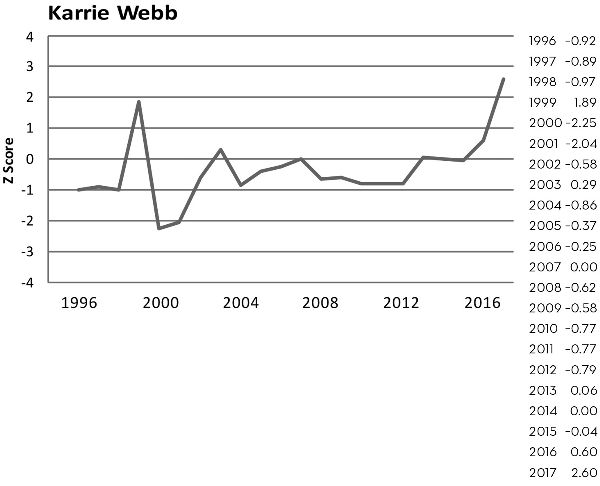

Karrie Webb

Number 6 Peak

Who was the best female golfer of the past twenty years? Don’t jump too quickly to what may seem like the obvious answer . . . at least not until considering the credentials of a talented Australian whose arrival on the LPGA Tour was as impressive as it was meteoric.

For a substantial portion of those years, Karrie Webb may have been better than Annika, Lorena, Inbee, or any other women you can think of. It would be hard to top her debut. A fledgling pro of nineteen making her way on the European women’s tour in July 1994, Webb rocked the British Open with rounds of 69, 70, 69, and 70 to finish 6 strokes ahead of Sorenstam, her closest pursuer.

Despite that victory, the LPGA Tour required Webb to earn her playing card, which she did while playing the qualifying rounds with a broken wrist. She finished second in her American debut, won her next start, and finished second, seventh, fourth, and fifth in the next four. Take that, America. Webb won four times that rookie season, won three more (with four runners-up) as a sophomore, and added two more victories in her third year, 1998. By the time she was twenty-five, she had a second at the du Maurier, a third at the Nabisco, a fourth at the U.S. Open, and a fourth at the LPGA. In 1999 alone, Webb collected six tour titles, finished second another six times, finished in the top five sixteen times in twenty-five starts, and won more than $1.5 million

Between 2000 and 2004, Webb was every bit the match for Sorenstam in her prime. Annika won five majors, but so did Karrie. Annika had seven other finishes in the top five; Karrie had four. Annika had thirteen top-ten finishes in the twenty women’s majors contested during that period; Webb had a dozen.

Webb probably exploded into the American consciousness—which is, after all, what’s important—when she won the highly visible Nabisco tournament (now the ANA Inspiration) by 10 strokes in the spring of 2000. Ten strokes is putting the field to shame, and the performance deserves more than passing mention. Webb’s 274 was 20 strokes below the field average for the week, translating to a –3.77 Z score. In any bell curve set of data, a result 3.77 standard deviations below the norm will occur about one time in a thousand. You can look through all the pages of major tournament competition, and you will find just three golfers who’ve done better: Cristie Kerr, Woods, and Yani Tseng.

She wasn’t done. At that summer’s U.S. Open, Webb staged a second rout, winning this time by 5 strokes over Kerr and Meg Mallon. She tied for second at the 2001 Nabisco—losing to Sorenstam—but made up for it by winning the LPGA by 2. At the 2001 Open, Webb distanced herself from runner-up Se Ri Pak by 8 strokes with a four-round total of 273. This time she produced a –3.24 Z score, the tenth-most-dominant effort in the history of the LPGA Tour. For the eight LPGA majors contested from March 2000 through August 2001, Webb’s average Z score was –2.14.

She claimed her fifth major in three seasons and completed the career Grand Slam, at the 2002 British Open, her margin a mere 2 strokes over Michelle Ellis and Paula Marti.

During her peak seasons—2000 through 2004—Webb’s skill set lacked any gaps. The superiority of her advantages in driver distance, driver accuracy, and greens in regulation all ranged from 1 to 1.9 standard deviation better than the field average; her putting skills registered three-quarters of a standard deviation better than the field. As she aged, Webb’s advantage in length receded; by 2016 the forty-one-year-old was averaging 251 yards off the tee, slightly below the tour average. Yet at that advanced stage of her career, she remained above average in other skill areas, hitting fairways and greens and making putts at rates that were respectively two-thirds, half, and one-quarter of a standard deviation above the tour average.

On the scorecard, Webb declined gracefully. She won the 2006 Kraft Nabisco, defeating Ochoa in a playoff, and lost that season’s LPGA to Pak only in a second playoff. Then in 2007 she lost the LPGA to Suzann Pettersen by one stroke. Since 2007 she has added nine more top-ten major finishes.

Webb in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2000 Nabisco |

1st |

274 |

–3.77 |

|

2000 LPGA |

T-9 |

284 |

–1.40 |

|

2000 U. S. Open |

1st |

282 |

–2.56 |

|

2001 Nabisco |

T-2 |

284 |

–1.62 |

|

2001 LPGA |

1st |

270 |

–2.44 |

|

2001 U.S. Open |

1st |

273 |

–3.24 |

|

2002 LPGA |

T-4 |

285 |

–1.78 |

|

2002 British Open |

1st |

273 |

–2.11 |

|

2003 British Open |

T-3 |

280 |

–1.98 |

|

2004 Kraft Nabisco |

3rd |

279 |

–1.87 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.28. Effective stroke average: 68.62.

Webb’s Career Record (1996–Present)

- Kraft Nabisco/ANA: 22 starts, 2 wins (2000, 2006), –17.57

- U.S. Open: 22 starts, 2 wins (2000, 2001), –0.19

- LPGA: 22 starts, 1 win (2001), –10.13

- du Maurier: 5 starts, 1 win (1999), –3.52

- British Open: 16 starts, 1 win (2001), +3.40

- Evian Masters: 5 starts, 0 wins, +2.88

- Total (92 starts): –25.13

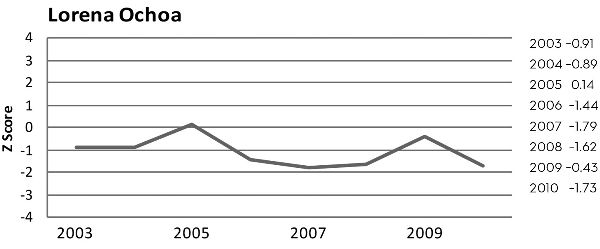

Lorena Ochoa

Lorena Ochoa walked away from tournament golf as close to the height of her ability as it is possible to imagine.

Ochoa competed for seven seasons, plus part of her eighth, before calling it quits in May 2010. She was twenty-eight and less than a month removed from a fourth-place finish in the Kraft Nabisco. But, she said, the constant demands on time and family that the tour imposed had burned her out. “After two or three days of being in Thailand . . . I didn’t want to be out there,” she said, referencing a mid-February tournament halfway around the world from her home in Mexico. “There are so many other things I want to do. I am at peace.”3

So Ochoa retired, committing her efforts to a family-run foundation with a broad focus. Golf is part of it: Ochoa designs courses, operates an instructional academy for youngsters, and sponsors her own tournament. But it doesn’t stop there. The foundation also sponsors an educational center for hundreds of elementary and middle school children near Guadalajara. She has conducted clinics targeted toward senior business executives and has testified in Washington in support of fitness legislation.

It’s an interesting résumé for someone who might, had her heart been driven in a different direction, be thought of today as the greatest female golfer of all time. In retrospect, however, that was never in her grand plan. In fact, a young Ochoa foreshadowed her departure from the scene during a 2002 interview with Golfweek. “I want to be remembered for things I did outside the golf course,” she said at the time. “Not for winning tournaments. That is very clear to me.”4

The product of parents who lived on a golf course and could afford to educate her at a private Mexican school, she early on acquired both a love of golf and a sense of commitment to the needs of her community. Unlike Lee Trevino, Ochoa didn’t need a way out of the barrio; she needed a way to contribute. Golf provided that way. Since arriving on tour full-time in 2003, her success has ratcheted upward. Playing in her first full season, she chased Patrice Meunier-LeBlanc and Annika Sorenstam to the finish at the 2003 Kraft Nabisco, eventually finishing third. She played in two dozen events that first full season and failed to win any of them. But she did earn nearly $825,000.

Ochoa broke through at the 2004 Franklin Morgan Mortgage Championship, although that win could have been viewed as tainted by the absence of several of the tour’s stars, among them Sorenstam. But that victory as well as another later in the season at the Wachovia—combined with nine more top-ten finishes—drove Ochoa’s earnings beyond $1.4 million.

Ochoa won six more times in 2006, positioning herself to supplant Sorenstam as the game’s top player. She picked up nearly $2.6 million in the process. She did not, however, win a major, missing her best chance when Webb beat her in a playoff at the Kraft Nabisco. It took until the final major of 2007, the British Open, for Ochoa to erase that debit mark on her report card, beating Jee Young Lee and Maria Hjorth by 4 shots. Given that it was one of seven Ochoa victories in 2007 alone, and the thirteenth of her professional experience, the prevailing attitude in the galleries was “What took you so long?”

A second major came quickly, the 2008 Kraft Nabisco falling to her by a telling 5 strokes over Sorenstam. Her third-place finish at the LPGA followed a runner-up showing at the 2007 U.S. Open and the British and Kraft Nabisco victories. It also marked her seventh consecutive top-ten finish in a major.

Yet it was already evident to those who looked closely that Ochoa was losing her competitive edge. In 2009, for the first time since she turned pro, Ochoa failed to record a top-ten finish in any of the majors. Her official winnings, more than $4.6 million in 2007, fell to $2.7 million in 2008 and then to $1.5 million. To outward appearances, her fourth-place finish in the 2010 Kraft Nabisco looked like the old Ochoa, but Lorena had already checked out mentally.

The on-course résumé she walked away from needs no burnishing. Nonetheless, a glance at the correlatable skills data is enlightening. Between 2004 and 2008, Ochoa averaged 267 yards off the tee, 2 standard deviations (19 yards, or two clubs) superior to the field average. She hit greens at a 73 percent rate, another 2 standard deviations (9 percentage points) superior to the field. Her putting measured 1.14 standard deviations better than her competitors. As became evident on the scoreboard, that constituted a tough skill set to beat. Ochoa’s average annual Z score in the majors only once exceeded 0. As for additional honors, Ochoa simply did not feel the need to chase them.

Ochoa in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2004 British Open |

4th |

276 |

–1.48 |

|

2006 Kraft Nabisco |

2nd |

279 |

–2.27 |

|

2006 LPGA |

T-9 |

283 |

–1.41 |

|

2006 British Open |

T-4 |

285 |

–1.71 |

|

2007 LPGA |

T-6 |

280 |

–1.41 |

|

2007 U.S. Open |

T-2 |

281 |

–2.05 |

|

2007 British Open |

1st |

287 |

–2.43 |

|

2008 Kraft Nabisco |

1st |

277 |

–2.98 |

|

2008 LPGA |

T-3 |

277 |

–1.81 |

|

2008 British Open |

T-7 |

277 |

–1.30 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.89. Effective stroke average: 69.19.

Ochoa’s Career Record (2003–10)

- Kraft Nabisco: 8 starts, 1 win (2008), –12.29

- U.S. Open: 7 starts, 0 wins, –4.45

- LPGA: 7 starts, 0 wins, –8.40

- British Open: 7 starts, 1 win (2007), –4.05

- Total (29 starts): –29.18

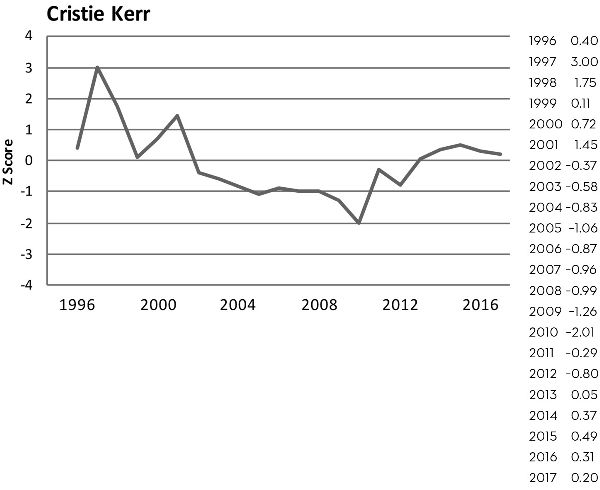

Cristie Kerr

Number 18 Peak

During one astonishing week in 2010, Cristie Kerr authored the most dominant performance in the history of major tournament golf, men’s or women’s.

That June Kerr played the Locust Hill Golf Club in Rochester, New York, site of the LPGA, in rounds of 68-66-69-66 for a winning total of 269. That colorless description does not approach doing justice to Kerr’s feat. She not only won her second major championship and the $337,500 that went along with the trophy but also defeated her closest pursuer by a dozen strokes.

Not that the 6,506-yard course was in lay-down mode that week—at least not for most of the competitors. Among the seventy-three who completed four rounds, the stroke average was 290.99, about 3 over par. Only thirteen managed to break the par of 288, and only four finished as many as 5 strokes below par. Kerr came home at –19.

Kerr failed to post the day’s low round every day of the tournament only because Morgan Pressel managed a Saturday 68, 1 stroke better than her. She needed only 92 percent of the field average number of strokes and, perhaps as remarkably, needed just 96 percent of runner-up Song-Hee Kim’s total. She beat Kim by as wide a margin as Kim beat the tournament’s forty-seventh-place finisher.

It all translated to a Z score of –4.21, the best in the nearly 160-year history of the majors. Tiger Woods may have separated himself from the field at Pebble Beach in 2000, but even he only managed a –4.12 Z score. When Jack Nicklaus played the game with which Bobby Jones “was not familiar” at the 1965 Masters, his Z score only reached –3.50. Kerr’s showing was so remarkable that as early as the morning of the final round, her chief competitors had done something they almost never do in major events: they had given up. “Forget about [Kerr], she’s too far ahead,” remarked eventual runner-up Song Hee Kim of her Sunday game plan.5

A thirty-two-year-old veteran who joined the tour in 1996, Kerr had struggled through six largely unremarkable seasons—a runner-up showing at the 2000 Open being the highlight—before finding her game in 2003. Kerr beat the field average in all four of that season’s majors, winning a personal-best $86,000. Her first trophy came in 2004—the Takefuji Classic, followed by the Shoprite and State Farm—and her earnings rose again, this time to $115,000. A tie for third at the 2005 Kraft Nabisco preceded top tens in the Women’s Open and British Open.

It all constituted a decent turnaround to that point, but Kerr had yet to hit her stride. That occurred with her 2-stroke victory over Angela Park in the 2007 U.S. Open. She finished sixth on the money list that season, tenth in 2008, second in 2009, and third in 2010.

Even setting aside her performance at the LPGA, 2010 was Kerr’s pinnacle season. Her twenty-one starts included two victories, nine top fives, and two other top tens. She tied for fifth at both the Kraft Nabisco and the British Open. Her average Z score in that season’s four majors was –2.01, the best on the women’s tour for the second consecutive season.

Kerr was thirty-nine at the end of the 2017 season—old by LPGA standards but not debilitatingly so. Indeed, her correlatable skills had not by that point deteriorated. This may be because Kerr was solid but not spectacular in all of those areas. Across her career, she drove the ball at a rate just under 1 standard deviation better than the average, although by 2017 that figure had deteriorated only to 0.4 a standard deviation better. In 2017 she also hit greens at a rate about 0.4 of a standard deviation better than the norm, below her career-long 1.11 standard deviation advantage but still good. She compensated for those declines by enjoying the best putting season of her career, requiring just 28.89 per round. That was fifth best on tour and 1.92 standard deviations better than the tour average, substantially improved from her 0.65 career advantage.

So dominant was Kerr that magical week in Rochester that it inevitably biases her peak rating, although perhaps biases isn’t the correct word; she did, after all, do it. Had Kerr merely won in normal fashion—say, with a –2.0 Z score—her 2007–11 peak rating would today be –1.78. But Kerr did score that unprecedented rout; she did post a –4.21. The result is a peak rating of –2.00, the eighteenth best by any player in the history of major tournament golf.

Kerr in the Clubhouse

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2007 U.S. Open |

1st |

279 |

–2.43 |

|

2008 British Open |

6th |

276 |

–1.48 |

|

2009 Kraft Nabisco |

T-2 |

280 |

–2.04 |

|

2009 U.S. Open |

T-3 |

286 |

–1.70 |

|

2009 British Open |

T-8 |

291 |

–1.20 |

|

2010 Kraft Nabisco |

T-5 |

284 |

–1.40 |

|

2010 LPGA |

1st |

269 |

–4.21 |

|

2010 British Open |

T-5 |

282 |

–1.81 |

|

2011 U.S. Open |

3rd |

283 |

–1.94 |

|

2011 LPGA |

T-3 |

280 |

–1.77 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.00. Effective stroke average: 69.03.

Kerr’s Career Record (1996–Present)

- Kraft Nabisco/ANA: 18 starts, 0 wins, –9.41

- U.S. Open: 21 starts, 1 win (2007), –5.64

- LPGA: 21 starts, 1 win (2010), –2.83

- British Open: 16 starts, 0 wins, –7.17

- du Maurier: 4 starts, 0 wins, +7.28

- Evian Masters: 5 starts, 0 wins, +4.57

- Total (85 starts): –13.20

The top-ten golfers of all time for peak rating as of the end of the 2000 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score | Effective stroke average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Arnold Palmer |

1960–64 |

–2.31 |

68.57 |

|

2. |

Jack Nicklaus |

1971–75 |

–2.302 |

68.59 |

|

3. |

James Braid |

1901–10 |

–2.18 |

68.76 |

|

4. |

Tom Watson |

1977–81 |

–2.17 |

68.78 |

|

5. |

Ben Hogan |

1950–54 |

–2.13 |

68.84 |

|

6. |

Bobby Jones |

1926–30 |

–2.11 |

68.87 |

|

7. |

Walter Hagen |

1923–27 |

–2.10 |

68.88 |

|

8. |

Sam Snead |

1947–51 |

–2.07 |

68.93 |

|

9. |

Mickey Wright |

1958–62 |

–2.06 |

68.94 |

|

10. |

Harry Vardon |

1896–1904 |

–2.03 |

68.98 |

The top-ten golfers of all time for career rating as of the end of the 2000 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Jack Nicklaus |

1962–80 |

–104.55 |

|

2. |

Walter Hagen |

1913–40 |

–73.79 |

|

3. |

Patty Berg |

1935–68 |

–73.21 |

|

4. |

Sam Snead |

1937–62 |

–68.69 |

|

Louise Suggs |

1948–72 |

–60.31 |

|

|

6. |

Mickey Wright |

1954–84 |

–59.67 |

|

7. |

Gene Sarazen |

1920–51 |

–58.09 |

|

8. |

Ben Hogan |

1938–62 |

–53.09 |

|

9. |

Byron Nelson |

1933–60 |

–44.88 |

|

10. |

Jim Barnes |

1913–32 |

–44.58 |

The top-ten golfers of all time for peak rating as of the end of the 2010 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score | Effective stroke average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Tiger Woods |

1998–2002 |

–2.60 |

68.15 |

|

2. |

Annika Sorenstam |

2002–6 |

–2.49 |

68.31 |

|

3. |

Arnold Palmer |

1960–64 |

–2.31 |

68.57 |

|

4. |

Jack Nicklaus |

1971–75 |

–2.302 |

68.59 |

|

5. |

Karrie Webb |

2000–2004 |

–2.28 |

68.62 |

|

6. |

James Braid |

1901–10 |

–2.18 |

68.76 |

|

7. |

Tom Watson |

1977–81 |

–2.17 |

68.78 |

|

8. |

Ben Hogan |

1950–54 |

–2.13 |

68.84 |

|

9. |

Bobby Jones |

1926–30 |

–2.11 |

68.87 |

|

10. |

Walter Hagen |

1923–27 |

–2.10 |

68.88 |

The top-ten golfers of all time for career rating as of the end of the 2010 season.

| Rank | Player | Seasons | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. |

Jack Nicklaus |

1962–80 |

–104.86 |

|

2. |

Walter Hagen |

1913–40 |

–73.94 |

|

3. |

Patty Berg |

1935–68 |

–73.21 |

|

4. |

Tiger Woods |

1996–2010 |

–71.91 |

|

5. |

Sam Snead |

1937–62 |

–68.69 |

|

6. |

Louise Suggs |

1948–72 |

–60.31 |

|

7. |

Mickey Wright |

1954–84 |

–59.67 |

|

8. |

Annika Sorenstam |

1994–08 |

–59.16 |

|

9. |

Gene Sarazen |

1920–51 |

–58.09 |

|

10. |

Ben Hogan |

1938–62 |

–53.09 |