12

Still on the Course

Something has happened to the face of the best professional golfers since the emergence of Tiger Woods. It has gotten younger. For three decades, roughly between 1970 and 2000, experience counted heavily on both the men’s and the women’s professional circuits. Not so much anymore.

A study of the prime performance period of the best PGA and LPGA pros shows a clear pattern. For decades, as both tours matured, the ages at which the game’s greatest reached their peak declined. The decline has been slow but inexorable. If we group the approximately two hundred players whose careers were examined for this book generationally, the trend is clear.

The peaks of twenty-four occurred prior to 1920. The average age of those twenty-four at midpeak was 30.5 years. Between 1920 and the end of World War II, another twenty-six players peaked. Their average age at mid-peak was 30.8 years . . . not substantially different.

From 1946 through the 1950s, the average age of the twenty-five most successful players rose, to 34.8 years. But this was an aberration, created in some measure by World War II—which probably postponed the primes of Snead, Hogan, and Mangrum—and also by the emergence of the women’s tour. Patty Berg, to name one, hit stardom at an older than usual age because there had been no stardom to hit a decade earlier. In any event, the average reverted to 31.4 years for forty stars whose midprimes occurred during the 1960s and 1970s. During the 1980s and 1990s, forty-two stars hit midprime, and they did so at an average age of 34.0 years.

The arrivals of Woods and Se Ri Pak, just 20 when she came out of nowhere to win the U.S. Open and LPGA in 1998, appear to have marked turning points on both tours. Since 2000 forty-four of the game’s most dominant men and women have entered primes. The average age at prime of those forty-four was just 27.1 years, a full 7 years younger than the parallel group from the 1980s and 1990s. Among those forty-four, the primes of twenty-six have begun since 2010; their average age is just 25.9 years. That precocious list includes Jordan Spieth, Jason Day, Lydia Ko, Inbee Park, and Rory McIlroy.

The genius Tiger Woods showed at such an early age is almost taken for granted today. He was 22 years old when he entered into the best five-season stretch of his career in 1998, and perhaps some perspective is in order on that fact. Prior to Woods, the last nine true PGA Tour stars—Vijay Singh, Paul Azinger, Davis Love, Nick Price, Greg Norman, Nick Faldo, Ian Woosnam, José María Olazábal, and Payne Stewart—were all 30 or older when they hit their prime performance periods. No player had done so before age 25 since Ben Crenshaw, who was 24 when his prime began in 1976. In all of golf history, only thirteen stars—men or women—entered their primes before age 21. Eight of those thirteen began their golfing maturity within the most recent two decades and six within the most recent decade. That poses a tantalizing question: Are we now passing through the greatest era of golfing talent in the measurable history of the game?

If by that question we seek to measure the cumulative peak performances of the stars, the answer might be yes. Woods (number 1 all time in peak rating), Sorenstam (number 2), Tseng (number 5), and Webb (number 6) give the current or recently retired generation four players in the top seven.

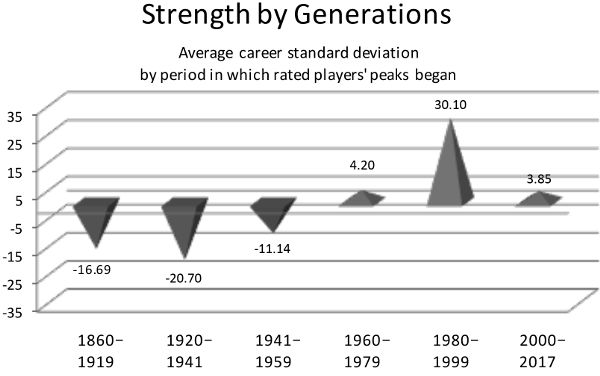

One way to get a feel for whether any particular generation of star players was superior to others is to calculate the average peak Z score of each “generation” of the game’s greats based on the midpoint of their peaks. We can easily do that for the players on whose records this book is based. The results graph as follows.

The data illustrate that at least in terms of the top-ranked players, the present crop may indeed represent the apex of superstardom on the links. At –1.51, the average peak Z score of the modern players included in the ranking represents the best performance of any generation. And since some of those modern stars remain in their peaks, they could still improve on that average.

One clear implication of the peak-score graph is that stars are stars in any generation. With the exception of pre-1920 stars, the average peak Z scores for all generations don’t vary by much.

The present generation is nowhere near tops for producing career value. With an average career Z score of –20.70, that honor rests with the dominant players who reached the physical prime between the world wars. In fact, the average career Z scores of all generations since 1960 are positive. Why? The answer is likely money. With far richer pots to play for, modern-era players are hanging around several years after their predecessors packed it up and went home. In doing so, they are making big bucks but also driving their career Z scores from exceptional toward average.

Here’s a graph of the career performance totals by decade.

A second factor influencing the career totals of all players is the raw number of tournaments played. Unlike peak value, which in most cases represents the 10 best tournaments from a player’s defined five-season peak period, career totals are cumulative and poor results are counted. For the game’s early stars, it’s virtually impossible to build up substantial career totals. Together, Old Tom and Young Tom Morris only played in 20 major tournaments (excluding those Old Tom played in when he was past his prime). That’s only about one-quarter Tiger Woods’s total and fewer than a fifth of Jack Nicklaus’s total.

Most of the modern pros, however—those who aren’t Tiger or Jack—have the opposite problem. Nick Faldo is a good example. Between 1976 and 2006—his functional career—Faldo teed it up in 93 majors. He did pretty well, too, winning 6 of them, placing second in 2 others, and landing 24 top 10s. But Faldo also missed 18 cuts, and those undermined his career Z score by about 3 points per missed cut. Like a lot of his compatriots, the lure of large paydays caused Faldo to stay at the party long enough to damage his career rating. Fifteen of his 18 missed cuts came when Faldo was in his forties. In fact, if Faldo was scored solely on his career accomplishments between 1983 and 1996, he’d be among the top thirty all time for career performance, at –32.18. Instead, his career rating is +7.32.

Let us not leave the impression that playing in a lot of majors is and always must be a bad thing. Jack Nicklaus played in 111 of them between 1962 and 1989, and he leads the career list. As with life itself, the number of opportunities is less important than what one makes of them.

Could anyone playing today eventually surpass Tiger on the peak-value list or Jack in career value?

The easy emotional answer is “Sure, that could happen.” Several emerging talents could do it. Rory McIlroy, Jordan Spieth, Jason Day, and Dustin Johnson are all candidates. But the emotional answer is, of course, not always the proper answer. Woods set a monumental standard between 1998 and 2002. The fact that he leads players of the stature of Sorenstam, Palmer, and Nicklaus should give fans of Spieth, McIlroy, and a cohort of women pause.

Let’s look at each of the peak and career scores through 2017 of several modern male and female stars.

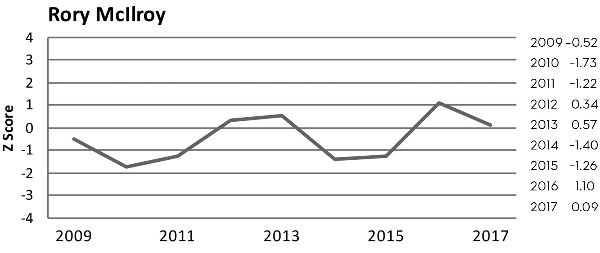

Rory McIlroy

McIlroy functionally arrived in 2009, announcing his presence by tying for third at the PGA. That was the tournament when Y. E. Yang famously de-pantsed Tiger by 3 shots. But McIlroy’s true peak period began in 2011 with his dominating victory in the U.S. Open. That 8-stroke win at Congressional translated to a Z score of –3.07. His win at the 2012 PGA—again by 8 strokes—brought another minus –3 Z score. McIlroy’s two 2014 victories at the British Open and PGA were less dominant but still generated Z scores in the range of –2.0 and –2.4. The 2015 season brought top-ten finishes in the Masters and U.S. Open.

Four scores of –2.0 or lower in five years constitutes a pretty good start toward a memorable peak Z score. But McIlroy’s performances in other tournaments have been only marginally as impressive. Among his ten best tournaments between 2011 and 2015 were also a tie for twenty-third in the 2014 U.S. Open and seventeenth at the 2015 PGA. In 2016 he mixed top tens at the Masters and British Open with missed cuts at the U.S. Open and PGA, offsetting that—in his bank account, if not his Z score—by winning the FedEx Cup. His average score in the eight 2016–17 majors is a pedestrian +0.60, including three missed cuts. With that uneven record, McIlroy failed to improve his five-year peak from its 2011–15 average of –1.66.

Given the mediocrity of McIlroy’s 2016 and 2017, he would need to average about –1.75 through the 2018 season in order to improve his peak rating. The math varies, but generally a –1.75 score translates to a top-three finish. So what are the odds of McIlroy finishing among the top three in four consecutive majors?

There are three methods of speculating on future performance: past performance, historical comparables, and statistical projections. Unfortunately, none of them is notably reliable. For whatever they are worth, two can easily be applied to McIlroy.

Aside from his four championships, entering 2018 McIlroy has not produced a –1.75 score. McIlroy’s five-year forecast tells the same tale. It projects average annual Z scores on the mediocre side of average. In short, Rory is a significantly less viable candidate for climbing the peak-rating ladder than he was a couple of years ago.

The same can be said of his prospects for advancing on the career-rating chart. Through the 2017 season, it stands at –10.19, well outside the top thirty. Two years ago, however, McIlroy’s career score was –14.94. Those three intervening missed cuts are something dominant players are not supposed to do. Prior to his inauspicious 2016–17 stretch, McIlroy had been averaging about –3.00 per season, meaning that in the event he regains his prior form and plays consistently over the next decade, he could expect to improve his career score by about 30 points. If that occurs, McIlroy would probably find himself ranked among the top fifteen all time. That, however, is something beyond difficult, as his performance at the 2018 Masters demonstrates. He placed fifth, but produced only a –1.28 Z score. His forecast suggests that McIlroy is likely to add to, not subtract from, his career total in the near future. Simply put, McIlroy has not shown the consistency needed to gain traction on the career-rating list: the ability, yes; the consistency, no.

McIlroy’s strength has always been off the tee. Since first playing enough PGA Tour events to generate a qualifying statistical base in 2010, McIlroy’s Strokes Gained rating off the tee has averaged 1.02. That’s more than half of his overall 1.88 average Strokes Gained. His weaknesses—perhaps mediocrities is a better qualifier—intensify the closer he gets to the hole. All four of McIlroy’s career Strokes Gained measurements are technically positive, but his measurements around and on the green are both only marginally so. He generates less than one-fifth of a stroke advantage—compared with average players—on and around the green.

Here’s how McIlroy’s peak scorecard looks at the moment.

McIlroy to Date

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2011 U.S. Open |

1st |

268 |

–3.07 |

|

2012 PGA |

1st |

275 |

–3.02 |

|

2013 PGA |

T-8 |

277 |

–1.13 |

|

2014 Masters |

T-8 |

288 |

–0.75 |

|

2014 U.S. Open |

T-23 |

286 |

–0.34 |

|

2014 British Open |

1st |

271 |

–2.40 |

|

2014 PGA |

1st |

268 |

–2.09 |

|

4th |

276 |

–1.72 |

|

|

2015 U.S. Open |

T-9 |

280 |

–1.14 |

|

2015 PGA |

17 |

279 |

–0.93 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.66. Effective stroke average: 69.53.

McIlroy’s Career Record (2009–Present)

- Masters: 8 starts, 0 wins, –4.48

- U.S. Open: 8 starts, 1 win (2011), +4.88

- British Open: 8 starts, 1 win (2014), –2.70

- PGA: 8 starts, 2 wins (2012, 2014), –7.89

- Total (32 starts): –10.19

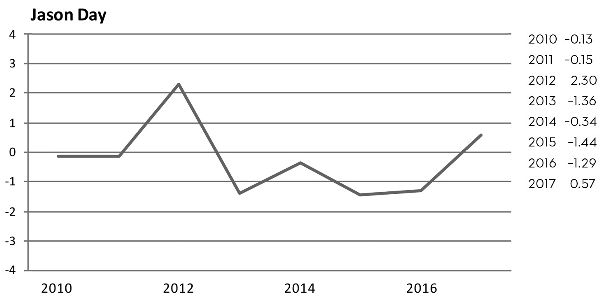

Jason Day

A superb 2015 season—victory at the PGA coupled with top tens at the U.S. and British Opens—propelled Day into the front rank of contemporary male players. A solid 2016 that included top tens in three majors led to the world number 1 rank. Beyond that, his peak rating of –1.66 entering 2017 left room to grow, since none of his ten best scores from that period came during 2012.

More than any other current young player with the possible exception of Jordan Spieth, it was fair to play the peak-value speculation game with Jason Day when he entered 2017 on the heels of four solid seasons—ten top tens in sixteen major starts. Had he maintained that performance level, his peak rating would by year’s end have improved from 1.67 to –1.80, right at the fringe of the top twenty-five all time. And he would have done so before age thirty, when most successful tour pros historically hit their stride.

To the extent that was ever a realistic forecast, it certainly is not now. It must be left to the swing analysts—or possibly the medics—to ascertain the reasons behind Day’s 2017 slide. A missed cut in the U.S. Open was not fully offset by modest midpack finishes at the Masters, British Open, and PGA, the whole constituting a season that did not move Day’s peak-performance needle. For a twentysomething aspiring to be counted among the greats, this is a bad trend. Compare the change between Day’s ages twenty-eight and twenty-nine seasons with the same chronological seasons of the best of previous generations:

| Player | Age 28–29 seasons | Age 28 average Score | Age 29 average Score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Jason Day |

2016–17 |

–1.29 |

+0.57 |

|

Tiger Woods |

2004–05 |

–0.60 |

–2.28 |

|

Greg Norman |

1983–84 |

+0.11 |

–0.86 |

|

Jack Nicklaus |

1968–69 |

–0.61 |

–0.72 |

|

Arnold Palmer |

1958–59 |

–0.48 |

–1.24 |

|

Sam Snead |

1940–41 |

–0.68 |

–0.21 |

|

Ben Hogan |

1940–41 |

–0.68 |

–1.51 |

|

Byron Nelson |

1940–41 |

–1.43 |

–1.24 |

|

Gene Sarazen |

1930–31 |

–1.30 |

–1.45 |

|

Walter Hagen |

1921–22 |

–2.00 |

–1.85 |

|

Average |

–0.95 |

–1.08 |

If he aspires to be counted among the game’s greats, plainly Day’s career path took an ill-advised U-turn in 2017. Only a couple of those greats declined at all between their ages twenty-eight and twenty-nine seasons, and when they did—note Nelson and Hagen—it was a coincidental decline off a substantial season. Day’s average Z score worsened by 1.87 between 2016 and 2017. In major professional golf, nothing is irreparable, but a turnaround from that sort of midcareer decline would be unprecedented.

His performance during 2017 also calls into question the future of Day’s career rating. Here’s the impact one season can have on projected future performance. As of the end of 2016, we would have said that had Day continued his performance pattern through 2022, his career value would have been about –47. At that level, he would be closing in on the all-time top ten. But 2017 substantially altered that projection. As of the end of 2017, Day projected to conclude 2022 with a career score around –27, making him the modern equivalent of Leo Diegel (–25.02). There is nothing wrong with emulating the career record of Diegel, the 1928–29 PGA Championship winner. But chasing Diegel is a far cry from chasing Nicklaus. And beyond that, Day’s 2017 performance was so removed from his established pattern that it’s hard to know whether to consider it an anomaly or a new normal. If the latter, then even Leo Diegel is out of reach.

Day’s projection does at least offer this much solace. It continues negative, which is good, although not nearly at the same rate, yielding average Z scores in the –0.8 range. That, too, is Leo Diegel territory.

The Strokes Gained data provide another illustration of Day’s decline. Here are his slash lines for his peak seasons:

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Off the tee |

0.45 |

0.50 |

0.77 |

0.19 |

0.33 |

0.34 |

|

Approaching |

0.01 |

0.18 |

0.46 |

0.43 |

–0.25 |

0.07 |

|

Around green |

0.17 |

0.40 |

0.29 |

0.38 |

0.32 |

0.23 |

|

Putting |

0.37 |

0.32 |

0.59 |

1.13 |

0.33 |

0.46 |

|

Total |

1.00 |

1.40 |

2.11 |

2.13 |

0.73 |

Comparing 2015 and 2016 with 2017, note particularly the sharp performance decline in Day’s play approaching and on the green. Recall that an average pro’s performance approaching the green correlates to his score at a 60 to 70 percent level during those seasons. Given that his 1.13 2016 Strokes Gained putting performance represents an aberration from his norm, perhaps the 0.8 of a stroke fallback in that category he sustained in 2017 represents to some degree a reversion to the norm. His overall play, however, shows a more alarming pattern. His total Strokes Gained numbers arced on what we might think of as a normal “star” pattern through the first four seasons of his prime, from 1.00 to 1.40 to 2.11 and then to 2.13. Not yet thirty in 2017, there was every reason to anticipate at least a minimal climb to 2.15, which would have put his stroke average at approximately 68.78, the best on tour and fractionally better than Jordan Spieth. Instead, he averaged 70.12 strokes, twenty-fourth best. His closest comparable was Daniel Berger. Daniel Berger is a nice player, and he had a nice season in 2017. But nobody counts him among the game’s all-timers.

Here is Day’s rating through 2017.

Day to Date

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2013 Masters |

3rd |

281 |

–1.93 |

|

2013 U.S. Open |

T-2 |

283 |

–1.80 |

|

2013 PGA |

T-8 |

277 |

–1.13 |

|

2014 U.S. Open |

T-4 |

281 |

–1.16 |

|

2015 U.S. Open |

T-9 |

280 |

–1.14 |

|

2015 British Open |

T-4 |

274 |

–2.19 |

|

2015 PGA |

1st |

268 |

–2.70 |

|

2016 Masters |

T-10 |

289 |

–1.05 |

|

2016 U.S. Open |

T-8 |

282 |

–1.16 |

|

2016 PGA |

2nd |

267 |

–2.44 |

Note: Average Z score: –1.67. Effective stroke average: 69.51.

Day’s Career Record (2010–Present)

- Masters: 6 starts, 0 wins, –5.23

- U.S. Open: 7 starts, 0 wins, –2.47

- British Open: 7 starts, 0 wins, +1.50

- PGA: 8 starts, 1 win (2015), –5.66

- Total (28 starts): –11.87

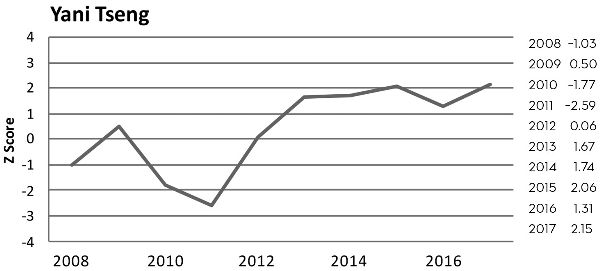

Yani Tseng

Number 5 Peak

Whatever became of Yani Tseng?

There appeared to be no limit to Tseng’s ability when the Taiwanese teen defeated Maria Hjorth to win the 2008 LPGA Championship. Tseng followed that with 2010 victories at the Kraft Nabisco and British Open and then in 2011 put together the most dominant season in the history of women’s major tournament competition. Tseng finished a strong second at the Kraft Nabisco, lapped the LPGA field by 10 strokes, and won the British Open by 4. Combined with a fifteenth-place finish in the U.S. Open, her –2.59 average Z score has been surpassed only by Tiger Woods (–2.77 in 2000).

In that context, Tseng’s third-place finish at the 2012 Kraft Nabisco, the season’s first major, looked like nothing out of the ordinary. It brought her peak Z score to –2.31, the fifth best of all time, and positioned her to threaten Woods, Sorenstam, Nicklaus, and Palmer for the top four spots. Since then, all of Tseng’s momentum has evaporated. She has managed only two top-twenty-five finishes in the twenty-seven ensuing majors through 2017 and missed the cut in fifteen. Her scoring average, 69.66 strokes in 2011, rose to 71.12 in 2012, then to 71.71, 72.19 in 2014, 72.05 in 2015, and 73.47 in 2016. If one were to recalculate her peak score for the 2012–16 period, it would be +0.14, and there be no reason to be discussing Yani Tseng. Tseng’s cumulative Z score for the twenty women’s majors contested since 2013 is +42.53.

To date, nobody’s come up with a good explanation for why the decline has occurred. If one examines the correlative data, the answer may lay in Tseng’s ability to hit greens in regulation. During her peak seasons—2008 through 2012—Tseng hit greens at a rate nearly a full standard deviation better than her fellow competitors. Since 2013 she has hit greens at a rate nearly a half standard deviation worse than her competitors. On a tour with a consistent 80 percent correlation between hitting greens in regulation and scoring, that’s a recipe for mediocrity. Having noted that, Tseng remains active, and as of 2017 she was only twenty-eight. So it’s possible this is one of those Jack Nicklaus things—a marvelous young peak, followed by a relative decline, followed by an even greater peak, which in Tseng’s case might begin next season, or five seasons from now.

If not, well, she’ll always have 2008–12.

Tseng to Date

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2008 LPGA |

1st |

276 |

–2.01 |

|

2008 British Open |

2nd |

273 |

–2.02 |

|

2009 Kraft Nabisco |

T-17 |

288 |

–0.80 |

|

2010 Kraft Nabisco |

1st |

275 |

–2.91 |

|

2010 U.S. Open |

T-10 |

290 |

–1.03 |

|

2010 British Open |

1st |

277 |

–2.77 |

|

2011 Kraft Nabisco |

2nd |

278 |

–2.70 |

|

2011 LPGA |

1st |

269 |

–4.10 |

|

2011 British Open |

1st |

272 |

–2.83 |

|

2012 Kraft Nabisco |

3rd |

280 |

–1.73 |

Note: Average Z score: –2.29. Effective stroke average: 68.60.

Tseng’s Career Record (2008–Present)

- Kraft Nabisco/ANA: 10 starts, 1 win (2010), +2.78

- U.S. Open: 9 starts, 0 wins, +6.54

- Women’s PGA: 10 starts, 2 wins (2008, 2011), +4.87

- British Open: 10 starts, 2 wins (2010, 2011), –2.91

- Evian Masters: 5 starts, 0 wins, +11.95

- Total (44 starts): +23.23

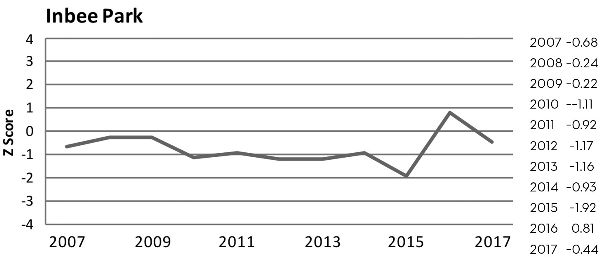

Inbee Park

Number 20 Peak, Number 21 Career

Since Annika Sorenstam’s retirement, the LPGA Tour has run through a series of briefly dominant players, none able or willing to rise to Sorenstam’s level of performance for a lengthy stretch. From 2004 through 2008, Lorena Ochoa won two majors and finished in the top ten in fifteen. But in 2010, not yet thirty, she abruptly left the tour to pursue personal goals. The vacuum created by Ochoa’s absence was quickly filled by Yani Tseng, who was brilliant for two seasons only to abruptly go AWOL from the leaderboard.

Then up stepped Inbee Park.

There are many similarities between Ochoa, Tseng, and Park. All three are foreign born—Park is from Korea—and all were in their early twenties when they arrived as stars. Ochoa and Tseng both functionally disappeared before age thirty. Park was twenty-nine in 2017.

Starting with her emergence in 2011, Park had five seasons among the LPGA’s leaders, and her victories at the 2014 and 2015 LPGA, the 2015 British Open, and the 2016 Rio Olympics suggest she’s not going anywhere soon. But her injury-plagued performances in 2016 and 2017 argue otherwise. Following a perfectly credible tie for sixth at the 2016 ANA Inspiration, Park missed her first major cut in eight seasons at the Women’s PGA and then fought a hand injury that sidelined her for the remainder of the pro season. In 2017 she missed a fourth major of her last eight—the Evian Masters—and failed to make the cut at the U.S. Open. Beyond that, there has been speculation that Park may imitate Ochoa in another meaningful way: leaving the tour in a year or so to concentrate on her family.

In her 2016 absence, a veritable host of potential new stars divided the spoils: Brooke Henderson at the Women’s PGA, Brittany Lang at the U.S. Open, Ariya Jutanugarn at the British Open, and In Gee Chun at the Evian. They along with Lydia Ko, nineteen, and Lexi Thompson, twenty-one, are not in awe of what Park accomplished when they were in high school.

Park knows that feeling. She turned pro in 2007, when she was nineteen. Her career score through 2017 is –36.80, heady stuff for a woman in her twenties. At a comparable stage of his career, Jack Nicklaus’s career score was –27.60.

On the other hand, Nicklaus accumulated –71.06 career Z score points between twenty-nine and forty, an age when the best women pros of the past two decades—Sorenstam, Ochoa, Pak—have not kept pace. Park’s 2016 and 2017 cumulative scores have been easily her two worst since 2009. Her five-year projection is consistent but only modestly negative, yielding annual Z scores that hang around –0.50. That would improve her career rating to about –47 by 2022. But the forecast does assume something not necessarily in evidence, namely, that Park maintains her 2014–17 form rather than her 2016–17 form. Those are two different things. Her playoff loss at the 2018 ANA Inspiration, which generated a –1.88 Z score, gave fans some reason for hope. Still, it would take a level of faith in Inbee Park ascribable only to her own mother to imagine her challenging Nicklaus’s career standard.

The correlatables continue to portray Park as one of the tour’s masters of the precision game. In 2017 she hit 73 percent of greens, 1 standard deviation better than the 68 percent tour average. She needed just 28.94 putts per round, sixth best overall and 1.8 standard deviations better than the 29.9 field average. Her driving stats have never ranged far outside the LPGA norm.

Following are Inbee Park’s peak and career charts to date.

Park to Date

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2013 LPGA |

1st |

283 |

–1.75 |

|

2013 U.S. Open |

1st |

280 |

–2.77 |

|

2014 LPGA |

1st |

277 |

–2.46 |

|

2014 British Open |

1st |

276 |

–1.65 |

|

2015 LPGA |

1st |

273 |

–3.20 |

|

2015 U.S. Open |

T-3 |

275 |

–1.72 |

|

2015 British Open |

1st |

276 |

–2.59 |

|

2015 Evian Masters |

T-8 |

279 |

–1.18 |

|

2016 ANA Inspiration |

T-6 |

280 |

-1.23 |

|

2017 ANA Inspiration |

T-3 |

275 |

–2.07 |

|

2017 LPGA |

T-7 |

277 |

–1.26 |

Note: Average Z score:–1.99. Effective stroke average: 69.04.

Park’s Career Record (2007–Present)

- Kraft Nabisco/ANA: 10 starts, 1 win (2013), –9.06

- U.S. Open: 10 starts, 2 wins (2008, 2013), –9.87

- Women’s PGA: 11 starts, 3 wins (2013, 2014, 2015), –8.88

- British Open: 10 starts, 1 win (2015), –8.17

- Evian Masters: 3 starts, 0 wins, –0.83

- Total (44 starts): –36.80

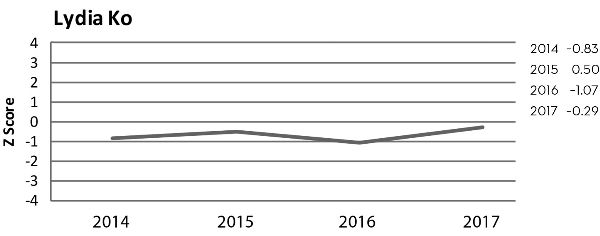

Lydia Ko

Prior to 2017 Lydia Ko was clearly on a path to become one of the dominant personalities in the history of major tournament golf. Having announced her presence while still an amateur by finishing second in the 2013 Evian Masters, she turned pro, won two majors, and added runner-up (at the Women’s PGA) and third-place finishes (at the U.S. Open), all while rising to number 1 in the world.

More, she accomplished all that in her first sixteen professional majors, meaning that her peak rating was only then beginning to gel. It was an impressive one, hitting –1.82, within reach of the all-time top twenty-five.

Her career rating improved concurrently. Ko began accumulating Z scores at the rate of –3.75 per season. Were she to maintain that trend over the next decade, she would have hit –51 by age thirty, a total that would rank eleventh on the all-time career list.

What happened instead cannot be explained . . . at least not by me. Ko only once finished above thirtieth in 2017’s five majors, posting the second- and fourth-worst performances of her still young LPGA career. Her average Z score for the year was –0.29; her average Z score one season earlier had been –1.07.

The experts lined up with theories: she had changed her caddie, she had changed her swing coach, she lacked the same mental intensity, and so on. To the extent the numbers pointed anywhere, they indicted her work on the greens. The tour’s top putter in 2016 (28.31 strokes per round), she fell back to 29.14 putting strokes per round in 2017. That still ranked a solid fifteenth on tour, but it also accounted for all of Ko’s 0.4 of a stroke rise in scoring average—from 69.6 in 2016 to 70.00 in 2017—and then some.

For the normal tour player, there is generally only about a 40 percent correlation between how one putts and how one scores on tour. But perhaps Ko isn’t the normal tour player. Perhaps her so-so standing in the tour’s other measurables requires her to putt extraordinarily well in order to succeed. Her average driving distance, around 244 yards, is about 1 standard deviation below the LPGA norm. Her accuracy is slightly above average . . . but we’ve already demonstrated that accuracy off the tee is the least important measurable skill for any tour pro. The most important skill, particularly for an LPGA pro, is the ability to hit a green in regulation. Ko improved slightly in that respect, from 70 to 72 percent in 2017. Both figures are only slightly better than the tour norm, which hovers around 68 percent.

All of the above may lead us to conclude that Lydia Ko must putt very well to win. But the data only partially support that conclusion, too. When she won the 2015 Evian Masters, Ko ranked fifteenth in the field in putting; that’s good, but hardly dominant. She won that season’s Canadian Pacific while ranking twentieth in putting and won the Swinging Skirts while tying for ninth in skill on the greens.

Ko’s third-place showing in 2017’s final major, the Evian Masters, gives fans reason for hope. Her five-year forecast paints her as a better than average but not standout player, anticipating average annual Z scores in the –0.4 range. Prior to 2017, however, that same projection line would have dipped below –1.0. Her performance on the 2018 tour will tell us a lot about her future. A strong bounce back, and 2017 will be a mere slump. A second consecutive subpar season, and she could become this decade’s Yani Tseng . . . a golfing meteor. Her tie for twentieth at the season’s first major, the ANA Inspiration, produced a –0.52 Z score, very much in line with the projection that she is on her way to becoming part of the field.

Ko to Date

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2014 LPGA |

3rd |

280 |

–1.88 |

|

2014 Evian Masters |

T-8 |

280 |

–1.18 |

|

2015 U.S. Open |

T-12 |

279 |

–0.90 |

|

2015 British Open |

T-3 |

280 |

–1.95 |

|

2015 Evian Masters |

1st |

268 |

–2.91 |

|

2016 ANA |

1st |

276 |

–2.03 |

|

2016 Women’s PGA |

2nd |

278 |

–2.33 |

|

2016 U.S. Open |

T-3 |

284 |

–1.36 |

|

2017 ANA |

T-11 |

281 |

–0.94 |

|

2017 Evian Masters |

T-3 |

205 |

–2.07 |

Note: Average Z score:–1.82. Effective stroke average: 69.29.

Ko’s Career Record (2014–Present)

- ANA Inspiration: 4 starts, 1 win (2016), –2.46

- U.S. Open: 4 starts, 0 wins, –2.96

- Women’s PGA: 4 starts, 0 wins, –0.73

- British Open: 4 starts, 0 wins, –1.40

- Evian Masters: 4 starts, 1 win (2015), –5.84

- Total (20 starts): –13.92

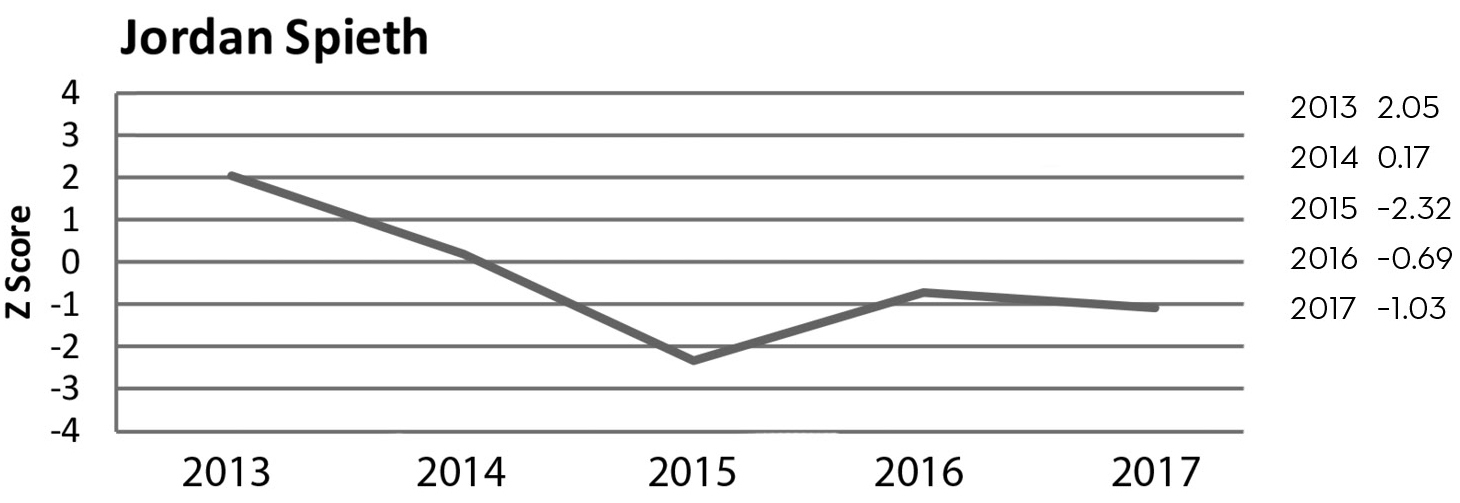

Jordan Spieth

Spieth turned pro in the middle of the 2012 season, but his career path really accelerated in 2015. His victories in the Masters and U.S. Open, coupled with top tens in the other two majors, made him the 2015 player of the year with an average Z score of –2.31 in the majors. Among players who competed in at least three majors, that’s the fourth-best single-season performance in history, exceeded only by Tiger Woods (–2.77 in 2000), Yani Tseng (–2.59 in 201), and Ben Hogan (–2.58 in 1953).

Spieth had competed in nineteen majors as a pro by the end of 2017, compiling a peak rating of –1.82. His record during that time provides ammunition for Spieth lovers, while leaving skeptics a few shreds to which to cling. Jordan’s fans can point to his three major titles, the 2015 Masters and U.S. Open, plus the 2017 British Open. They can also cite his runner-up finishes in the 2015 PGA and 2016 Masters. They can and should note that all of the ten scores constituting his current peak rating were accomplished since April 2014, eight of them since April 2015. That gives him ample room to improve his peak rating during 2018 with no prospect of regression. (He began that process at the Masters with a runner-up finish that translated to a –1.96 Z score.) Finally, they can point to his projection, which sees him generating average Z scores consistently in the range of –1.6 to –2.5 for the near-term future. If he achieves the top end of that scale during any imminent season—the –2.5 end—it would rank with his 2015 among the elite major tournament seasons of all time.

For Spieth, the bottom line is that improvement in his current –1.82 peak is entirely plausible, possibly to the all-time elite levels. It also creates the possibility of Spieth ranking among the career all-time top ten by age thirty. Here’s the bad news for that projection: it’s still just a forecast.

The skeptics have a harder case to make, but they can point out that his British Open victory was Spieth’s only truly exceptional performance since April 2016. They can also note that Spieth finished the 2016 major circuit by tying for thirty-seventh, thirtieth, and thirteenth in the U.S. Open, British Open, and PGA, respectively, and then largely labored through 2017 with three more major performances outside the top ten. To make much of that, of course, they would have to overlook his victory at Royal Birkdale, and to a lesser extent his runner-up finish at the 2018 Masters.

Let’s assume for the sake of argument that Spieth proves his fans right and the skeptics wrong. How high up the peak and career ladder might he realistically be able to ascend? To answer that question, let’s look at a few comparables:

- Peak rating after nineteen professional majors

- Jack Nicklaus –2.24

- Tiger Woods –2.41

- Jordan Spieth –1.82

- Career rating after nineteen professional majors

- Tiger Woods –29.90

- Jack Nicklaus –25.84

- Jordan Spieth –9.28

Okay, Spieth is not (yet) on track to rank with Woods and Nicklaus. Are there better comparables? The answer is: not many. If we consider the field of all PGA pros other than Woods and Nicklaus who established a peak rating better than –1.80 by their twenty-fifth birthdays, and did so within five years of turning pro, that field consists of one name: Spieth. We can expand the qualifiers to age twenty-seven and –1.60, but that only brings in one additional name: Gary Player, who had established a –1.61 peak rating by the end of the 1962 season. Player did eventually raise that rating, but only to –1.62. So going strictly by the admittedly limited number of comparables Spieth generates, it’s possible that his peak rating was already more or less fully formed by 2017.

The same problem presents itself when we look at plausible career comparables. As of the end of 2017, Spieth’s career rating was –9.28. Using our broader criterion of nineteen majors by age twenty-seven, only one close comparable surfaces: Johnny Miller. He had a career rating of –10.03 by the end of his 1974 season. But Miller is not an especially ideal comparable to Spieth. Most obvious, he had won only one major through 1974; Spieth had three as of the end of 2017. More serious is the problem of looking at a single, potentially idiosyncratic, comparable. Miller, eventually done in by putting problems, concluded his career with a +36.80 rating. Nobody associates Spieth with putting problems.

Analysis of the Strokes Gained data portrays Spieth as a player without a chink. Since 2013 he has averaged 1.61 Strokes Gained on the field, topping at 2.15 in 2015 and measuring 1.88 in 2017. Those gains came from every area of the course: he acquired 22 percent of his advantage of the tee, 30 percent approaching the green, 19 percent around the green, and 28 percent on the green. Five seasons’ worth of data in four Strokes Gained categories produces twenty data points. In the case of Spieth, all twenty of those data points are positive, none is higher than 0.91, but only one is lower than 0.15. If one aspect of Spieth’s game goes bad in a given week, he can fall back on a lot of other reliable elements.

Spieth to Date

| Tournament | Finish | Score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2014 Masters |

T-2 |

283 |

–1.83 |

|

2014 U.S. Open |

T-17 |

284 |

–0.67 |

|

2015 Masters |

1st |

270 |

–2.79 |

|

2015 U.S. Open |

1st |

275 |

–2.03 |

|

2015 British Open |

T-4 |

274 |

–2.19 |

|

2nd |

271 |

–2.21 |

|

|

2016 Masters |

T-2 |

286 |

–1.63 |

|

2016 PGA |

T-13 |

274 |

–0.91 |

|

2017 Masters |

T-11 |

287 |

–0.70 |

|

2017 British Open |

1st |

268 |

–3.24 |

Note: Average Z score:–1.82. Effective stroke average: 69.29.

Spieth’s Career Record (2013–Present)

- Masters: 4 starts, 1 win (2015), –6.96

- U.S. Open: 5 starts, 1 win (2015), +0.55

- British Open: 5 starts, 1 win (2017), –5.53

- PGA: 5 starts, 0 wins, +2.67

- Total (19 starts): –9.28

Worth a Few Lines . . .

Justin Thomas: His victory in the 2017 PGA Championship and his carrying home of the FedEx Cup capped Thomas’s only second full season on the major circuit and constituted far and away his best showing to that date. His peak and career ratings as of the end of 2017 are identical: +0.42. That is a substantially less auspicious start than the PGA victory might suggest. To pick an obvious comparison, ten majors into his essentially parallel career, Jordan Spieth already had two major titles, and his peak and career scores had turned negative, which is good. Spieth’s next ten majors included a third title and four top fives; if Thomas approximates that, he’ll be fine. But that begs a question: Is Justin Thomas as good as Jordan Spieth? Despite the FedEx title, at this early stage in his career, the data are not (yet?) making that case. The average of Thomas’s Strokes Gained seasonal scores is 0.97; Spieth’s average for his first three seasons was 1.53. Thomas is, thus far anyway, displaying mediocrities Spieth has not shown, among them modest averages of 0.14 and 0.05 in Strokes Gained around and on the green. To date, Spieth is superior in all four Strokes Gained aspects. Thomas does have one thing going for him. His 2017 season constituted a dramatic uptick from his first two seasons, his overall Strokes Gained rising from 0.97 and 0.31 in 2015 and 2016 to 1.62 in 2017. If that trend proves more influential than the three-year average, Thomas may indeed challenge or surpass Spieth long term.

Dustin Johnson: Johnson won the 2016 U.S. Open and might have used that as a springboard to the dominance many have predicted for him. Instead, 2017 essentially became a waste season, its most memorable moment being a fall down some stairs prior to the Masters. In his five major starts since that victory at Oakmont, Johnson has missed two cuts and failed to finish higher than ninth . . . which he did once. Offsetting that, Johnson had by many standards a very nice 2017, finishing third in the FedEx Cup standings, winning three tournaments—among them two World Golf Championships—and leading the overall Strokes Gained list at 2.20. So he was to some extent a victim of this book’s reliance on criteria with a long history—the majors—as a basis for its ratings. In a sense, that makes Johnson king of the 2017 nonmajors.

Hideki Matsuyama: Only twenty-five at the conclusion of the 2017 season, Matsuyama has three top-five finishes among his most recent five major appearances, so a major victory in 2018 would surprise nobody. He was one of only five players on the men’s tour—the others were Matt Kuchar, Brooks Koepka, Rickie Fowler, and Paul Casey—to notch negative standard deviation ratings in all four 2017 majors. Since playing full-time on tour in 2014, Matsuyama has averaged 1.23 Strokes Gained, about 63 percent of that generated by his superiority approaching the green and another 37 percent off the tee. His problems have been with the putter, where he has on average given back 0.15 of a stroke per round. As long as he dominates off the tee and approaching the green—the two areas that most routinely correlate with stroke average—he can excel . . . but it would be nice to sink a putt now and then.

Rickie Fowler: Were Fowler to staple together back-to-back solid seasons, his relatively modest –1.28 peak rating Z score might be half a standard deviation better. Remember 2014, when Fowler finished among the top five in all four majors? He followed that with no top tens, only two top twenty-fives, and three missed cuts in his next nine major showings. Fowler hits age thirty in 2018, so he still has time to satisfy his legion of fans, of which this writer is one. At the same time, the 2017 major victories of Spieth, Koepka, and Thomas—all two or more years younger than Fowler—demonstrate how quickly the biological meter is running. Fowler presents a balanced game, gaining 1.00 strokes per round on the field, with roughly one-third of that coming off the tee, a second third approaching the green, and one-quarter of a stroke on the green. His relative weakness is in pitching and chipping.

Brooks Koepka: The 2017 season, highlighted, obviously, by his U.S. Open win, was by far Koepka’s best to date. Were he to replicate it, his –1.21 peak rating as of the end of 2017 would improve to –1.42 by the end of 2018, and to –1.57 by the end of 2019. That’s not all-time elite status, but it would stand behind only Spieth, McIlroy, and Day among his contemporaries. In 2017 Koepka’s Strokes Gained was about 0.90, ironically—considering his U.S. Open victory—his worst season-long performance to date. His advantages are predominately off the tee and on the greens, averaging a pickup of about 0.46 and 0.48 strokes in those areas.

Lexi Thompson: It takes a score of –1.95 to rank among the twenty-five best golfers of all time for peak performance. Thompson is one of only a handful of current players with a legitimate chance to reach that level. She ended the 2017 season at –1.65. A dominant 2018 featuring a couple of major victories and contending positions in the others—unlikely but imaginable—might make up the difference.

So Yeon Ryu: She is five years Thompson’s senior, but from a statistical standpoint they are a superb match. Ryu has two major titles to Thompson’s one, and Ryu’s –1.75 peak rating as of the end of the 2017 season is exactly one tick better than Thompson’s. Ryu’s career rating as of the end of 2017 is –24.07, giving her a decided edge over Thompson (–13.47) and Spieth (–9.28) in the race to crack that top twenty-five, where Lloyd Mangrum (–34.49) presently holds the twenty-fifth position. Ryu has gained furiously on Mangrum since 2016, adding 10.98 points to her career rating with three other top fives and five other top tens in addition to her 2017 ANA victory. If she maintains that pace, she’ll put Mangrum—along with Babe Zaharias, Kathy Whitworth and Pat Bradley—behind her by the start of the 2020 season.