Glossary

career value: See the appendix for formula.

correlative skills: These are skills related to golf for which sufficient data exist to facilitate correlations with scoring. More than 280 such correlative skills are presently maintained by the PGA Tour alone. But because many are duplicative or ancillary, this book primarily focuses on the skills defined below.

clubhead speed: Speed on which the club impacts the ball (mph) on par-four and par-five tee shots where a radar measurement was taken.

driving accuracy: The percentage of time a tee shot comes to rest in the fairway (regardless of club).

driving distance: The average number of yards per measured drive. Drives are measured on two holes per round. Care is taken to select two holes that face in opposite directions to counteract the effect of wind. Drives are measured to the point at which they come to rest regardless of whether they are in the fairway.

greens in regulation: The percentage of time a player was able to hit the green in regulation (greens hit in regulation/holes played.) A green is considered hit in regulation if any part of the ball is touching the putting surface after the GIR stroke has been taken. (The GIR stroke is determined by subtracting two from par.)

proximity: The average distance to the hole (in feet) after the player’s approach shot. The approach-shot distance must be determined by a laser and must not originate from or around the green. The shot must also end on or around the green or in the hole. “Around the green” indicates the ball is within thirty yards of the edge of the green.

putts: The average number of putts per round played.

scrambling: The percentage of time a player misses the green in regulation but still makes par or better.

peak value: See the appendix for formula.

regression analysis: A mathematical tool for measuring the strength of the relationship between any two sets of numbers—for example, putts per round and strokes per round. Regression analysis thus becomes a means of answering the extent to which ability in any golf-related skill influences one’s eventual score. The normal scale runs from a minimum of 0.0 to a maximum of 1.0, with 0.0 indicating no relationship and 1.0 indicating an extreme relationship. In situations where one number in the set might be expected to increase as the other declines—for instance, the relationship between driving distance and score—the correlation is expressed negatively, with 0.0 gain indicating no correlation and –1.0 indicating an extreme correlation.

The formula for calculating regression analysis for any set of numbers is as follows:

- 1. Find what is referred to as the dependent variable—in golf it might be driving distance, fairway accuracy, greens in regulation, or various others—for each player who has played a sufficient minimum number of holes to qualify.

- 2. Find what is referred to as the independent variable—for our purposes generally the score—for each player who has played a sufficient minimum number of holes to qualify.

- 3. For each qualified player, multiply the dependent variable by the average number for all players.

- 4. For each qualified player, multiply the independent variable by the average number for all players.

- 5. For each qualified player, multiply the result of step 3 by the result of step 4.

- 6. For each qualified player, calculate the square of the result of step 3.

- 7. For each qualified player, calculate the result of step 4.

- 8. Calculate the sums of the results for all qualified players of steps 5, 6, and 7.

- 9. Calculate the sum of the sums of step 6 multiplied by the sum of the sums of step 7.

- 10. Find the square root of the result of step 9.

- 11. Divide the sum of step 5 by the result of step 10.

standard deviation: A measure of any number relative to a “normal” set of numbers. In other words, it’s a gauge of exceptionality. The bell curve is the classic illustration of a “normal” distribution of data. If golfers produce scores in a “normal distribution” pattern, then there’s really no reason one can’t apply standard deviation to the assessment of that data. But if they don’t, one will have to find a new tool or abandon the project.

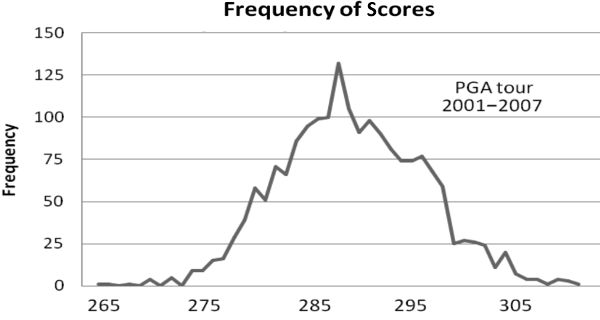

A sample of scores should suffice to test the premise. Between 2001 and 2007, more than thirty-three hundred four-round scores were recorded in major tournaments on the men’s and women’s tours. Relative to par, those scores ranged from a low of nineteen under to a high of thirty over. Our graph of the frequency of the occurrence of each score over that seven-year period may not be precise, because tournaments are played on different courses with different pars, and since this calculation is dealing with raw par figures, the data will not self-adjust to those differences. But allowing for some tolerance, if the graph looks like a bell curve, rock on. Following is the graph.

That may not be the most perfectly proportioned bell ever, but it’s certainly recognizable, and the raw-score variations are reasonably attributable to the differences that relate to varying pars.

One can run the same test for various eras of the game, and for the most part the pattern will hold. There are breakdowns, especially when reaching back into the game’s early eras. Those are roughly the pre-1970s for women and the pre-1920s for men. “Imperfect bell” breakdowns won’t invalidate the conclusions, but they may render them more marginal. That’s an official acknowledgment for the record to take the ratings of men from before 1920 and women from before 1970 as good-faith estimates but not precise calculations.

As a general proposition, one standard deviation movement away from the average in either direction will account for approximately 68 percent of all the results in a normal sample. Two standard deviations away from the mean accounts for roughly 95 percent of the data. Of course, only half of that movement will occur on the low end; the other half will be extraordinarily high. The bell has two sides, after all. A result three standard deviations outside the norm occurs only about 1 percent of the time, and again those 1 percent are split between the high and low ends. Throughout major tournament history, only about forty golfers—male and female—scored three standard deviations or better below the field average for the tournament in question. In major professional golf competition, results extending more than four standard deviations from the mean are exceedingly rare; there have been only three in the history of men’s and women’s major golf tournaments.

Simply put, the formula for calculating standard deviation is the average of the squared differences from the mean. Here is the more complex step-by-step formula:

- 1. Calculate the average for all numbers in the field.

- 2. Subtract each number from the average.

- 3. For each number, square the result of step 2.

- 4. Calculate the average of the squared differences. The result is the measure of one standard deviation from the field average.

Z score: Z score is a means of expressing exceptionality. It represents the number of standard deviations a given data point lies from the average. To calculate the Z score of any player in a golf tournament, begin by calculating the four-round field average and the standard deviation. Subtract the player’s four-round score from the four-round field average, and divide the result by the standard deviation. For scores that are below the field average—which is to say better—the Z score is negative. In most large data sets, 99 percent of values have a Z score between –3.00 and 3.00, meaning they lie within three standard deviations above or below the field average.